Pegmatite and Fault Spatial Distribution Patterns in Kalba-Narym Zone, East Kazakhstan: Integrated Field Observation, GIS, and Remote Sensing Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

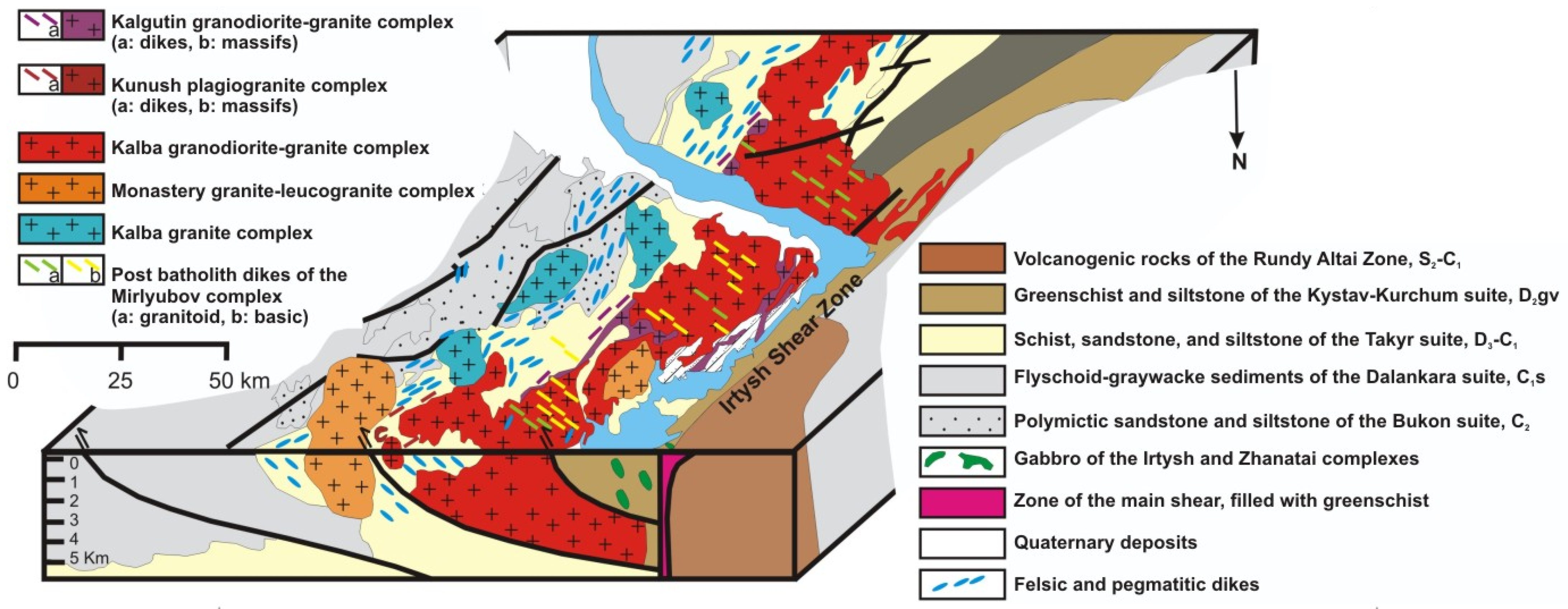

2. Regional Geological Overview

- (1)

- The Rudny-Altai Zone is associated with copper-polymetallic mineralization (Fe, Mn, Cu, Pb, Zn, Au, Ag, etc.). The Rudny-Altai Zone formed along the Siberian active margin as a result of the subduction of the Ob-Zaisan oceanic plate [90];

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

3. Materials and Methods

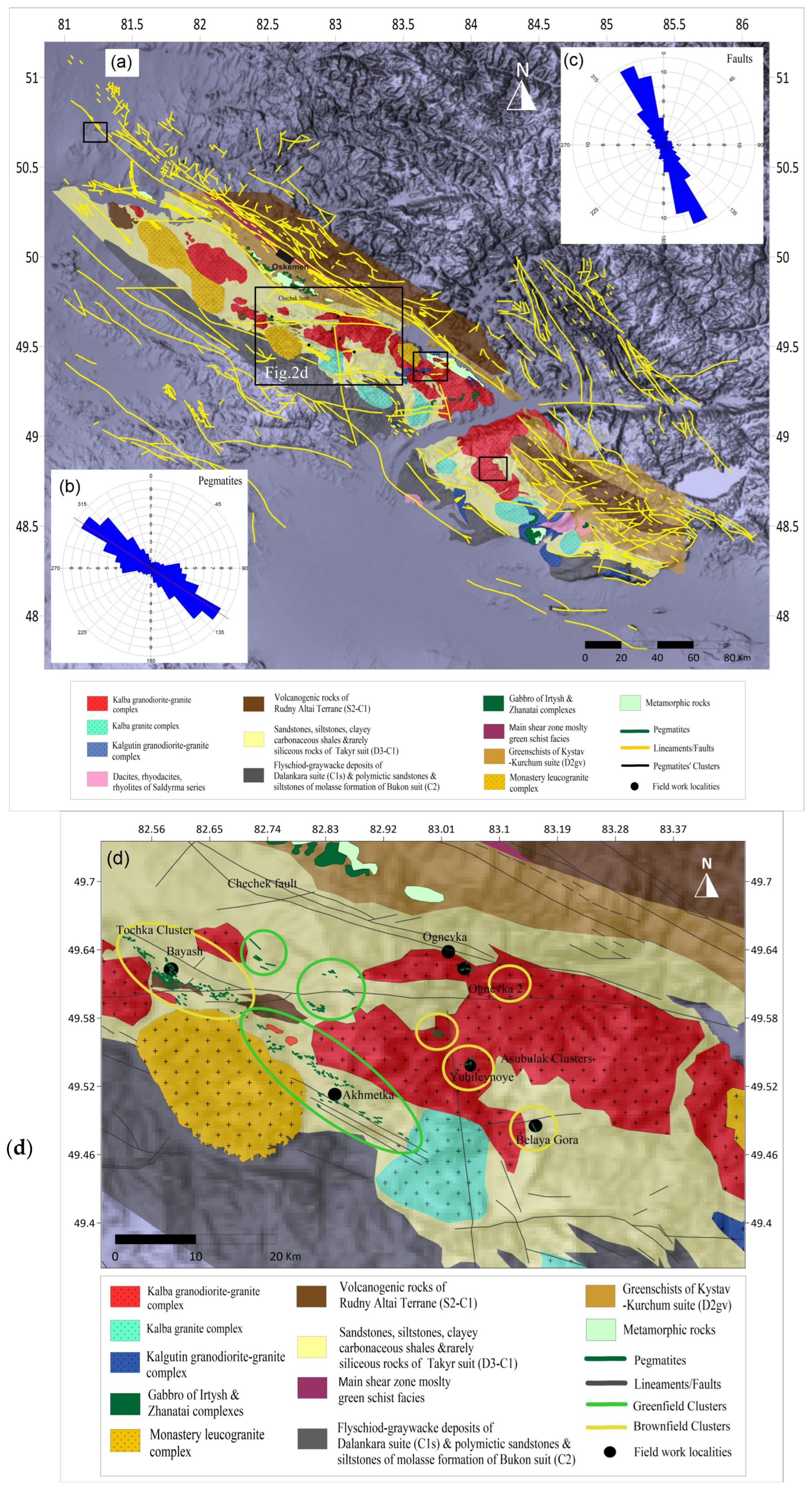

3.1. Study Area and Geological Mapping

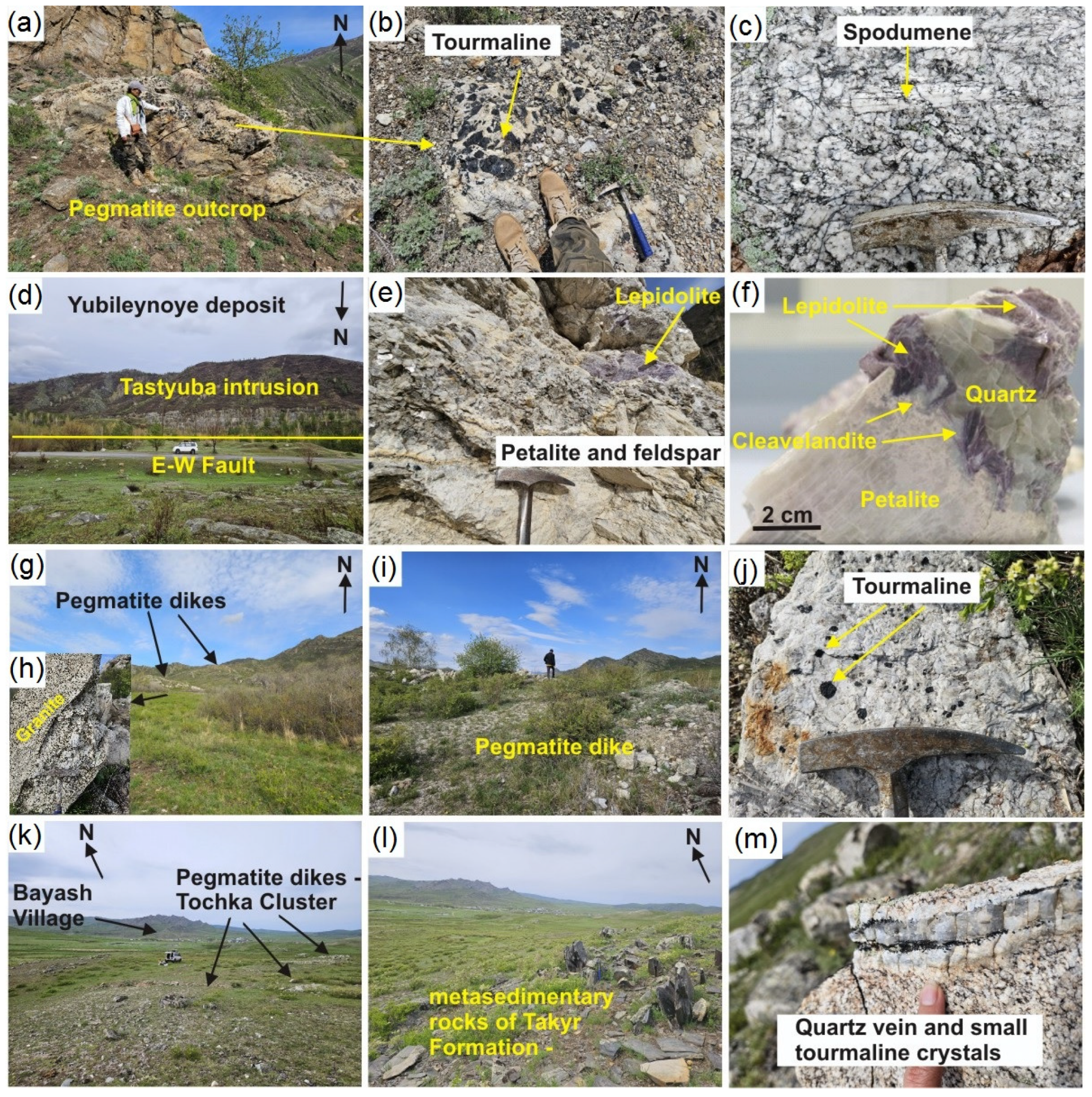

3.2. Pegmatite Localities and Field Observations

3.3. Remote Sensing Lineament Extraction and GIS-Based Data Integration

3.4. DEM Image and Lineaments in Both Manual and Automatic, and Field Observation

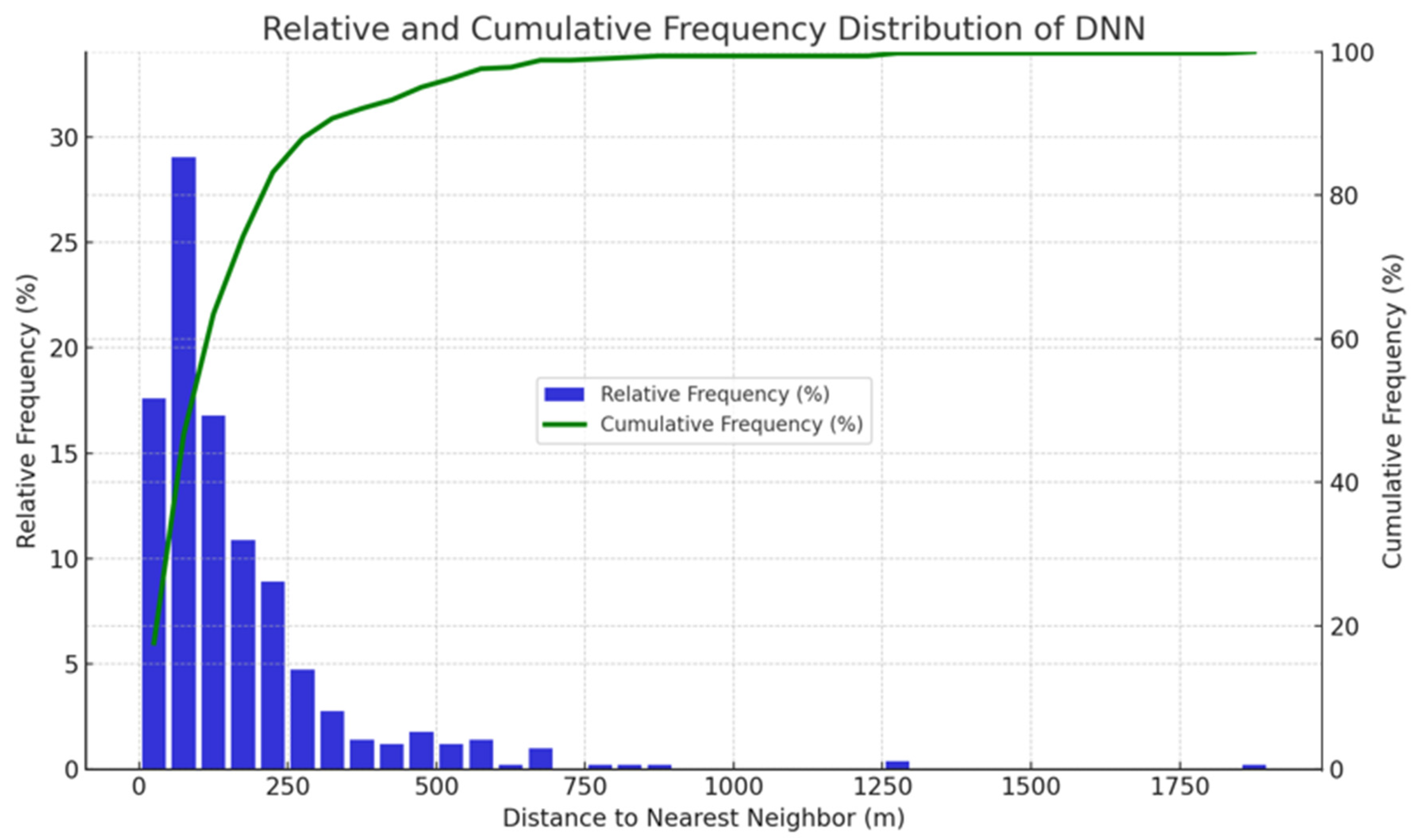

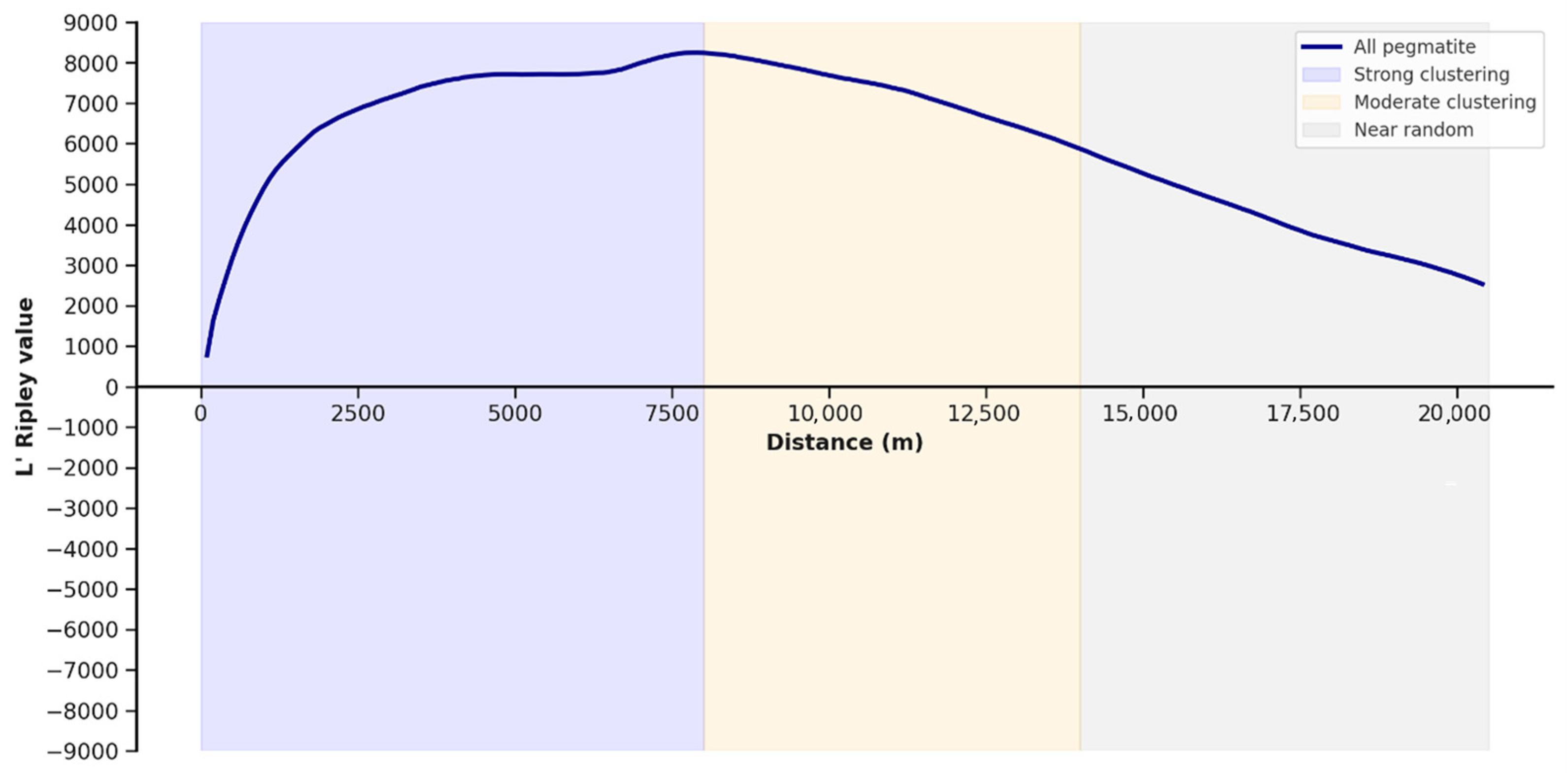

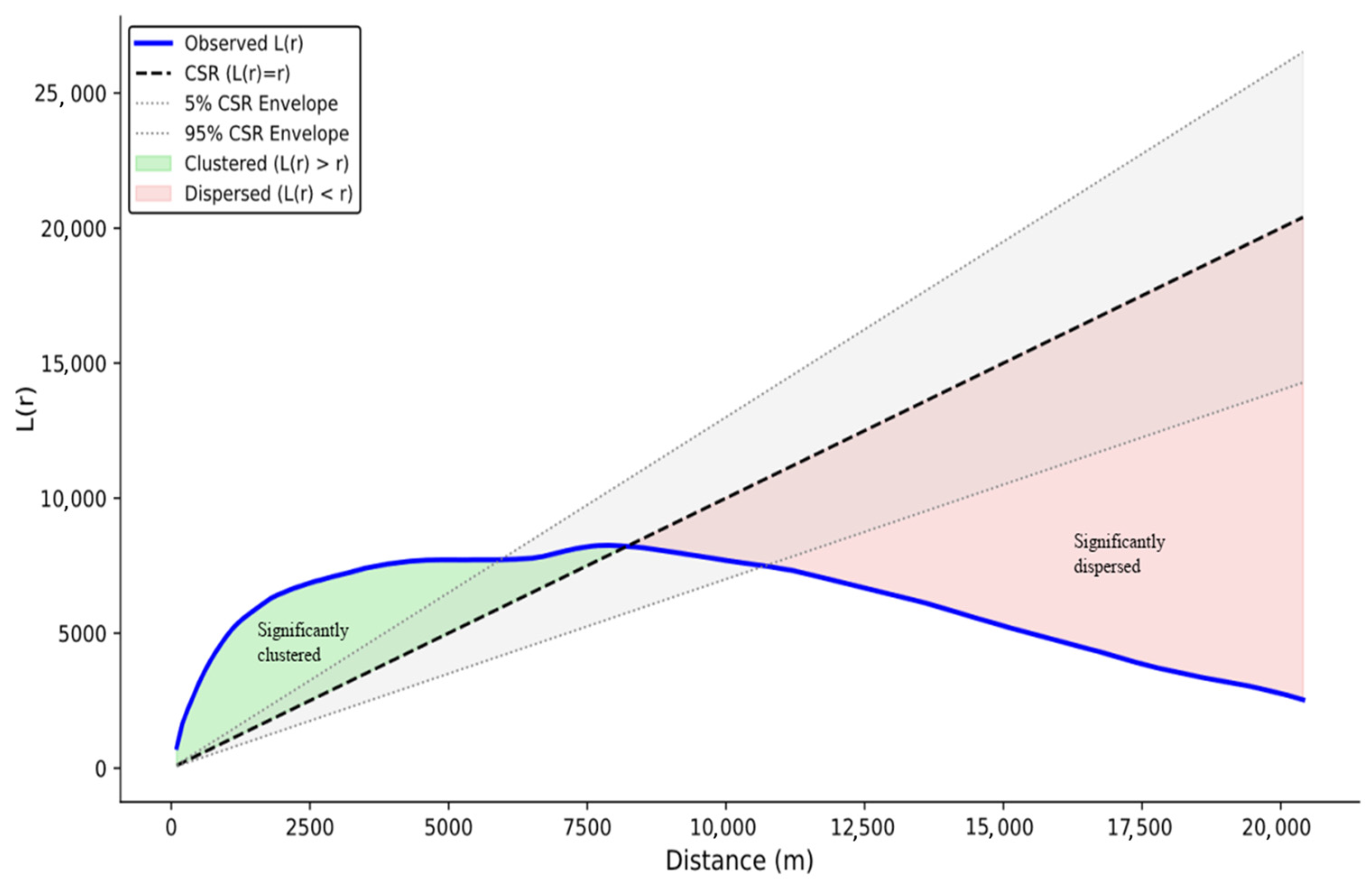

3.5. Spatial Distribution Analysis of Pegmatites

4. Results

4.1. Fault Systems

4.2. Pegmatite Orientation and Special Analysis

4.3. Fieldwork Observation in the Kalba-Narym Zone

5. Discussion

5.1. Structural Features of the Kalba-Narym Zone in the Altai Accretion-Collision System, East Kazakhstan

5.2. Structurally Controlled Granitic Pegmatite and Pegmatite Dike in the Kalba-Narym Zone

5.3. Regional-Scale Pegmatite Remote and GIS-Based Exploration Approach

6. Conclusions

- The dominant structural orientation of the Kalba-Narym Zone is NW-SE, which follows the trend of the major faults in the region. Also, several major E-W trend faults, such as the Asubulak fault, are exposed and show spatial relationships with pegmatite occurrences.

- Most of the detected pegmatite dikes are distributed in a cluster pattern.

- Pegmatites are emplaced at the top of the Kalba batholith or within the metasedimentary lithology of the Takyr suite with proximal distance from the Kalba batholiths.

- The Kalba-Narym pegmatite lineaments share the same orientation as the major fault zones, implying a likely common tectonic origin. The pegmatite dikes observed may have ensued as a response to regional deformation propagating through the study area in an approximate NW-SE direction.

- Upon juxtaposing the structural map of the Kalba-Narym Zone and Pegmatite lineaments, the prospective target area is postulated. In particular, the central sector of the Kalba-Narym Zone demonstrates the highest density of pegmatite dikes occurrence.

- Pegmatite swarms have been observed in localities that have several fault zones intersecting.

- Based on the completion of structural features in this zone, on a large regional scale, using a Geographic Information System (GIS) model for structural and pegmatite exploration can make use of such manifestations and measurements with other investigation techniques to identify the location of prospective resources.

- Uncertainties or biases in spatial data analysis depending on the scale of investigation need to be considered to be able to have a reasonable local and global comparison.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodenough, K.M.; Shaw, R.A.; Smith, M.; Estrade, G.; Marqu, E.; Bernard, C.; Nex, P. Economic mineralization in pegmatites: Comparing and contrasting NYF and LCT examples. Can. Mineral. 2019, 57, 753–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, B.M. Tools and Workflows for Grassroots Li–Cs–Ta (LCT) Pegmatite Exploration. Minerals 2019, 9, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, D. Pegmatites; The Canadian Mineralogist, Special Publication: Greater Sudbury, ON, Canada, 2008; Volume 10, pp. 1–347. [Google Scholar]

- Beskin, S.M.; Marin, Y.B. Granite Systems with Rare-Metal Pegmatites. Geol. Ore Depos. 2020, 62, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černý, P.; Ercit, T.S. The classification of granitic pegmatites revisited. Can. Mineral. 2005, 43, 2005–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, W.B.S.; Webber, K.L. Pegmatite genesis: State of the art. Eur. J. Miner. 2008, 20, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, H.G. Geology and chemistry of Variscan-type pegmatite systems (SE Germany)—With special reference to structural and chemical pattern recognition of felsic mobile components in the crust. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 92, 205–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Romer, R.L.; Augland, L.E.; Zhou, H.; Rosing-Schow, N.; Spratt, J.; Husdal, T. Two-stage regional rare-element pegmatite formation at Tysfjord, Norway: Implications for the timing of late Svecofennian and late Caledonian high-temperature events. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2022, 111, 987–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Simmons, W.; Beurlen, H.; Thomas, R.; Ihlen, P.M.; Wise, M.; Roda-Robles, E.; Neiva, A.M.R.; Zagorsky, V. A proposed new mineralogical classification system for granitic pegmatites—Part I: History and the need for a new classification. Can. Mineral. 2022, 60, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Brönner, M.; Menuge, J.; Williamson, B.; Haase, C.; Tassis, G.; Pohl, C.; Brauch, K.; Saalmann, K.; Teodoro, A.; et al. The GREENPEG Project Toolset to Explore for Buried Pegmatites Hosting Lithium, High-Purity Quartz, and Other Critical Raw Materials. Econ. Geol. 2025, 120, 745–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, J.J.; Redden, J.A. Relations of zoned pegmatites to other pegmatites, granite, and metamorphic rocks in the southern Black Hills, South Dakota. Am. Min. 1990, 75, 631–655. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, T. Multidisciplinary Study of Pegmatites and Associated Li and Sn–Nb–Ta Mineralization from the Barroso–Alvão Region. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Porto, Porto, Portugalia, 2009; pp. 1–196, Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, R. Rare-Elements Aplopegmatites from Al Mandra (V.N. de Foz-Côa) and Barca d’Alva (Figueira Castelo Rodrigo) Regions. Aplopegmatitic Ield of Fre Geneda–ALMENDRA. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Porto, Porto, Portugalia, 2010; pp. 1–274, Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Keyser, W.; Müller, A.; Augland, L.E.; Steiner, R. Rare-metal halos of lithium pegmatite at the Wolfsberg deposit, Austria, and their implications for exploration. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 171, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Romer, R.L.; Pedersen, R.B. The Sveconorwegian Pegmatite Province—Thousands of Pegmatites Without Parental Granites. Can. Mineral. 2017, 55, 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.A.; Goodenough, K.M.; Deady, E.; Nex, P.; Ruzvidzo, B.; Rushton, J.C.; Mounteney, I. The Magmatic–Hydrothermal Transition in Lithium Pegmatites: Petrographic and Geochemical Characteristics of Pegmatites from the Kamativi Area, Zimbabwe. Can. Mineral. 2022, 60, 957–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps-Barber, Z.; Trench, A.; Groves, D.I. Recent pegmatite-hosted spodumene discoveries in Western Australia: Insights for lithium exploration in Australia and globally. Appl. Earth Sci. 2022, 131, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selway, J.B.; Breaks, F.W.; Tindle, A.G. A Review of Rare-Element (Li-Cs-Ta) Pegmatite Exploration Techniques for the Superior Province, Canada, and Large Worldwide Tantalum Deposits. Explor. Min. Geol. 2005, 14, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, A.; Bradley, D.C. The global age distribution of granitic pegmatites. Can. Mineral. 2014, 52, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachev, A.V.; Rundqvist, D.V.; Vishnevskaya, N.A. Metallogeny of lithium through geological time. Rus. J. Earth Sci. 2018, 18, ES6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černý, P. Rare-element granitic pegmatites. Part I: Anatomy and internal evolution of pegmatite deposits. Geosci. Can. 1991, 18, 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer, C.K.; Papike, J.J.; Jolliff, B.L. Petrogenetic links among granites and pegmatites in the Harney Peak rare-element granite-pegmatite system, Black Hills, South Dakota. Can. Mineral. 1992, 30, 785–809. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, B.E.; Warren, C.J.; Jenner, F.E.; Harris, N.B.W.; Argles, T.W. Critical metal enrichment in crustal melts: The role of metamorphic mica. Geology 2022, 50, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Song, D.; Windley, B.F.; Li, J.; Han, C.; Wan, B.; Zhang, J.; Ao, S.; Zhang, Z. Accretionary processes and metallogenesis of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Advances and perspectives. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 63, 329–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Jahn, B.M.; Wilde, S.; Sun, D.Y. Phanerozoic crustal growth: U–Pb and Sr–Nd isotopic evidence from the granites in northeastern China. Tectonophysics 2000, 328, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, B.M.; Wu, F.; Chen, B. Granitoids of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt and continental growth in the Phanerozoic. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 2000, 91, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, V.I.; Yarmolyuk, V.V.; Kovach, V.P.; Kotov, A.B.; Kozakov, I.K.; Salnikova, E.B.; Larin, A.M. Isotope provinces, mechanisms of generation and sources of the continental crust in the Central Asian mobile belt: Geological and isotopic evidence. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2004, 23, 605–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yuan, C.; Xiao, W.; Long, X.; Xia, X.; Zhao, G.; Lin, S.; Wu, F.; Kröner, A. Zircon U–Pb and Hf isotopic study of gneissic rocks from the Chinese Altai: Progressive accretionary history in the early to middle Palaeozoic. Chem. Geol. 2008, 247, 352–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jahn, B.M.; Kovach, V.P.; Tong, Y.; Hong, D.W.; Han, B.F. Nd–Sr isotopic mapping of the Chinese Altai and implications for continental growth in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Lithos 2009, 110, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biske, Y.S. Geology and evolution of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt in Kazakhstan and the western Tianshan. The Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Beiträge Zur Reg. Geol. Der Erde 2015, 32, 6–49. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, G.; Han, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Eizenhöfer, P.R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Tsui, R.W. Geochronology and geochemistry of Paleozoic to Mesozoic granitoids in Western Inner Mongolia, China: Implications for the tectonic evolution of the southern Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Geol. 2018, 126, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, X. Petrogenesis of the Middle Triassic Erenhot granitoid batholith in central Inner Mongolia (northern China) with tectonic implication for the Triassic Mo mineralization in the eastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2018, 165, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windley, B.F.; Kröner, A.; Guo, J.; Qu, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C. Neoproterozoic to Paleozoic geology of the Altai orogen, NW China: New Zircon age data and tectonic evolution. J. Geol. 2002, 110, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuibida, M.L.; Kruk, N.N.; Murzin, O.V.; Shokal’skii, S.P.; Gusev, N.I.; Kirnozova, T.I.; Travin, A.V. Geologic position, age, and petrogenesis of plagiogranites in northern Rudny Altai. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2013, 54, 1305–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.D.; Khromykh, S.V.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Navozov, O.V.; Travin, A.V.; Karavaeva, G.S.; Kruk, N.N.; Murzintsev, N.G. New data on the age and geodynamic interpretation of the Kalba-Narym granitic batholith, eastern Kazakhstan. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2015, 462, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Khromykh, S.; Kruk, N.; Sun, M.; Li, P.; Khubanov, V.; Semenova, D.; Vladimirov, A. Granitoids of the Kalba batholith, Eastern Kazakhstan: U–Pb zircon age, petrogenesis and tectonic implications. Lithos 2021, 388–389, 106056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.D.; Khromykh, S.V.; Zakharova, A.V.; Semenova, D.V.; Kulikova, A.V.; Badretdinov, A.G.; Mikheev, E.I.; Volosov, A.S. Model of the Formation of Monzogabbrodiorite–Syenite–Granitoid Intrusions by the Example of the Akzhailau Massif (Eastern Kazakhstan). Petrology 2024, 32, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suiekpayev, Y.S.; Sapargaliyev, Y.M.; Dolgopolova, A.V.; Pirajno, F.; Seltmann, R.; Khromykh, S.V.; Bekenova, G.K.; Kotler, P.D.; Kravchenko, M.M.; Azelkhanov, A.Z. Mineralogy, geochemistry and U-Pb zircon age of the Karaotkel Ti-Zr placer deposit, Eastern Kazakhstan and its genetic link to the Karaotkel-Preobrazhenka intrusion. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 131, 104015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V.; Izokh, A.E.; Gurova, A.V.; Cherdantseva, M.V.; Savinsky, I.A.; Vishnevsky, A.V. Syncollisional gabbro in the Irtysh shear zone, Eastern Kazakhstan: Compositions, geochronology, and geodynamic implications. Lithos 2019, 346–347, 105144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V.; Semenova, D.V.; Kotler, P.D.; Gurova, A.V.; Mikheev, E.I.; Perfilova, A.A. Orogenic volcanism in Eastern Kazakhstan: Composition, age, and geodynamic position. Geotectonics 2020, 54, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V.; Khokhryakova, O.A.; Kruk, N.N.; Sokolova, E.N.; Kotler, P.D.; Smirnov, S.Z.; Oitseva, T.A.; Semenova, D.V.; Naryzhnova, A.V.; Volosov, A.S.; et al. Petrogenesis of A-type leucocratic granite magmas: An example from Delbegetei massif, Eastern Kazakhstan. Lithos 2024, 482–483, 107696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibai, A.; Chen, X.; Santosh, M.; Wu, Y.; Deng, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Xiao, W.; Chen, Y. Petrology, geochronology, geochemistry, whole-rock Sr-Nd and zircon Lu-Hf isotopes of the Habahe Intrusion in the Chinese Altai: Implications for petrogenesis and tectono-magmatic significance. Lithos 2024, 478–479, 107646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsygankov, A.A.; Burmakina, G.N.; Kotler, P.D. Petrogenesis of Granitoids from Silicic Large Igneous Provinces (Central and Northeast Asia). Petrology 2024, 32, 772–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travin, A.; Buslov, M.; Murzintsev, N.; Korobkin, V.; Kotler, P.; Khromykh, S.V.; Zindobriy, V.D. Thermochronology of the Kalba–Narym Batholith and the Irtysh Shear Zone (Altai Accretion–Collision System): Geodynamic Implications. Minerals 2025, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Yachkov, B.A.; Titov, D.V.; Sapargaliev, E.M. Ore belts of the Greater Altai and their ore resource potential. Geol. Ore Depos. 2009, 51, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Yachkov, B.; Zimanovskaya, N.; Mataibayeva, I.; Dyachkov, B.; Zimanovskaya, N.; Mataibayeva, I. Rare Metal Deposits of East Kazakhstan: Geologic Position and Prognostic Criteria. Open J. Geol. 2013, 3, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Yachkov, B.A.; Amralinova, B.B.; Mataybaeva, I.E.; Dolgopolova, A.V.; Mizerny, A.I.; Miroshnikova, A.P. Laws of Formation and Criteria for Predicting Nickel Content in Weathering Crusts of East Kazakhstan. J. Geol. Soc. India 2017, 89, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Yachkov, B.; Mizernaya, M.; Kuzmina, O.; Zimanovskaya, N.; Oitseva, T. Tectonics and Metallogeny of East Kazakhstan. In Tectonics-Problems of Regional Settings; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2018; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- D′Yachkov, B.A.; Bissatova, A.Y.; Mizernaya, M.A.; Khromykh, S.V.; Oitseva, T.A.; Kuzmina, O.N.; Zimanovskaya, N.A.; Aitbayeva, S.S. Mineralogical Tracers of Gold and Rare-Metal Mineralization in Eastern Kazakhstan. Minerals 2021, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D′Yachkov, B.A.; Mizernaya, M.A.; Khromykh, S.V.; Bissatova, A.Y.; Oitseva, T.A.; Miroshnikova, A.P.; Frolova, O.V.; Kuzmina, O.N.; Zimanovskaya, N.A.; Pyatkova, A.P.; et al. Geological History of the Great Altai: Implications for Mineral Exploration. Minerals 2022, 12, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V.; Oitseva, T.A.; Kotler, P.D.; D’Yachkov, B.A.; Smirnov, S.Z.; Travin, A.V.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Sokolova, E.N.; Kuzmina, O.N.; Mizernaya, M.A.; et al. Rare-Metal Pegmatite Deposits of the Kalba Region, Eastern Kazakhstan: Age, Composition and Petrogenetic Implications. Minerals 2020, 10, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharinov, A.A.; Ponomarenko, V.V.; Pekov, I.V. Rocks & Minerals Color-Change Apatite from Kazakhstan. Rocks Miner. 2010, 83, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V.; Sokolova, E.N.; Smirnov, S.Z.; Travin, A.V.; Annikova, I.Y. Geochemistry and age of rare-metal dike belts in eastern Kazakhstan. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2014, 459, 1587–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, E.N.; Smirnov, S.Z.; Khromykh, S.V. Conditions of crystallization, composition, and sources of rare-metal magmas forming ongonites in the Kalba—Narym zone, Eastern Kazakhstan. Petrology 2016, 24, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oitseva, T.A.; Dyachkov, B.A.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Kuzmina, O.N.; Ageeva, O.V. New data on the substantial composition of Kalba rare metal deposits. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 110, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oitseva, T.; Serikbayev, D.; Mizernaya, M.; Zimanovskaya, N. Zoned rare-metal mineralization in the central Kalba area (East Kazakhstan). In Proceedings of the 22nd International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM, Vienna, Austria, 6–8 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oitseva, T.A.; D’Yachkov, B.A.; Kuzmina, O.N.; Bissatova, A.Y.; Ageyeva, O.V. Li-bearing pegmatites of the Kalba-Narym metallogenic zone (East Kazakhstan): Mineral potential and exploration criteria. Ser. Geol. Tech. Sci. 2022, 1, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oitseva, T.; Serikbayev, D.; Mizernaya, M.; Oitseva, T.; Mizernaya, A.M.; Kuzmina, P.O. Prospects of the Medvedko-Akhmetkinsky ore field for rare metal lithium mineralization (East Kazakhstan). In Proceedings of the 23rd International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 3–9 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oitseva, T. Geological structure and mineralogical composition of the Karayak rare meral ore occurrence (East Kazakhstan). In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference: SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 29 June–8 July 2024; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Amralinova, B.; Agaliyeva, B.; Lozynskyi, V.; Frolova, O.; Rysbekov, K.; Mataibaeva, I.; Mizernaya, M. Rare-metal mineralization in salt lakes and the linkage with composition of granites: Evidence from Burabay rock mass (Eastern Kazakhstan). Water 2023, 15, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimanovskaya, N.A.; Oitseva, T.A.; Khromykh, S.V.; Travin, A.V.; Bissatova, A.Y.; Annikova, I.Y.; Aitbayeva, S.S. Geology, Mineralogy, and Age of Li-Bearing Pegmatites: Case Study of Tochka Deposit (East Kazakhstan). Minerals 2022, 12, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Lei, R.X.; Brzozowski, M.J.; Hao, L.; Zhang, K.; Wu, C.Z. Constraints on the timing of magmatism and rare-metal mineralization in the Fangzheng Rb deposit, Altai, NW China: Implications for the spatiotemporal controls on rare-metal mineralization. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 157, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, R.; Yang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Rare-metal Be–Nb–Ta mineralisation by pegmatite remelting: Insights from Dakalasu deposit in the Chinese Altai orogenic belt. Lithos 2023, 454–455, 107243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, R.; Botcharnikov, R.E.; Sha, H. Formation of rare-element pegmatites in the Chinese Altai: Contribution of two-stage melting. Geology 2025, 53, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhang, X. Petrogenesis of syn-orogenic rare metal pegmatites in the Chinese Altai: Evidences from geology, mineralogy, zircon U-Pb age and Hf isotope. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 95, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Y. Anatexis origin of rare metal/earth pegmatites: Evidences from the Permian pegmatites in the Chinese Altai. Lithos 2021, 380–381, 105865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.P.; Singer, D.A. Mineral Deposit Models (No. 1693); USGPO: Washington, DC, USA, 1986.

- Singer, D.A.; Kouda, R. Application of a feedforward neural network in the search for kuroko deposits in the hokuroku district, Japan. Math. Geol. 1996, 28, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.; Azzalini, A.; Mendes, A.; Cardoso-Fernandes, J.; Lima, A.; Müller, A.; Teodoro, A.C. Optimizing Exploration: Synergistic approaches to minimize false positives in pegmatite prospecting—A comprehensive guide for remote sensing and mineral exploration. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 175, 106347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Liu, Z.; Ning, Y.; Zhao, Z. Extraction and analysis of geological lineaments combining a DEM and remote sensing images from the northern Baoji loess area. Adv. Space Res. 2018, 62, 2480–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveaud, S.; Gumiaux, C.; Gloaguen, E.; Branquet, Y. Spatial statistical analysis applied to rare-element LCT-type pegmatite fields: An original approach to constrain faults- pegmatites-granites relationships. J. Geosci. 2013, 58, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Lima, A.; Gloaguen, E.; Gumiaux, C.; Noronha, F.; Deveaud, S.; Teodoro, A.C. Spatial Geostatistical Analysis Applied to the Barroso-Alvão Rare-Elements Pegmatite Field (Northern Portugal). In GIS—An Overview of Applications; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Groat, L.; Martins, T.; Linnen, R. Structural Controls on the Origin and Emplacement of Lithium-Bearing Pegmatites. Can. J. Mineral. Petrol. 2023, 61, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, G.I.; Vearncombe, J.R. Fault/fracture density and mineralization: A contouring method for targeting in gold exploration. J. Struct. Geol. 2004, 26, 1087–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza, E.J.M. Controls on mineral deposit occurrence inferred from analysis of their spatial pattern and spatial association with geological features. Ore Geol. Rev. 2009, 35, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, R.; Saadi, N.M.; Khalil, A.; Watanabe, K. Integrating remote sensing and magnetic data for structural geology investigation in pegmatite areas in eastern Afghanistan. J. App. Remote Sens. 2015, 9, 096097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Pekkan, E. Fault-Based Geological Lineaments Extraction Using Remote Sensing and GIS—A Review. Geosciences 2021, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forson, E.D.; Menyeh, A.; Wemegah, D.D. Mapping lithological units, structural lineaments and alteration zones in the Southern Kibi-Winneba belt of Ghana using integrated geophysical and remote sensing datasets. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 137, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippova, I.B.; Bush, V.A.; Didenko, A.N. Middle Paleozoic subduction belts: The leading factor in the formation of the Central Asian fold-and-thrust belt. Russ. J. Earth Sci. 2001, 3, 405–426. Available online: https://rjes.ru/en/nauka/article/47173/view (accessed on 1 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zonenshain, L.P. Geology of the USSR: A plate-tectonic synthesis. Geodyn. Ser. 1990, 21, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirov, A.G.; Kruk, N.N.; Rudnev, S.N.; Khromykh, S.V. Geodynamics and granitoid magmatism of collisional orogens. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2003, 44, 1321–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirov, A.G.; Kruk, N.N.; Khromykh, S.V.; Polyansky, O.P.; Chervov, V.V.; Vladimirov, V.G.; Travin, A.V.; Babin, G.A.; Kuibida, M.L.; Vladimirov, V.D. Permian magmatism and lithospheric deformation in the Altai caused by crustal and mantle thermal processes. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2008, 49, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buslov, M.M.; Saphonova, I.Y.; Watanabe, T.; Obut, O.T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Iwata, K.; Semakov, N.N.; Sugai, Y.; Smirnova, L.V.; Kazansky, A.Y. Evolution of the Paleo-Asian Ocean (Altai-Sayan Region, Central Asia) and collision of possible Gondwana-derived terranes with the southern marginal part of the Siberian continent. Geosci. J. 2001, 5, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Natal’In, B.A.; Burtman, V.S. Evolution of the Altaid tectonic collage and Palaeozoic crustal growth in Eurasia. Nature 1993, 364, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buslov, M.M.; Watanabe, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Iwata, K.; Smirnova, L.V.; Safonova, I.Y.; Semakov, N.N.; Kiryanova, A.P. Late Paleozoic faults of the Altai region, Central Asia: Tectonic pattern and model of formation. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2004, 23, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, S.M.; Yin, A.; Manning, C.E.; Chen, Z.L.; Wang, X.F.; Grove, M. Late Paleozoic tectonic history of the Ertix Fault in the Chinese Altai and its implications for the development of the Central Asian Orogenic System. GSA Bull. 2007, 119, 944–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorie, S.; de Grave, J.; Delvaux, D.; Buslov, M.M.; Zhimulev, F.I.; Vanhaecke, F.; Elburg, M.A.; Haute, P.V.D. Tectonic history of the Irtysh shear zone (NE Kazakhstan): New constraints from zircon U/Pb dating, apatite fission track dating and palaeostress analysis. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 45, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Sun, M.; Li, P.; Zheng, J.; Cai, K.; Su, Y. Late paleozoic accretionary and collisional processes along the southern peri-siberian orogenic system: New constraints from amphibolites within the irtysh complex of chinese altai. J. Geol. 2019, 127, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V.; Tsygankov, A.A.; Kotler, P.D.; Navozov, O.V.; Kruk, N.N.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Travin, A.V.; Yudin, D.S.; Burmakina, G.N.; Khubanov, V.B.; et al. Late Paleozoic granitoid magmatism of Eastern Kazakhstan and Western Transbaikalia: Plume model test. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2016, 57, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuibida, M.L.; Murzin, O.V.; Kruk, N.N.; Safonova, I.Y.; Sun, M.; Komiya, T.; Wong, J.; Aoki, S.; Murzina, N.M.; Nikolaeva, I.; et al. Whole-rock geochemistry and U-Pb ages of Devonian bimodal-type rhyolites from the Rudny Altai, Russia: Petrogenesis and tectonic settings. Gondwana Res. 2020, 81, 312–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatnikov, V.V.; Izokh, E.P.; Ermolov, P.V.; Ponomareva, A.P.; Stepanov, A.S. Magmatism and Metallogeny of the Kalba-Narym Zone, Eastern Kazakhstan; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1982; p. 248. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kuibida, M.L.; Safonova, I.Y.; Yermolov, P.V.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Kruk, N.N.; Yamamoto, S. Tonalites and plagiogranites of the Char suture-shear zone in East Kazakhstan: Implications for the Kazakhstan-Siberia collision. Geosci. Front. 2016, 7, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuibida, M.L.; Kruk, N.N.; Volkova, N.I.; Serov, P.A.; Velivetskaya, T.A. Composition, sources, and genesis of granitoids in the Irtysh Complex, Eastern Kazakhstan. Petrology 2012, 20, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safonova, I.; Komiya, T.; Romer, R.L.; Simonov, V.; Seltmann, R.; Rudnev, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Sun, M. Supra-subduction igneous formations of the Char ophiolite belt, East Kazakhstan. Gondwana Res. 2018, 59, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degtyarev, K.E.; Shatagin, K.N.; Kovach, V.P.; Tretyakov, A.A. The formation processes and isotopic structure of continental crust of the Chingiz Range Caledonides (Eastern Kazakhstan). Geotectonics 2015, 49, 485–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windley, B.F.; Alexeiev, D.; Xiao, W.; Kröner, A.; Badarch, G. Tectonic models for accretion of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Geol. Soc. 2007, 164, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Huang, B.; Han, C.; Sun, S.; Li, J. A review of the western part of the Altaids: A key to understanding the architecture of accretionary orogens. Gondwana Res. 2010, 18, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirov, A.G.; Kozlov, M.S.; Shokal’skii, S.P.; Khalilov, V.A.; Rudnev, S.N.; Kruk, N.N.; Vystavnoi, S.A.; Borisov, S.M.; Bereziko, Y.K.; Metsner, A.N.; et al. Major epochs of intrusive magmatism of Kuznetsk Alatau, Altai, and Kalba (from U-Pb isotope dates). Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2001, 42, 1089–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Ripley, B.D. Modelling Spatial Patterns. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1977, 39, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiskowski, M.A.; Hancock, J.F.; Kenworthy, A.K. On the use of Ripley’s K-function and its derivatives to analyze domain size. Biophys. J. 2009, 97, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, V.; Zas, R.; Solla, A. Spatial structure of deciduous forest stands with contrasting human influence in northwest Spain. Eur. J. For. Res. 2009, 128, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goreaud, F.; Pélissier, R. On explicit formulas of edge effect correction for Ripley’s K--function. J. Veg Sci. 1999, 10, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari Mamaghani, M.; Andersson, M.; Krieger, P. Spatial point pattern analysis of neurons using Ripley’s K-function in 3D. Front. Neuroinform. 2010, 4, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pélissier, R.; Goreaud, F. Ads package for R: A fast unbiased implementation of the K-function family for studying spatial point patterns in irregular-shaped sampling windows. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengör, A.C.; Natal’In, B.A. Turkic-type orogeny and its role in the making of the continental crust. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1996, 24, 263–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent-Charvet, S.; Charvet, J.; Monié, P.; Shu, L. Late Paleozoic strike-slip shear zones in eastern central Asia (NW China): New structural and geochronological data. Tectonics 2003, 22, 1009–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, A.; Delvaux, D.; Travin, A.; Buslov, M.; Vladimirov, A.; Smirnova, L.; Theunissen, K. Late Paleozoic–Early Mesozoic Sinistral Movement Along the Irtysh Shear Zone, NE Kazakhstan. In Proceedings of the Tectonic Studies Group Annual General Meeting, Durham, UK, 17–19 December 1997; pp. 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Melnikov, A.; Travin, A.; Plotnikov, A.; Smirnova, L.; Theunissen, K. Kinematics and Ar/Ar Geochronology of the Irtysh Shear Zone in NE Kazakhstan. In Proceedings of the Continental Growth in the Phanerozoic: Evidence from East-Central Asia, First Workshop, IGCP-420, Urumqi, China, 27 July–3 August 1998; Volume 27, p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Mileyev, V.S.; Rotarash, I.A.; Samygin, S.G. The Irtysh crush belt: Doklady Earth Sciences. Dokl. Adademii Nauk. SSSR 1980, 255, 413–416. [Google Scholar]

- Rotarash, A.I.; Samygin, S.G.; Gredyushko, A.Y.; Keyl’man, G.A.; Mileyev, V.S.; Perfil’yev, A.S. The Devonian active continental margin in the southwestern Altay. Geotectonics 1982, 16, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Travin, A.V.; Boven, A.; Plotnikov, A.V.; Vladimirov, V.G.; Tenissen, K.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Melnikov, A.I.; Titov, A.V. 40Ar/39Ar Dating of Plastic Deformations in the Irtysh Shear Zone (Eastern Kazakhstan). Geochem. Int. 2001, 12, 1–5. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Korobkin, V.V.; Buslov, M.M. Tectonics and geodynamics of the western Central Asian Fold Belt (Kazakhstan Paleozoides). Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2011, 52, 1600–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Natal’in, B.A.; Sunal, G.; van der Voo, R. A new look at the Altaids: A superorogenic complex in northern and central Asia as a factory of continental crust. Part I: Geological data compilation (exclusive of palaeomagnetic observations). Austrian J. Earth Sci. 2014, 107, 169–232. [Google Scholar]

- Travin, A.V. Thermochronology of Early Paleozoic collisional and subduction–collisional structures of Central Asia. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2016, 57, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvaux, D.; Cloetingh, S.; Beekman, F.; Sokoutis, D.; Burov, E.; Buslov, M.M.; Abdrakhmatov, K.E. Basin evolution in a folding lithosphere: Altai–Sayan and Tien Shan belts in Central Asia. Tectonophysics 2013, 602, 194–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.F.; Zeng, Y.; Gu, L. Geochemistry of the rare metal-bearing pegmatite No. 3 vein and related granites in the Keketuohai region, Altay Mountains, northwest China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2006, 27, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, X. Petrogenesis of Devonian and Permian Pegmatites in the Chinese Altay: Insights into the Closure of the Irtysh–Zaisan Ocean. Minerals 2023, 13, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.F.; De Vito, C. The patterns of enrichment in felsic pegmatites ultimately depend on tectonic setting. Can. Mineral. 2005, 43, 2027–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, D. Ore-forming processes within granitic pegmatites. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 101, 349–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piilonen, P.C.; McDonald, A.M.; Poirier, G.; Rowe, R.; Larsen, A.O. The mineralogy and crystal chemistry of alkaline pegmatites in the Larvik Plutonic Complex, Oslo rift valley, Norway. Part 1. Magmatic and secondary zircon: Implications for petrogenesis from trace-element geochemistry. Mineral. Mag. 2012, 76, 649–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagorsky, V.Y.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Makagon, V.M.; Kuznetsova, L.G.; Smirnov, S.Z.; D’yachkov, B.A.; Annikova, I.Y.; Shokalsky, S.P.; Uvarov, A.N. Large fields of spodumene pegmatites in the settings of rifting and postcollisional shear–pull-apart dislocations of continental lithosphere. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2014, 55, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T.; Kankuzi, C.F.; Glodny, J.; Frei, D.; Büttner, S.H. The timing and tectonic context of Pan-African gem bearing pegmatites in Malawi: Evidence from Rb–Sr and U–Pb geochronology. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2023, 197, 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirajno, F.; Seltmann, R.; Yang, Y. A review of mineral systems and associated tectonic settings of northern Xinjiang, NW China. Geosci. Front. 2011, 2, 157–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safonova, I. The Russian-Kazakh Altai orogen: An overview and main debatable issues. Geosci. Front. 2014, 5, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buslov, M.M. Tectonics and geodynamics of the Central Asian Foldbelt: The role of Late Paleozoic large-amplitude strike-slip faults. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2011, 52, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, H.; Cavalcante, G.C.G. Shear zones—A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 2017, 171, 434–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, D. Granitic pegmatites: An assessment of current concepts and directions for the future. Lithos 2005, 80, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsbosch, N.; van Daele, J.; Reinders, N.; Dewaele, S.; Jacques, D.; Muchez, P. Structural control on the emplacement of contemporaneous Sn-Ta-Nb mineralized LCT pegmatites and Sn bearing quartz veins: Insights from the Musha and Ntunga deposits of the Karagwe-Ankole Belt, Rwanda. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2017, 134, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndikumana, J.d.D.; Mupenge, P.M.; Nambaje, C.; Raoelison, I.L.; Bolarinwa, A.T.; Adeyemi, G.O. Structural control on the Sn-Ta-Nb mineralisation and geochemistry of the pegmatites of Gitarama and Gatumba areas (Rwanda), Karagwe–Ankole Belt. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chen, X.H.; Dong, S.W.; Chen, Z.L.; Han, S.Q.; Yang, Y.; Ye, B.Y.; Shi, W. Geochemistry of late Palaeozoic granitoids of the Balkhash metallogenic belt, Kazakhstan: Implications for crustal growth and tectonic evolution of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Int. Geol. Rev. 2017, 59, 1053–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomareva, Y.V. Age and geodynamics of the Irtysh shear zone. Natsional’nyi Hirnychyi Universytet Nauk. Visnyk 2018, 6, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Sanità, E.; Lardeaux, J.M.; Marroni, M.; Pandolfi, L. Kinematics of the Helminthoid Flysch–Marguareis Unit tectonic coupling: Consequences for the tectonic evolution of Western Ligurian Alps. Comptes Rendus. Géoscience 2022, 354, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahns, R.H.; Burnham, C.W. Experimental studies of pegmatite genesis; l, A model for the derivation and crystallization of granitic pegmatites. Econ. Geol. 1969, 64, 843–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunder, A.; Le Pourhiet, L.; Räss, L.; Gloaguen, E.; Pichavant, M.; Gumiaux, C. Pegmatites as geological expressions of spontaneous crustal flow localisation. Lithos 2022, 416, 106652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, T.; Moloney, K.A. Handbook of Spatial Point-Pattern Analysis in Ecology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soltani Dehnavi, A.; Shahzad, S.M.; Skrzypacz, P.; Shabani-Sefiddashti, F. Pegmatite and Fault Spatial Distribution Patterns in Kalba-Narym Zone, East Kazakhstan: Integrated Field Observation, GIS, and Remote Sensing Analysis. Geosciences 2025, 15, 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120458

Soltani Dehnavi A, Shahzad SM, Skrzypacz P, Shabani-Sefiddashti F. Pegmatite and Fault Spatial Distribution Patterns in Kalba-Narym Zone, East Kazakhstan: Integrated Field Observation, GIS, and Remote Sensing Analysis. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):458. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120458

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoltani Dehnavi, Azam, Syed Muzyan Shahzad, Piotr Skrzypacz, and Fereshteh Shabani-Sefiddashti. 2025. "Pegmatite and Fault Spatial Distribution Patterns in Kalba-Narym Zone, East Kazakhstan: Integrated Field Observation, GIS, and Remote Sensing Analysis" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120458

APA StyleSoltani Dehnavi, A., Shahzad, S. M., Skrzypacz, P., & Shabani-Sefiddashti, F. (2025). Pegmatite and Fault Spatial Distribution Patterns in Kalba-Narym Zone, East Kazakhstan: Integrated Field Observation, GIS, and Remote Sensing Analysis. Geosciences, 15(12), 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120458