Perseverative Cognition and Snack Choice: An Online Pilot Investigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Snack Choice Task

2.3.2. Stimuli

2.3.3. Questionnaires

The Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ)

The Brief State Rumination Inventory (BSRI)

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Ethics

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Treatment of Data

3.2. Effect of PC on Snack Choice

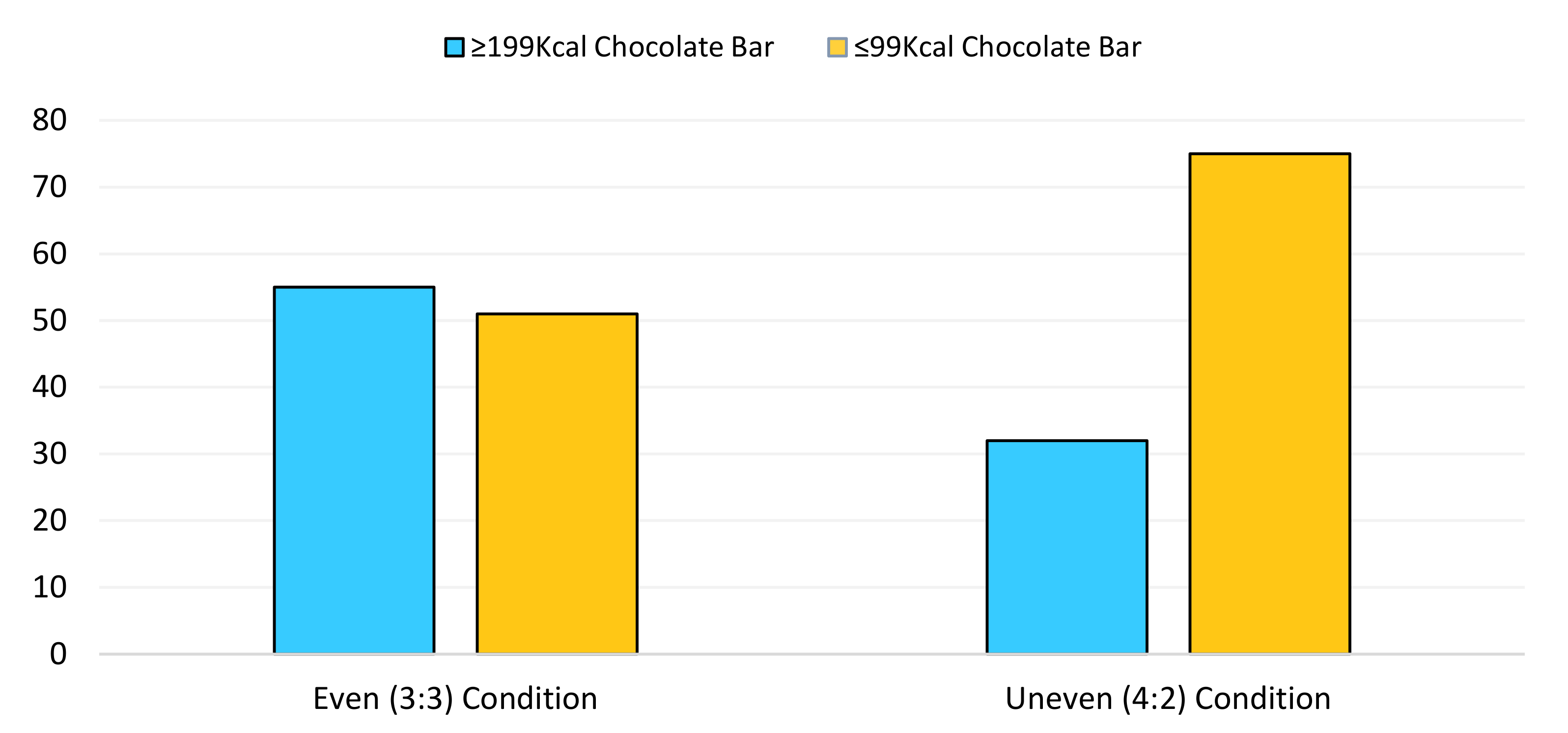

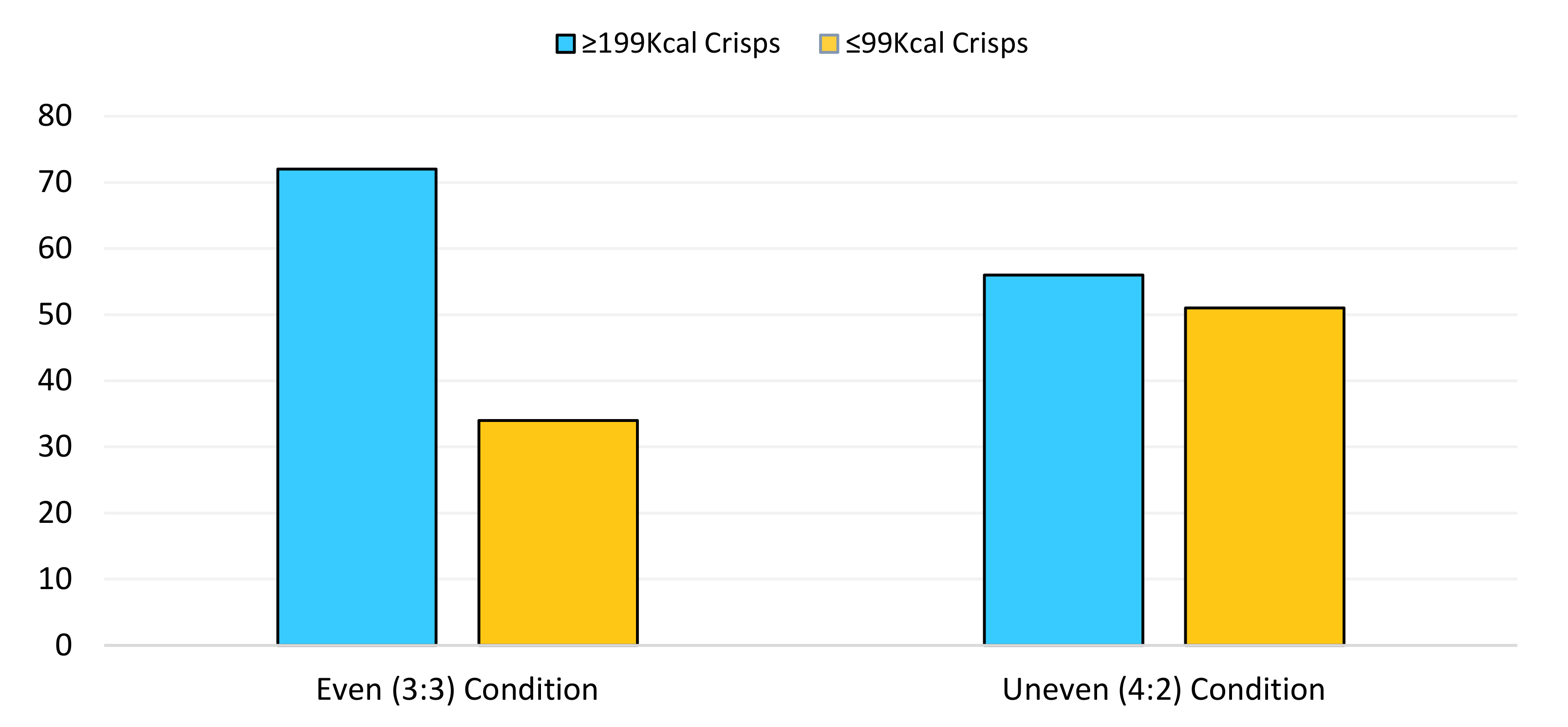

3.3. Effect of Condition on Snack Choice

3.4. Covariates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall, K.D.; Ayuketah, A.; Brychta, R.; Cai, H.; Cassimatis, T.; Chen, K.Y.; Fletcher, L.A. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: An inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Babey, S.H. Contextual influences on eating behaviours: Heuristic processing and dietary choices. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.M.; Reisch, L.A. Behavioural insights and (un) healthy dietary choices: A review of current evidence. J. Consum. Policy 2019, 42, 3–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Cavallo, C. Increasing healthy food choices through nudges: A systematic review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78, 103714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpyn, A.; McCallops, K.; Wolgast, H.; Glanz, K. Improving consumption and purchases of healthier foods in retail environments: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechey, R.; Marteau, T.M. Availability of healthier vs. less healthy food and food choice: An online experiment. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechey, R.; Hollands, G.J.; Carter, P.; Marteau, T.M. Altering the availability of products within physical micro-environments: A conceptual framework. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rung, J.M.; Madden, G.J. Experimental reductions of delay discounting and impulsive choice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2018, 147, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poelman, M.P.; Gillebaart, M.; Schlinkert, C.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Derksen, E.; Mensink, F.; De Vet, E. Eating behavior and food purchases during the COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional study among adults in the Netherlands. Appetite 2020, 157, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, B.C.; Steffen, J.; Schlichtiger, J.; Brunner, S. Altered nutrition behavior during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in young adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLongis, A.; Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, L.; Bergdahl, J.; Nyberg, L.; Nilsson, L.G. Longitudinal analysis of the relation between moderate long-term stress and health. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2007, 23, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M. Life stress and health: A review of conceptual issues and recent findings. Teach. Psychol. 2016, 43, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, D.; Crosnoe, R.; Reczek, C. Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, E.; O’Connor, D.B.; Conner, M. Daily hassles and eating behaviour: The role of cortisol reactivity status. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2007, 32, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J. Impact of Stress Levels on Eating Behaviors among College Students. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.J.; Campbell, I.C.; Troop, N. Increases in weight during chronic stress are partially associated with a switch in food choice towards increased carbohydrate and saturated fat intake. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2014, 22, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, E.J.; Alvarez, D.; Martinez-Velarde, D.; Vidal-Damas, L.; Yuncar-Rojas, K.A.; Julca-Malca, A.; Bernabe-Ortiz, A. Perceived stress and high fat intake: A study in a sample of undergraduate students. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 0192827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, S.J.; Nowson, C.A. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition 2007, 23, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Jones, F.; Conner, M.; McMillan, B.; Ferguson, E. Effects of daily hassles and eating style on eating behavior. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, S20–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, L.E.; Czarnecka, M.; Kitlinska, J.B.; Tilan, J.U.; Kvetňanský, R.; Zukowska, Z. Chronic stress, combined with a high-fat/high-sugar diet, shifts sympathetic signaling toward neuropeptide Y and leads to obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1148, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielmann, A.; Brunner, T.A. Consumers’ snack choices: Current factors contributing to obesity. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandiah, J.; Yake, M.; Jones, J.; Meyer, M. Stress influences appetite and comfort food preferences in college women. Nutr. Res. 2006, 26, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosschot, J.F.; Gerin, W.; Thayer, J.F. The perseverative cognition hypothesis: A review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006, 60, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, S.S.; Kemeny, M.E. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, F.; Prestwich, A.; Caperon, L.; O’Connor, D.B. Perseverative cognition and health behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottaviani, C.; Thayer, J.F.; Verkuil, B.; Lonigro, A.; Medea, B.; Couyoumdjian, A.; Brosschot, J.F. Physiological concomitants of perseverative cognition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottaviani, C. Brain-heart interaction in perseverative cognition. Psychophysiology 2018, 55, 13082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropley, M.; Michalianou, G.; Pravettoni, G.; Millward, L.J. The relation of post-work ruminative thinking with eating behaviour. Stress Health 2012, 28, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querstret, D.; Cropley, M. Assessing treatments used to reduce rumination and/or worry: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 996–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinhoven, P.; Klein, N.; Kennis, M.; Cramer, A.O.; Siegle, G.; Cuijpers, P.; Bockting, C.L. The effects of cognitive-behavior therapy for depression on repetitive negative thinking: A meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018, 106, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarrick, D.J.; Prestwich, A.; Prudenzi, A.; O’Connor, D.B. Health Effects of Psychological Interventions for Worry and Rumination: A Meta-Analysis. 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/bsf9e (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Chaput, J.P.; Sharma, A.M. Is physical activity in weight management more about ‘calories in’ than ‘calories out’? Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1768–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, C.R.; Zeballos, E. Cognitive aids and food choice: Real-time calorie counters reduce calories ordered and correct biases in calorie estimates. Appetite 2019, 141, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccola, P.M.; Dickerson, S.S.; Yim, I.S. Trait and state perseverative cognition and the cortisol awakening response. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, B.L.; Campbell, T.S.; Bacon, S.L.; Gerin, W. The influence of trait and state rumination on cardiovascular recovery from a negative emotional stressor. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 31, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang, M.A.; Sa’at, N.; Bakar, T.M.I.T.A. Sample size guidelines for logistic regression from observational studies with large population: Emphasis on the accuracy between statistics and parameters based on real life clinical data. Malays. J. Med Sci. MJMS 2018, 25, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calorie Reduction: The Scope and Ambition for Action; Public Health England: London, UK, 2018.

- Change for Life. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/change4life/food-facts/healthier-snacks-for-kids (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- YouGov (Chocolate). Available online: https://yougov.co.uk/ratings/food/fame/confectionaries/all (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- YouGov (Snacks). Available online: https://yougov.co.uk/ratings/food/fame/food-snack-brands/all (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Ehring, T.; Zetsche, U.; Weidacker, K.; Wahl, K.; Schönfeld, S.; Ehlers, A. The Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ): Validation of a content-independent measure of repetitive negative thinking. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2011, 42, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, I.; Mor, N.; Chiorri, C.; Koster, E.H. The brief state rumination inventory (BSRI): Validation and psychometric evaluation. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2018, 42, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, F.; Prestwich, A.; Ferguson, E.; O’Connor, D.B. Cross-sectional and prospective associations between stress, perseverative cognition and health behaviours. Psychol. Health 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, K.E.; Park, C.L.; Laurenceau, J.P. A daily diary study of rumination and health behaviors: Modeling moderators and mediators. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesla, J.; Dickson, K.S.; Anderson, N.L.; Neal, D.J. Negative repetitive thought and college drinking: Angry rumination, depressive rumination, co-rumination, and worry. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2011, 35, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willem, L.; Bijttebier, P.; Claes, L.; Raes, F. Rumination subtypes in relation to problematic substance use in adolescence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breithaupt, L.; Rallis, B.; Mehlenbeck, R.; Kleiman, E. Rumination and self-control interact to predict bulimic symptomatology in college students. Eat. Behav. 2016, 22, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.A.; Ainette, M.G.; Stoolmiller, M.; Gibbons, F.X.; Shinar, O. Good self-control as a buffering agent for adolescent substance use: An investigation in early adolescence with time-varying covariates. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2008, 22, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, C.; Schreck, C.J.; Miller, J.M. Binge drinking and negative alcohol-related behaviors: A test of self-control theory. J. Crim. Justice 2004, 32, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.M.; Mason, T.B.; Cao, L.; Goldschmidt, A.B.; Lavender, J.M.; Crosby, R.D.; Peterson, C.B. A test of a state-based, self-control theory of binge eating in adults with obesity. Eat. Disord. 2018, 26, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornacka, M.; Czepczor-Bernat, K.; Napieralski, P.; Brytek-Matera, A. Rumination, mood, and maladaptive eating behaviors in overweight and healthy populations. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2020, 26, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gov. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/plans-to-cut-excess-calorie-consumption-unveiled (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Hagan, K.E.; Alasmar, A.; Exum, A.; Chinn, B.; Forbush, K.T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of attentional bias toward food in individuals with overweight and obesity. Appetite 2020, 151, 104710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favieri, F.; Forte, G.; Casagrande, M. The executive functions in overweight and obesity: A systematic review of neuropsychological cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J.F.; Lane, R.D. Perseverative thinking and health: Neurovisceral concomitants. Psychol. Health 2002, 17, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, M.; Boncompagni, I.; Forte, G.; Guarino, A.; Favieri, F. Emotion and overeating behavior: Effects of alexithymia and emotional regulation on overweight and obesity. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2020, 25, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, A.E.; Lee, M.; Price, M.; Williams, C. A serial mediation model of the relationship between alexithymia and BMI: The role of negative affect, negative urgency and emotional eating. Appetite 2019, 133, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechey, R.; Jenkins, H.; Cartwright, E.; Marteau, T.M. Altering the availability of healthier vs. less healthy items in UK hospital vending machines: A multiple treatment reversal design. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, S.; Berger, N.; Cornelsen, L.; Eling, J.; Er, V.; Greener, R.; Yau, A. COVID-19: Impact on the urban food retail system and dietary inequalities in the UK. Cities Health 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajbich, I.; Hare, T.; Bartling, B.; Morishima, Y.; Fehr, E. A common mechanism underlying food choice and social decisions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, 1004371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Pollard, T.M.; Wardle, J. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: The food choice questionnaire. Appetite 1995, 25, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, J.E.; Finlayson, G.; Gibbons, C.; Caudwell, P.; Hopkins, M. The biology of appetite control: Do resting metabolic rate and fat-free mass drive energy intake? Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Even Condition (N = 105) | Uneven Condition (N = 107) | Overall (N = 212) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | N | 105 | 106 | 211 |

| Mean | 29.77 | 29.65 | 29.71 | |

| SE mean | 1.14 | 1.04 | 0.77 | |

| Sex | Females | 66 (62.9%) | 73 (68.2%) | 139 (65.6%) |

| Males | 39 (37.1%) | 34 (31.8%) | 73 (34.4%) | |

| BMI | N | 92 | 103 | 195 |

| Mean | 24.16 | 24.19 | 24.18 | |

| SE mean | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.4 | |

| Stress | N | 105 | 107 | 212 |

| Mean | 51.5 | 42.45 | 46.93 | |

| SE mean | 2.82 | 2.79 | 2.08 | |

| Hunger | N | 105 | 107 | 212 |

| Mean | 40.57 | 36.42 | 38.48 | |

| SE mean | 2.82 | 2.71 | 1.96 | |

| State Rumination | N | 105 | 107 | 212 |

| Mean | 351.69 | 309.65 | 330.47 | |

| SE mean | 21.72 | 19.05 | 14.46 | |

| Trait Preservative Cognition | N | 105 | 107 | 212 |

| Mean | 34.4 | 31.32 | 32.84 | |

| SE mean | 1.22 | 1.14 | 0.84 | |

| Health Status | Poor | 4 (3.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 5 (2.4%) |

| Fair | 18 (17.1%) | 10 (9.3%) | 28 (13.2%) | |

| Good | 34 (32.4%) | 42 (39.3%) | 76 (35.8%) | |

| Very Good | 35 (33.3%) | 37 (34.6%) | 72 (34.0%) | |

| Excellent | 14 (13.3%) | 17 (15.9%) | 31 (14.6%) | |

| Weekly | ≤14 Units a week | 45 (42.9%) | 43 (40.2%) | 88 (41.5%) |

| Alcohol | ≥15 Units a week | 50 (47.6%) | 56 (52.3%) | 106 (50.0%) |

| Consumption | Do not drink | 10 (9.5%) | 8 (7.5%) | 18 (8.5%) |

| Smoking Status | Non-smoker | 71 (67.4%) | 84 (78.5%) | 155 (73.1%) |

| Smoker | 12 (11.5%) | 10 (9.3%) | 22 (10.4%) | |

| Occasional Smoker | 2 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.9%) | |

| Quitting (currently) | 20 (19.0%) | 13 (12.1%) | 33 (15.6%) | |

| Relationship Status | Single, never married | 55 (52.4%) | 65 (56%) | 120 (56.6%) |

| Married | 30 (28.6%) | 20 (18.7%) | 50 (23.6%) | |

| Separated | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (1.4%) | |

| Living with partner | 18 (17.1%) | 19 (17.8%) | 37 (17.5%) | |

| Widowed/Divorced | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (0.9%) | |

| Household Income | £0–£14,000 | 30 (28.6%) | 38 (35.5%) | 68 (32.1%) |

| £14,001–£24,000 | 21 (20.0%) | 10 (9.3%) | 31 (14.6%) | |

| £24,001–£30,000 | 13 (12.4%) | 15 (14.0%) | 28 (13.2%) | |

| £30,001–£40,000 | 9 (8.5%) | 13 (12.1%) | 22 (10.4%) | |

| £40,001–£80,000 | 22 (21.0%) | 22 (20.6%) | 44 (20.8%) | |

| £80,001+ | 10 (9.5%) | 9 (8.4%) | 19 (8.9%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eschle, T.M.; McCarrick, D. Perseverative Cognition and Snack Choice: An Online Pilot Investigation. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11030033

Eschle TM, McCarrick D. Perseverative Cognition and Snack Choice: An Online Pilot Investigation. Behavioral Sciences. 2021; 11(3):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11030033

Chicago/Turabian StyleEschle, Timothy M., and Dane McCarrick. 2021. "Perseverative Cognition and Snack Choice: An Online Pilot Investigation" Behavioral Sciences 11, no. 3: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11030033

APA StyleEschle, T. M., & McCarrick, D. (2021). Perseverative Cognition and Snack Choice: An Online Pilot Investigation. Behavioral Sciences, 11(3), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11030033