A Lost Opportunity to Reduce Future Risk Among Justice-Involved Young Adults Through HIV Testing and Counseling

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background/Rationale

1.2. Predictors of HIV Testing

1.3. Outcomes of HIV Testing

1.4. Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

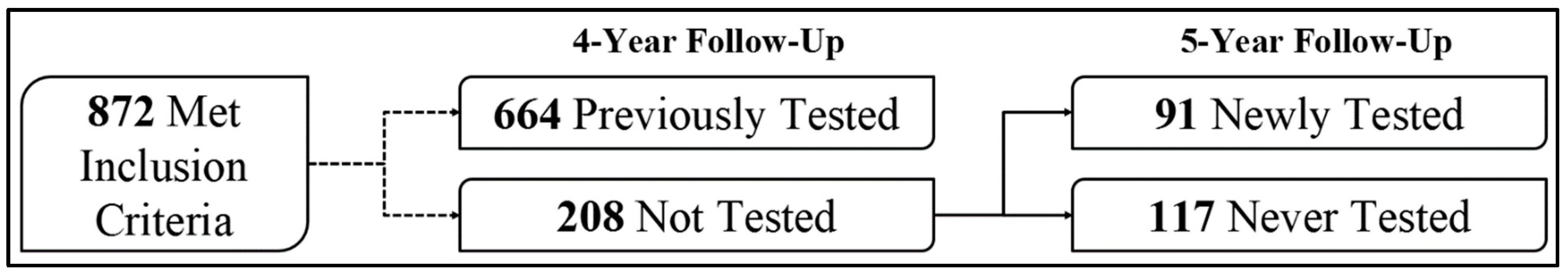

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Sampling and Sample Size

2.3. Design

2.3.1. Baseline Factors Associated with Future HIV Testing

2.3.2. Behavioral Outcomes After HIV Testing

2.4. Measures, Aim 1: Predictors of HIV Testing

2.4.1. Key Grouping Variable: HIV Testing

2.4.2. Individual Factors

2.4.3. Contextual Factors

2.4.4. Demographic Factors

2.5. Measures, Aim 2: Outcomes Associated with HIV Testing

2.5.1. Substance Use Frequency

2.5.2. Risky Sexual Behavior

2.5.3. Covariates

2.6. Statistical Analysis, Aim 1: Predictors of HIV Testing

2.7. Statistical Analysis, Aim 2: Outcomes Associated with HIV Testing

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Aim 1: Predictors of HIV Testing

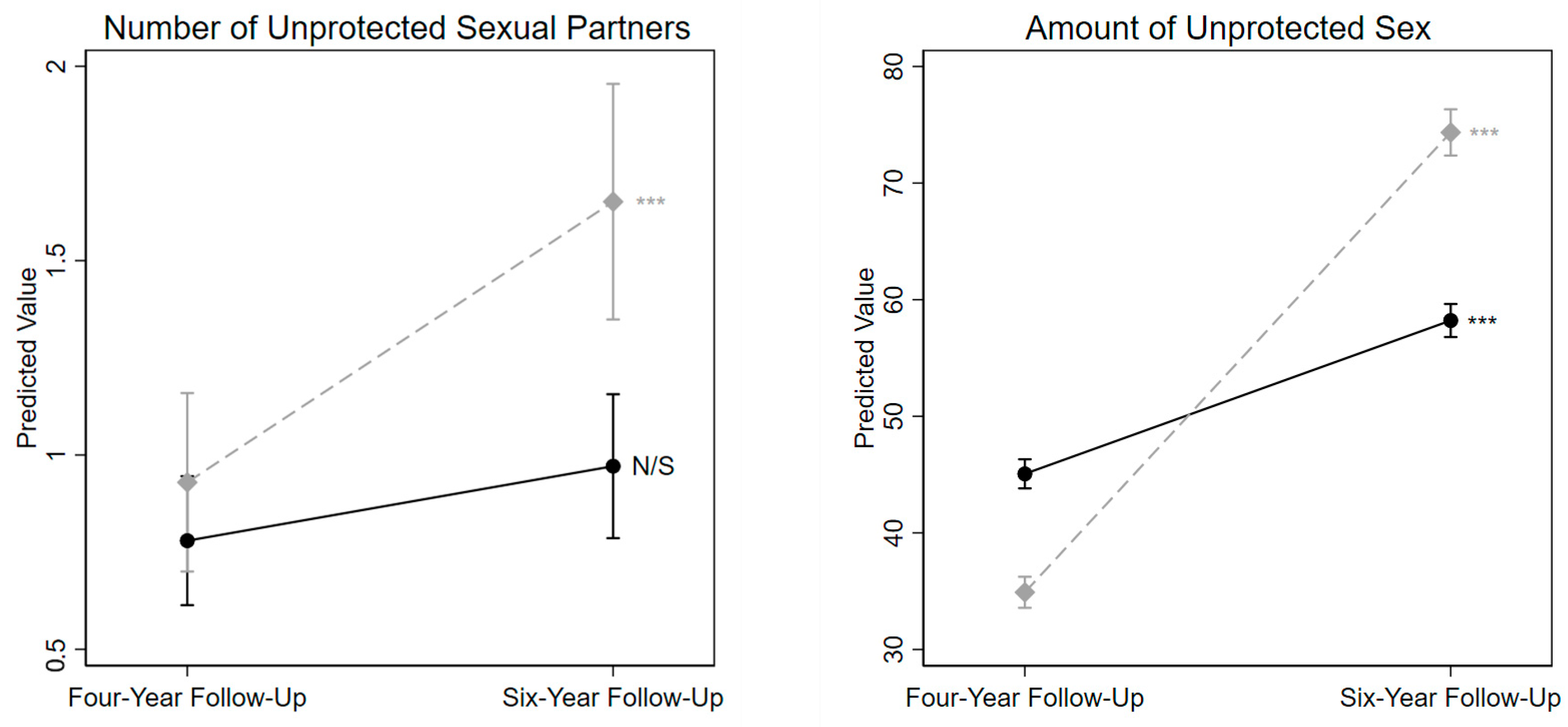

3.3. Aim 2: Outcomes Associated with HIV Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Baseline Factors Predicting HIV Testing

4.2. Behavior Change Between Those Newly and Never Tested for HIV

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abram, K. M., Stokes, M. L., Welty, L. J., Aaby, D. A., & Teplin, L. A. (2017). Disparities in HIV/AIDS risk behaviors after youth leave detention: A 14-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics, 139(2), e20160360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AIDSvu. (2022). 2022 National new diagnoses. Available online: https://aidsvu.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/AIDSVu_National_NewDX_2022-20240916.xlsx (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Auslander, W. F., McMillen, J. C., Elze, D., Thompson, R., Jonson-Reid, M., & Stiffman, A. (2002). Mental health problems and sexual abuse among adolescents in foster care: Relationship to HIV risk behaviors and intentions. AIDS and Behavior, 6(4), 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenko, S., Dembo, R., Rollie, M., Childs, K., & Salvatore, C. (2009). Detecting, preventing, and treating sexually transmitted diseases among adolescent arrestees: An unmet public health need. American Journal of Public Health, 99(6), 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocknek, E. L., Brophy-Herb, H. E., Fitzgerald, H. E., Schiffman, R. F., & Vogel, C. (2014). Stability of biological father presence as a proxy for family stability: Cross-racial associations with the longitudinal development of emotion regulation in toddlerhood. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(4), 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, A. D., Schmiege, S. J., & Broaddus, M. R. (2009). HIV risk reduction among detained adolescents: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics, 124(6), e1180–e1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, J., Wendt, M., & Bakos, A. (2019). Understanding and addressing health disparities and health needs of justice-involved populations. Public Health Reports, 134, 3S–7S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, F., Galanek, J. D., Kretschmar, J. M., & Flannery, D. J. (2015). The impact of neighborhood disorganization on neighborhood exposure to violence, trauma symptoms, and social relationships among at-risk youth. Social Science & Medicine, 146, 300–306. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). AtlasPlus. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/about/atlasplus.html (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Derogatis, L. R., & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The brief symptom inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donenberg, G. R., Emerson, E., Mackesy-Amiti, M. E., & Udell, W. (2015). HIV-risk reduction with juvenile offenders on probation. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(6), 1672–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnham, P. G., Hutchinson, A. B., Sansom, S. L., & Branson, B. M. (2008). Comparing the costs of HIV screening strategies and technologies in health-care settings. Public Health Reports, 123Suppl. S3, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galobardes, B., Lynch, J., & Smith, G. D. (2007). Measuring socioeconomic position in health research. British Medical Bulletin, 81(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, W., Brown, L. K., Lescano, C. M., Kell, H., Spalding, K., DiClemente, R., & Donenberg, G. (2009). Parent–adolescent sexual communication: Associations of condom use with condom discussions. AIDS and Behavior, 13(5), 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney-Caron, E., Brown, L. K., & Tolou-Shams, M. (2020). Brief Report: HIV Testing and Risk Among Justice-Involved Youth. AIDS and Behavior, 25(5), 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenigl, M., Anderson, C. M., Green, N., Mehta, S. R., Smith, D. M., & Little, S. J. (2015). Repeat HIV-testing is associated with an increase in behavioral risk among men who have sex with men: A cohort study. BMC Medicine, 13(1), 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingshead, A. B. (1957). Two factor index of social position (vol. 101). Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga, D., Esbensen, F.-A., & Weiher, A. W. (1991). Are there multiple paths to delinquency. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 82, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Iroh, P. A., Mayo, H., & Nijhawan, A. E. (2015). The HIV care cascade before, during, and after incarceration: A systematic review and data synthesis. American Journal of Public Health, 105(7), e5–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques-Aviñó, C., Garcia de Olalla, P., Gonzalez Antelo, A., Fernandez Quevedo, M., Romaní, O., & Caylà, J. A. (2019). The theory of masculinity in studies on HIV. A systematic review. Global Public Health, 14(5), 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamb, M. L., Fishbein, M., Douglas, J. M., Jr., Rhodes, F., Rogers, J., Bolan, G., Zenilman, J., Hoxworth, T., Malotte, C. K., & Iatesta, M. (1998). Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 280(13), 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., Lowry, R., Chyen, D., Whittle, L., & Thornton, J. (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, B. J., & Miller, K. S. (2012). Parents as HIV/AIDS educators. In Family and HIV/AIDS (pp. 97–120). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, A. E., Lally, M. A., Choko, A. T., Inwani, I. W., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2015). HIV testing and linkage to services for youth. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18, 19433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, N., Friestad, C., & Klepp, K. I. (2001). Adolescents’ proxy reports of parents’ socioeconomic status: How valid are they? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 55(10), 731–737. [Google Scholar]

- Marcell, A. V., Ford, C. A., Pleck, J. H., & Sonenstein, F. L. (2007). Masculine beliefs, parental communication, and male adolescents’ health care use. Pediatrics, 119(4), e966–e975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metsch, L. R., Feaster, D. J., Gooden, L., Schackman, B. R., Matheson, T., Das, M., Golden, M. R., Huffaker, S., Haynes, L. F., & Tross, S. (2013). Effect of risk-reduction counseling with rapid HIV testing on risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections: The AWARE randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 310(16), 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD). (2022). Compendium of Evidence-Informed Approaches to Improving Health Outcomes for People Living with HIV. Available online: https://targethiv.org/library/cie-compendium (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (2018). Law enforcement and juvenile crime: Juvenile arrests. Available online: https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/crime/qa05101.asp?qaDate=2018 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Patrick, M. E., O’Malley, P. M., Johnston, L. D., Terry-McElrath, Y. M., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2012). HIV/AIDS risk behaviors and substance use by young adults in the United States. Prevention Science, 13(5), 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randolph, S. D., Coakley, T., Shears, J., & Thorpe, R. J., Jr. (2017). African-American Fathers’ Perspectives on Facilitators and Barriers to Father–Son Sexual Health Communication. Research in Nursing & Health, 40(3), 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, S., Mann, L., Alonzo, J., Downs, M., Abraham, C., Miller, C. J., Stowers, J., Ramsey, B., Siman, F., Song, E., Vissman, A., Eng, E., & Reboussin, B. (2014). CBPR to prevent HIV within racial/ethnic, sexual, and gender minority communities: Successes with long-term sustainability. In Innovations in HIV prevention research and practice through community engagement (pp. 135–160). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J., & Robillard, A. (2013). The least of these: Chronic exposure to violence and HIV risk behaviors among African American male violent youth offenders detained in an adult jail. Journal of Black Psychology, 39(1), 28–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, A. J., Kelly, K. M., Weinstein, N. D., & O’Leary, A. (1999). Increasing the salience of risky sexual behavior: Promoting interest in HIV-antibody testing among heterosexually active young adults 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(3), 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnall, R., Rojas, M., & Travers, J. (2015). Understanding HIV testing behaviors of minority adolescents: A health behavior model analysis. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 26(3), 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C. A., Mulvey, E. P., Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., Losoya, S. H., Hecker, T., Chassin, L., & Knight, G. P. (2004). Operational lessons from the pathways to desistance project. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2(3), 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selner-O’Hagan, M. B., Kindlon, D. J., Buka, S. L., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. J. (1998). Assessing exposure to violence in urban youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39(2), 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S. (2004). The behavioral consequences of HIV testing: An experimental investigation. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 23(1), 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2021). Stata statistical software: MP parallel edition, release 17. StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Sulat, J. S., Prabandari, Y. S., Sanusi, R., Hapsari, E. D., & Santoso, B. (2018). The impacts of community-based HIV testing and counselling on testing uptake: A systematic review. Journal of Health Research, 32(2), 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplin, L. A., Mericle, A. A., McClelland, G. M., & Abram, K. M. (2003). HIV and AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees: Implications for public health policy. American Journal of Public Health, 93(6), 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolou-Shams, M., Brown, L. K., Gordon, G., Fernandez, I., & Project SHIELD Study Group. (2007). Arrest history as an indicator of adolescent/young adult substance use and HIV risk. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(1), 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolou-Shams, M., Brown, L. K., Houck, C., Lescano, C. M., & Group, P. S. S. (2008). The association between depressive symptoms, substance use, and HIV risk among youth with an arrest history. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69(1), 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolou-Shams, M., Conrad, S., Louis, A., Shuford, S. H., & Brown, L. K. (2015). HIV testing among non-incarcerated substance-abusing juvenile offenders. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 27(4), 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolou-Shams, M., Harrison, A., Hirschtritt, M. E., Dauria, E., & Barr-Walker, J. (2019). Substance use and HIV among justice-involved youth: Intersecting risks. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 16(1), 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2025). HIV: US Statistics. Available online: https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Voisin, D. R. (2005). The relationship between violence exposure and HIV sexual risk behaviors: Does gender matter? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(4), 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voisin, D. R., Jenkins, E. J., & Takahashi, L. (2011). Toward a conceptual model linking community violence exposure to HIV-related risk behaviors among adolescents: Directions for research. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(3), 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhardt, L. S. (2005). HIV diagnosis and risk behavior. In Positive prevention (pp. 29–63). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Welty, L. J., Harrison, A. J., Abram, K. M., Olson, N. D., Aaby, D. A., McCoy, K. P., Washburn, J. J., & Teplin, L. A. (2016). Health disparities in drug-and alcohol-use disorders: A 12-year longitudinal study of youths after detention. American Journal of Public Health, 106(5), 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westergaard, R. P., Spaulding, A. C., & Flanigan, T. P. (2013). HIV among persons incarcerated in the US: A review of evolving concepts in testing, treatment and linkage to community care. Current opinion in Infectious Diseases, 26(1), 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| OR | SE | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Factors | ||||

| Mental Health Problem Index | 1.250 | 0.175 | 0.110 | 0.950, 1.645 |

| Number of Sexual Partners | 1.005 | 0.008 | 0.479 | 0.991, 1.020 |

| Total Exposure to Violence | 1.043 | 0.041 | 0.285 | 0.966, 1.125 |

| Any Lifetime Non-Marijuana Drug Use | 1.102 | 0.240 | 0.657 | 0.718, 1.690 |

| Any Lifetime Substance Use Treatment | 1.427 | 0.362 | 0.161 | 0.868, 2.344 |

| Contextual Factors | ||||

| Biological Father Present | 0.681 | 0.133 | 0.049 ** | 0.465, 0.998 |

| Lifetime Number of Arrests | 1.056 | 0.378 | 0.127 | 0.985, 1.133 |

| Age at First Arrest | 0.918 | 0.061 | 0.199 | 0.806, 1.046 |

| Any Prior Incarceration | 1.083 | 0.228 | 0.705 | 0.717, 1.636 |

| Lifetime Offending Variety | 4.735 | 3.039 | 0.015 ** | 1.346, 16.658 |

| Demographic Factors | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White (ref) | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Black | 1.536 | 0.473 | 0.164 | 0.839, 2.801 |

| Latinx | 0.806 | 0.201 | 0.385 | 0.494, 1.312 |

| Other Racial Category/Multiracial | 0.073 | 0.312 | 0.468 | 0.320, 1.688 |

| Socioeconomic Disadvantage | 0.997 | 0.008 | 0.683 | 0.982, 1.012 |

| Age at Baseline | 1.028 | 0.096 | 0.766 | 0.857, 1.234 |

| Study Site Location (Philadelphia vs. Phoenix) | 3.066 | 0.757 | <0.001 *** | 1.890, 4.974 |

| Predictors | Outcome Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance Use Behavior | Risky Sexual Behavior | |||||

| Alcohol Use Frequency (N = 197) | Marijuana Use Frequency (N = 197) | Cigarette Use Frequency (N = 196) | Any Non−Marijuana Drug Use (N = 185) | Number of Unprotected Sexual Partners (N = 177) | Number of Times Had Unprotected Sex (N = 191) | |

| (B, p) | (B, p) | (B, p) | (B, p) | (B, p) | (B, p) | |

| Newly Tested vs. Never Tested | 5.049, 0.239 | 0.053, 0.574 | 0.715, 0.235 | 1.278, 0.630 | 0.523, 0.001 *** | 0.467, <0.001 *** |

| Prior Level of Outcome Variable | 0.403, <0.001 *** | 0.161, <0.001 *** | 0.569, <0.001 *** | 15.812, <0.001 *** | 0.171, <0.001 *** | 0.005, <0.001 *** |

| Individual Factors | ||||||

| Mental Health Problem Index | 3.190, 0.349 | 0.042, 0.597 | 3.902, 0.416 | 0.560, 0.224 | 0.318, 0.004 *** | 0.166, <0.001 *** |

| Number of Sexual Partners | −0.042, 0.845 | −0.003, 0.567 | −0.232, 0.440 | 1.000, 0.996 | 0.002, 0.794 | 0.002, 0.136 |

| Total Exposure to Violence | 1.509, 0.098 | 0.008, 0.708 | 0.030, 0.982 | 1.304, 0.041 ** | −0.022, 0.519 | −0.024, <0.001 *** |

| Any Lifetime Non-Marijuana Drug Use 1 | −0.209, 0.967 | 0.231, 0.039 ** | 1.780, 0.798 | N/A | 0.321, 0.055 | 0.674, <0.001 *** |

| Any Lifetime Substance Use Treatment | 7.988, 0.210 | −0.030, 0.811 | 11.258, 0.212 | 2.227, 0.235 | 0.290, 0.185 | −0.265, <0.001 *** |

| Contextual Factors | ||||||

| Biological Father Present | 0.300, 0.945 | 0.067, 0.476 | 7.634, 0.212 | 1.357, 0.554 | −0.087, 0.585 | 0.084, <0.001 *** |

| Lifetime Number of Arrests | −0.842, 0.388 | −0.042, 0.090 | 1.049, 0.451 | 0.779, 0.076 | −0.005, 0.880 | −0.046, <0.001 *** |

| Age at First Arrest | −0.730, 0.657 | −0.039, 0.224 | 2.475, 0.292 | 0.654, 0.031 ** | 0.017, 0.764 | −0.078, <0.001 *** |

| Any Prior Incarceration | −10.326, 0.041 ** | 0.109, 0.347 | −5.473, 0.436 | 0.631, 0.478 | −0.616, 0.001 *** | 0.166, <0.001 *** |

| Lifetime Offending Variety | 7.067, 0.663 | 0.254, 0.473 | 25.662, 0.259 | 42.330, 0.047 ** | 0.348, 0.529 | −0.817, <0.001 *** |

| Demographic Factors | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White (ref) | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Black | −3.154, 0.695 | −0.152, 0.383 | −22.170, 0.050 ** | 0.078, 0.023 ** | −0.589, 0.081 | −0.240, <0.001 *** |

| Latinx | −3.976, 0.485 | 0.102, 0.413 | −15.543, 0.052 | 0.412, 0.174 | −0.079, 0.671 | 0.226, <0.001 *** |

| Multiracial/Other Racial Category | −13.662, 0.153 | −0.394, 0.104 | 1.594, 0.906 | N/A | −0.662, 0.095 | 0.456, <0.001 *** |

| Socioeconomic Disadvantage | 0.112, 0.573 | −0.013, 0.004 *** | 0.154, 0.582 | 0.997, 0.890 | 0.005, 0.428 | 0.001, 0.143 |

| Concurrent Street Time | 11.524, 0.062 | 0.186, 0.223 | 17.116, 0.047 ** | 6.854, 0.056 | 0.546, 0.040 ** | 0.865, <0.001 *** |

| Age at Four-Year Follow-up | −0.938, 0.666 | 0.095, 0.048 ** | −1.784, 0.573 | 1.477, 0.140 | 0.180, 0.026 ** | −0.049, <0.001 *** |

| Study Site Location (Philadelphia vs. Phoenix) | −13.672, 0.039 ** | 0.338, 0.014 ** | 7.168, 0.441 | 3.079, 0.134 | −0.300, 0.283 | 0.177, <0.001 *** |

| Outcome Variable | Time x Testing Category (i.e., Newly Tested v. Never Tested) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | p | 95% CI | |

| Substance Use Behavior | |||

| Alcohol Use Frequency | 6.846 | 0.110 | −1.558, 15.251 |

| Marijuana Use Frequency | −0.006 | 0.947 | −0.185, 0.173 |

| Cigarette Use Frequency | 1.814 | 0.775 | −10.613, 14.241 |

| Any Non-Marijuana Drug Use | 0.456 | 0.491 | −0.842, 1.754 |

| Risky Sexual Behavior | |||

| Number of Unprotected Sexual Partners | 0.355 | 0.059 + | −0.133, 0.723 |

| Number of Times had Unprotected Sex | 0.500 | <0.001 *** | 0.451, 0.550 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riano, N.S.; Beardslee, J.; Cauffman, E. A Lost Opportunity to Reduce Future Risk Among Justice-Involved Young Adults Through HIV Testing and Counseling. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050578

Riano NS, Beardslee J, Cauffman E. A Lost Opportunity to Reduce Future Risk Among Justice-Involved Young Adults Through HIV Testing and Counseling. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):578. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050578

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiano, Nicholas S., Jordan Beardslee, and Elizabeth Cauffman. 2025. "A Lost Opportunity to Reduce Future Risk Among Justice-Involved Young Adults Through HIV Testing and Counseling" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050578

APA StyleRiano, N. S., Beardslee, J., & Cauffman, E. (2025). A Lost Opportunity to Reduce Future Risk Among Justice-Involved Young Adults Through HIV Testing and Counseling. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050578