Workplace Strategies to Reduce Burnout in Veterinary Nurses and Technicians: A Delphi Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

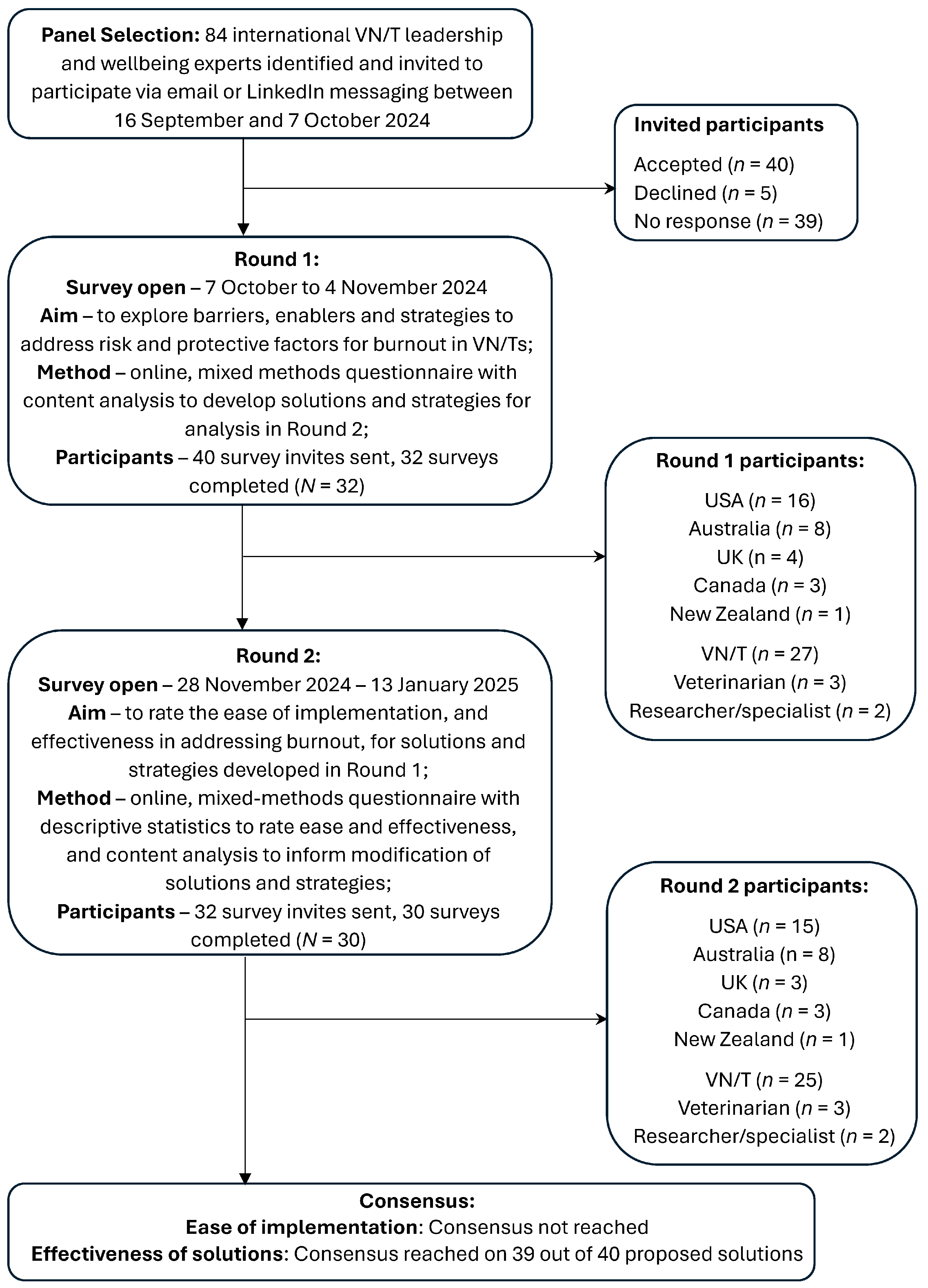

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Measures

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Round 1

3.3. Round 2

4. Discussion

4.1. Industry-Wide Barriers

4.2. Clinic Specific Barriers

4.3. Solutions

4.3.1. Risk Factors

4.3.2. Protective Factors

4.4. Implementation of Solutions

4.5. Limitations and Further Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAHA | American Animal Hospital Association |

| DVM | Doctor of Veterinary Medicine |

| ILO | International Labour Organisation |

| OHS | Occupational Health and Safety |

| SOPs | Standard Operating Procedures |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| VN/T | Veterinary nurse and technician |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

References

- Moore, I.C.; Coe, J.B.; Adams, C.L.; Conlon, P.D.; Sargeant, J.M. The role of veterinary team effectiveness in job satisfaction and burnout in companion animal veterinary clinics. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2014, 245, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brscic, M.; Contiero, B.; Schianchi, A.; Marogna, C. Challenging suicide, burnout, and depression among veterinary practitioners and students: Text mining and topics modelling analysis of the scientific literature. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffey, M.A.; Griffon, D.J.; Risselada, M.; Scharf, V.F.; Buote, N.J.; Zamprogno, H.; Winter, A.L. Veterinarian burnout demographics and organizational impacts: A narrative review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1184526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, A.J.; Rohlf, V.I.; Moser, A.Y.; Bennett, P.C. Organizational Factors Affecting Burnout in Veterinary Nurses: A Systematic Review. Anthrozoös 2024, 37, 651–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, J.O.; Schimmack, U.; Strand, E.B.; Reinhard, A.; Hahn, J.; Andrews, J.; Probyn-Smith, K.; Jones, R. Merck Animal Health Veterinary Team study reveals factors associated with well-being, burnout, and mental health among nonveterinarian practice team members. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2024, 262, 1330–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Hall, L.H.; Berzins, K.; Baker, J.; Melling, K.; Thompson, C. Mental healthcare staff well-being and burnout: A narrative review of trends, causes, implications, and recommendations for future interventions. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.A.; Gee, P.M.; Butler, R.J. Impact of nurse burnout on organizational and position turnover. Nurs. Outlook 2021, 69, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagioni, D.A.J.; Melanda, F.N.; Mesas, A.E.; González, A.D.; Gabani, F.L.; Andrade, S.M.d. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. International Classification of Diseases; 11th Revision; ICD-11; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Mental Health at Work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/topics/safety-and-health-work/mental-health-work (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- WHO. WHO Guidelines on Mental Health at Work; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-005305-2. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Psychosocial Risks and Stress at Work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/psychosocial-risks-and-stress-work (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Chapman, A.J.; Rohlf, V.I.; Moser, A.Y.; Bennett, P.C. Understanding Veterinary Technician and Nurse Burnout. Part 2: Addressing Veterinary Technician Burnout Requires Tailored Organizational Wellbeing Initiatives. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2025. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, A.F. Workplace incivility: A literature review. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2020, 13, 513–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.; Polly, Y.; Louise, C.B.; O’Donoghue, K. Reducing the “cost of caring” in animal-care professionals: Social work contribution in a pilot education program to address burnout and compassion fatigue. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2021, 31, 828–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.J.; Rohlf, V.I.; Bennett, P.C. Understanding Veterinary Technician and Nurse Burnout. Part 1: Burnout Profiles Reveal High Workload and Lack of Support are Among Major Workplace Contributors to Burnout. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2025. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Black, A.F.; Winefield, H.R.; Chur-Hansen, A. Occupational stress in veterinary nurses: Roles of the work environment and own companion animal. Anthrozoös 2011, 24, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.M.; Maples, E.H. Occupational stress in veterinary support staff. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2014, 41, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.; Kontak, J.; Jeffers, E.; Lawson, B.; MacKenzie, A.; Burge, F.; Boulos, L.; Lackie, K.; Marshall, E.G.; Mireault, A.; et al. Barriers and enablers to implementing interprofessional primary care teams: A narrative review of the literature using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, C.; Hansez, I. Temporal Stages of Burnout: How to Design Prevention? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2024, 21, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, G.M.; LaLonde-Paul, D.F.; Perret, J.L.; Steele, A.; McConkey, M.; Lane, W.G.; Kopp, R.J.; Stone, H.K.; Miller, M.; Jones-Bitton, A. Investigation of burnout syndrome and job-related risk factors in veterinary technicians in specialty teaching hospitals: A multicenter cross-sectional study. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2020, 30, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, L.R.; Wallace, J.E.; Schoenfeld-Tacher, R.; Hellyer, P.W.; Richards, M. Veterinary technicians and occupational burnout. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holowaychuk, M.K.; Lamb, K.E. Burnout symptoms and workplace satisfaction among veterinary emergency care providers. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2023, 33, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, M.; Correia, I. Empathy and Burnout in Veterinarians and Veterinary Nurses: Identifying Burnout Protectors. Anthrozoös 2023, 36, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, S.; Reese, C.; Wendler, M.C. Methodology Update: Delphi Studies. Nurs. Res. 2018, 67, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reavley, N.J.; Ross, A.; Martin, A.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Jorm, A.F. Development of guidelines for workplace prevention of mental health problems: A Delphi consensus study with Australian professionals and employees. Ment. Health Prev. 2014, 2, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-García, G.; Ayala, J.C. Insufficiently studied factors related to burnout in nursing: Results from an e-Delphi study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalkey, N.; Helmer, O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manag. Sci. 1963, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederberger, M.; Schifano, J.; Deckert, S.; Hirt, J.; Homberg, A.; Köberich, S.; Kuhn, R.; Rommel, A.; Sonnberger, M.; DEWISS Network. Delphi studies in social and health sciences—Recommendations for an interdisciplinary standardized reporting (DELPHISTAR). Results of a Delphi study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.B.H.; Pilkington, P.D.; Ryan, S.M.; Kelly, C.M.; Jorm, A.F. Parenting strategies for reducing the risk of adolescent depression and anxiety disorders: A Delphi consensus study. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 156, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QuestionPro. QuestionPro API V2; QuestionPro: Austin, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lumivero. NVivo (Version 14); Lumivero: Denver, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, F. Opportunities for New Zealand veterinary practice in the utilisation of allied veterinary professional and paraprofessional staff. Scope Health Wellbeing 2022, 7, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, A.R.; Celt, V.P.; Pilewki, L.E.; Hendricks, M.K. The newly credentialed veterinary technician: Perceptions, realities, and career challenges. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1437525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prendergast, H.; Mages, A.; Rauscher, J.; Roth, C.; Thompson, M.; Thompson, S.T.; Yagi, K. 2023 AAHA Technician Utilization Guidelines; AAHA: Lakewood, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Skakon, J.; Karina, N.; Vilhelm, B.; Guzman, J. Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work. Stress. 2010, 24, 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtright, S.; Colbert, A.; Choi, D. Fired Up or Burned Out? How Developmental Challenge Differentially Impacts Leader Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.; Crown, S.N.; Ivany, M. Organisational change and employee burnout: The moderating effects of support and job control. Saf. Sci. 2017, 100, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.L.; Crabtree, B.F.; Nutting, P.A.; Stange, K.C.; Jaén, C.R. Primary Care Practice Development: A Relationship-Centered Approach. Ann. Fam. Med. 2010, 8, S68–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moore, I.C.; Coe, J.B.; Adams, C.L.; Conlon, P.D.; Sargeant, J.M. Exploring the Impact of Toxic Attitudes and a Toxic Environment on the Veterinary Healthcare Team. Front. Vet. Sci. 2015, 2, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosadeghrad, A.M.; Ansarian, M. Why do organisational change programmes fail? Int. J. Strateg. Change Manag. 2014, 5, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgalis, J.; Samaratunge, R.; Kimberley, N.; Lu, Y. Change process characteristics and resistance to organisational change: The role of employee perceptions of justice. Aust. J. Manag. 2015, 40, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Six areas of worklife: A model of the organizational context of burnout. J. Health Hum. Serv. Adm. 1999, 21, 472–489. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.; Nguyen, H.; Groth, M.; Wang, K.; Ng, J.L. Time to change: A review of organisational culture change in health care organisations. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2016, 3, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Generating Short Term Wins. In Leading Change; Harvard Business Review Press: La Vergne, TN, USA, 2012; pp. 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fults, M.K.; Yagi, K.; Kramer, J.; Maras, M. Development of Advanced Veterinary Nursing Degrees: Rising Interest Levels for Careers as Advanced Practice Registered Veterinary Nurses. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2021, 48, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, A.; Taylor, E. Veterinary nursing in the United Kingdom: Identifying the factors that influence retention within the profession. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 927499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, M.; Cannedy, S.; Oishi, K.; Canelo, I.; Hamilton, A.B.; Olmos-Ochoa, T.T. Using Stay Interviews as a Quality Improvement Tool for Healthcare Workforce Retention. Qual. Manag. Health Care 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.; Whiteman, K.; DiCuccio, M.; Swanson-Biearman, B.; Stephens, K. Why They Stay and Why They Leave: Stay Interviews with Registered Nurses to Hear What Matters the Most. J. Nurs. Adm. 2023, 53, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Successful Change and the Force That Drives it. In Leading Change; Harvard Business Review Press: La Vergne, TN, USA, 2012; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnes, B. Introduction: Why Does Change Fail, and What Can We Do About It? J. Change Manag. 2011, 11, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idogawa, J.; Bizarrias, F.S.; Câmara, R. Critical success factors for change management in business process management. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2023, 29, 2009–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolay, C.R.; Williams, S.P.; Brkic, M.; Purkayastha, S.; Chaturvedi, S.; Phillips, N.; Darzi, A. Measuring the organisational health of acute sector healthcare organisations: Development and validation of the Healthcare-OH survey. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2021, 14, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.; Hamilton, S.; McSherry, R.; McIntosh, R. Measuring and Assessing Healthcare Organisational Culture in the England’s National Health Service: A Snapshot of Current Tools and Tool Use. Healthcare 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, N.; Mahmood, A.; Ibtasam, M.; Murtaza, S.A.; Iqbal, N.; Molnár, E. The Psychology of Resistance to Change: The Antidotal Effect of Organizational Justice, Support and Leader-Member Exchange. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 678952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, R.E.; Knesl, O. How can the veterinary profession tackle social media misinformation? J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2025, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holey, E.A.; Feeley, J.L.; Dixon, J.; Whittaker, V.J. An exploration of the use of simple statistics to measure consensus and stability in Delphi studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasa, P.; Jain, R.; Juneja, D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: How to decide its appropriateness. World J. Methodol. 2021, 11, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Risk Factor | Barriers to Addressing the Risk Factor Derived from Content Analysis Themes | Enablers to Addressing the Risk Factor Derived from Content Analysis Themes | Perceived Ease of Management Rating (Mean/5.00 (SD)) | Consensus Rating (Participant Agreement %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The workload is too high |

|

| 2.66/5.00 (±0.79) | Consensus: Difficult/neither difficult nor easy (82.93%) |

| 2. There is a lack of opportunities to utilise skills and knowledge for which veterinary nurses/technicians are trained and qualified |

|

| 3.00/5.00 (±1.14) | Consensus not reached |

| 3. A negative team culture exists (for example: bullying, gossiping, criticism, or general incivility) |

|

| 2.52/5.00 (±0.96) | Consensus not reached |

| 4. There is a lack of, or unclear communication from both management and within the team |

|

| 3.23/5.00 (±1.07) | Consensus not reached |

| 5. There is poor management/leadership of the team (for example: micromanagement, favouritism, lack of support, or lack of action on team conflict) |

|

| 2.38/5.00 (±1.01) | Consensus not reached |

| 6. There is an expectation of working overtime, not having a break, and a general lack of flexibility in rostering |

|

| 2.86/5.00 (±0.92) | Consensus not reached |

| 7. Remuneration is poor |

|

| 2.48/5.00 (±0.99) | Consensus not reached |

| 8. There is a lack of opportunity for progression or development |

|

| 2.79/5.00 (±0.86) | Consensus: Difficult/neither difficult nor easy (80.65%) |

| 9. Having to deal with rude or abusive clients |

|

| 2.86/5.00 (±1.13) | Consensus: Difficult/Neither difficult nor easy (97.74%) |

| 10. There is a lack of appreciation, feeling valued, or being heard, by management |

|

| 2.86/5.00 (±1.27) | Consensus not reached |

| Protective Factor | Barriers to Leveraging the Protective Factor Derived from Content Analysis Themes | Enablers to Leveraging the Protective Factor Derived from Content Analysis Themes | Perceived Ease of Leverage Rating (Mean/5.00 (SD)) | Consensus Rating (Participant Agreement %) |

| 1. Having some control over the schedule or expected tasks |

|

| 3.09/5.00 (±0.89) | Consensus not reached |

| 2. Knowledge of having a positive impact on a patient or client |

|

| 3.74/5.00 (±1.03) | Consensus not reached |

| 3. Being trusted with, and involved in, decisions around patient care |

|

| 3.13/5.00 (±0.98) | Consensus not reached |

| Risk Factor | Solution | Perceived Ease of Implementation Rating (Mean/5.00 (SD)) | Consensus Rating (Participant Agreement %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The workload is too high | Hire more staff | 2.23/5.00 (±0.57) | Consensus: Difficult/neither easy nor difficult (96.33%) |

| Improve staff retention | 3.20/5.00 (±1.03) | Consensus not reached | |

| Implement workload management systems to enhance efficiency and communications around workload issues | 3.60/5.00 (±1.07) | Consensus not reached | |

| Preventative healthcare focus to reduce the number of cases seen | 2.62/5.00 (±1.06) | Consensus not reached | |

| 2. There is a lack of opportunities to utilise skills and knowledge for which veterinary nurses/technicians are trained and qualified | Provide role clarity on skill level and task expectations of VN/Ts and veterinarians | 3.80/5.00 (±1.19) | Consensus not reached |

| Support veterinarians to delegate tasks to VN/Ts | 3.30/5.00 (±1.06) | Consensus not reached | |

| Create opportunities for skill utilisation by reducing non-clinical workload and increasing clinical work opportunities | 3.30/5.00 (±1.02) | Consensus not reached | |

| Implement systems to support delegation | 3.33/5.00 (±1.12) | Consensus not reached | |

| 3. A negative team culture exists (for example: bullying, gossiping, criticism, or general incivility) | Zero-tolerance to incivility at all levels of the workplace | 2.67/5.00 (±1.24) | Consensus not reached |

| Promote culture change | 3.17/5.00 (±1.12) | Consensus not reached | |

| Set clear expectations on expected behaviour | 3.63/5.00 (±1.22) | Consensus not reached | |

| Provide staff and leadership training and support | 3.97/5.00 (±1.0) | Consensus: Easy/Very easy (76.66%) | |

| 4. There is a lack of, or unclear, communication from both management and within the team | Increase communication opportunities | 3.86/5.00 (±1.01) | Consensus not reached |

| Promote and reward good communication | 3.57/5.00 (±1.03) | Consensus not reached | |

| Develop clear communication protocols and reporting lines | 3.89/5.00 (±0.96) | Consensus not reached | |

| Utilise different communication methods | 3.64/5.00 (±1.10) | Consensus not reached | |

| 5. There is poor management/leadership of the team (for example: micromanagement, favouritism, lack of support, or lack of action on team conflict) | Improve leadership recruitment and training processes | 2.67/5.00 (±1.06) | Consensus not reached |

| Implement systems to support leaders | 3.00/5.00 (±1.02) | Consensus not reached | |

| Improve workplace communication | 3.50/5.00 (±1.01) | Consensus not reached | |

| Initiate leadership reviews and accountability | 3.53/5.00 (±1.04) | Consensus not reached | |

| 6. There is an expectation of working overtime, not having a break, and a general lack of flexibility in rostering | Review and adjust staffing to meet clinic needs | 2.47/5.00 (±1.04) | Consensus not reached |

| Implement clear break and overtime policies | 3.23/5.00 (±1.10) | Consensus not reached | |

| Provide leadership and team training | 3.33/5.00 (±1.15) | Consensus not reached | |

| Review and implement workflow systems to streamline tasks and develop contingency plans | 3.00/5.00 (±0.95) | Consensus not reached | |

| 7. Remuneration is poor | Offer non-monetary remuneration | 2.63/5.00 (±1.19) | Consensus not reached |

| Explore opportunities to increase revenue | 3.23/5.00 (±1.14) | Consensus not reached | |

| Implement salary banding and progression pathways | 3.60/5.00 (±1.28) | Consensus not reached | |

| Implement work processes to reduce costs | 3.17/5.00 (±1.18) | Consensus not reached | |

| 8. There is a lack of opportunity for progression or development | Develop clear progression pathways for VN/Ts | 3.33/5.00 (±1.12) | Consensus not reached |

| Explore professional growth opportunities | 3.43/5.00 (±1.17) | Consensus not reached | |

| Provide internal VN/T training and support | 3.30/5.00 (±1.12) | Consensus not reached | |

| Promote external VN/T training and support | 3.47/5.00 (±1.17) | Consensus not reached | |

| 9. Having to deal with rude or abusive clients | Provide clear expectations on client conflict management and empower the team | 3.73/5.00 (±1.05) | Consensus not reached |

| Create workplace support systems for VN/Ts faced with client abuse | 3.40/5.00 (±1.00) | Consensus not reached | |

| Prepare and train the team for conflict situations | 3.53/5.00 (±0.97) | Consensus not reached | |

| Communicate clear behavioural expectations to clients | 3.93/5.00 (±0.83) | Consensus: Easy/very easy (76.66%) | |

| 10. There is a lack of appreciation, feeling valued, or being heard, by management | Implement VN/T recognition systems | 3.70/5.00 (±0.99) | Consensus not reached |

| Increase communication channels between management and VN/Ts | 3.67/5.00 (±0.96) | Consensus not reached | |

| Provide support and training for leaders | 3.79/5.00 (±1.05) | Consensus not reached | |

| Identify what appreciation looks like for individuals | 3.90/5.00 (±0.92) | Consensus not reached | |

| Protective Factor | Promotion Strategy | Perceived Ease of Implementation Rating (Mean/5.00 (SD)) | Consensus Rating (Participant Agreement %) |

| 1. Having some control over the schedule or expected tasks | Adopt a collaborative team scheduling approach | 3.37/5.00 (±1.10) | Consensus not reached |

| Upskill and cross-train VN/Ts | 3.07/5.00 (±1.08) | Consensus not reached | |

| Develop clear expectations for VN/T tasks and roles | 3.93/5.00 (±0.83) | Consensus: Easy/very easy (76.66%) | |

| Implement work systems to enhance clarity and communications around scheduling | 3.53/5.00 (±1.04) | Consensus not reached | |

| 2. Knowledge of having a positive impact on a patient or client | Implement peer feedback systems | 4.16/5.00 (±0.80) | Consensus: Easy/Very easy (84%) |

| Encourage clear and open communication within the team | 3.37/5.00 (±1.25) | Consensus not reached | |

| Provide recognition based on individual VN/T needs | 3.69/5.00 (±0.97) | Consensus not reached | |

| 3. Being trusted with, and involved in, decisions around patient care | Increase veterinarian and leadership awareness of VN/T training and capabilities | 3.27/5.00 (±1.11) | Consensus not reached |

| Develop clear VN/T capability and advancement levels | 3.47/5.00 (±1.11) | Consensus not reached | |

| Build veterinarian trust in VN/Ts through fostering a collaborative culture | 3.07/5.00 (±1.14) | Consensus not reached | |

| Support VN/T professional development and learning | 3.67/5.00 (±1.06) | Consensus not reached |

| Risk Factor | Solution | Perceived Effectiveness Rating (Mean/5.00 (SD)) | Consensus Rating (Participant Agreement %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The workload is too high | Hire more staff | 3.86/5.00 (±0.85) | Effective/very effective (79%) |

| Improve staff retention | 4.57/5.00 (±0.74) | Effective/very effective (93%) | |

| Implement workload management systems to enhance efficiency and communications around workload issues | 4.18/5.00 (±0.55) | Effective/very effective (93%) | |

| Preventative healthcare focus to reduce the number of cases seen | 2.75/5.00 (±0.84) | Ineffective/neutral (75%) | |

| 2. There is a lack of opportunities to utilise skills and knowledge for which veterinary nurses/technicians are trained and qualified | Provide role clarity on skill level and task expectations of VN/Ts and veterinarians | 4.21/5.00 (±0.57) | Effective/very effective (93%) |

| Support veterinarians to delegate tasks to VN/Ts | 4.25/5.00 (±0.70) | Effective/very effective (93%) | |

| Create opportunities for skill utilisation by reducing non-clinical workload and increasing clinical work opportunities | 4.39/5.00 (±0.74) | Effective/very effective (93%) | |

| Implement systems to support delegation | 4.29/5.00 (±0.71) | Effective/very effective (93%) | |

| 3. A negative team culture exists (for example: bullying, gossiping, criticism, or general incivility) | Zero-tolerance to incivility at all levels of the workplace | 4.14/5.00 (±0.79) | Effective/very effective (83%) |

| Promote culture change | 4.38/5.00 (±0.68) | Effective/very effective (90%) | |

| Set clear expectations on expected behaviour | 4.14/5.00 (±0.74) | Effective/very effective (86%) | |

| Provide staff and leadership training and support | 4.28/5.00 (±0.65) | Effective/very effective (90%) | |

| 4. There is a lack of, or unclear, communication from both management and within the team | Increase communication opportunities | 4.23/5.00 (±0.71) | Effective/very effective (85%) |

| Promote and reward good communication | 4.08/5.00 (±0.63) | Effective/very effective (85%) | |

| Develop clear communication protocols and reporting lines | 4.12/5.00 (±0.65) | Effective/very effective (85%) | |

| Utilise different communication methods | 3.96/5.00 (±0.6) | Effective/very effective (88%) | |

| 5. There is poor management/leadership of the team (for example: micromanagement, favouritism, lack of support, or lack of action on team conflict) | Improve leadership recruitment and training processes | 4.38/5.00 (±0.62) | Effective/very effective (93%) |

| Implement systems to support leaders | 4.31/5.00 (±0.54) | Effective/very effective (97%) | |

| Improve workplace communication | 4.45/5.00 (±0.51) | Effective/very effective (100%) | |

| Initiate leadership reviews and accountability | 4.24/5.00 (±0.74) | Effective/very effective (90%) | |

| 6. There is an expectation of working overtime, not having a break, and a general lack of flexibility in rostering | Review and adjust staffing to meet clinic needs | 4.17/5.00 (±0.85) | Effective/very effective (79%) |

| Implement clear break and overtime policies | 4.00/5.00 (±0.89) | Effective/very effective (76%) | |

| Provide leadership and team training | 4.21/5.00 (±0.41) | Effective/very effective (100%) | |

| Review and implement workflow systems to streamline tasks and develop contingency plans | 4.00/5.00 (±0.60) | Effective/very effective (83%) | |

| 7. Remuneration is poor | Offer non-monetary remuneration | 3.48/5.00 (±0.95) | Effective/ neutral (76%) |

| Explore opportunities to increase revenue | 3.79/5.00 (±0.62) | Effective/neutral (90%) | |

| Implement salary banding and progression pathways | 4.17/5.00 (±0.6) | Effective/very effective (90%) | |

| Implement work processes to reduce costs | 4.17/5.00 (±0.66) | Effective/very effective (89%) | |

| 8. There is a lack of opportunity for progression or development | Develop clear progression pathways for VN/Ts | 4.21/5.00 (±0.73) | Effective/very effective (83%) |

| Explore professional growth opportunities | 4.10/5.00 (±0.56) | Effective/very effective (90%) | |

| Provide internal VN/T training and support | 4.28/5.00 (±0.53) | Effective/very effective (97%) | |

| Promote external VN/T training and support | 4.03/5.00 (±0.68) | Effective/very effective (79%) | |

| 9. Having to deal with rude or abusive clients | Provide clear expectations on client conflict management and empower the team | 4.17/5.00 (±1.00) | Effective/very effective (83%) |

| Create workplace support systems for VN/Ts faced with client abuse | 4.10/5.00 (±0.77) | Effective/very effective (83%) | |

| Prepare and train the team for conflict situations | 4.14/5.00 (±0.74) | Effective/very effective (79%) | |

| Communicate clear behavioural expectations to clients | 3.72/5.00 (±1.19) | Consensus not reached | |

| 10. There is a lack of appreciation, feeling valued, or being heard, by management | Implement VN/T recognition systems | 3.69/5.00 (±0.85) | Effective/neutral (76%) |

| Increase communication channels between management and VN/Ts | 4.03/5.00 (±0.63) | Effective/very effective (83%) | |

| Provide support and training for leaders | 4.15/5.00 (±0.6) | Effective/very effective (89%) | |

| Identify what appreciation looks like for individuals | 4.45/5.00 (±0.69) | Effective/very effective (90%) |

| Risk factor 1: The workload is too high | ||

| Proposed solutions | Effectiveness rating (mean/5.00 (SD)) | Examples of actions that may be implemented include |

| Improve staff retention | Very high (4.57/5.00 (±0.74)) | Short term: Implement clear job goal and progression tracking; improve leader-staff communication; implement exit and stay interviews |

| Medium term: Improve workplace wellbeing; improve leader responsiveness; empower staff to have a voice; provide leadership and team training on psychosocial hazards and occupational health and safety (OHS) responsibilities | ||

| Long term: Improve workplace culture; provide training and support to improve leadership skills; provide staff training and increase VN/T utilisation | ||

| Implement workload management systems to enhance efficiency and communications around workload issues | Very high (4.18/5.00 (±0.55)) | Short term: Develop clear policies and standard operating procedures (SOPs) to provide guidance on caseload and booking protocols; hold regular team meetings; review current systems to improve workflow |

| Hire more staff | High (3.86/5.00 (±0.85)) | Short term: Determine skill gaps and capacity to support training of unskilled VN/Ts; hire more VN/Ts and/or non-VN/T support staff to reduce non-clinical workload—level of experience should be determined by needs assessment |

| Medium term: Implement robust induction and training processes | ||

| Risk factor 2: There is a lack of opportunities to utilise skills and knowledge for which veterinary nurses/technicians are trained and qualified | ||

| Proposed solutions | Effectiveness rating (mean/5.00 (SD)) | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Create opportunities for skill utilisation by reducing non-clinical workload and increasing clinical work opportunities | Very high (4.39/5.00 (±0.74)) | Short term: Introduce VN/T clinics |

| Medium term: Utilise technology to manage non-clinical workload—ensuring support is provided; implement progression pathways for VN/Ts | ||

| Implement systems to support delegation | Very high (4.29/5.00 (±0.71)) | Short term: Implement VN/T-to-patient and veterinarian ratios; develop clear SOPs for clinical tasks; introduce team rounds to promote collaboration and increase veterinarian awareness and trust of VN/T capabilities |

| Medium term: Implement mentoring programs; hire/utilise non-VN/T support staff for non-clinical tasks | ||

| Support veterinarians to delegate tasks to VN/Ts | Very high (4.25/5.00 (±0.70)) | Short term: Provide support from leadership |

| Medium term: Provide veterinarian training on VN/T education and relevant legislation/regulations; provide delegation training | ||

| Provide role clarity on skill level and task expectations of VN/Ts and veterinarians | Very high (4.21/5.00 (±0.57)) | Short term: Develop clear SOPs outlining veterinary and VN/T tasks and responsibilities—specific to experience/specialisation |

| Medium term: Introduce VN/T levelling system based on education and experience | ||

| Risk factor 3: A negative team culture exists (for example: bullying, gossiping, criticism, or general incivility) | ||

| Proposed solutions | Effectiveness rating (mean/5.00 (SD)) | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Promote culture change | Very high (4.38/5.00 (±0.68)) | Short term: Develop team vision and values collaboratively; provide support from leadership; conduct anonymous surveys to measure staff perceptions of culture and identify issues |

| Medium term: Introduce culture officer role; promote regular and transparent communication; support low level resolution between individuals; leadership team to model positive culture | ||

| Long term: Promote psychological safety | ||

| Provide staff and leadership training and support | Very high (4.28/5.00 (±0.65)) | Medium term: Provide dedicated time and training for leadership and staff on areas such as communication skills, conflict management, mental health first aid, civility training, human resources management, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) awareness, local employment laws |

| Set clear expectations on expected behaviour | Very high (4.14/5.00 (±0.74)) | Short term: Develop clear policies and definitions of bullying; introduce a code of conduct |

| Medium term: Implement performance improvement plans; implement disciplinary procedures | ||

| Zero-tolerance to incivility at all levels of the workplace | Very high (4.14/5.00 (±0.79)) | Short term: Identify causes of incivility and address issues early; apply zero tolerance policies equitably across all roles |

| Medium term: Support calling in unacceptable behaviour; implement disciplinary procedures and termination if necessary | ||

| Risk factor 4: There is a lack of, or unclear, communication from both management and within the team | ||

| Proposed solutions | Effectiveness rating (mean/5.00 (SD)) | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Increase communication opportunities | Very high (4.23/5.00 (±0.71)) | Short term: Introduce interdisciplinary and individual team meetings; implement team huddles and debriefs at the start and end of the day; implement a leadership open door policy; create feedback opportunities |

| Develop clear communication protocols and reporting lines | Very high (4.12/5.00 (±0.65)) | Short term: Implement clear reporting lines; establish a single source of information; develop communication templates; ensure availability of recordings or minutes for those unable to attend; provide training in new protocols and systems |

| Promote and reward good communication | Very high 4.08/5.00 (±0.63)) | Medium term: Promote leadership modelling of good communication; provide communication training; celebrate effective communication |

| Long term: Promote psychological safety | ||

| Utilise different communication methods | High (3.96/5.00 (±0.60)) | Short term: Seek input on individual preferences for communication; consider personality types, e.g., introverts and adapt bidirectional communication accordingly; implement anonymous and identified feedback systems |

| Medium term: Utilise technology to increase accessibility—ensuring support is provided; implement a centralised communication hub | ||

| Risk factor 5: There is poor management/leadership of the team (for example: micromanagement, favouritism, lack of support, or lack of action on team conflict) | ||

| Proposed solutions | Effectiveness rating (mean/5.00 (SD)) | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Improve workplace communication | Very high (4.45/5.00 (±0.51)) | Short term: Implement feedback systems; hold regular team meetings; promote transparency |

| Long term: Promote psychological safety | ||

| Improve leadership recruitment and training processes | Very high (4.38/5.00 (±0.62)) | Short term: Adopt recruitment strategies focused on leadership and clinical skills/experience not just clinical seniority |

| Medium term: Implement succession planning | ||

| Long term: Provide ongoing training in leadership and human resource management | ||

| Implement systems to support leaders | Very high (4.31/5.00 (±0.54)) | Short term: Promote empowerment and support from upper management; Promote role modelling and introduce mentorship programs |

| Medium term: Implement allocated and protected admin time for those in mixed leadership/clinical roles; implement management levelling system to support development | ||

| Initiate leadership reviews and accountability | Very high (4.24/5.00 (±0.74)) | Short term: Develop and communicate clear expectations; implement structured leadership review systems such as 360 reviews |

| Medium term: Implement performance management processes | ||

| Risk factor 6: There is an expectation of working overtime, not having a break, and a general lack of flexibility in rostering | ||

| Proposed solutions | Effectiveness rating (mean/5.00 (SD)) | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Provide leadership and team training | Very high (4.21/5.00 (±0.41)) | Medium term: Provide dedicated time for team training on areas such as communication and teamwork, wellness, workplace legislation; provide dedicated time for leadership training on turnover costs and effective workload management; implement cross-training of team skills to enable greater support |

| Regularly review and adjust staffing to meet clinic needs | Very high (4.17/5.00 (±0.85)) | Short term: Implement an on-call per diem roster in the event overtime is required |

| Medium term: Perform a needs analysis to determine gaps; hire more VN/Ts and/or non-VN/T support staff to meet workload, including flexible or part time roles to increase coverage at busy periods and float VN/Ts to cover breaks | ||

| Review and implement workflow systems to streamline tasks and develop contingency plans | Very high (4.00/5.00 (±0.60)) | Short term: Implement limited service/bypass protocols (seeing only critical patients and redirecting non-critical cases elsewhere); develop clear policies to prevent overbooking; hold morning team huddles to plan workflow; utilise rostering software to assist; utilise telemedicine and triaging support services |

| Medium term: Develop team pipelines to improve workflow; partner with local clinics to share relief or floating VN/Ts | ||

| Implement clear break and overtime policies | Very high (4.00/5.00 (±0.89)) | Short term: Introduce scheduled break times, or break guidelines to be coordinated by shift lead; implement overtime bonus pay structures |

| Medium term: Cultivate a casual VN/T bank for last minute support | ||

| Risk factor 7: Remuneration is poor | ||

| Proposed solutions | Effectiveness rating (mean/5.00 (SD)) | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Implement salary banding and progression pathways | Very high (4.17/5.00 (±0.60)) | Short term: Develop clear job descriptions and skill levels—ensuring growth is not limited to title; promote transparency around salary banding as well as clinic running costs |

| Medium term: Implement pay commensurate with skill level; develop progression pathways and support to increase responsibility and skill level | ||

| Implement work processes to reduce costs | Very high (4.17/5.00 (±0.66)) | Medium term: Utilise technology to automate routine tasks—ensuring support is provided; implement appropriate utilisation of VN/Ts to increase veterinarian capacity |

| Explore opportunities to increase revenue | High (3.79/5.00 (±0.62)) | Short term: Ensure correct charging; increase prices; promote client education on pet insurance |

| Medium term: Introduce new services (e.g., VN/T clinics, telehealth); conduct budget forecasting | ||

| Offer non-monetary remuneration | High (3.48/5.00 (±0.95)) | Short term: Develop a structured and equitable system |

| Medium term: Determine individualised options in consultation with staff members as suited to their needs (e.g., childcare support, travel vouchers, time off for study) | ||

| Risk factor 8: There is a lack of opportunity for progression or development | ||

| Proposed solutions | Effectiveness rating (mean/5.00 (SD)) | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Provide internal VN/T training and support | Very high (4.28/5.00 (±0.53)) | Short term: Implement individual development plans; support time off for study |

| Medium term: Implement a development and training officer role; provide leadership training; develop mentoring/coaching programs | ||

| Develop clear progression pathways for VN/Ts | Very high (4.21/5.00 (±0.73)) | Short term: Develop clear progression bands; develop clear VN/T job descriptions with training to support growth within the clinic |

| Medium term: Support both leadership and non-leadership progression pathways; implement growth lattices—supporting both vertical and horizontal development | ||

| Explore professional growth opportunities | Very high (4.10/5.00 (±0.56)) | Short term: Identify areas for increased responsibility |

| Medium term: Support undertaking specialised qualifications that can be utilised by the clinic; develop specific roles that match individuals’ interests or skills | ||

| Promote external VN/T training and support | Very high (4.03/5.00 (±0.68)) | Short term: Identify networking opportunities; signpost funding opportunities and access to CE; identify and approach other industry members for mentoring (e.g., VTS) |

| Medium term: Establish a continuing education funding program with requirement for funding recipients to share new knowledge with the team | ||

| Risk factor 9: Dealing with clients expressingrude or abusive behaviours | ||

| Proposed solutions | Effectiveness rating (mean/5.00 (SD)) | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Provide clear expectations on client conflict management and empower the team | Very high (4.17/5.00 (±1.00)) | Short term: Promote zero tolerance for abuse of staff; develop clear guidelines on what constitutes acceptable and non-acceptable behaviour; develop guidelines and provide training on when to escalate issues; develop and provide training on communication protocols for conflict situations |

| Prepare and train the team for conflict situations | Very high (4.14/5.00 (±0.74)) | Short term: Identify and address issues that contribute to poor client experience; ensure staff are never rostered alone; install security systems (e.g., CCTV, duress alarms); develop client information on external financial and emotional support services |

| Medium term: Provide regular staff training in de-escalation and emotional intelligence | ||

| Create workplace support systems for VN/Ts faced with client abuse | Very high (4.10/5.00 (±0.77)) | Short term: Provide —and ensure access to—leadership support; implement debriefs after difficult interactions; Implement reporting systems for incidents |

| Medium term: Employ social workers in the team with training to manage and support distressed clients | ||

| Long term: Promote teamwork and support through improving workplace culture—refer to risk factor 3 | ||

| Communicate clear behavioural expectations to clients | High (3.72/5.00 (±1.19)) | Short term: Develop code of conduct contracts for new and/or existing clients outlining two-way expectations of the client-clinic relationship; introduce waiting room signage; provide clear and transparent information on costs and wait times; outline the consequences of abusing staff |

| Risk factor 10: There is a lack of appreciation, feeling valued, or being heard, by management | ||

| Proposed solutions | Effectiveness rating (mean/5.00 (SD)) | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Identify what appreciation looks like for individuals | Very high (4.45/5.00 (±0.69)) | Short term: Survey the team; implement individual development plans; Include individual motivator discussion as part of new staff inductions |

| Medium term: Provide dedicated time for leaders to spend with staff | ||

| Provide support and training for leaders | Very high (4.15/5.00 (±0.60)) | Medium term: Provide training on areas such as effective communication, emotional intelligence, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), culture, intrinsic motivators; develop mentoring and peer group programs |

| Increase communication channels between management and VN/Ts | Very high (4.03/5.00 (±0.63)) | Short term: Implement feedback systems; hold regular meetings; establish preferred communication channels in consultation with the team; Implement open door policies |

| Implement VN/T recognition systems | High (3.69/5.00 (±0.85)) | Short term: Introduce initiatives in collaboration with the team such as newsletters, VN/T of the month, long service awards, staff appreciation days; include recognition as a standing agenda item in meetings |

| Medium term: Establish a staff appreciation committee; establish a staff appreciation fund | ||

| Effectiveness rating scored out of 5: Very low = 0–1; Low = 1.1–2; Neutral = 2.1–3; High = 3.1–4; Very high = 4.1–5 Duration of implementation: Short term = 0–6 months; Medium term = 6–12 months; Long term = 1–2 years+ Note: Success of many of these strategies relies on effective planning and implementation. If existing expertise is not available within the clinic, the use of—or communication with—external consultants is suggested to increase chance of success. | ||

| Protective Factor 1: Having some control over the schedule or expected tasks | |

| Proposed strategies | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Adopt a collaborative team scheduling approach | VN/T representation in management decision making; morning team huddles to plan tasks, breaks, and teamwork; support innovation to improve scheduling or workflow practices |

| Upskill and cross-train VN/Ts | Increase capacity to perform in all VN/T roles; build confidence to work autonomously; cross-train to increase opportunity to swap shifts |

| Develop clear expectations for VN/T tasks and roles | Collaborative development of VN/T shift descriptions with tasks and skill levels outlined |

| Implement work systems to enhance clarity and communications around scheduling | Clear booking policies to prevent overbooking; break and overtime policies; seek VN/T feedback on scheduling issues and collaboratively problem solve |

| Protective Factor 2: Knowledge of having a positive impact on a patient or client | |

| Proposed strategies | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Implement peer feedback systems | Kudos boards; team meeting shout outs; communication systems to pass feedback up to management; make acknowledgement part of team huddles and debriefs |

| Encourage clear and open communication within the team | Improve culture around good communication; leadership modelling of good communication; create regular and easy feedback systems and habits |

| Provide recognition based on individual VN/T needs | Survey the team to determine preferences; public vs. private feedback; increase team and leadership awareness of generational and career stage influences on individual needs |

| Protective Factor 3: Being trusted with, and involved in, decisions around patient care | |

| Proposed strategies | Examples of actions that may be implemented include: |

| Increase veterinarian and leadership awareness of VN/T training and capabilities | Encourage active involvement of VN/Ts in case discussions providing an opportunity to demonstrate knowledge; education of veterinarians and leaders on VN/T education levels and professional regulation |

| Develop clear VN/T capability and advancement levels | Clear guidelines around skills and abilities expected at each level; conduct VN/T competency assessments to progress to next level; develop a spectrum of care chart to clearly outline clinical expectations at each level |

| Build veterinarian trust in VN/Ts through fostering a collaborative culture | Psychological safety; all team patient rounds; veterinarian to VN/T mentoring and reverse mentoring programs; encourage questions and discussion for learning; team debriefing; leadership support; team consulting; collaborative patient care plans |

| Support VN/T professional development and learning | Individual development plans; in house training; journal clubs; shadowing shifts with experienced VN/Ts; provide clear patient parameter ranges and alert guidelines to inexperienced VN/Ts |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chapman, A.J.; Bennett, P.C.; Rohlf, V.I. Workplace Strategies to Reduce Burnout in Veterinary Nurses and Technicians: A Delphi Study. Animals 2025, 15, 1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15091257

Chapman AJ, Bennett PC, Rohlf VI. Workplace Strategies to Reduce Burnout in Veterinary Nurses and Technicians: A Delphi Study. Animals. 2025; 15(9):1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15091257

Chicago/Turabian StyleChapman, Angela J., Pauleen C. Bennett, and Vanessa I. Rohlf. 2025. "Workplace Strategies to Reduce Burnout in Veterinary Nurses and Technicians: A Delphi Study" Animals 15, no. 9: 1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15091257

APA StyleChapman, A. J., Bennett, P. C., & Rohlf, V. I. (2025). Workplace Strategies to Reduce Burnout in Veterinary Nurses and Technicians: A Delphi Study. Animals, 15(9), 1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15091257