Abstract

This paper aims to present, through a photographic reportage, the current state of rebuilding of the most devastated villages by the earthquake that hit the Southern Italy on 23 November 1980, in Irpinia-Basilicata. The earthquake was characterized by magnitude Ml = 6.9 and epicentral intensity I0 = X MCS. It was felt throughout Italy with the epicenter in the Southern Apennines, between the regions of Campania and Basilicata that were the most damaged areas. About 800 localities were serious damaged; 7,500 houses were completely destroyed and 27,500 seriously damaged. The photographic survey has been done in 23 towns during the last five years: Castelnuovo di Conza, Conza della Campania, Laviano, Lioni, Santomenna, Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi, Balvano, Caposele, Calabritto and the hamlet of Quaglietta, San Mango sul Calore, San Michele di Serino, Pescopagano, Guardia dei Lombardi, Torella dei Lombardi, Colliano, Romagnano al Monte, Salvitelle, Senerchia, Teora, Bisaccia, Calitri and Avellino. Forty years after the 1980 earthquake, the photographs show villages almost completely rebuilt with modern techniques where reinforced concrete prevails. Only in few instances, the reconstruction was carried out trying to recover the pre-existing building heritage, without changing the original urban planning, or modifying it. We argue that this photography collection allows to assess the real understanding of the geological information for urban planning after a major destructive seismic event. Even more than this, documenting the rebuilding process in a large epicentral area reveals the human legacy to the natural landscape, and our ability, or failure, to properly interpret the environmental fate of a site.

1. Introduction

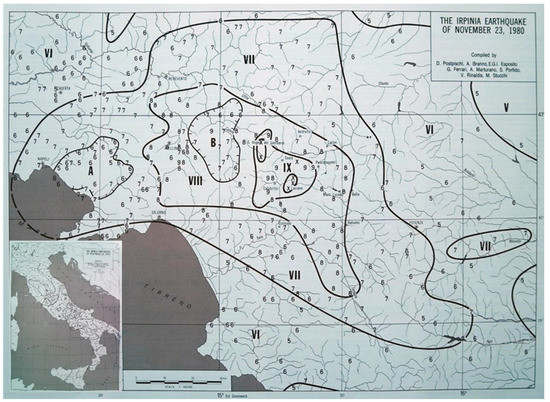

The earthquake of 23 November 1980, more commonly known as the Irpinia-Basilicata earthquake, was the strongest seismic event to hit the Southern Apennines in the last 100 years. It was characterized by magnitude Mw = 6.9 and intensity Io = X Mercalli Cancani Sieberg (MCS) scale and/or X Environmental Seismic Intensity 2007 (ESI-07) scale [1,2,3,4]. It was felt throughout Italy, from Sicily in the South, to Emilia Romagna and Liguria in the North (Figure 1). It caused devastating effects in over 800 localities distributed in the regions of Campania and Basilicata with a total of 75,000 houses destroyed and 275,000 seriously damaged. The number of victims was about 3000, with 10,000 injured people. Several municipalities distributed in the provinces of Avellino, Salerno and Potenza were almost totally destroyed, since the local felt intensity was I > VIII MCS. In the Campania region, the level of damage of 542 towns was classified as follows: 28 towns destroyed, 250 seriously damaged, 264 damaged; in the Basilicata region, 131 municipalities were classified of which nine were destroyed, 63 seriously damaged and 59 damaged [5,6,7].

Figure 1.

Isoseismal Map of the 23 November 1980 Irpinia-Basilicata earthquake [1].

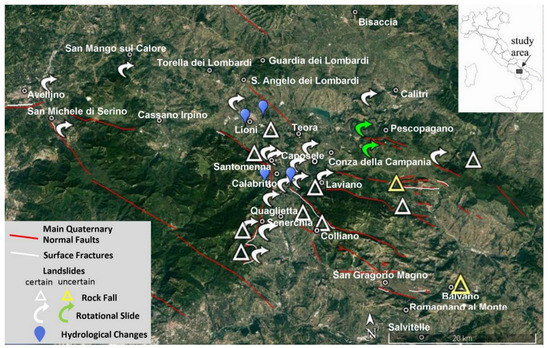

The earthquake also caused several striking effects on the natural environment including extensive coseismic surface faulting, observed between Lioni (Avellino) and San Gregorio Magno (Salerno) [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Moreover, over 200 landslides occurred, the most devasting hit the territories of Calitri in the urban center [11,19,20,21,22], Caposele (Buoninventre landslide) and Senerchia (Serra d’Acquara landslide) (Figure 2) [11,23]; also, widespread soil fracturing was observed, and minor liquefaction effects [24,25,26,27]. Furthermore, the coseismic faulting of the regional karst aquifer induced important hydrological variations in the springs of Caposele and Cassano Irpino [25] (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Environmental effects induced in the epicentral area by the 23 November 1980 Irpinia-Basilicata earthquake [21]. The Ortophoto image from Google Earth.

Table 1.

The table contains the visited localities, their geographic coordinates and MCS and ESI intensity with the most significant environmental effects observed after the 1980 earthquake (SF surface fault; F fractures, L landslide, SC Soil Compaction, HC Hydrological Changes, LQ Liquefaction) [1,2,3,11,12,14,19,20,21,22,23,25,26,27].

Forty years after the 1980 earthquake, we decided to record, through a photographic reportage, the state of the rebuilding, the urban changes that the earthquake had induced mainly in the epicenter and near field areas. This study represents a realistic documentation of what has been achieved over all these years, even with the considerable state economic funding, and the resilience of each community [28]. The study of the various localities portrayed is accompanied by a detailed bibliography starting from 1981 until today.

2. Discussion

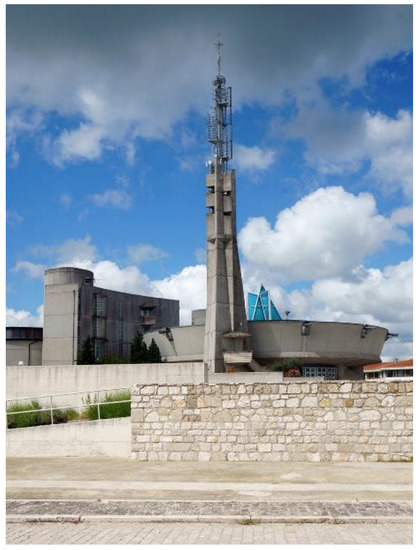

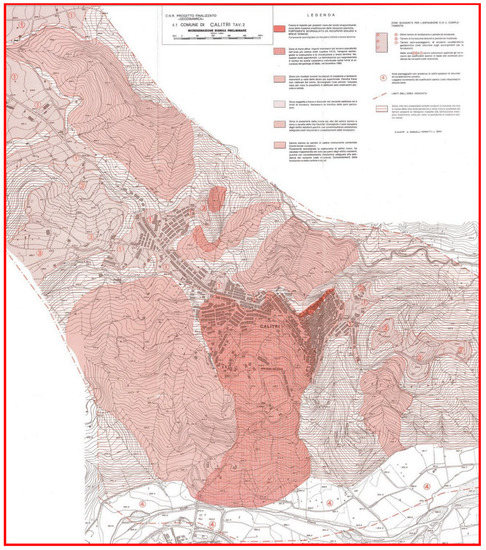

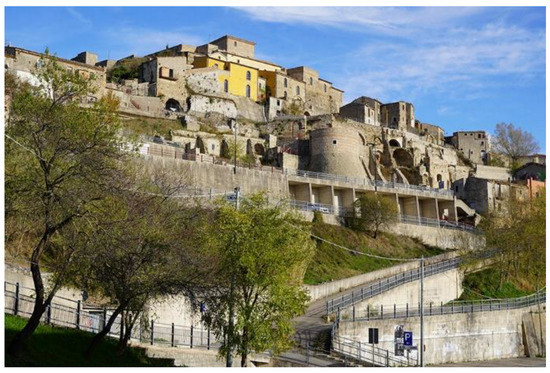

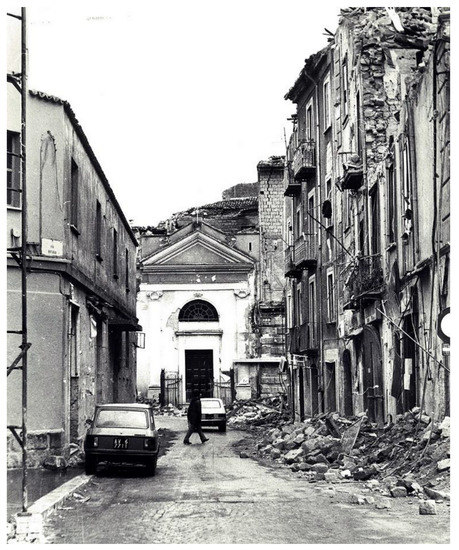

The photographic journey, carried out in the last five years, includes the documentation of the villages almost completely destroyed or seriously damaged (Figure 3), with damage levels evaluated at I ≥ VIII MCS, Table 1): Castelnuovo di Conza (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9), Conza della Campania (Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18), Laviano (Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22), Lioni (Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27 and Figure 28), Santomenna (Figure 29, Figure 30, Figure 31, Figure 32 and Figure 33), Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi (Figure 34, Figure 35, Figure 36, Figure 37, Figure 38 and Figure 39), Balvano (Figure 40, Figure 41, Figure 42 and Figure 43), Caposele (Figure 44, Figure 45, Figure 46 and Figure 47), Calabritto-Quaglietta (Figure 48, Figure 49, Figure 50, Figure 51, Figure 52 and Figure 53), San Mango sul Calore (Figure 54, Figure 55, Figure 56, Figure 57 and Figure 58), San Michele di Serino (Figure 59, Figure 60, Figure 61, Figure 62, Figure 63, Figure 64 and Figure 65), Pescopagano (Figure 66, Figure 67, Figure 68, Figure 69 and Figure 70), Guardia dei Lombardi (Figure 71, Figure 72, Figure 73 and Figure 74), Torella dei Lombardi (Figure 75, Figure 76, Figure 77, Figure 78 and Figure 79), Colliano (Figure 80, Figure 81, Figure 82, Figure 83, Figure 84 and Figure 85), Romagnano al Monte (Figure 86, Figure 87, Figure 88 and Figure 89), Salvitelle (Figure 90, Figure 91, Figure 92, Figure 93 and Figure 94), Senerchia (Figure 95, Figure 96, Figure 97, Figure 98 and Figure 99) and Teora (Figure 100, Figure 101, Figure 102, Figure 103 and Figure 104) [1,2,4,7,29]. In some cases, we also took into account the preliminary seismic microzonation maps drawn up by the PFG of CNR (Finalized Geodynamic Project (PFG) of the National Research Council (CNR), the first major national project for seismic risk assessment and reduction), which provided useful indications for reconstruction [29]. Moreover, two others towns, Bisaccia (Figure 105, Figure 106, Figure 107 and Figure 108) and Calitri (Figure 109, Figure 110, Figure 111, Figure 112, Figure 113 and Figure 114), although characterized by a lower intensity (I = VIII MCS), have been added to our study due to the different pathways for reconstruction, despite having both serious hydrogeological problems. Bisaccia has been often affected by landslides, due to its geological formations, mostly made by conglomerates resting on varicolored clays; indeed it was among the villages admitted to consolidation as early as 1917. Nowadays there are two Bisaccia villages: the old, ancient village recovered around the ducal castle and the new Bisaccia of the ‘Piano di Zona’, the latter almost completely rebuilt according to the urban plan drawn up by the architect Aldo Loris Rossi. Regards Calitri, it was built on the top of a hill made of sandstone and conglomerate rocks, with the middle-lower slopes made of intensely tectonized clay-rich units; therefore, it was often affected by landslides. A great landslide occurred due to the 1980 earthquake, approximately 850 m long and up to 100 m deep; it had terrible consequences on the urban and road structure of the village [19]. Moreover, other significant coseismic environmental effects occurred such as fracturing and liquefaction phenomena. Further landslides occurred in Calitri due to the 1694, 1805, 1910 and 1930 earthquakes [1,7,11,21,22,29,30,31]. We also added the Avellino city (Figure 115, Figure 116, Figure 117, Figure 118 and Figure 119), because it is one of the largest cities in Campania, with level of damage I = VIII [32].

Figure 3.

The front page of “Il Mattino” newspaper (26 November 1980) transformed by Andy Warhol into a pop art manifesto [33].

Figure 4.

Original map of the seismic microzonation of Castelnuovo di Conza according to [29].

Figure 5.

Castelnuovo di Conza: overview of the new village completely rebuilt after the1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 6.

Castelnuovo di Conza: detail of the new village completely rebuilt after the1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 7.

Castelnuovo di Conza: the new sports hall (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 8.

Castelnuovo di Conza: Temporary village, consisting of wooden chalets, built immediately after the 1980 earthquake and still used today (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 9.

Castelnuovo di Conza: detail of new reinforced concrete buildings (photos by [35,36]).

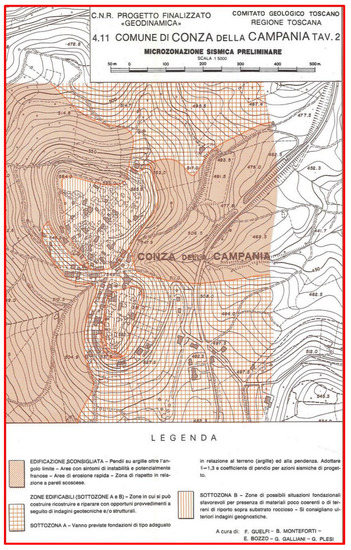

Figure 10.

Original map of the seismic microzonation of Conza della Campania according to [29].

Figure 11.

Conza della Campania: overview of the old village destroyed by the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

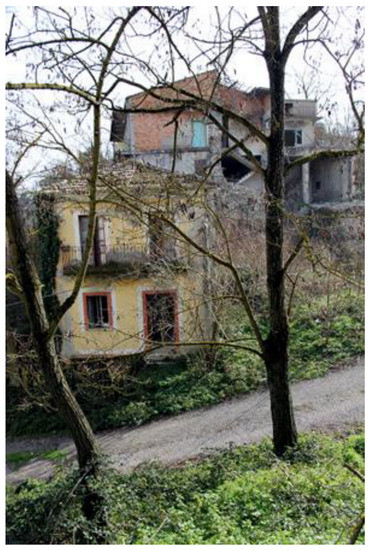

Figure 12.

Conza della Campania: old village with ruins of houses after the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 13.

Conza della Campania: old village with houses rebuilt after the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 14.

Conza della Campania: old village with the Archaeological Park realized a few years ago for the tourists (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 15.

Conza della Campania: detail of the Archaeological Park (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 16.

Conza della Campania: temporary village, consisting of wooden housing, built immediately after the earthquake of 1980 and now almost completely abandoned (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 17.

Conza della Campania: new village with the new Cathedral “Concattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta” in the center of village built after the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 18.

Conza della Campania: panoramic view of the new Conza built in Piano delle Briglie locality, 4 km far from the original nucleus of the old Conza (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 19.

Laviano: the village completely rebuilt after the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 20.

Laviano: the new “Chiesa Madre” (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 21.

Laviano: the new Town Hall of Laviano (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 22.

Laviano: Piazza della Repubblica (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 23.

Lioni: one of the first buildings built in 1985, the “Bergamo condominium” is in reinforced concrete, built thanks to the solidarity of the inhabitants of Bergamo (Northern Italy) (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 24.

Lioni: a detail of the “Bergamo condominium”, the recent murales was done to remember the solidarity of the people forty years after the catastrophic earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 25.

Lioni: part of modern Town Hall built by the architect A. Verderosa (1984–1994) (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 26.

Lioni: modern bus station (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 27.

Lioni: the new sports facilities (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 28.

Lioni: restored Church and bell tower of S. Maria Assunta (photos by [35,36]).

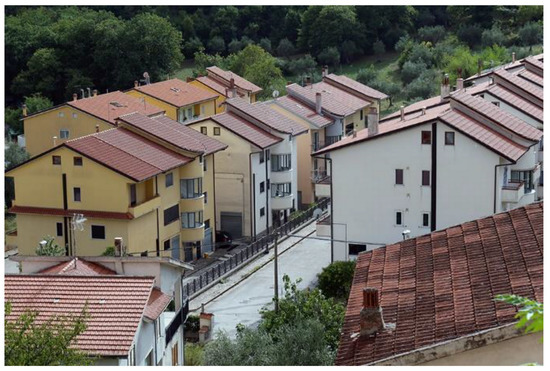

Figure 29.

Santomenna: overview of the village completely rebuilt (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 30.

Santomenna: the center of the village completely rebuilt (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 31.

Santomenna: a detail of the new buildings (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 32.

Santomenna: the new Town Hall in reinforced concrete (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 33.

Santomenna: S. Maria delle Grazie church (photos by [35,36]).

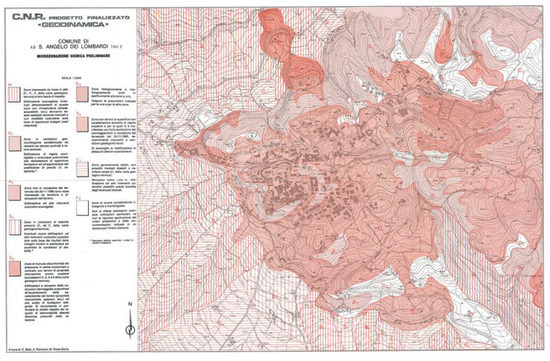

Figure 34.

Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi: original map of the seismic microzonation according to [29].

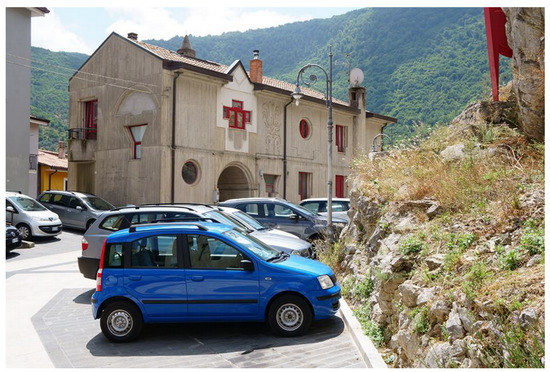

Figure 35.

Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi: the historical center with the Town Hall, reconstructed taking into account the original urban design (photos by [35,36]).

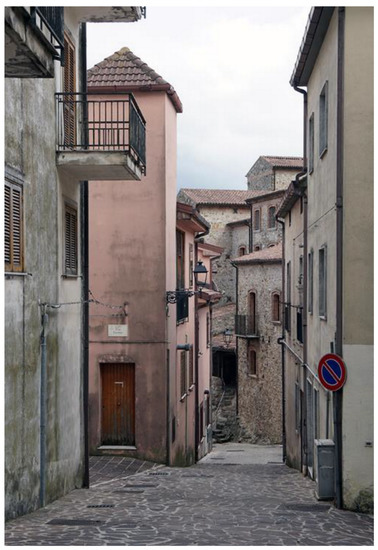

Figure 36.

Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi: the remains of the Goleto Abbey (photos by [35,36]).

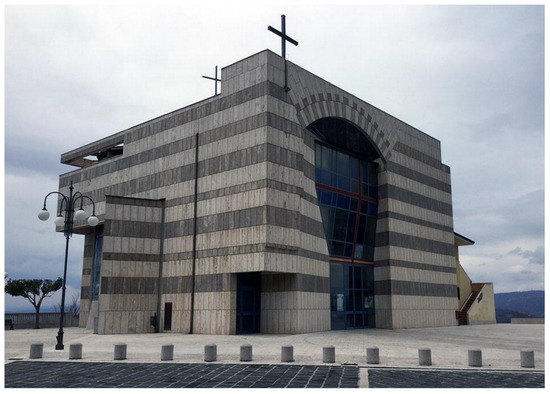

Figure 37.

Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi: Archdiocese of Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi in the historical center: (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 38.

Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi: Castle of the Imperials of Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi in the Historical center (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 39.

Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi: overview of new buildings and the football field (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 40.

Balvano: Panoramic view with the Castle in the foreground (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 41.

Balvano: overview of new buildings (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 42.

Balvano: the new buildings details of the architecture by R. Boffo and K. Eibl (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 43.

Balvano: the new buildings details of the architecture by R. Boffo and K. Eibl (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 44.

Caposele: the Town Hall in the historical center (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 45.

Caposele: the historical center with the new buildings reconstructed taking into account the original urban design (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 46.

Caposele: the historical center with the new buildings reconstructed taking into account the original urban design (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 47.

Caposele: the historical center with artistic murals (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 48.

Calabritto: panoramic view of the village completely rebuilt (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 49.

Calabritto: The new Church of Santissima Trinità (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 50.

Calabritto: “Largo 23 November 1980”—Memorial dedicated to the earthquake victims (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 51.

Quaglietta: Panoramic view of the castle and its medieval village completely restored after the 1980 hearthquake. Currently the medieval village is a tourist attraction as “albergo diffuso” (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 52.

Quaglietta: detail of the medieval village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 53.

Quaglietta: detail of the medieval village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 54.

Original map of the seismic microzonation of San Mango sul Calore according to [29].

Figure 55.

San Mango sul Calore: Panoramic view of the village completely rebuilt after the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 56.

San Mango sul Calore: the new Church of Santa Maria degli Angeli (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 57.

San Mango sul Calore: “villaggio italo-canadese” new homes built with the help of Canadians (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 58.

San Mango sul Calore: “Villaggio S. Stefano”. Temporary village, consisting of wooden chalets, built immediately after the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

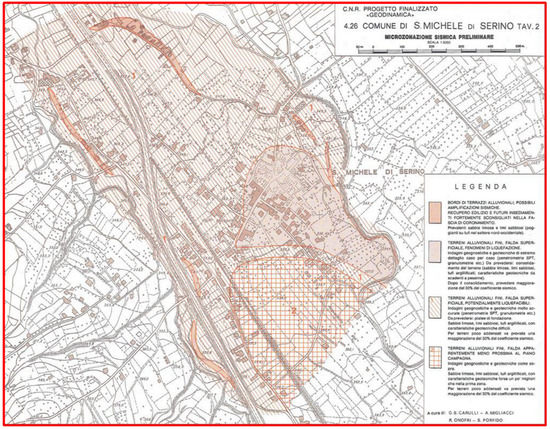

Figure 59.

Original map of the seismic microzonation of San Michele di Serino according to [29].

Figure 60.

San Michele di Serino: “Mariconda” palace facade, one of the few historical facades not destroyed by the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

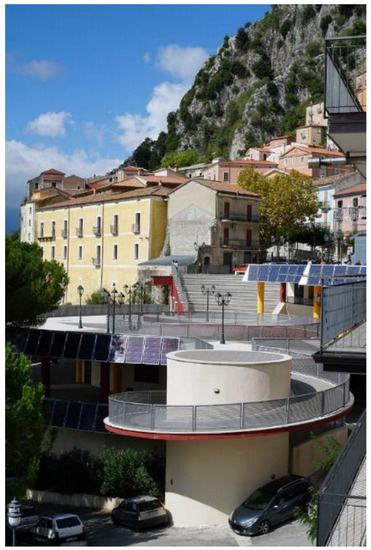

Figure 61.

San Michele di Serino: the new municipal building (photos by [35,36]).

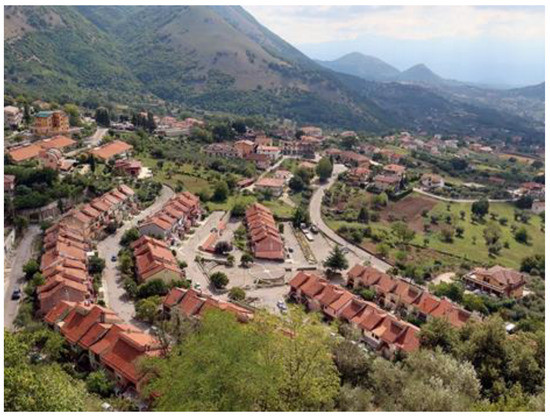

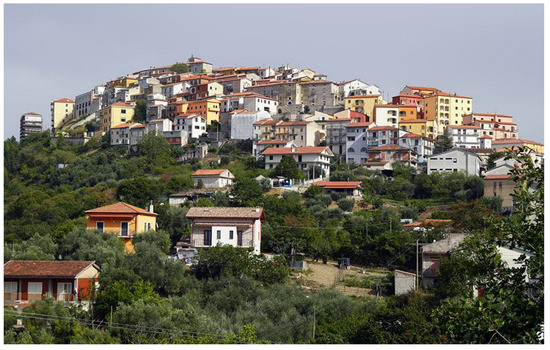

Figure 62.

San Michele di Serino: new reinforced concrete buildings (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 63.

San Michele di Serino: the new Church of San Michele Arcangelo (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 64.

San Michele di Serino: the monument to the victims of the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 65.

San Michele di Serino: detail of Cotone Street in which there were phenomena liquefaction triggered by the earthquake [22], (photos by [35,36]).

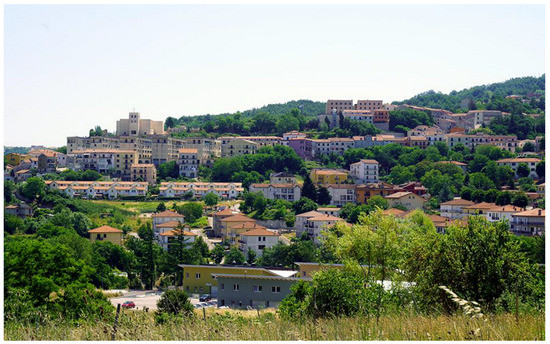

Figure 66.

Pescopagano: a panoramic view of the new village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 67.

Pescopagano: panoramic view of a part of village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 68.

Pescopagano: the new Town Hall of village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 69.

Pescopagano: “Porta della Sibilla” into the historical centre (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 70.

Pescopagano: ruins of the medieval castle (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 71.

Guardia dei Lombardi: panoramic view of the new village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 72.

Guardia dei Lombardi: the restored Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 73.

Guardia dei Lombardi: the restored historical centre (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 74.

Guardia dei Lombardi: the new Town Hall of village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 75.

Torella dei Lombardi: the restored castle of Ruspoli di Candriano (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 76.

Torella dei Lombardi: the new Church of S. Maria del Popolo (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 77.

Torella dei Lombardi: stone plaque to remember the victims of the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 78.

Torella dei Lombardi: details of the new buildings (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 79.

Torella dei Lombardi: details of the new buildings (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 80.

Colliano: the new Town Hall of the village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 81.

Colliano: modern access structure with lift to Piazza Epifani (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 82.

Colliano: New parking area of the Epifani Square (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 83.

Colliano: New Epifani Square (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 84.

Colliano: detail of the restored historical centre (Church of Santa Maria del Borgo) (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 85.

Colliano: new residential settlement known as “Piano di zona” (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 86.

Romagnano al Monte: panoramic view of the village, completely abandoned after 1980 earthquake, now ghost town (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 87.

Romagnano al Monte: details of the old village completely abandoned after 1980 earthquake, (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 88.

Romagnano al Monte: the Church of Maria SS. del Rosario in the new town, located in Ariola, 2 km from the old center (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 89.

Romagnano al Monte: details of new buildings in the new town (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 90.

Salvitelle: Panoramic view of the new village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 91.

Salvitelle: the new Town Hall of the village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 92.

Salvitelle: new buildings mainly in reinforced concrete (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 93.

Salvitelle: details of new buildings (photos by [35,36]).

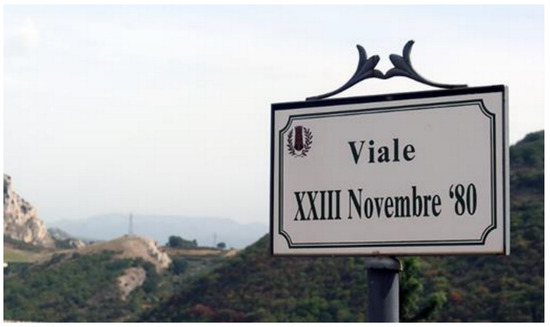

Figure 94.

Salvitelle: plaque of a new street that remember the earthquake of 23 November 1980 (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 95.

Senerchia: Overview of the remains of the old village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 96.

Senerchia: a small street of the old village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 97.

Senerchia: the new village, “Piazza 23 Novembre 1980” and monument dedicated to the earthquake victims (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 98.

Senerchia: details of the new buildings (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 99.

Senerchia: new school complex (photos by [35,36]).

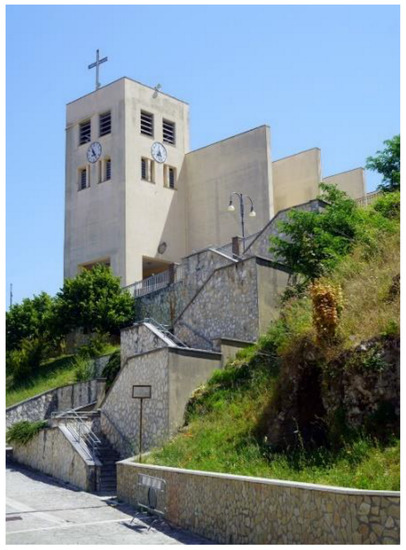

Figure 100.

Teora: panorama of the reconstructed village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 101.

Teora: the new Church of S. Nicola di Mira (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 102.

Teora: new school complex and Town Hall (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 103.

Teora: part of the restored historical centre (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 104.

Teora: new reinforced concrete houses (photos by [35,36].

Figure 105.

Bisaccia: the new village (Piano di Zona) with new Church of Sacro Cuore built by the architect A. L. Rossi, 1998 (photos by [41]).

Figure 106.

Bisaccia: the new village (Piano di Zona) with a details of some reinforced concrete buildings realized by architect A. L. Rossi, (photos by [41]).

Figure 107.

Bisaccia: the new village (Piano di Zona) with a detail of the new reinforced concrete homes designed by the architect A. L. Rossi, (photos by [41]).

Figure 108.

Bisaccia: the new village (Piano di Zona) with the remains of the new social housing still to be completed (Istituto Autonomo Case Popolari-IACP). A part of them has been demolished in 2020 (photos by [41]).

Figure 109.

Calitri: panoramic view of the village (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 110.

Original map of the seismic microzonation of Calitri according to [29].

Figure 111.

Calitri: historical centre, remains of some buildings that were recovered after the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 112.

Calitri: historical centre, remains of some buildings that were recovered after the 1980 earthquake (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 113.

Calitri: panoramic view of new buildings (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 114.

Calitri: panoramic view of the new constructions, the historical centre and the remains of the castle on the hill (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 115.

Avellino: panoramic view of the town (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 116.

Avellino: Rifugio Street after 1980 earthquake (cortesy of F. Capossela).

Figure 117.

Avellino: Rifugio Street today completely reconstructed (photos by [35,36]).

Figure 118.

Avellino: “Piazza del popolo” after the 1980 earthquake (courtesy of F. Capossela).

Figure 119.

Avellino: “Piazza del Popolo” today completely reconstructed (photos by [35,36]).

In this photographic reportage, we have deliberately chosen not to reproduce the tragic images of the catastrophe, destruction, death of the places visited, that characterized all the front pages of the newspapers of the time (e.g., Figure 3) [33]. We have chosen to show the current, rebuilt urban centers.

We analyzed the reconstruction through the representative buildings as the churches, the town halls, the sports centers. In some cases, there are pictures of temporary villages, generally made of wooden houses, where people lived for many years waiting for the final accommodation, now used for local tourism. Almost all the villages were rebuilt in the same place despite some of them were completely razed to the ground not only by the earthquake but also by bulldozers that destroyed everything, even more than necessary.

The buildings of the old urban centers were mostly made in natural stone or baked bricks with poor mortar and wooden floors while the rebuilding involved reinforced concrete buildings, earthquake-proof. The new urban centers were rebuilt with wide roads and outsized areas for new housing compared to the current number of inhabitants, that over the last forty years has decreased dramatically, especially for the most internal areas.

As mentioned above, all of the villages affected by the earthquake were rebuilt in situ, with the exception of Conza della Campania, Romagnano al Monte and Bisaccia. For Conza della Campania, a town almost completely destroyed by the earthquake with a high number of deaths (184 victims), the political choice of the urban center relocation prevailed, supported also by the results of the numerous geological surveys some of which also emphasized local amplification phenomena due to morphology. Indeed, Conza was built on two small hills made by clay and sandy clay in the lower part, conglomerates with sands and sandstones in the middle part, and conglomerates of middle-low resistance in the upper part. The 1980 earthquake induced in this village several different environmental effects such as landslides, ground cracks and ground settlement. Moreover, this choice was also due to the historical memory of the destruction suffered by the community in past earthquakes (1466, 1517,1694, 1732 and 1930 seismic events) [7,18,29,30,31,34]. At present two Conza villages f coexist: the ancient village recovered and enhanced with the creation of an archaeological park that preserves the remains of the ancient Roman ‘Compsa’; and the new Conza, built in Piano delle Briglie, 4 km far from the original nucleus where the topography of this flat area ensured safer conditions. This is a modern village characterized by earthquake-proof houses and wide roads, designed by the architect Beguinot of the University of Naples, [35,36,37,38].

Even for Romagnano al Monte, a small village in the Salerno province with only 370 inhabitants, located 650 m a.s.l., overlooking the gorges of the Platano River, a few kilometres from the epicentre of the 1980 earthquake, the political decision to relocate prevailed. The main reason was due to the declared inhabitability of 446 residential units, after the earthquake, that also caused the collapse of some churches and heavy damage to the town hall. The geomorphological and geological assessment, that accentuated the seismic shaking, also contributed to the choice in the reconstruction process. The old town, in fact, is located at the highest point on the ridge and along the slopes are frequent phenomena of rock fall caused by the high degree of fracturing bedrock.

The village was evacuated and abandoned becoming a “ghost town” [39]. The new town was located in Ariola, 2 km from the old center, in a less panoramic position, but providing more convenient access for the inhabitants.

More complex and longer is the history of Bisaccia’s relocation. The village located at 860 m a.s.l., was affected by landslides due to the geological conditions on which it stands and was already destroyed by historical earthquakes (1694 1732, 1930 and 1980 seismic events). These aspects have heavily conditioned its rebuilding. The 1980 earthquake, once again highlighted the territory’s extremely unstable conditions, so the Municipal Administrations opted for the reconstruction of the village in another site, more stable from a geological point of view, called “Piano di Zona”, which was already identified in a previous urban planning, following the 1930 earthquake [7,40,41].

As a matter of fact, there are currently two Bisaccia towns: the old one, an ancient village recovered around the ducal castle; and the new Bisaccia of the Piano di Zona, the latter almost completely rebuilt according to the urban planning drawn up by architect Aldo Loris Rossi [42].

About the other villages we can say that among those among those which have decided to rebuild in situ, some of them have chosen the recovery or rebuilding of the old urban center, respecting the original architectural design, combined with new buildings in the expansion areas.

Among these we mention certainly Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi, with a careful reconstruction of the historical centre and the Abbey of Goleto (Figure 36) [7,29,31,43]; Calitri despite the historical large landslide triggered by the earthquakes (Figure 110) [7,29]; Guardia dei Lombardi (Figure 73) [7,29]; Torella dei Lombardi [7,29];(Figure 75); Caposele [29,34]; Lioni (Figure 28); Balvano (Figure 41); Pescopagano (Figure 66); and Quaglietta (Figure 53), whose medieval village has been recovered to transform it into an “albergo diffuso” (“scattered hotel”) for tourism purposes [34,44].

Even Senerchia, which has been currently rebuilt, tries to recover the remaining houses of the ancient village built on the solid calcareous substratum (Figure 98) [7,29,34]. In all the other villages the new buildings are predominant with some valuable innovative edifices such as the town hall of Lioni (Figure 25), a modern and functional building realized by the architect Verderosa, or in Balvano where the artists Boffo and Eibl designed the houses, or architectural structures often in contrast with the original planning of the village (Figure 42 and Figure 43).

Unfortunately, in many cases during the rebuilding process the identity of Apennine villages such as Laviano (Figure 19 and Figure 22), San Michele di Serino (Figure 62), Castelnuovo di Conza (Figure 5), Santomenna (Figure 30), where the new buildings prevail over the old ones, was lost, becoming only “rebuilt villages”.

3. Conclusions

The rebuilding process, in many localities, has been driven by microzonation maps drawn up as part of the Finalized Geodynamic Project (PFG) of the National Research Council (CNR), created immediately after the 1980 earthquake [29].

The seismic microzonation maps show the areas with different seismic characteristics, illustrating the morphological structure of the territory, the distribution of the building heritage existing in 1980, and in some cases, the level of damage suffered due the 1980 event and provide suggestions for reconstruction. We reported some examples of these maps: Castelnuovo di Conza (Figure 4), Conza della Campania (Figure 11), S. Angelo dei Lombardi (Figure 34), San Mango sul Calore (Figure 55), San Michele di Serino (Figure 60), Calitri (Figure 110).

However, the choices made for the reconstruction did not depend only on the geological assessment of the territory and therefore on the indications given by the microzoning maps, but also on the urban and socio-economic context. Nevertheless, there has not been a socio-economic redevelopment policy for the entire territory which, despite the settlement of some important factories, is currently suffering from unemployment and depopulation [45,46,47,48,49].

Our reportage is certainly not exhaustive, in fact there are still many other places that have undergone considerable transformations during the reconstruction process. The images can guide the future urban development of ancient villages after a major destructive seismic event, with a view to safeguarding the territory and cultural heritage. Even more than this, documenting the rebuilding process in a large epicentral area reveals the human legacy to the natural landscape, and our ability, or failure, to properly interpret the environmental fate of a site. Often in the post-earthquake reconstruction process of 1980, instead of taking into accounts the socio-economic, historical and geological local conditions, different case by case for each affected village, the policy of rebuilding at any cost has prevailed, even with buildings unsuitable for the context of the Apennine inland areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and E.S.; methodology, S.P.; software, R.N.; validation, R.N., G.A., G.G., E.S., A.M.M. and S.P.; formal analysis, S.P., E.S.; investigation, G.G., G.A.; resources, R.N.; data curation, R.N., G.G., G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., G.G., R.N., A.M.M. and G.A.; writing—review and editing, R.N., G.G., G.A., A.M.M.; visualization, A.M.M.; supervision, S.P.; project administration, E.S., S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is dedicated to all the inhabitants of these villages who experienced the terrible earthquake of 1980, but nevertheless have been able to recover with great dignity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Postpischl, D.; Branno, A.; Esposito, E.; Ferrari, G.; Marturano, A.; Porfido, S.; Rinaldis, V.; Stucchi, M. The Irpinia earthquake of November 23, 1980. In Atlas of Isoseismal Maps of Italian Earthquakes; CNR-PFG: Bologna, Italy, 1985; Volume 114, pp. 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Rovida, A.; Locati, M.; Camassi, R.; Lolli, B.; Gasperini, P. CPTI15, the 2015 Version of the Parametric Catalogue of Italian Earthquakes. INGV 2016. [CrossRef]

- Serva, L.; Esposito, E.; Guerrieri, L.; Porfido, S.; Vittori, E.; Comerci, V. Environmental Effects from some historical earthquakes in Southern Apennines (Italy) and macroseismic intensity assessment. Contribution to INQUA EEE scale project. Quat. Int. 2007, 173–174, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizzi, F.T.; Potenza, M.R. The scientific landscape of November 23rd, 1980 Irpinia Basilicata earthquake: Taking stock of (almost) forty years of studies. Geosciences 2020, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commissione Parlamentare d’Inchiesta Sulla Attuazione Degli Interventi per la Ricostruzione e lo Sviluppo dei Territori della Basilicata e della Campania Colpiti dai Terremoti del Novembre 1980 e Febbraio 1981. Relazione Conclusiva e Propositiva. 1991, Volume I. Available online: https://storia.camera.it/lavori/sedute/27-novembre-1990-bf-10-19901127-00-01 (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Proietti, G. “Dopo la Polvere”. Rilevazione Degli Interventi di Recupero Post-Sismico del Patrimonio Archeologico, Architettonico ed Artistico delle Regioni Campania e Basilicata Danneggiato dal Terremoto del 23 Novembre 1980 e del 14 Febbraio 1981; Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali: Rome, Italy, 1994; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, D.; Sepe, M. (Eds.) Rischio Sismico, Paesaggio, Architettura: L’Irpinia Contributi per un Progetto; CRdC AMRA: Naples, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bollettinari, G.; Panizza, M. Una faglia di superficie presso San Gregorio Magno in occasione del sisma del 23/11/1980 in Irpinia. Rend. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1981, 4, 135–136. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, A.; Lambiase, S.; Sgrosso, I. Su due faglie nell’alta valle del Sele legate al terremoto del 23.11.1980. Rend. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1981, 4, 127–129. [Google Scholar]

- Carmignani, L.; Cello, G.; Cerrina Feroni, A.; Funiciello, R.; Klin, O.; Meccheri, M.; Patacca, E.; Pertusati, P.; Plesi, G.; Salvini, F.; et al. Analisi del campo di fratturazione superficiale indotto dal terremoto Campano-Lucano del 23/11/1980. Rend. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1981, 4, 451–465. [Google Scholar]

- Cotecchia, V. Ground deformations and slope instability produced by the earthquake of 23 November 1980 in Campania and Basilicata. Geol. Appl. Idrogeol. 1986, 21, 31–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pantosti, D.; Valensise, G. Faulting mechanism and complexity of the November 23, 1980, Campania-Lucania earthquake, inferred from surface observations. J. Geophys. Res. 1990, 95, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaway, R.; Jackson, J. Surface faulting in the southern Italian Campania-Basilicata earthquake of 23 November 1980. Nature 1984, 312, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumetti, A.M.; Esposito, E.; Ferreli, L.; Michetti, A.M.; Porfido, S.; Serva, L.; Vittori, E. Ground effects of the 1980 Irpinia earthquake revisited: Evidence for surface faulting near Muro Lucano. In Large-Scale Vertical Movements and Related Gravitational Processes; Dramis, F., Farabollini, P., Molin, P., Eds.; Studi Geol. Camerti: Camerino, Italy, 2002; pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, P.; Zollo, A. The Irpinia (Italy) 1980 earthquake: Detailed analysis of a complex normal faulting. J. Geophys. Res. 1989, 94, 1631–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, A.; Mazzoli, S.; Petrosino, P.; Valente, E. A decoupled kinematic model for active normal faults: Insights from the 1980, MS = 6.9 Irpinia earthquake, southern Italy. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2013, 125, 1239–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, P. Roman to Middle Age Earthquakes Sourced by the 1980 Irpinia Fault: Historical, Archaeoseismological, and Paleoseismological Hints. Geosciences 2020, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matano, F.; Di Nocera, S.; Criniti, S.; Critelli, S. Geology of the Epicentral Area of the November 23, 1980 Earthquake (Irpinia, Italy): New Stratigraphical, Structural and Petrological Constrains. Geosciences 2020, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prete, M.; Trisorio Liuzzi, G. Risultati dello studio preliminare della frana di Calitri (AV) mobilitata dal terremoto del 23/11/1980. Geol. Appl. Idrogeol. 1981, 16, 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, E.; Gargiulo, A.; Iaccarino, G.M.; Porfido, S. Distribuzione dei fenomeni franosi riattivati dai terremoti dell’Appennino meridionale. Censimento delle frane del terremoto del 1980. In Proceeding Internal Convention on Prevention of Hydrogeological Hazards; CNR(IRPI): Torino, Italy, 1998; pp. 409–429. [Google Scholar]

- Porfido, S.; Esposito, E.; Michetti, A.M.; Blumetti, A.M.; Vittori, E.; Tranfaglia, G.; Guerrieri, L.; Ferreli, L.; Serva, L. Areal distribution of ground effects induced by strong earthquakes in the Southern Apennines (Italy). Surv. Geophys. 2002, 23, 529–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfido, S.; Esposito, E.; Guerrieri, L.; Vittori, E.; Tranfaglia, G.; Pece, R. Seismically induced ground effects of the 1805, 1930 and 1980 earthquakes in the Southern Apennines. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 2007, 126, 333–346. [Google Scholar]

- Wasowski, J.; Pierri, V.; Pierri, P.; Capolongo, D. Factors controlling seismic susceptibility of the Sele valley slopes: The Case of the 1980 Irpinia Earthquake Re-examined. Surv. Geophys. 2002, 23, 563–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carulli, G.B.; Migliacci, A.; Onofri, R.; Porfido, S. Indagini geologiche ed in prospettiva sismica a S. Michele di Serino. Rend. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1981, 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cotecchia, V.; Salvemini, A. Correlation between seismic events and discharge variations at Caposele and Cassano Irpino springs, with particular reference to the 23 November 1980 earthquake. [Correlazione fra eventi sismici e variazione di portata alle sorgenti di Caposele e Cassano Irpino, con particolare riferimento al sisma del 23 Novembre 1980]. Geol. Appl. Idrogeol. 1981, 16, 167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, P. New empirical relationships between magnitude and distance for liquefaction. Tectonophysics 2000, 324, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, E.; Pece, R.; Porfido, S.; Tranfaglia, G. Hydrological anomalies connected to earthquakes in Southern Apennines, Italy. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. EGS 2001, 1, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osservatorio Permanente sul Doposisma. Edizioni MIdA-2010. p. 114. Available online: http://www.laquilaemotion.it/idee/idee/osservatorio-permanente-sul-doposisma.html (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Siro, L.; Bigi, G.; Testoni, P.; Luongo, G. Indagini di microzonazione sismica. In Intervento Urgente in 39 Comuni della Campania e della Basilicata Colpiti dal Terremoto del 23 Novembre 1980; Pubbl. n. 492; CNR-PFG: Bologna, Italy, 1983; 221p. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, M. Verso una Nuova Qualità dell’abitare: La Riqualificazione dell’edilizia Residenziale Pubblica. Tesi di Dottorato di Ricerca in Ingegneria delle Strutture e del Recupero Edilizio ed Urbano (2007–2010). Available online: http://elea.unisa.it/jspui/handle/10556/156 (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Moscaritolo, G.I. Reconstruction as a Long-Term Process. Memory, Experiences and Cultural Heritage in the Irpinia Post-Earthquake (November 23, 1980). Geosciences 2020, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresca, R.; Nardone, L.; Gizzi, F.T.; Potenza, M.R. Ambient noise HVSR measurements in the Avellino historical centre and surrounding area (southern Italy). Correlation with surface geology and damage caused by the 1980 Irpinia-Basilicata earthquake. Measurement 2018, 130, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artibrune. Dal 2011 Arte Eccetera Eccetera. Available online: https://www.artribune.com/attualita/2011/11/%E2%80%9Cfate-presto%E2%80%9D-stratigrafia-di-un-titolo/ (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Scirè, E.; Siro, L.; Stucchi, M.; Gaiazzi, M. Geo-seismic investigations and urban planning after the Irpinia- 971 Basilicata 1980 earthquake: Part 1, the case of Caposele and Conza della Campania. Geol. Appl. Idrogeol. 1986, 21, 441–450. [Google Scholar]

- Porfido, S.; Spiga, E. Ricostruzione 1980–2020 Ed; Blurb: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; Volume I, ISBN 978-1-71-571504-5. [Google Scholar]

- Porfido, S.; Spiga, E. Ricostruzione 1980–2020 Ed; Blurb: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; Volume II, ISBN 978-1-71-572142-8. [Google Scholar]

- Coletta, T. La Conservazione dei Centri Storici Minori Abbandonati. Il Caso Della Campania. Ph.D. Thesis, Università “Federico II” Napoli, Naples, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, S. I ragazzi dell’Ufficio del Piano la ricostruzione urbanistica in Irpinia. In I frutti di Demetra, Bollettino di Storia Ambientale; Donzelli: Roma, Italy, 2010; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Porfido, S.; Alessio, G.; Gaudiosi, G.; Nappi, R.; Spiga, E. The resilience of some villages 36 years after the Irpinia-Basilicata (Southern Italy) 1980 earthquake. In Workshop on World Landslide Forum; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfido, S.; Spiga, E. Il terremoto del 23 novembre 1980: Ricostruzioni e abbandoni di alcuni paesi nell’Appennino meridionale. The earthquake of November 23rd, 1980: Reconstructions and abandonments of some villages in the southern Apennines. In La Città Altra Storia e Immagine della Diversità Urbana: Luoghi e Paesaggi dei Privilegi e del Benessere, Dell’isolamento, del Disagio, della Multiculturalità; Capano, F., Pascariello, M.I., Visone, M., Eds.; CIRICE: Napoli, Italy, 2018; ISBN 978-88-99930-03-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiga, E.; Porfido, S. Bisaccia Piano di Zona Ed; Blurb: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-71-555296-1. [Google Scholar]

- Locci, M.; Loris Rossi, A. La Concretezza Dell’utopia; Testo & Immagine: Torino, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Scirè, E.; Siro, L.; Stucchi, M.; Gaiazzi, M. Geo-seismic investigations and urban planning after the Irpinia-Basilicata 1980 earthquake: Part 2, the case of S. Angelo dei Lombardi (Italy). Geol. Appl. Idrogeol. 1986, 21, 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, F. The long-term effects of the 1980 earthquake on the villages of southern Italy. Disasters 1984, 894, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D. Housing crisis after natural disasters: The aftermath of the November 1980 southern Italian earthquake. In Geoforum; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984; pp. 489–516. [Google Scholar]

- Guadagno, L. Disastri Naturali e Vulnerabilità Sociale. Un’analisi del Terremoto in Campania. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi del Sannio, Benevento, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wyss, M.; Rosset, P. Near-Real-Time Loss Estimates for Future Italian Earthquakes Based on the M6.9 Irpinia Example. Geosciences 2020, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, M.; Gallo, S. Campania in movimento-Rapporto sulle migrazioni interne in Italia. In Collana “Fuori Collana”; Società editrice il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2020; p. 200. ISBN 978-88-15-28720-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi, T. Avellino. L’Irpinia 40 anni dopo il terremoto, tra cambiamenti e amare continuità. In Rapporto Italiani nel Mondo 2020; Fondazione Migrantes: Roma, Italy, 2020; pp. 95–106. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).