4.1. Theoretical Contributions

First, this study explored the impact effects and functional logic of TSG responsible behaviors among short video app users. Through theoretical deduction, empirical investigation, and testing, a fundamental theoretical framework for TSG responsible behaviors among short video app users was established. Thus, the paper expanded the research on intangible cultural heritage responsible behaviors and provided a new perspective on this phenomenon.

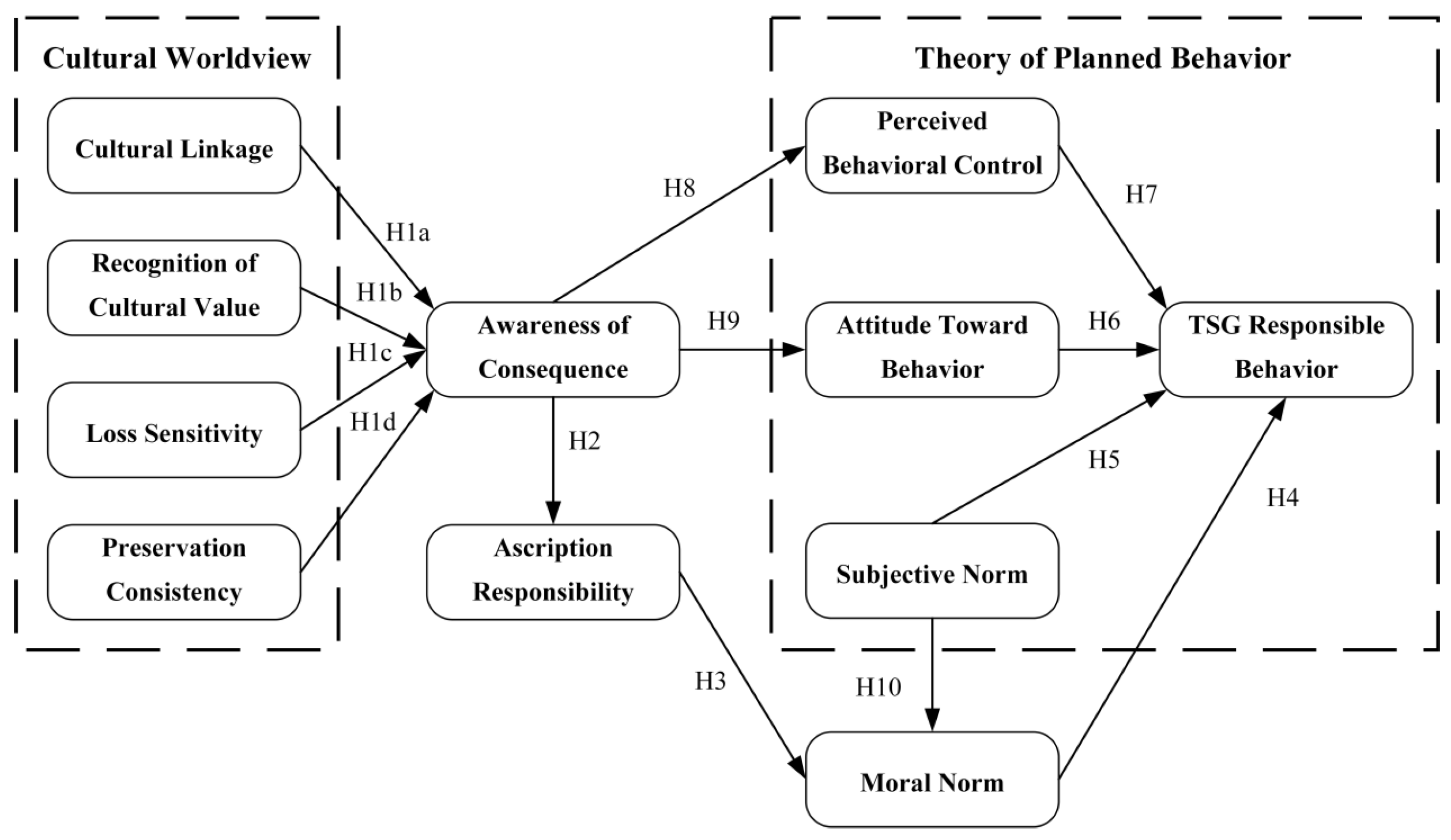

By employing an integrated VBN and TPB model, this study conducted an empirical investigation into the influencing mechanisms of TSG responsible behaviors among short video app users, further confirming the effectiveness of this integrated model in explaining prosocial behaviors (

Al Mamun et al., 2024). The integration of the VBN and TPB models represents a fusion of cultural values with behavioral intentions, as well as social influence with personal responsibility. Specifically, VBN provides the backdrop of individual values and cultural identity, while TPB reveals how individuals transform these cultural values into concrete protective behaviors. As a medium for cultural dissemination and responsibility activation (

Zhang, 2024), short videos enable audiences not only to understand the cultural values of TSG, but also effectively stimulate their sense of responsibility for protecting traditional culture (

L. Chen, 2023), thus motivating them to engage in corresponding protective behaviors. On the one hand, the concepts of “cultural value identity” and “responsibility attribution” in VBN explain why individuals develop a sense of responsibility to protect TSG after watching short videos. On the other hand, “subjective norms” in TPB further elucidate that when audiences perceive support and expectations from society or groups, they are more likely to engage in protective behaviors. Especially on short video platforms, social norms are often expressed through interactive behaviors, such as comments, likes, or shares, thereby reinforcing individual responsibility and behavioral intentions.

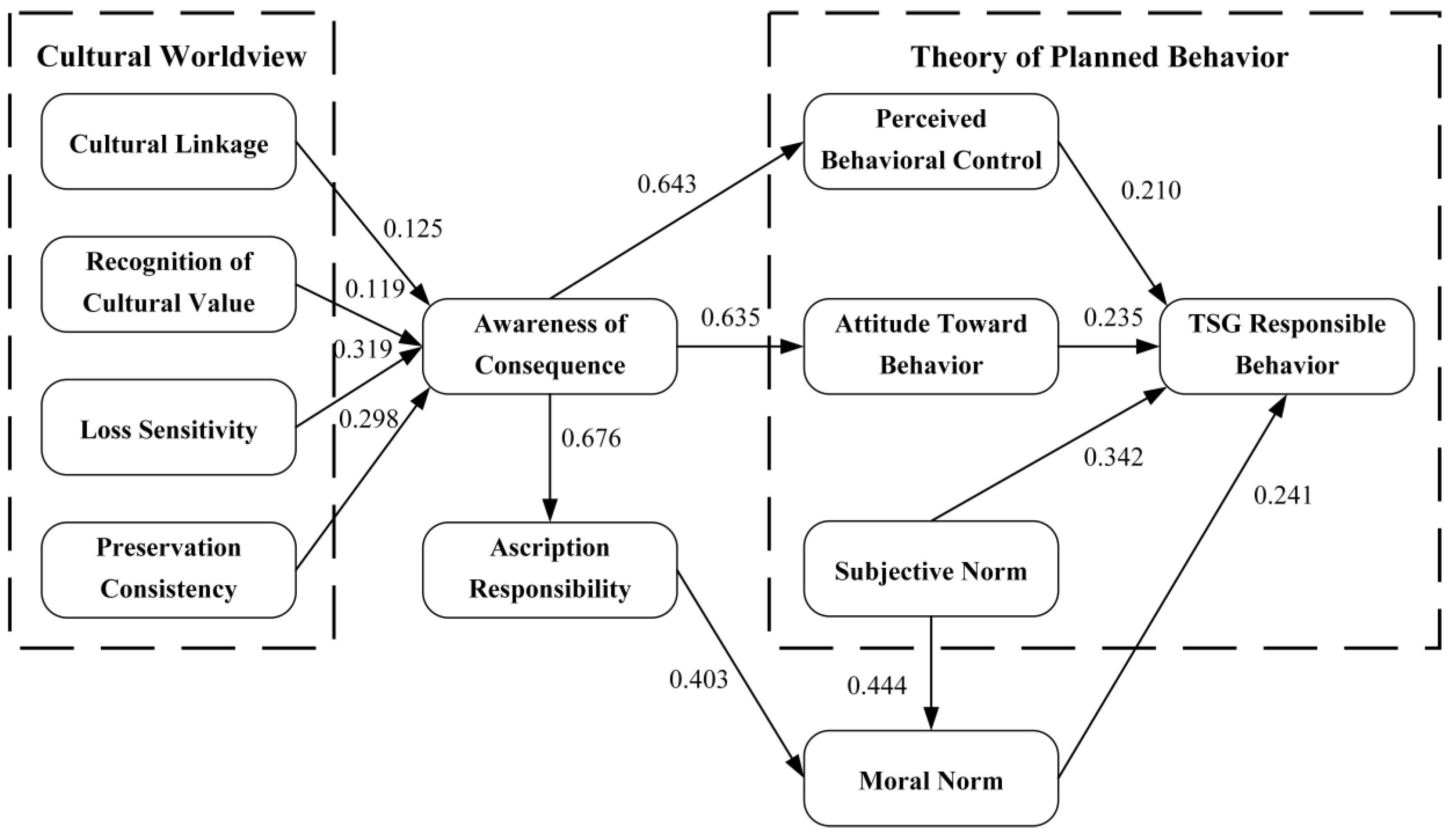

Second, this study provides a multifaceted theoretical understanding of the formation of TSG responsible behaviors among short video app users. First, it identifies four key influencing factors for TSG responsible behavior: moral norms, perceived behavioral control, attitude toward behavior, and subjective norms. Then, it recognizes the complex mediation mechanisms through which individuals’ attitudes toward culture profoundly affect their cognition of the potential consequences of an activity, their evaluation of specific behaviors, their judgment of self-capability in completing certain tasks, and their personal moral values, which, in turn, promote the emergence of TSG responsible behaviors.

Furthermore, this study clarifies six equivalent combinations of antecedent variables that contribute to the generation of TSG responsible behaviors among short video app users. Additionally, it reveals the complex interactions and asymmetrical effects of the antecedent conditions on TSG responsible behavior, meaning that the influence of antecedent variables on TSG responsible behaviors is neither independent nor equivalent. The emergence of TSG responsible behaviors involves the interaction of multiple antecedent conditions, demonstrating the complexity of causal relationships. This finding corresponds with current research on enhancing the protection and inheritance of TSG through new media technologies (

Gursoy et al., 2019) while providing empirical support for it.

Third, in deriving the universality of the integrated VBN and TPB model in the formation mechanism of TSG responsible behaviors, this study adopts a mixed research method, combining PLS-SEM with fsQCA to address the limitations of a single symmetric analysis (

Fiss, 2007). In particular, Study 1 tested the validity of the hypothesized model using PLS-SEM, aiming to clarify the impact effects and functional logic of different antecedent variables on TSG responsible behaviors as the outcome variable. Study 2 employed fsQCA to examine the configurational effects of antecedent variables, deepening the understanding of the antecedent occurrence patterns of TSG responsible behaviors among short video app users while also enhancing the recognition of the interaction between different antecedent variables. Thus, Study 2 contributes to the accurate identification of the contextual environment of variable influence effects and functional logic, providing valuable extensions to the integrated VBN and TPB model.

4.2. Managerial Implications

This study offers several practical implications. First, users who have watched TSG-related short videos often possess a more positive CW, higher awareness of consequence, and a stronger sense of responsibility. These values, beliefs, and norms increase their likelihood of engaging in TSG responsible behaviors. By analyzing user similarities and leveraging advanced algorithmic technologies to match shared interests, short video platforms are able to use collaborative filtering algorithms based on user profiles to push personalized content. Additionally, short video platforms skillfully integrate user preferences with big data from mobile social networks, relying on efficient algorithmic recommendation systems to achieve deep customization and wide dissemination of content. This mechanism, based on users’ interactive feedback and viewing behavior data, automatically elevates highly attractive video content to higher-level distribution channels, effectively promoting viral information dissemination and broad exposure to high-quality content. Thus, despite the differences in algorithm implementation across short video platforms in different regions, they all demonstrate significant effectiveness in enhancing TSG exposure and public attention. Therefore, countries should actively explore innovative approaches, fully leveraging mainstream short video platforms, such as TikTok, YouTube Shorts, and Instagram, to deeply integrate local TSG elements with short video media, thus creating new models for protection, display, transmission, and development (

Ramon & Rojas-Torrijos, 2022).

Furthermore, TSGs worldwide, such as cricket in the UK or flamenco dance in Spain, can fully utilize short video platforms for dissemination and protection. Specific strategies include systematically incorporating heritage protection responsibility concepts into short video content, enhancing creative design of relevant elements, and particularly emphasizing the sense of responsibility and ethical principles associated with TSG protection and transmission. Such an approach guides users in forming positive cultural attitudes and behavioral patterns. Additionally, deeply exploring the cultural connotations and values of TSGs is essential, using scenario simulations and problem warnings to raise public awareness of the urgency of TSG protection. Doing so can inspire the public’s intrinsic motivation to take positive protective measures. Furthermore, TSG inheritors should be encouraged to use short videos to document their daily training, competition moments, and the stories behind them, showcasing their unique skills and cultural heritage to larger audiences. By initiating challenges and topic activities centered around TSG transmission, users are encouraged to imitate, innovate, and share their own TSG experiences, fostering widespread user participation and topic discussion. By collaborating with educational institutions, cultural organizations, and tourism departments to launch combined online and offline experiences, such as virtual tours and workshops, TSG dissemination channels and audience bases can be further broadened, ultimately achieving the goal of cultivating national TSG responsible behaviors.

However, practical challenges must be addressed. First, the transparency of platform algorithms is a critical issue. Many short video platforms operate their recommendation algorithms as “black boxes”, making it difficult for users to understand how content is actually curated, specifically how TSG-related content is promoted. This lack of transparency could result in insufficient exposure for TSG content, which may be replaced by more entertainment-oriented content, thereby hindering the accurate transmission of cultural heritage.

Second, internal priority conflicts within platforms may arise. To pursue commercial interests, platforms tend to prioritize content that is popular and generates more engagement, while TSG content is often overlooked. This conflict between commercial interests and cultural protection limits the widespread dissemination of TSGs and requires a balanced approach to ensure that both types of content can coexist and thrive.

Finally, evolving regulatory environments also present challenges. Differences in cultural heritage protection laws across various countries and regions impose compliance pressures on short video platforms when promoting TSG globally. Furthermore, increasingly stringent data privacy regulations may limit platforms’ ability to use personal data for algorithmic personalization, thus affecting the effectiveness of content recommendation systems. In such a dynamic regulatory environment, platforms must be adaptable, adjusting their strategies to ensure the continuous dissemination of TSG content.

Notably, perceived behavioral control, moral norm, and subjective norm are also key factors that directly influence TSG responsible behaviors among short video app users. This insight opens up new avenues for promoting TSG responsible behaviors. From the perspective of perceived behavioral control, short video platforms should strive to create a low-threshold but high-reward creative and dissemination environment, thus reducing the difficulty and cost of user participation in TSG content creation through technological optimization and resource allocation. For example, developing specialized TSG content creation tools, providing templates, material libraries, and editing guidance ensure that users can easily get started. All of these effectively increase the quantity and quality of content, thereby enhancing users’ perceptions of their ability to positively influence TSG dissemination. On the level of moral norm, platforms can deeply explore the cultural value and ethical significance behind TSGs, thus leveraging the influence of social media by inviting celebrities, cultural scholars, and TSG inheritors to serve as “opinion leaders”, making positive statements to strengthen societal moral consensus on TSG protection. Finally, regarding subjective norms, platforms should encourage positive interactions and feedback mechanisms among users. These efforts may include setting up functions for likes, comments, and shares, enabling users to feel supported and recognized by the community and thus enhancing their subjective willingness to adhere to moral norm and participate in TSG protection. Nevertheless, challenges remain in ensuring that users’ engagement is not only genuine but sustained. Overcoming issues, such as user apathy and platform fatigue, requires continuous innovation in how TSG content is presented and incentivized.

Finally, the occurrence of TSG responsible behaviors is closely related to the variables in the theoretical model. However, the influence of these antecedent variables on TSG responsible behaviors must be realized through mediating mechanisms. Specifically, CW, awareness of consequence, and ascription of responsibility influence TSG responsible behaviors through mediating variables, including perceived behavioral control, attitude toward behavior, subjective norm, and moral norm. Therefore, to transform CW, awareness of consequence, and ascription of responsibility into actual TSG responsible behaviors, short video platforms and users should focus on the intermediary conditions for the transition of these three variables to TSG responsible behaviors. Through publicity, education, and information push mechanisms, these mediating factors should be effectively regulated to maximize the role of CW, awareness of consequence, and ascription of responsibility in the formation of heritage responsible behaviors. For example, users can be subtly influenced to develop a positive attitude toward behavior and enhance their moral norm recognition by using the push mechanism of short video platforms, regularly conveying the value significance of TSG protection to users, and emphasizing its positive impact on social development. In TSG short video creation, the cultural heritage and value connotations of TSG projects should be deeply explored, and users’ subjective norm levels should be enhanced through interaction. By sharing success stories and providing positive feedback, short video app users’ self-efficacy in engaging in TSG responsible behaviors can be strengthened, boosting their confidence in engaging in TSG responsible behaviors, enhancing their perceived behavioral control levels, and strengthening their TSG responsible behaviors. However, to ensure the sustainability of these efforts, careful consideration of regulatory and platform-specific challenges is needed. This is because regulatory environments may affect the ability of platforms to carry out these initiatives, and internal conflicts between platform goals (commercial versus cultural preservation) might hinder the implementation of certain strategies.