A Qualitative Exploration of Postoperative Bariatric Patients’ Psychosocial Support for Long-Term Weight Loss and Psychological Wellbeing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

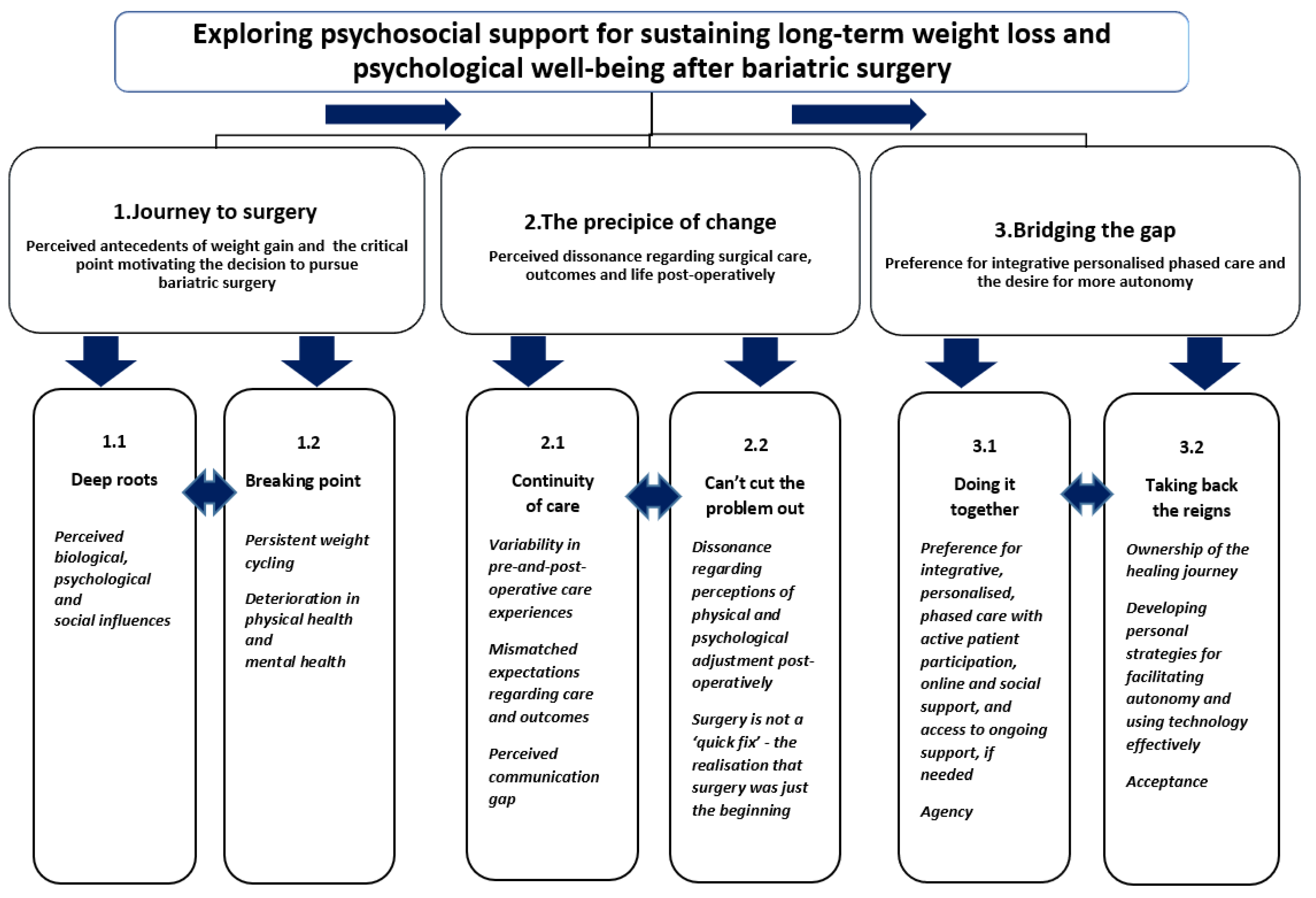

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1—Journey to Surgery

P15: “It’s genetic, we are programmed to like sweet things… my grandmother was diabetic. My mom’s sisters were all diabetic as well. We were all overeaters … we just thought you’re fat because your parents were fat.”

P13: “She had a bad relationship with food she projected onto me… my mom put me down quite a lot… Parents have a big role to play.”

P4: “People have lost the skill of how to cook … years ago, mums used to make sure kids could cook before they left home… But the skills are not being passed down… Mums and dads get ready-meals as meals.”

P15: “My journey started in childhood… a generation where you clear your plate… Often food is connected to nurture and love… I’m feeling down or treat myself… So, it’s all of our conditioning…”

P6: “I think we are getting used to having a more sedentary lifestyle… eating fast food… people don’t want to be obese but also don’t want to spend a huge amount of money on gyms. It’s not practical… Sometimes it’s about lack of opportunity… time… and it’s about lack of resources. It can be expensive… ”

P11: “I was very overweight and very uncomfortable. I tried all the weight loss… things just got out of control… Then there was this surgery… it was what I needed.”

P1: “I was on blood pressure meds… a few of them made me really sick … I walked into the minefield of Type 2 diabetes… That was the thing that tipped me over the edge to take some action.”

P9: “If it continues like this, I am going to be dead.”

3.2. Theme 2—The Precipice of Change

P15: “…the NHS… are very rigid… ‘one size fits all.’ And it doesn’t!”

P4: “I had it on the NHS, which I am grateful for because I wouldn’t have been able to afford it… I think the NHS programme works because there is support there.”

P12: “Nurses and surgeons were great… I could not fault them… I had a fantastic dietitian.”

P1: “My care was tidy and was part and parcel of a package… a pre-package, the surgery itself with the care I needed after… for 12 months… I had access to a superb group of staff… I wasn’t cut adrift… ”

P10: “I had a year support package… from the company that I had the surgery with… they phoned me every few weeks, and then it tailed off, and then after a year there was nothing… I would have had to pay more for support after a year.”

P14: “No support, because it was a private… before the surgery, there was no proper… explanations... Now, I’m going through the NHS… the doctor’s really supporting…”

P15: “…after surgery you really were on your own… all they were interested in was the weight loss… the numbers on the scales…”

P9: “They’re incompetent… and the very bad aftercare… it makes it quite negative in your brain… But then there’s this promise that you’re going to be slim. So… you’re willing to put up with crap… if your ultimate dream is going to come true.”

P6: “I did pretty well in the first year to 18 months. It was 2 years out when I’ve had the problems…They passed me back to my GP… I think GP practices aren’t set up to do post-surgery with people like us… More needs to be done to educate GP surgeries… on bariatric needs.”

P14: “…I just had 2 years… but afterwards, when the problem starts, then your packages stops…”

P6: “…there is so much misunderstood about bariatric surgery... I think people just see it as a solution... It doesn’t fix the problem… or what comes out of the surgical process…”

P8: “…it didn’t cure my emotional eating… I was skinnier, but I was still the same person…”

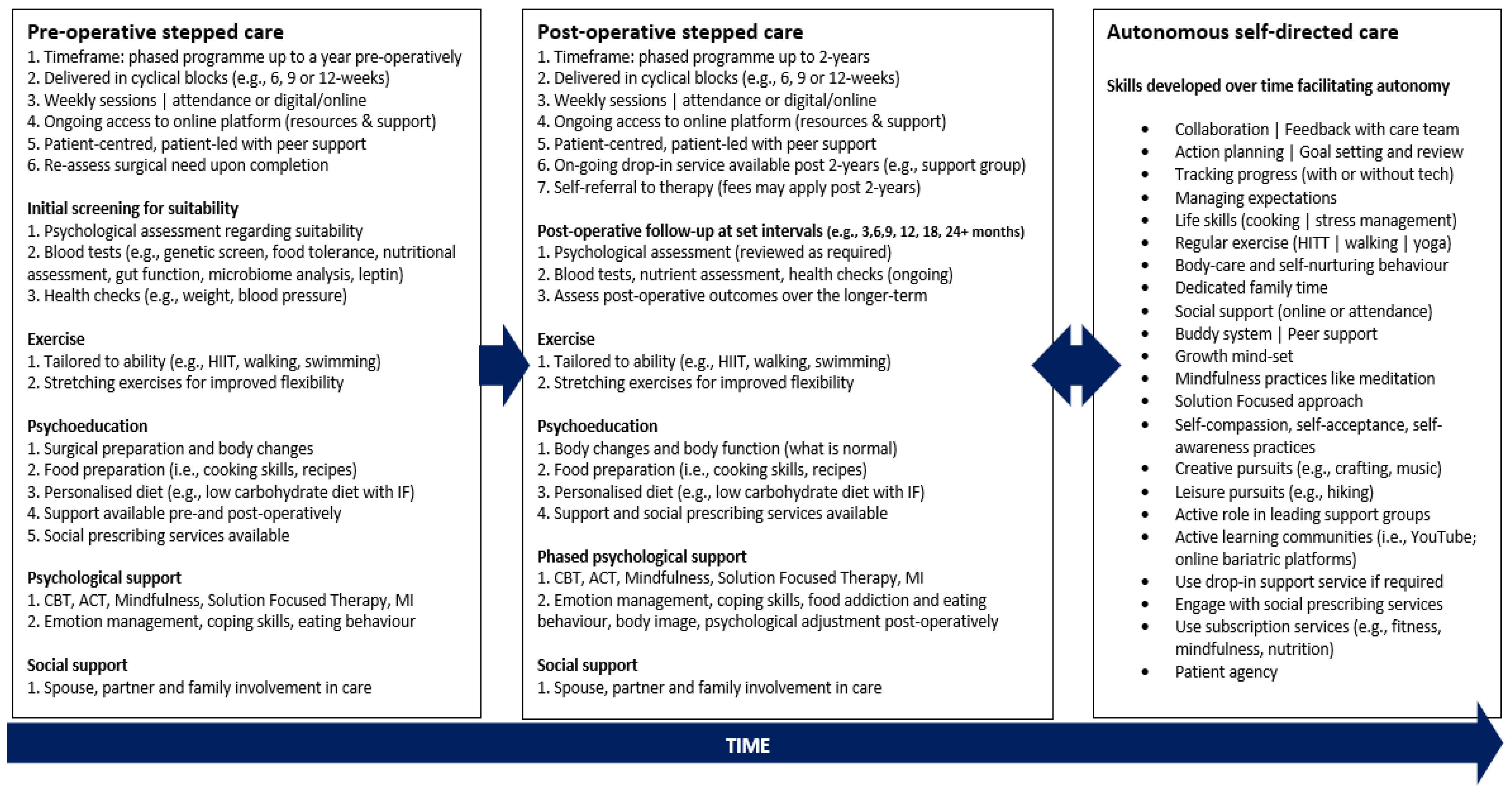

3.3. Theme 3—Bridging the Gap

P2: “Psychological support before and after around body image and changing your mindset. Ongoing nutritional support… including exercise… education around understanding your body and the changes after surgery… even if you paid for it and then tapped into it when you needed… support specifically for people who have had bariatric surgery.”

P2: “It’s around the food, meal planning… the hormones… understanding my genes… why I make certain food choices…”

P6: “… genetic testing, microbiome analysis to help me understand my body…”

P9: “Exploring personalised nutrition… to suit individual needs…”

P4: “Ideal package to me is one of support… life skills, mental skills… actually implementing it into your life… Buddy system, pre-op prep and post-op prep to include counselling and life skills.”

P8: “…you need to prepare people for what is going to happen… they need a lot of aftercare… psychologically… you need structured support up to 2 years because that’s when most of the change is happening, and then dip in sessions afterwards…”

P1: “… human contact is the key! I had this whole network of support… my wife, my kids. People around me… kept me positive and motivated… It’s getting support from your community…”

P15: “A programme just for an hour to two hours a week, evening class… nutrition, operation side-effects, psychological aftercare… Maybe 4 weeks before and then have 8 weeks after or even longer so people could have their dropping-in sessions... Have a guest speaker… an online platform where you did a one-or-two-hour Zoom class… no more than ten people... Have your discussions, Q and A… Exercise as part of a module… A physiotherapist could maybe advise on a programme…”

P2: “A combination of dip-in and ongoing support… ‘touch points’ where you contact this person and monitor yourself… maybe post 2 years… I know it’s the NHS, but they should have something in place… for those who need further support… Even if we had to pay for it.”

P6: “… follow up… at 3, 6, 9, 12 months… a bit more support people were offered it… something ongoing… I’m not saying the NHS should solve everybody’s problems… But I’m saying there’s a little bit it can do to help with a long-term solution… I’m three years out, my life’s changing all the time. What I need now, is different to what I needed three years ago! So being able to go back and have an annual review with somebody, to check whether I’m on track, have a support network, I can tap into…”

P4: “You have to own the journey.”

P3: “You need to change your mindset… why are you doing it? You are responsible for yourself! …you can’t always get the help that you need… You’ve got to find it yourself.”

P7: “I’m worried about my health, and I don’t want to go back on prescription medication!... I’m going to be dedicated for the next 10 years because I want to be sticking to a healthy lifestyle… I’m quite pleased about my journey… I’ve been the driver, nobody else!”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

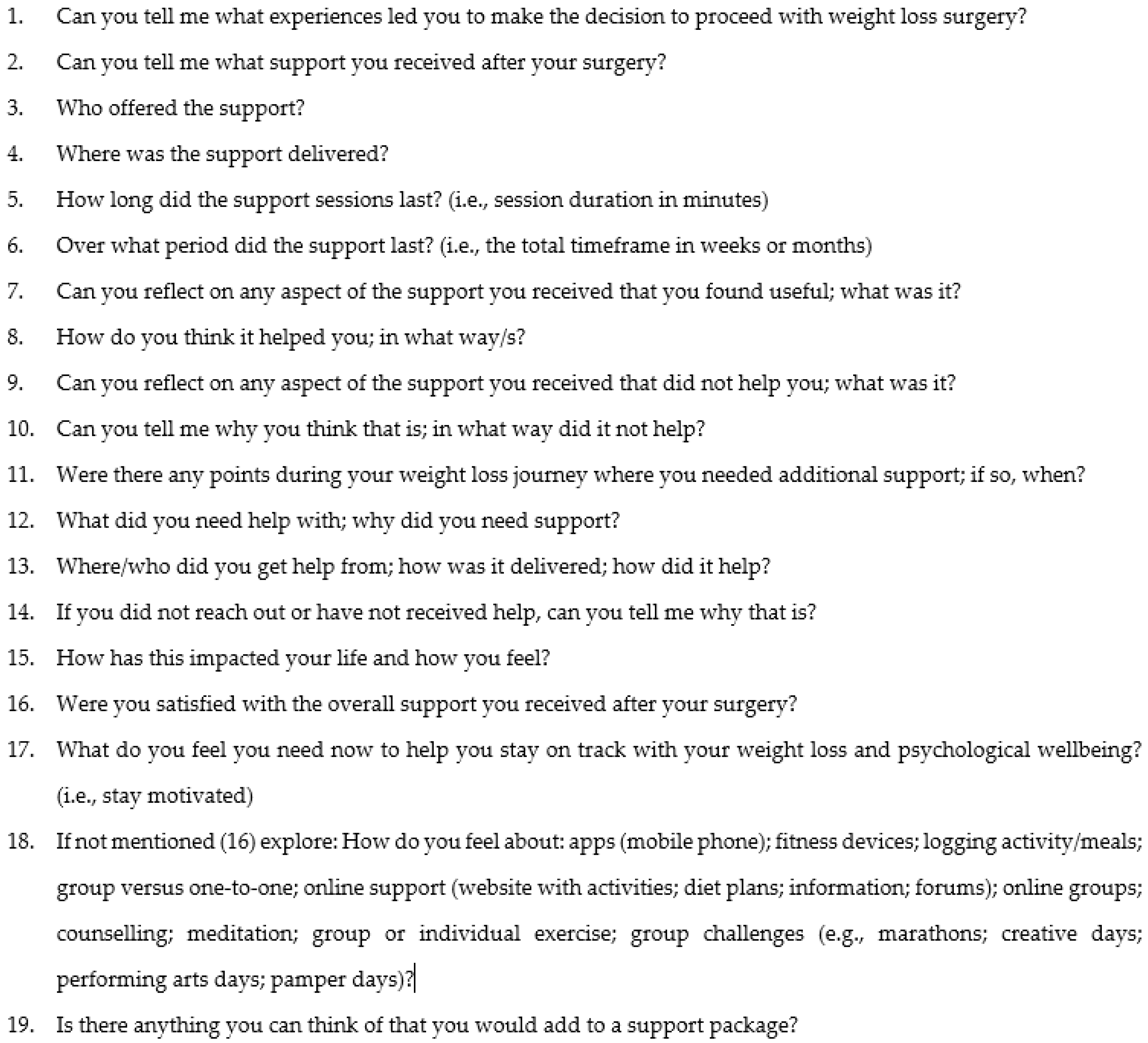

Appendix A

- Are you happy to proceed?

- Do you have any questions?

| 1. Gender | |

| 2. Age | |

| 3. Occupation | |

| 4. Ethnicity | |

| 5. Town/City | |

| 6. Overall health and wellbeing | Before surgery: Current: |

| 7. Length of time postoperative | |

| 8. Pre-surgery weight | |

| 9. Current weight | |

| 10. Length of time spent at current weight |

- Can you tell me what experiences led you to make the decision to proceed with weight loss surgery?

- Can you tell me what support you received after your surgery?

- Who offered the support?

- Where was the support delivered?

- How long did the support sessions last? (i.e., session duration in minutes)

- Over what period did the support last? (i.e., the total timeframe in weeks or months)

- Can you reflect on any aspect of the support you received that you found useful; what was it?

- How do you think it helped you; in what way/s?

- Can you reflect on any aspect of the support you received that did not help you; what was it?

- Can you tell me why you think that is; in what way did it not help?

- Were there any points during your weight loss journey where you needed additional support; if so, when?

- What did you need help with; why did you need support?

- Where/who did you get help from; how was it delivered; how did it help?

- If you did not reach out or have not received help, can you tell me why that is?

- How has this impacted your life and how you feel?

- Were you satisfied with the overall support you received after your surgery?

- What do you feel you need now to help you stay on track with your weight loss and psychological wellbeing? (i.e., stay motivated)

- If not mentioned in (16), explore: How do you feel about: apps (mobile phone); fitness devices; logging activity/meals; group versus one-to-one; online support (website with activities; diet plans; information; forums); online groups; counselling; meditation; group or individual exercise; group challenges (e.g., marathons; creative days; performing arts days; pamper days)?

- Is there anything you can think of that you would add to a support package?

- Thank you for your participation.

- The debriefing document will be sent to you via e-mail.

References

- Taylor, M.M. The globesity epidemic. In The Obesity Epidemic; Palgrave Pivot: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pozza, C.; Isidori, A.M. What’s behind the obesity epidemic? In Imaging in Bariatric Surgery; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nicklas, T.A.; O’Neil, C.E. Prevalence of obesity: A public health problem poorly understood. AIMS Public Health 2014, 1, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, D.M. Biopsychosocial Modifiers of Obesity. In Bariatric Endocrinology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 325–359. [Google Scholar]

- Holovatyk, A. Toward a Biopsychosocial Model of Obesity: Can Psychological Well-Being Be the Bridge to Integration? Ph.D. Thesis, Nova South Eastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. 2020. Available online: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 27 September 2020).

- Van Zyl, N.; Andrews, L.; Williamson, H.; Meyrick, J. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions to support psychological well-being in post-operative bariatric patients: A systematic review of evidence. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, S.A.; Yeh, G.Y.; Davis, R.B.; Wee, C.C. A mindfulness-based intervention to control weight after bariatric surgery: Preliminary results from a randomized controlled pilot trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2016, 28, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumbe, S.; Hamlet, C.; Meyrick, J. Psychological aspects of bariatric surgery as a treatment for obesity. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leahey, T.M.; Bond, D.S.; Irwin, S.R.; Crowther, J.H.; Wing, R.R. When is the best time to deliver behavioral intervention to bariatric surgery patients: Before or after surgery? Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2009, 5, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.K.; King, M.; Vartanian, L.R. Patient perspectives on psychological care after bariatric surgery: A qualitative study. Clin. Obes. 2020, 10, e12399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, B.J.; David, D.M.; Gruber, J.A. Rethinking the biopsychosocial model of health: Understanding health as a dynamic system. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2017, 11, e12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe, D.E.; Ramsden, V.R.; Banner, D.; Graham, I.D. Using qualitative health research methods to improve patient and public involvement and engagement in research. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2018, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, G.M.; Hammond, S.E.; Fife-Schaw, C.E.; Smith, J.A. Research Methods in Psychology; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Willig, C. Introducing Qualitative Research in Psychology; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Deakin, H.; Wakefield, K. Skype interviewing: Reflections of two PhD researchers. Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The British Psychological Society. Code of Human Research Ethics. Leicester: The British Psychological Society. 2014. Available online: https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/bps.org.uk/files/Policy/Policy%20-%20Files/BPS%20Code%20of%20Human%20Research%20Ethics.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- The British Psychological Society. Ethics Guidelines for Internet-Mediated Research. Leicester: The British Psychological Society. 2013. Available online: https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/bps.org.uk/files/Policy/Policy%20-%20Files/Ethics%20Guidelines%20for%20Internet-Mediated%20Research%20%282013%29.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Small, P.; Mahawar, K.; Walton, P.; Kinsman, R. The National Bariatric Surgery Registry Report, 3rd ed.; Dendrite Clinical Systems: Reading, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Youdim, A.; Jones, D.B.; Garvey, W.T.; Hurley, D.L.; McMahon, M.M.; Heinberg, L.J.; Kushner, R.; Adams, T.D.; Shikora, S.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient—2013 Update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Obesity 2013, 21, S1–S27. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, B.; Hünnemeyer, K.; Sauer, H.; Schellberg, D.; Müller-Stich, B.P.; Königsrainer, A.; Weiner, R.; Zipfel, S.; Herzog, W.; Teufel, M. Sustained effects of a psychoeducational group intervention following bariatric surgery: Follow-up of the randomized controlled BaSE study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 13, 1612–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomss.org.uk. NBSR|BOMSS. Available online: https://www.bomss.org.uk/nbsr/ (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Kelemen, M.; Rumens, N. Pragmatism and heterodoxy in organization research: Going beyond the quantitative/qualitative divide. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2012, 20, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Edhlund, B.; McDougall, A. Nvivo Essentials. 2019. Available online: https://search.worldcat.org/title/1086332947 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Engel, G.L. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. In The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy: A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1981; Volume 6, pp. 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 22, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugiavini, A.; Buia, R.E.; Kovacic, M.; Orso, C.E. Adverse childhood experiences and unhealthy lifestyles later in life: Evidence from SHARE countries. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2022, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymowitz, G.; Salwen, J.; Salis, K.L. A mediational model of obesity-related disordered eating: The roles of childhood emotional abuse and self-perception. Eat. Behav. 2017, 26, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loos, R.J.; Yeo, G.S. The genetics of obesity: From discovery to biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaegen, A.A.; Van Gaal, L.F. Drug-induced obesity and its metabolic consequences: A review with a focus on mechanisms and possible therapeutic options. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2017, 40, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, A.; Townshend, T. Obesogenic environments: Exploring the built and food environments. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2006, 126, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, M.; Buckland, N.; Blundell, J. Psychobiology of Obesity: Eating Behavior and Appetite Control. In Clinical Obesity in Adults and Children; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Puhl, R.M.; Himmelstein, M.S.; Pearl, R.L. Weight stigma as a psychosocial contributor to obesity. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flint, S.W.; Čadek, M.; Codreanu, S.C.; Ivić, V.; Zomer, C.; Gomoiu, A. Obesity discrimination in the recruitment process: “You’re not hired!”. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Luedicke, J. Weight-based victimization among adolescents in the school setting: Emotional reactions and coping behaviors. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasardo, A.E.; McHugh, M.C. From fat shaming to size acceptance: Challenging the medical management of fat women. In The Wrong Prescription for Women: How Medicine and Media Create a “Need” for Treatments, Drugs, and Surgery; Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, E.; Haynes, A.; Sutin, A.; Daly, M. Self-perception of overweight and obesity: A review of mental and physical health outcomes. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2020, 6, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latner, J.D.; Puhl, R.M.; Murakami, J.M.; O’Brien, K.S. Food addiction as a causal model of obesity. Effects on stigma, blame, and perceived psychopathology. Appetite 2014, 77, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, A.M.; Quigley, K.M.; Wadden, T.A. The Behavioral Treatment of Obesity. In Clinical Obesity in Adults and Children; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Perriard-Abdoh, S.; Chadwick, P.; Chater, A.M.; Chisolm, A.; Doyle, J.; Gillison, F.B.; Greaves, C.; Liardet, J.; Llewellyn, C.; McKenna, I.; et al. Psychological Perspectives on Obesity: Addressing Policy, Practice and Research Priorities; British Psychological Society: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Spirou, D.; Raman, J.; Bishay, R.H.; Ahlenstiel, G.; Smith, E. Childhood trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, early maladaptive schemas, and schema modes: A comparison of individuals with obesity and normal weight controls. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, J.P.S.; Martinino, A.; Manicone, F.; Pereira, M.L.S.; Puzas, Á.I.; Pouwels, S.; Martínez, J.M. Bariatric surgery on social media: A cross-sectional study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 16, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvholm, K.; Olbers, T.; Engström, M. Patients’ views of long-term results of bariatric surgery for super-obesity: Sustained effects, but continuing struggles. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2021, 17, 1152–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geerts, M.M.; van den Berg, E.M.; van Riel, L.; Peen, J.; Goudriaan, A.E.; Dekker, J.J. Behavioral and psychological factors associated with suboptimal weight loss in post-bariatric surgery patients. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2021, 26, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, I.; Raman, J.; Sui, Z. Patient motivations and expectations prior to bariatric surgery: A qualitative systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1608–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitzsch, A.; Schweda, A.; Hetkamp, M.; Niedergethmann, M.; Dörrie, N.; Herpertz, S.; Hasenberg, T.; Tagay, S.; Teufel, M.; Skoda, E.M. The impact of psychological resources on body mass index in obesity surgery candidates. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, N. An Exploratory Qualitative Study with Post-Operative Bariatric Patients around the Psychosocial Support Required for Sustaining Long-Term Weight Loss and Psychological Well-being (Doctoral Dissertation, University of the West of England). 2022. Available online: https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/7864613 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

| Participant | Gender | Age | Occupation | Ethnicity | Location | Surgery provider | Pre-op health | Post-op health | Duration post-op | Pre-op weight | Current weight | Maintained weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | M | 57 | Sales Manager & Enabler | Asian British | Peterborough Cambridgeshire | Gastric sleeve PRIVATE | T2DM; hypertension; chronic pain; meds | No meds; conditions resolved | 5yr2014 | 25st | 15st 5 | 4yr |

| P2 | F | 52 | Employment adviser | Black British | Hackney London | Gastric bypass NHS | T2DM; poor health; meds | No meds; conditions resolved | 3yrs2016 | 16st | 14st | 3mos |

| P3 | F | 54 | Practice nurse | Black British | Hackney London | Gastric sleeve NHS | T2DM; hypertension; meds | No meds; conditions resolved | 4yrs2015 | 16st 2 | 12st | 1yr |

| P4 | F | 40 | Senior support worker | White British | Folkestone Kent | Gastric band NHS | Well and active; no meds; fertility concerns | Weight loss | 2yr2017 | 16st 5 | 13st 2 | 4mos |

| P5 | F | 44 | Cleaner & Health care assistant | White British | Bath Gloucestershire | Gastric bypass NHS | Anxiety, depression (long-term); T2DM; PCOS; asthma; sleep apnoea | T2DM and sleep apnoea resolved; anxiety, depression and asthma managed with medication | 5yr 2015 | 18st 7 | 11st | 1yr |

| P6 | F | 49 | MSc Student & Risk and compliance consultant | White British | Clevedon Somerset | Gastric band (failed) PRIVATE Gastric bypass PRIVATE | Fair health; reflux and digestive problems | Good health; conditions resolved | 4yr post-bypass2016Band (2008) removed 2014 | 24st 4 | 16st | 6-8mos |

| P7 | M | 45 | Driver | White British | Twickenham London | Gastric sleeve PRIVATE | Poor health; chronic pain; hypertension; insomnia; high cholesterol; depression; anxiety; meds | Conditions resolved; no meds; improved mental health | 2yr2017 | 26st 7 | 15st 7 | 1yr |

| P8 | F | 33 | Nurse | White British | Cookstown Northern Ireland | Mini-bypass PRIVATE | Depression, anxiety and PTSD; emotional eating | Improved health initially, then decline in mental health | 2yr2017 | 24st | 13st | 6mos |

| P9 | F | 48 | Hypno-therapist | White British | Trowbridge Wiltshire | Gastric band NHS | Poor health; unfit; T1DM | Improved health initially then declined with weight regain; TD1M challenges | 10yr2010 | 25st 5 | 26st 5 | 1wkVariable weight |

| P10 | F | 40 | Self-employed & retail manager & carer | White British | Bury St. Edmonds Suffolk | Gastric bypass PRIVATE | Fair health; low self-esteem; depression; anxiety; mobility issues | Improved health and mobility; loose skin; low mood; anxiety; adjustment challenges; congenital health defect diagnosed | 10yr2010 | 21st | 13st | 2yr |

| P11 | F | 36 | Nurse | White British | Hampton Surrey | Gastric bypass NHS | Fair health; emotional eating; mobility issues | Improved health and mobility; adjustment challenges; dumping syndrome | 9yr2011 | 23st | 17st | 2yr |

| P12 | F | 53 | Housewife | White British | Knottingley Yorkshire | Gastric bypass NHS | Poor health; mobility issues; pain; breast cancer; meds | Improved health and mobility; lung AVN 2015; currently in good health; no meds | 11yr2009 | 21st 10 | 10st 2 | 7yr |

| P13 | F | 56 | University administrator | White British | Bristol Gloucestershire | Gastric band NHS | Poor health; T2DM; high cholesterol; hypertension; meds | Conditions improved; controlled with meds; T2DM challenges | 12yr2008 | 25st 9 | 16st 2 | 6mosVariable weight |

| P14 | F | 44 | Self-employed | Lithuanian/ White British | Walthamstow London | Gastric band PRIVATE | Fair health; depressed; poor mobility | Initially improved health, mood and mobility; then health deteriorated with band complications. Band will be removed; back in Tier 3 for bypass | 7yr2013 | 18st 9 | 15st 6 | 1moVariable weight |

| P15 | F | 52 | Counsellor Educator | White British | Kingston Surrey | Gastric bypass NHS | Poor health; T2DM; mobility issues; depression; meds | Improved health and mobility; improved mood; no meds | 8yr2012 | 22st | 17st | 1mo Variable weight3-year plateau |

| Sample Size | n = 15 |

|---|---|

| Age | Mage 47 years |

| Gender | n = 13 (87%) Female n = 2 (13%) Male |

| Ethnicity | n = 1 (7%) Asian British n = 2 (13%) Black British n = 12 (80%) White British |

| Occupation | n = 2 (13%) Self-employed n = 1 (7%) Unemployed n = 12 (80%) Employed |

| Procedure | n = 8 (53%) Gastric bypass n = 3 (20%) Sleeve gastrectomy n = 4 (27%) Gastric band |

| Average time postoperative | 6 years |

| Remission of comorbidities observed at 1-year follow-up | n = 9 (60%) |

| Poor physical and psychological outcomes | n = 6 (40%) |

| Provider | n = 9 (60%) NHS n = 6 (40%) Private |

| Themes and Sub-Themes | Description and Quotes |

|---|---|

| 1. Journey to surgery | Perceived antecedents of weight gain and the critical point motivating the decision to pursue bariatric surgery |

| 1.1 Deep roots | Explores participants’ views regarding the cause of their problem with obesity, which includes the impact of biological (e.g., heredity, health), psychological (e.g., experiences of trauma, maladaptive coping styles), and social influences (e.g., socialisation, the obesogenic environment, dietary information, socio-economic status) |

| P15: “We were all overeaters as well and or diabetic… I do remember all my childhood being bullied because I was the fat kid. My mother was quite cruel as well and would say things… There were no boundaries at home... scoff what’s in the cupboard and then have dinner… Then you’d be then criticised for being so fat, but there was no knowledge to help, no support. No education to not do it. We just didn’t know.” P6: “My mum suffered from anorexia when I was a child. My parents had a very unhappy marriage. I didn’t look at how it changed my relationship with food… So, it was comfort food, and so food just became a solace for both the ups and the downs, and that has just carried on throughout life.” P1: “Often, in the Asian community… weight is a sign of affluence! … you’re raised to clean your plate. You must not waste food.” | |

| 1.2 Breaking point | Explores participants’ perceptions regarding the impact of persistent weight cycling and its contribution to the deterioration of physical and mental health, motivating their decision to pursue bariatric surgery |

| P10: “I didn’t want judgment… mentally. It was the only place I had left to go. I couldn’t control it physically.” P4: “I got married and then wanted to have children… My BMI was too high… so they wouldn’t even touch me for any fertility tests.” P5: “For my health. I didn’t really have much choice. It was basically like if you don’t get it done in 5 years, you’ll be dead.” P8: “I did it more workwise because I was 24 stone, and I’m not going to be able to carry out CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) on patients or anything… I just reached breaking point, where I was just so unhappy. I was suffering from chronic PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) from early childhood traumas and teenage traumas. I have very low self-esteem issues.” | |

| 2. The precipice of change | Perceived dissonance regarding surgical care, outcomes, and life postoperatively |

| 2.1 Continuity of care | Explores the variability in participant experiences pre and postoperatively (e.g., mismatched expectations regarding care and outcomes, perceived communication gap) |

| P12: “No psychological support whatsoever. I had a fantastic dietitian. I went to see her fortnightly to start with, and then it went to monthly, then 3-monthly, and then after I’d hit my target weight, they discharged me, and that was it.” P13: “They make you go in and speak to a psychologist because they have to make sure you are mentally well enough to have one. I passed all the tests, and then I had the band. I was discharged. I went back a couple of times to have the band filled a bit more… I didn’t see anybody else… I got leaflets… very basic information.” P9: “I saw the very obnoxious surgeon, and he explained about gastric bands, gastric bypass and told me that when I had a gastric bypass, all my insulin would start rushing in… but I don’t have insulin. I have Type 1 diabetes... How is that going to work? And he went, ‘Don’t be ridiculous you have Type 2 diabetes!’ So right from the start, I was argued with… over what type diabetes I had.” | |

| 2.2 Can’t cut the problem out | Explores the perceived dissonance participants experienced regarding their physical and psychological adjustment to life postoperatively |

| P7: “I think what’s not made clear to you is the downsides of bariatric surgery. It’s very much pushed as an amazing thing, which it is, but there are downsides to it.” P15: “… it is really hard to adjust mentally. I think it was a lot worse than what I thought it would be. I thought, great, I’m gonna be thin, and it is not as simple as that. It really isn’t.” P5: “The coping and adjustment to a new body is a big thing.” P1: “Well, I didn’t enjoy food after surgery. It is the hardest thing to come to terms with, particularly when you’re used to richer diets… that was a mental hurdle I had to overcome.” P11: “I get the dumping syndrome… feel ill, sick… My bowels open easily. It can be a problem when I work because I’m out… doing home visits as a community nurse. But I’m always around a toilet.” | |

| 3. Bridging the gap | Preference for integrative personalised phased care and the desire for more autonomy |

| 3.1 Doing it together | Explores participants’ views and preferences regarding what components would make an ideal support package (e.g., integrative personalised phased care, active patient participation, online and social support, ongoing access to support, agency) |

| P2: “It’s around the weight gain, and it’s around the food, meal planning, understanding my body, the hormones, even understanding my genes, like why I make certain food choices… psychological support before and after around body image and changing your mindset. Ongoing nutritional support… a bit of everything, including exercise. Also, some education around understanding your body changes after surgery… The nutrition support would be specifically for people who have had bariatric surgery.” P12: “… have an open-door policy; if you’re struggling, you can get back in touch… even if it’s every 3 months… more patient-led…” P9: “I would put in the latest research on dietary advice because I think with that, possibly, the need for surgery would go away for quite a lot of patients… and then to support those after surgery.” P1: “It’s getting support from your community, your family, from all sources, from work colleagues…” P6: “Potentially, the blood tests around the targeted dieting, etc., rather than just follow a healthier diet… Genetic testing and microbiome analysis to help me understand my body… why I gain weight at 1500 calories… It would help address my guilt… perhaps even my sense of self-blame.” | |

| 3.2 Taking back the reigns | Explores participants’ experiences and perceptions regarding their personal journey towards autonomy (e.g., ownership, mindset, skill development, self-regulation strategies, effective use of technology, self-care practices, self-acceptance) |

| P5: “I’ve got my own counsellor, which I pay for privately.” P4: “You have to own the journey… I’m always organised… I do a fortnightly meal plan… I make certain meals, more than I need, and then I put them in the freezer. We don’t eat convenience food, I like to cook from scratch.” P8: “Self-acceptance is a big thing… I do fast now because that works with mindfulness. I realised that it was head hunger, whereas before, I wasn’t aware that it was head hunger.” P3: “You need to do your research. It’s something you need to know because the food that you love, you won’t be able to eat it anymore. What is going to be your main support?” P9: “I have an exercise video that is aimed at people who are very obese… I am a member of keto groups, low-carb groups, keto for Type 1 diabetics, and intermittent fasting.” P2: “At work, we were doing a step challenge in September that was good because then you use your app more because you have a group of people that you’re training with.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Zyl, N.; Lusher, J.; Meyrick, J. A Qualitative Exploration of Postoperative Bariatric Patients’ Psychosocial Support for Long-Term Weight Loss and Psychological Wellbeing. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020122

Van Zyl N, Lusher J, Meyrick J. A Qualitative Exploration of Postoperative Bariatric Patients’ Psychosocial Support for Long-Term Weight Loss and Psychological Wellbeing. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(2):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020122

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Zyl, Natascha, Joanne Lusher, and Jane Meyrick. 2024. "A Qualitative Exploration of Postoperative Bariatric Patients’ Psychosocial Support for Long-Term Weight Loss and Psychological Wellbeing" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 2: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020122

APA StyleVan Zyl, N., Lusher, J., & Meyrick, J. (2024). A Qualitative Exploration of Postoperative Bariatric Patients’ Psychosocial Support for Long-Term Weight Loss and Psychological Wellbeing. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020122