The Impact of Work Connectivity Behavior on Employee Time Theft: The Role of Revenge Motive and Leader–Member Exchange

Abstract

1. Introduction

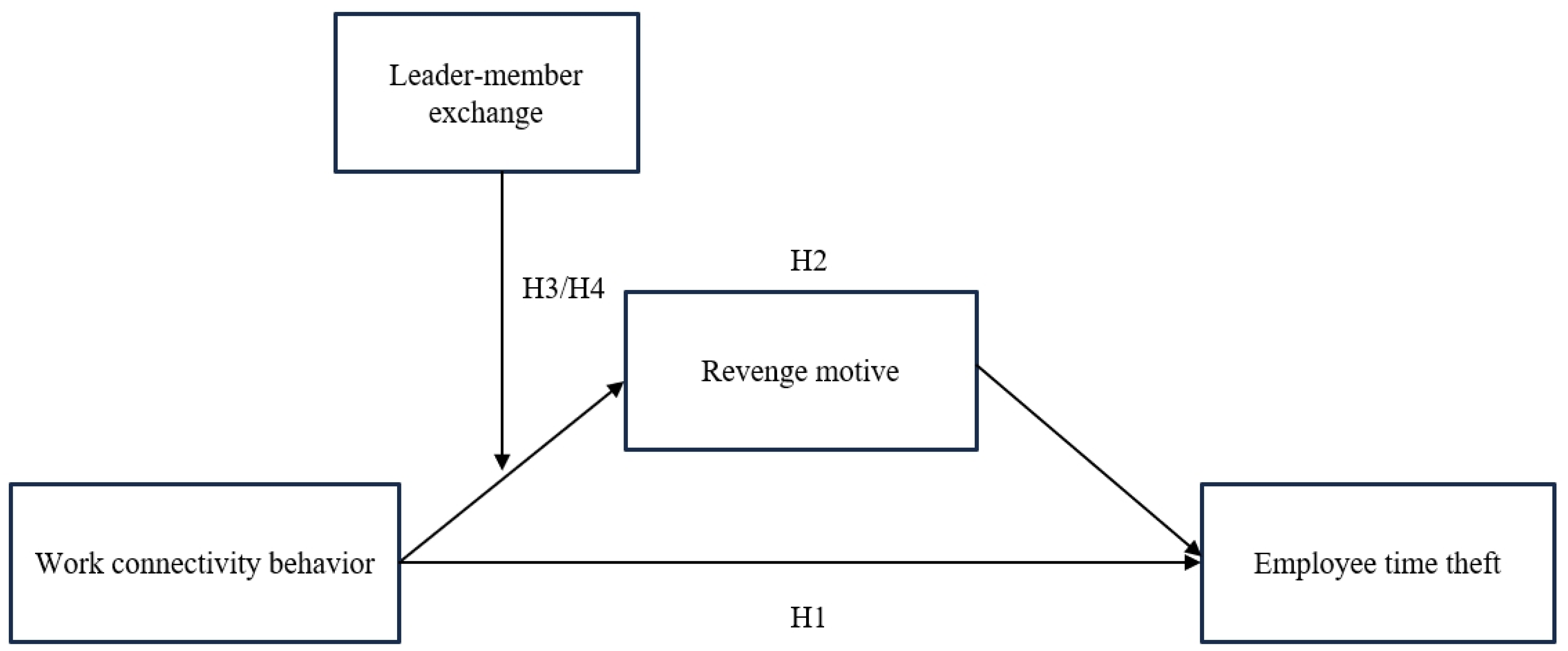

2. Literature Review, Hypotheses, and Conceptual Model

2.1. WCB

2.2. WCB and Employee Time Theft

2.3. The Mediating Role of Revenge Motive

2.4. The Moderating Role of LMX

3. Methods

3.1. Respondents and Procedures

3.2. Measurements

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Issues

4.2. Validity Test

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WCB | Work connectivity behavior |

| LMX | Leader–member exchange |

References

- Arlinghaus, A., & Nachreiner, F. (2013). When work calls—Associations between being contacted outside of regular working hours for work-related matters and health. Chronobiology International, 30(9), 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, L. J., Whiteside, D. B., & Aquino, K. (2014). To avenge or not to avenge? Exploring the interactive effects of moral identity and the negative reciprocity norm. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(1), 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, S. T. S., Grimstad, A., Škerlavaj, M., & Černe, M. (2017). Social and economic leader–member exchange and employee creative behavior: The role of employee willingness to take risks and emotional carrying capacity. European Management Journal, 35(5), 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. M. (2017). Exchange and power in social life. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidenthal, A. P., Liu, D., Bai, Y., & Mao, Y. (2020). The dark side of creativity: Coworker envy and ostracism as a response to employee creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 161, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Expanding the role of the interpreter to include multiple facets of intercultural communication. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 4(2), 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M. E., Martin, L. E., & Buckley, M. R. (2013). Time theft in organizations: The development of the time banditry questionnaire. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 21(3), 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchler, N., Ter Hoeven, C. L., & Van Zoonen, W. (2020). Understanding constant connectivity to work: How and for whom is constant connectivity related to employee well-being? Information and Organization, 30(3), 100302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazotte, F., Heloisa Lemos, A., & Villadsen, K. (2014). Corporate smart phones: Professionals’ conscious engagement in escalating work connectivity. New Technology, Work and Employment, 29(1), 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S. C. H., & Mak, W. (2012). Benevolent leadership and follower performance: The mediating role of leader–member exchange (LMX). Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(2), 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Wang, L., & Bao, J. (2022). Why does leader aggressive humor lead to bystander workplace withdrawal behavior?—Based on the dual path perspective of cognition-affection. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 925029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K., Cao, X., Guo, L., & Xia, Q. (2022). Work connectivity behavior after-hours and job satisfaction: Examining the moderating effects of psychological entitlement and perceived organizational support. Personnel Review, 51(9), 2277–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W., Kim, S. L., & Yun, S. (2019). A social exchange perspective of abusive supervision and knowledge sharing: Investigating the moderating effects of psychological contract fulfillment and self-enhancement motive. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(3), 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F., Zhang, J., Pellegrini, M. M., Wang, C., & Liu, Y. (2024). Staying connected beyond the clock: A talent management perspective of after-hours work connectivity and proactive behaviours in the digital age. Management Decision, 62(10), 3132–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogliser, C. C., & Brigham, K. H. (2004). The intersection of leadership and entrepreneurship: Mutual lessons to be learned. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 771–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmers, J., Vahle-Hinz, T., Bamberg, E., Friedrich, N., & Keller, M. (2016). Extended work availability and its relation with start-of-day mood and cortisol. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(1), 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M., Zhang, T., Li, Y., & Ren, Z. (2022). The effect of work connectivity behavior after-hours on employee psychological distress: The role of leader workaholism and work-to-family conflict. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 722679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., Lynch, P., Aselage, J., & Rohdieck, S. (2004). Who takes the most revenge? Individual differences in negative reciprocity norm endorsement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(6), 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faldetta, G. (2021). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance: The role of negative reciprocity. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 29(4), 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C., Dong, T., & Wang, J. (2024). Exploring the impact of after-hours work connectivity on employee performance: Insights from a job crafting perspective. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glomb, T. M., & Liao, H. (2003). Interpersonal aggression in work groups: Social influence, reciprocal, and individual effects. Academy of Management Journal, 46(4), 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M., Mehta, N. K. K., Agarwal, U. A., & Jawahar, I. M. (2025). The mediating role of psychological capital in the relationship between LMX and cyberloafing. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 46(1), 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis (4th ed.): With readings. Prentice-Hall, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Harold, C. M., Hu, B., & Koopman, J. (2022). Employee time theft: Conceptualization, measure development, and validation. Personnel Psychology, 75(2), 347–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R. (2003). Network time and the new knowledge Epoch. Time & Society, 12(2–3), 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H., Li, D., Zhou, Y., & Zhang, P. (2023). The spillover effect of work connectivity behaviors on employees’ family: Based on the perspective of work-home resource model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1067645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D. A., Morgeson, F. P., & Gerras, S. J. (2003). Climate as a moderator of the relationship between leader-member exchange and content specific citizenship: Safety climate as an exemplar. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G. C. (1974). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. Revue Française de Sociologie, 3(4), 450–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B., Harold, C. M., & Kim, D. (2023). Stealing time on the company’s dime: Examining the indirect effect of laissez-faire leadership on employee time theft. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(2), 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Kuang, T., & Lu, Y. (2024). The effect of work connectivity behavior after-hours on emotional exhaustion: The role of psychological detachment and work-family segmentation preference. Sage Open, 14(3), 21582440241281417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, T.-K., Chi, N.-W., & Lu, W.-L. (2009). Exploring the relationships between perceived coworker loafing and counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating role of a revenge motive. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24(3), 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Lang, K. R. (2005). Managing the paradoxes of mobile technology. Information Systems Management, 22(4), 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J. M., Opland, R. A., & Ryan, A. M. (2010). Psychological contracts and counterproductive work behaviors: Employee responses to transactional and relational breach. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(4), 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. A. (2004). Counterproductive work behavior toward supervisors & organizations: Injustice, revenge, & context. Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, 2004(1), A1–A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman-Scarborough, C. (2006). Time use and the impact of technology: Examining workspaces in the home. Time & Society, 15(1), 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R., & Tyler, T. (1996). Beyond distrust: “Getting even” and the need for revenge. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundro, T. G., Belinda, C. D., Affinito, S. J., & Christian, M. S. (2023). Performance pressure amplifies the effect of evening detachment on next-morning shame: Downstream consequences for workday cheating behavior. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(8), 1356–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L. W., & Xu, A. J. (2019). Power imbalance and employee silence: The role of abusive leadership, power distance orientation, and perceived organisational politics. Applied Psychology, 68(3), 513–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Shi, G., & Zheng, X. (2025). Differential effects of proactive and reactive work connectivity behavior after-hours on well-being at work: A boundary theory perspective. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C., Li, Z., Huang, L., & Todo, Y. (2024). Just seems to be working hard? Exploring how careerist orientation influences time theft behavior. Current Psychology, 43(31), 26064–26079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H., Joshi, A., & Chuang, A. (2004). Sticking out like a sore thumb: Employee dissimilarity and deviance at work*. Personnel Psychology, 57(4), 969–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., Aggarwal, A., Singh, V., & Gopal, R. (2024). Leader–member exchange and service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: A mediation-moderation model of employee envy and psychological empowerment among hotel frontline employees. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Bai, Q., Yuan, Y., Li, B., Liu, P., Liu, D., Guo, M., & Zhao, L. (2024). Impact of work connectivity behavior after-hours on employees’ unethical pro-family behavior. Current Psychology, 43(13), 11785–11803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhao, H., & Liu, L. (2023). The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on work connectivity behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 831862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, B., Xiao, J., Zhou, Y., Men, C., Li, F., & Chen, H. (2024). Serving as an ethical signal: Understanding how and when socially responsible human resource management inhibits time theft. Journal of Business Ethics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytinen, K., & Yoo, Y. (2002). Research commentary: The next wave of nomadic computing. Information Systems Research, 13(4), 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, A., & Kashif, M. (2019). Being abused, dealt unfairly, and ethically conflicting? Quitting occupation in the lap of silence. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 12(1), 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L. E., Brock, M. E., Buckley, M. R., & Ketchen, D. J. (2010). Time banditry: Examining the purloining of time in organizations. Human Resource Management Review, 20(1), 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLarty, B. D., Muldoon, J., Quade, M., & King, R. A. (2021). Your boss is the problem and solution: How supervisor-induced hindrance stressors and LMX influence employee job neglect and subsequent performance. Journal of Business Research, 130, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, J. H., & Baron, R. A. (1998). Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence concerning specific forms, potential causes, and preferred targets. Journal of Management, 24(3), 391–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson-Buchanan, J. B., & Boswell, W. R. (2006). Blurring boundaries: Correlates of integration and segmentation between work and nonwork. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y., Fritz, C., & Jex, S. M. (2011). Relationships between work-home segmentation and psychological detachment from work: The role of communication technology use at home. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(4), 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, L. M., & Spector, P. E. (2005). Job stress, incivility, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): The moderating role of negative affectivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(7), 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M. F. (2003). Book Reviews. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(1), 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasulova, D., & Tanova, C. (2025). The constant ping: Examining the effects of after-hours work connectivity on employee turnover intention. Acta Psychologica, 254, 104789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinke, K., & Ohly, S. (2021). Double-edged effects of work-related technology use after hours on employee well-being and recovery: The role of appraisal and its determinants. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift Für Personalforschung, 35(2), 224–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. L., & Greenberg, J. (1998). Employees behaving badly: Dimensions, determinants and dilemmas in the study of workplace deviance. Available online: http://www.mendeley.com/research/employees-behaving-badly-dimensions-determinants-dilemmas-study-workplace-deviance/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Schaffer, B. S., & Riordan, C. M. (2003). A review of cross-cultural methodologies for organizational research: A best-practices approach. Organizational Research Methods, 6(2), 169–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, N., Cortina, J. M., Ingerick, M. J., & Wiechmann, D. (2003). Personnel selection and employee performance. In Handbook of Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/0471264385.wei1205 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Senarathne Tennakoon, K. L. U., Da Silveira, G. J. C., & Taras, D. G. (2013). Drivers of context-specific ICT use across work and nonwork domains: A boundary theory perspective. Information and Organization, 23(2), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.-T., & Lin, C.-C. T. (2014). From good friends to good soldiers: A psychological contract perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31(1), 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. (2012). Psychological detachment from work during leisure time: The benefits of mentally disengaging from work. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(2), 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: The stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework: The stressor-detachment model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), S72–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S., & Niessen, C. (2020). To detach or not to detach? Two experimental studies on the affective consequences of detaching from work during non-work time. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 560156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S., Venz, L., & Casper, A. (2017). Advances in recovery research: What have we learned? What should be done next? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, I. K., Bernhard, F., Hameister, N., & Miller, K. (2023). Lessons from family firms: The use of flexible work arrangements and its consequences. Review of Managerial Science, 17(1), 175–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M., Tu, Q., Ragu-Nathan, B. S., & Ragu-Nathan, T. S. (2007). The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(1), 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Hoeven, C. L., Van Zoonen, W., & Fonner, K. L. (2016). The practical paradox of technology: The influence of communication technology use on employee burnout and engagement. Communication Monographs, 83(2), 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Jaarsveld, D. D., Walker, D. D., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2010). The role of job demands and emotional exhaustion in the relationship between customer and employee incivility. Journal of Management, 36(6), 1486–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D. T., Barnes, C. M., Lim, V. K. G., & Ferris, D. L. (2012). Lost sleep and cyberloafing: Evidence from the laboratory and a daylight saving time quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(5), 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Zhang, Z., & Shi, W. (2023). Relationship between daily work connectivity behavior after hours and work–leisure conflict: Role of psychological detachment and segmentation preference. PsyCh Journal, 12(2), 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Li, Z., Bu, C., & Zhu, W. (2023). Work connectivity behavior after-hours spills over to cyberloafing: The roles of motivation and workaholism. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 38(8), 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Wang, Q., & Wang, D. (2024). Reducing employees’ time theft through leader’s developmental feedback: The serial multiple mediating effects of perceived insider status and work passion. Behavioral Sciences, 14(4), 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. S. (1995). Chinese social orientation: An integrative analysis. Chinese Societies and Mental Health, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., Yan, R., Li, X., Meng, Y., & Xie, G. (2023). Different results from varied angles: The positive impact of work connectivity behavior after-hours on work engagement. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y., Yan, R., & Meng, Y. (2022). Can’t disconnect even after-hours: How work connectivity behavior after-hours affects employees’ thriving at work and family. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 865776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L., Su, Y., Jolly, P. M., & Bao, S. (2025). Leader aggressive humor and hospitality employees’ time theft: The roles of ego depletion and self-compassion. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 127, 104121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P., Hu, L., & Li, F. S. (2025). My coworkers tell me they are paid more than me! The I-EDM model perspective on time theft behaviors. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 129, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F., Gao, Y., & Chen, X. (2024). Freedom or bondage? The double-edged sword effect of work connectivity behavior after-hours on employee occupational mental health. Chinese Management Studies, 18(1), 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Type | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 147 | 44.5 |

| Female | 183 | 55.5 | |

| Age(year) | Less than 25 | 52 | 15.8 |

| 26–30 | 119 | 36.1 | |

| 31–35 | 117 | 35.5 | |

| 36–45 | 32 | 9.7 | |

| More than 45 | 10 | 3 | |

| Education | High school or below | 8 | 2.4 |

| Associate degree | 32 | 9.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 247 | 74.8 | |

| Master’s degree or above | 43 | 13 | |

| Years of work experience | Less than 1 | 25 | 7.6 |

| 1–3 | 80 | 24.2 | |

| 3–5 | 86 | 26.1 | |

| 5–10 | 120 | 36.4 | |

| More than 10 | 19 | 5.8 | |

| Job position level | Ordinary staff | 167 | 50.6 |

| Frontline management | 88 | 26.7 | |

| Middle management | 57 | 17.3 | |

| Top management | 18 | 5.5 | |

| Sleep quality | Poor | 15 | 4.5 |

| Average | 85 | 25.8 | |

| Good | 230 | 69.7 | |

| Role integration preference | Dislike | 206 | 62.4 |

| Like | 124 | 37.6 |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model: | 421.38 | 183 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.06 |

| Three-factor model 1: | 821.70 | 186 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.10 |

| Combining WCB and LMX | |||||

| Three-factor model 2: | 1335.39 | 186 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.14 |

| Combining revenge motive and employee time theft | |||||

| Two-factor model: | 1418.30 | 188 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.14 |

| Combining WCB, LMX and revenge motive | |||||

| One-factor model: | 3774.95 | 189 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.23 |

| Combining all variables | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Age | −0.04 | - | |||||||||

| 3. Education | −0.05 | −0.09 | - | ||||||||

| 4. Years of work experience | −0.04 | 0.67 ** | 0.04 | - | |||||||

| 5. Job position level | −0.11 | 0.35 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.35 ** | - | ||||||

| 6. Sleep quality | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.16 ** | 0.01 | - | |||||

| 7. Role integration preference | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.12 * | 0.17 ** | 0.14 * | 0.20 ** | - | ||||

| 8. WCB | 0.21 ** | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.06 | 0.13 * | −0.07 | 0.20 ** | (0.73) | |||

| 9. LMX | 0.14 ** | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.15 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.54 ** | (0.75) | ||

| 10. Revenge motive | 0.09 | −0.23 ** | −0.05 | −0.35 ** | −0.13 * | −0.29 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.05 | (0.85) | |

| 11. Employee time theft | −0.01 | −0.22 ** | −0.06 | −0.38 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.26 ** | 0.11 * | −0.23 ** | 0.54 ** | (0.89) |

| Mean | 0.55 | 2.48 | 2.98 | 3.08 | 1.78 | 2.65 | 0.38 | 4.16 | 3.86 | 3.18 | 2.43 |

| SD | 0.50 | 0.97 | 0.57 | 10.07 | 0.92 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 1.08 | 0.78 |

| Revenge Motive | Employee Time Theft | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | |

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.09 |

| Age | −0.12 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Education | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| Years of work experience | −0.22 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.15 * | −0.20 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.13 | −0.13 ** |

| Job position level | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.05 |

| Sleep quality | −0.44 ** | −0.41 ** | −0.40 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.26 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.13 | −0.12 |

| Role integration preference | −0.26 * | −0.35 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.31* | −0.27 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.19 | −0.21 * |

| Independent variable | ||||||||

| WCB | 0.31 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.08 | 0.15 * | 0.06 | |||

| Mediator | ||||||||

| Revenge motive | 0.31 ** | 0.30 ** | ||||||

| Moderator | ||||||||

| LMX | −0.03 | −0.11 | ||||||

| Interaction | ||||||||

| WCB × LMX | −0.24 ** | |||||||

| R2 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| ΔR2 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| F | 11.23 ** | 12.04 ** | 10.68 ** | 11.16 ** | 12.46 ** | 11.91 ** | 22.55 ** | 20.17 ** |

| Effect (SE) | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low LMX (−1 SD) | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.0246 | 0.1314 |

| High LMX (+1 SD) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.1288 | 0.0518 |

| Difference | −0.11 (0.03) | −0.1826 | −0.0490 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Huang, J.; Zhu, J. The Impact of Work Connectivity Behavior on Employee Time Theft: The Role of Revenge Motive and Leader–Member Exchange. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 738. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060738

Wang C, Huang J, Zhu J. The Impact of Work Connectivity Behavior on Employee Time Theft: The Role of Revenge Motive and Leader–Member Exchange. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):738. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060738

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Cuiying, Jianfeng Huang, and Jianping Zhu. 2025. "The Impact of Work Connectivity Behavior on Employee Time Theft: The Role of Revenge Motive and Leader–Member Exchange" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 738. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060738

APA StyleWang, C., Huang, J., & Zhu, J. (2025). The Impact of Work Connectivity Behavior on Employee Time Theft: The Role of Revenge Motive and Leader–Member Exchange. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 738. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060738