Appendix A. Case Study—Using the DMM and the APCI

Using the DMM as a tool, the following case study describes a Screening Family Formulation (SFF) [

1] and an Assessment of Parent–Child Interaction (APCI). The main aim of the SFF is to understand the functions of the behaviors of the family in relation to safety and comfort. The SFF assumes that behavior functions to keep people safe and that, as a strengths-based model, this behavior has been the right thing to do in certain contexts. Therapists leading the work with the family will take this understanding and use it to gently change the way individuals process information of threat so that safety and comfort can be sought when needed. Practically, the SFF contains ten tasks which look at the family holistically, with thought given to the levels of safety each family member feels and needs. The assessing therapist is asked to make a statement on intimacy, for example, in a concise manner. Then, using knowledge gained from the DMM model, the therapist writes a conclusion based on the information gained so far, and suggests questions to further understand the family’s motivations and strategies.

Following the SFF, an APCI was undertaken with the family with the aims of providing quantitative and qualitive information attachment styles and parenting capacity in the family. The APCI, once described by a trainee as “Truthful Kindness”, highlights the positives and challenges of the family through musical metaphor. Using four activities on non-verbal communication, mutual attunement and the emotional parental responses, the assessing therapist can understand patterns of interaction in the family. Therapists are trained to notice the difficulties that are presented in the family and what is working well so that families start their therapeutic journey in way that promotes confidence within the individuals. Both the SFF and the APCI hold hope for the family at the center of the assessments.

Meeting the Family: The following case study has been anonymized, although consent was given by the family to take part in the assessment, supervision, and sharing of information for this article.

Brief History: Joanna, 15, was referred for a specialist assessment by her adoptive parents. Joanna had been removed from her birth mother at birth, to a safe foster home. She remained there until she was 18 months old when she went to live with Mr. and Mrs. Townsend. In later childhood, Joanna had been assessed for ADHD and ASD, with a slightly raised score on ADHD only.

Problem at Referral: Joanna had recently taken an overdose and her parents did not understand why this had happened. Through gentle questioning by the therapist, Mrs. Townsend revealed that Joanna had been in contact with her birth family, and this had brought on some behavioural changes, including the onset of ‘fits’ (physical shaking) and self-harm. Joanna had also started to have questions about her gender and identity.

Planned Intervention: To support the family, an APCI was undertaken alongside an SFF. The SFF was undertaken with supervision by an expert in the field as part of a certification program. The SFF described here is abridged for the purposes of this article.

Intervention Narrative: In the initial referral, Mr. and Mrs. Townsend stated that they did not understand why Joanna had become distressed. However, as the exploration of the case progressed, there were many indicators of Joanna’s distress that her parents had not been able to acknowledge. Joanna seemed unable to say her feelings out loud (to her parents or another person) and she was showing those around her those emotions through self-harm. Joanna had also been hiding personal items away from her parents and this could be an indicator of her having shame around her own needs and more negative feelings [

1]. In contrast to Joanna’s outward self-harm and overdose, her parents were worried about what other people would think about their family and they were inhibiting negative feelings by focusing on ‘doing’ or behavioural issues with Joanna. In line the DMM model, the assessing therapist used questions around danger and safety to further understand the strategies of the family:

where was the danger at this point and what was making Joanna feel unsafe in the here and now?

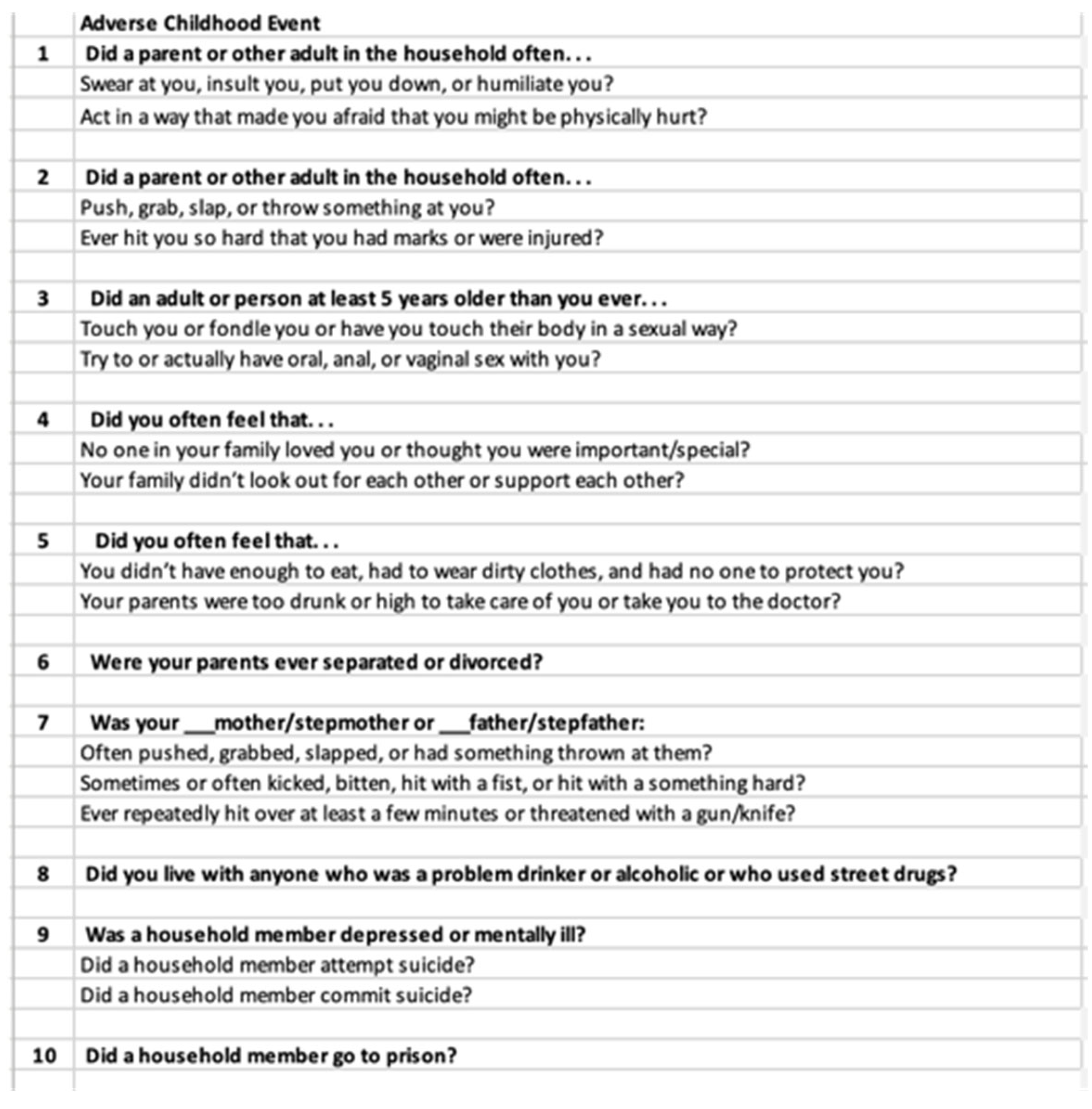

Mr. and Mrs. Townsend were asked to complete an Adverse Childhood Event checklist (See

Figure A1). Mr. Townsend stated a small incident as a child and Mrs. Townsend, who completed the form, said that she had had no negative experiences as a child and neither had Joanna. The average score for the general population is approximately five adverse experiences. Given that the family had stated such a low score, the assessing therapist felt that this concurred with the inhibited negative affects stated above. The questions from the early part of the work, around “

where is the danger?”, remained in place when thinking about the family.

Figure A1.

Adverse Childhood Events for the Townsend Family.

Figure A1.

Adverse Childhood Events for the Townsend Family.

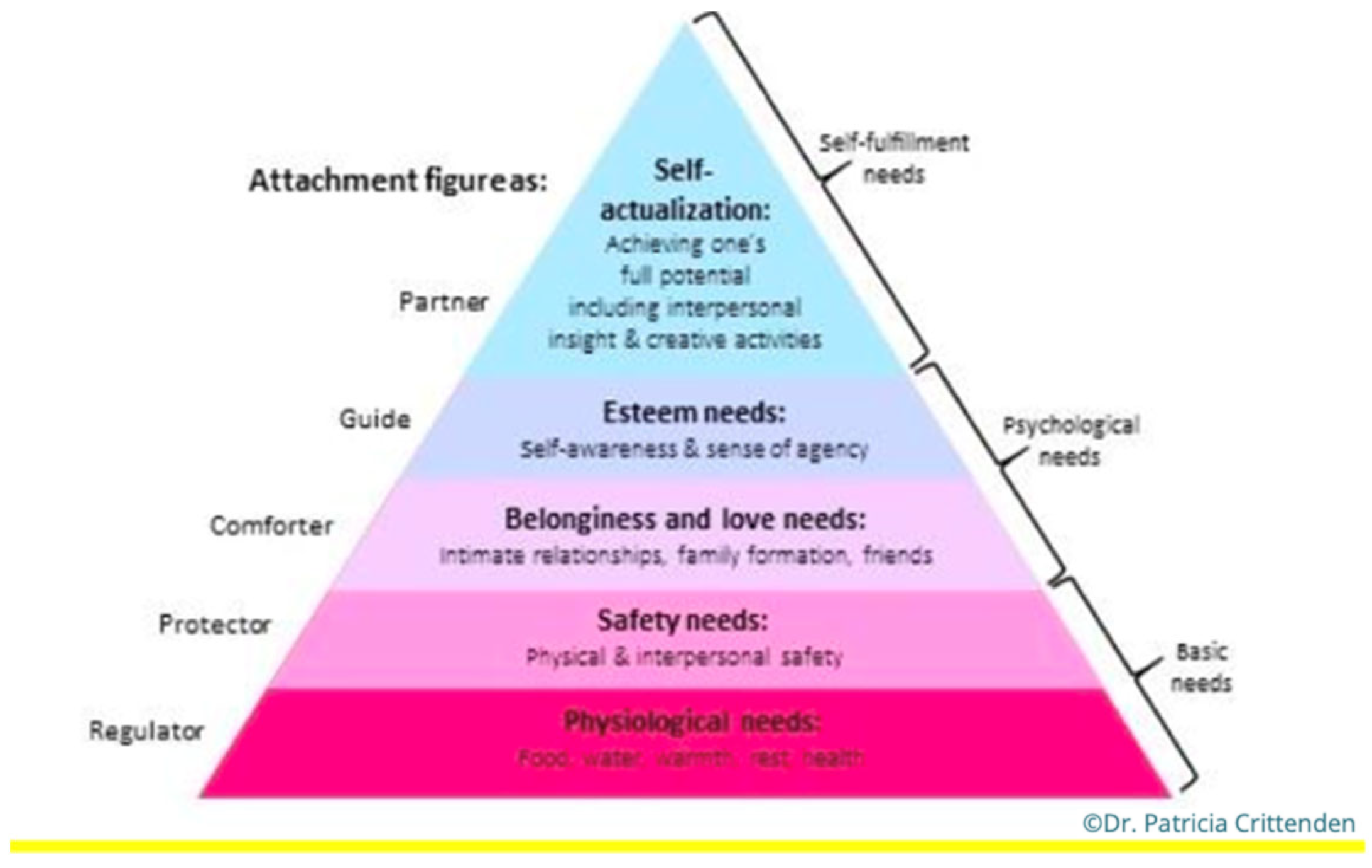

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Need (

Figure A2) was used to highlight where the family were functioning in relation to their emotional and physical needs. Alongside the traditional levels of needs such as physiological needs, the DMM proposes the type of caregiver the individual may need at each level (Safety Needs with Protector, for instance). With the Townsend family, the parents and daughter seemed to be presenting at different levels. Mr. and Mrs. Townsend had comfort and security in each other and were actively seeking support, therefore, it was felt they were presenting at the ‘Belongingness and Love Needs’ and needing a ‘Comforter’ in their attachment relationships. Joanna, as she was self-harming, questioning her identity through gender fluidity, seeking information on birth family and at an adolescent age, was presenting at the level of ‘Safety Needs’, requiring a ‘Protector’ from her attachment figures.

Understanding the family in relation to the adapted hierarchy opened up new thinking around the source of their challenges. Firstly, there was a discrepancy in the level of needs parents and daughter were feeling. According to Crittenden [

6], discrepancies give us more information on the issues faced by families as the hidden information often represents unspeakable feelings the family are facing. Joanna’s parents had a sense of comfort from each other, whilst Joanna was outside of this and possibly feeling unprotected by them. Furthermore, with Joanna in an experimental stage of life where she was exploring who she was in a deep (and age appropriate) way, having a protector attachment figure to return to may have felt imperative to her wellbeing. The exploratory assessment questions became focused on Joanna:

Who am I?

Where do I belong?

Will I be rejected?

Figure A2.

DMM version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Permission granted.

Figure A2.

DMM version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Permission granted.

Another stage of the SFF asks the family about somatic conditions as a possible link to hidden distress being embodied within the individuals. Mr. and Mrs. Townsend reported no ill health or somatic conditions, whilst there was a heavy focus on Joanna’s ill health. The family were waiting for a diagnosis relating to Joanna’s physical fits and her parents linked the start of these issues to the specific week when Joanna had unpermitted contact with her birth family. With Joanna’s parents not reporting symptoms of somatic distress, the therapist felt there was a reinforcement of the hidden aspect of Mr. and Mrs. Townsend’s emotional world, and possible turmoil. This is in contradiction to Joanna’s many somatic symptoms which include self-harm, taking an overdose and a possible cognitive/physical condition. When assessing the information presented so far, themes of unspeakable feelings and question the identity of the self were presented for both parents and daughter.

So far, the SFF had been focused on the need for safety in the face of an unknow danger for Joanna and the family. Instead of the assessing questions becoming more focused for the family as the screening went along, they were covering wider topics and failing to get to the critical issue of the family’s problem. It was when the family’s feelings around sexuality began to be explored—key not only with this referral but also a pivotal issue in the DMM in the need for humans to reproduce—that more important information started to come to the surface. When asked, Mr. and Mrs. Townsend found it extremely difficult to talk about the reasons they adopted, possible issues around infertility and reproduction, and what it might feel like for Joanna to reproduce and not create a genetic heir to their family. Farnfield [

28] stated that around 20% of adoptive parents have unresolved loss and trauma. This can impact negatively on the child more than insecure attachment strategies in parenting. Furthermore, given Joanna’s adolescent age, she was beginning to explore her own sexuality through fluidity and possible relationships, which again according to Farnfield [

28] could have been triggering trauma responses in her parents because of their unresolved loss.

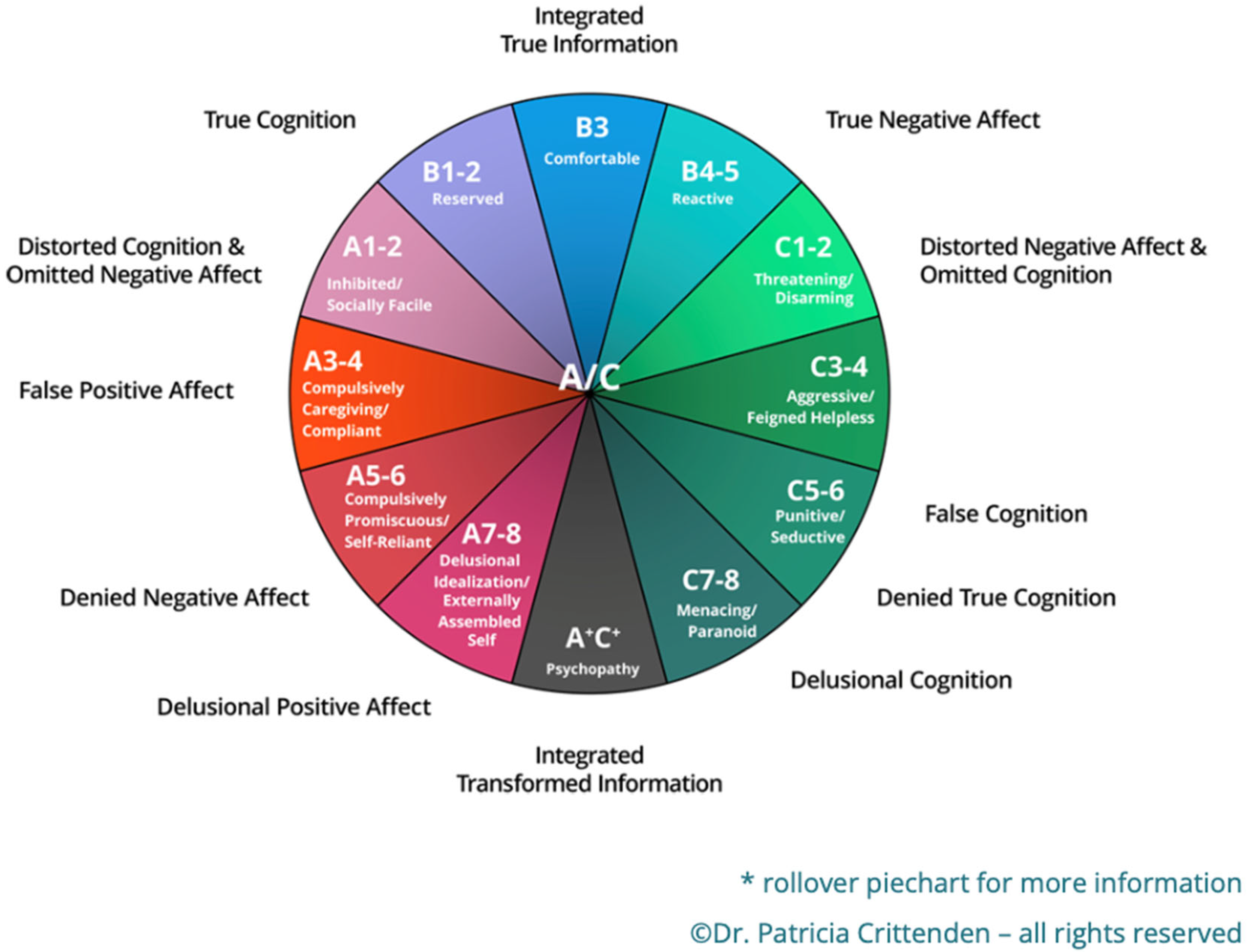

Joanna’s parents, perhaps unable to find a way to say the unspeakable distress around these issues, could have been inhibiting them in such a way that there were imperceptible changes in the attachment strategies within the home. Through the SFF, the assessing therapist proposed that the parents were using a Type A 3–4 strategy, the inhibition of negative affect and compulsive caregiving, whilst Joanna was using a Type C 3–4, moving between anger and feigned helplessness. With the difficulties for Joanna’s parents to speak about their adoption journey and feelings of intimacy and reproduction, the already conflicting attachment strategies in the family were moved into a state of ‘disorientation’ [

29]. This is when the source of distress is omitted from memory and does not fully understand why situations are happening. With the Townsend family, it may have meant that they were experiencing internal conflict about what to do because information on safety was hidden (omitted) from their conscious. The resulting behaviors are neither ‘self-protective or comfort-eliciting’ in this situation, meaning that no one in the family has their needs met. With Joanna exploring her sexuality in an overt way (and in line with her proposed Type C attachment strategy), her behaviors were in counterpoint to the inhibition of sexuality displayed by her parents. At her age, Joanna had the potential to reproduce and create her own genetic line, whilst her parents were not able to do this (the possible reason for adoption). Farnfield [

28] found that almost a third of adoptive parents focus consciously on needing a baby with the implicit goal of creating a genetic line for the future. As this is not possible in the adoptive family, an internal conflict comes to the surface for the adoptive parents, meaning that they will often pull away from the attachment relationship they have built with their adoptive child as the adoptive parents try to understand how to navigate these feelings and thoughts. This situation can confuse the adoptive child, who may have previously felt loved and secure and is now being pushed away from the safety of their adoptive parents. The child will then act out in a way to try to gain that much needed and wanted attention back from their parents. In Joanna’s situation, her conflict is perhaps being shown through self-harm, questioning her gender and femininity, and looking for answers in her birth family. The family start a cycle, with everyone showing distress, rejection, and confusion. This can then lead to a previously stable placement breaking down, with the family and professionals not being able to articulate the exact reason.

The assessing therapist felt that by the end of the SFF, there were more questions than answers. A parallel process had been played out with neither family nor therapist being able to articulate where the critical cause lay. There was an intense need for safety for Joanna and this needed to be addressed first. The parents also needed further assessment so that they would feel safe enough to share those inhibited feelings and begin to explore a way to communicate as a family again.

The Assessment of Parent–Child Interactions (ACPI): To start to understand the underlying communication styles of the family the Assessment of Parent–Child Interactions [

5] was undertaken with the full family to assess attachment behaviors and parenting capacity. The APCI is conducted face to face, over two 30-min sessions, held one week apart. The APCI contains four ‘musical activities’ which aim to highlight the nonverbal communication skills of the family, as well as levels of mutual attunement and parenting capacity. The four activities are Soft-Loud-Soft, Taking Turns, Follow my Leader, and a Free Improvisation.

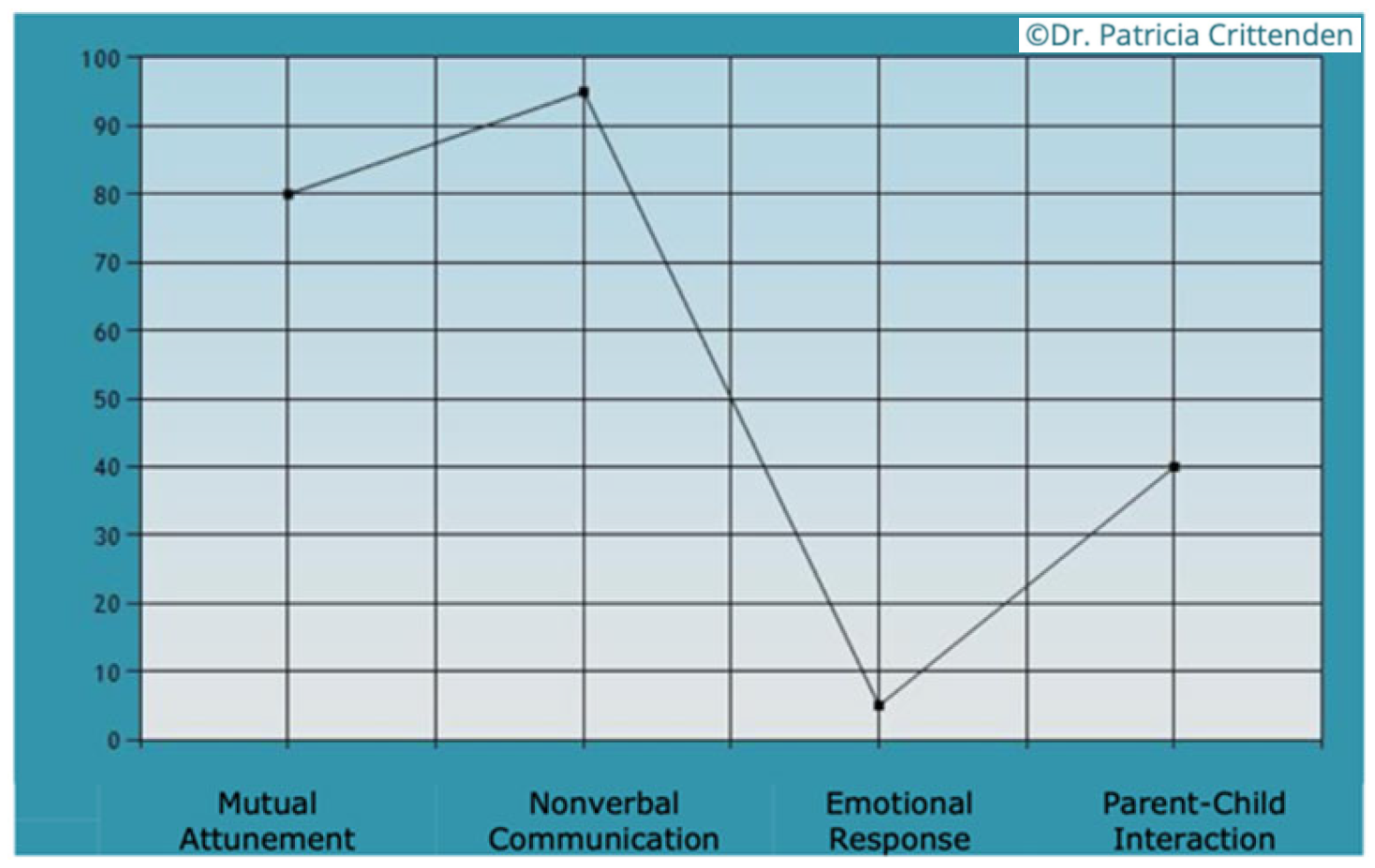

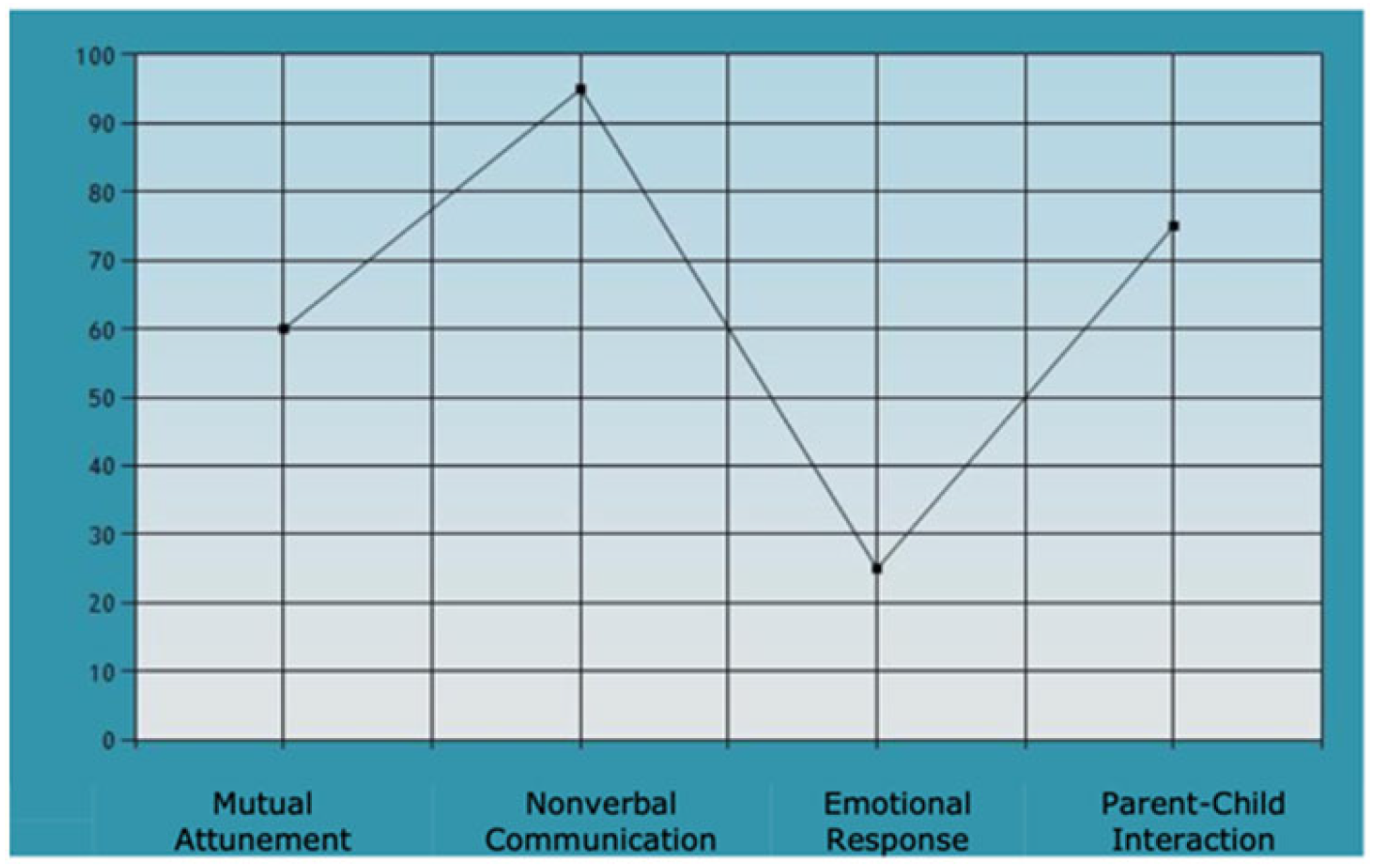

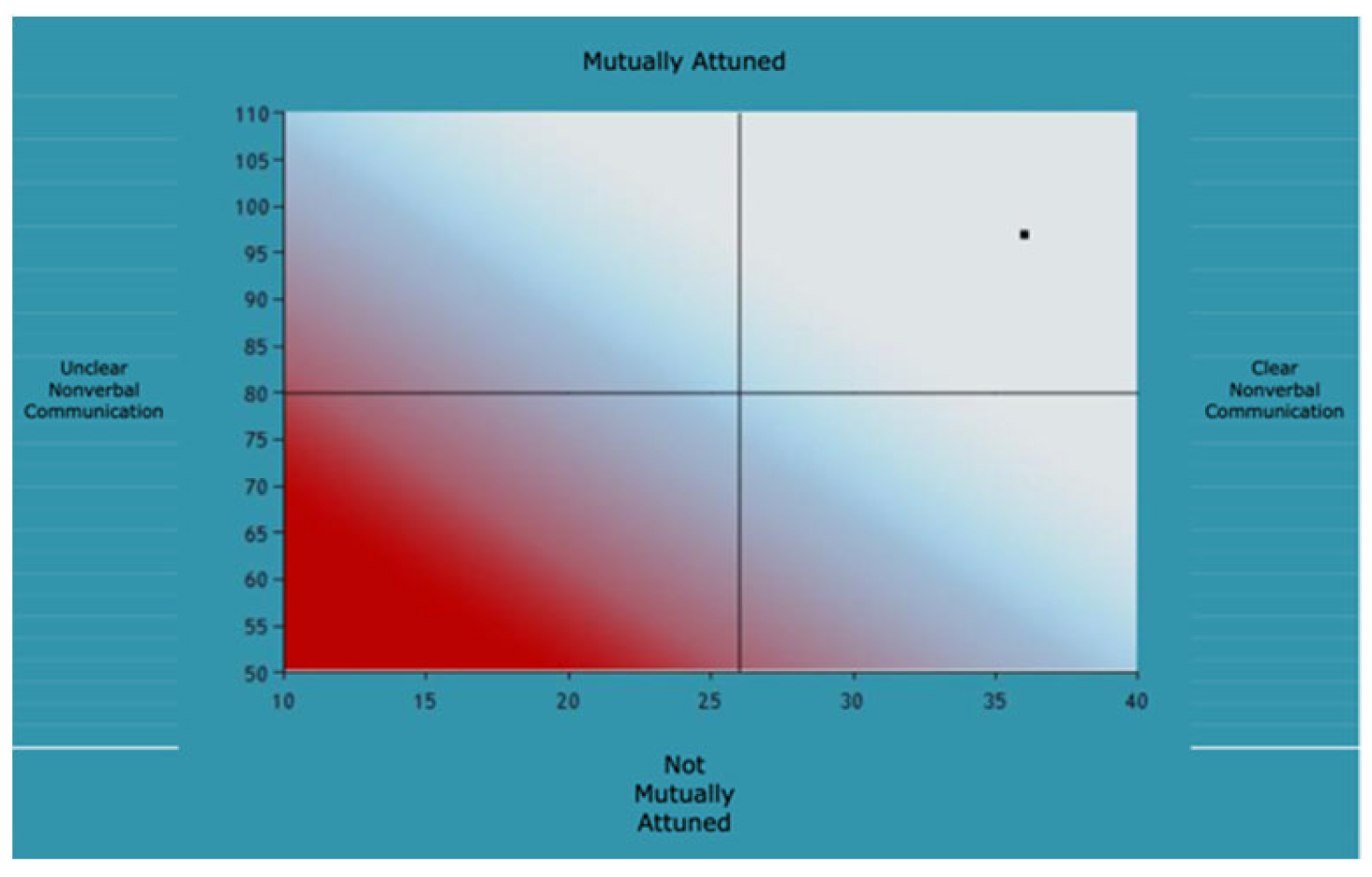

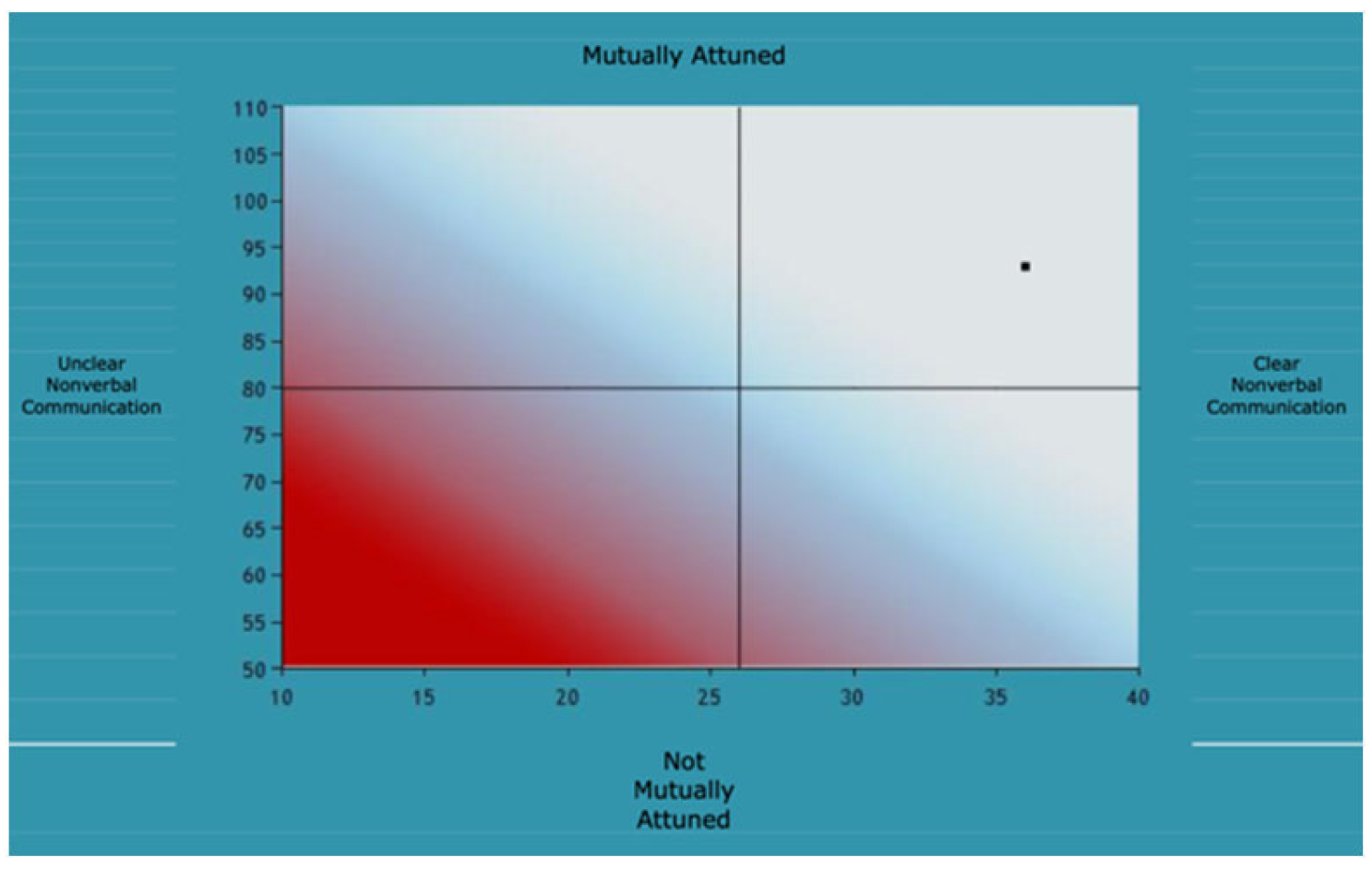

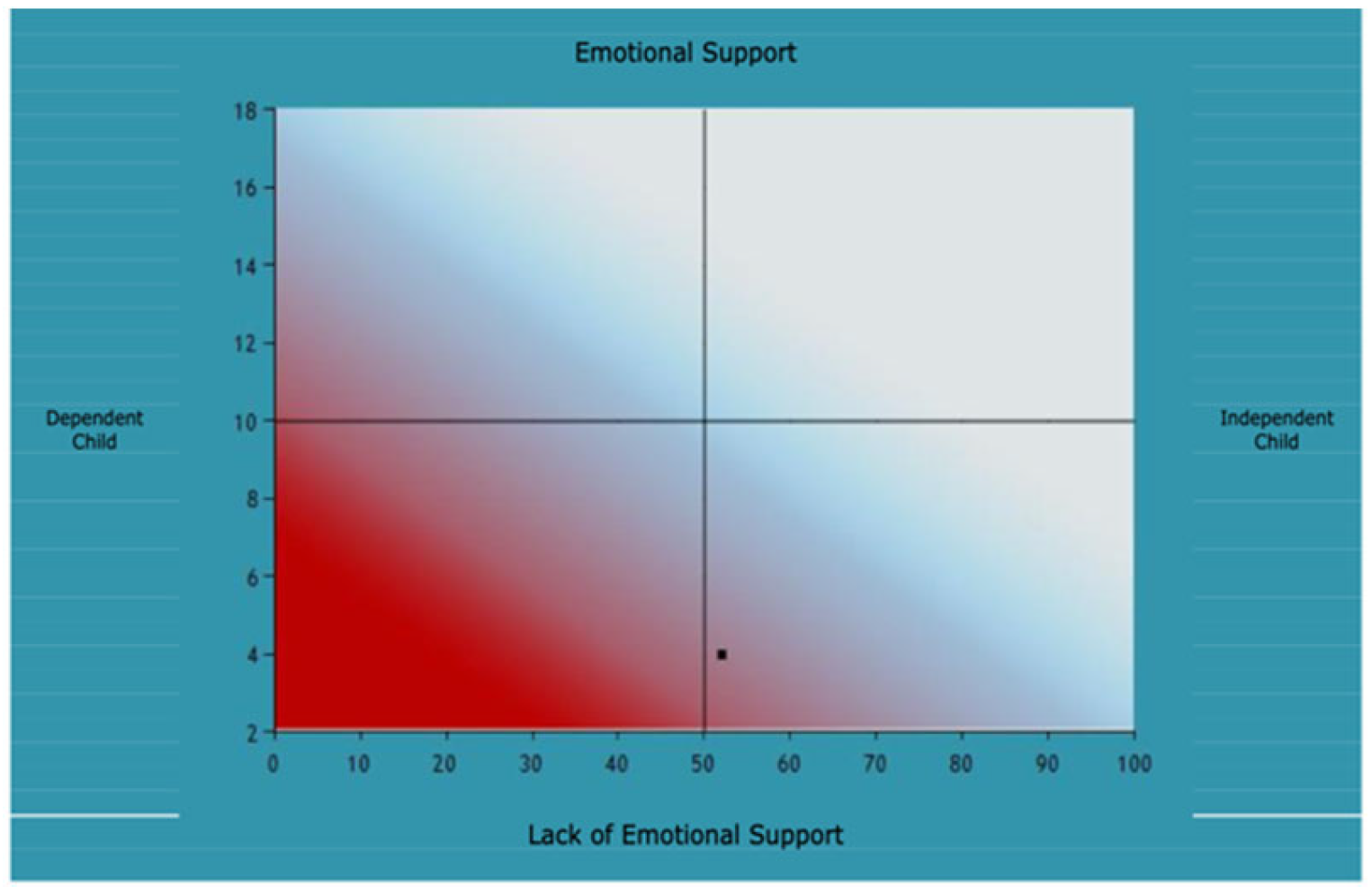

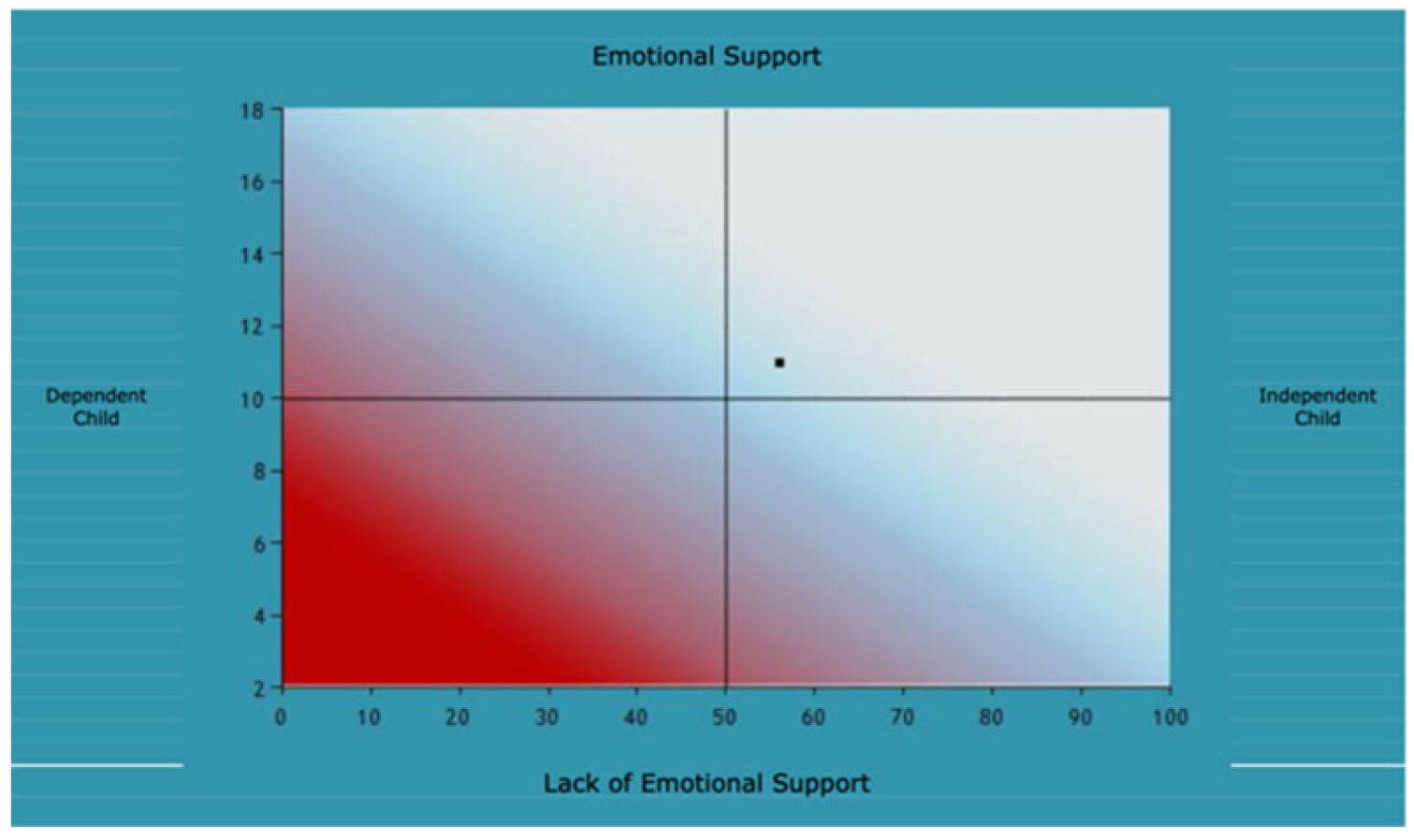

The APCI, which was conducted with both parents over two sessions each, showed that there were some successful elements of the relationships between Joanna and Mr. Townsend and Joanna and Mrs. Townsend. The charts below detail the results for each area analyzed within the APCI (

Figure A3 and

Figure A4), the attachment behavior of the dyad (

Figure A5 and

Figure A6), and the parenting capacity of the dyad (

Figure A7 and

Figure A8).

Analysis of the interactions in the music therapy sessions showed that for Joanna and Mr. Townsend, their mutual attunement, nonverbal communication, and emotional parental responses were in the normal ranges. Joanna seemed to be more playful with Mr. Townsend than with Mrs. Townsend, although there was a sense that Mr. Townsend was mindful of Joanna’s physical vulnerability, which effected the level of playfulness and enjoyment in the session. For example, during the follow my leader activity, Joanna showed high energy levels and dynamic music playing. Mr. Townsend met her gaze and facial expressions well and although he started to meet Joanna’s musical energy too, he quickly diminished his efforts, in the possible hope that Joanna would follow and not become over excited.

With Joanna and Mrs. Townsend, their mutual attunement and nonverbal communication were both in the normal range, however, the emotional parental response was low. The assessing therapist felt that Mrs. Townsend did not always respond to the emotional needs of Joanna and there were some problematic behaviors, such as Mrs. Townsend turning away from Joanna with rejection and limited face to face contact. For example, when Joanna and Mrs. Townsend were participating in the taking turns activity, Joanne started playfully, with good eye contact towards Mrs. Townsend. Mrs. Townsend took a musical turn and then moved her body and turned her face away from Joanna when she could have reciprocated Joanna’s gaze and energy. Furthermore, during the free improvisation activity at the end of the APCI, Mrs. Townsend criticized Joanna’s music, saying that she could have done better, then she moved her chair away from Joanna.

Although it must be noted that Mr. Townsend’s score for emotional parental response (

Figure A4) was in the normal range, it was still a low score. Both parents were dependent on support from the assessing therapist, which could indicate a feeling of uncomfortableness in the assessment sessions. Furthermore, the family seemed more comfortable in the structured activities, rather than the unstructured ones, again highlighting a need for supporting boundaries within the family.

Figure A3.

Joanna and Mrs. Townsend.

Figure A3.

Joanna and Mrs. Townsend.

Figure A4.

Joanna and Mr. Townsend.

Figure A4.

Joanna and Mr. Townsend.

Analysis of APCI Activities

Figure A5.

Joanna and Mrs. Townsend.

Figure A5.

Joanna and Mrs. Townsend.

Figure A6.

Joanna and Mr. Townsend.

Figure A6.

Joanna and Mr. Townsend.

Graphic representation of attachment behaviors

Figure A7.

Joanna and Mrs. Townsend.

Figure A7.

Joanna and Mrs. Townsend.

Figure A8.

Joanna and Mr. Townsend.

Figure A8.

Joanna and Mr. Townsend.

Graphic representation of parenting capacity

The output graphs for the APCI data were analyzed as per the APCI protocol (See

Appendix B for more information). For Mr. Townsend, the analysis is based on

Figure A6 and

Figure A8 and indicates APCI profile 6—MCSI, which stands for Mutually Attuned, Clear Nonverbal Communication, Supportive Parenting and Independent Child. This APCI result is classed as ‘Good Enough Parenting”. For Mrs. Townsend and Joanna,

Figure A5 and

Figure A7, the analysis indicated APCI profile 7—MCLI, which means Mutually Attuned, Clear Nonverbal Communication, Lack of Parenting Support, and Independent Child. With this profile, the lack of parenting support, along with other positive elements, may confirm the findings within the Screening Family Formulation that the family are trying to be ‘good enough’ but there are mismatches in the relationship, potentially causing conflict. With the Townsend family, there was a possibility of the inhibition of the feelings between mother and daughter impacting negatively on their communication and functioning as a dyad.

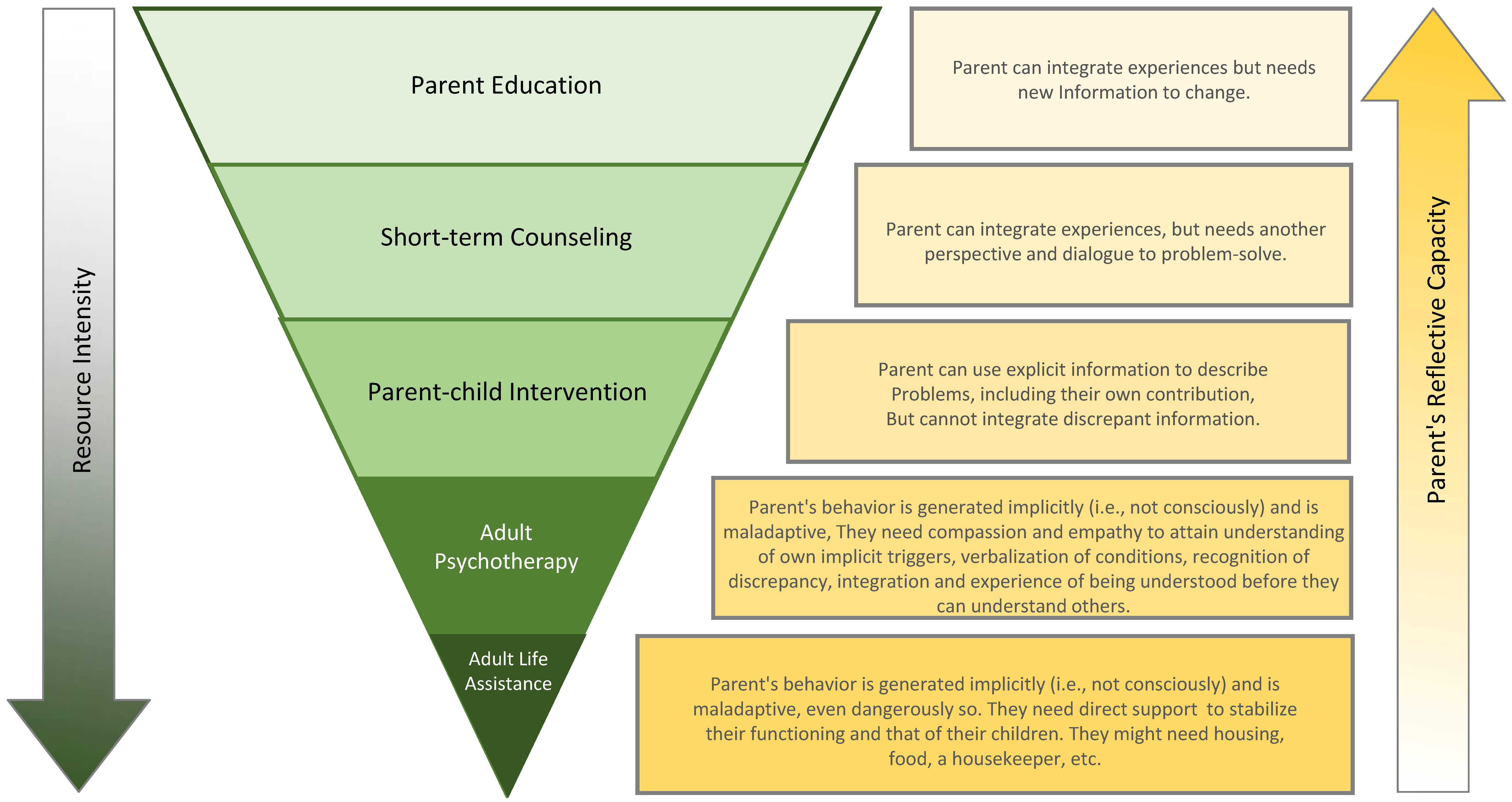

Interpretation and Evaluation of the SFF and the APCI with the family: Using the SFF alongside the APCI could be seen to confirm, or at least provide focus on, the themes that are underlying the Townsend family’s difficulties. Throughout the SFF, there were questions around the ‘not knowing’ of reasons (or lack of negative events) which could have caused the crisis within the family. There was a feeling of something being hidden and without the knowledge from the DMM—i.e., looking for discrepancies in the reported information and the heightened thought on attachment strategies. This may have been colluded between the therapist and the family. The SFF had highlighted the potentially different attachment strategies being used by the family. Joanna was using a possible Type C3–4 strategies (shown in

Figure 1 previously), oscillating between aggressive outbursts (self-harm) and helplessness (needing help with her somatic conditions). Her parents, conversely, could be seen to be using a Type A3–4, inhibiting negative affect. There was also some disorientation in the use of the strategies. As discussed earlier, disorientation is when individuals are not aware that their strategy is not functioning, and they become confused as they try to process information that feels mismatched to their feelings and behaviors. These thoughts were clarified with the addition of the APCI, where Joanna’s overt emotional requests were either ignored (during the APCI with Mrs. Townsend) or thought of as too overwhelming (with Mr. Townsend). Joanna’s feelings of not belonging and searching for an identity, although natural given her adolescent age and her experience of being adopted, were being magnified in the minimization of her feelings in the reflection of her parent’s feelings. Using the SFF’s ideas of creating questions to focus thought, Joanna might have been asking, “

If I have all of these feelings, and my parents don’t, then what is wrong with me?”.

Proposed Treatment Plans: In conclusion, the SFF and APCI complimented the assessment for the family and brought greater depth in understanding for the family. Both assessment models offer the chance for professionals to use compassion by listening to the family, curiosity when formulating questions in the SFF and noticing behaviors in the APCI and also holding hope for the family through an individualized treatment plan for the future. After the assessment was completed, and alongside the medical interventions which were necessary for Joanna, two treatment pathways were offered to the family. As the SFF had highlighted a disorientation of attachment strategies alongside gaps in information and the potential for crisis to happen, a Full Family Formulation was offered with an Adult Attachment Interview for parents and a Transition to Adulthood Interview for Joanna. The family were showing signs of low resilience and awareness, and so to support this in the more immediate future, the family were also offered art therapy for Joanna [

30] and psychological therapy for her parents. The hope for the future of the family was to bring together their opposing attachment strategies, create a place for emotions and experiences to be talked about with less shame, and to build positive feelings within the home. The Gradient of Interventions from the SFF (

Figure A9) was used to help decide the treatment plan, and the choice for which to pursue was offered to the family.

Figure A9.

The DMM Gradient of Interventions.

Figure A9.

The DMM Gradient of Interventions.