A Computational Framework for Reproducible Generation of Synthetic Grain-Size Distributions for Granular and Geoscientific Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Mathematical Models for Particle Size Distribution in Granular Systems

3. Mathematical Foundations of Particle Size Distribution Generation

4. Procedures for Generating Virtual Particle Size Distributions

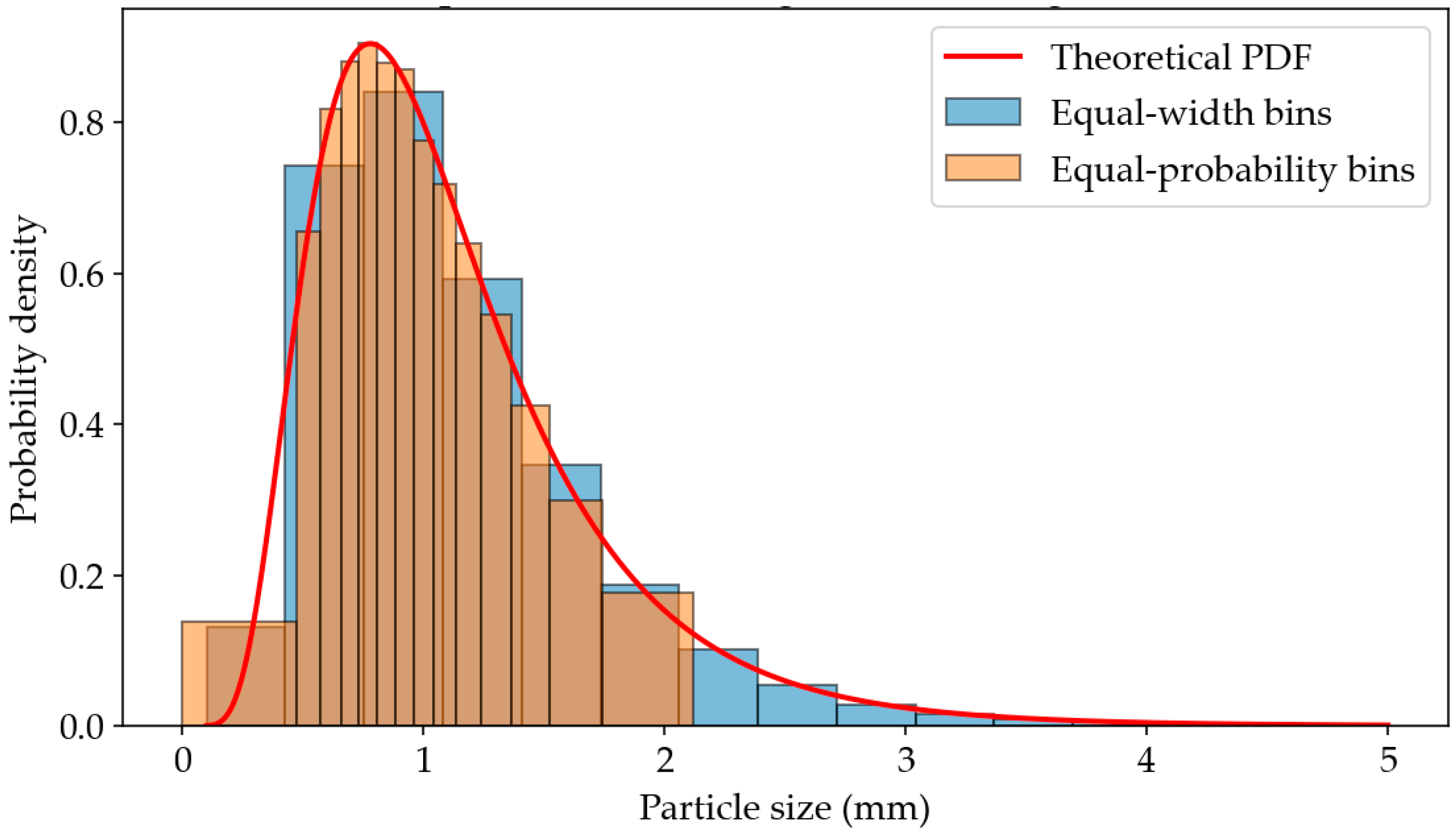

- The equal-width method, which ensures uniform bin spacing across the size range;

- The equal-probability method, which partitions the distribution into bins of equal probability mass based on the target CDF.

4.1. Equal-Width Bin Method

4.2. Equal-Probability Bin Method

4.3. Comparison of Methods

5. Implementation and Case Studies of Synthetic Particle Size Distributions Generation

5.1. Computational Environment

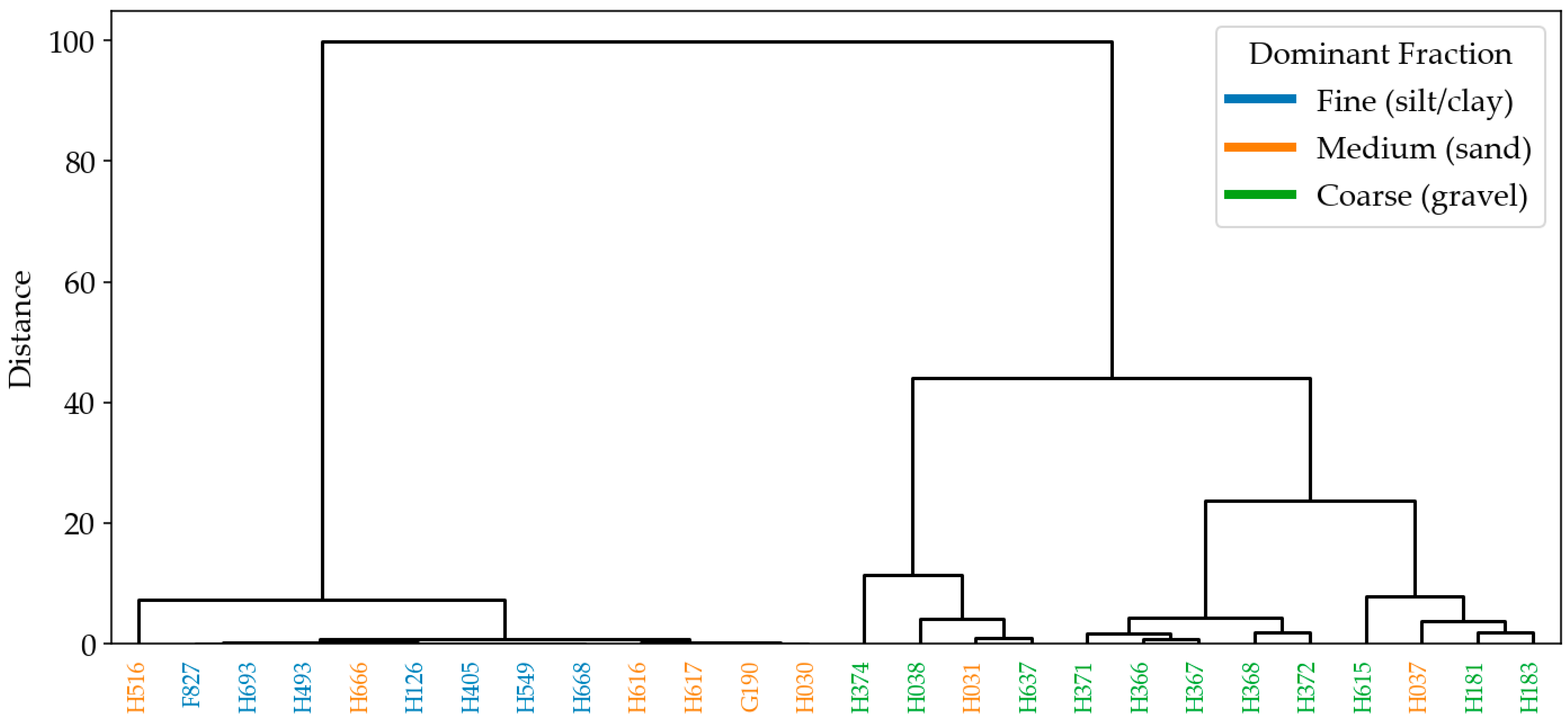

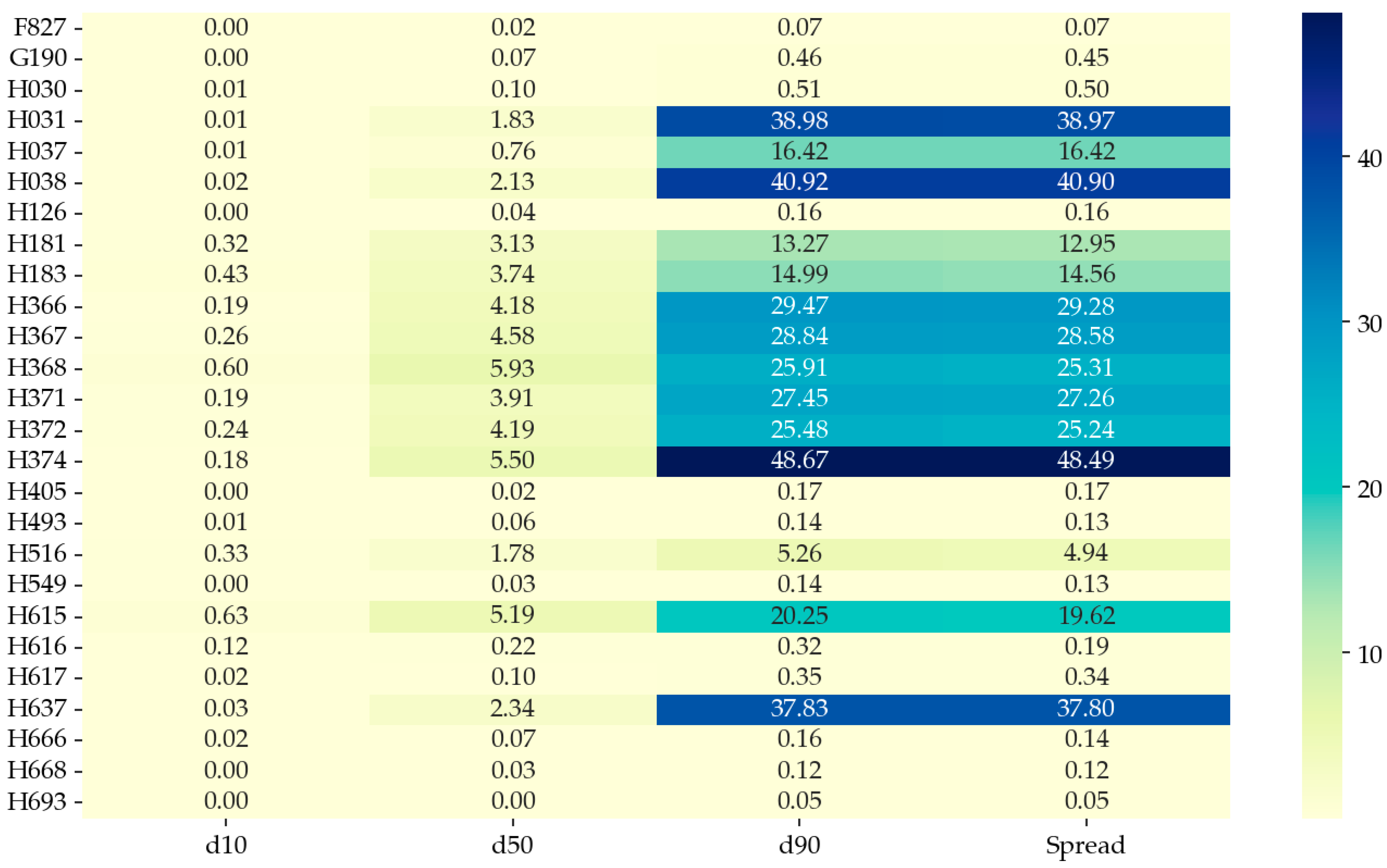

5.2. Generation of Virtual Particle Size Distributions for Soil Analysis Using the Weibull Distribution

5.3. Generation of Virtual Particle Size Distributions for Granular Materials Using the Gamma Distribution

- Controlled reproduction of material-specific PSDs—adjusting α and β allows precise tailoring of particle size distributions without physical measurements;

- Quantitative characterization: PDF/CDF visualization combined with statistical descriptors ensures reproducible and complete description of particle systems;

- Efficiency and scalability—large datasets (100,000 particles) were generated rapidly, enabling simulations, probabilistic analyses, and machine learning applications;

- Universality—the framework is applicable beyond soils, covering industrial, chemical, and organic materials;

- Interpretation of distribution shape—high α yields narrow, uniform distributions, low α produces broad, skewed distributions, demonstrating flexibility in modeling particle heterogeneity.

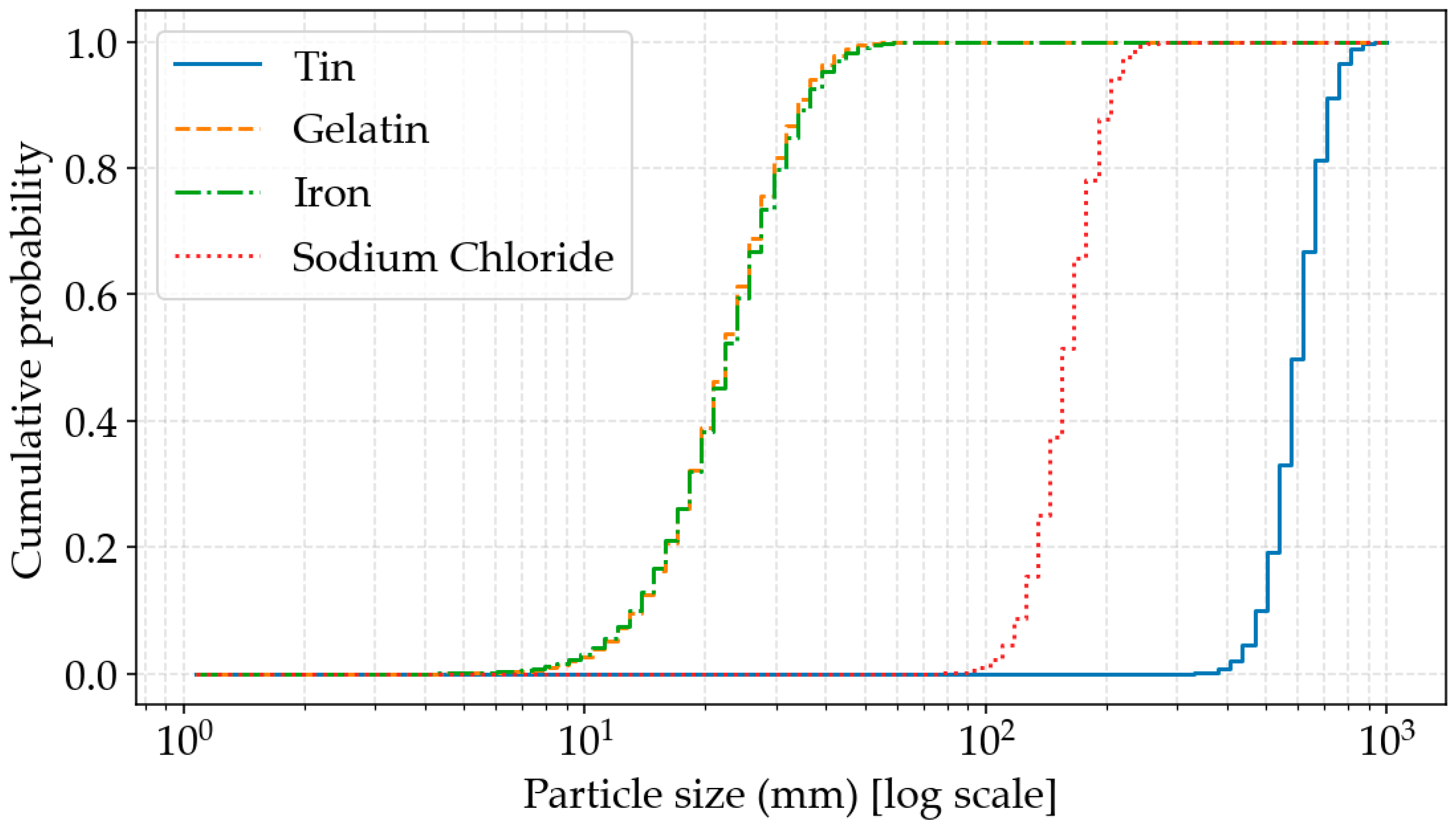

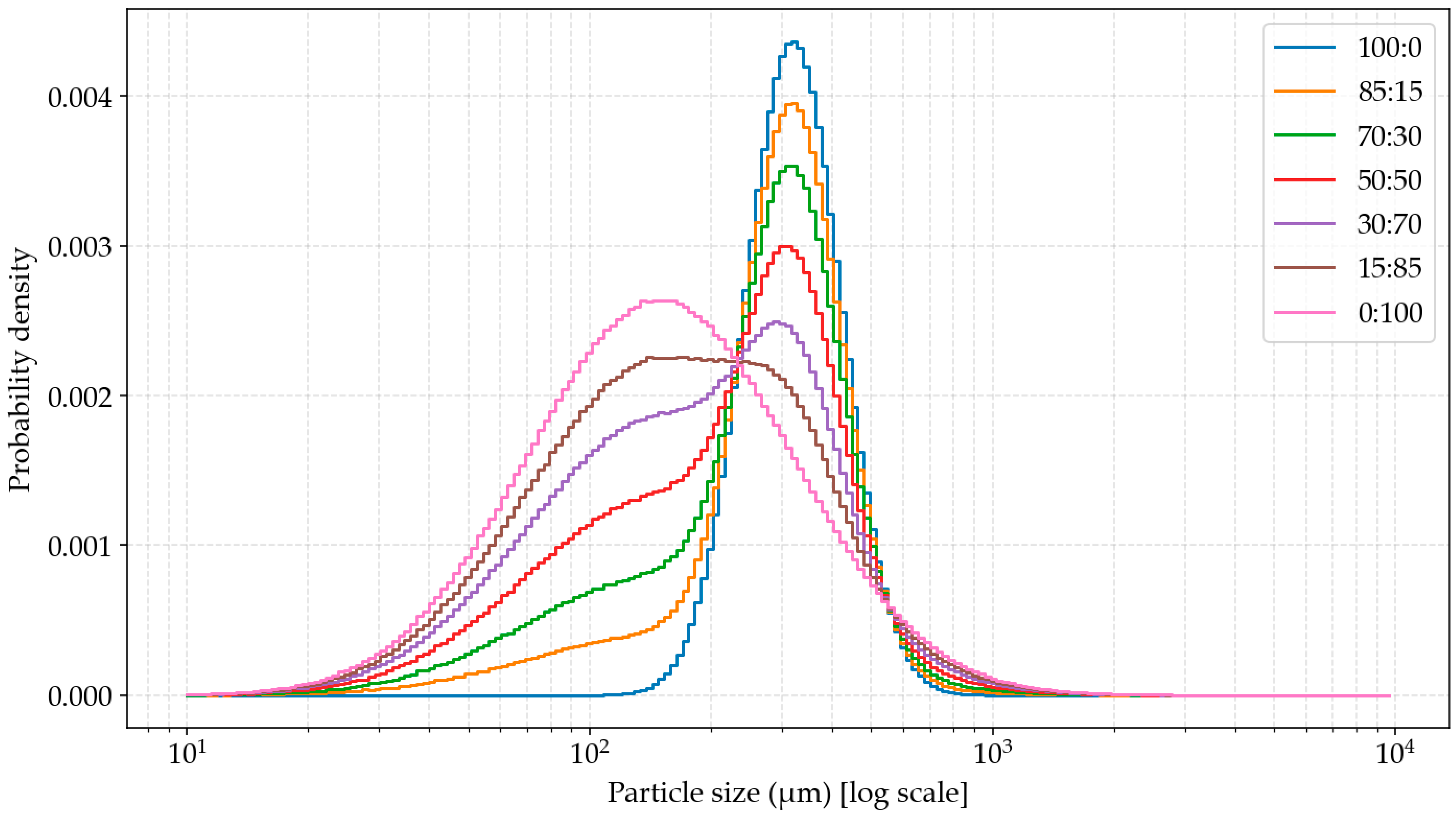

5.4. Generation of Virtual Particle Size Distributions for Food Powders Using the Log-Normal Distribution

5.5. Computational Performance of Histogram Generation Methods

5.6. Discussion of Case Studies, Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDF | Cumulative distribution function |

| Probability density function | |

| PSD | Particle size distribution |

References

- Duran, J. Sands, Powders, and Grains: An Introduction to the Physics of Granular Materials; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guyon, E.; Delenne, J.-Y.; Radjai, F. Built on Sand: The Science of Granular Materials; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, H.M.; Nagel, S.R.; Behringer, R.P. The Physics of Granular Materials. Phys. Today 1996, 49, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liu, C.; Yin, S.; Rehman, A.; Ding, Y.; Wang, L. Particle Size Distribution in a Granular Bed Filter. Particuology 2021, 58, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.L.; Medeiros, M.; Pereira, J.E.; Henriques, G.F.; Tavares, J.C.; Marvila, M.T.; de Azevedo, A.R. Effects of Particle Size Distribution of Standard Sands on the Physical-Mechanical Properties of Mortars. Materials 2023, 16, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.F.; Hawkins, S.M.; Meyer, J.L.; Sharman, A.R. Evaluation of Different Particle Size Distribution and Morphology Characterization Techniques. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2022, 3, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkus, H.G. Particle Size, Size Distributions and Shape. In Particle Size Measurements; Particle Technology Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 17, pp. 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Guo, K.; Xing, Y.; Gui, X. A Comprehensive Review on Evolution Behavior of Particle Size Distribution During Fine Grinding Process for Optimized Separation Purposes. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Barreto, D.; Ding, Z.; Yang, K. Discrete Element Study of Particle Size Distribution Shape Governing Critical State Behavior of Granular Material. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qu, S.; Huang, J. Relationship between Physical Properties and Particle-Size Distribution of Geomaterials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 222, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Montes, F.; Sousa, J.; Pais, A. Comminution Technologies in the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Comprehensive Review with Recent Advances. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2025, 41, 69–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieski, W.; Lipiński, S. The Influence of Particle Size Distribution on Parameters Characterizing the Spatial Structure of Porous Beds. Granul. Matter 2019, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, U. A Review of Particle Shape Effects on Material Properties for Various Engineering Applications: From Macro to Nanoscale. Minerals 2023, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Feng, M.; Mao, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, W.; Ni, X.; Han, G. Particle Size Distribution of Aggregate Effects on Mechanical and Structural Properties of Cemented Rockfill: Experiments and Modeling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 193, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-A.; Sun, J.; Ren, H.; Lu, T.; Ren, Y.; Pang, T. The Effect of Particle Size Distribution and Shape on the Microscopic Behaviour of Loess via the DEM. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujala, U.; Subramanian, V.; Anand, S.; Venkatraman, B. Effect of Morphological Properties on the Particle Size Distribution Measurements and Modelling of Porous and Nonspherical Aerosol Behaviour. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2023, 163, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Cai, X.; Zheng, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, G.; Tan, D.; Luo, X.; Dong, M. Heterogeneous Structures and Morphological Transitions of Composite Materials and Its Applications. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024, 7, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeelnejad, L.; Siavashi, F.; Seyedmohammadi, J.; Shabanpour, M. The Best Mathematical Models Describing Particle Size Distribution of Soils. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2016, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastgou, M.; Bayat, H.; Mansoorizadeh, M. Fitting Soil Particle-Size Distribution (PSD) Models by PSD Curve Fitting Software. Pol. J. Soil Sci. 2019, 52, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Kang, Q.; Xu, X.; Gao, T. Performance Comparison of Different Particle Size Distribution Models in the Prediction of Soil Particle Size Characteristics. Land 2022, 11, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, C.; Arslan, C.A.; Hasanipanah, M.; Bakhshandeh Amnieh, H. Performance Evaluation of Hybrid FFA-ANFIS and GA-ANFIS Models to Predict Particle Size Distribution of a Muck-Pile after Blasting. Eng. Comput. 2021, 37, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, H.; Rastgo, M.; Zadeh, M.M.; Vereecken, H. Particle Size Distribution Models, Their Characteristics and Fitting Capability. J. Hydrol. 2015, 529, 872–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, A.; Blenkinsop, T.; Hobbs, B. Fragment Size Distributions in Brittle Deformed Rocks. J. Struct. Geol. 2022, 154, 104496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Fan, Y.; Yang, R.; Li, S. Application of the Rosin-Rammler Function to Describe Quartz Sandstone Particle Size Distribution Produced by High-Pressure Gas Rapid Unloading at Different Infiltration Pressure. Powder Technol. 2022, 412, 117982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Angel, E.; Eriksen, M.B.; Castro-Alvarez, A.; Garcia, J.H.; Botifoll, M.; Avalos-Ovando, O.; Arbiol, J.; Mugarza, A. Applied Artificial Intelligence in Materials Science and Material Design. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 7, 2400986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokott, S.; Marek, A.; Merz, F.; Karpov, P.; Carbogno, C.; Rossi, M.; Rampp, M.; Blum, V.; Scheffler, M. Towards Efficient and Accurate Input for Data-Driven Materials Science from Large-Scale All-Electron Density Functional Theory (DFT) Simulations. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 32, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kantaros, A.; Ganetsos, T.; Pallis, E.; Papoutsidakis, M. From Mathematical Modeling and Simulation to Digital Twins: Bridging Theory and Digital Realities in Industry and Emerging Technologies. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servin, M.; Vesterlund, F.; Wallin, E. Digital Twins with Distributed Particle Simulation for Mine-to-Mill Material Tracking. Minerals 2021, 11, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrin, K.; Hill, K.M.; Goldman, D.I.; Andrade, J.E. Advances in Modeling Dense Granular Media. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2024, 56, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, C.; Will, F. Introducing Metamodel-Based Global Calibration of Material-Specific Simulation Parameters for Discrete Element Method. Minerals 2021, 11, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieski, W.; Matyka, M.; Gołembiewski, J.; Lipiński, S. The Path Tracking Method as an Alternative for Tortuosity Determination in Granular Beds. Granul. Matter 2018, 20, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aicha, M.B.; Al Asri, Y.; Zaher, M.; Alaoui, A.H.; Burtschell, Y. Prediction of Rheological Behavior of Self-Compacting Concrete by Multi-Variable Regression and Artificial Neural Networks. Powder Technol. 2022, 401, 117345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, N.; Mollehuara, R.; Gonzalez, M.S.; Okkonen, J. Predictive Insight into Tailings Flowability at Their Disposal Using Operating Data-Driven Artificial. Neural Network (ANN) Technique. Minerals 2024, 14, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Mohammed, Z.M.; Ma, J.; Xia, R.; Fan, D.; Tang, J.; Yuan, Q. Machine Learning Driven Fluidity and Rheological Properties Prediction of Fresh Cement-Based Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 5400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soranzo, E. Dataset of Close-Range Soil Images and Corresponding Particle Size Distributions. Data Brief 2025, 60, 111631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soranzo, E.; Guardiani, C.; Wu, W. Convolutional Neural Network Prediction of the Particle Size Distribution of Soil from Close-Range Images. Soils Found. 2025, 65, 101575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es-Saheb, M.H.; Cogun, C.; Al-Matery, S. Statistical Characterization of Particulate Properties of Some Industrial Powders. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2001, 13, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V. Size Characterization of Selected Food Powders by Five Particle Size Distribution Functions Caracterización Del Tamaño de Partícula de Alimentos En Polvo Mediante Cinco Funciones de Distribuciones de Tamaño. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 1997, 3, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, D.F. Particle Size Distributions in Treatment Processes: Theory and Practice. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 36, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, H.; Rastgou, M.; Nemes, A.; Mansourizadeh, M.; Zamani, P. Mathematical Models for Soil Particle-size Distribution and Their Overall and Fraction-wise Fitting to Measurements. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2017, 68, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisselmar, R.; Kellerwessel, H. Approximate Mathematical Description of Particle-Size Distributions—Possibilities and Limitations as to the Assessment of Comminution and Classification Processes. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 1985, 2, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderliesten, M. Mean Particle Diameters. Part VII. The Rosin-Rammler Size Distribution: Physical and Mathematical Properties and Relationships to Moment-Ratio Defined Mean Particle Diameters. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2013, 30, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado-Arango, L.; Menéndez-Aguado, J.M.; Osorio-Correa, A. Particle Size Distribution Models for Metallurgical Coke Grinding Products. Metals 2021, 11, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macıas-Garcıa, A.; Cuerda-Correa, E.M.; Dıaz-Dıez, M.A. Application of the Rosin–Rammler and Gates–Gaudin–Schuhmann Models to the Particle Size Distribution Analysis of Agglomerated Cork. Mater. Charact. 2004, 52, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.E.; Jordan, M.L. Mathematical and Graphical Interpretation of the Log-Normal Law for Particle Size Distribution Analysis. J. Colloid Sci. 1964, 19, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, M.D.; Fredlund, D.G.; Wilson, G.W. An Equation to Represent Grain-Size Distribution. Can. Geotech. J. 2000, 37, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, M.D.; Wilson, G.W.; Fredlund, D.G. Use of Grain-Size Functions in Unsaturated Soil Mechanics. In Proceedings of the Advances in Unsaturated Geotechnics, Denver, CO, USA, 5–8 August 2000; pp. 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bantan, R.A.R.; Jamal, F.; Chesneau, C.; Elgarhy, M. Theory and Applications of the Unit Gamma/Gompertz Distribution. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gohary, A.; Alshamrani, A.; Al-Otaibi, A.N. The Generalized Gompertz Distribution. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosenza, D.N.; Soares, P.; Guerra-Hernández, J.; Pereira, L.; González-Ferreiro, E.; Castedo-Dorado, F.; Tomé, M. Comparing Johnson’s SB and Weibull Functions to Model the Diameter Distribution of Forest Plantations through ALS Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.L. Bivariate Distributions Based on Simple Translation Systems. Biometrika 1949, 36, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niethammer, B.; Pego, R.L. On the Initial-Value Problem in the Lifshitz-Slyozov-Wagner Theory of Ostwald Ripening. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 2000, 31, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, S.; Manetto, G.; Pascuzzi, S.; Pessina, D.; Cerruto, E. Drop Size Measurement Techniques for Agricultural Sprays: A State-of-the-Art Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.-N.; Gusak, A.M.; Sun, Q.; Yao, Y. A Comparison Between Ripening Under a Constant Volume and Ripening Under a Constant Surface Area. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Liang, Y.; Wang, H.; Hu, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Tang, M. Construction and Investigation of a Filtration Efficiency Test System for High-Efficiency Filter Materials Based on Mass Concentration. Processes 2024, 12, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.V.; Ehsani, M.R.; Roy, T.; Sans-Fuentes, M.A.; Ehret, U.; Behrangi, A. Computing Accurate Probabilistic Estimates of One-D Entropy from Equiprobable Random Samples. Entropy 2021, 23, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roederer, M.; Treister, A.; Moore, W.; Herzenberg, L.A. Probability Binning Comparison: A Metric for Quantitating Univariate Distribution Differences. Cytometry 2001, 45, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Distribution Model | Typical Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (Gaussian) | basic modeling, unimodal PSDs | simple, intuitive | allows negative diameters, poor fit for skewed PSDs |

| Rosin–Rammler | mining, comminution, powder technology | simple, widely used, good for crushed materials | limited flexibility for multimodal or skewed PSDs |

| Gaudin–Schuhmann | soil mechanics, mineral processing | easy to apply, intuitive | oversimplified, cannot represent fine fractions accurately |

| Log-normal | sediments, soils, natural materials | flexible, suitable for naturally fragmented systems | poor fit for strongly asymmetric or bimodal PSDs |

| Weibull | fracture mechanics, powders, reliability | versatile, models breakage-dominated processes | parameter estimation sensitive to data quality |

| Gamma | civil engineering, porous media | flexible, effectively models skewness | requires iterative fitting, rarely used |

| Beta | normalized fractions, fine powders | highly flexible, models symmetric and asymmetric shapes | requires normalization, limited intuitive interpretation |

| Fredlund | soil mechanics, gradation curves | captures soil gradation | domain-specific |

| Gompertz | biological fragmentation | suitable for skewed, bounded distributions | weak physical basis |

| Jaky | geotechnics, soil PSDs curves | simple, soil-specific | very limited applicability |

| Johnson (SU, SB, SL, SN) | flexible fitting of skewed PSDs | very versatile, mimics many distributions | complex parameter fitting |

| Lifshitz–Slyozov–Wagner | Ostwald ripening, metallurgy | process-based, time-dependent description | valid only for diffusion-controlled growth |

| Nukiyama–Tanasawa | sprays, atomization, combustion | classical spray droplet law | limited to atomization processes |

| Skaggs | soil physics, hydrology | links PSD with hydraulic properties | soil-specific, limited general use |

| Distribution Model | CDF Availability |

|---|---|

| Normal (Gaussian) | closed form (via error function) |

| Log-normal | closed form (via normal CDF of log(x)) |

| Weibull | closed form |

| Rosin–Rammler | closed form (special case of Weibull model) |

| Gaudin–Schuhmann | closed form (power law) |

| Gamma | closed form (via incomplete gamma function) |

| Beta | closed form (via incomplete beta function) |

| Gompertz | closed form |

| Johnson (SU, SB, SL, SN) | closed forms (transformations of normal CDF) |

| Fredlund | defined empirically |

| Jaky | defined empirically |

| Skaggs | defined empirically |

| Lifshitz–Slyozov–Wagner | no closed form—requires numerical integration |

| Nukiyama–Tanasawa | no closed form—requires numerical integration |

| Distribution Model | CDF | Model Parameter(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal (Gaussian) | —mean particle diameter, —standard deviation (spread) | |

| Log-normal | —mean of —spread of | |

| Weibull | —scale parameter, —shape parameter | |

| Rosin–Rammler | —characteristic particle size, —spread parameter | |

| Gaudin–Schuhmann | —shape parameter | |

| Gamma | —shape parameter, —scale parameter | |

| Beta | , —shape parameters | |

| Gompertz | —scale parameter, —growth/shape | |

| Johnson SU | , —shape parameters, —location, —scale parameter | |

| Johnson SB | , —shape parameters, —location, —scale parameter | |

| Johnson SL | —shape parameter, —location, —scale parameter | |

| Johnson SN | , –shape parameters, —location, —scale parameter |

| Equal-Width Bins | Equal-Probability Bins | |

|---|---|---|

| Bin width | constant across the range | variable (narrow in dense regions, wide in tails) |

| Interpretation | directly comparable heights, standard in PSD analysis | each bin represents the same probability mass |

| Advantages | intuitive, easy comparison with theoretical PDFs, aligns with sieve analysis | highlights tails, ensures all bins are populated |

| Disadvantages | sparse bins in tails, may hide rare events | bar heights less intuitive, variable widths complicate interpretation |

| Computational cost | low computational overhead, only requires linear binning | higher, requires repeated evaluation of the quantile function |

| Best use | comparing PSDs, matching lab data, computing statistics | visualizing quantiles, emphasizing distribution tails, balanced data for ML workflows |

| Soil Type | Scale Parameter (mm) | Shape Parameter | Distribution Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| high-gravel soils | 5–10 | 0.4–0.8 | broad distributions with dominant coarse fractions |

| uniform sands | 0.2–0.3 | >2.5 | steep curves, narrow spread, well-sorted particle sizes |

| fine silty–clayey soils | <0.05 | 0.5–1.0 | steep fine-dominated curves with extended tails in small sizes |

| Material | Mean (mm) | Std Dev (mm) | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tin | 580.6 | 91.2 | 0.31 |

| Gelatin | 22.6 | 8.1 | 0.90 |

| Iron | 22.9 | 8.6 | 0.95 |

| Sodium Chloride | 155.4 | 29.5 | 0.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lipiński, S. A Computational Framework for Reproducible Generation of Synthetic Grain-Size Distributions for Granular and Geoscientific Applications. Geosciences 2025, 15, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120464

Lipiński S. A Computational Framework for Reproducible Generation of Synthetic Grain-Size Distributions for Granular and Geoscientific Applications. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):464. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120464

Chicago/Turabian StyleLipiński, Seweryn. 2025. "A Computational Framework for Reproducible Generation of Synthetic Grain-Size Distributions for Granular and Geoscientific Applications" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120464

APA StyleLipiński, S. (2025). A Computational Framework for Reproducible Generation of Synthetic Grain-Size Distributions for Granular and Geoscientific Applications. Geosciences, 15(12), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120464