Exploring Stroke Patients’ Needs after Discharge from Rehabilitation Centres: Meta-Ethnography

Abstract

1. Introduction

Review Question

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3.1. Sample

2.3.2. Phenomena of Interest

2.3.3. Design

2.3.4. Evaluation

2.3.5. Research Type

2.3.6. Other

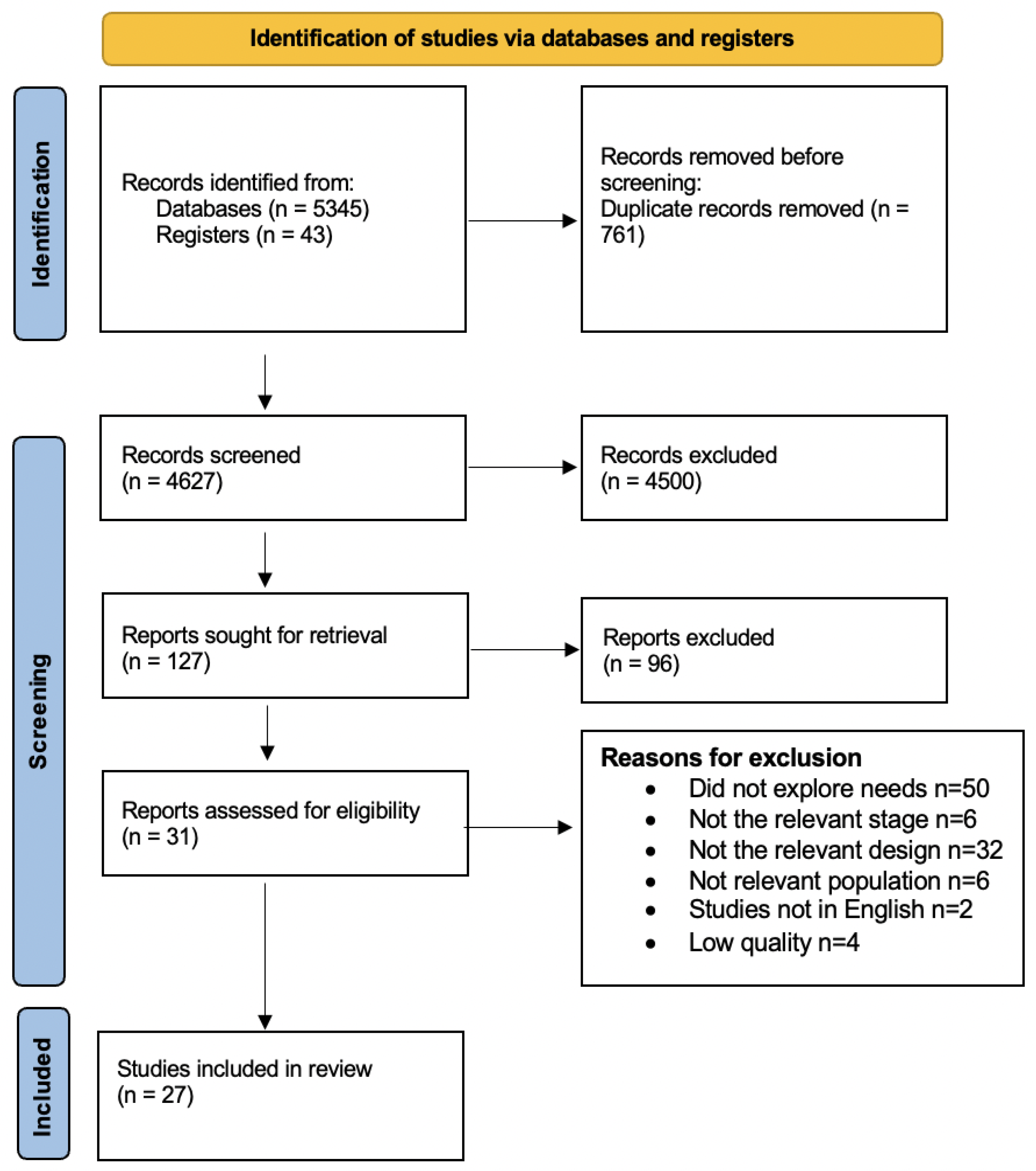

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Quality Appraisal and Certainty Assessment

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Quality Assessment and GRADE

| Authors | Geographical Location | Aim | Methodology | Participant | Time Since Stroke |

| [10] | China | To identify the rehabilitation needs of Chinese elderly patients following a stroke | Qualitative ethnographic approach. Semi-structured interview. | Fifteen stroke survivors Nine females Six males | One week before discharge from the rehabilitation ward and one month after discharge. |

| [11] | Sweden | To use patient journey mapping to explore post-discharge stroke patients’ information needs to propose eHealth services that meet their needs throughout their care and rehabilitation processes. | Qualitative research. Focus groups. | Young (<65 years) and old (≥65 years) stroke patients Female: seven Male: five | One focus group included patients with strokes more than 10 years ago. Two groups included patients with strokes less than 10 years |

| [12] | Canada | The aim of this study was to examine the rehabilitation needs of this clientele from their hospitalisation to their reintegration into the community. | Qualitative research tool was selected. The method of focus group discussion. | The patients (n = 4) Caregivers (n = 5) Healthcare providers (n = 9) Administrators (n = 7) Gender: not provided | Three patients with strokes from 2 to 3 years. One patient had a stroke from 4 to 8 years. |

| [13] | UK | To explore patients’, carers’, and health professionals’ experiences of psychological need, assessment, and support post-stroke while in hospital and immediately post-discharge. | Exploratory study. Qualitative semi-structured interviews and focus groups. | Thirty-one stroke patients, twenty-eight carers, and sixty-six health professionals. Male: eighteen patients, nine carers Female: thirteen patients nineteen carers Health professionals’ genders were not provided. | Mean length of 171.23 days between discharge and interview. |

| [14] | Australia | To identify patients’ and carers’ perceived barriers to accessing and understanding information about strokes. | Semi-structured interviews at two points in time. | Initial interviews were conducted with 34 stroke patients and 18 carers, and follow-up interviews were completed with 27 patients and 16 carers. Fourteen female patients Thirteen female carers | Prior to and 3 months following discharge from an acute stroke unit. |

| [25] | Canada | To explore the stroke education perspectives in a Canadian rehabilitation centre to illustrate one approach for addressing this problem. | Qualitative description study was overlaid by phenomenology. Face-to-face semi-structured interview. | Three patients and three caregivers. Three male patients Three female caregivers | Not identified. |

| [26] | UK | To explore stroke survivors’ needs and their perceptions of whether a community stroke scheme met these needs. | A qualitative study using a phenomenological approach. Semi-structured face-to-face interviews. | Twelve stroke survivors. Female: five Male: seven | Mean of 26 months post-stroke. |

| [27] | Australia | To explore the experiences of community-dwelling stroke survivors at one, three, and five years using a community-based, cross-sectional study. | A modified, grounded theory approach. Semi-structured interview. | Ninety-one stroke survivors at one, three, and five years after stroke. Forty-seven males Forty-four females | Cohort One: People who had had a stroke 1 year prior to recruitment. Cohort Three: People who had had a stroke 3 years prior to recruitment. Cohort Five: People who had had a stroke 5 years prior to recruitment. |

| [28] | Iran | To illuminate how stroke survivors experience and perceive life after strokes. | Grounded theory approach using semi-structured interviews. | Ten stroke survivors. Male: six Female: four | Patients had strokes within the past 3–6 months. |

| [29] | UK | To investigate how contextual factors, as described by the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), impact stroke survivors’ functioning and how needs are perceived in the long term after strokes. | Semi-structured, in-depth interviews. | Thirty-five stroke survivors. Males: 49% Females: 51% | Total of 49% had strokes within 1 to 2 years. Total of 31% had strokes within 3 to 5 years. Total of 6% had strokes within 6 to 8 years. Total of 14% had stroke more than 9 years. |

| [30] | UK | To investigate how younger stroke survivors’ experiences of care are shaped by the field of stroke and how, in navigating stroke care, individuals seek to draw on different forms of capital in adjusting to life after strokes. | One-to-one, semi-structured interviews. | Thirty-one stroke survivors were interviewed. In ten interviews, carers also took part. Nineteen males Twelve females | Patient had stroke within 6 weeks and 28 months. |

| [31] | Norway | To explore young and midlife stroke survivors’ experiences with the health services and to identify long-term follow-up needs. | This qualitative study applied a hermeneutic phenomenological approach. Two cohort, in-depth interviews. | Sixteen stroke survivors. Five females Eleven males | Patient had stroke within 1.5 to 10 years after stroke onset. |

| [32] | Sweden | To explore stroke survivors’ experiences of healthcare-related facilitators and barriers concerning return to work after stroke. | Qualitative study. Focus groups. | Twenty stroke survivors. Seven females Thirteen males | Patient had been referred to stroke rehabilitation within 180 days after stroke onset. |

| [33] | Australia | To examine the unmet needs of younger stroke survivors in inpatient and outpatient healthcare settings and identify opportunities for improved service delivery. | Qualitative descriptive approach. In-depth, semi-structured interviews. | Nineteen young stroke survivors. Ten females and nine males. | Patients had stroke within 6 months to 24 years. |

| [34] | Canada | To identify the educational needs of older adults who have had a stroke in order to support their participation in leisure activities that promote cognitive health. | A descriptive study. Mixed-methods design was used with an emphasis on qualitative data and involving semi-structured interviews. | Twenty people. Fourteen males Six females | Mean of 8 months post-stroke. Mean of 5.9 months post-discharge. |

| [35] | Australia | To explore the needs and experiences of people who cease driving following a stroke with the aim of informing clinical practice. | Qualitative phenomenological approach. Semi-structured interviews. | Twenty-four stroke participants. Seventeen males Seven females | Mean of 5 years post-stroke. |

| [36] | UK | To develop local stroke services by involving, in a meaningful way, those affected by stroke in identifying and prioritising service development issues. | An action research framework. A combination of semi-structured interviews and focus groups with both patients and carers. | N=35 Patients recruited from hospitals (n = 30) Females: 53% Patients recruited from community (n = 5) Females: 52% | Not identified. |

| [37] | UK | To identify the information needs of patients and their informal carers at various stages post-stroke with the aim of developing a database from which individualised information packages could be provided. | Grounded theory approach. In-depth, qualitative, semi-structured interviews. | Nine were interviews with patients, ten were interviews with patients and carers together, and two were interviews with carers only (totalling thirty-one people in all). Eleven were male and ten were female. | Seven interviews were carried out with patients and/or carers immediately post-stroke. Five immediately post-discharge. Nine between 2 months and 1 year post-discharge. |

| [38] | UK | To identify the long-term support needs of patients with prevalent stroke, and their carers identified from practice stroke registers. | Qualitative study. Focus groups. | Twenty-seven patients and six carers subsequently participated in the focus groups/interviews. Nineteen females Fourteen males | Median of 4 years post first stroke. Median of 2.5 years since last stroke. |

| [39] | US | To study the perspectives and experiences of stroke survivors and partners of stroke survivors regarding sexual issues and perceived rehabilitation needs. | Qualitative, exploratory, Individual, semi-structured interviews | Fifteen stroke survivors and fourteen partners of stroke survivors. Sixteen males Thirteen females | Patients: median of 45 months post-stroke. Partners: median of 51.5 months post-stroke. |

| [40] | USA | To examine rural Appalachian Kentucky stroke survivors’ and caregivers’ experiences of receiving education from healthcare providers with the long-term goal of optimizing educational interactions and interventions for an underserved population. | Qualitative descriptive study. Semi-structured interviews. | Thirteen stroke survivors and twelve caregivers. Sixteen females Nine males | Mean of 3.6 years post-stroke. |

| [41] | Canada | To explore the experiences and needs of Chinese stroke survivors and family caregivers as they return to community living using the Timing it Right Framework as a conceptual guide. | Qualitative interviews In person or telephone interviews depending on the participant’s preference. | Eighteen participants including five stroke survivors and thirteen caregivers. Nine females Nine males | Patients: median of 6 months post-discharge. Caregivers: median of 8 months post-discharge. |

| [42] | Canada | To report the experiences and perceptions of people with stroke and their caregivers in the existing continuum of stroke care, social services, and rehabilitation in the province of Québec (Canada). | Phenomenological qualitative study. Focus groups. | Sixty-eight participants were recruited and attended the ten focus groups. Thirty-seven stroke patients and thirty-one carers. Twenty-nine males Thirty-nine females | Mean of 2.6 years post-discharge. |

| [43] | Australia | To explore community-dwelling first-time stroke survivors and family caregivers’ perceptions of being engaged in stroke rehabilitation. | An interpretive study design. Face-to-face using a semi-structured interview. | Twelve and ten caregivers. Twelve males Ten females | Not identified. |

| [44] | Canada | To gain insight into healthcare and social structures from the perspective of patients and caregivers that can better support long-term stroke recovery. | Qualitative descriptive design. Semi-structured interview. | A total of twenty-four participants were recruited: sixteen stroke survivors (female = five, male = eleven, aged 48–87), four spouses, (females aged 62–80), three stroke recovery group coordinators (female), and one speech pathologist (female). | Mean of 8.74 years since stroke. |

| [45] | Malaysia | To explore the perception of rehabilitation professionals and people with stroke towards long-term stroke rehabilitation services and potential approaches to enable provision of these services. | Qualitative study using focus groups. | Fifteen rehabilitation professionals. Eight stroke survivors. Fourteen females Nine males | Patients had stroke from 1 to 2 years. |

| [46] | UK | This study explored needs identified by patients, how they were addressed by the six-month review (6MR), and whether or not policy aspirations for the review were substantiated by the data. | Philosophy: critical realism. Design: multiple case study design. Methods: interviews. | Forty-six patients and twenty-eight professionals. Gender was not provided. | Patients and carers were interviewed at about six weeks post-discharge after their 6MR and, where possible, after their annual review. |

| Authors | Findings | ||||

| [10] | Five themes: informational needs; psychological needs; physical needs; social needs; spiritual needs. | ||||

| [11] | Five themes: A holistic view of the care process; understanding the illness; collaboration with care providers; tracking the rehabilitation process; practical guidance through healthcare and community services. | ||||

| [12] | Nutrition; body condition; personal care; communication; housing; mobility; responsibilities; interpersonal relationships including sexuality; community living; leisure activities; psychological; cognitive. | ||||

| [13] | Two themes: Minding the gap and psychological expertise. | ||||

| [14] | Three themes: limited availability and suitability of information; the hospital environment; patient and carer factors. | ||||

| [25] | Five themes: secondary prevention; rate of recovery; knowledge collection; transition to home; adherence to home programme. | ||||

| [26] | Three themes: creating a social self; provision of ‘responsive services’ in the community ; informal support network. | ||||

| [27] | Three themes: knowledge about stroke; communication with the health system; influences on transition home. | ||||

| [28] | Two themes: functional disturbance and lack of social support. | ||||

| [29] | Environmental factors; support and relationships; products and technology; services, systems, and policies; attitude; personal factors; life experiences; social position; personal attitude. | ||||

| [30] | Four themes: healthcare professional as expert; expectation of involvement in care; social capital; variations in economic capital. | ||||

| [31] | Two themes: difficulties accessing health services and lack of tailored follow-up services. | ||||

| [32] | Two themes: requesting rehabilitation planning, healthcare information, and coordination and increased support in daily life would facilitate return to work. | ||||

| [33] | Three themes: inadequately addressed psycho-emotional and cognitive needs after young stroke; isolation from lack of information and structured support; failure to deliver age-relevant patient-centred care. | ||||

| [34] | Three themes: activities perceived to be beneficial in promoting cognitive health; continuity versus changes in participation post-stroke; factors influencing leisure participation. | ||||

| [35] | Four themes: life without driving; key times of need; alternatives and other ways; carer support and assistance. | ||||

| [36] | Four themes: prevention; immediate care; early and continuing rehabilitation; transfer of care and long-term support. | ||||

| [37] | Three themes: clinical information; practical information; information on continuing care and resources in the community. | ||||

| [38] | Three themes: psychological and emotional problems; information needs; contact with services. | ||||

| [39] | Seven themes: sense of loss and functional changes affect sexuality; relationship changes affect sexual functioning; difficult to talk about sex; little or no discussion of post-stroke sexuality by rehabilitation professionals; need to tailor education about sex to the individual/ couple; timing is key in presenting information about sex after stroke; provider rapport and competence is vital to discussing sexual issues. | ||||

| [40] | Five themes: providers of education; receivers of education; content of education; delivery of education; timing of education. | ||||

| [41] | Two themes: information and training needs of stroke survivors and caregivers change over time, and Chinese resources are needed across care environments. | ||||

| [42] | Four themes: accessibility of care; appropriateness of care; expertise of the healthcare workers and continuity of care | ||||

| [43] | These themes: readiness to return home; coping with care transition; dealing with fragmented rehabilitation services and uncertainty about ongoing rehabilitation. | ||||

| [44] | Two themes: experiences of managing stroke and resources for support. | ||||

| [45] | Four themes: the needs for continuity of care; beliefs about long-term rehabilitation; perceived barriers to long-term stroke rehabilitation; approaches to long-term rehabilitation. | ||||

| [46] | Two themes: perceived needs for community stroke rehabilitation and perceived need for information, education, and support. | ||||

3.2.1. Major Theme One: Limited Availability and Suitability of Information

I cannot understand what caused it to happen … I did not know what a stroke was.[27] (p. 85)

That [information] was fairly zero, actually! I would have liked more information about how to prevent another stroke and also … any alarm signals.[46] (p. 5)

“I would like to know what services were available, you know.”[27] (p. 87)

Information Delivery Methods

“didn’t have relevant brochures … not a lot of detail.”[14] (p. 72)

“Participants described the need for multiple repetitions of education over time, across the continuum of care, and into the chronic phase of stroke.”[40] (p. 20)

‘I need to learn, sometimes on radio and television they have programs about stroke recovery. I listen and use the information. Some guidelines are very important and can help us to improve our life style after stroke.’[28] (p. 251)

Challenges for Information Delivery

“You were lucky to get a doctor to come and speak with [you].”[14] (p. 74)

“The doctors always said … please feel free to ring up … But it’s like all these things, you don’t know the questions to ask. You’ve no idea.”[46] (p. 5)

“The physicians here at the hospital did not agree with the stroke rehab physicians about when I was going to start working.”[32] (p. 745)

3.2.2. Major Theme Two: Adequacy of Care and Services

“They don’t really help you get back into life, do they? They just sort of, you have a stroke, you have physio and that’s it.”[30] (p. 1915)

“What they did was they sent me home a couple of weeks before time and they figured that … I would realise, you know, exactly what I would need so and that’s why they did it.”[25] (p. 283)

“there’s no way [the] one hour a week that the government gives you is going to fix people.”[33] (p. 1701)

“it should have been a formal process to gain access to a psychologist” and it would have been beneficial from an earlier time point, such as from the acute hospital.”[33] (p. 1700)

“Initially, I was motivated. After several months, I don’t feel that excited anymore.”[45] (p. 6)

“it was almost like [being] throwing in the deep end. I’ve never showered anyone in my life beforep … we just sort of muddled through … maybe like when you’re leaving rehab inpatient, someone probably should go through with the partner of the person about showering, medications.”[43] (p. 78)

“I wish that there would be a therapy group for people who are in the same situation… how we can help each other, what kind of demands can I make at work. I would be open to that after 4 months, when I have come to terms with my situation a bit and it would’ve been OK to share it with others.”[32] (p. 744)

“Definitely, one of the most important necessities for every human being in the world is social insurance that supports people with stroke so they have a stable community.”[28] (p. 251)

“often the seats on trains and buses were full, disabled parking spots were often taken and that there was increased waiting time associated with public transport.”[35] (p. 277)

“It would have been good to get a plan earlier. To receive [a rehabilitation] contact earlier.”[32] (p. 744)

“It’s a long time to wait before they came round, I wanted to get moving because the physio was so good in hospital … but then when you come home there’s nothing … I wanted to just get going and build on what I was doing in the hospital.”[46] (p. 3)

“You should get some kind of contact person… someone who calls and checks on you “how is it now, are you experiencing any problems?” could refer you to, well, here or there.”[32] (p. 744)

“No automatic follow up on what I am doing. That’s the biggest problem. You’ve got to have some input…There is no follow up unless you do it yourself.”[43] (p. 80)

Needs of Younger Patients

“they just treated me like I was 70 years old but I’m actually 35” and “it’s like they put you into a box; you had a stroke, so this is how we deal with people that had a stroke.”[33] (p. 1701)

Carer Needs

| Review Finding | CERQual Confidence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited availability and suitability of information | Needs for information on stroke pathology | Pre stroke information After stroke information | High confidence | |

| Needs for information on stroke recovery | Need for information on stroke rehabilitation | High confidence | ||

| Need for guidance on health services | Moderate confidence | |||

| Adequate information delivery | Amount | Moderate confidence | ||

| Relevance | Low confidence | |||

| Time | Moderate confidence | |||

| Format | High confidence | |||

| Adequate care and services | Intervention needs | Programme Intensity | Low confidence | |

| Return to work | Low confidence | |||

| Driving rehabilitation | Low confidence | |||

| Sex rehabilitation | Low confidence | |||

| Leisure activities | Low confidence | |||

| Psychological support | High confidence | |||

| Social needs | Motivation | Peer support | Moderate confidence | |

| Family support | High confidence | |||

| Income support | High confidence | |||

| Travel support | High confidence | |||

| Engagement in goal setting | Clear plan | Low confidence | ||

| Individualised plan | Low confidence | |||

| Care continuity | Ongoing care | High confidence | ||

| Follow-up services | High confidence | |||

| Communication | Contact with health services | High confidence | ||

| Coordinator | Low confidence | |||

| Trained professionals | Moderate confidence | |||

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implication for Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stroke Association. Physical Effect of Stroke. 2019. Available online: https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/physical_effects_of_stroke.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Feigin, V.L.; Norrving, B.; Mensah, G.A. Global burden of stroke. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaracz, K.; Grabowska-Fudala, B.; Górna, K.; Kozubski, W. Consequences of stroke in the light of objective and subjective indices: A review of recent literature. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2014, 48, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truelsen, T.; Bonita, R. The worldwide burden of stroke: Current status and future projections. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2008, 92, 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Haley, W.E. Family caregiving for patients with stroke: Review and analysis. Stroke 1999, 30, 1478–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, B.; Deng, Y.; Fan, J.C.; Zhang, L.; Song, F. Long-term unmet needs after stroke: Systematic review of evidence from survey studies. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, B.J.; Ellen Young, M.; Cox, K.J.; Martz, C.; Rae Creasy, K. The crisis of stroke: Experiences of patients and their family caregivers. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2011, 18, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, N.E.; Kilkenny, M.; Naylor, R.; Purvis, T.; Lalor, E.; Moloczij, N.; Cadilhac, D.A.; National Stroke Foundation. Understanding long-term unmet needs in Australian survivors of stroke’. Int. J. Stroke 2014, 9, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKevitt, C.; Fudge, N.; Redfern, J.; Sheldenkar, A.; Crichton, S.; Rudd, A.R.; Forster, A.; Young, J.; Nazareth, I.; Silver, L.E.; et al. Self-Reported Long-Term Needs After Stroke. Stroke 2011, 42, 1398–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, M.H.; Mackenzie, A.E. Chinese elderly patients’ perceptions of their rehabilitation needs following a stroke. J. Adv. Nurs. 1999, 30, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoody, N.; Koch, S.; Krakau, I.; Hägglund, M. Post-discharge stroke patients’ information needs as input to proposing patient-centred eHealth services. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, L.R.; Viscogliosi, C.; Desrosiers, J.; Vincent, C.; Rousseau, J.; Robichaud, L. Identification of rehabilitation needs after a stroke: An exploratory study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M.; Ryan, T.; Gardiner, C.; Jones, A. Psychological and emotional needs, assessment, and support post-stroke: A multi-perspective qualitative study. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2016, 24, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eames, S.; Hoffmann, T.; Worrall, L.; Read, S. Stroke patients’ and carers’ perception of barriers to accessing stroke information. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2010, 17, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafsteinsdóttir, T.B.; Vergunst, M.; Lindeman, E.; Schuurmans, M. Educational needs of patients with a stroke and their caregivers: A systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 85, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindus, D.M.; Mullis, R.; Lim, L.; Wellwood, I.; Rundell, A.V.; Abd Aziz, N.A.; Mant, J. Stroke survivors’ and informal caregivers’ experiences of primary care and community healthcare services–a systematic review and meta-ethnography. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192533. [Google Scholar]

- Kamenov, K.; Mills, J.-A.; Chatterji, S.; Cieza, A. Needs and unmet needs for rehabilitation services: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Ding, C.; Mei, Y.; Wang, P.; Ma, F.; Zhang, Z.-X. Unmet care needs of community-dwelling stroke survivors: A protocol for systematic review and theme analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, B.; Mei, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Fu, Z. The Unmet Needs of Community-Dwelling Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblit, G.W.; Hare, R.D.; Hare, R.D. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- France, E.F.; Cunningham, M.; Ring, N.; Uny, I.; Duncan, E.A.; Jepson, R.G.; Maxwell, M.; Roberts, R.J.; Turley, R.L.; Booth, A.; et al. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundy, A.; Heneghan, N. Meta-ethnography. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 15, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, M.; Robinson, K.; Pettigrew, J.; Galvin, R.; Stanley, M. Qualitative synthesis: A guide to conducting a meta-ethnography. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 81, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI. JBI Qualitative Data Extraction Tool. 2019. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/3290005651/Appendix+2.3%3A+JBI+Qualitative+data+extraction+tool (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Shook, R.; Stanton, S. Patients’ and caregivers’ self-perceived stroke education needs in inpatient rehabilitation. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2016, 23, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Harrington, R.; Duggan, Á.; Wood, V.A. Meeting stroke survivors’ perceived needs: A qualitative study of a community-based exercise and education scheme. Clin. Rehabil. 2010, 24, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.H.; Magin, P.; Pollack, M.R.P. Stroke Patients’ Experience with the Australian Health System: A Qualitative Study. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2009, 76, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvandi, A.; Heikkilä, K.; Maddah, S.S.B.; Khankeh, H.R.; Ekman, S.L. Life experiences after stroke among Iranian stroke survivors. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2010, 57, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumathipala, K.; Radcliffe, E.; Sadler, E.; Wolfe, C.D.; McKevitt, C. Identifying the long-term needs of stroke survivors using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Chronic Illn. 2012, 8, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, E.; Daniel, K.; Wolfe, C.D.; McKevitt, C. Navigating stroke care: The experiences of younger stroke survivors. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 1911–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, R.; Kirkevold, M.; Sveen, U. Young and Midlife Stroke Survivors’ Experiences with the Health Services and Long-Term Follow-Up Needs. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2015, 47, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gard, G.; Pessah-Rasmussen, H.; Brogårdh, C.; Nilsson, Å.; Lindgren, I. Need for structured healthcare organization and support for return to work after stroke in Sweden: Experiences of stroke survivors. J. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 51, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, J.; Luker, J.; Thijs, V.; Bernhardt, J. How can stroke care be improved for younger service users? A qualitative study on the unmet needs of younger adults in inpatient and outpatient stroke care in Australia. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, V.; Carbonneau, H.; Provencher, V.; Rochette, A.; Giroux, D.; Verreault, C.; Turcotte, S. Participation in leisure activities to maintain cognitive health: Perceived educational needs of older adults with stroke. Loisir Société/Soc. Leis. 2019, 42, 4–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, J.; Turpin, M.; McKenna, K.; Kubus, T.; Lambley, S.; McCaffrey, K. The Experiences and Needs of People Who Cease Driving After Stroke. Brain Impair. 2009, 10, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.P.; Auton, M.F.; Burton, C.R.; Watkins, C.L. Engaging service users in the development of stroke services: An action research study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 1270–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiles, R.; Pain, H.; Buckland, S.; McLellan, L. Providing appropriate information to patients and carers following a stroke. J. Adv. Nurs. 1998, 28, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, R.; Rogers, H.; Lester, H.; McManus, R.J.; Mant, J. What do stroke patients and their carers want from community services? Fam. Pract. 2006, 23, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, M.A.; Finkelstein, M. Perspectives on poststroke sexual issues and rehabilitation needs. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2010, 17, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzl, M.M.; Harrison, A.; Hunter, E.G.; Kuperstein, J.; Sylvia, V.; Maddy, K.; Campbell, S. “A lot of things passed me by”: Rural stroke survivors’ and caregivers’ experience of receiving education from health care providers. J. Rural. Health 2016, 32, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, E.H.; Szeto, A.; Richardson, D.; Lai, S.H.; Lim, E.; Cameron, J.I. The experiences and needs of C hinese-C anadian stroke survivors and family caregivers as they re-integrate into the community. Health Soc. Care Community 2015, 23, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne, M.E.; Richards, C.; Azzaria, L.; Rosa-Goulet, M.; Clément, L.; Pelletier, F. Perspective of patients and caregivers about stroke rehabilitation: The Quebec experience. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2019, 26, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xiao, L.D.; De Bellis, A. First-time stroke survivors and caregivers’ perceptions of being engaged in rehabilitation. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartford, W.; Lear, S.; Nimmon, L. Stroke survivors’ experiences of team support along their recovery continuum. BMC health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Nordin, N.A.; Aziz, N.A.A.; Abdul Aziz, A.F.; Ajit Singh, D.K.; Omar Othman, N.A.; Sulong, S.; Aljunid, S.M. Exploring views on long term rehabilitation for people with stroke in a developing country: Findings from focus group discussions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahamson, V.; Wilson, P.M. How unmet are unmet needs post-stroke? A policy analysis of the six-month review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, C.L.; Leathley, M.J.; Chalmers, C.; Curley, C.; Fitzgerald, J.E.; Reid, L.; Williams, J. Promoting stroke-specific education. Nurs. Stand. 2012, 26, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, V. Best practices for stroke patient and family education in the acute care setting: A literature review. Medsurg Nurs. 2013, 22, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Forster, A.; House, A.; Knapp, P.; Wright, J.J.; Young, J. Information provision for stroke patients and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, CD001919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Party, I.S.W. National Clinical Guideline for Stroke; Royal College of Physicians: London, UK, 2012; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Huijbregts, M.P.; McEwen, S.; Taylor, D. Exploring the feasibility and efficacy of a telehealth stroke self-management programme: A pilot study. Physiother. Can. 2009, 61, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.; Taylor, S.J.; Eldridge, S.; Ramsay, J.; Griffiths, C.J. Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, CD005108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Temehy, B.; Rosewilliam, S.; Alvey, G.; Soundy, A. Exploring Stroke Patients’ Needs after Discharge from Rehabilitation Centres: Meta-Ethnography. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100404

Temehy B, Rosewilliam S, Alvey G, Soundy A. Exploring Stroke Patients’ Needs after Discharge from Rehabilitation Centres: Meta-Ethnography. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(10):404. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100404

Chicago/Turabian StyleTemehy, Basema, Sheeba Rosewilliam, George Alvey, and Andrew Soundy. 2022. "Exploring Stroke Patients’ Needs after Discharge from Rehabilitation Centres: Meta-Ethnography" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 10: 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100404

APA StyleTemehy, B., Rosewilliam, S., Alvey, G., & Soundy, A. (2022). Exploring Stroke Patients’ Needs after Discharge from Rehabilitation Centres: Meta-Ethnography. Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100404