1. Introduction

In 1870, the

Instituto Geográfico, the precursor of the current

Instituto Geográfico Nacional (IGN), was established by Royal Decree on 12 September 1870 [

1]. Among its assigned tasks was the creation of a geodetic network covering the entire Spanish territory, along with all the topographic operations required for the preparation of the National Topographic Map at a 1:50,000 scale.

The geodetic work had already been planned in 1853, proposing the observation of a geodetic triangulation network consisting of three chains of triangles in the direction of the parallels, four chains of triangles in the direction of the meridians, and three chains of triangles along the coastlines (

Figure 1). The measurements began in 1854, and in 1858, the central base of the first-order geodetic triangulation was measured in Madridejos (province of Toledo), using a bimetallic ruler made of platinum and brass that was specifically designed and constructed for this purpose (

Figure 2a). The

Instituto Geográfico later published a manual [

2], in which clear instructions were provided for carrying out geodetic works. This manual included procedures for the establishment and measurement of a first-order geodetic network, covering the definition of geodetic bases, the selection and preparation of triangulation marks, and the azimuthal and zenithal observations of the network. It also detailed the implementation of a precision levelling network, including the determination of mean sea level using tide gauges (

Figure 2b). Finally, it outlined procedures for densifying the network with second- and third-order triangulation.

These geodetic operations provided the foundation for the parallel development of topographic works in all Spanish municipalities, which began in 1871. The corresponding instructions were prepared according to the operational plan of the

Instituto Geográfico, approved on 30 September 1870, and signed by its director, General Ibáñez Ibero [

3]. A second manual was subsequently published [

4], offering detailed guidelines for conducting these topographic surveys. This document defined the procedures for triangulation, boundary marker placement, the planimetric representation of topographic features, the depiction of isolated buildings, special elements and agricultural areas, the mapping of population centres with more than ten buildings, and the representation of terrain relief.

Among these tasks, particular importance was given to the determination of boundary lines between municipalities and their neighbours. This process began with the placement or survey of boundary markers, carried out with the assistance of the respective City Council, and the drafting of the corresponding demarcation agreement. The topographical instruction manual [

4] also included protocols for resolving disputes or lack of agreement. Once the placement or survey of markers was completed, the plan of the boundary lines was drawn by conducting topographic itineraries with topographic compasses (

Figure 2c) and measuring distances with tape or grade rod. Measurements were recorded using a standardized form designed for this purpose (

Figure 3).

For operations involving the compass, it was mandatory to determine the declination of each observer’s compass prior to the start of fieldwork and to recheck this declination weekly. Additionally, observers were instructed to avoid carrying iron objects within 20 m of the compass during observations, to prevent interference with the magnetic needle.

The declination values were recorded at the beginning of each fieldwork notebook, thus providing an interesting source of magnetic declination data corresponding to the time of observation. In this study, we use the values recorded in the fieldwork notebooks to analyse the Earth’s magnetic field throughout the declination data at the time these values were recorded.

Given that these declination data have never been used before in the context of Earth’s magnetic field analysis, this study will consider them for the first time as a source of data that can be validated for conducting geomagnetic studies in past eras.

The following section describes the methodology used to extract declination data from a selected set of fieldwork notebooks, followed by a comparison of the resulting dataset with two independent sources of declination data (Results and Discussion).

2. Data

As a result of the work carried out for the preparation of the National Topographic Map at a 1:50,000 scale, a very large volume of documentation was generated from fieldwork conducted across all the municipalities of Spain (more than 8000 municipalities). All this documentation is currently preserved in the Topographic Archive of the IGN. The collection of fieldwork notebooks is extensive and includes, among others, the following types: triangulations, baseline measurements, levelling lines, municipal planimetries, boundary line statements, topographic itineraries made using topographic compasses (including boundary lines), and compass declination measurements.

These compass declination measurements (see

Figure 4 for an example of a measurement declination sheet) represent a potentially valuable source for obtaining historical declination values. However, this type of documentation is not scanned yet, and its retrieval within the archive is particularly complex.

In the fieldwork notebooks of topographic itineraries conducted with a topographic compass, the cover page usually includes information such as the compass used, its declination, the name of the observer, the date (either the date when the document was incorporated into the archive, the date of the survey, or both), and the municipalities surveyed, especially if the notebook corresponds to a boundary line. This information is available for each municipality and is relatively easy to locate in the Topographic Archive of the IGN.

Moreover, the Geographical Documentation and Library Service of the IGN has undertaken significant efforts to scan the holdings of the Topographic Archive. Documentation related to municipal boundaries, including boundary line statements and fieldwork notebooks created since the beginning of field operations in 1871, has been scanned and made available to the public through the IGN’s website:

https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/actas-cuadernos-resenas-graficos-lineas-limite (accessed on 27 November 2025).

Notebooks created prior to the publication of the form shown in

Figure 3 usually list the municipalities surveyed on the cover page, but only a few include the model and serial number of the compass used. It is generally possible to find, either on the cover (

Figure 5a) or inside the notebook, the compass declination. However, the date of the survey is recorded irregularly, sometimes with the exact day, sometimes only the month, or just the year. After the publication of the standardised form by 1878, the cover pages of the fieldwork notebooks became uniform (

Figure 5b), making it easier to locate the survey data. In addition, these notebooks are always signed by the operator and the supervisor, and the date of the survey is clearly indicated.

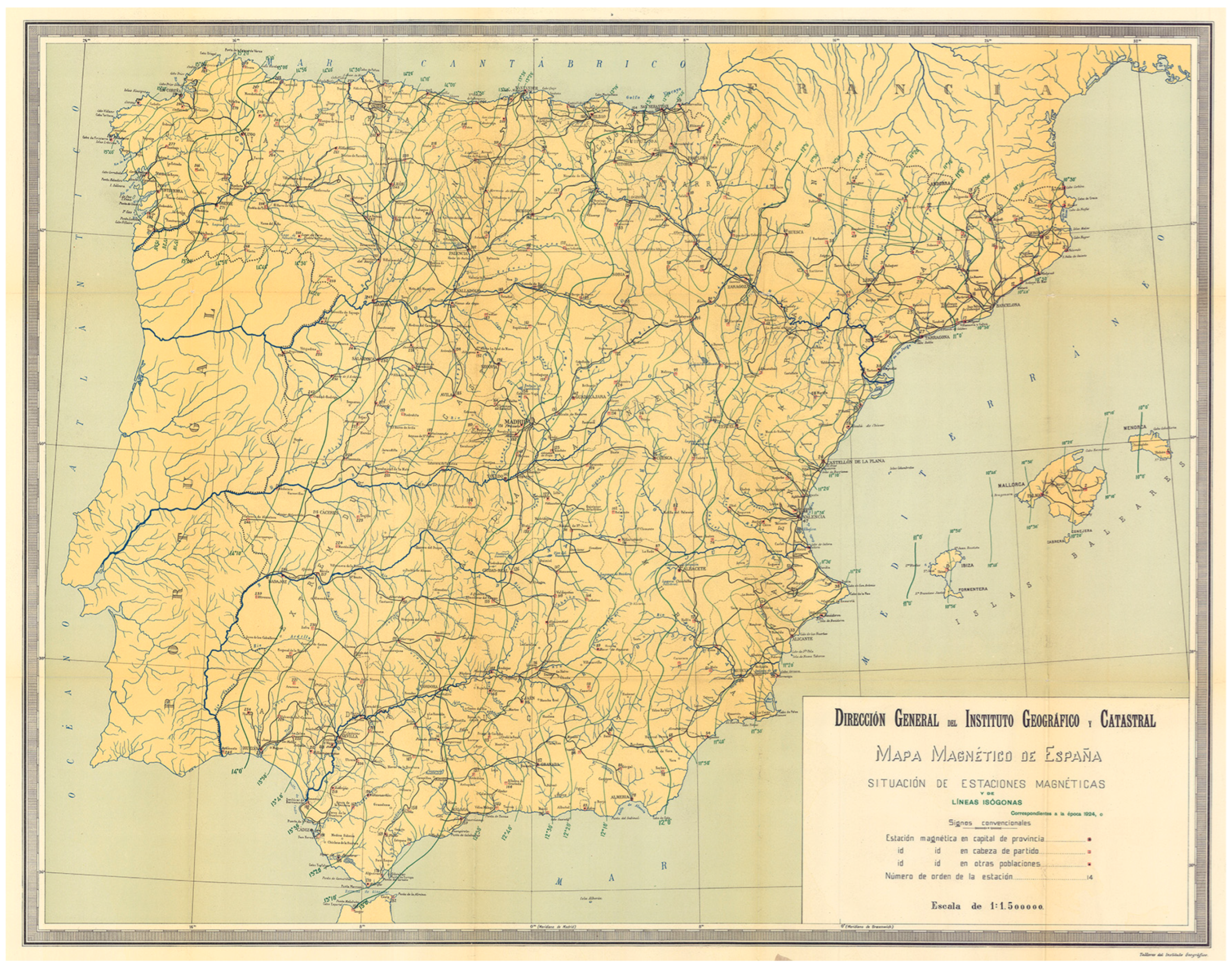

In addition to the declination data derived from field notebooks, we use two additional and independent sources of data to compare them with this compiled declination dataset. The first consists of declination values generated using the COV-OBS.x2 model [

5]. The COV-OBS.x2 main geomagnetic field model is based on a combination of data sources and provides a highly accurate physical-mathematical representation of the spatial and temporal variations of the geomagnetic main field. These data sources include ground-based observatories, satellite measurements, and historical records, covering the period from 1840 to 2020. The second source comprises historical measurements obtained from the declination chart for the epoch 1 January 1924 (1924.0) produced by the IGN. In 1904, the

Instituto Geográfico was the first institution in Spain to undertake the development of a national magnetic map. The original project was highly ambitious, aiming to survey 500 stations evenly distributed across the territory, with an average spacing of 35 km between them [

6]. The measurements were carried out between 1912 and 1919, but due to budgetary constraints, only 286 stations were eventually surveyed. At these sites, the three magnetic elements—Declination (D), Inclination (I), and Horizontal Intensity (H)—were measured. The resulting values were subsequently reduced to the epoch 1924.0 using the secular variation determined at a selection of stations measured annually: the secular variation obtained at Ebro Observatory (IAGA code EBR) and that obtained from comparisons with the values determined by Lamont in 1858 [

7] and Moureaux in 1888 [

8]. As a result, they produced and published the Magnetic Map of Spain for the epoch 1924.0 [

9]. This map is composed of three charts: Declination (see

Figure 6), Inclination, and Horizontal Intensity.

3. Methodology

A preliminary test of the data quality available in the boundary line fieldwork notebooks was carried out using declination values from 1871. The results, presented in [

10], confirmed the reliability of these declination data and served as the starting point for this broader study on geomagnetic declination in mainland Spain.

Given the large number of municipalities in Spain (8131 according to

Nomenclátor of the IGN, the official gazetteer of municipalities of Spain:

https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/nomenclator-geografico-municipios-entidades-poblacion, accessed on 27 November 2025) and the existence of multiple boundary lines for each one, the number of fieldwork notebooks available through the IGN website exceeds 50,000. This makes a comprehensive review of all available documents unfeasible for extracting the noted declination values. Consequently, a selection was made by choosing a reasonable number of evenly distributed municipalities to represent the Spanish mainland.

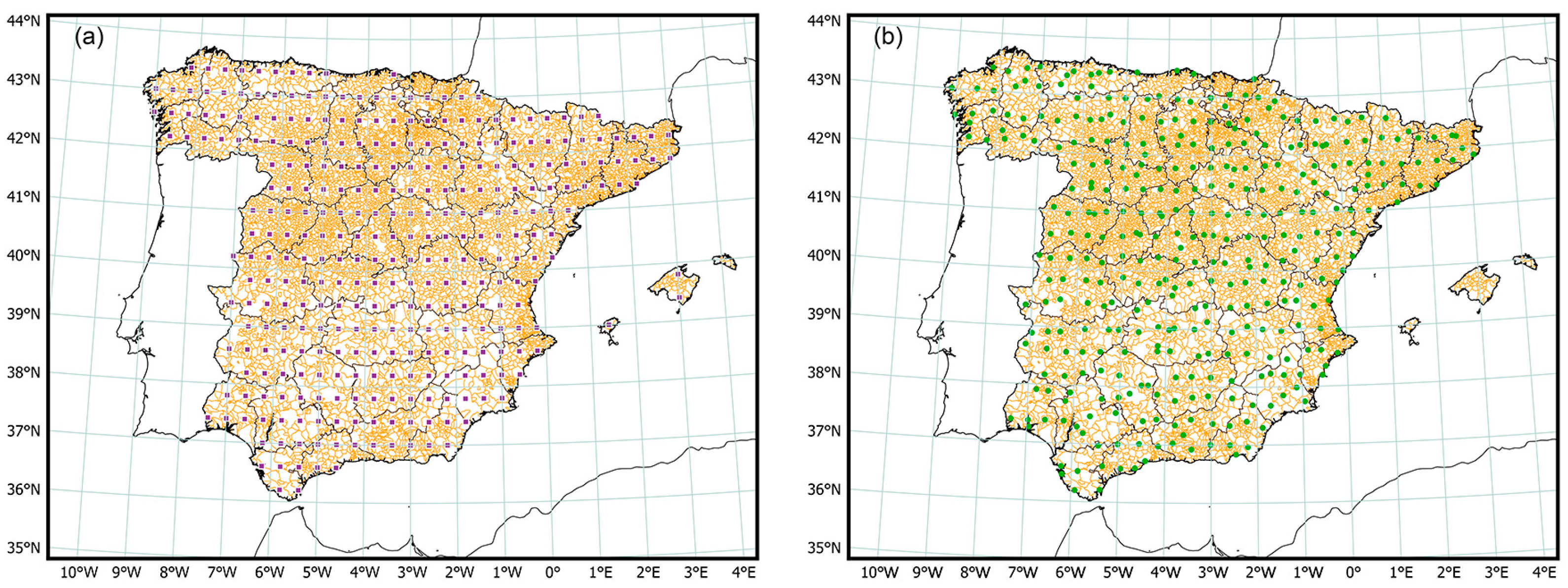

Using QGIS software (

https://qgis.org/, accessed on 27 November 2025), we created a project incorporating the layers of provinces and municipalities of Spain, obtained from the Spanish Database of Administrative Borders maintained by the IGN. Over these layers (available at

https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/limites-municipales-provinciales-autonomicos, accessed on 27 November 2025), we generated a grid of equidistant points with a spacing of 0.40° × 0.40°, covering the Spanish mainland between 43.80° N, 9.00° W and 35.80° N, 3.40° E. Intersecting these grid points with the municipal layer yielded a list of 323 points corresponding to municipalities evenly distributed across the mainland (see

Figure 7a).

This grid has been redistributed, referring to the geographical coordinates associated with each municipality selected. In this sense, we obtained the geographical coordinates (latitude, longitude, and altitude) for each selected municipality, using the

Nomenclátor of Municipalities and Population Entities published by the IGN. Then, we obtained a new location for each point of the grid, which were associated with the geographical coordinates provided by the

Nomenclátor for each municipality whose new distribution is shown in

Figure 7b. In small municipalities, the displacement is short, but in large municipalities, the new points may have moved an appreciable distance.

For each selected municipality, multiple fieldwork notebooks are available, one for each boundary line shared with neighbouring municipalities, including revisions or modifications conducted over time. For consistency, we selected, for each municipality, the oldest fieldwork notebook that contained a recorded declination value.

From these fieldwork notebooks, we extracted the following information:

Notebook number.

Date of survey.

Province.

Municipality.

Neighbouring municipality.

Serial number of the compass (if available).

Compass model (if available).

Compass declination.

In addition to the municipalities selected through the grid, we also reviewed the fieldwork notebooks corresponding to provincial capitals not included in the grid selection. We have also eliminated three data situated in the Balearic Islands, considering only data from mainland Spain. As a result, we compiled a final dataset comprising 358 municipalities, for which all the aforementioned parameters were gathered (see

Figure 7b).

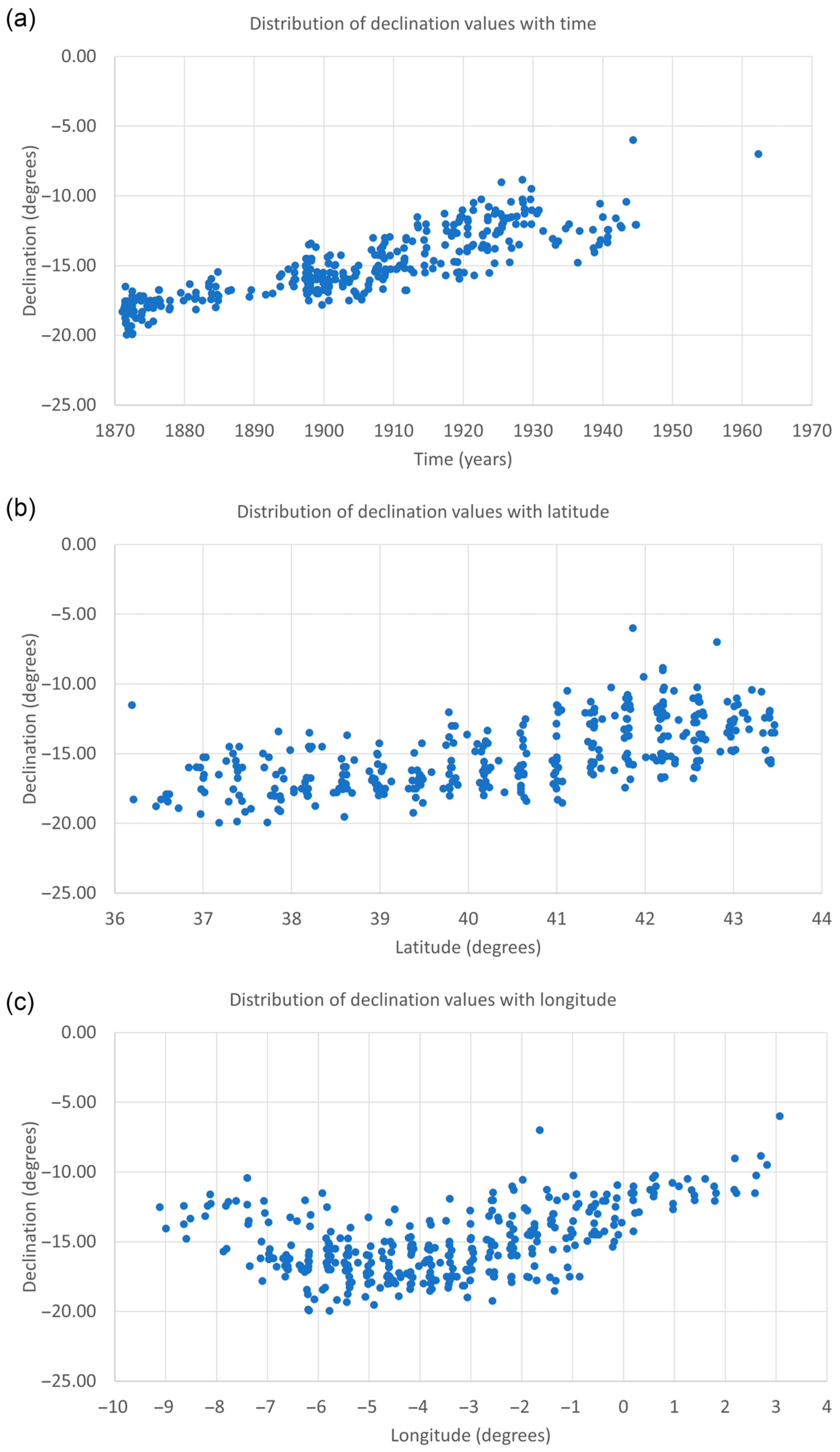

4. Results

After evaluating the 358 fieldwork notebooks corresponding to each location plotted in

Figure 7b, we extracted the declination data, which are compiled in

Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials. From this declination dataset, we obtained a compilation of declination records spanning a long temporal range. These data begin in 1871 and extend into the 1940s, with a single exception from 1962 (see

Figure 8a). This extended time frame reflects the significant effort and resources required by the IGN to complete the boundary line survey work. The spatial distribution of the declination values with respect to latitude (

Figure 8b) and longitude (

Figure 8c) follows the pattern imposed by the selection grid used in our sampling process, covering properly all of peninsular Spain.

As the declination values recorded in the fieldwork notebooks represent the total geomagnetic internal field, we applied a correction to mitigate the influence of the crustal field. This adjustment allowed us to isolate the main geomagnetic field, enabling a direct comparison with contemporary geomagnetic main field models.

To estimate the crustal field, we used the Geomagnetic Reference Model for the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands, also known as the Geomagnetic Iberian Model [

11]. Declination values corresponding to the crustal field were extracted from this model at the mapping stations used in its development. These values were then interpolated to the coordinates of each data point in our dataset.

Although these crustal field values are referenced to epoch 2020.0, the crustal field is considered temporally invariant, and thus the correction was applied uniformly. The resulting main field declination values are included in

Table S2 of the Supplementary Materials. It is important to note that the crustal field is not fully removed from the original declination measurements, as the local contributions (also referred to as crustal anomaly biases) are not entirely accounted for in the cited Spanish reference model. Consequently, the final declination data remain contaminated by a portion of these anomaly biases that were not eliminated in the preceding processing steps.

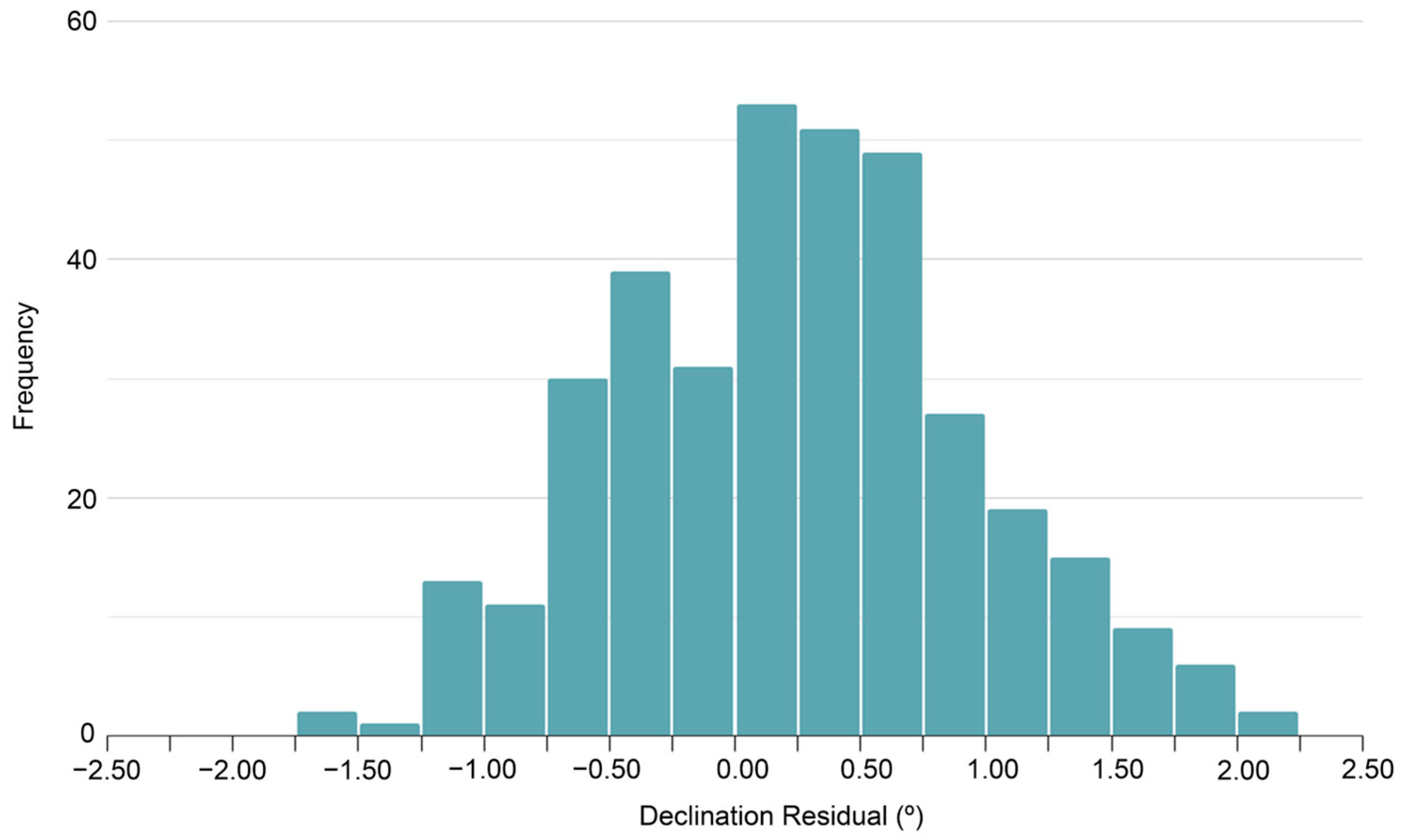

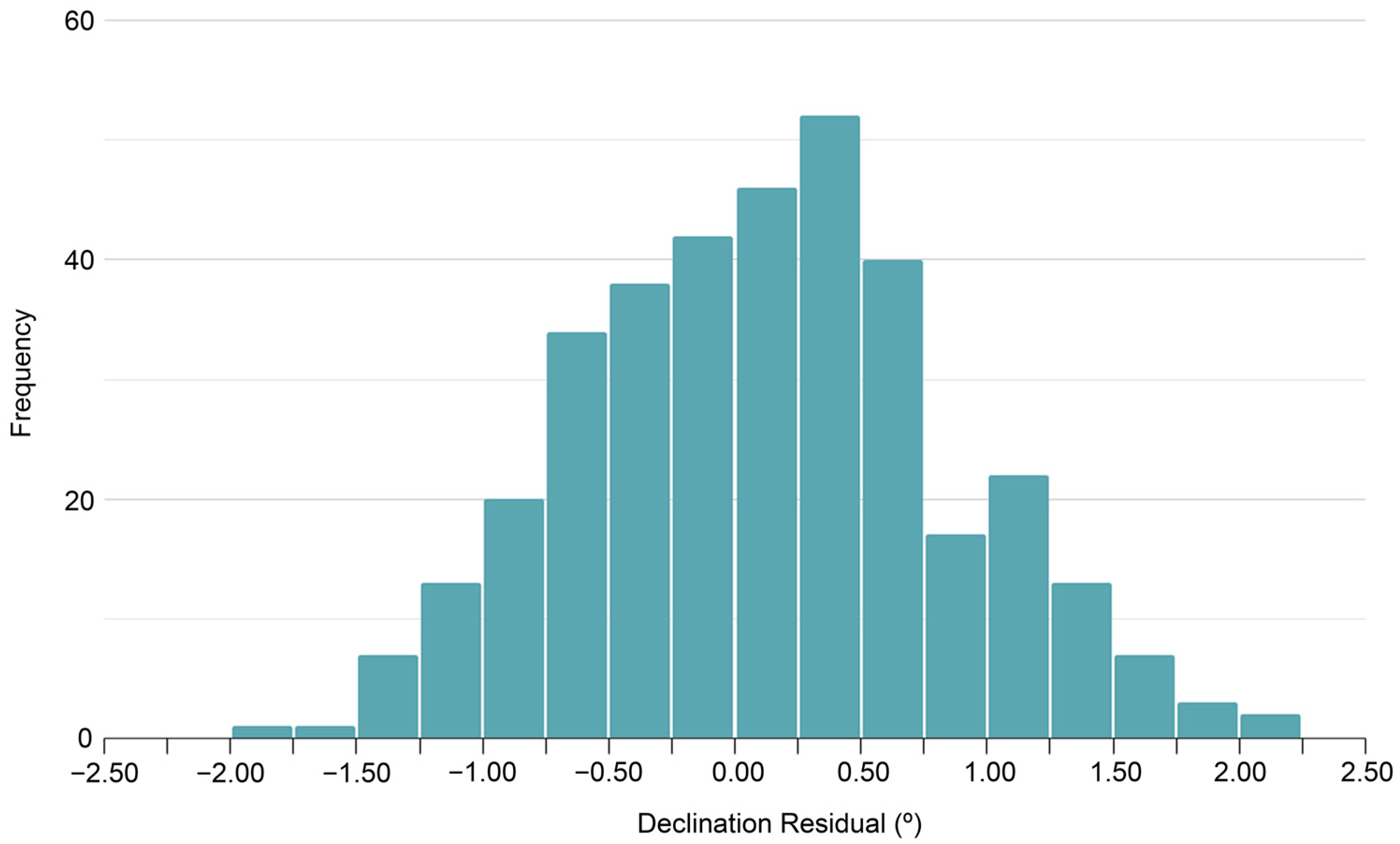

Using the coordinates and dates of each observation, we computed the expected main field declination at each site using the COV-OBS.x2 model [

5]. We then subtracted these modelled values from the corrected declinations, yielding residuals for each location. The distribution of these residuals is shown in

Figure 9 and follows a normal distribution with a mean and standard deviation equal to 0.24° and 0.72°, respectively.

To assess the quality of the recovered dataset, we compare the main field declination values extracted from the fieldwork notebooks with those provided by the COV-OBS.x2 model by plotting both datasets on a map. Since the recovered declination dataset spans several decades, we translated all main field declination values to a common epoch. The median year of the dataset is 1903, and we rounded to epoch 1900.0 for uniform representation and analysis.

To transfer the declination values to epoch 1900.0, we use the temporal gradient given by the COV-OBS.x2 model. For each observation point, we computed the difference in declination between the original observation date and the target epoch (1900.0). This gradient was subtracted from the main field value at the original date to obtain the transferred value.

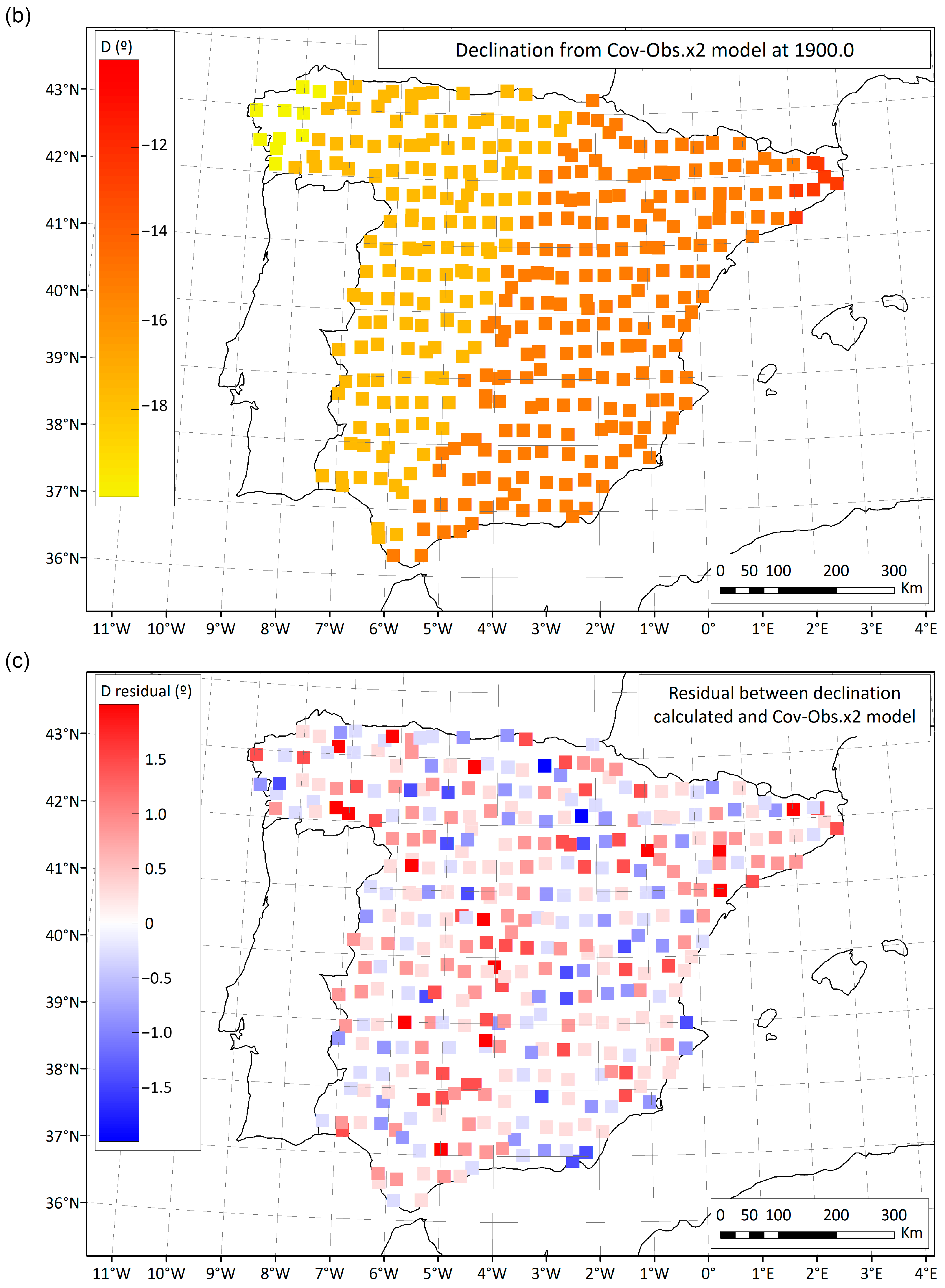

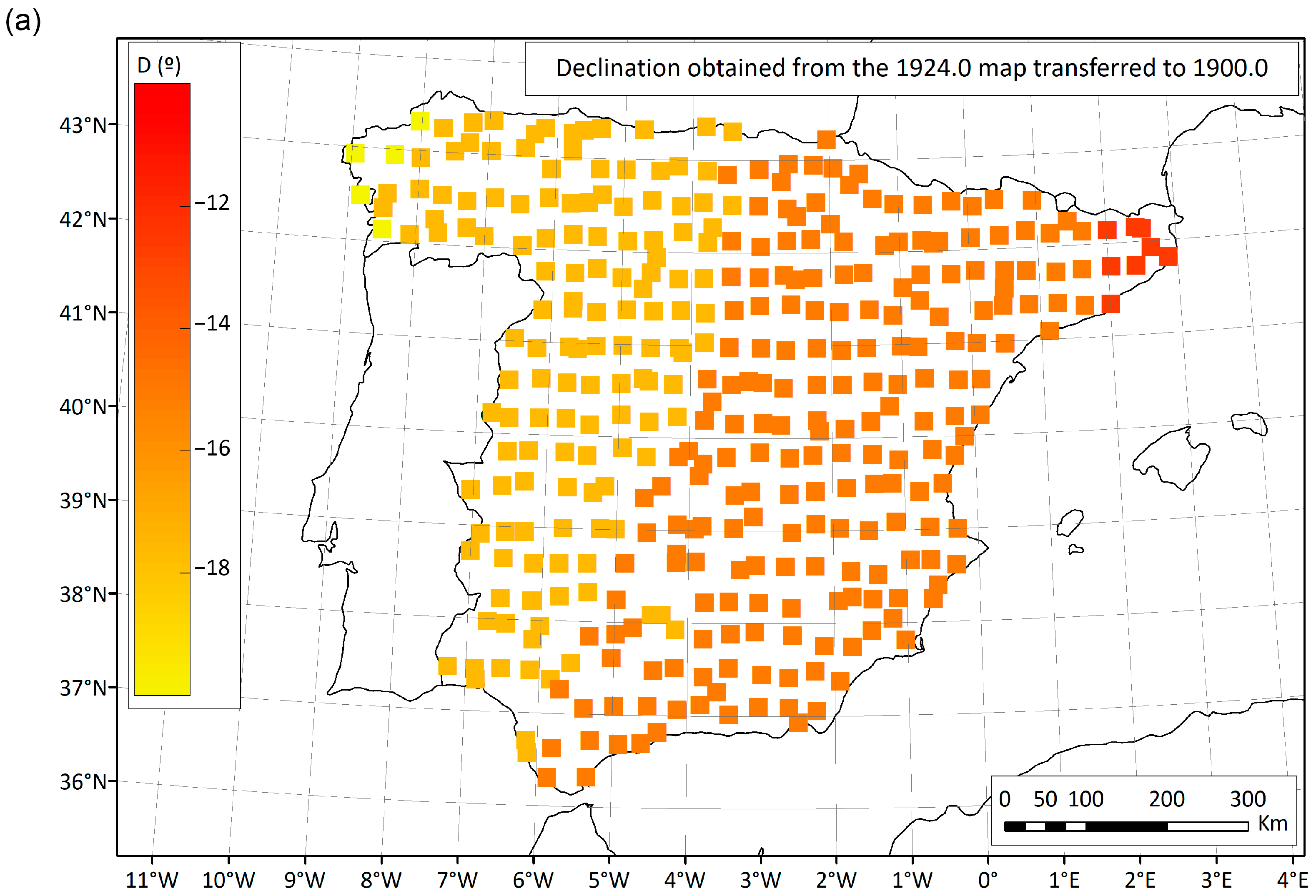

These epoch-corrected values, provided in

Table S3 of the Supplementary Materials, were plotted on a map to show the spatial distribution of declination over mainland Spain at epoch 1900.0. The results include the following: (a) declination values derived from the historical fieldwork notebooks (

Figure 10a), (b) model-predicted declination values at the same locations and epoch from COV-OBS.x2 (

Figure 10b), and (c) the residuals between the measured and modelled declinations (

Figure 10c). Both the historical compiled data and the values from the geomagnetic model show a clear longitudinal dependence of the magnetic declination, with values ranging from 10° W to 20° W as we move from east to west across the Iberian Peninsula. The residual map (with values ranging from −1.5° to +1.5°) does not reveal a clear pattern, indicating that the differences between the historical data and the model values are randomly distributed across the peninsular territory. However, as mentioned before, the declination values derived from the fieldwork notebooks could still reflect a significant contribution from the crustal field (anomaly biases), so these residuals could also show crustal declination anomalies (taking into account that the COV-OBS.x2 model data do not contain information on the crustal field).

The same methodology has been applied over the declination values obtained for the Magnetic Map of Spain of 1924.0. The original declination data coming from this magnetic map [

9] have been compiled in

Table S4 of the Supplementary Materials. Before comparing these data with our database, the crustal field was calculated from the Geomagnetic Iberian Model [

11] and then subtracted to the original values to obtain the main field in these points. Subsequently, all these main field values were transferred to the epoch 1900.0 using the same methodology detailed before. The declination values from the Magnetic Map of 1924.0 were then spatially interpolated to the 358 locations corresponding to our recovered declination dataset.

These interpolated values have been subtracted from the main field declination values derived from the historical fieldwork notebooks, obtaining the residual for each location. The distribution of these residuals, shown in

Figure 11, follows a normal distribution with a mean and standard deviation equal to 0.12° and 0.73°, respectively.

The results, provided in

Table S5 of the Supplementary Materials, were plotted again on a map to show the spatial distribution of these values over mainland Spain at 1900.0, including the following: (a) declination values derived from the 1924.0 map (

Figure 12a), and (b) the residuals between the declination values derived from the historical fieldwork notebooks and the values derived from the 1924.0 map (

Figure 12b).

Once again, the comparison between the historical compiled data (

Figure 10a) and the values derived from the 1924.0 map (

Figure 12a) shows a clear longitudinal dependence of the magnetic declination, with values ranging from 10° W to 20° W. The residual map (

Figure 12b), with values also ranging from −1.5° to +1.5°, does not reveal a clear pattern either, again showing a random distribution throughout the peninsular territory (as in the map of

Figure 10c, these residuals also reflect the contribution from the crustal field in the locations where the declination measurements noted in the fieldwork notebooks were taken, i.e., the anomaly biases of the original declination dataset).

5. Conclusions

The fieldwork carried out by the Instituto Geográfico Nacional (IGN) since 1871, aimed at producing the National Topographic Map of Spain at a scale of 1:50,000, required a substantial investment of both human and economic resources over nearly a century.

All documentation generated throughout the execution of this extensive project has been preserved by the IGN. These legacy data, of great historical and scientific value, continue to provide meaningful insights today, as demonstrated by the analyses presented in this study.

From the documentation related to the delimitation of municipal boundaries, we extracted geomagnetic declination values obtained by declining the topographic compasses used during field surveys. After correcting these measurements for the contribution of the crustal field, we constructed a declination map referenced to epoch 1900.0. This map was then compared with the geomagnetic model COV-OBS.x2.

Despite the limited precision of the topographic compasses employed (e.g., devices not specifically designed for high-accuracy geomagnetic work), the residuals obtained show a dispersion generally within ±2°. Nevertheless, the results are sufficiently robust to confirm the usefulness of these historical data. They represent a valuable source of information that can be effectively integrated into geomagnetic research and long-term studies of the Earth’s magnetic field.

To further validate the data obtained, we have used the declination data measured to elaborate the Magnetic Map of Spain for the epoch 1924.0, the first map which represents the magnetic field over the national territory. With these data, corrected for the contribution of the crustal field, we have constructed a declination map referenced to epoch 1900.0 that is comparable to the map obtained from the delimitation of municipal boundaries, showing a good fit. As expected, the declination map for 1900.0 prepared with the 1924.0 data shows better results when compared with the COV-OBS.x2 model, since it is derived from precise measurements of the magnetic field, carried out with appropriate instrumentation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/geosciences15120465/s1: Table S1: Data consulted in the IGN boundary line observation fieldwork notebooks, ordered by provinces, and the coordinates of each municipality obtained from the

Nomenclátor of Municipalities and Population Entities of IGN; Table S2: Declination data obtained from the boundary line notebooks, crustal corrections, and the declination of main field for each point; Table S3: Main field declination data from fieldwork notebooks, their correction to the common epoch 1900.0 using the COV-OBS.x2 model, the declination of the main field in 1900.0, and the residual between declinations provided by the COV-OBS.x2 model and the declinations of the main field in 1900.0; Table S4: Transcription of the measurements of the magnetic elements Declination (D), Inclination (I), and Horizontal component (H) made for the

Mapa Magnético de España para la época 1924.0 and reduced to epoch 1924.0; Table S5: Main field declination data from fieldwork notebooks transferred to the common epoch 1900.0, main field declination data obtained from the interpolation of the 1924.0 declination values previously transferred to 1900.0, and the residual between them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.T. and F.J.P.-C.; methodology, F.J.P.-C.; software, F.J.P.-C.; validation, J.M.T. and F.J.P.-C.; formal analysis, J.M.T. and F.J.P.-C.; investigation, J.M.T.; resources, J.M.T. and E.C.; data curation, J.M.T. and A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.T.; writing—review and editing, F.J.P.-C., A.N., M.L.-M., E.C. and A.B.A.; visualization, J.M.T., A.N., M.L.-M. and F.J.P.-C.; supervision, F.J.P.-C. and A.B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data from the fieldwork notebooks presented in the study are openly available in

https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/actas-cuadernos-resenas-graficos-lineas-limite, accessed on 27 November 2025. The dataset obtained from these fieldwork notebooks is provided in the Supplement. The original data from the measurements taken for the

Mapa Magnético de España para la época 1924.0 presented in the study are published in [

9] and have been transcribed in the Supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude and admiration to the professionals who carried out these enormous projects of observation and representation of the Earth, in often difficult conditions, but with unbeatable professionalism. They also thank the IGN for its great effort to preserve and disseminate this information, which constitutes a priceless legacy and allows studies such as the one presented here. The authors would also like to thank the editor and the four anonymous reviewers for helping us improve the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript (

Note: The current

Instituto Geográfico Nacional (IGN) has had different names throughout its history:

Instituto Geográfico y Estadístico, Instituto Geográfico y Catastral, Instituto Geográfico Catastral y Estadístico. In this text, we have referred to the previous names as

Instituto Geográfico, to make it easier to read):

| IGN | Instituto Geográfico Nacional |

References

- Gaceta de Madrid, 1870. Año CCIX, Num. 257, Miércoles 14 de Septiembre de 1870. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_gazeta/comun/pdf.php?p=1870/09/14/pdfs/GMD-1870-257.pdf&do=1 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Instituto Geográfico y Estadístico. Instrucciones Para los Trabajos Geodésicos; Instituto Geográfico y Estadístico: Madrid, Spain, 1878. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, C. Instrucciones del General Ibáñez de 20 de octubre de 1870; Original manuscript preserved in the IGN library; Instituto Geográfico y Estadístico: Madrid, Spain, 1870; Available online: http://www.ign.es/web/biblioteca_cartoteca/abnetcl.cgi?TITN=10501 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Instituto Geográfico y Estadístico. Instrucciones Para los Trabajos Topográficos; Instituto Geográfico y Estadístico: Madrid, Spain, 1878. [Google Scholar]

- Huder, L.; Gillet, N.; Finlay, C.C.; Hammer, M.D.; Tchoungui, H. COV-OBS. x2: 180 years of geomagnetic field evolution from ground-based and satellite observations. Earth Planets Space 2020, 72, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azpiazu, U.; Gil, R. Magnetismo Terrestre. Su Estudio en España; Instituto Geográfico y Catastral: Madrid, Spain, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, J. Untersuchungen Über die Richtung und Stärke des Erdmagnetismus an Verschiedenen Puncten des Südwestlichen Europa; Hübschmann: Munchen, Germany, 1858. [Google Scholar]

- Mascart, E. Annales du Bureau Central Météorologique de France, Année 1887; Ministére de l’Instruction Publique: Paris, France, 1889. [Google Scholar]

- Dirección General del Instituto Geográfico y Catastral de España. Mapa Magnético de España para la época 1924.0; Instituto Geográfico y Catastral: Madrid, Spain, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Tordesillas, J.M.; Pavón-Carrasco, F.J.; Anquela, A.B.; Camacho, E.; López-Muga, M.; Núñez, A. Geomagnetic declination information extracted from the topographic works of municipal boundaries carried out by IGN in 1871. In Proceedings of the Livro de Resumos Estendidos da 11ª Assembleia Luso-Espanhola de Geodesia e Geofisica, Évora, Portugal, 24–28 June 2024; ISBN 978-972-778-462-2. [Google Scholar]

- Puente-Borque, M.; Pavón-Carrasco, F.J.; Nuñez, A.; Tordesillas, J.M.; Campuzano, S.A. Regional geomagnetic core field and secular variation modelo ver the Iberian Peninsula from 2014 to 2020 based on the R-SCHA technique. Earth Planets Space 2023, 75, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).