Emotional Welfare and Its Relationship with Social Interactions and Physical Conditions of Finishing Pigs in Lairage at the Slaughterhouse

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Behavior Assessment (QBA)

2.2. Training of the Observer

2.3. Behavioral Assessment

2.4. Physical Examination

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saraiva, S.; Santos, S.; García-Díez, J.; Simões, J.; Saraiva, C. Comparative analysis of animal welfare in three broiler slaughterhouses and associated farms with unsatisfactory slaughterhouse results. Animals 2024, 14, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, J.; Krieter, J.; Büttner, K.; Wilder, T.; Hasler, M.; Bussemas, R.; Witten, S.; Czycholl, I. Relationship between animal-based on-farm indicators and meat inspection data in pigs. Porc. Health Manag. 2024, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čobanović, N.; Čalović, S.; Suvajdžić, B.; Grković, N.; Stanković, S.D.; Radaković, M.; Spariosu, K.; Karabasil, N. Consequences of Transport Conditions on the Welfare of Slaughter Pigs with Different Health Status and RYR-1 Genotype. Animals 2024, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welfare Quality® Consortium. Welfare Quality® Assessment Protocol for Pigs (Sows and Piglets, Growing and Finishing Pigs); Welfare Quality® Consortium: Lelystad, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rey-Salgueiro, L.; Martinez-Carballo, E.; Fajardo, P.; Chapela, M.J.; Espiñeira, M.; Simal-Gandara, J. Meat quality about swine well-being after transport and during lairage at slaughterhouse. Meat Sci. 2018, 142, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, B.P. Effect of rearing system and mixing at loading on transport and lairage behavior and meat quality: Comparison of outdoor and conventionally raised pigs. Animal 2008, 2, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, C.A. A review of welfare in cattle, sheep, and pig lairages, with emphasis on stocking rates, ventilation, and noise. Anim. Welf. 2008, 17, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eath, R.B.; Turner, S.P.; Kurt, E.; Evans, G.; Thölking, L.; Looft, H.; Wimmers, K.; Murani, E.; Klont, R.; Foury, A.; et al. Pigs’ aggressive temperament affects pre-slaughter mixing aggression, stress, and meat quality. Animal 2010, 4, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geverink, N.A.; Engel, B.; Lambooij, E.; Wiegant, V.M. Observations on behavior and skin damage of slaughter pigs and treatment during lairage. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 50, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, L.; Van de Perre, V.; Permentier, L.; De Bie, S.; Verbeke, G.; Geers, R. Pre-slaughter handling and pork quality. Meat Sci. 2015, 100, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faucitano, L. Preslaughter handling practices and their effects on animal welfare and pork quality. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerlink, I.; Peijnenburg, M.; Wemelsfelder, F.; Turner, S.P. Emotions after victory or defeat assessed through qualitative behavioral assessment, skin lesions, and blood parameters in pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 183, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geverink, N.A.; Bühnemann, A.; van de Burgwal, J.A.; Lambooij, E.; Blokhuis, H.J.; Wiegant, V.M. Responses of slaughter pigs to transport and lairage sounds. Physiol. Behav. 1998, 63, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliotti, L.; Benvenuti, M.N.; Giannarelli, A.; Mariti, C.; Gazzano, A. Effect of different environment enrichments on behavior and social interactions in growing pigs. Animals 2019, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibach, S.; Chou, J.-Y.; Battini, M.; Parsons, T.D. A systematic approach to defining and verifying descriptors used in the Qualitative Behavioral Assessment of sows. Anim. Welf. 2024, 33, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeates, J.W.; Main, D.C.J. Assessment of Positive Welfare: A Review. Vet. J. 2008, 175, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boissy, A.; Manteuffel, G.; Jensen, M.B.; Moe, R.O.; Spruijt, B.; Keeling, L.J.; Winckler, C.; Forkman, B.; Dimitrov, I.; Langbein, J.; et al. Assessment of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, D.; Manteca, X.; Velardo, A.; Almau, A. Assessment of Animal Welfare through Behavioural Parameters in Iberian Pigs in Intensive and Extensive Conditions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 131, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, O.; O’Driscoll, K.; Baxter, E.; Boyle, L. Artificial Rearing Affects the Emotional State and Reactivity of Pigs Post-Weaning. Anim. Welf. 2019, 28, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.A.; Clarke, T.; Wickham, S.L.; Stockman, C.A.; Barnes, A.L.; Collins, T.; Miller, D.W. The Contribution of Qualitative Behavioural Assessment to Appraisal of Livestock Welfare. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2016, 56, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunberg, E.; Wallenbeck, A.; Keeling, L.J. Tail biting in fattening pigs: Associations between frequency of tail biting and other abnormal behaviors. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 133, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, R.C.; Wood-Gush, D.G.M.; Hall, J.W. Playful behavior of piglets. Behav. Process. 1988, 17, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinerová, K.; Parker, S.E.; Brown, J.A.; Seddon, Y.M. The Promotion of Play Behaviour in Grow-Finish Pigs: The Relationship between Behaviours Indicating Positive Experience and Physiological Measures. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 275, 106263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, A.; Carpentier, L.; Piette, D.; Boyle, L.A.; Berckmans, D.; Norton, T. An ethogram of biter and bitten pigs during an ear-biting event: First step in the development of a precision livestock farming tool. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 215, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Jansen, H.; Amezcua, M.D.; O’Sullivan, T.L.; Niel, L.; Shoveller, A.K.; Friendship, R.M. Tail-biting in pigs: A scoping review. Animals 2021, 11, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, L.A.; Edwards, S.A.; Bolhuis, J.E.; Pol, F.; Šemrov, M.Z.; Schütze, S.; Nordgreen, J.; Bozakova, N.; Sossidou, E.N.; Valros, A. The evidence for a causal link between disease and damaging behavior in pigs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 771682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telkänranta, H.; Swan, K.; Hirvonen, H.; Valros, A. Chewable materials before weaning reduce tail biting in growing pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 157, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.B.; Herskin, M.S.; Forkman, B.; Pedersen, L.J. Effect of Increasing Amounts of Straw on Pigs’ Explorative Behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 171, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studnitz, M.; Jensen, M.B.; Pedersen, L.J. Why Do Pigs Root and in What Will They Root? A Review on the Exploratory Behaviour of Pigs in Relation to Environmental Enrichment. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 107, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, I.C.; Ekkel, E.D.; Van de Burgwal, J.A.; Lambooij, E.; Korte, S.M.; Ruis, M.A.W.; Koolhaas, J.M.; Blokhuis, H.J. Effects of straw bedding on physiological responses to stressors and behavior in growing pigs. Physiol. Behav. 1998, 64, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, A.; Velarde, A. Lairage and handling. In Animal Welfare at Slaughter; Velarde, A., Raj, M., Eds.; 5m Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2016; pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Desire, S.; Turner, S.P.; D’Eath, R.B.; Doeschl-Wilson, A.B.; Lewis, C.R.G.; Roehe, R. Analysis of the phenotypic link between behavioral traits at mixing and increased long-term social stability in group-housed pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 166, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arey, D.S.; Franklin, M.F. Effects of Straw and Unfamiliarity on Fighting Between Newly Mixed Growing Pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1995, 45, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydhmer, L.; Zamaratskaia, G.; Andersson, H.K.; Algers, B.; Guillemet, R.; Lundström, K. Aggressive and sexual behavior of growing and finishing pigs reared in groups, without castration. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. A—Anim. Sci. 2006, 56, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Tilbrook, A.J. Sexual behavior of male pigs. Horm. Behav. 2007, 52, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driessen, B.; Van Beirendonck, S.; Buyse, J. Effects of transport and lairage on the skin damage of pig carcasses. Animals 2020, 10, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minero, M.; Dalla Costa, E.; Dai, F.; Murray, L.A.; Canali, E.; Wemelsfelder, F. Use of Qualitative Behavior Assessment as an indicator of welfare in donkeys. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 174, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptor | Definition |

|---|---|

| Active | Not resting or sleeping and can be performing any type of motor activity. |

| Agitated | Display a lot of movement or is in a hurry to carry out an action or change actions. |

| Apathetic | Lacking in energy, vigor, and enthusiasm. Despondent and passive, not engaging with any particular element in their surroundings. |

| Bored | Unstimulated and uninterested. |

| Calm | Quiet, placid, and without strong emotions. |

| Content | Signs of overall satisfaction, peace, and comfort. |

| Distressed | Actively attempting to escape, avoid stressors, or withdraw completely; potentially experiencing panic, anxiety, or pain. |

| Sociable | Enjoying what they are doing, and interacting with environmental resources and their surroundings. |

| Friendly | Calm approaches and gentle social interactions in their environment. |

| Fearful | Startled, afraid, or terrified of a situation and may freeze or actively try to escape or retreat. |

| Frustrated | Discouraged due to repeated unsuccessful attempts to achieve or change something, hindered from reaching a goal, or consistently failing a task. |

| Happy | Joyful, cheerful, and untroubled. |

| Indifferent | Lacking interest in their environment and showing little to no attention or reaction to stimuli. |

| Inquisitive | Showing curiosity by exploring their surroundings, approaching objects, and investigating everything around. |

| Irritable | Easily reactive in a negative way towards any stimulus; uneasy and may be quick to flinch or show signs of annoyance. |

| Lively | Energetic, full of vigor, observant of their surroundings, and may be quick to move. |

| Playful | Fun-loving and gleeful. They may run, hop, spin, or manipulate items. |

| Positively occupied | Engaged in an activity they enjoy or require; fully immersed in their surroundings with focused, purposeful, and constructive behaviour. |

| Relaxed | At ease with their surroundings. |

| Tense | Alert and uneasy, with a worried or cautious expression, and a stiff posture. |

| Behavior Parameters | Observed Behaviors |

|---|---|

| Aggression | Two or more pigs are fighting; biting tails; biting ears. |

| Tail or ear manipulation | A pig is touching another pig’s tail or ear with its snout. |

| Mounting | Climbing onto another animal’s back. |

| Exploratory behavior in pens | Exploring the floor of the pen with the snout. |

| Exploratory behavior in the environment | Catching water in the air with the mouth. |

| Exploratory behavior with enrichment materials | Environmental interaction with suspended balls. |

| Stereotypes | Chewing/masticating without substrate; biting bars. |

| Emotions (+) | Active | Calm | Content | Happy | Lively | Inquisitive | Sociable | Friendly | Playful | Posit Occupied | Relaxed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | ||||||||||||

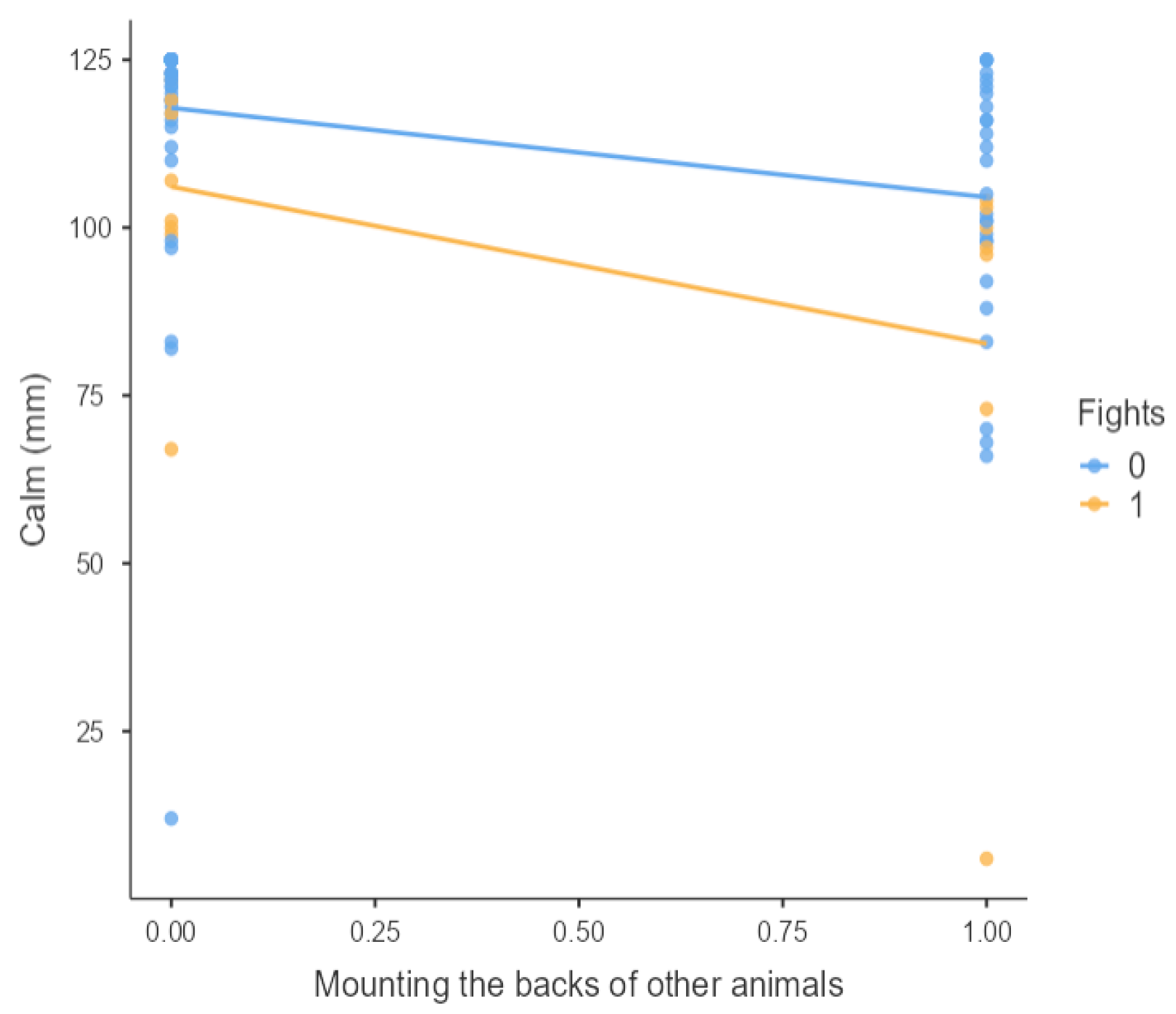

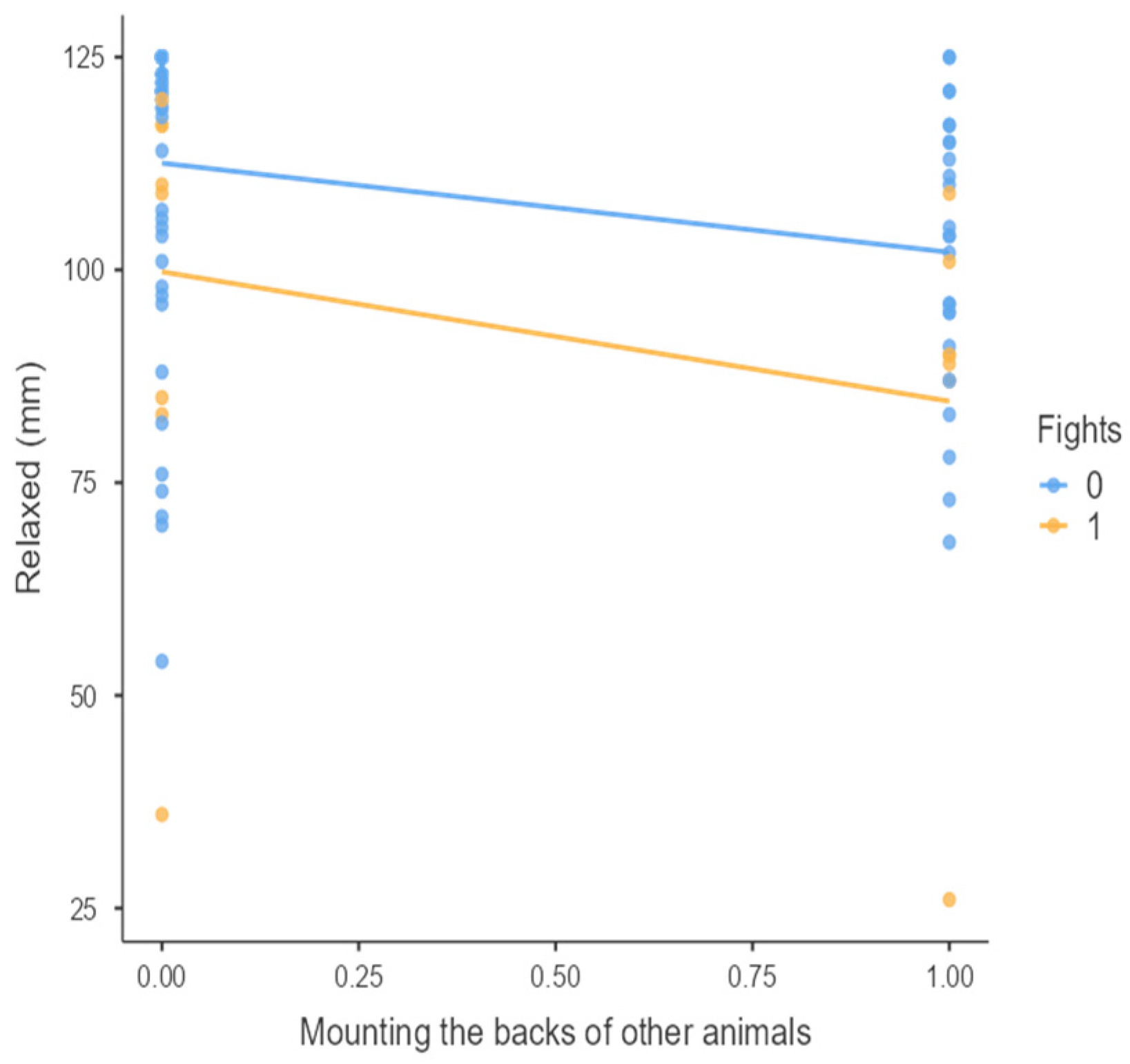

| Fighting | 0.215 | −0.305 ** | −0.303 ** | −0.148 | 0.169 | 0.176 | 0.017 | −0.004 | 0.017 | 0.083 | −0.288 ** | |

| Ear biting | −0.021 | 0.162 | −0.078 | 0.112 | −0.205 | −0.057 | −0.053 | −0.007 | 0.014 | 0.110 | 0.053 | |

| Tail biting | 0.262 | 0.058 | −0.336 ** | 0.162 | 0.030 | 0.102 | 0.133 | 0.133 | 0.288 ** | 0.296 ** | −0.165 | |

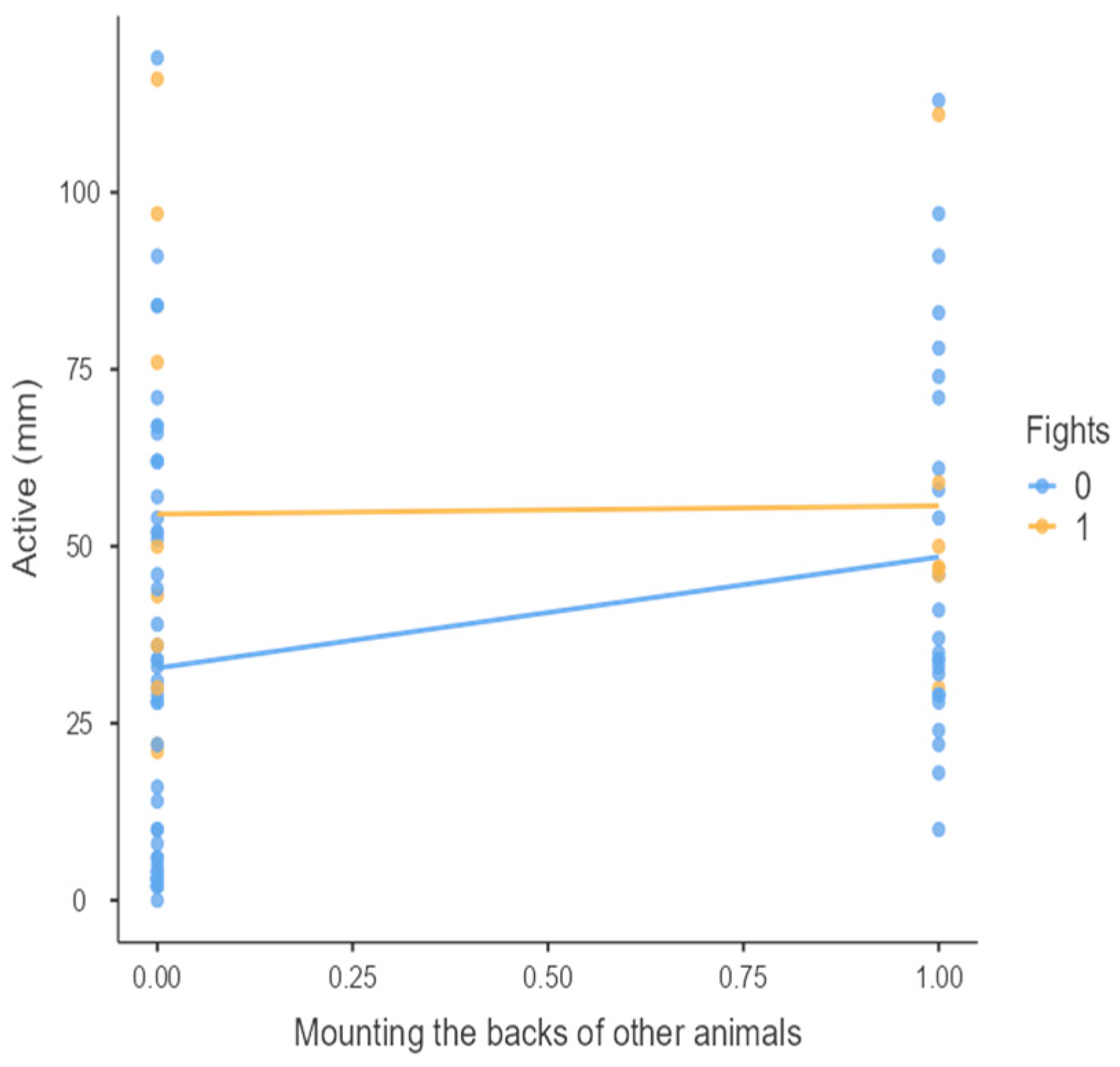

| Mounting on the back of other animals | 0.225 | −0.358 *** | −0.233 | −0.011 | 0.071 | 0.093 | 0.042 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.047 | −0.382 *** | |

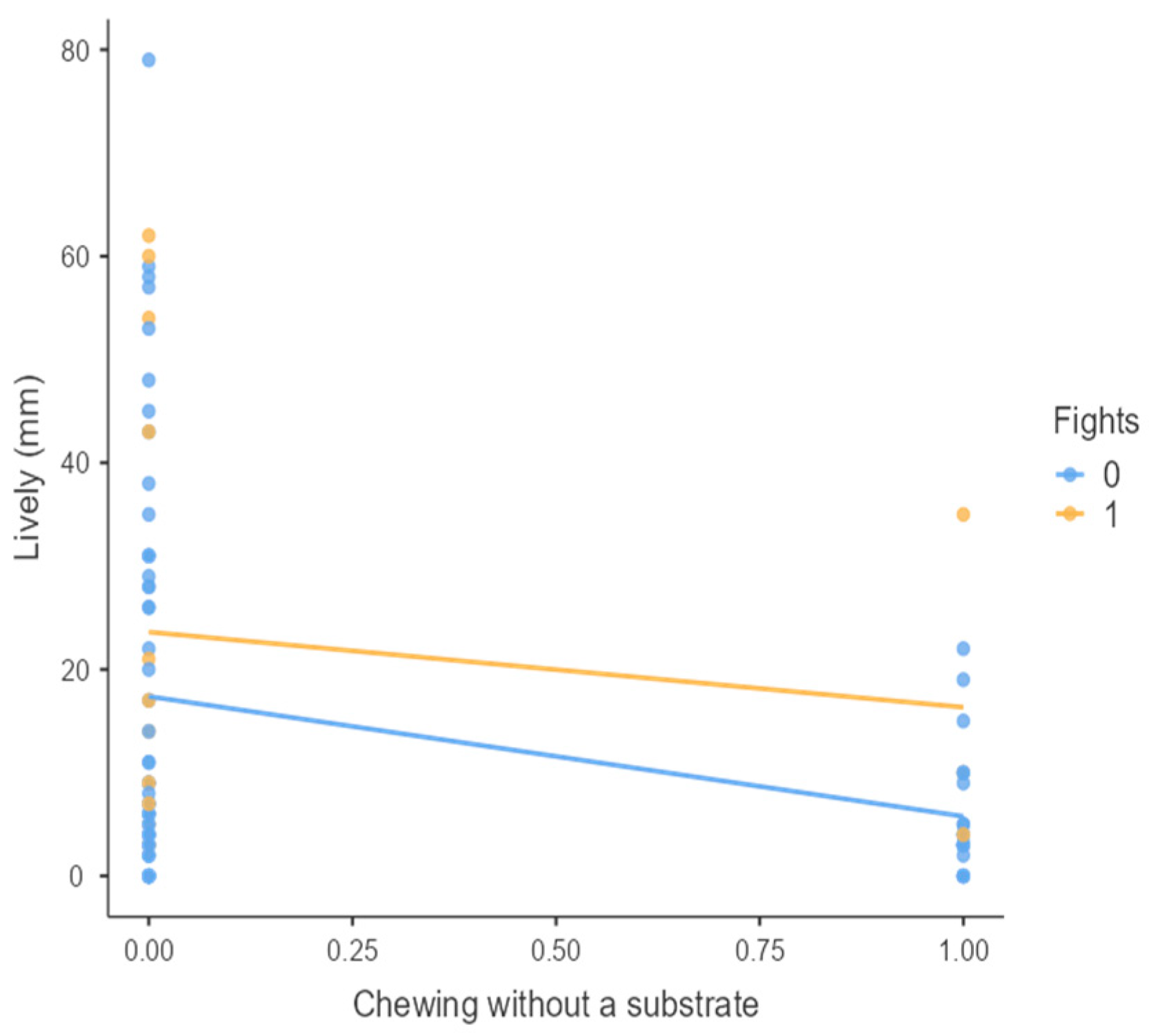

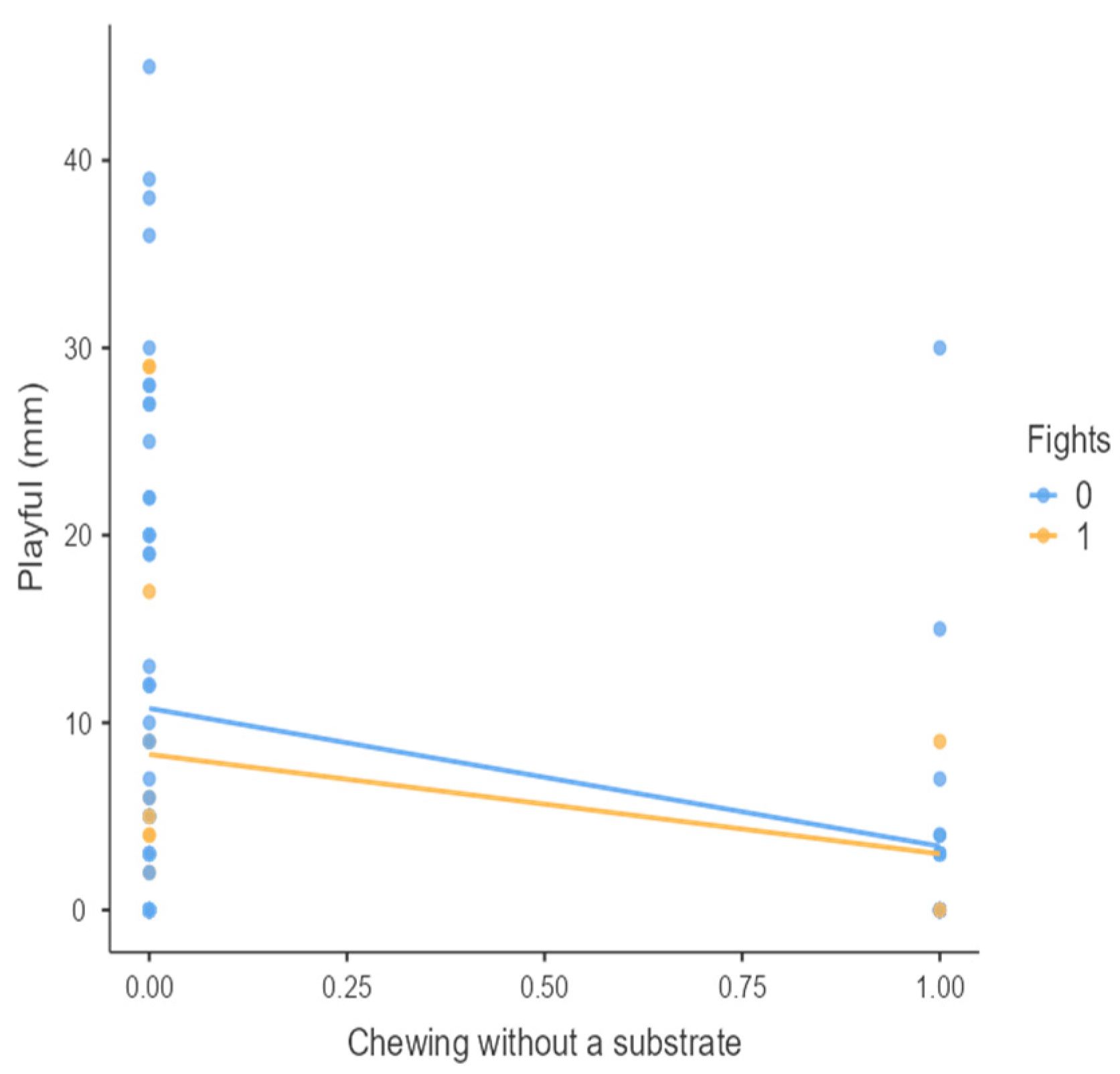

| Chewing without a substrate | −0.193 | 0.155 | 0.048 | −0.210 | −0.281 | −0.116 | −0.229 | −0.247 | −0.286 ** | −0.146 | 0.113 | |

| Emotions (−) | Agitated | Apathetic | Bored | Tense | Distressed | Fearful | Frustrated | Indifferent | Irritable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | ||||||||||

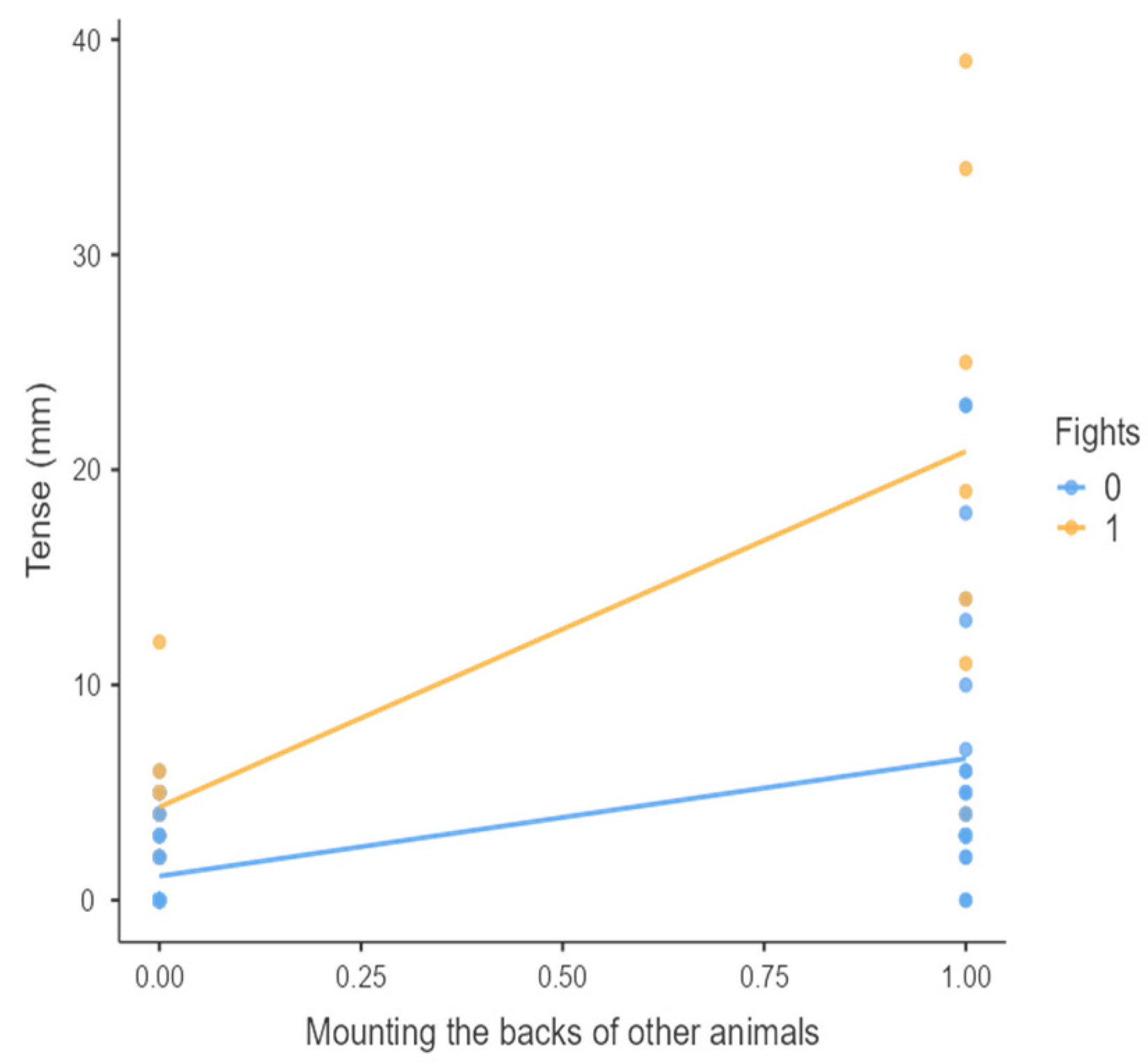

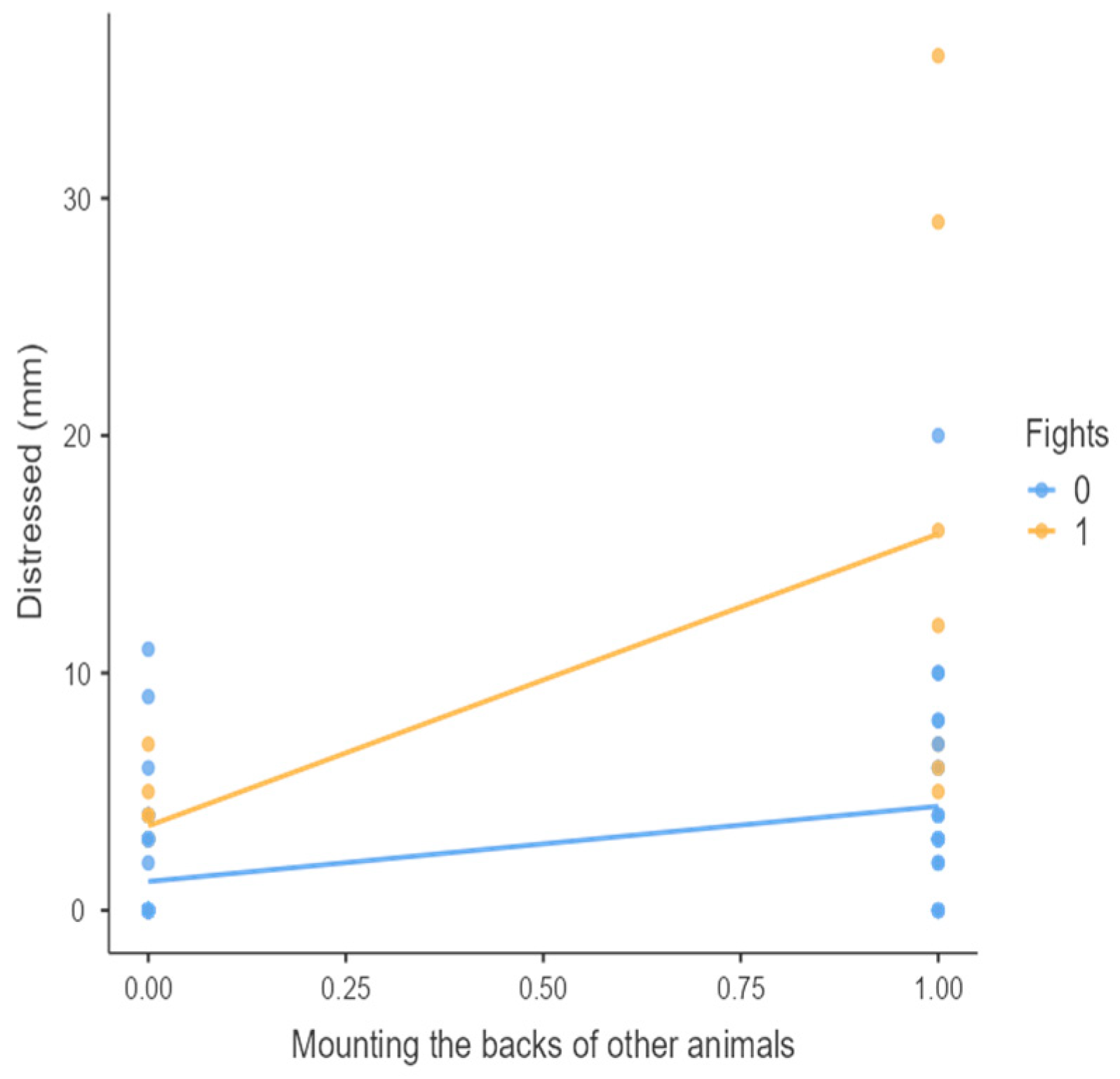

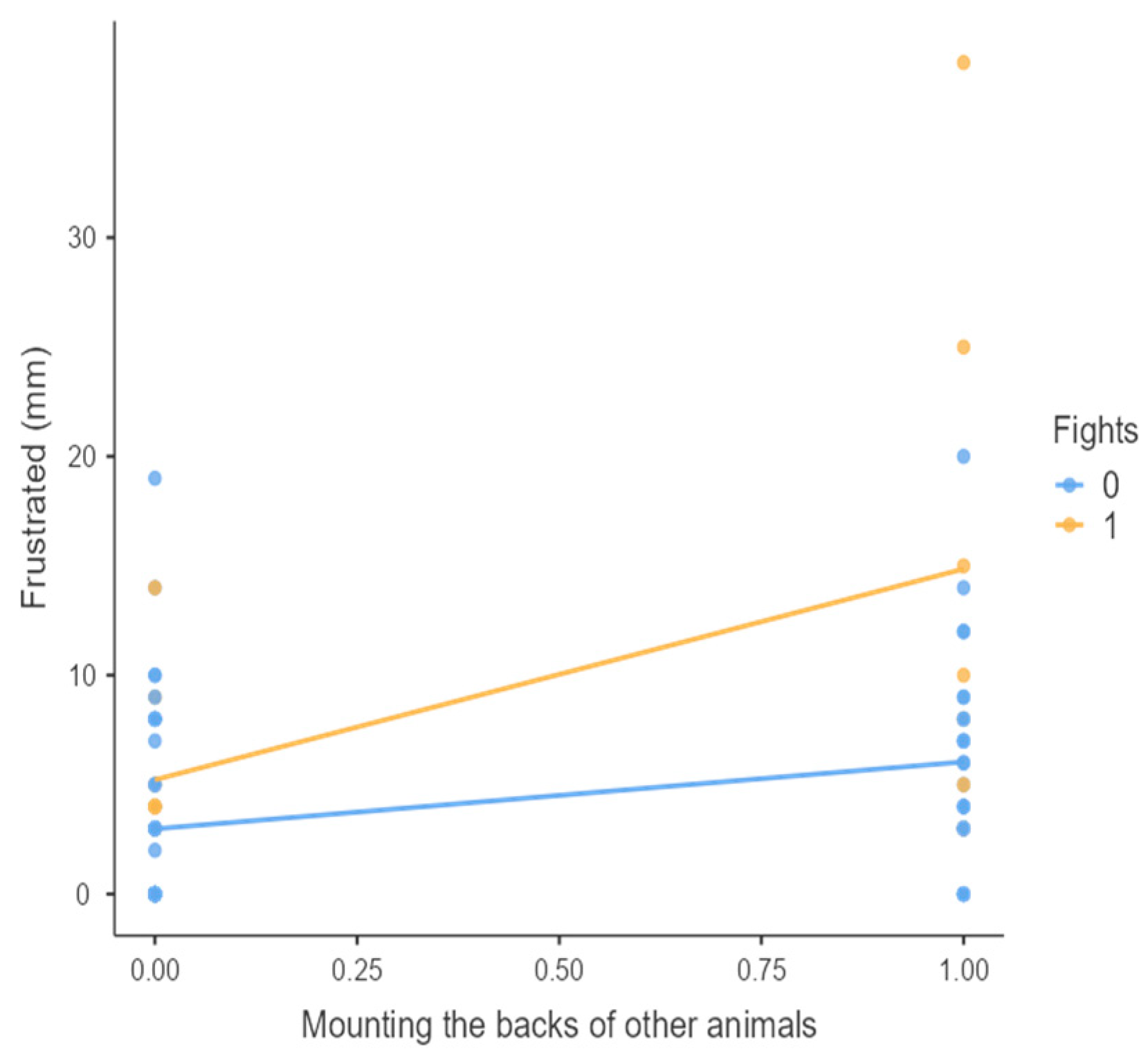

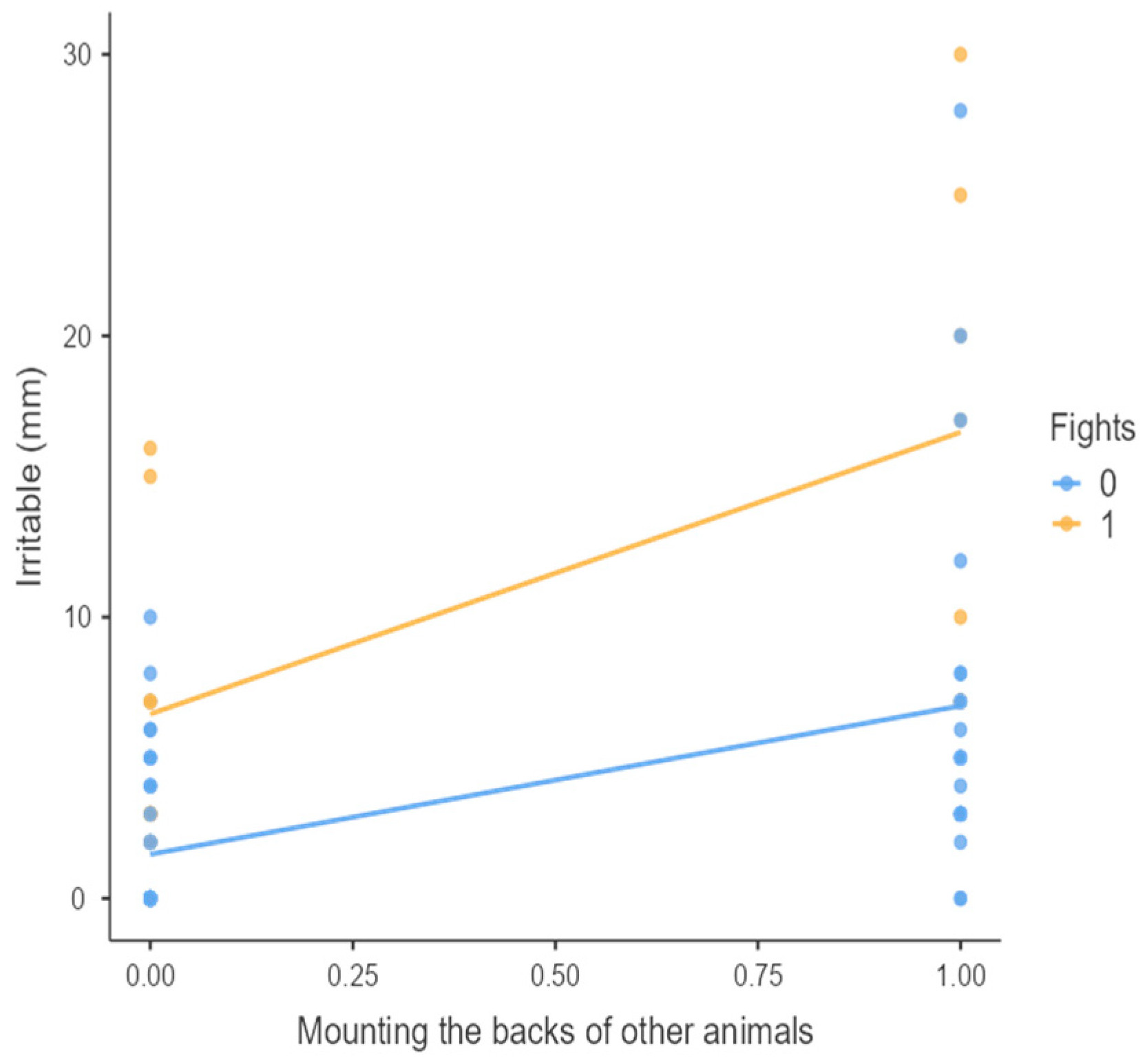

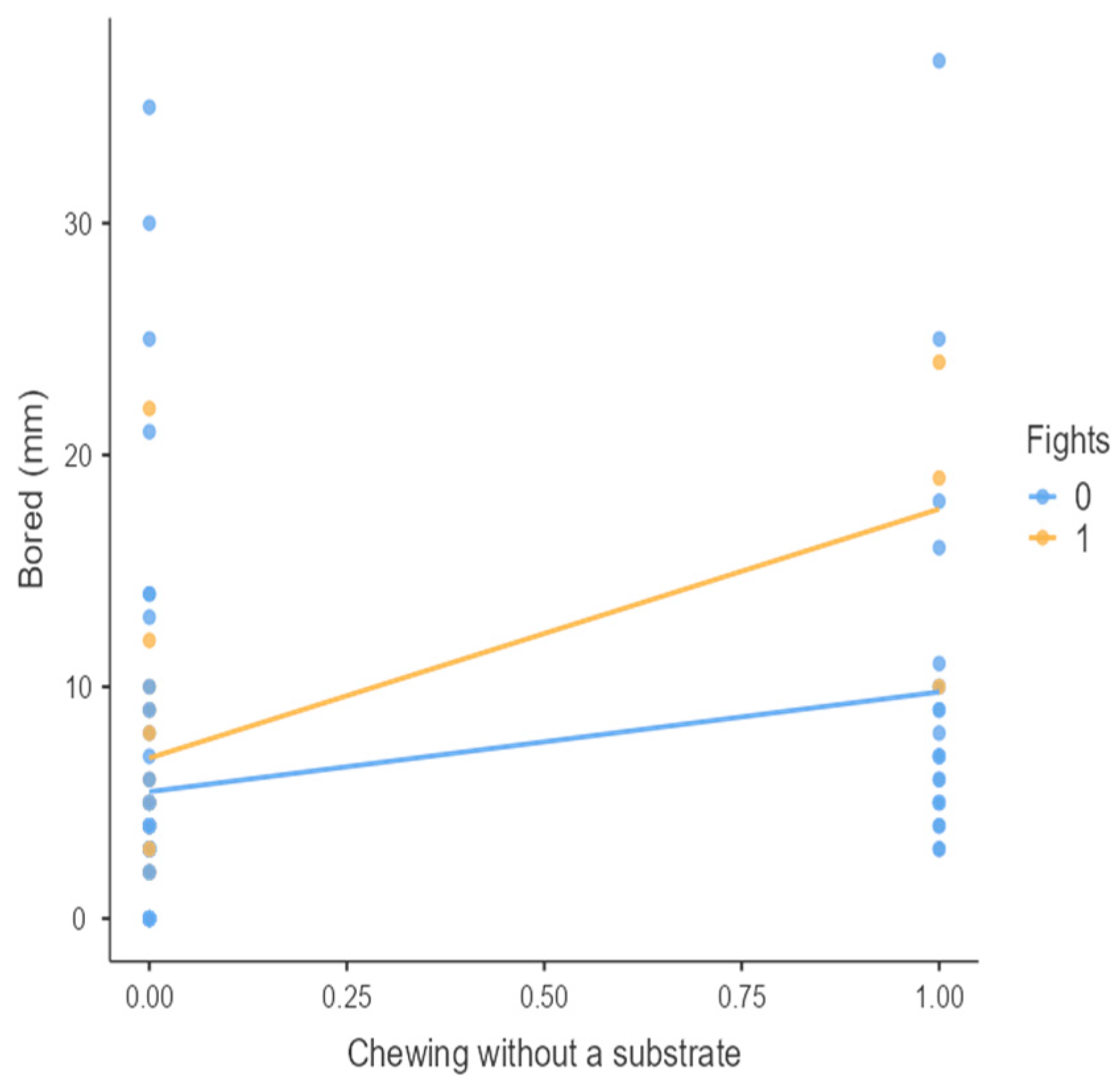

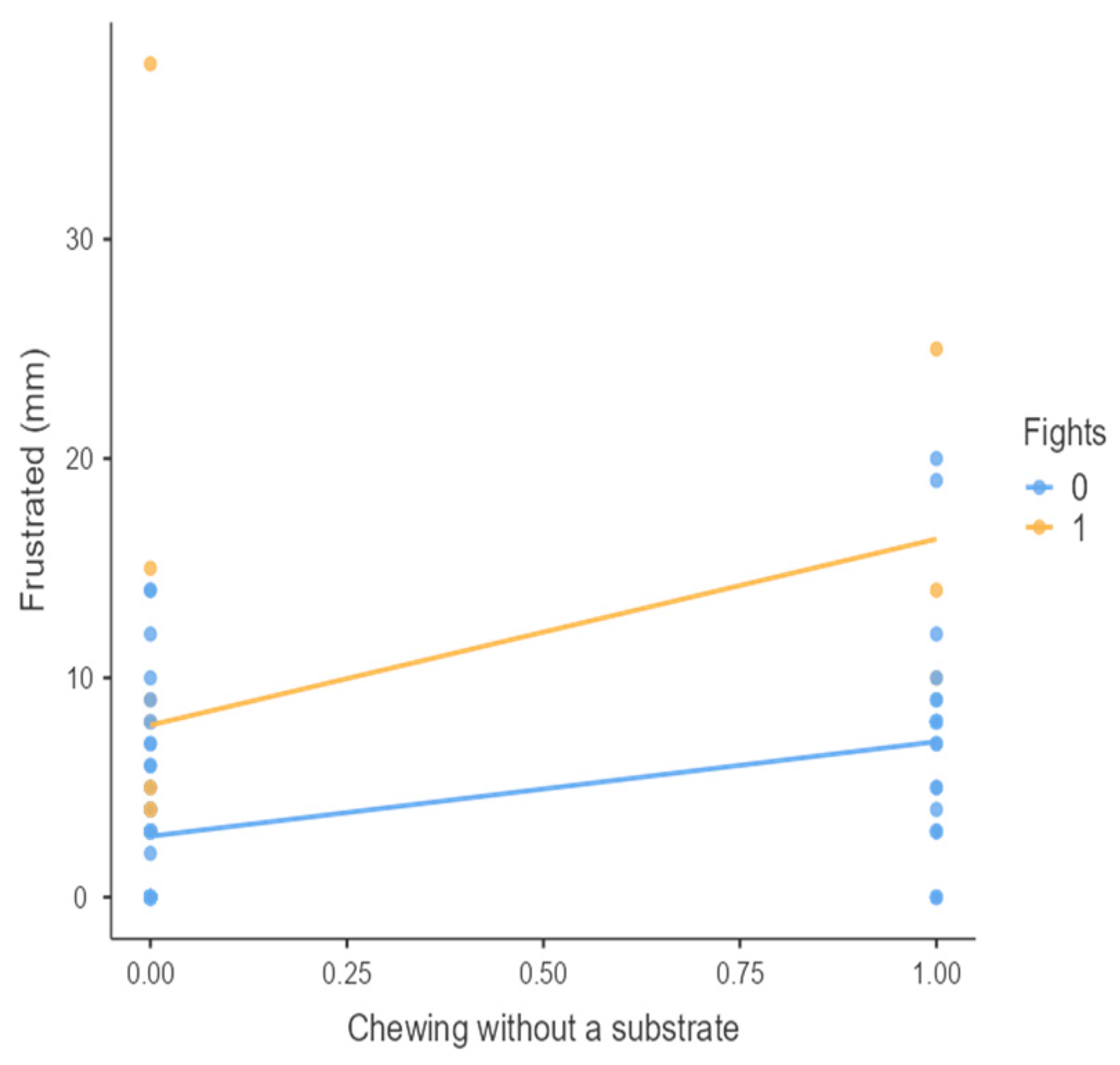

| Fighting | 0.453 *** | 0.121 | 0.178 | 0.412 *** | 0.432 *** | 0.064 | 0.300 ** | −0.221 | 0.426 *** | |

| Ear biting | −0.010 | −0.072 | 0.295 ** | −0.088 | −0.189 | −0.204 | 0.189 | −0.064 | −0.074 | |

| Tail biting | 0.189 | −0.053 | 0.131 | 0.007 | 0.001 | −0.129 | 0.105 | −0.182 | −0.038 | |

| Mounting on the back of other animals | 0.493 *** | −0.027 | 0.201 | 0.601 *** | 0.494 *** | 0.197 | 0.385 *** | 0.191 | 0.567 *** | |

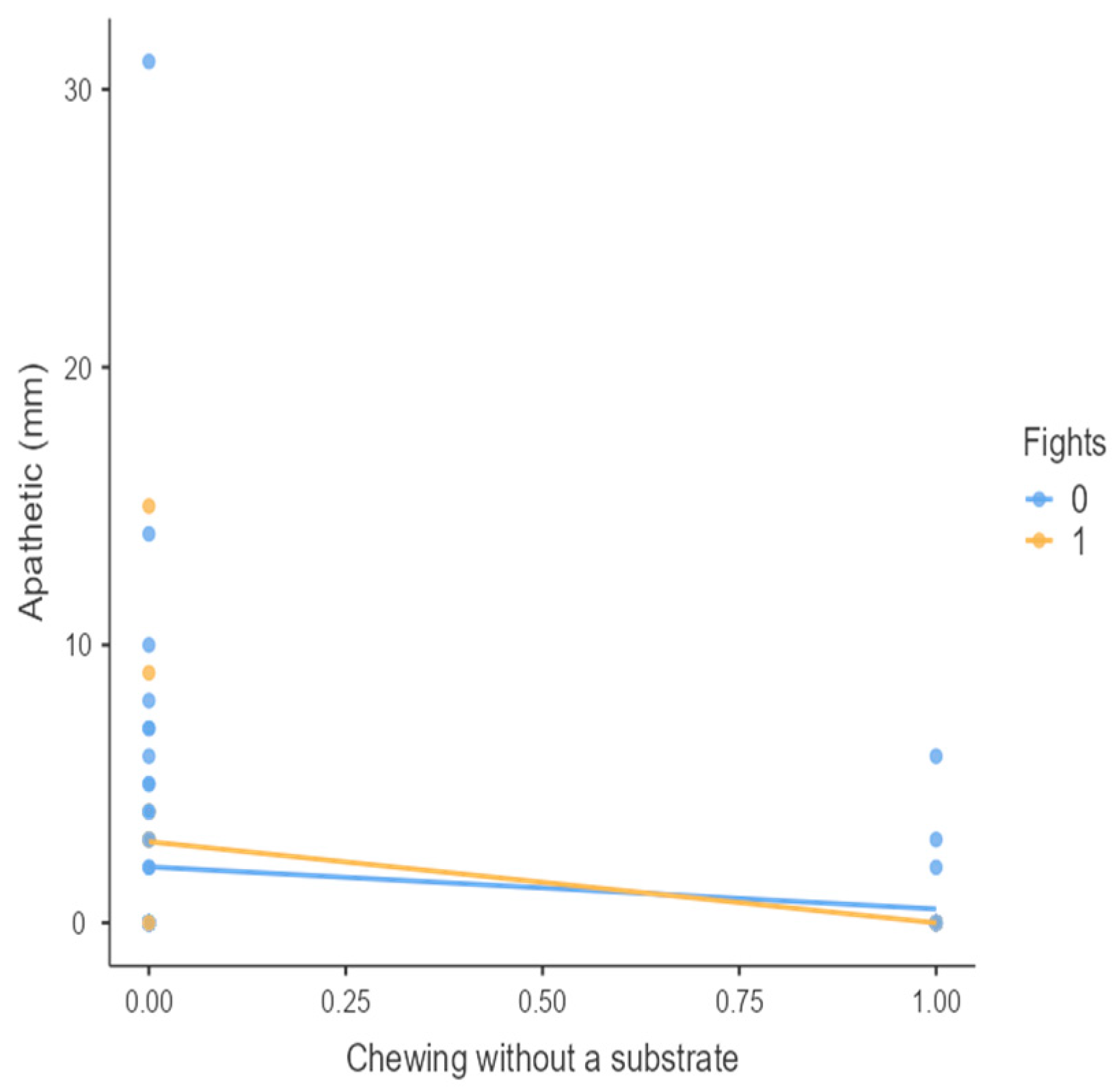

| Chewing without substrate | −0.086 | −0.205 | 0.408 *** | −0.012 | −0.128 | −0.066 | 0.401 *** | −0.048 | −0.128 | |

| Fighting | Score 0 vs. 1 | Mounting the Backs of Other Animals | Score 0 vs. 1 | Chewing Without a Substrate | Score 0 vs. 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional States | χ2 | p | W | χ2 | p | W | χ2 | p | W |

| Active | 4.07 | 0.044 | 2.85 | 5.58 | 0.018 | 3.34 | 2.86 | 0.091 | - |

| Agitated | 18.88 | <0.001 | 6.14 | 22.40 | <0.001 | 6.69 | 0.68 | 0.408 | - |

| Apathetic | 1.36 | 0.244 | - | 0.07 | 0.798 | - | 3.87 | 0.049 | −2.78 |

| Bored | 2.91 | 0.088 | - | 3.71 | 0.054 | - | 15.29 | <0.001 | 5.53 |

| Calm | 12.29 | <0.001 | −4.96 | 21.24 | <0.001 | −6.52 | 1.14 | 0.285 | - |

| Content | 8.78 | 0.003 | −4.19 | 4.39 | 0.036 | −2.96 | 0.38 | 0.538 | - |

| Distressed | 17.14 | <0.001 | 5.85 | 22.50 | <0.001 | 6.71 | 1.50 | 0.221 | - |

| Fearful | 0.13 | 0.716 | - | 2.89 | 0.089 | - | 0.10 | 0.756 | - |

| Friendly | 0.19 | 0.661 | - | 0.17 | 0.682 | - | 3.73 | 0.053 | - |

| Frustrated | 8.26 | 0.004 | 4.06 | 13.62 | <0.001 | 5.22 | 14.81 | <0.001 | 5.44 |

| Happy | 0.39 | 0.534 | - | 0.23 | 0.635 | - | 3.20 | 0.074 | - |

| Indifferent | 4.49 | 0.034 | −3.00 | 3.36 | 0.067 | - | 0.21 | 0.646 | - |

| Inquisitive | 2.84 | 0.092 | - | 0.79 | 0.375 | - | 1.24 | 0.265 | - |

| Irritable | 16.68 | <0.001 | 5.78 | 29.58 | <0.001 | 7.69 | 1.51 | 0.220 | - |

| Lively | 4.15 | 0.042 | 2.88 | 4.94 | 0.026 | 3.14 | 6.55 | 0.011 | −3.62 |

| Playful | 0.03 | 0.871 | - | 0.00 | 0.947 | - | 7.51 | 0.006 | −3.87 |

| Positively occupied | 0.64 | 0.424 | - | 0.20 | 0.653 | - | 1.95 | 0.162 | - |

| Relaxed | 7.64 | 0.006 | −3.91 | 13.43 | <0.001 | −5.18 | 1.17 | 0.280 | - |

| Sociable | 0.43 | 0.514 | - | 0.75 | 0.385 | - | 3.32 | 0.069 | - |

| Tense | 15.64 | <0.001 | 5.59 | 33.27 | <0.001 | 8.16 | 0.00 | 0.911 | - |

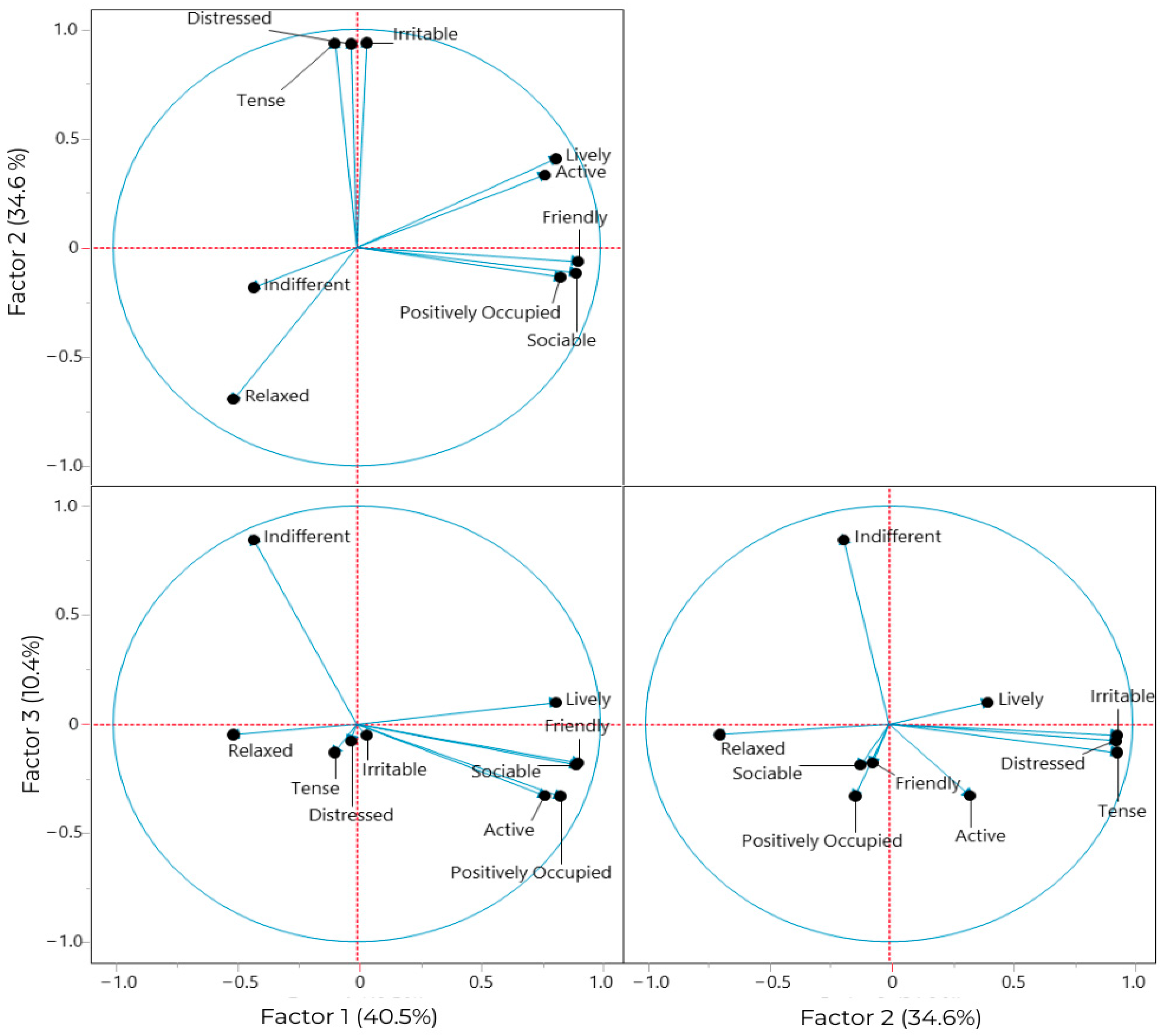

| Variable (Descriptors) | Factor Loadings (FLs) | CM b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 a | PC2 | PC3 | ||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | <0.0001 | |||

| KMO c measure | 0.870 | |||

| Active | 0.772 | 0.332 | −0.328 | 0.81 |

| Distressed | −0.045 | 0.926 | −0.068 | 0.85 |

| Tense | −0.091 | 0.937 | −0.130 | 0.88 |

| Friendly | 0.909 | −0.065 | −0.178 | 0.90 |

| Indifferent | −0.424 | −0.184 | 0.846 | 0.95 |

| Irritable | 0.041 | 0.939 | −0.052 | 0.89 |

| Lively | 0.817 | 0.407 | 0.099 | 0.90 |

| Positively occupied | 0.838 | −0.137 | −0.331 | 0.83 |

| Relaxed | −0.506 | −0.696 | −0.050 | 0.74 |

| Sociable | 0.900 | −0.117 | −0.188 | 0.88 |

| Explained variance (%) | 40.5 | 34.6 | 10.4 | Σ = 85.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mendes, A.; Saraiva, C.; Díez, J.G.; Almeida, M.; Silva, F.; Pires, I.; Saraiva, S. Emotional Welfare and Its Relationship with Social Interactions and Physical Conditions of Finishing Pigs in Lairage at the Slaughterhouse. Animals 2025, 15, 1108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15081108

Mendes A, Saraiva C, Díez JG, Almeida M, Silva F, Pires I, Saraiva S. Emotional Welfare and Its Relationship with Social Interactions and Physical Conditions of Finishing Pigs in Lairage at the Slaughterhouse. Animals. 2025; 15(8):1108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15081108

Chicago/Turabian StyleMendes, Alexandra, C. Saraiva, J. G. Díez, M. Almeida, F. Silva, I. Pires, and Sónia Saraiva. 2025. "Emotional Welfare and Its Relationship with Social Interactions and Physical Conditions of Finishing Pigs in Lairage at the Slaughterhouse" Animals 15, no. 8: 1108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15081108

APA StyleMendes, A., Saraiva, C., Díez, J. G., Almeida, M., Silva, F., Pires, I., & Saraiva, S. (2025). Emotional Welfare and Its Relationship with Social Interactions and Physical Conditions of Finishing Pigs in Lairage at the Slaughterhouse. Animals, 15(8), 1108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15081108