Estimating the Groundwater Recharge Sources to Spring-Fed Lake Ezu, Kumamoto City, Japan from Hydrochemical Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

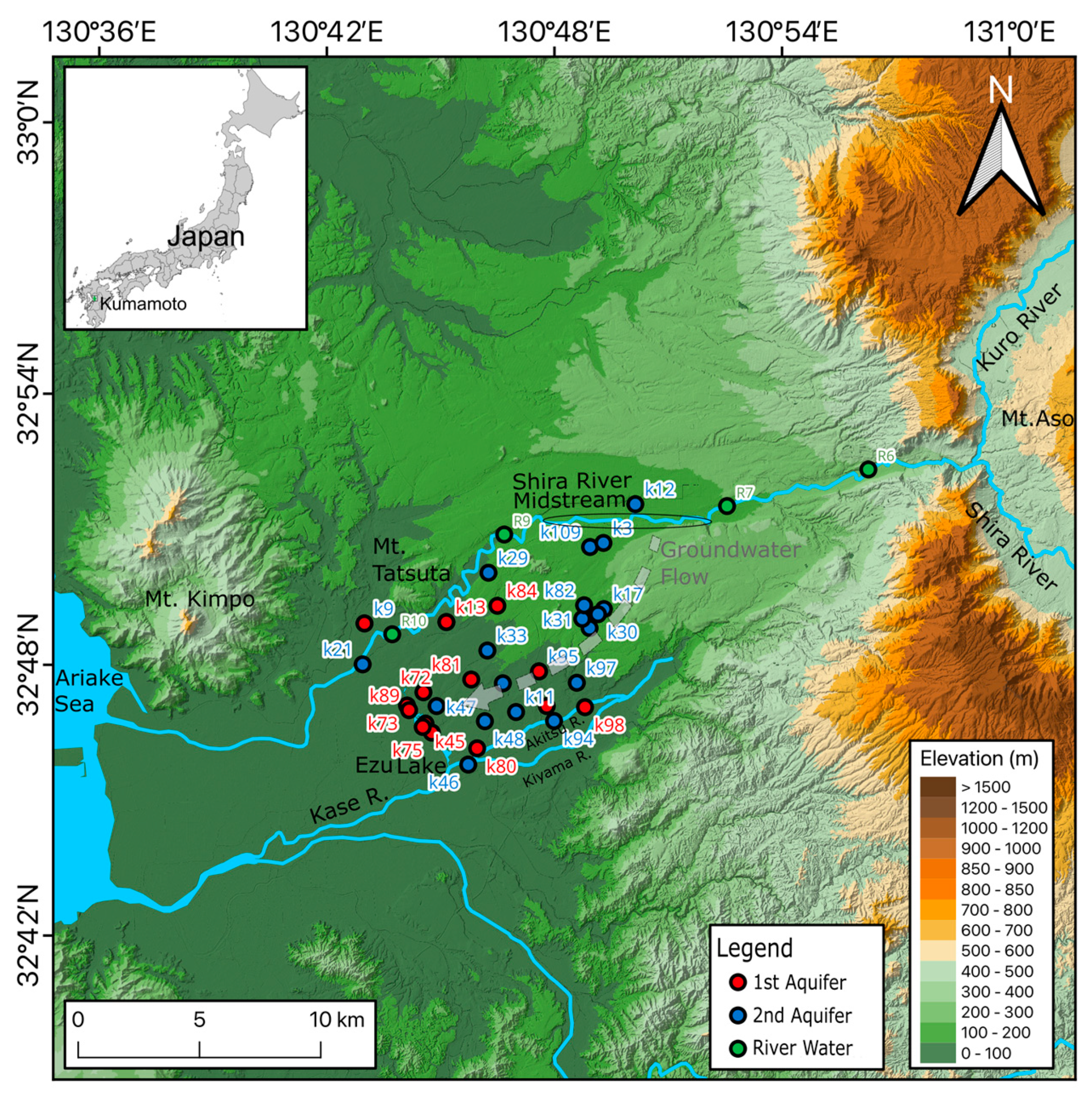

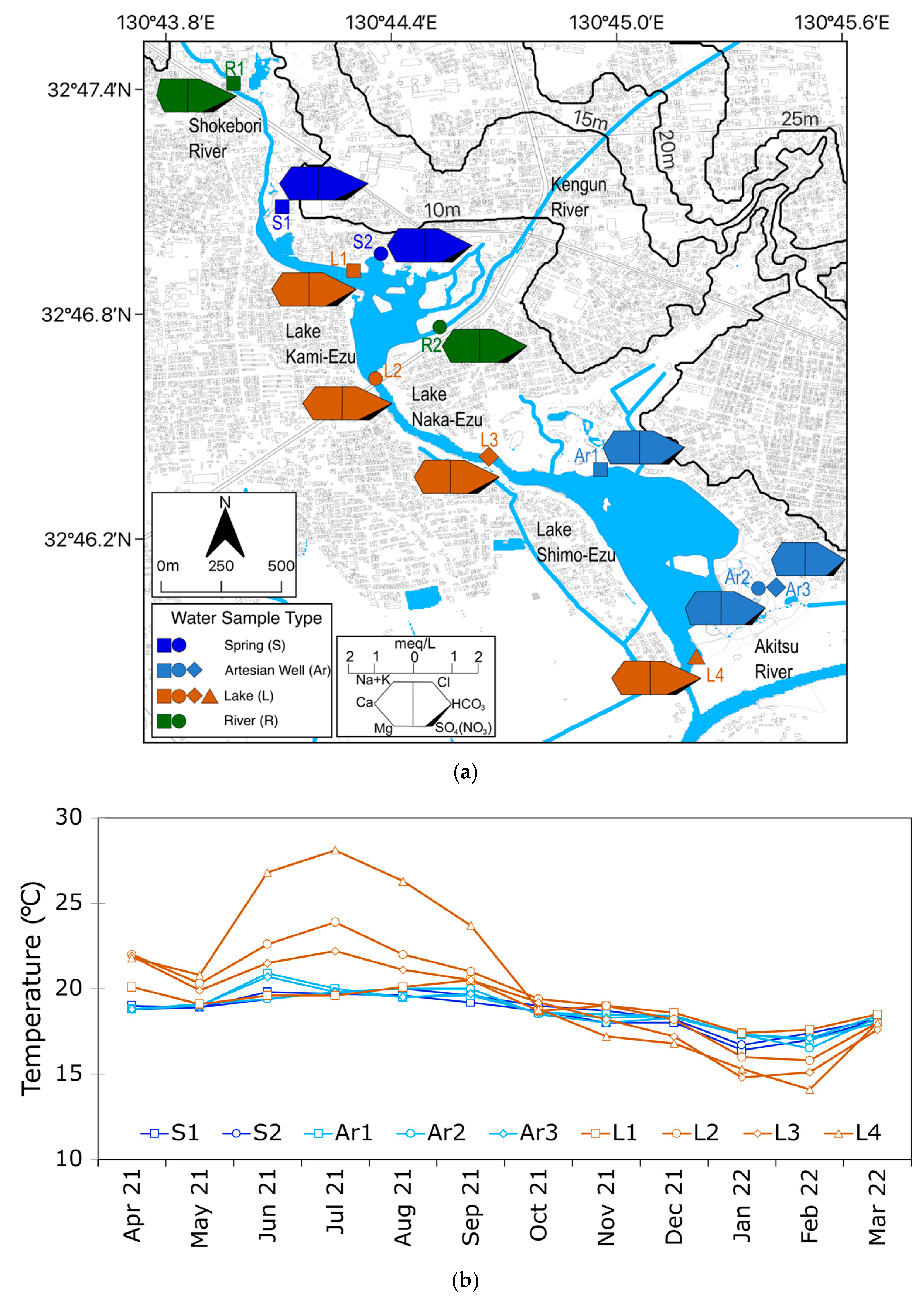

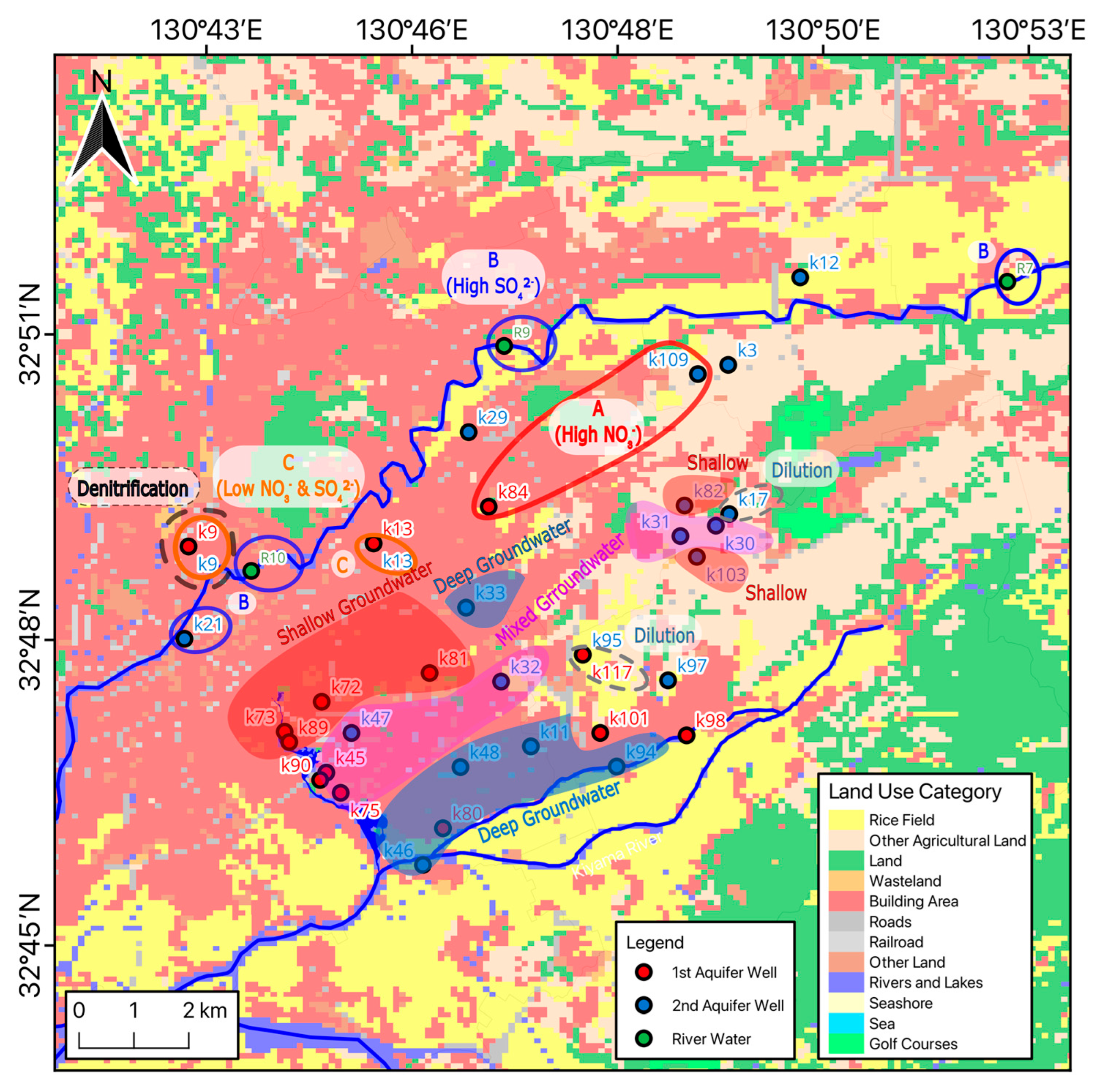

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Methods

3. Results

3.1. In Situ Measurements

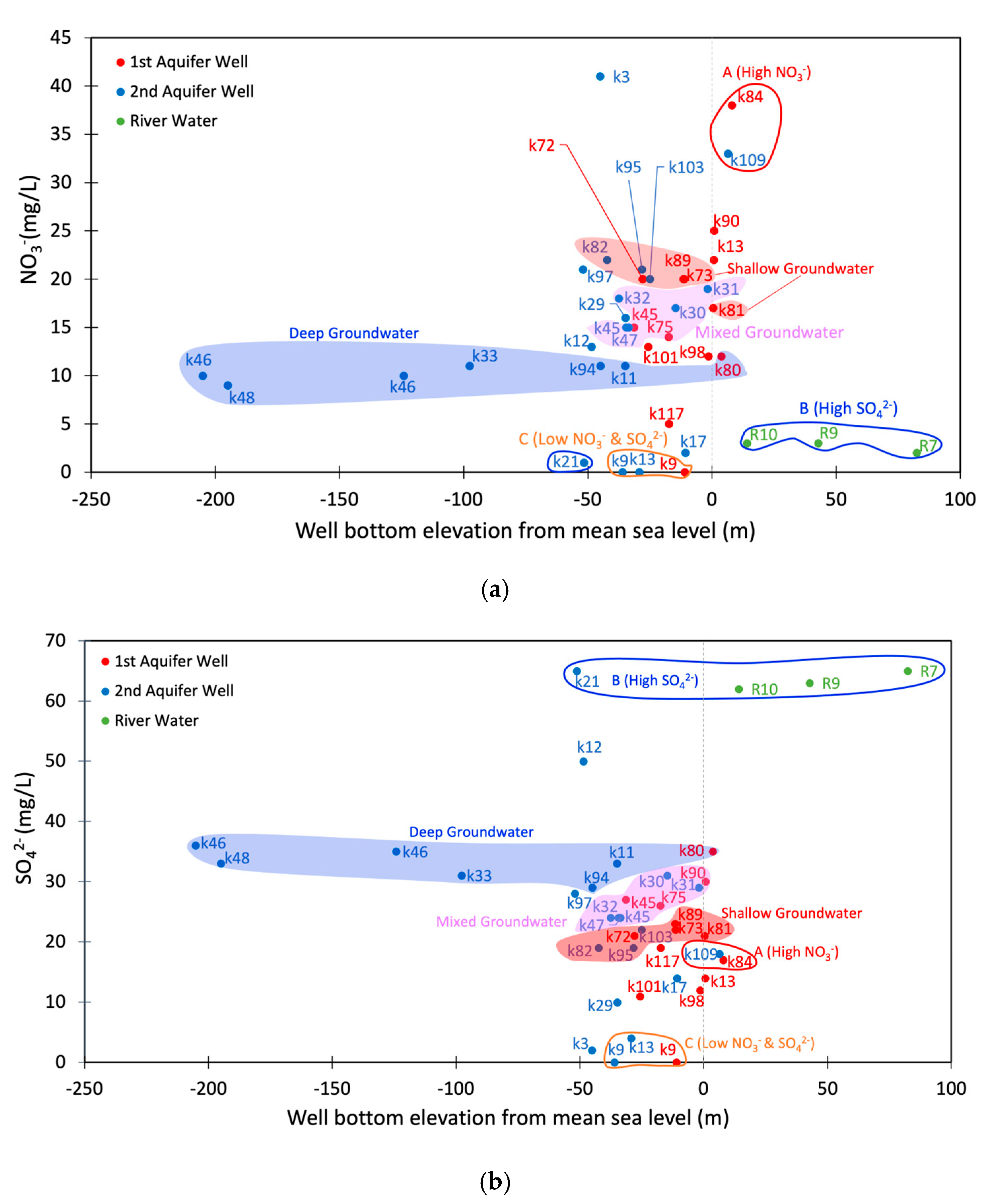

3.2. Chemical Properties

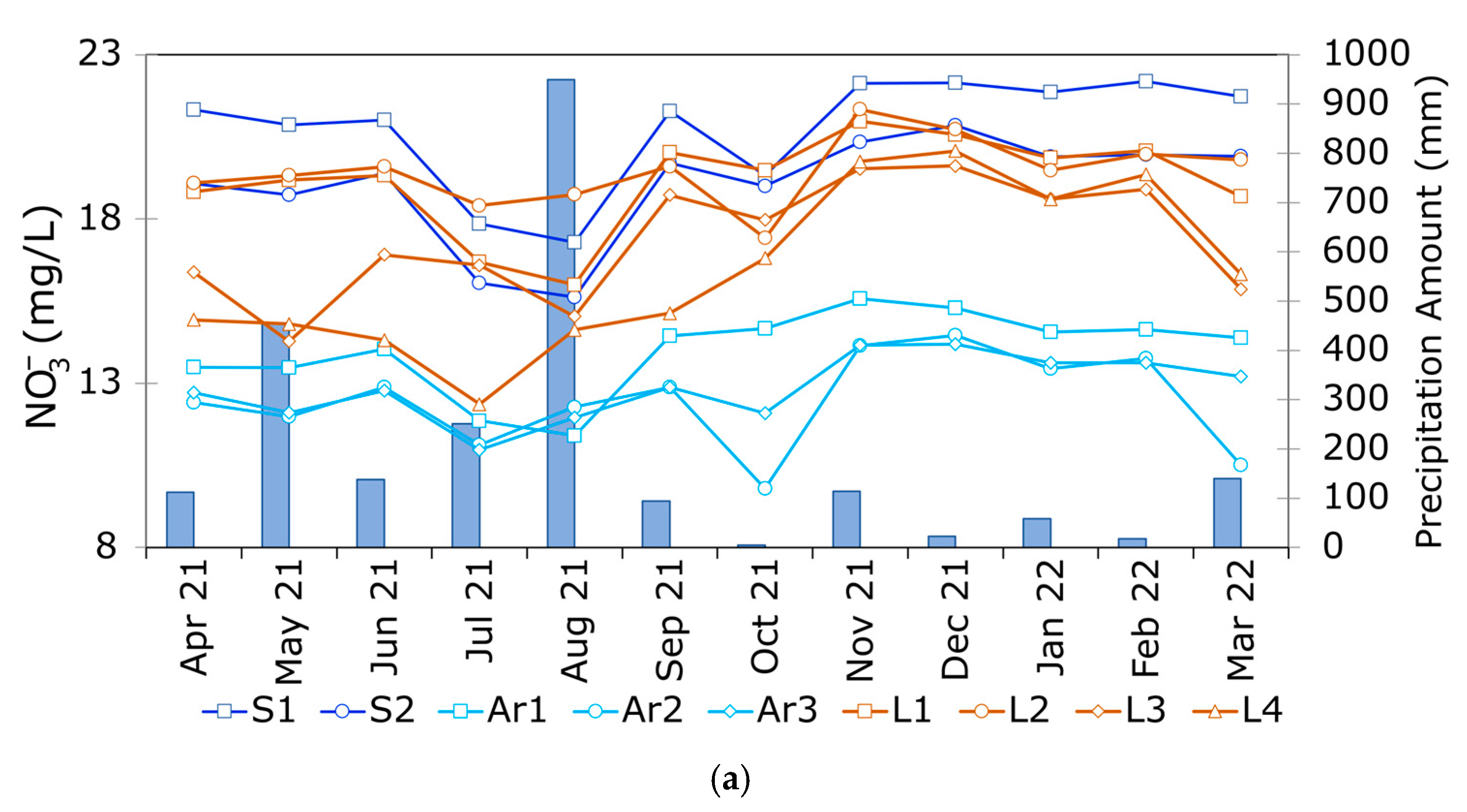

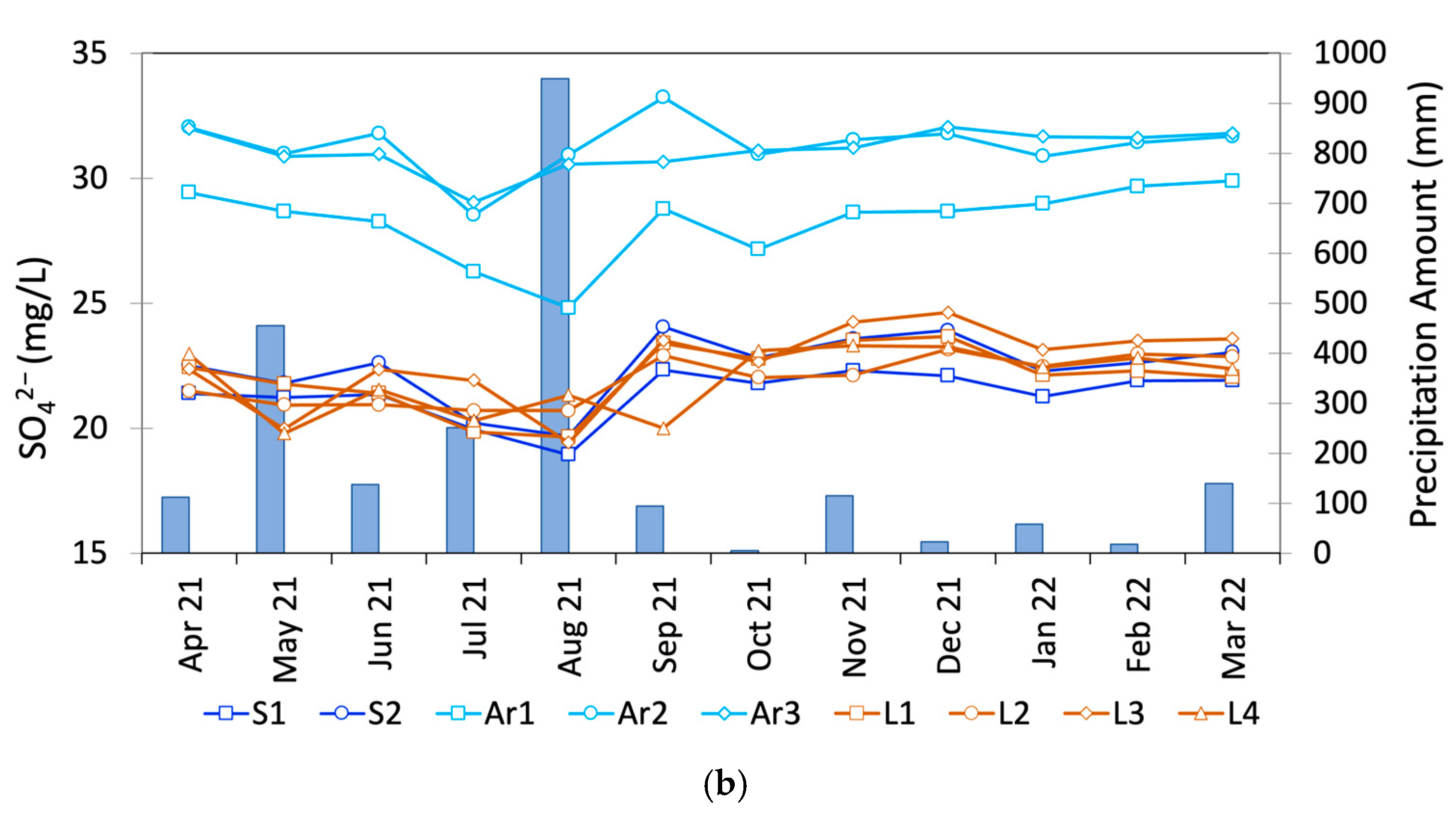

3.3. Seasonal Variations in the SO42− and NO3− Concentrations

4. Discussion

4.1. Sources of Groundwater Discharge Around Ezu Lake

4.2. Relationships with the Shallow and Deep Groundwaters

4.3. Contribution of the Shirakawa River Water to Ezu Lake

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tanaka, K.; Funakoshi, Y.; Hokamura, T.; Yamada, F. The Role of Paddy Rice in Recharging Urban Groundwater in the Shira River Basin. Paddy Water Environ. 2010, 8, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, S.; Ishii, T. Exploring the Origin and Flow of Groundwater from Water Quality—An Example from the Kumamoto Plain. Geol. News 1983, 349, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, M.; Tokunaga, T.; Shimada, J.; Ichiyanagi, K. Application of Continuous 222Rn Monitor with Dual Loop System in a Small Lake. Groundwater 2013, 51, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M.; Shimada, J.; Uemura, T. Transient Effects of Surface Temperature and Groundwater Flow on Subsurface Temperature in Kumamoto Plain, Japan. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2003, 28, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramaki, S. Studies on the Groundwater Conservation of KITAAMGI Spring Water in KASHIMA. 2002. Available online: https://kaken.nii.ac.jp/en/grant/KAKENHI-PROJECT-12680582/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Ichikawa, T. Flooding Project in Middle Shira-River area, KUMAMOTO. J. Groundw. Hydrol. 2022, 64, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Shimada, J.; Ichikawa, T.; Tokunaga, T. Evaluation of groundwater discharge in Lake Ezu, Kumamoto, based on radon in water. Jpn. J. Limnol. 2011, 72, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; Ichikawa, T. On the spring water characteristic and progress of nitrate nitrogen pollution of groundwater in the EZU-Lake, Kumamoto-city. Bull. Sch. Ind. Eng. Tokai Univ. 2012, 4, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, A.; Shimada, J.; Tanaka, T. Groundwater Flow System around the Takayubaru Upland Area at the South Western Foot of Aso Volcano. JAHS 1998, 28, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirohata, M.; Ozasa, Y.; Matsuzaki, T.; Fujita, I.; Matsuoka, R.; Watanabe, S. The Mechanism of Groundwater Pollution by Nitrate-nitrogen at U-town in Kumamoto Prefecture. J. Groundw. Hydrol. 1999, 41, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirohata, M.; Ozasa, Y. Water quality of the Kurokawa and Shirakawa Rivers. Annu. Rep. Kumamoto Prefect. Inst. Public Health Environ. Sci. 2005, 34, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hosono, T.; Tokunaga, T.; Kagabu, M.; Nakata, H.; Orishikida, T.; Lin, I.-T.; Shimada, J. The Use of δ15N and δ18O Tracers with an Understanding of Groundwater Flow Dynamics for Evaluating the Origins and Attenuation Mechanisms of Nitrate Pollution. Water Res. 2013, 47, 2661–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiie, K.; Itomitsu, N.; Matsuyama, K.; Kakimoto, R.; Kawagoshi, Y. Nitrate-Nitrogen Concentration in Groundwater of Kumamoto Urban Area and Determination of Its Contributors Using Geographical Information System and Nitrogen Stable Isotope Analysis. J. Jpn. Soc. Water Environ. 2010, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono, T.; Hossain, S.; Shimada, J. Hydrobiogeochemical Evolution along the Regional Groundwater Flow Systems in Volcanic Aquifers in Kumamoto, Japan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono, T.; Masaki, Y. Post-Seismic Hydrochemical Changes in Regional Groundwater Flow Systems in Response to the 2016 Mw 7.0 Kumamoto Earthquake. J. Hydrol. 2020, 580, 124340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Hosono, T.; Ohta, H.; Niidome, T.; Shimada, J.; Morimura, S. Comparison of Microbial Communities inside and Outside of a Denitrification Hotspot in Confined Groundwater. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 114, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, K.; Hosono, T.; Kagabu, M.; Fukamizu, K.; Tokunaga, T.; Shimada, J. Changes of Groundwater Flow Systems after the 2016 Mw 7.0 Kumamoto Earthquake Deduced by Stable Isotopic and CFC-12 Compositions of Natural Springs. J. Hydrol. 2020, 583, 124551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.T.M.S.; Kono, Y.; Hosono, T. Self-Organizing Map Improves Understanding on the Hydrochemical Processes in Aquifer Systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 846, 157281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono, T.; Taniguchi, K.; Sakiur Rahman, A.T.M.; Yamamoto, T.; Takayama, K.; Yu, Z.-Q.; Aihara, T.; Ikehara, T.; Amano, H.; Tanimizu, M.; et al. Stable N and O Isotopic Indicators Coupled with Social Data Analysis Revealed Long-Term Shift in the Cause of Groundwater Nitrate Pollution: Insights into Future Water Resource Management. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Yu, Z.-Q.; Berndtsson, R.; Hosono, T. Temporal Characteristics of Groundwater Chemistry Affected by the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake Using Self-Organizing Maps. J. Hydrol. 2020, 582, 124519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takehara, H.; Fukuda, T.; Sakaguchi, M.; Yoshida, F.; Tsuru, Y. Current Status and Secular Change of Water Quality in Lake Ezu; Kumamoto City Environmental Research Institute: Kumamoto, Japan, 2010; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikura, M. Nature of Lake Ezu. In Series of Natural Environment in Kumamoto; Kumamoto Biological Laboratory: Kumamoto, Japan, 1986; Volume 1, p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Christophersen, N.; Hooper, R.P. Multivariate Analysis of Stream Water Chemical Data: The Use of Principal Components Analysis for the End-Member Mixing Problem. Water Resour. Res. 1992, 28, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Meteorological Agency Japan Meteorological Agency. Historical Weather Data. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/view/monthly_s1.php?prec_no=86&block_no=47819&year=2021&month=11&day=&view=p1 (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Ichiyanagi, K.; Rahmawan, I.T.; Ide, K.; Shimada, J. Change in groundwater discharge rate around Lake Ezu before and after the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake. JAHS 2023, 53, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagabu, M.; Matsunaga, M.; Ide, K.; Momoshima, N.; Shimada, J. Groundwater Age Determination Using 85Kr and Multiple Age Tracers (SF6, CFCs, and 3H) to Elucidate Regional Groundwater Flow Systems. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2017, 12, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Meteorological Agency Japan Meteorological Agency. Search for Past Weather Data. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/index.php (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism National Land Information Download Site. Available online: https://nlftp.mlit.go.jp/ksj/gml/datalist/KsjTmplt-L03-b_r.html (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Ichiyanagi, K.; Ide, K.; Shimada, J.; Ichikawa, T. Re-consideration of the groundwater discharge rate around Lake Ezu, Kumamoto City. J. Jpn. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 2020, 50, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) | |||||||||

| ID | Annual M. | ||||||||

| A | B | C | |||||||

| Springs and artesian wells | |||||||||

| S1 | 57.4% | ± | 4.7% | 17.2% | ± | 0.9% | 25.4% | ± | 4.9% |

| S2 | 52.4% | ± | 4.5% | 20.2% | ± | 1.1% | 27.4% | ± | 5.4% |

| Ar1 | 37.3% | ± | 3.5% | 33.5% | ± | 1.9% | 29.2% | ± | 4.6% |

| Ar2 | 32.6% | ± | 4.1% | 39.6% | ± | 1.7% | 27.8% | ± | 4.0% |

| Ar3 | 33.7% | ± | 2.7% | 39.0% | ± | 0.9% | 27.3% | ± | 3.1% |

| Lake water | |||||||||

| L1 | 59.8% | ± | 6.0% | 20.7% | ± | 1.4% | 19.5% | ± | 7.2% |

| L2 | 70.8% | ± | 3.1% | 21.6% | ± | 1.6% | 7.7% | ± | 3.8% |

| L3 | 65.5% | ± | 5.4% | 21.9% | ± | 2.5% | 12.6% | ± | 7.5% |

| L4 | 57.5% | ± | 3.8% | 17.2% | ± | 2.8% | 25.3% | ± | 6.2% |

| (b) | |||||||||

| ID | Excluding July and August | ||||||||

| A | B | C | |||||||

| Springs and artesian wells | |||||||||

| S1 | 59.1% | ± | 2.5% | 17.4% | ± | 0.8% | 23.5% | ± | 2.1% |

| S2 | 54.2% | ± | 1.8% | 20.6% | ± | 0.9% | 25.3% | ± | 2.3% |

| Ar1 | 38.6% | ± | 2.0% | 34.0% | ± | 1.4% | 27.4% | ± | 1.7% |

| Ar2 | 33.0% | ± | 4.3% | 40.0% | ± | 1.4% | 27.0% | ± | 3.6% |

| Ar3 | 34.5% | ± | 2.1% | 39.2% | ± | 0.7% | 26.3% | ± | 2.1% |

| Lake water | |||||||||

| L1 | 61.7% | ± | 4.4% | 21.2% | ± | 1.2% | 19.0% | ± | 5.2% |

| L2 | 71.2% | ± | 3.3% | 21.8% | ± | 1.6% | 7.1% | ± | 3.9% |

| L3 | 64.1% | ± | 4.6% | 21.7% | ± | 2.7% | 14.2% | ± | 7.1% |

| L4 | 63.4% | ± | 3.8% | 21.5% | ± | 2.8% | 15.1% | ± | 6.1% |

| (c) | |||||||||

| ID | Only July and August | ||||||||

| A | B | C | |||||||

| Springs and artesian wells | |||||||||

| S1 | 48.5% | ± | 1.1% | 16.5% | ± | 0.9% | 35.1% | ± | 1.9% |

| S2 | 43.4% | ± | 0.8% | 18.6% | ± | 0.4% | 38.0% | ± | 1.2% |

| Ar1 | 30.8% | ± | 0.8% | 30.8% | ± | 1.4% | 38.4% | ± | 2.3% |

| Ar2 | 30.6% | ± | 2.2% | 37.6% | ± | 2.2% | 31.9% | ± | 4.3% |

| Ar3 | 29.9% | ± | 1.9% | 37.9% | ± | 1.2% | 32.2% | ± | 3.1% |

| Lake water | |||||||||

| L1 | 50.2% | ± | 0.8% | 18.7% | ± | 0.2% | 31.1% | ± | 0.6% |

| L2 | 68.8% | ± | 1.6% | 20.5% | ± | 0.0% | 10.8% | ± | 1.6% |

| L3 | 72.1% | ± | 4.1% | 23.3% | ± | 0.5% | 4.5% | ± | 3.5% |

| L4 | 60.6% | ± | 2.2% | 19.8% | ± | 1.4% | 19.6% | ± | 3.7% |

| Groundwater Type | Sample Counts | Well-Bottom Elevation (masl) | SO42− (mg/L) | NO3− (mg/L) | Calculated Mixing Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||||

| Shallow | 5 | −28–0 | 21.0–23.0 | 17.0–20.0 | 50.4–53.3% | 10.9–12.3% | 35.8–38.7% |

| Deep | 6 | −205–4 | 29.0–36.0 | 9.0–12.0 | 39.8–44.2% | 18.5–23.6% | 34.4–39.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahmawan, I.T.; Ichiyanagi, K.; Hamatake, H.; Basuki, I.N.; Nagaoka, T. Estimating the Groundwater Recharge Sources to Spring-Fed Lake Ezu, Kumamoto City, Japan from Hydrochemical Characteristics. Geosciences 2025, 15, 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120457

Rahmawan IT, Ichiyanagi K, Hamatake H, Basuki IN, Nagaoka T. Estimating the Groundwater Recharge Sources to Spring-Fed Lake Ezu, Kumamoto City, Japan from Hydrochemical Characteristics. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):457. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120457

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahmawan, Irfan Tsany, Kimpei Ichiyanagi, Haruchika Hamatake, Ilyas Nurfadhil Basuki, and Teru Nagaoka. 2025. "Estimating the Groundwater Recharge Sources to Spring-Fed Lake Ezu, Kumamoto City, Japan from Hydrochemical Characteristics" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120457

APA StyleRahmawan, I. T., Ichiyanagi, K., Hamatake, H., Basuki, I. N., & Nagaoka, T. (2025). Estimating the Groundwater Recharge Sources to Spring-Fed Lake Ezu, Kumamoto City, Japan from Hydrochemical Characteristics. Geosciences, 15(12), 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120457