Nursing Behaviour in Alpacas: Parallels in the Andes and Central Europe, and a Rare Allonursing Occurrence

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

2.1.1. The Andes—Ecuador

2.1.2. The Andes—Peru

2.1.3. Central Europe—Poland and Austria

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

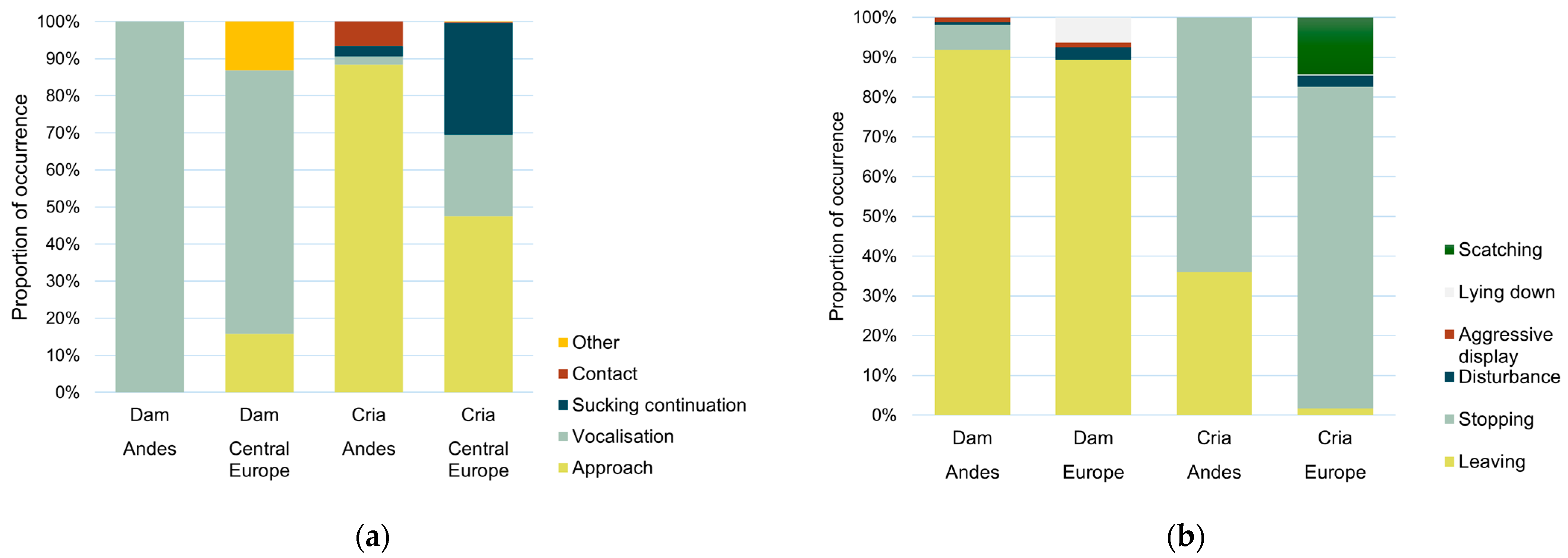

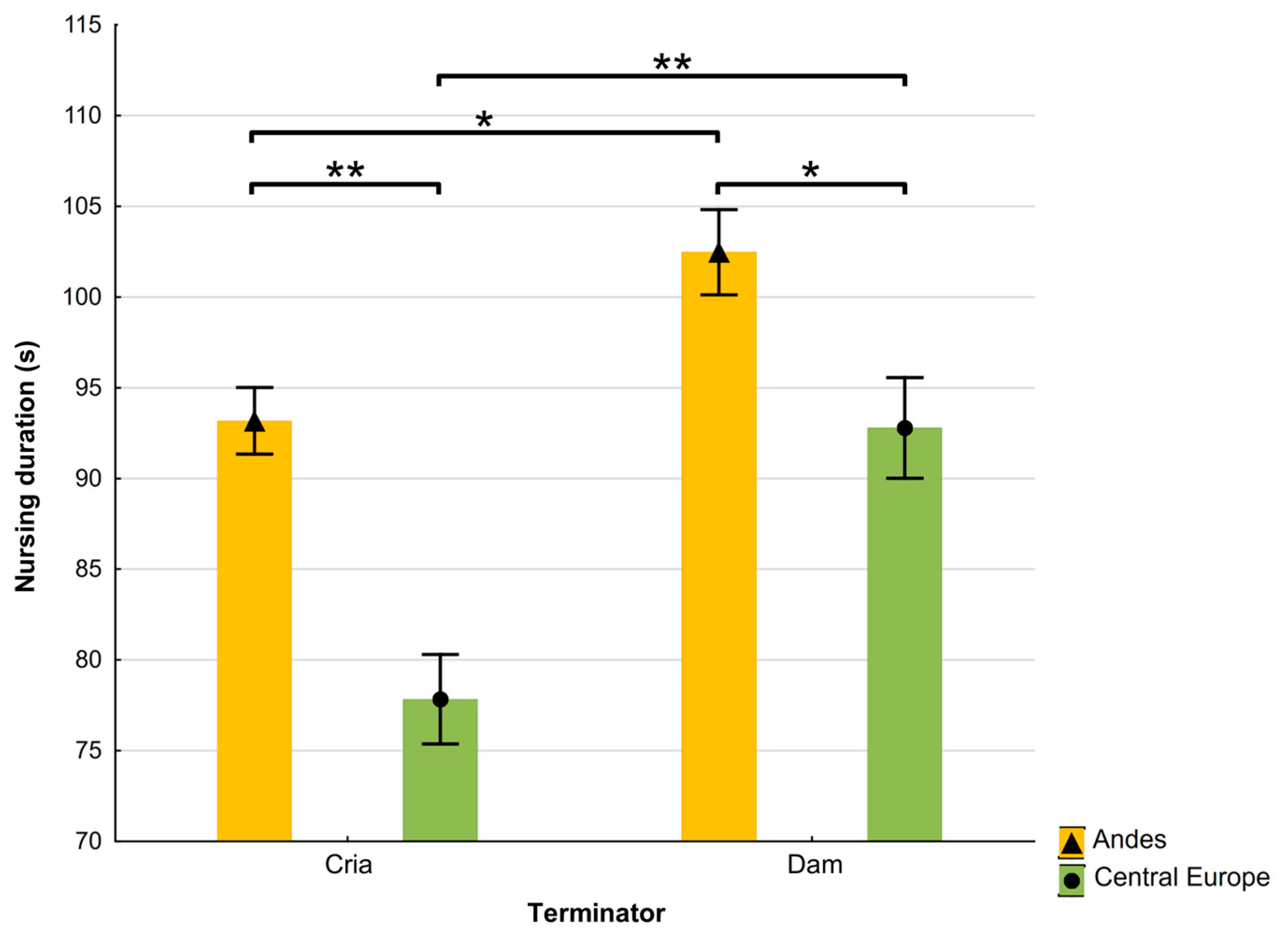

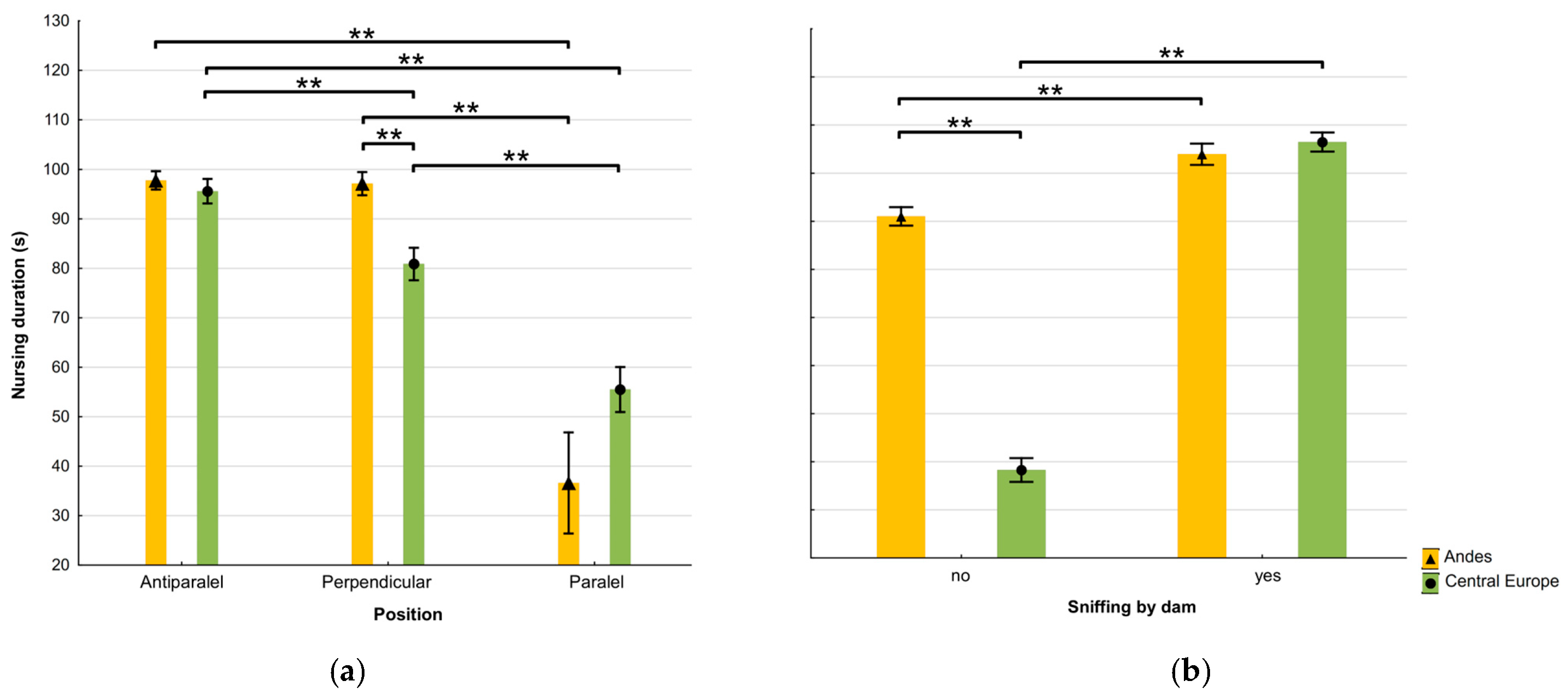

3.1. Nursing Behaviour of Alpacas and Differences Between Locations

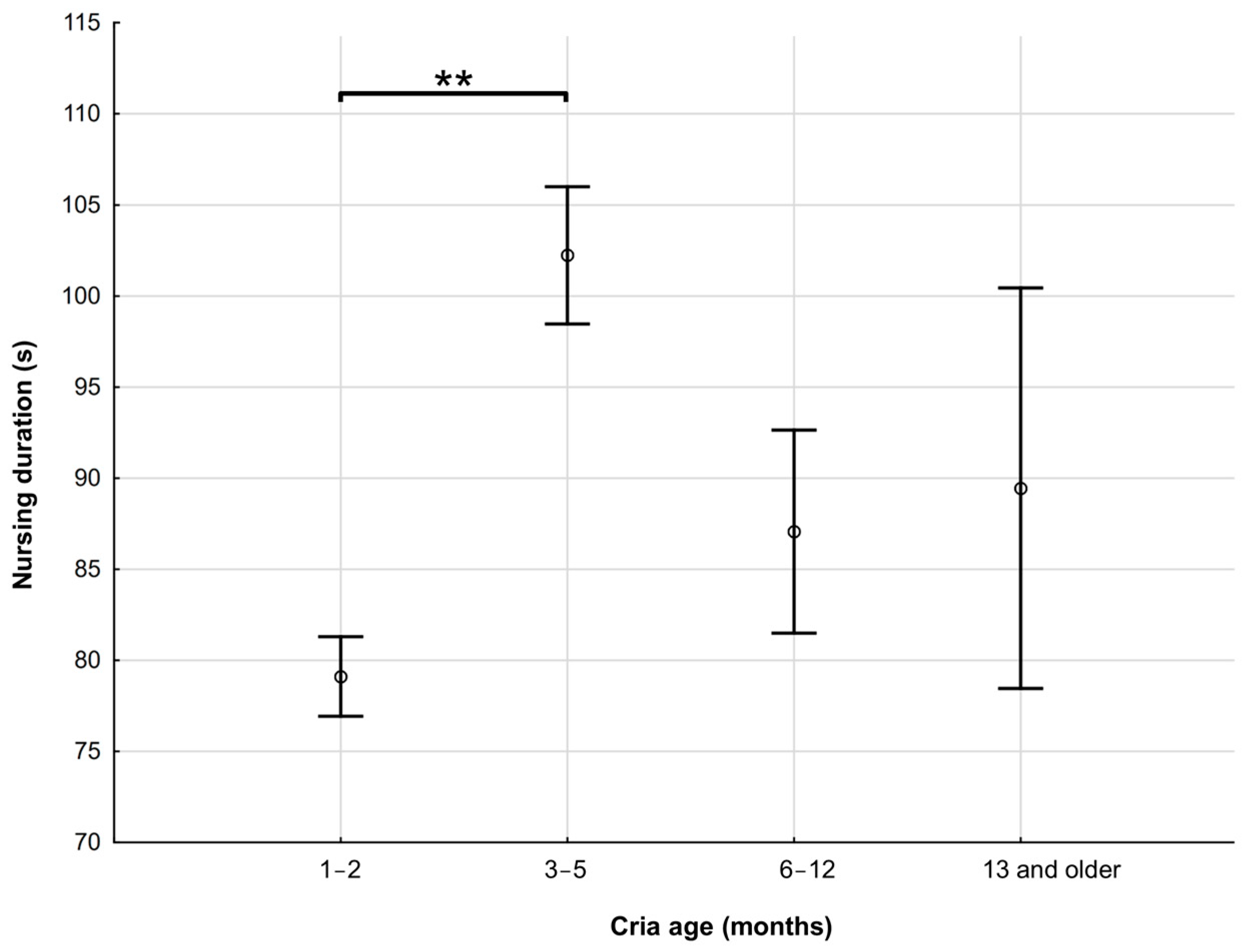

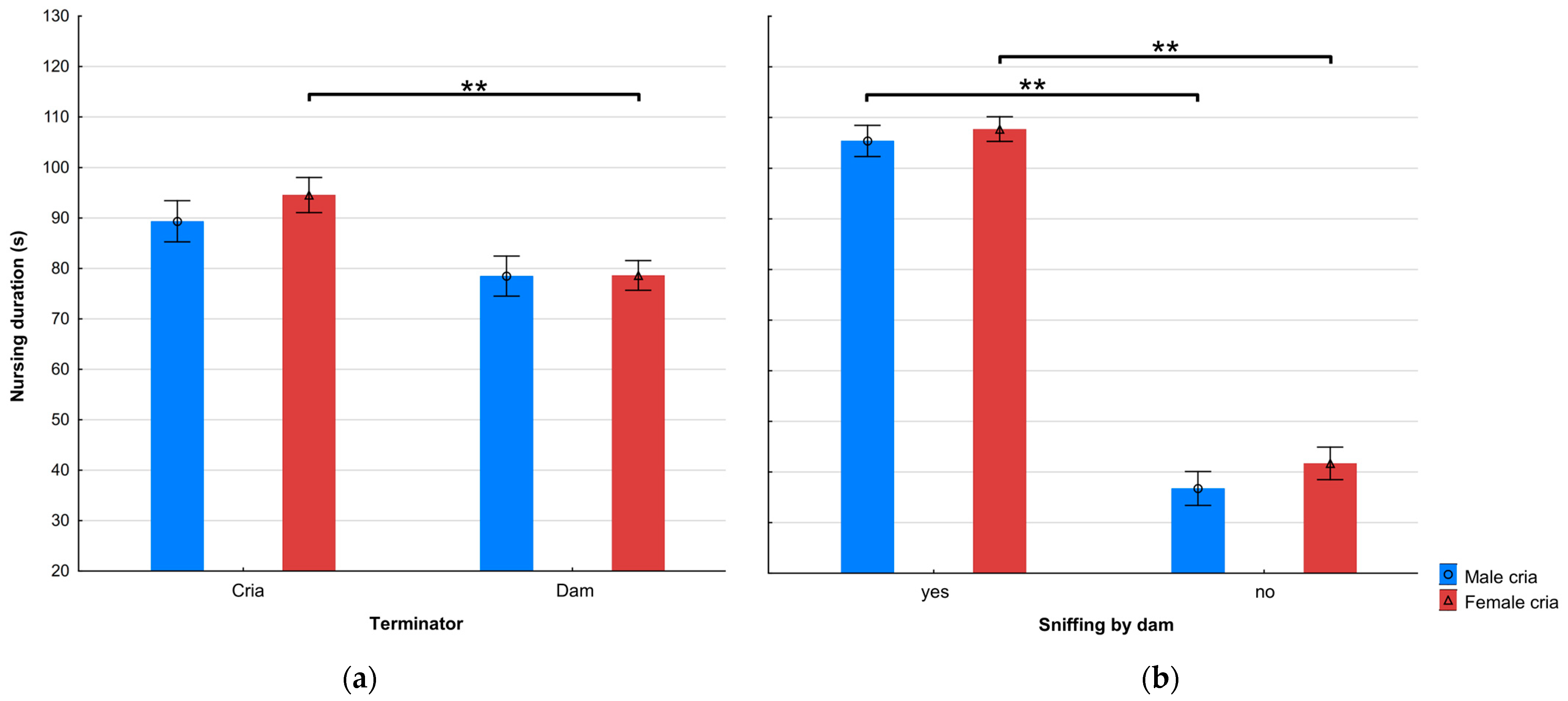

3.2. Effect of Cria Age and Sex

3.3. Occurrence of Allonursing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| GLM | Generalised linear model |

| m a. s. l. | Meters above sea level |

| SACs | South American Camelids |

References

- Miranda-de la Lama, G.C.; Villarroel, M. Behavioural biology of South American domestic camelids: An overview from a welfare perspective. Small Rumin. Res. 2023, 220, 106918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germana Cavero, C.; Chaquilla, O.; Santos, G.; Ferrari, M.; Krusich, C.; Kindgard, F.M. Estudio Socioeconómico de los Pastores Andinos de Perú, Ecuador, Bolivia y Argentina; El Alva: Arequipa, Peru, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT: Crops and Livestock Products. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Gauly, M.; Egen, W.; Trah, M. Zur Haltung von Neuweltkameliden in Mitteleuropa. Tierarztl. Umsch. 1997, 52, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R.; Keeble, E.; Wright, A.; Morgan, K.L. South American camelids in the United Kingdom: Population statistics, mortality rates and causes of death. Vet. Rec. 1998, 142, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubert, S.; von Altrock, A.; Wendt, M.; Wagener, M.G. Llama and Alpaca Management in Germany—Results of an Online Survey among Owners on Farm Structure, Health Problems and Self-Reflection. Animals 2021, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, A.; Blackie, N.; Crilly, J.P.; Reilly, B. Survey of current UK alpaca husbandry practices: Vaccination, treatment and supplementation. Vet. Rec. 2023, 194, e3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, S.J.; Gretgrix, L. Effect of housing conditions on activity and lying behaviour of horses. Animal 2010, 4, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leliveld, L.M.; Riva, E.; Mattachini, G.; Finzi, A.; Lovarelli, D.; Provolo, G. Dairy cow behavior is affected by period, time of day and housing. Animals 2022, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouillon, C.; Erhard, G.; Gauly, M. Suckling Behaviour of Llama (Lama glama). Progress in South American Camelids Research. Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2001, 110, 412–416. [Google Scholar]

- Vaarst, M.; Lund, V.; Roderick, S.; Lockeretz, W. (Eds.) Animal Health and Welfare in Organic Agriculture; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2004; pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ekesbo, I.; Gunnarsson, S. Farm animal Behaviour: Characteristics for Assessment of Health and Welfare, 2nd ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2018; pp. 1–156. [Google Scholar]

- Lévy, F.; Keller, M.; Poindron, P. Olfactory regulation of maternal behavior in mammals. Horm. Behav. 2004, 46, 284–302. [Google Scholar]

- Corona, R.; Lévy, F. Chemical Olfactory Signals and Parenthood in Mammals. Horm. Behav. 2015, 68, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Torriani, M.V.; Vannoni, E.; McElligott, A.G. Mother-young recognition in an ungulate hider species: A unidirectional process. Am. Nat. 2006, 168, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapata, B.; Correa, L.; Soto-Gamboa, M.; Latorre, E.; González, B.A.; Ebensperger, L.A. Allosuckling allows growing offspring to compensate for insufficient maternal milk in farmed guanacos (Lama guanicoe). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 122, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammadi, I.; Chniter, M.; Atigui, M.; Brahmi, M.; Seddik, M.M.; Salem, W.B.; Hammadi, M. Dam parity and calf sex affect maternal and neonatal behaviors during the first week postpartum in stabled Maghrebi dairy camels. Animal 2021, 15, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabek, K.; Swiatek, M.; Micinski, J. Behavioural characteristics of female alpacas and their crias during early rearing. Anim. Sci. Genet. 2024, 20, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okorie, A.U.; Sanda, L.U. Rangeland and Grazing Reserve in Nigeria: Livestock Sub-Sector Review; FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization): Rome, Italy, 1922; Volume 2, pp. 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, M.; Altomonte, I.; da Silva Sant’ana, A.M.; Del Plavignano, G.; Salari, F. Gross, mineral and fatty acid composition of alpaca (Vicugna pacos) milk at 30 and 60 days of lactation. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 132, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibary, A.; Johnson, L.W.; Pearson, L.K.; Rodriguez, J.S. Lactation and neonatal care. In Llama and Alpaca Care: Medicine, Surgery, Reproduction, Nutrition, and Herd Health; Cebra, C., Anderson, D.E., Tibary, A., Van Saun, R.J., Johnson, L.W., Eds.; Elsevier Health Sciences: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013; pp. 286–297. [Google Scholar]

- Lidfors, L.M.; Jensen, P.; Algers, B. Suckling in free-ranging beef cattle—Temporal patterning of suckling bouts and effects of age and sex. Ethology 1994, 98, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Miranda, C.R.; Thompson, K.V.; Callard, M. Suckling behavior in domestic goats: Interaction between litter size and kid sex. Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 1998, 11, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejcmanová, P.; Vymyslická, P.; Koláčková, K.; Antonínová, M.; Havlíková, B.; Stejskalová, M.; Policht, R.; Hejcman, M. Suckling behavior of eland antelopes (Taurotragus spp.) under semi-captive and farm conditions. J. Ethol. 2011, 29, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Weary, D.M. Maternal Behavior in Cattle. Horm. Behav. 2007, 52, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J.A.; Crowell-Davis, S.L. Maternal behavior of Belgian (Equus caballus) mares. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1994, 41, 161–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell-Davis, S.L. Nursing behaviour and maternal aggression among Welsh ponies (Equus caballus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1985, 14, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Brandlová, K.; Bartoš, L.; Haberová, T. Camel Calves as Opportunistic Milk Thefts? The First Description of Allosuckling in Domestic Bactrian Camel (Camelus bactrianus). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53052. [Google Scholar]

- Komárková, M.; Bartošová, J. Lateralized suckling in domestic horses (Equus caballus). Anim. Cogn. 2013, 16, 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Waltl, B.; Appleby, M.C.; Sölkner, J. Effects of relatedness on the suckling behaviour of calves in a herd of beef cattle rearing twins. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1995, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Packer, C.; Lewis, S.; Pusey, A. A comparative analysis of nonoffspring nursing. Anim. Behav. 1992, 43, 265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Gloneková, M.; Brandlová, K.; Pluháček, J. Stealing Milk by Young and Reciprocal Mothers: High Incidence of Allonursing in Giraffes, Giraffa camelopardalis. Anim. Behav. 2016, 113, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Villagran, M.; De La Fuente, L.; Ungerfeld, R. Pampas deer fawns (Ozotoceros bezoarticus, Linnaeus, 1758) feeding time budget during the first twelve weeks of life. North-West J. Zool. 2012, 8, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wronski, T.; Apio, A.; Wanker, R.; Plath, M. Behavioural repertoire of the bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus): Agonistic interactions, mating behaviour and parent–offspring relations. J. Ethol. 2006, 24, 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Aba, M.A.; Bianchi, C.; Cavilla, V. South American Camelids. In Behavior of Exotic Pets; Tynes, V.V., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, D.; Barrette, C. Suckling and Weaning in Captive White-Tailed and Fallow Deer. Behaviour 1985, 94, 128–149. [Google Scholar]

- García y González, E.G.; Flores, J.A.; Delgadillo, J.A.; González-Quirino, T.; Fernández, I.G.; Terrazas, A.; Hernández, H. Early nursing behaviour in ungulate mothers with hider offspring (Capra hircus): Correlations between milk yield and kid weight. Small Rumin. Res. 2017, 151, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kour, H.; Corbet, N.J.; Patison, K.P.; Swain, D.L. Changes in the suckling behaviour of beef calves at 1 month and 4 months of age and effect on cow production variables. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 236, 105219. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, L.; McGowan, M.R.; Johnston, S.D.; Lisle, A.T.; Schooley, K. Suckling behaviour of beef calves during the first five days postpartum. Ruminants 2022, 2, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloneková, M.; Vymyslická, P.J.; Žáčková, M.; Brandlová, K. Giraffe Nursing Behaviour Reflects Environmental Conditions. Behaviour 2017, 154, 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Gloneková, M.; Brandlová, K.; Pluháček, J. Further Behavioural Parameters Support Reciprocity and Milk Theft as Explanations for Giraffe Allonursing. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7024. [Google Scholar]

- Gloneková, M.; Brandlová, K.; Pluháček, J. Giraffe Males Have Longer Suckling Bouts than Females. J. Mammal. 2020, 101, 558–563. [Google Scholar]

- Drábková, J.; Bartošová, J.; Bartoš, L.; Kotrba, R.; Pluháček, J.; Švecová, L.; Dušek, A.; Kott, T. Sucking and allosucking duration in farmed red deer (Cervus elaphus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 113, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, E.Z.; Linklater, W.L.; Stafford, K.J.; Minot, E.O. Aging and improving reproductive success in horses: Declining residual reproductive value or just older and wiser? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2000, 47, 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Pluháček, J.; Bartošová, J.; Bartoš, L. Suckling behavior in captive plains zebra (Equus burchellii): Sex differences in foal behavior. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Elmi, A.A. Camel Husbandry and Management by Ceeldheer Pastoralists in Central Somalia; Agricultural Administration Unit, Overseas Development Institute: Mogadishu, Somalia, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Marcet-Rius, M.; Freitas-de-Melo, A.; Muns, R.; Mora-Medina, P.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Orihuela, A. Allonursing in Wild and Farm Animals: Biological and Physiological Foundations and Explanatory Hypotheses. Animals 2021, 11, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Rodríguez, J.; Palacio, J.; Casasús, I.; Revilla, R.; Sanz, A. Performance and nursing behaviour of beef cows with different types of calf management. Animal 2009, 3, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thodberg, K.; Jensen, K.H.; Herskin, M.S. Nursing behaviour, postpartum activity and reactivity in sows: Effects of farrowing environment, previous experience and temperament. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 77, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanheukelom, V.; Driessen, B.; Geers, R. The effects of environmental enrichment on the behaviour of suckling piglets and lactating sows: A review. Livest. Sci. 2012, 143, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, J.F.; Côté, S.D.; Festa-Bianchet, M.; Ouellet, J.P. Maternal care in white-tailed deer: Trade-off between maintenance and reproduction under food restriction. Anim. Behav. 2008, 75, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, B.A.; Palma, R.E.; Zapata, B.; Marín, J.C. Taxonomic and biogeographical status of guanaco Lama guanicoe (Artiodactyla, Camelidae). Mamm. Rev. 2006, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulin, A. Why do lactating females nurse alien offspring? A review of hypotheses and empirical evidence. Anim. Behav. 2002, 63, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landete-Castillejos, T.; Garcia, A.; Garde, A.; Gallego, L. Milk intake and production curves and allosuckling in captive Iberian red deer, Cervus elaphus hispanicus. Anim. Behav. 2000, 60, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, S.C.; Weladji, R.B.; Holand, Ø.; de Rioja, C.M.; Ehmann, R.K.; Nieminen, M. Allosuckling in Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus): Milk-theft, Mismothering or Kin Selection? Behav. Process. 2014, 107, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, K.J.; Lukas, D. Revisiting non-offspring nursing: Allonursing evolves when the costs are low. Biol. Lett. 2014, 10, 20140378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, B.; Gonzalez, B.A.; Ebensperger, L.A. Allonursing in captive guanacos, Lama guanicoe: Milk theft or misdirected parental care? Ethology 2009, 115, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orihuela, A.; Bienboire-Frosini, C.; Chay-Canul, A.; Álvarez-Macías, A.; Marcet-Rius, M.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Mota-Rojas, D. Allonursing in water buffalo: Cooperative maternal behavior in domestic Bovidae. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2024, 12, 2024023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekvall, K. Effects of social organization, age and aggressive behaviour on allosuckling in wild fallow deer. Anim. Behav. 1998, 56, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pélabon, C.; Yoccoz, N.G.; Ropert-Coudert, Y.; Caron, M.; Peirera, V. Suckling and Allosuckling in Captive Fallow Deer (Dama dama, Cervidae). Ethology 1998, 104, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fiallos, L.; Herrera, R.S.; Velázquez, R. Flora diversity in the Ecuadorian Páramo grassland ecosystem. Cuban J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 49, 399–405. [Google Scholar]

- La Frenierre, J.; Mark, B.G. Detecting Patterns of Climate Change at Volcán Chimborazo, Ecuador, by Integrating Instrumental Data, Public Observations, and Glacier Change Analysis. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 979–997. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro, B.; Zuňiga, S.; Zeballos, H. Climatología de la Reserva Nacional Salinas y Aguada Blanca, suroeste del Perú. In Diversidad Biológica de la Reserva Nacional de Salinas y Aguada Blanca; Zeballos, H., Zeballos, H., Ochoa, J.A., Lopez, E., Eds.; Litho & Arte SAC: Lima, Peru, 2010; pp. 261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Catorci, A.; Cesaretti, S.; Velasquez, J.L.; Malatesta, L.; Zeballos, H. The interplay of land forms and disturbance intensity drive the floristic and functional changes in the dry Puna pastoral systems (southern Peruvian Andes). Plant Biosyst.-Int. J. Plant Biol. 2014, 148, 547–557. [Google Scholar]

- Climate-Data. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Šandlová, K.; Komárková, M.; Ceacero, F. Daddy, daddy cool: Stallion–foal relationships in a socially-natural herd of Exmoor ponies. Anim. Cogn. 2020, 23, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pilarczyk, B.; Pilarczyk, R.; Sablik, P. The impact of breeding and farming conditions on the welfare of alpacas (Vicugna pacos). Acta Sci. Pol. Zootech. 2023, 22, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Passillé, A.M.; Rabeyrin, M.; Rushen, J. Associations between milk intake and activity in the first days of a calf’s life and later growth and health. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 175, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Marcet-Rius, M.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Lezama-García, K.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Bienboire-Frosini, C. The role of oxytocin in domestic animal’s maternal care: Parturition, bonding, and lactation. Animals 2023, 13, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, F.C.; Farfan, R.D. Dry Season Forage Selection by Alpaca (Lama pacos) in Southern Peru. J. Range. Manag. 1984, 37, 330–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, F.C.; Florez, A.; Pfister, J. Sheep and Alpaca Productivity on High Andean Rangelands in Peru. J. Anim. Sci. 1989, 67, 3087–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker, W.I.A.; El-Zubeir, I.E.M. Impact of husbandry, stages of lactation and parity number on milk yield and chemical composition of dromedary camel milk. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2014, 26, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weary, D.M.; Jasper, J.; Hötzel, M.J. Understanding weaning distress. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 110, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abecia, D.A.; Canudo, C.; Palacios, C.; Canto, F. Measuring lamb activity during lactation by actigraphy. Chronobiol. Int. 2022, 39, 1368–1380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stěhulová, I.; Špinka, M.; Šárová, R.; Máchová, L.; Kněz, R.; Firla, P. Maternal behaviour in beef cows is individually consistent and sensitive to cow body condition, calf sex and weight. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 144, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marešová, J.; Kokošková, T.; Fedorova, T. Husbandry and breeding practices of South American camelids in Ecuador and Peru, and the impact of country, gender, and farming experience thereon. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2025, submitted.

- Coulon, M.; Baudoin, C.; Heyman, Y.; Deputte, B.L. Cattle discriminate between familiar and unfamiliar conspecifics by using only head visual cues. Anim. Cogn. 2011, 14, 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Murphey, R.M.; Paranhos da Costa, M.J.R.; Gomes da Silva, R.; de Souza, R. Allonursing in river buffalo, Bubalis bubalis: Nepotism, incompetence, or thievery? Anim. Behav. 1995, 49, 1611–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B.W. A review on reproduction in South American camelids. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2000, 58, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Idani, G. Suckling and Allosuckling Behavior in Wild Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis tippelskirchi). Mamm. Biol. 2018, 93, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, T. The Evaluation of Reproduction in Bactrian Camels (Camelus bactrianus) and the Possibilities of Using Non-invasive Methods for Detection of Heat and Pregnancy. Ph.D. Thesis, Czech University of Life Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, P.R.; Roca Fraga, F.J.; Blumer, S.; Thompson, A.N. Triplet lambs and their dams—A review of current knowledge and management systems. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2019, 62, 399–437. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoš, L.; Vaňková, D.; Hyánek, J.; Šiler, J. Impact of allosucking on growth of farmed red deer calves (Cervus elaphus). Anim. Sci. 2001, 72, 493–500. [Google Scholar]

- Víchová, J.; Bartoš, L. Allosuckling in cattle: Gain or compensation? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 94, 223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Haberová, T.; Fedorov, P. Umělý odchov velblouda dvouhrbého (Camelus bactrianus)—Hand-rearing of Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus). Gazella 2012, 39, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

| Behaviour | Definition |

|---|---|

| Way of nursing initiation | |

| Approach | Animal approach by walk or run |

| Contact | Animal performed any physical contact with the second animal before nursing, mostly touching by nose or jumping on dam |

| Suckling continuation | Situation when cria terminated sucking and started a new bout longer than 10 s after, without any contact or interaction with dam |

| Vocalisation | Any sound produced before nursing |

| Other | Mostly standing up or following the second animal that participated in nursing |

| Sniffing behaviour during nursing | |

| Sniffing by the dam | Dam sniffs the cria’s body |

| Way of nursing termination | |

| Stopping | Animal terminated the nursing/sucking without firm movement or interaction |

| Aggressive display | Kicking, spitting, or pushing away |

| Scratching | Animal started to scratch instead of nursing/sucking |

| Lying down | Animal lay down on the ground |

| Disturbance | Animals were disturbed by an external factor |

| Number of Nursing Bouts | Mean ± SE Nursing Duration (s) | Median Nursing Duration (s) | SD | Minimum Nursing Duration (s) | Maximum Nursing Duration (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andes | 925 | 96.96 ± 1.46 | 97 | 44.29 | 9 | 424 |

| Central Europe | 974 | 85.04 ± 1.87 | 87 | 58.26 | 5 | 300 |

| Effect | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | 1 | 1.02 | n. s. |

| Position of cria | 2 | 7.01 | p < 0.001 |

| Terminator | 1 | 19.69 | p < 0.001 |

| Sniffing by dam | 1 | 107.17 | p < 0.001 |

| Location × Position of cria | 2 | 6.78 | p < 0.05 |

| Location × Terminator | 1 | 5.00 | p < 0.05 |

| Position of cria × Terminator | 2 | 0.71 | n. s. |

| Location × Sniffing by dam | 1 | 149.57 | p < 0.001 |

| Position of cria × Sniffing by dam | 2 | 2.12 | n. s. |

| Terminator × Sniffing by dam | 1 | 2.22 | n. s. |

| Effect | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing dam (random effect) | 23 | 3.06 | p < 0.001 |

| Cria age (days) | 1 | 1.26 | n. s. |

| Position × Cria sex | 4 | 0.69 | n. s. |

| Terminator × Cria sex | 2 | 11.29 | p < 0.001 |

| Sniffing by dam × Cria sex | 2 | 119.53 | p < 0.001 |

| Position × Cria age (days) | 2 | 1.97 | n. s. |

| Terminator × Cria age (days) | 1 | 0.01 | n. s. |

| Sniffing by dam × Cria age (days) | 1 | 0.23 | n. s. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marešová, J.; Kokošková, T.; Tichá, E.; Fedorova, T. Nursing Behaviour in Alpacas: Parallels in the Andes and Central Europe, and a Rare Allonursing Occurrence. Animals 2025, 15, 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15070916

Marešová J, Kokošková T, Tichá E, Fedorova T. Nursing Behaviour in Alpacas: Parallels in the Andes and Central Europe, and a Rare Allonursing Occurrence. Animals. 2025; 15(7):916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15070916

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarešová, Jana, Tersia Kokošková, Eliška Tichá, and Tamara Fedorova. 2025. "Nursing Behaviour in Alpacas: Parallels in the Andes and Central Europe, and a Rare Allonursing Occurrence" Animals 15, no. 7: 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15070916

APA StyleMarešová, J., Kokošková, T., Tichá, E., & Fedorova, T. (2025). Nursing Behaviour in Alpacas: Parallels in the Andes and Central Europe, and a Rare Allonursing Occurrence. Animals, 15(7), 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15070916