Materialistic Tendencies Lead to Less Empathy from Others

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Observer’s Empathy Toward Materialists Is Influenced by Their Materialistic Traits

1.2. The Materialism of the Empathy Target Reduces Observer Empathy Through Perceived Morality and Perceived Warmth

1.2.1. Observers’ Perceived Morality of Materialists

1.2.2. Observers’ Perceived Warmth of Materialists

2. Research Overview

3. Pretest 1: Development and Validation of Materials for Study 1

4. Study 1

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Research Design

4.1.2. Participants

4.1.3. Procedure and Materials

4.1.4. Measures

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Manipulation Check and Attention Check

4.2.2. Independent Samples t-Test Results

5. Study 2

5.1. Method

5.1.1. Research Design

5.1.2. Participants

5.1.3. Procedure and Materials

5.1.4. Measures

5.2. Results

5.2.1. Manipulation Check and Attention Check

5.2.2. ANOVA Results

5.3. Discussion (Studies 1 and 2)

6. Study 3

6.1. Methods

6.1.1. Research Design

6.1.2. Participants

6.1.3. Procedure and Materials

6.1.4. Measures

6.2. Results

6.2.1. Manipulation Check and Attention Check

6.2.2. ANOVA Results

6.3. Discussion

7. Pretest 2: Development and Validation of New Materials for Study 4

7.1. Development of Materialism Vignettes

7.2. Development and Selection of Misfortune Scenarios

7.3. Validation Procedure

7.4. Results

7.5. Conclusion

8. Study 4

8.1. Method

8.1.1. Research Design

8.1.2. Participants

8.1.3. Procedure and Materials

8.1.4. Measures

8.2. Results

8.2.1. Manipulation Check and Attention Check

8.2.2. ANOVA Results

- (1)

- Perceived Morality

- (2)

- Perceived Warmth

- (3)

- Observer Empathy

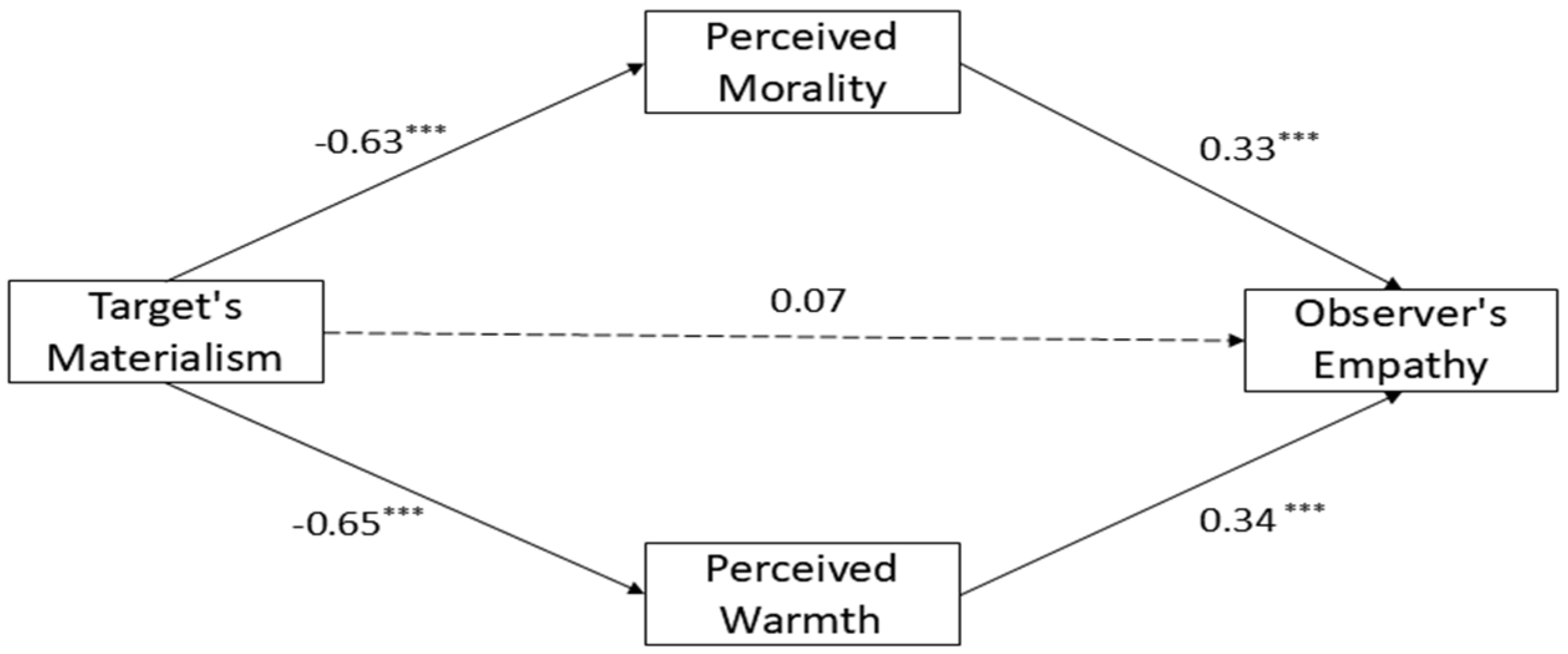

8.2.3. Mediation Analysis Results

- Mediation Path Analysis

- (1)

- Mediation Effect of Perceived Morality

- (2)

- Mediation Effect of Perceived Warmth

- (3)

- Total Indirect Effect

8.3. Discussion

9. General Discussion

9.1. Contributions to Theory

9.2. Contributions to Practice

9.3. Limitations and Future Directions

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Abele, A. E., & Hauke, N. (2020). Comparing the facets of the big two in global evaluation of self versus other people. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50(5), 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, A. E., Hauke, N., Peters, K., Louvet, E., Szymkow, A., & Duan, Y. (2016). Facets of the fundamental content dimensions: Agency with competence and assertiveness—Communion with warmth and morality. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2007). Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azibo, D. A. Y. (2013). Unmasking materialistic depression as a mental health problem: Its effect on depression and materialism in an African-United States undergraduate sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(2), 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. (2017). Exchange and power in social life. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, M., & Riva, P. (2017). Predicting pleasure at others’ misfortune: Morality trumps sociability and competence in driving deservingness and schadenfreude. Motivation and Emotion, 41(2), 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, M., Sacchi, S., Rusconi, P., & Goodwin, G. P. (2021). The primacy of morality in impression development: Theory, research, and future directions. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 64, pp. 187–262). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, E., Landry, T., & Wood, C. (2007). Beyond just being there: An examination of the impact of attitudes, materialism, and self-esteem on the quality of helping behavior in youth volunteers. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 18(2), 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L. M., Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (2006). Affective reactions to pictures of ingroup and outgroup members. Biological Psychology, 71(3), 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C. D., Hutcherson, C. A., Ferguson, A. M., Scheffer, J. A., Hadjiandreou, E., & Inzlicht, M. (2019). Empathy is hard work: People choose to avoid empathy because of its cognitive costs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(6), 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, J. (2018). Explaining females’ envy toward social media influencers. Media Psychology, 21(2), 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A., Hunt, J. M., & Kernan, J. B. (2000). Social character of materialism. Psychological Reports, 86(Suppl. S3), 1147–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R. M., & Fernando, M. (2013). The role of spiritual well-being and materialism in determining consumers’ ethical beliefs: An empirical study with Australian consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 113, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cikara, M., Bruneau, E. G., & Saxe, R. R. (2011). Us and them: Intergroup failures of empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P., & Cohen, J. (2013). Life values and adolescent mental health. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J. A., & Rodell, J. B. (2011). Justice, trust, and trustworthiness: A longitudinal analysis integrating three theoretical perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1183–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F., Ma, N., & Luo, Y.-j. (2016). Moral judgment modulates neural responses to the perception of other’s pain: An ERP study. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 20851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deska, J. C., Kunstman, J., Lloyd, E. P., Almaraz, S. M., Bernstein, M. J., Gonzales, J., & Hugenberg, K. (2020). Race-based biases in judgments of social pain. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 88, 103964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbruch, A. B., & Krasnow, M. M. (2022). Why warmth matters more than competence: A new evolutionary approach. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(6), 1604–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, F. J. (2003). How much should I give and how often? The effects of generosity and frequency of favor exchange on social status and productivity. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5), 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentina, E., Shrum, L. J., & Lowrey, T. M. (2018a). Coping with Loneliness through materialism: Strategies matter for adolescent development of unethical behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(1), 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentina, E., Shrum, L. J., Lowrey, T. M., Vitell, S. J., & Rose, G. M. (2018b). An integrative model of the influence of parental and peer support on consumer ethical beliefs: The mediating role of self-esteem, power, and materialism. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(4), 1173–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Zheng, L., Zhang, W., Zhu, L., Li, J., Wang, Q., Dienes, Z., & Yang, Z. (2012). Empathic neural responses to others’ pain depend on monetary reward. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(5), 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Horgas, A. L., & Elliott, A. F. (2004). Pain assessment and management in persons with dementia. Nursing Clinics, 39(3), 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, E. D., Pandelaere, M., Pieters, R. G., & Shrum, L. (2023). Materialism and life satisfaction relations between and within people over time: Results of a three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 33(3), 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jieting, C., Bin, Z., & Xinjian, W. (2015). Morality: A new dimension of stereotype content. Psychological Exploration, 35(5), 442–447. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S. V., & Ryu, E. (2020). “I’ll buy what she’s# wearing”: The roles of envy toward and parasocial interaction with influencers in Instagram celebrity-based brand endorsement and social commerce. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T. (2003). The high price of materialism. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser, T. (2016). Materialistic values and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 67(1), 489–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopiś, N., Francuz, P., Zabielska-Mendyk, E., & Augustynowicz, P. (2020). Feeling other people’s pain: An event-related potential study on facial attractiveness and emotional empathy. Advances in Cognitive Psychology, 16(2), 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.-C., & Lu, C.-J. (2010). Moral philosophy, materialism, and consumer ethics: An exploratory study in Indonesia. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, B. J., & Kteily, N. S. (2018). (Anti-)egalitarianism differentially predicts empathy for members of advantaged versus disadvantaged groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(5), 665–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M., Zhang, M., Huang, N., & Fu, X. (2023). Effects of materialism on adolescents’ prosocial and aggressive behaviors: The mediating role of empathy. Behavioral Sciences, 13(10), 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos Devesa, A. S. (2022). The high-status compassion bias: When and why do people assist high-and low-status victims? University of Nottingham. [Google Scholar]

- Morelli, S. A., Lieberman, M. D., & Zaki, J. (2015). The emerging study of positive empathy. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(2), 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muncy, J. A., & Eastman, J. K. (1998). Materialism and consumer ethics: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(2), 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B. C., Van Leeuwen, M. L., Van Baaren, R. B., Bekkering, H., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2013). Empathy is a beautiful thing: Empathy predicts imitation only for attractive others. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 54(5), 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purutçuoğlu, e., & Doğan, İ. (2017). The effect of working children’s materialistic tendencies on their friendship relations. Journal of International Social Research, 10(51), 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M. L. (1994). Special possessions and the expression of material values. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(3), 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, P., Brambilla, M., & Vaes, J. (2016). Bad guys suffer less (social pain): Moral status influences judgements of others’ social suffering. British Journal of Social Psychology, 55(1), 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roets, A., Van Hiel, A., & Cornelis, I. (2006). Does materialism predict racism? Materialism as a distinctive social attitude and a predictor of prejudice. European Journal of Personality, 20(2), 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, L., & Dziurawiec, S. (2001). Materialism and its relationship to life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 55, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, J. A., Cameron, C. D., & Inzlicht, M. (2022). Caring is costly: People avoid the cognitive work of compassion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 151(1), 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K. M., & Kasser, T. (1995). Coherence and congruence: Two aspects of personality integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(3), 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, E. G., Diener, E., & Robinson, M. D. (2004). Why are materialists less satisfied? In T. Kasser, & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Psychology and consumer culture: The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world (pp. 29–48). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, C., Bolick, B., Wright, K., & Hamilton, R. (2016). Understanding compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A review of current literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 48(5), 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. M., & Kasser, T. (2013). Generational changes in materialism and work centrality, 1976–2007: Associations with temporal changes in societal insecurity and materialistic role modeling. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(7), 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boven, L., Campbell, M. C., & Gilovich, T. (2010). Stigmatizing materialism: On stereotypes and impressions of materialistic and experiential pursuits. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(4), 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Harris, P. L., Pei, M., & Su, Y. (2023). Do bad people deserve empathy? Selective empathy based on targets’ moral characteristics. Affective Science, 4(2), 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciszke, B., Abele, A. E., & Baryla, W. (2009). Two dimensions of interpersonal attitudes: Liking depends on communion, respect depends on agency. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(6), 973–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L., Zeng, X., & Li, J. (2024). The effect of materialism on unethical behaviour: The mediating role of self-control. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 27(4), 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, J. (2014). Empathy: A motivated account. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1608–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y., & Mick, D. G. (2019). Neutralizing the shamefulness judgements of materialistic buyer behavior: The role of price promotions and the smart-shopper attribution. Psychology & Marketing, 36(11), 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | N | Mean | SD | ANOVA | Post Hoc (LSD) Comparisons (Mean Difference [p]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 88 | 27.08 | 3.84 | F(3, 358) = 16.46 p < 0.001 ηp2 = 0.121 | High vs. mod = 2.52 *** (p < 0.001) |

| Moderate | 93 | 26.48 | 4.52 | High vs. none = 4.41 *** (p < 0.001) | |

| High | 94 | 23.97 | 5.54 | Low vs. mod = 0.60 (p = 0.36) | |

| None | 87 | 28.38 | 3.42 | Low vs. none = 1.30 (p = 0.049) |

| Ma | So | N | M(e) | SD | Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | η2p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low | 97 | 27.81 | 4.61 | Ma | 733.22 | 1 | 733.22 | 19.00 | <0.001 | 0.049 |

| Low | High | 96 | 24.07 | 6.54 | So | 718.90 | 1 | 718.90 | 18.63 | <0.001 | 0.048 |

| High | Low | 88 | 24.05 | 6.91 | In | 88.15 | 1 | 88.15 | 2.29 | 0.132 | 0.006 |

| High | High | 94 | 22.24 | 6.60 | — | — | — |

| Variable | Low Materialism M(SD) N = 389 | High Materialism M(SD) N = 396 | F | p | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empathy | 29.41 (3.14) | 25.42 (6.49) | 119.6 | <0.001 | 0.133 |

| Perceived Morality | 17.06 (1.99) | 11.82 (4.06) | 524.23 | <0.001 | 0.401 |

| Perceived Warmth | 25.50 (3.01) | 17.23 (6.09) | 577.98 | <0.001 | 0.425 |

| Path | B | SE | t/BootSE | p | 95% CI | β (Partially Std.) | % of Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | −1.99 | 0.18 | −10.94 | <0.001 | [−2.35, −1.64] | 100% | |

| Direct effect | 0.36 | 0.21 | 1.73 | 0.085 | [−0.05, 0.76] | ||

| Perceived morality (a1) | −2.62 | 0.11 | −22.9 | <0.001 | −0.63 | ||

| Perceived morality → empathy (b1) | 0.43 | 0.09 | 5 | <0.001 | 0.33 | ||

| Indirect via morality (a1b1) | −1.13 | 0.25 | [−1.63, −0.65] | −0.21 | 48.11% | ||

| Perceived warmth (a2) | −4.13 | 0.17 | −24.04 | <0.001 | −0.65 | ||

| Perceived warmth → empathy (b2) | 0.3 | 0.06 | 5.14 | <0.001 | 0.34 | ||

| Indirect via warmth (a2b2) | −1.22 | 0.23 | [−1.70, −0.77] | −0.22 | 51.89% | ||

| Total indirect effect | −2.35 | 0.22 | [−2.79, −1.95] | 117.90% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, W.; Wang, Y.; Cui, L.; Feng, N. Materialistic Tendencies Lead to Less Empathy from Others. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050577

Zeng W, Wang Y, Cui L, Feng N. Materialistic Tendencies Lead to Less Empathy from Others. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):577. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050577

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Weinan, Yan Wang, Lijuan Cui, and Ningning Feng. 2025. "Materialistic Tendencies Lead to Less Empathy from Others" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050577

APA StyleZeng, W., Wang, Y., Cui, L., & Feng, N. (2025). Materialistic Tendencies Lead to Less Empathy from Others. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050577