Microbiota in the Early Lives of Sheep: A Short Overview on the Rumen Microbiota

Simple Summary

Abstract

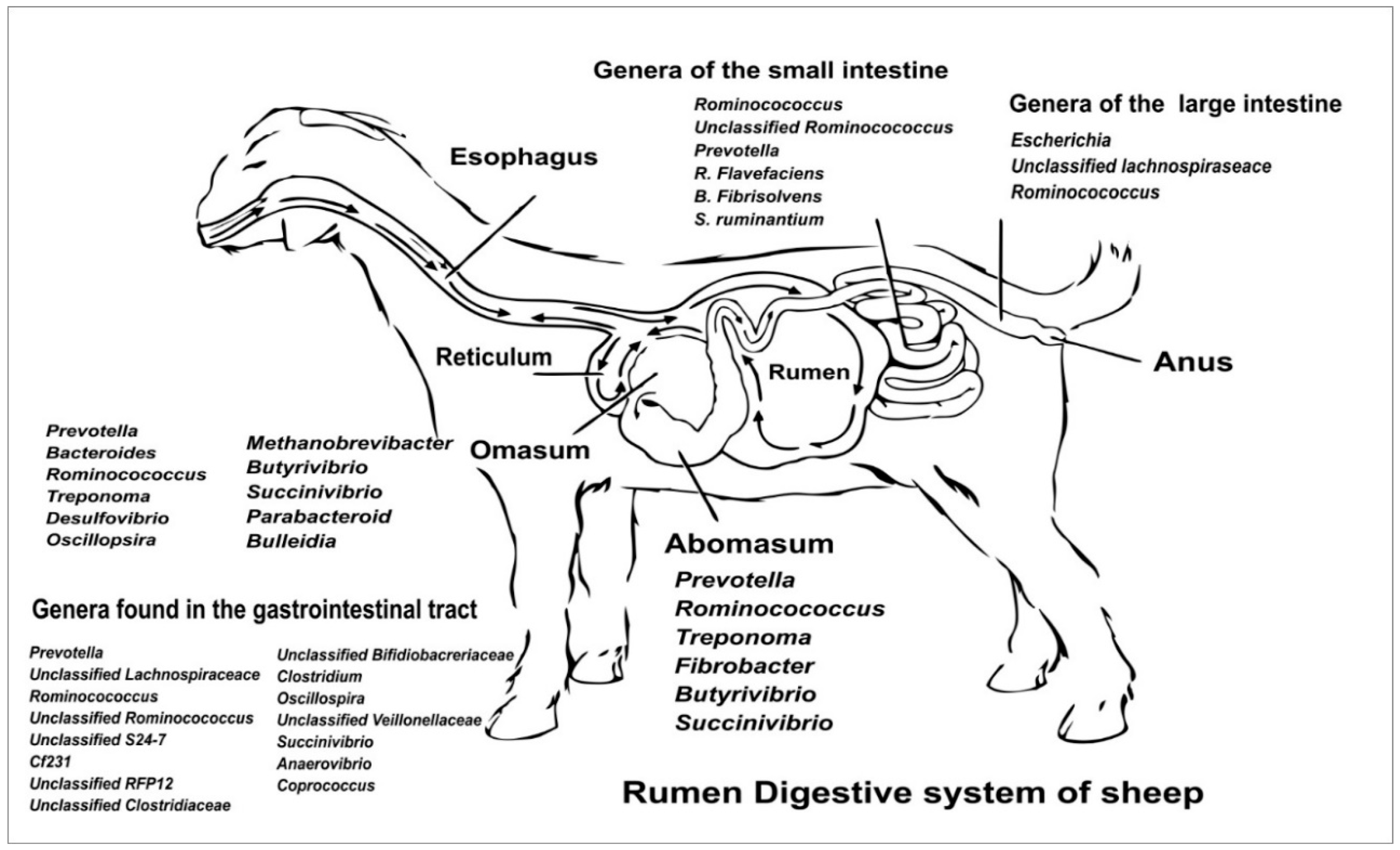

1. Introduction: Composition of Sheep Gut Microbiota

2. Methods

3. Microbiota Colonisation and Development During Early Life

4. Extrinsic Factors That Influence Early Gastrointestinal Tract Colonisation

4.1. Maternal Sources and Diet

4.2. Prebiotics and Probiotics

4.3. Synbiotics

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elghandour, M.M.; Khusro, A.; Adegbeye, M.J.; Tan, Z.; Abu Hafsa, S.; Greiner, R.; Ugbogu, E.; Anele, U.Y.; Salem, A.Z. Dynamic role of single-celled fungi in ruminal microbial ecology and activities. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 128, 950–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, D.; Swanson, K. Nutritional regulation of intestinal starch and protein assimilation in ruminants. Animals 2020, 14, s17–s28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Lei, J.; Yao, Y.; Qu, X.; Chen, J.; Xie, K.; Wang, X.; Yi, Q.; Xiao, B.; Guo, S. Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae meal modulates intestinal morphology and microbiota in Xuefeng black-bone chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 706424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaiquipán, R.; Quiñones, J.; Díaz, R.; Velásquez, C.; Sepúlveda, G.; Velázquez, L.; Paz, E.A.; Tapia, D.; Cancino, D.; Sepúlveda, N. Effect of experimental diets on the microbiome of productive animals. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Lu, N.; Li, S. Nutrient digestibility, microbial fermentation, and response in bacterial composition to methionine dipeptide: An in vitro study. Biology 2022, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraïs, S.; Mizrahi, I. The road not taken: The rumen microbiome, functional groups, and community states. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Luo, S.; Yan, C. Gut microbiota implications for health and welfare in farm animals: A review. Animals 2021, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Chai, J.; Diao, Q.; Huang, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, N. The signature microbiota drive rumen function shifts in goat kids introduced to solid diet regimes. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Ma, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zahoor Khan, M.; Bu, W.; Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. Exploring the effect of gastrointestinal Prevotella on growth performance traits in livestock animals. Animals 2024, 14, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.O.; Dalrymple, B.P.; Smith, W.J.; Mackie, R.I.; McSweeney, C.S. 16S rDNA sequencing of Ruminococcus albus and Ruminococcus flavefaciens: Design of a signature probe and its application in adult sheep. Microbiology 1999, 145, 1797–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Siao, M.; Huang, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Hu, L.; Wei, K.; Zhu, R. The dynamic distribution of small-tail Han sheep microbiota across different intestinal segments. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; He, B.; Qin, Y.; Yang, B.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J. Maternal rumen bacteriota shapes the offspring rumen bacteriota, affecting the development of young ruminants. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0359022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J.; Reese, A.T. Possibilities and limits for using the gut microbiome to improve captive animal health. Anim. Microbiome 2021, 3, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Abecia, L.; Newbold, C.J. Manipulating rumen microbiome and fermentation through interventions during early life: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Li, X.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Tan, Z.; Tang, S.; Zhou, C. Rumen development process in goats as affected by supplemental feeding v. grazing: Age-related anatomic development, functional achievement and microbial colonisation. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Suen, G.; Shao, D.; Li, S.; Diao, Q. Multiomics analysis reveals the presence of a microbiome in the gut of fetal lambs. Gut 2021, 70, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, S.; Hou, L.; Li, K.; Wang, L.; Gao, K.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Z. Supplemental choline modulates growth performance and gut inflammation by altering the gut microbiota and lipid metabolism in weaned piglets. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmuthuge, N.; Liang, G.; Guan, L.L. Regulation of rumen development in neonatal ruminants through microbial metagenomes and host transcriptomes. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Ji, S.; Duan, C.; Tian, P.; Ju, S.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Age-related changes in the ruminal microbiota and their relationship with rumen fermentation in lambs. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 679135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunière, L.; Ruiz, P.; Lebbaoui, Y.; Guillot, L.; Bernard, M.; Forano, E.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F. Effects of rearing mode on gastro-intestinal microbiota and development, immunocompetence, sanitary status and growth performance of lambs from birth to two months of age. Anim. Microbiome 2023, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, M.; Enjalbert, F.; Combes, S.; Cauquil, L.; Bouchez, O.; Monteils, V. Establishment of ruminal bacterial community in dairy calves from birth to weaning is sequential. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Li, B.; Guo, M.; Liu, G.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, E. Maturation of the goat rumen microbiota involves three stages of microbial colonization. Animals 2019, 9, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, G. Dynamics and stabilization of the rumen microbiome in yearling Tibetan sheep. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Choi, S.; Nogoy, K.; Liang, S. The development of the gastrointestinal tract microbiota and intervention in neonatal ruminants. Animals 2021, 15, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, Q.; Kong, F.; Yang, Y.; Wu, D.; Mishra, S.; Li, Y. Exploring the goat rumen microbiome from seven days to two years. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Ji, S.-K.; Duan, C.-H.; Tian, P.-Z.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Liu, Y.-Q. Dynamic change of fungal community in the gastrointestinal tract of growing lambs. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 3314–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewińska, P.; Czyż, K.; Nowakowski, P.; Wyrostek, A. The microbiome of the digestive system of ruminants—A review. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2020, 21, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y. Characterization and comparison of microbiota in the gastrointestinal tracts of the goat (Capra hircus) during preweaning development. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewińska, P.; Górniak, W.; Wojnarowski, K. Impact of selected environmental factors on microbiome of the digestive tract of ruminants. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Zingaretti, L.; Popova, M.; Estellé, J.; Bernard, A.; Pons, N.; Bellot, P.; Mach, N.; Rau, A.; Roume, H. Identification of rumen microbial biomarkers linked to methane emission in Holstein dairy cows. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2020, 137, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Beak, S.-H.; Kim, S.Y.; Jeong, I.H.; Piao, M.Y.; Kang, H.J.; Fassah, D.M.; Na, S.W.; Yoo, S.P.; Baik, M. Genetic, management, and nutritional factors affecting intramuscular fat deposition in beef cattle—A review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, S.H.; Conti, E.; Ricci, L.; Walker, A.W. Links between diet, intestinal anaerobes, microbial metabolites and health. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; Jiang, L.; Mao, S. Effect of high-concentrate diets on microbial composition, function, and the VFAs formation process in the rumen of dairy cows. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 269, 114619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houtert, M. The production and metabolism of volatile fatty acids by ruminants fed roughages: A review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1993, 43, 189–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Liang, Y.; Ji, K.; Feng, M.; Du, X.; Jiao, D.; Wu, X.; Zhong, C.; Cong, H.; Yang, G. Enhanced propionate and butyrate metabolism in cecal microbiota contributes to cold-stress adaptation in sheep. Microbiome 2025, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, L.; Loh, K.-C. Review and perspectives of enhanced volatile fatty acids production from acidogenic fermentation of lignocellulosic biomass wastes. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. The effects of different concentrate-to-forage ratio diets on rumen bacterial microbiota and the structures of Holstein cows during the feeding cycle. Animals 2020, 10, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, C.; Mao, H. Nitrogen utilization and ruminal microbiota of Hu lambs in response to varying dietary metabolizable protein levels. Animals 2025, 15, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Du, M.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Lee, Y.; Zhang, G. Diet type impacts production performance of fattening lambs by manipulating the ruminal microbiota and metabolome. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 824001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Ameilbonne, A.; Bichat, A.; Mosoni, P.; Ossa, F.; Forano, E. Live yeasts enhance fibre degradation in the cow rumen through an increase in plant substrate colonization by fibrolytic bacteria and fungi. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku-Vera, J.C.; Jiménez-Ocampo, R.; Valencia-Salazar, S.S.; Montoya-Flores, M.D.; Molina-Botero, I.C.; Arango, J.; Gómez-Bravo, C.A.; Aguilar-Pérez, C.F.; Solorio-Sánchez, F.J. Role of secondary plant metabolites on enteric methane mitigation in ruminants. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaio, D.; DeMaere, M.Z.; Anantanawat, K.; Chapman, T.A.; Djordjevic, S.P.; Darling, A.E. Post-weaning shifts in microbiome composition and metabolism revealed by over 25,000 pig gut metagenome-assembled genomes. Microb. Genom. 2021, 7, 000501. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Chai, J.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, N.; Cui, K.; Bi, Y.; Ma, T.; Tu, Y.; Diao, Q. The temporal dynamics of rumen microbiota in early weaned lambs. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowiak, P.; Śliżewska, K. The role of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in animal nutrition. Gut Pathog. 2018, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.; Fouhse, J.M.; Tiwari, U.P.; Li, L.; Willing, B.P. Dietary fiber and intestinal health of monogastric animals. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.R.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: Introducing the concept of prebiotics. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Campaniello, D.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. An update on prebiotics and on their health effects. Foods 2024, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijada, N.M.; Bodas, R.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Rodríguez-Lázaro, D.; Hernández, M. Dietary supplementation with sugar beet fructooligosaccharides and garlic residues promotes growth of beneficial bacteria and increases weight gain in neonatal lambs. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chashnidel, Y.; Bahari, M.; Yansari, A.T.; Kazemifard, M. The effects of dietary supplementation of prebiotic and peptide on growth performance and blood parameters in suckling Zell lambs. Small Rum. Res. 2020, 188, 106121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Trwab, A.; Youssef, I.; Bakr, H.; Fthenakis, G.; Giadinis, N. Role of probiotics in nutrition and health of small ruminants. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2016, 19, 893–906. [Google Scholar]

- Antunović, Z.; Šperanda, M.; Amidžić, D.; Šerić, V.; Stainer, Z.; Domačinović, M.; Boli, F. Probiotic application in lambs nutrition. Krmiva Časopis O Hranidbi Zivotinj. Proizv. I Tehnol. Krme 2006, 48, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, N.C.; Cazac, D.; Rude, B.; Jackson-O’Brien, D.; Parveen, S. Use of a commercial probiotic supplement in meat goats. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B.; Wilson, D.B. Why are ruminal cellulolytic bacteria unable to digest cellulose at low pH? J. Dairy Sci. 1996, 79, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, L.; Botha, P.; Kistner, A. Effect of yeast culture supplement on production, rumen fermentation, and duodenal nitrogen flow in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1992, 75, 3056–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Walker, N.; Bach, A. Effects of active dry yeasts on the rumen microbial ecosystem: Past, present and future. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 145, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.K.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, M.H.; Upadhaya, S.D.; Kam, D.K.; Ha, J.K. Direct-fed microbials for ruminant animals. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 23, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Ran, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, P.; Chen, J.; Loor, J.J. Inoculation of newborn lambs with ruminal solids derived from adult goats reprograms the development of gut microbiota and serum metabolome and favors growth performance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Liu, C.; Chen, X.; Yang, Z.; Hu, G.; Zhang, M.; Sun, L.; Su, L.; Zhao, L.; Jin, Y. Supplemental Clostridium butyricum modulates skeletal muscle development and meat quality by shaping the gut microbiota of lambs. Meat Sci. 2023, 204, 109235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devyatkin, V.; Mishurov, A.; Kolodina, E. Probiotic effect of Bacillus subtilis B-2998D, B-3057D, and Bacillus licheniformis B-2999D complex on sheep and lambs. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2021, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Villot, C.; Renaud, D.; Skidmore, A.; Chevaux, E.; Steele, M.; Guan, L.L. Linking perturbations to temporal changes in diversity, stability, and compositions of neonatal calf gut microbiota: Prediction of diarrhea. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2223–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyoatmojo, D.; Maharani, Y.; Ansori, D.; Hardani, S.; Trinugraha, A.; Handayani, T.; Sasongko, W.; Wahyono, T. Effects of harvesting time on tannin biological activity in sambiloto (Andrographis paniculata) leaves and in vitro diet digestibility supplemented with sambiloto leaves. J. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 9, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mehanna, S.; Abdelsalam, M.; Hashem, N.; El-Azrak, K.; Mansour, M.; Zeitoun, M. Relevance of probiotic, prebiotic and synbiotic supplementations on hemato-biochemical parameters, metabolic hormones, biometric measurements and carcass characteristics of sub-tropical Noemi lambs. Int. J. Anim. Res. 2017, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Svitáková, A.; Schmidová, J.; Pešek, P.; Novotná, A. Recent developments in cattle, pig, sheep and horse breeding—A review. Acta Vet. Brno 2014, 83, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Luo, Y.; Su, R.; Yao, D.; Hou, Y.; Liu, C.; Du, R.; Jin, Y. Impact of feeding regimens on the composition of gut microbiota and metabolite profiles of plasma and feces from Mongolian sheep. J. Microbiol. 2020, 58, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouhse, J.M.; Smiegielski, L.; Tuplin, M.; Guan, L.L.; Willing, B.P. Host immune selection of rumen bacteria through salivary secretory IgA. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Song, Y.; He, Z.; Haines, D.; Guan, L.; Steele, M. Effect of delaying colostrum feeding on passive transfer and intestinal bacterial colonization in neonatal male Holstein calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3099–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, R.; Małaczewska, J.; Tobolski, D.; Miciński, J.; Kaczorek-Łukowska, E.; Zwierzchowski, G. The effect of orally administered multi-strain probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) on the phagocytic activity and oxidative metabolism of peripheral blood granulocytes and monocytes in lambs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Ji, W.; Yun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, C. Influence of probiotic supplementation on the growth performance, plasma variables, and ruminal bacterial community of growth-retarded lamb. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1216534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daszkiewicz, T.; Miciński, J.; Wójcik, R.; Tobolski, D.; Zwierzchowski, G.; Kobzhassarov, T.; Ząbek, K.; Charkiewicz, K. The effect of probiotic supplementation in Kamieniec lambs on meat quality. Small Rumin. Res. 2025, 244, 107444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhidhik Arifin, H.; Rianto, E.; Purbowati, E.; Muktiani, A. The potential of synbiotics supplementation using gembili inulin as a prebiotic in improving fermentability and productivity of lambs fed diet of different fibre content. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2025, 13, 1502–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Xu, X.; Luo, D.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S.; He, R.; An, T.; Sun, Q. Effect of dietary supplementation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum N-1 and its synergies with oligomeric isomaltose on the growth performance and meat quality in Hu sheep. Foods 2023, 12, 1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atmaja, B.A.; Agusetyaningsih, I.; Ali, M.I.; Adikara, Y.a.R.; Hidayatulloh, R.; Herviyanto, D.; Lestari, W.M.; Hutabarat, A.L.R.; Safitri, A.R.; Ali, A.M. The potential of Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a biological control agent against gastrointestinal nematodes in sheep. J. Anim. Health Prod. 2025, 13, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwenya, B.; Santoso, B.; Sar, C.; Gamo, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Arai, I.; Takahashi, J. Effects of including β1–4 galacto-oligosaccharides, lactic acid bacteria or yeast culture on methanogenesis as well as energy and nitrogen metabolism in sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2004, 115, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeid, H.M.; Kholif, A.M.; Farghly, M.S.; Khattab, M.S.A. Effect of propionibacteria supplementation to sheep diets on rumen fermentation, nutrients, digestibility and blood metabolites. Sci. Int. 2013, 1, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jia, W.; Zhang, B.; Sun, S.; Dou, X.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Ren, G.; et al. Effects of diet xylooligosaccharide supplementation on growth performance, carcass characteristics, and meat quality of Hu lambs. Foods 2025, 11, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, O.; Cervantes, A.; Barreras, A.; Monge-Navarro, F.; González-Vizcarra, V.M.; Estrada-Angulo, A.; Urías-Estrada, J.D.; Corona, L.; Zinn, R.A.; Martínez-Alvarez, L.G.; et al. Effects of single or combined supplementation of probiotics and prebiotics on ruminal fermentation, ruminal bacteria and total tract digestion in lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2021, 2024, 106538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (Days) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 7 | 14 | 28 | 42 | |

| Bacteria | |||||

| Proteobacteria | >50% | 10–30% | 10–30% | 10–30% | 10–30% |

| Bacteroidetes | 10–30% | >50% | >50% | >50% | >50% |

| Firmicutes | 10–30% | 10–30% | 10–30% | 10–30% | 10–30% |

| Actinobacteria | 2–10% | 2–10% | 2–10% | 2–10% | 2–10% |

| Fusobacteria | 2–10% | 2–10% | <2% | <2% | <2% |

| Spirochaetes | <2% | <2% | <2% | <2% | <2% |

| Fibrobacteres | <2% | <2% | <2% | <2% | <2% |

| Tenericutes | - | <2% | <2% | - | - |

| Elusimicrobia | - | - | <2% | <2% | 2–10% |

| Lentisphaerae | - | - | <2% | <2% | <2% |

| Archaea | |||||

| Euryarchaeota | <2% | <2% | 2–10% | ||

| Fungi | |||||

| Aspergillus | 2–10% | 10–30% | |||

| Protozoa | 10–30% | 10–30% | 2–10% | - | - |

| Endomorphs | 10–30% | 10–30% | 2–10% | - | - |

| Early Colonisation and Pre-Weaning | |

| Sources | Dam’s vagina, udder skin, and colostrum/milk “seeds” microbiota |

| Breastfeeding | Contributes to immune development and to the establishment of an early microbial ecosystem |

| Early solid feed introduction | Could limit growth loss during transition phase, and affects microbial assembly |

| Milk vs. replace | Could determine a shift from Prevotella to Bacteroides |

| Post-Weaning | |

| High concentrate/diets rich in starch | Enhancement of amylolytic and saccharolytic taxa Increase in VFA, changes in the ratio acetate vs. propionate, with an increase energy efficiency |

| Excessive concentrate | Reduction in pH in the rumen, favouring lactate producers and decreasing fibrolytic taxa |

| Diets rich in fibre | Positive effect on fibrolytic bacteria, pH homeostasis, and microbial diversity |

| Physical form of diet | Pelleted rations positively modulate fibrolytic bacteria, but could impact on alpha diversity |

| Additives | Yeasts stabilise pH and have a positive impact on fibrolytic bacteria and on lactate producers Microalgae improve feed efficiency Plant metabolites can impact on methanogenic bacteria and protozoa |

| Probiotic | Prebiotic | Synbiotic |

|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and their combinations [68,69,70] | Inulin [71] | Lactobacilli + inulin [72] |

| Saccharomyces [73] | GOSs [74] | Lactobacilli + FOS [66] |

| FOSs [49] | S. cerevisiae + MOS + BG [73] | |

| Propionibacteria [75] | XOS [76] | |

| Rumen extracts [58] | MOS [77] | |

| Clostridium butyricum [59] | BG [77] | |

| Bacillus subtilis [60] | MOS + BG [50] | |

| Bacillus licheniformis [60] |

| Prebiotics | |

| Biodiversity and richness of microbiota | + |

| Faecal levels of Veillonella, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Enterococcus | + |

| Probiotics | |

| Biodiversity and richness | + |

| Petrimonas and Prevotella in the rumen | + |

| Lachnospirillum, Alloprevotella and Prevotella in the faeces | + |

| Bacteroidetes, Spirochaetota, and Fibrobacterota | + |

| Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium | + |

| Fusobacteria | − |

| Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus | − |

| Synbiotics | |

| Biodiversity | + |

| Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium | + |

| Enterobacteriaceae | − |

| Clostridium | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bevilacqua, A.; Khan, S.; Caroprese, M.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Albenzio, M. Microbiota in the Early Lives of Sheep: A Short Overview on the Rumen Microbiota. Animals 2026, 16, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010080

Bevilacqua A, Khan S, Caroprese M, Speranza B, Racioppo A, Albenzio M. Microbiota in the Early Lives of Sheep: A Short Overview on the Rumen Microbiota. Animals. 2026; 16(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleBevilacqua, Antonio, Suleman Khan, Mariangela Caroprese, Barbara Speranza, Angela Racioppo, and Marzia Albenzio. 2026. "Microbiota in the Early Lives of Sheep: A Short Overview on the Rumen Microbiota" Animals 16, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010080

APA StyleBevilacqua, A., Khan, S., Caroprese, M., Speranza, B., Racioppo, A., & Albenzio, M. (2026). Microbiota in the Early Lives of Sheep: A Short Overview on the Rumen Microbiota. Animals, 16(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010080