Temporal Landmarks and Nostalgic Consumption: The Role of the Need to Belong

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Nostalgic Consumption as a Coping Strategy to Counteract Social Anxiety

2.2. End Temporal Landmarks and Nostalgic Consumption

2.3. End Temporal Landmarks and Need to Belong

2.4. Need to Belong and Nostalgic Consumption

3. Overview of Studies

3.1. Pilot Study

3.1.1. Research Design and Participants

3.1.2. Procedure

3.1.3. Results

3.2. Study 1

3.2.1. Research Design and Participants

3.2.2. Procedure

3.2.3. Results

3.3. Study 2

3.3.1. Research Design and Participants

3.3.2. Procedure

3.3.3. Results

3.4. Study 3

3.4.1. Research Design and Participants

3.4.2. Procedure

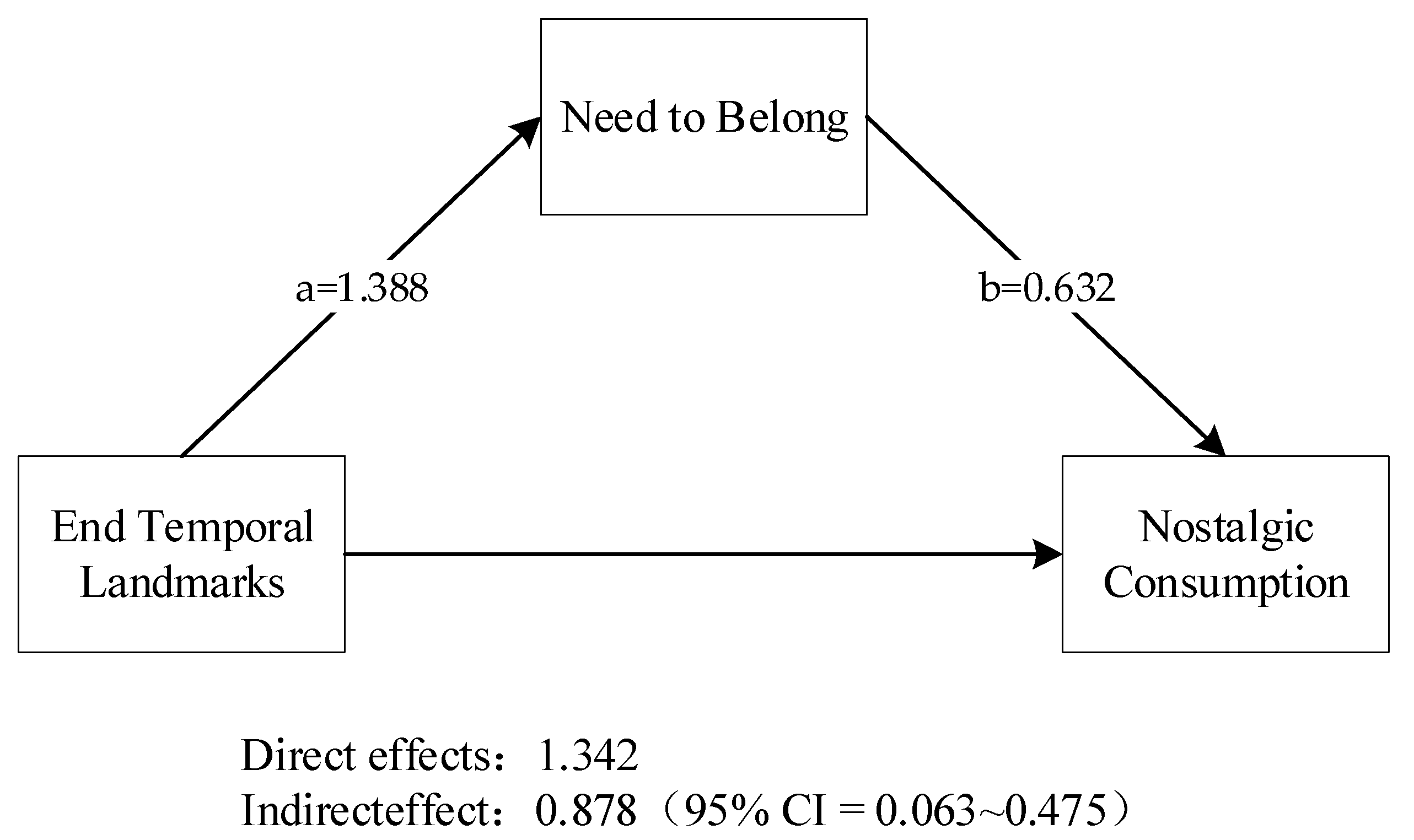

3.4.3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Managerial Implications

5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Measurement Scales

Appendix A.1.1. Manipulation Check Measure for Perception of Nostalgia (Pilot Study) (Adapted from Loveland et al. [57]):

- Does this advertisement remind you of the past?

- Please rate the nostalgic feeling that you have when reading this ad.

Appendix A.1.2. Need to Belong (A 5-Point Scale Adapted from Leary et al. [57]. (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.914)

- 3.

- If other people don’t seem to accept me, I don’t let it bother me. (R)

- 4.

- I try hard not to do things that will make other people avoid or reject me.

- 5.

- I seldom worry about whether other people care about me. (R)

- 6.

- I need to feel that there are people I can turn to in times of need.

- 7.

- I want other people to accept me.

- 8.

- I do not like being alone.

- 9.

- Being apart from my friends for long periods of time does not bother me. (R)

- 10.

- I have a strong “need to belong”.

- 11.

- It bothers me a great deal when I am not included in other people’s plans.

- 12.

- My feelings are easily hurt when I feel that others do not accept me.

References

- Kindred, R.; Bates, G.W. The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baines, P.; Brady, M.; Jain, S. Guest Editorial: Pandemic Aftershock—The Challenges of Rapid Technology Adoption and Social Distancing for Interactive Marketing Practice. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M. Viewpoint–a Big Opportunity for Interactive Marketing Post-COVID-19. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, N.; Mulye, R.; Japutra, A. How Do Consumers Interact with Social Media Influencers in Extraordinary Times? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Fishbach, A. Feeling Lonely Increases Interest in Previously Owned Products. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 58, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Day, E.B.; Heimberg, R.G. Social Media Use, Social Anxiety, and Loneliness: A Systematic Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 3, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Wang, J.; Santana, S. Nostalgia: Triggers and Its Role on New Product Purchase Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 135, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C.; Wildschut, T. Finding Meaning in Nostalgia. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2018, 22, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layous, K.; Kurtz, J.L. Nostalgia: A Potential Pathway to Greater Well-Being. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 49, 101548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M. Sketch for a Phenomenology of Nostalgia. Hum. Stud. 2023, 46, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, W.A.P.; Sedikides, C.; Wildschut, T. Adverse Weather Evokes Nostalgia. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 44, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seehusen, J.; Cordaro, F.; Wildschut, T.; Sedikides, C.; Routledge, C.; Blackhart, G.C.; Epstude, K.; Vingerhoets, A.J. Individual Differences in Nostalgia Proneness: The Integrating Role of the Need to Belong. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2013, 55, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, W.A.; Igou, E.R.; Sedikides, C. In Search of Meaningfulness: Nostalgia as an Antidote to Boredom. Emotion 2013, 13, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M. The Psychology of Nostalgia during COVID-19 Psychology Today. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mind-brain-and-value/202005/the-psychology-nostalgia-during-COVID-19 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Wang, C.L. New Frontiers and Future Directions in Interactive Marketing: Inaugural Editorial. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, R.M.; Holbrook, M.B. Nostalgia for Early Experience as a Determinant of Consumer Preferences. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, G. Nostalgic Collections. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2017, 20, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarten, E.; Wei, Z. Nostalgia and Consumer Behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 49, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Limbu, Y.B.; Fang, X. Consumer Brand Engagement on Social Media in the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Roles of Country-of-Origin and Consumer Animosity. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Milkman, K.L.; Riis, J. Put Your Imperfections Behind You: Temporal Landmarks Spur Goal Initiation When They Signal New Beginnings. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peetz, J.; Wilson, A.E. The Post-Birthday World: Consequences of Temporal Landmarks for Temporal Self-Appraisal and Motivation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Mou, Y. Consumer Insecurity and Preference for Nostalgic Products: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2406–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, B.B. Historical and Personal Nostalgia in Advertising Text: The Fin. de Siècle Effect. J. Advert. 1992, 21, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-N.; Kim, H.E.; Youn, N. Together or Alone on the Prosocial Path amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Partitioning Effect in Experiential Consumption. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Sarkar, J.G.; Sarkar, A. Hallowed Be Thy Brand: Measuring Perceived Brand Sacredness. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 733–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jang, S.; Choi, W.; Youn, C.; Lee, Y. Contactless Service Encounters among Millennials and Generation Z: The Effects of Millennials and Gen Z Characteristics on Technology Self-Efficacy and Preference for Contactless Service. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveland, K.E.; Smeesters, D.; Mandel, N. Still Preoccupied with 1995: The Need to Belong and Preference for Nostalgic Products. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, C.; Wildschut, T.; Sedikides, C.; Juhl, J.; Arndt, J. The Power of the Past: Nostalgia as a Meaning-Making Resource. Memory 2012, 20, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askelund, A.D.; Schweizer, S.; Goodyer, I.M.; van Harmelen, A.-L. Positive Memory Specificity Is Associated with Reduced Vulnerability to Depression. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildschut, T.; Sedikides, C.; Arndt, J.; Routledge, C. Nostalgia: Content, Triggers, Functions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 975–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcho, K.I. Nostalgia: A Psychological Perspective. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1995, 80, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcho, K.I. Nostalgia: The Bittersweet History of a Psychological Concept. Hist. Psychol. 2013, 16, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Temporal Construal. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The Role of Feasibility and Desirability Considerations in near and Distant Future Decisions: A Test of Temporal Construal Theory. J. Per. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Kader, M.S.; Kim, S. Let’s Play with Emojis! How to Make Emojis More Effective in Social Media Advertising Using Promocodes and Temporal Orientation. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, M.S. The Role of Temporal Landmarks in Autobiographical Memory Processes. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurbat, M.A.; Shevell, S.K.; Rips, L.J. A Year’s Memories: The Calendar Effect in Autobiographical Recall. Mem. Cogn. 1998, 26, 532–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, J.L. Looking to the Future to Appreciate the Present: The Benefits of Perceived Temporal Scarcity. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1238–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Mogilner, C. Happiness from Ordinary and Extraordinary Experiences. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, E.; Ellsworth, P.C. Saving the Last for Best: A Positivity Bias for End Experiences. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Oishi, S. End Effects of Rated Life Quality: The James Dean Effect. Psychol. Sci. 2001, 12, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Yielding to Temptation: Self-Control Failure, Impulsive Purchasing, and Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 28, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking Time Seriously: A Theory of Socioemotional Selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. In Interpersonal Development; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 57–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, T.C.T.; Lee, Y. “I Want to Be as Trendy as Influencers”–How “Fear of Missing out” Leads to Buying Intention for Products Endorsed by Social Media Influencers. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 346–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, N.; Nowlis, S.M. The Effect of Making a Prediction about the Outcome of a Consumption Experience on the Enjoyment of That Experience. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; David, M.E. The Social Media Party: Fear of Missing Out (FoMO), Social Media Intensity, Connection, and Well-Being. Int. J. Hum.—Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudry, E.; Vagg, P.; Spielberger, C.D. Validation of the State-Trait Distinction in Anxiety Research. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1975, 10, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesler, C. COVID-19 Lockdown Nostalgia: It Was a Scary Time, but I Will Miss Our Enforced Family Togetherness—The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/COVID-19-put-me-and-my-family-in-lockdown-im-feeling-weirdly-nostalgic-now-that-its-lifted/2020/07/24/bb07d068-c156-11ea-9fdd-b7ac6b051dc8_story.html (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Baumeister, R.F.; Heatherton, T.F. Self-Regulation Failure: An Overview. Psychol. Inq. 1996, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Gender Differences in Erotic Plasticity: The Female Sex Drive as Socially Flexible and Responsive. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisman, A.; Koole, S.L. Hiding in the Crowd: Can Mortality Salience Promote Affiliation with Others Who Oppose One’s Worldviews? J. Per. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Jiang, X.; Fan, X. How Social Media’s Cause-Related Marketing Activity Enhances Consumer Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Community Identification. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Ha, S. Examining Identity-and Bond-Based Hashtag Community Identification: The Moderating Role of Self-Brand Connections. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Wang, W.; Du, P.; Filieri, R. Impact of Brand Community Supportive Climates on Consumer-to-Consumer Helping Behavior. JRIM 2023, 17, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Kozinets, R.V.; Sherry, J.F. Teaching Old Brands New Tricks: Retro Branding and the Revival of Brand Meaning. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Kelly, K.M.; Cottrell, C.A.; Schreindorfer, L.S. Construct Validity of the Need to Belong Scale: Mapping the Nomological Network. J. Per. Assess. 2013, 95, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Perkins, A.; Sprott, D. The Effect of Start/End Temporal Landmarks on Consumers’ Visual Attention and Judgments. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Jiang, Y. Examining Consumer Affective Goal Pursuit in Services: When Affect Directly Influences Satisfaction and When It Does Not. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 1177–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, P.K.; Kulkarni, G. The Impact of COVID-19 on Customer Journeys: Implications for Interactive Marketing. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N. Post-Pandemic Marketing: When the Peripheral Becomes the Core. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C. Augmenting Brand Community Identification for Inactive Users: A Uses and Gratification Perspective. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, E.; Porter, M., III; Anaza, N.A.; Min, D.-J. The Impact of Storytelling in Creating Firm and Customer Connections in Online Environments. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C.; Wildschut, T. Nostalgia across Cultures. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2022, 16, 18344909221091649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Santini, F.O.; Lim, W.M.; Ladeira, W.J.; Costa Pinto, D.; Herter, M.M.; Rasul, T. A Meta-Analysis on the Psychological and Behavioral Consequences of Nostalgia: The Moderating Roles of Nostalgia Activators, Culture, and Individual Characteristics. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 1899–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, S.; Tian, M.; Fan, Q.; Zhang, Y. Temporal Landmarks and Nostalgic Consumption: The Role of the Need to Belong. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020123

Song S, Tian M, Fan Q, Zhang Y. Temporal Landmarks and Nostalgic Consumption: The Role of the Need to Belong. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(2):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020123

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Sigen, Min Tian, Qingji Fan, and Yi Zhang. 2024. "Temporal Landmarks and Nostalgic Consumption: The Role of the Need to Belong" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 2: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020123

APA StyleSong, S., Tian, M., Fan, Q., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Temporal Landmarks and Nostalgic Consumption: The Role of the Need to Belong. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020123