Does Disinformation Toward Women Politicians Reflect Gender Stereotypes? Exploring the Role of Leaders’ Political Orientations

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Gender Gap and Sexist Stereotypes in Political Media Coverage

1.2. Information Disorders and Their Stereotypes in the Political Field

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview and Objectives

2.2. Collecting Procedure and Coding

- Inclusion criteria: the content falls under the definition of information disorder and is about Italian female politicians.

- Exclusion criteria: the content does not meet the definition of information disorder or involves an Italian men politician, a non-political Italian woman, or non-Italian men/female politicians.

2.2.1. Type of Information Disorder

- Satire and Parody: satiric or parodic content that people could consider real news.

- False Connection: contents in which headlines, visuals or captions do not support the article’s information (like clickbait headlines).

- Misleading Content: contents in which accurate information is framed to inaccurately represent an issue or an individual (e.g., “SCHLEIN RIDES ON THE GAY PRIDE FLOAT: IT’S THE BIBBIANO’S PARTY—VIDEO”).

- False Context: accurate contents that circulated out of their original context, misleading the reader.

- Imposter Content: contents that improperly used organizations’ logos or journalists’ bylines.

- Manipulated Content: genuine contents that are manipulated to deceive (e.g., two genuine images spliced together to manipulate the reader or convey a certain message).

- Fabricated Content: false contents meant to propagate incorrect information (e.g., “She wants to take money from the poor and workers but earns €25,000 a month. Meloni cuts YOUR income!”).

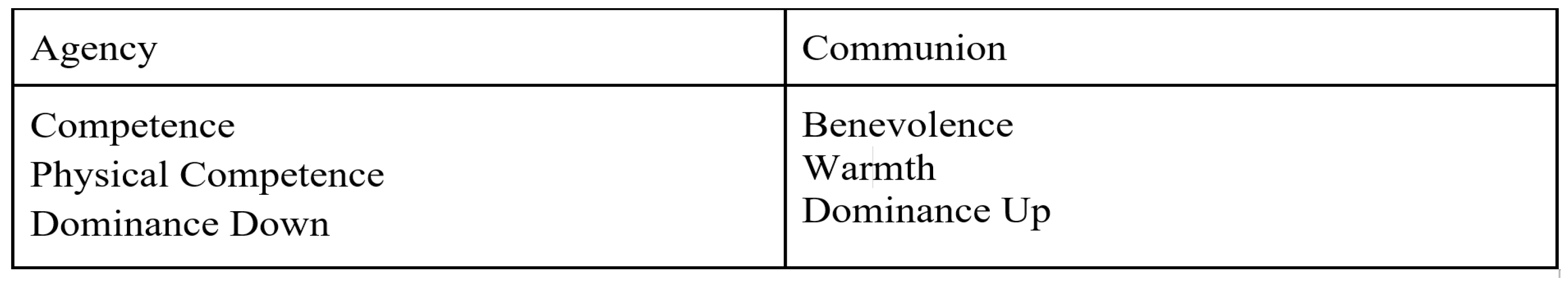

2.2.2. Stereotype Content

- Benevolence: the target is portrayed as dishonest, immoral, illegal, unethical (e.g., “Elly Schlein’s PD stands with thieves: what this photo reveals”. Note: “PD” stands for “Democratic Party”.).

- Warmth: the target is portrayed as emotionally distant, callous, heartless.

- Competence: the target is portrayed as stupid, incompetent.

- Physical Competence: the focus is on the target’s appearance and how it deviates from esthetic standards.

- Dominance Up: the target is portrayed as overly dominant, arrogant, overbearing (e.g., “The school will be open until the final teacher is alive.” Citation attributed to politician Lucia Azzolina).

- Dominance Down: the target is portrayed as nondominant, irrelevant, useless (e.g., “European elections, the PD hides Schlein’s name from the party symbol. They are ashamed of her.”).

- No stereotyping: the content has no stereotyping purposes.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Qualitative Lexicon Analysis

“Meloni obeys her American masters: Salvini’s concerns about giving weapons to Kyiv”.

“Meloni butler: organizes a meeting between Biden and Zelenski during the G7 in Italy”.

“Cirinnà: ‘We will re-educate your children’”.

“She wants to take money from the poor and workers, and she earns €25,000 every month. Meloni cuts your income”.

“What if he was the one who brought love back into the Premier’s broken heart?”

“Schlein the lesbian rejoices”.

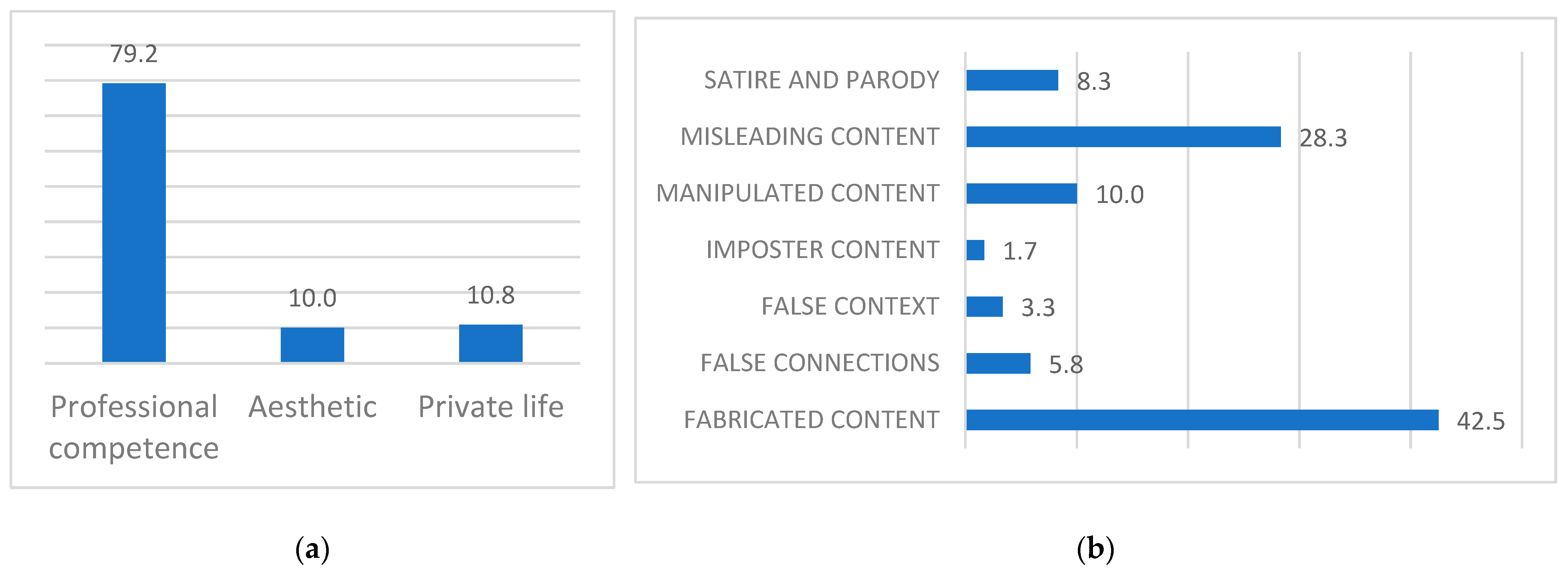

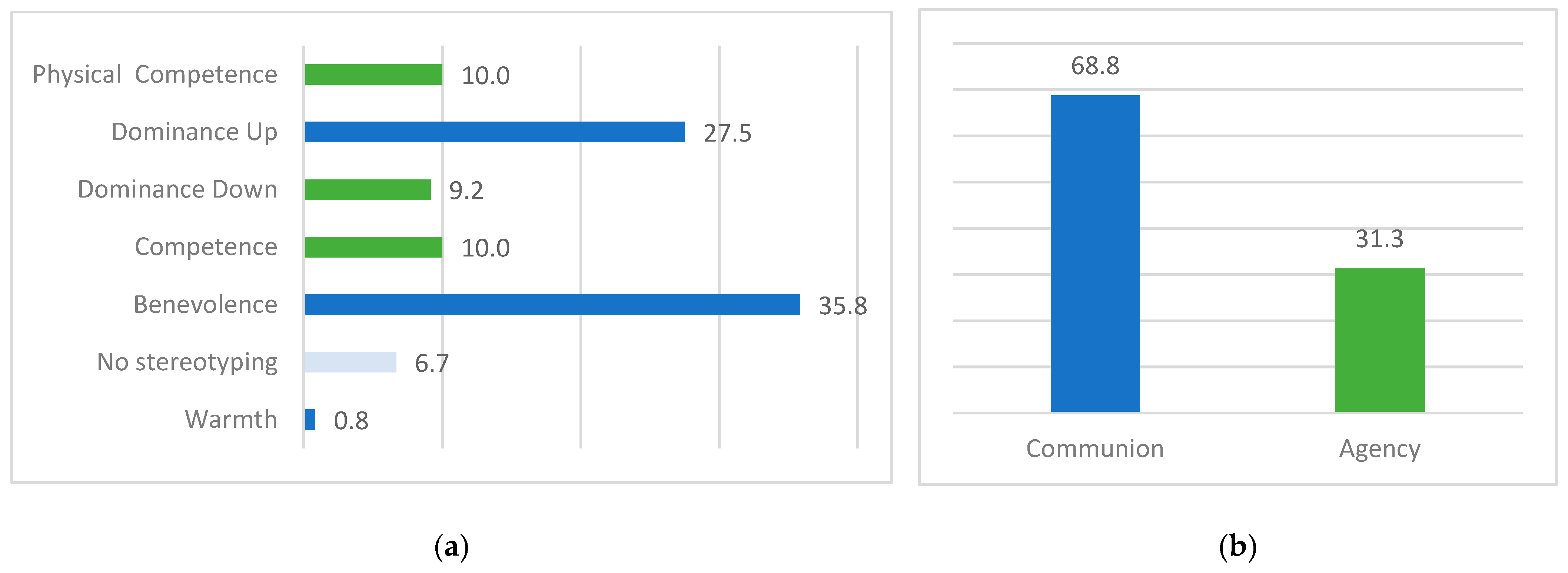

3.2. Corpus Descriptives

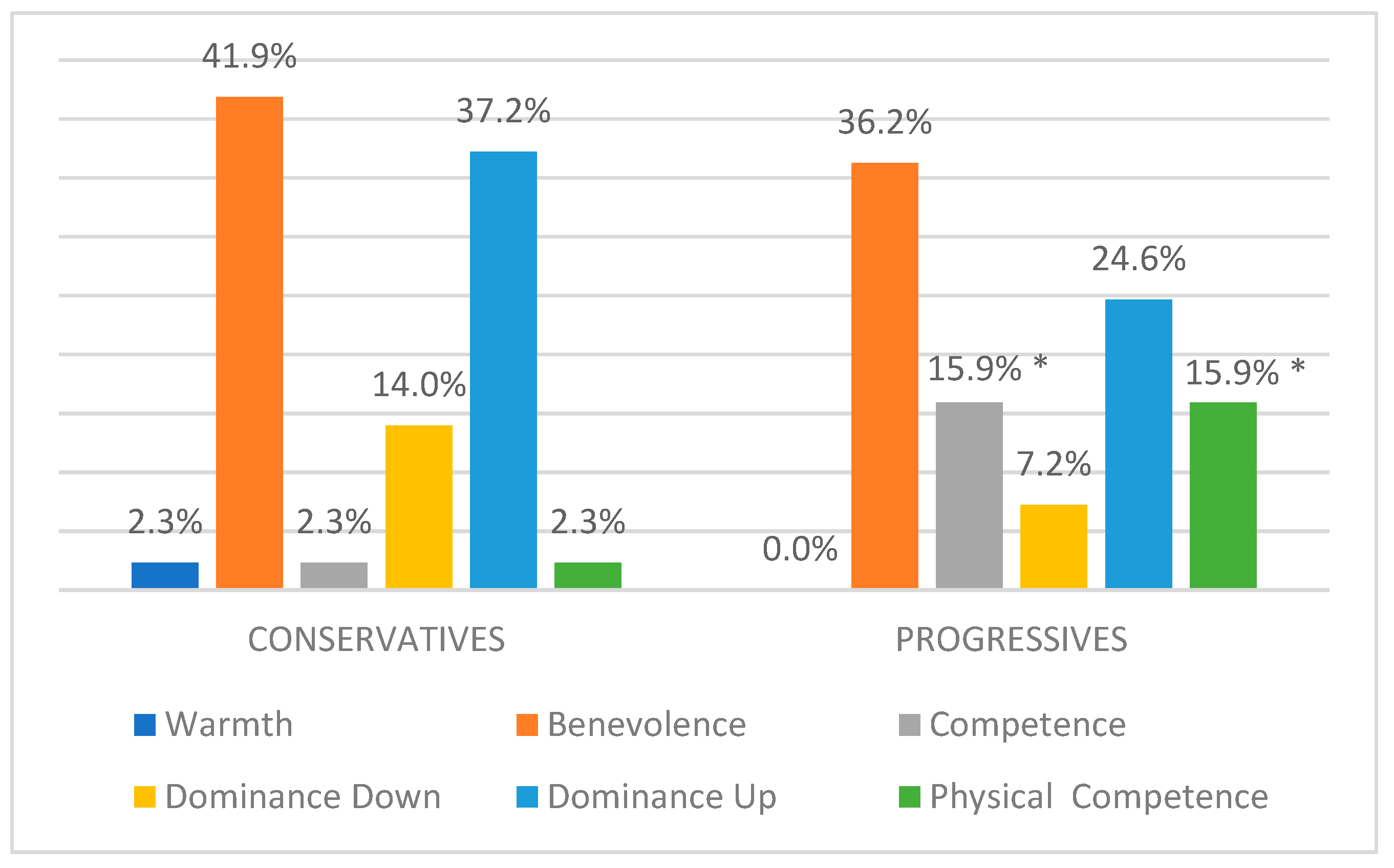

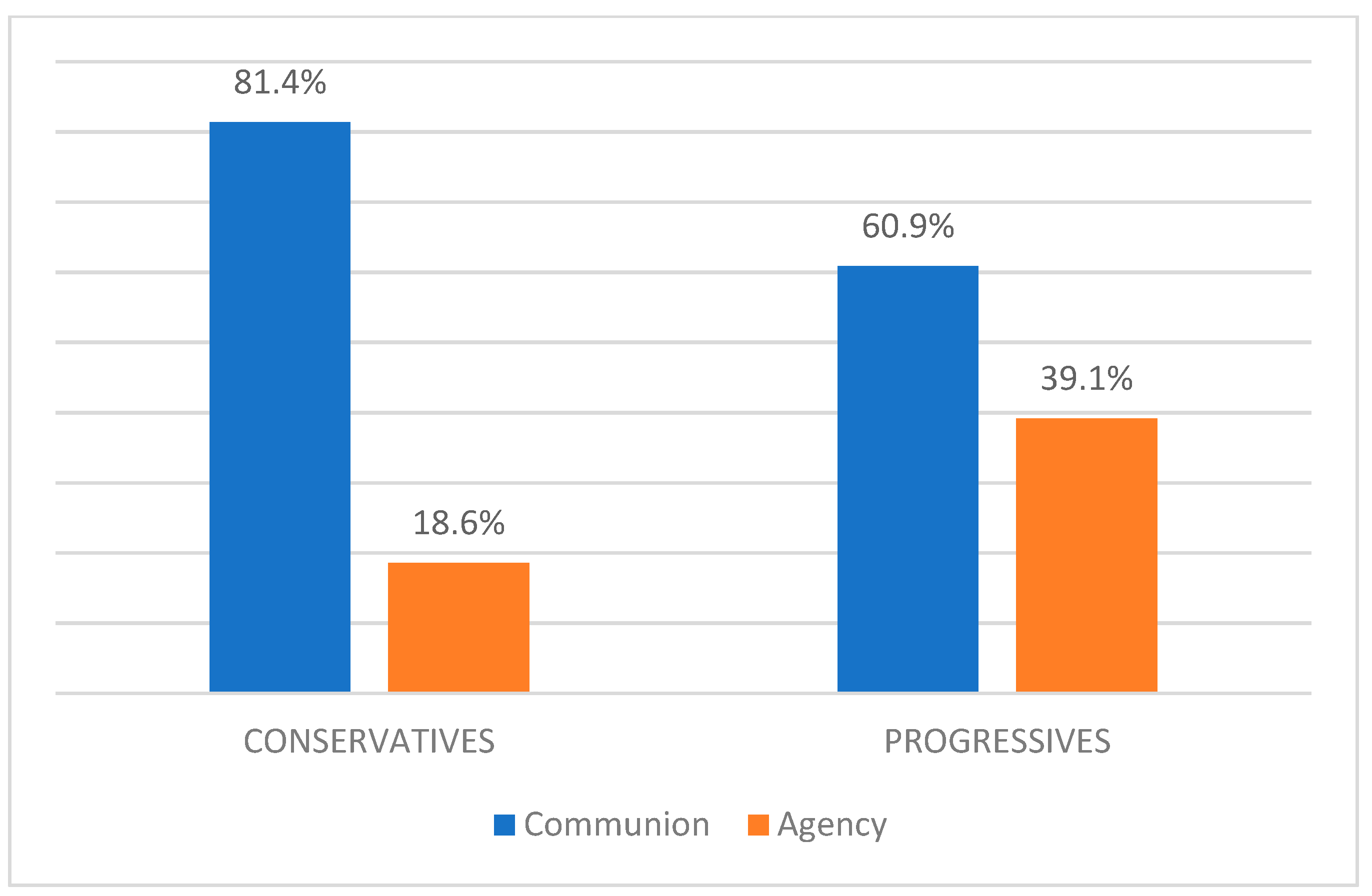

3.3. Political Orientation

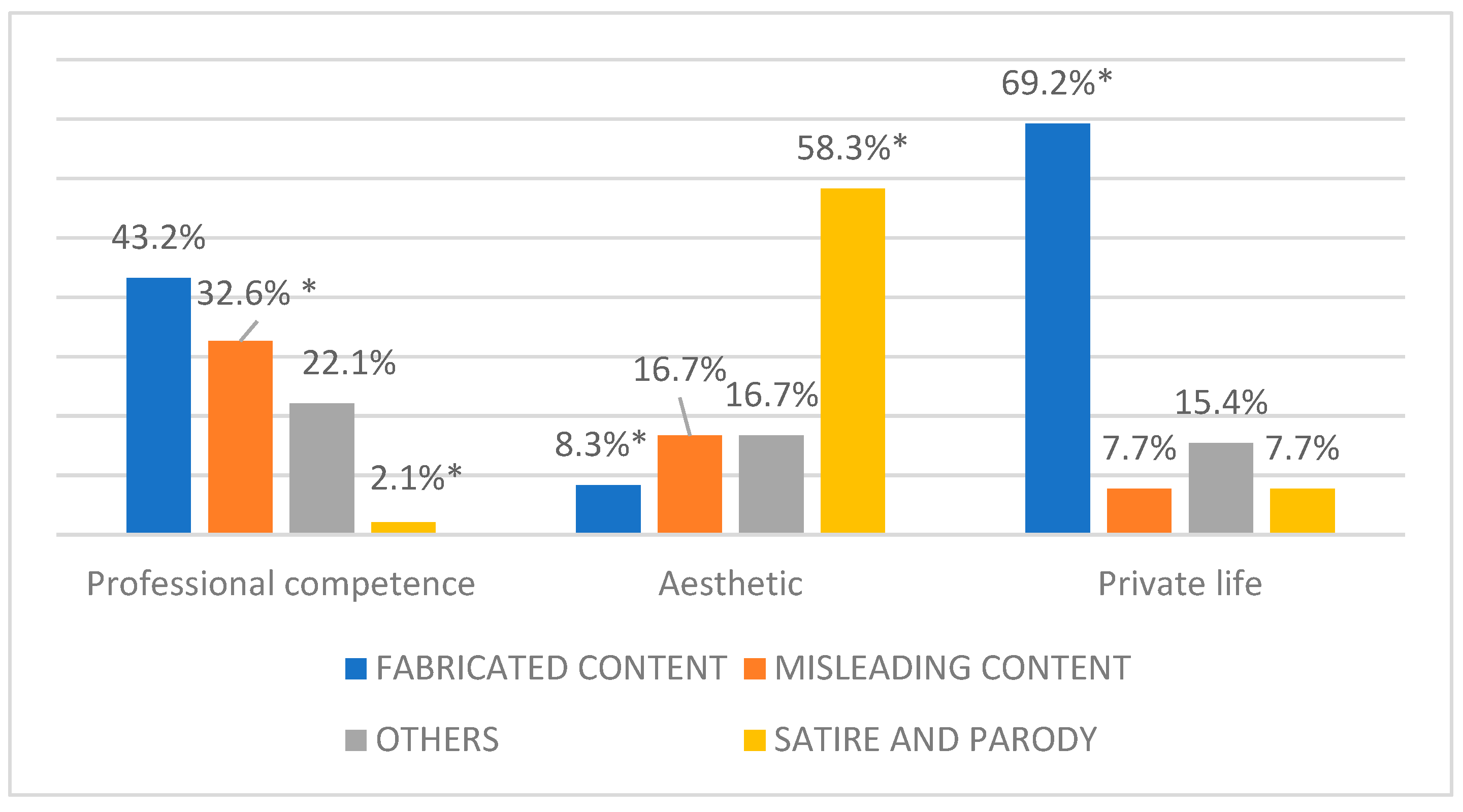

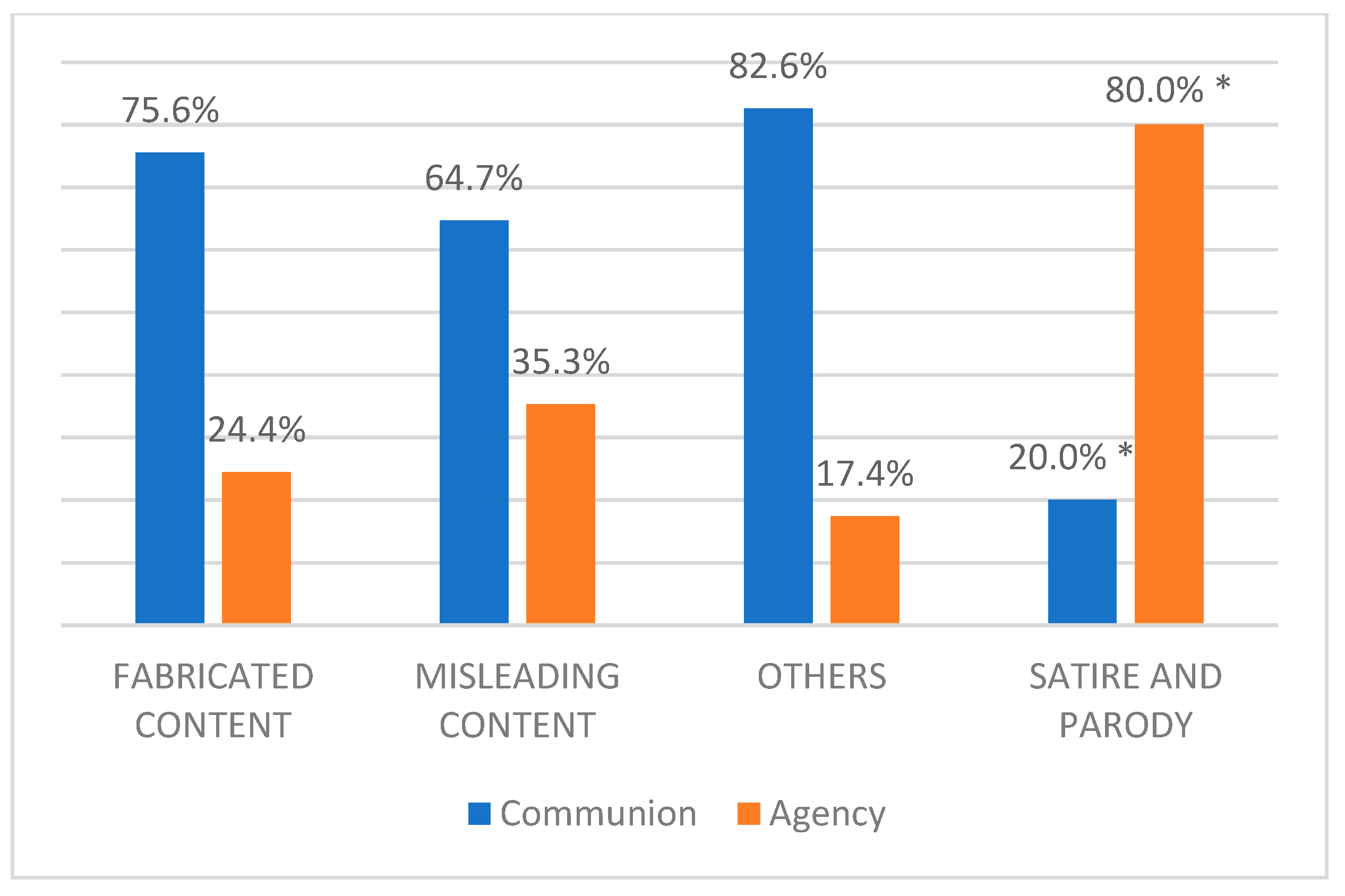

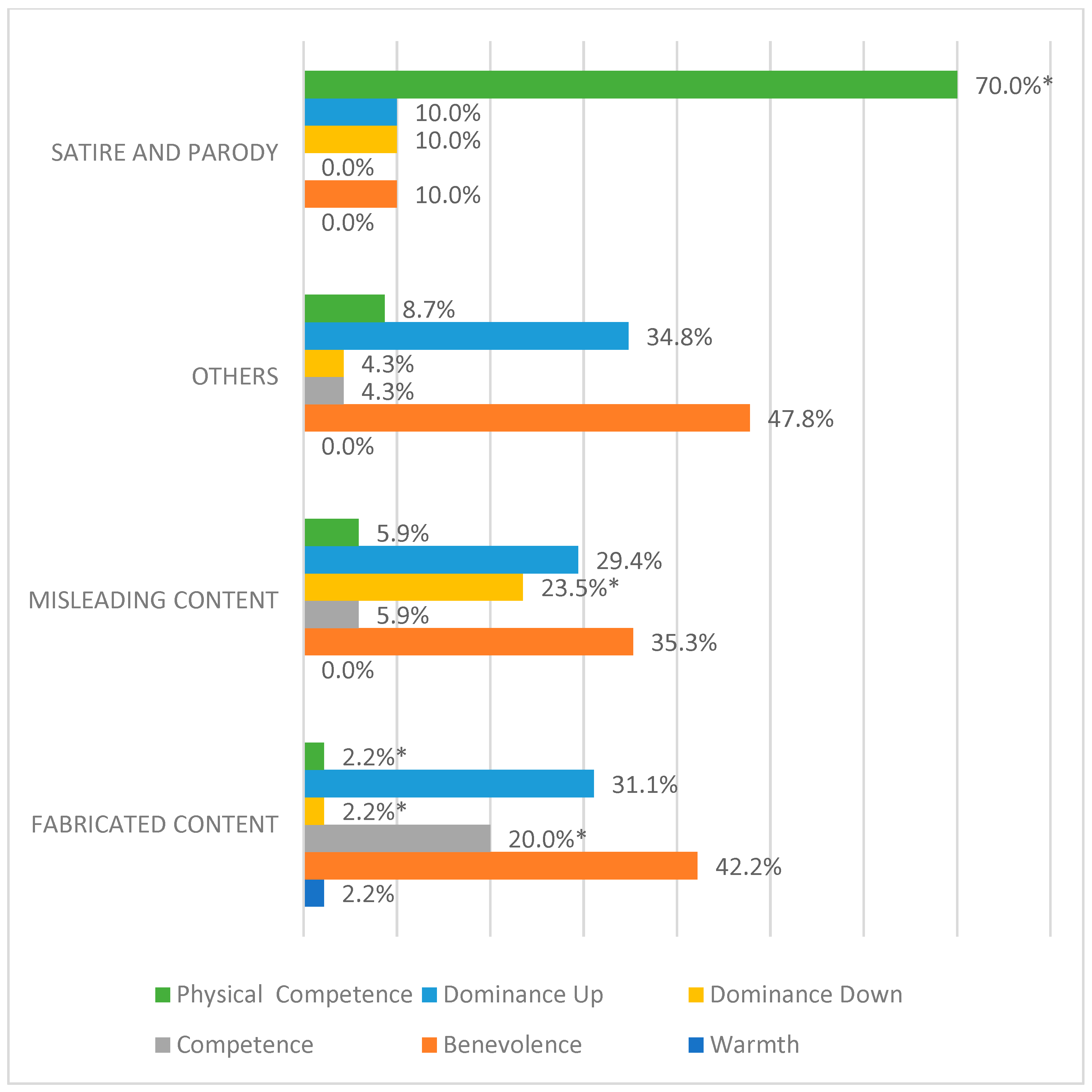

3.4. Information Disorders

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abele, A. E., Hauke, N., Peters, K., Louvet, E., Szymkow, A., & Duan, Y. (2016). Facets of the fundamental content dimensions: Agency with competence and assertiveness—Communion with warmth and morality. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2014). Chapter four—Communal and agentic content in social cognition: A Dual perspective model. In J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 50, pp. 195–255). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, A. (2019). Cultural evolution in the digital age. Oxford University Press. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=it&lr=&id=OVS_DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Acerbi,+Alberto.+2019.+Cultural+evolution+in+the+digital+age.+Oxford+University+Press.&ots=D3k_yS-5Jw&sig=yd7VN2fg7vVe5jxkFCn-zlypPaM (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, F. (2023). Media stereotypes, prejudice, and preference-based reinforcement: Toward the dynamic of self-reinforcing effects by integrating audience selectivity. Journal of Communication, 73(5), 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L. (2015). Sexist coverage of Liz Kendall and female politicians is insidious and demeaning. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/jul/20/sexist-coverage-liz-kendall-female-politicians-damage-voter-perceptions (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Bosco, C., Patti, V., Frenda, S., Cignarella, A. T., Paciello, M., & D’Errico, F. (2023). Detecting racial stereotypes: An Italian social media corpus where psychology meets NLP. Information Processing & Management, 60(1), 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpinella, C. M., & Johnson, K. L. (2013). Appearance-based politics: Sex-typed facial cues communicate political party affiliation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(1), 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/RECORD/1998-07091-021 (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Conroy, M., Oliver, S., Breckenridge-Jackson, I., & Heldman, C. (2015). From ferraro to palin: Sexism in coverage of vice presidential candidates in old and new media. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 3(4), 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, F. (2019). ‘Too humble and sad’: The effect of humility and emotional display when a politician talks about a moral issue. Social Science Information, 58(4), 660–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, F., Cicirelli, P. G., Corbelli, G., & Paciello, M. (2024). Rolling minds: A conversational media to promote intergroup contact by countering racial misinformation through socioanalytic processing in adolescence. Psychology of Popular Media. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2025-18155-001 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- D’Errico, F., Papapicco, C., & Delor, M. T. (2022). «Immigrants, hell on board»: Stereotypes and prejudice emerging from racial hoaxes through a psycho-linguistic analysis. Journal of Language & Discrimination, 6(2), 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, F., & Poggi, I. (2016). “The Bitter Laughter”. When parody is a moral and affective priming in political persuasion. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaway, J., Lawrence, R. G., Rose, M., & Weber, C. R. (2013). Traits versus issues: How female candidates shape coverage of senate and gubernatorial races. Political Research Quarterly, 66(3), 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellemers, N. (2018). Gender stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1), 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraldsson, A., & Wängnerud, L. (2019). The effect of media sexism on women’s political ambition: Evidence from a worldwide study. Feminist Media Studies, 19(4), 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehman, E., Carpinella, C. M., Johnson, K. L., Leitner, J. B., & Freeman, J. B. (2014). Early processing of gendered facial cues predicts the electoral success of female politicians. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(7), 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldman, C., Conroy, M., & Ackerman, A. R. (2018). Sex and gender in the 2016 presidential election. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=it&lr=&id=MkrEEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Heldman,+C.,+Conroy,+M.,+%26+Ackerman,+A.+R.+(2018).+Sex+and+gender+in+the+2016+Presidential+election.+Santa+Barbara,+CA:+Praeger&ots=fCmKwzWb7c&sig=yNjkN3doj7k4u1y4_STfzWc4zFs (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Herrero-Diz, P., Pérez-Escolar, M., & Sánchez, J. F. P. (2020). Desinformación de género: Análisis de los bulos de Maldito Feminismo. Revista ICONO 14. Revista Científica de Comunicación y Tecnologías Emergentes, 18(2), 188–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, R., & McGee, S. (2014). Teaching about propaganda: An examination of the historical roots of media literacy. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 6(2), 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, K. H. (1995). Beyond the double bind: Women and leadership. Oxford University Press. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=it&lr=&id=67DB9krBq2oC&oi=fnd&pg=PA3&dq=Jamieson,+K.+H.+1995.+Beyond+the+Double+Bind:+Women+and+Leadership.+Oxford:+Oxford+University+Press.&ots=D72Fo9kMTj&sig=jfWFF7LanbaUVeJ_8lSya4R3NEM (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Exceptions that prove the rule–Using a theory of motivated social cognition to account for ideological incongruities and political anomalies: Reply to Greenberg and Jonas (2003). Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2003-00782-005.html (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Sulloway, F. J., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2018). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. In The motivated mind (pp. 129–204). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(4), 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A. M., Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., & Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 616–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laustsen, L. (2017). Choosing the right candidate: Observational and experimental evidence that conservatives and liberals prefer powerful and warm candidate personalities, respectively. Political Behavior, 39(4), 883–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R. G. (2000). Game-framing the issues: Tracking the strategy frame in public policy news. Political Communication, 17(2), 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E. A., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingiardi, V., Carone, N., Semeraro, G., Musto, C., D’Amico, M., & Brena, S. (2020). Mapping Twitter hate speech towards social and sexual minorities: A lexicon-based approach to semantic content analysis. Behaviour & Information Technology, 39(7), 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, D. N., & Waldron, I. (1997). Attitudes toward cohabitation, family, and gender roles: Relationships to values and political ideology. Sociological Perspectives, 40(2), 199–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J., & Rauchfleisch, A. (2013). The Swiss “Tina fey effect”: The content of late-night political humor and the negative effects of political parody on the evaluation of politicians. Communication Quarterly, 61(5), 596–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neylan, J., Biddlestone, M., Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2023). How to “inoculate” against multimodal misinformation: A conceptual replication of Roozenbeek and van der Linden (2020). Scientific Reports, 13(1), 18273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmundsen, M., Bor, A., Vahlstrup, P. B., Bechmann, A., & Petersen, M. B. (2021). Partisan polarization is the primary psychological motivation behind political fake news sharing on Twitter. American Political Science Review, 115(3), 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciello, M., D’Errico, F., Saleri, G., & Lamponi, E. (2021). Online sexist meme and its effects on moral and emotional processes in social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 116, 106655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you. penguin UK. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=it&lr=&id=-FWO0puw3nYC&oi=fnd&pg=PT24&dq=Pariser,+E.+(2011).+The+filter+bubble:+What+the+Internet+is+hiding+from+you.+penguin+UK.&ots=g6JpHouRR_&sig=5Hpm8oGx9bqD65JZM847HZGWpQc (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Paul, C., & Matthews, M. (2016). The Russian «Firehose of Falsehood» propaganda model: Why it might work and options to counter it. RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2019). Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition, 188, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petla, V. (2023). Information disorders and civil unrest: An analysis of the July 2021 unrest in South Africa. Digital Policy Studies, 2(1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escolar, M., & Noguera-Vivo, J. M. (2021). How did we get here? The consequences of deceit in addressing political polarization. In Hate speech and polarization in participatory society. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, I., & D’Errico, F. (2018). Feeling offended: A blow to our image and our social relationships. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 308059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, I., D’Errico, F., & Vincze, L. (2011). Discrediting moves in political debate. In Proceedings of second international workshop on user models for motivational systems: The affective and the rational routes to persuasion (UMMS 2011) (Girona) (Vol. 740, pp. 84–99). CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Springer LNCS. [Google Scholar]

- Raquel, T., Dafne, C., & Maria, I.-C. (2024). #Feminazis on Instagram: Hate speech and misinformation, the ongoing discourse for enlarging the manosphere. KOME, 12(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G. (2024). Fake news: Vivere e sopravvivere in un mondo post-verità. Available online: https://www.torrossa.com/it/resources/an/5705296 (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Roets, A., & Van Hiel, A. (2009). The ideal politician: Impact of voters’ ideology. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(1), 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (1999). Feminized management and backlash toward agentic women: The hidden costs to women of a kinder, gentler image of middle managers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(5), 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M., Prot, S., Anderson, C. A., & Lemieux, A. F. (2017). Exposure to Muslims in Media and Support for Public Policies Harming Muslims. Communication Research, 44(6), 841–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoniccolo, F., Trombetta, T., Paradiso, M. N., & Rollè, L. (2023). Gender and media representations: A review of the literature on gender stereotypes, objectification and sexualization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharrer, E., & Warren, S. (2022). Adolescents’ modern media use and beliefs about masculine gender roles and norms. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 99(1), 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, N., Bains, A., Mushtaq, A., & Aleem, S. (2018). Analysing threads of sexism in new age humour: A content analysis of internet memes. Indian Journal of Social Research, 59(3), 355–367. [Google Scholar]

- Signorello, R., D’Errico, F., Poggi, I., & Demolin, D. (2012, September 3–5). How charisma is perceived from speech: A multidimensional approach. The 2012 International Conference on Privacy, Security, Risk and Trust and 2012 International Confernece on Social Computing (pp. 435–440), Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabile, B., Grant, A., Purohit, H., & Harris, K. (2019). Sex, lies, and stereotypes: Gendered implications of fake news for women in politics. Public Integrity, 21(5), 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, J. (2017). Adolescent girls’ stem identity formation and media images of stem professionals: Considering the influence of contextual cues. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 239856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C. R. (2001). Echo chambers: Bush v. Gore, impeachment, and beyond. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia, S., & Rollero, C. (2015). Gender stereotyping in newspaper advertisements: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46(8), 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, N. A., Wayne, C., & Oceno, M. (2018). Mobilizing sexism: The interaction of emotion and gender attitudes in the 2016 US presidential election. Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(S1), 799–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Pas, D. J., & Aaldering, L. (2020). Gender differences in political media coverage: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 70(1), 114–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Valkenburgh, S. P. (2021). Digesting the red pill: Masculinity and neoliberalism in the manosphere. Men and Masculinities, 24(1), 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpato, C. (2022). Psicosociologia del maschilismo. Gius Laterza & Figli Spa. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, C. (2018). The need for smarter definitions and practical, timely empirical research on information disorder. Digital Journalism, 6(8), 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking (Vol. 27). Council of Europe Strasbourg. Available online: http://tverezo.info/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/PREMS-162317-GBR-2018-Report-desinformation-A4-BAT.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Woodall, G. S., & Fridkin, K. L. (2007). 4. Shaping Women’s Chances: Stereotypes and the Media. In Rethinking madam president: Are we ready for a woman in the white house? (pp. 69–86) Lynne Rienner Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C. L., & Duong, H. (2021). COVID-19 fake news and attitudes toward Asian Americans. Journal of Media Research, 14(1), 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K. A. M., & Holland, J. (2014). Leadership and the media: Gendered framings of Julia Gillard’s ‘sexism and misogyny’ speech. Australian Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, F., & Kohring, M. (2020). Mistrust, disinforming news, and vote choice: A panel survey on the origins and consequences of believing disinformation in the 2017 German parliamentary election. Political Communication, 37(2), 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sportelli, C.; D’Errico, F. Does Disinformation Toward Women Politicians Reflect Gender Stereotypes? Exploring the Role of Leaders’ Political Orientations. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 695. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050695

Sportelli C, D’Errico F. Does Disinformation Toward Women Politicians Reflect Gender Stereotypes? Exploring the Role of Leaders’ Political Orientations. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):695. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050695

Chicago/Turabian StyleSportelli, Carmela, and Francesca D’Errico. 2025. "Does Disinformation Toward Women Politicians Reflect Gender Stereotypes? Exploring the Role of Leaders’ Political Orientations" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 695. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050695

APA StyleSportelli, C., & D’Errico, F. (2025). Does Disinformation Toward Women Politicians Reflect Gender Stereotypes? Exploring the Role of Leaders’ Political Orientations. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 695. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050695