A Novel Approach to Engaging Communities Through the Use of Human Behaviour Change Models to Improve Companion Animal Welfare and Reduce Relinquishment

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the challenges to pet welfare within the target community?

- (2)

- What are the pet-related support needs of pet owners in the target community?

- (3)

- Investigate a co-creation approach to the design of support services to help pet owners within the target community to positively care for their pets.

2. Design Process

- Access the most vulnerable pets and their owners at the right time.

- Positively impact the welfare of as many pets as possible within the community.

- Work towards a sustained change to pet owner behaviour to make appropriate decisions and provide a good quality of life for their pets with frontline support from within the community enabled by Woodgreen.

2.1. Understand the Community

2.1.1. Desk-Based Research

- (1)

- Team member experiences of working within the target community including the pet welfare challenges encountered;

- (2)

- The pet-related needs of the community;

- (3)

- Views of wider pet-related issues.

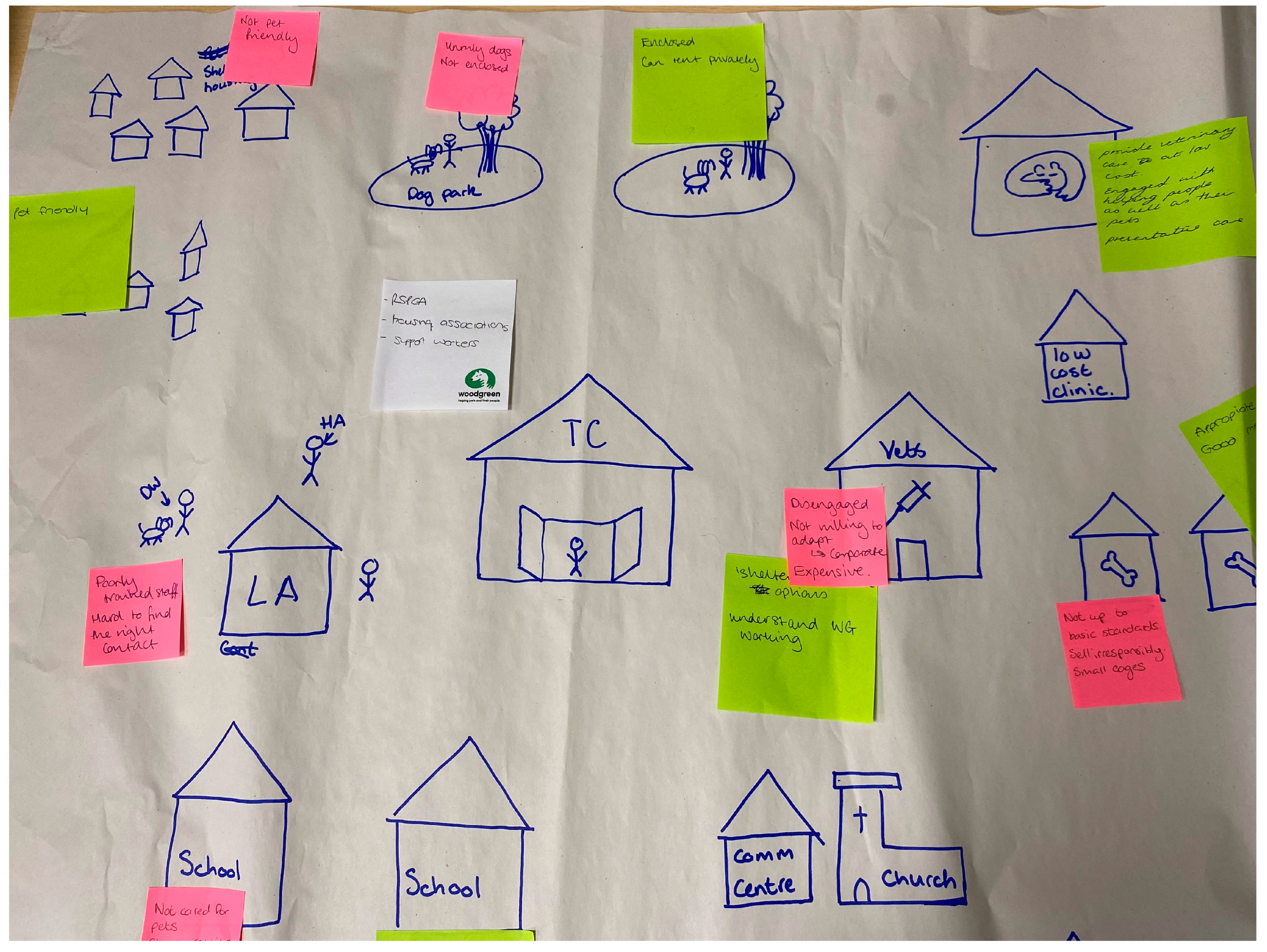

2.1.2. Mapping

2.1.3. Community-Based Research

- (1)

- Which types of pets are owned within the target community?

- (2)

- Where do pet owners seek advice related to their pets?

- (3)

- What is the awareness of Woodgreen and pet-related support service provision within the area?

- (4)

- What factors influence owners’ provision of veterinary care for their pets?

- (5)

- What are the broader animal welfare issues within the target community?

2.1.4. Community Research Findings

- The importance (and challenges) of community

- Decision making and action planning

“Now the problem is if there was something wrong with Fred, to get him [sic] would be a problem because you can’t pick him up. I like my skin on my body and he’s a big strong cat.”(Participant 1)

- Views of charity

“I think my assumption has always been that that’s (charitable services) for people who couldn’t… who either are like I need to solve this problem, or I’ll give up my dog, or who really can’t afford to go elsewhere […].”(Participant 2)

- Well meaning but misguided

“I’ve got one example of a lady who we’re working with at the moment, and she’s already got 2 cats and she’s gone and got another one, but she can’t really… She can’t afford the third one, but she couldn’t resist it.”(Participant 6)

“People who’ve got the pets have got them because they want them, because they think a lot about them, want care for them.”(Participant 6)

2.2. Application of Human Behaviour Change Models

- How much of an impact changing the behaviour will have on the desired outcome;

- How likely it is that the behaviour can be changed;

- How likely it is that the behaviour will have a positive or negative impact on other related behaviours;

- How easy it will be to measure the behaviour

2.2.1. Intervention Development

- Pre-contemplation—During this stage, individuals are unaware of the need to change and have no current intention to do so.

- Contemplation—At this stage, individuals are aware of a problem and begin to consider actions to remedy it.

- Preparation—Individuals in this stage are intending to take action in the near future and take steps to prepare to do so.

- Action—At this stage, individuals undertake an action to change their behaviour.

- Maintenance—During the maintenance stage, individuals have to work to prevent relapse and maintain the behaviour.

2.2.2. Action Planning—Implementation Intentions

What do I need to do…Register my dog with a vetWhy do I need to do it…So that if they are ill I am able to take them quicklyHow do I need to do it…I need to phone the vet on this number…When will I do it…Tomorrow morning after I have dropped the children at schoolWho will help me to do it…I am able to do this myself

2.3. Co-Creation with the Community

“I only take animals to the vet when it’s a problem… I always try to treat at home first and then take them to the vet if it doesn’t work. Because of money, because of insurance.”

“I’ve got five animals and if I take them to the vet every time they need a vet I’d be skint.”

“To actually physically get some of the cats to the vet would cause me problems.”

“I didn’t know that you did all the neutering and that last year, so there’s obviously a lack of getting out to the general public.”

3. Discussion

Limitations and Further Considerations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HBCL | Human Behaviour Change for Life |

| HBC | human behaviour change |

| SoC | Stages of Change |

| BCW | Behaviour Change Wheel |

References

- UK Pet Food. Paw-Some New Pet Population Data Released by UK Pet Food 2024. Available online: https://www.ukpetfood.org/resource/paw-some-new-pet-population-data-released-by-uk-pet-food.html (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Meyer, I.; Forkman, B.; Fredholm, M.; Glanville, C.; Guldbrandtsen, B.; Ruiz Izaguirre, E.; Palmer, C.; Sandøe, P. Pampered pets or poor bastards? The welfare of dogs kept as companion animals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 251, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuz Beneitez, M.J.; María, G.A. Public Opinion About Punishment for Animal Abuse in Spain: Animal Attributes as Predictors of Attitudes Toward Penalties. Anthrozoos 2022, 35, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, K.E.; Mead, R.; Casey, R.A.; Upjohn, M.M.; Christley, R.M. Why Do People Want Dogs? A Mixed-Methods Study of Motivations for Dog Acquisition in the United Kingdom. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 877950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioja-Lang, F.; Bacon, H.; Connor, M.; Dwyer, C.M. Prioritisation of animal welfare issues in the UK using expert consensus. Vet. Rec. 2020, 187, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.; Yates, D.; Dean, R.; Stavisky, J. A novel approach to welfare interventions in problem multi-cat households. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioja-Lang, F.; Bacon, H.; Connor, M.; Dwyer, C.M. Determining priority welfare issues for cats in the United Kingdom using expert consensus. Vet. Rec. Open 2019, 6, e000365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDSA. PDSA Animal Wellbeing Report 2022. Available online: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/media/12965/pdsa-paw-report-2022.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Rioja-Lang, F.; Bacon, H.; Connor, M.; Dwyer, C.M. Rabbit welfare: Determining priority welfare issues for pet rabbits using a modified Delphi method. Vet. Rec. Open 2019, 6, e000363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, S.M.; Hupe, T.; Morris, K.N. Punishment to support: The need to align animal control enforcement with the human social justice movement. Animals 2020, 10, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Dogs and Cats Homes. ADCH Annual Return Summary Data-2023. Available online: https://adch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/ADCH-Annual-Return-Summary-data-2023-1.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Hobson, S.J.; Bateman, S.; Coe, J.B.; Oblak, M.; Veit, L. The impact of deferred intake as part of Capacity for Care (C4C) on shelter cat outcomes. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2023, 26, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.B.H.; Sandøe, P.; Nielsen, S.S. Owner-related reasons matter more than behavioural problems—A study of why owners relinquished dogs and cats to a danish animal shelter from 1996 to 2017. Animals 2020, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowall, S.; Hazel, S.J.; Hamilton-Bruce, M.A.; Stuckey, R.; Howell, T.J. Association of Socioeconomic Status and Reasons for Companion Animal Relinquishment. Animals 2024, 14, 2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, G.A.; Torjussen, A.; Reeve, C. Companion animal adoption and relinquishment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Households with children at greatest risk of relinquishing a cat or dog. Anim. Welf. 2023, 32, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesel, G.; Brodbelt, D.; Pfeiffer, D.U. Characteristics of relinquished dogs and their owners at 14 rehoming centers in the United Kingdom. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2010, 13, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, E.; Slater, M.; Garrison, L.; Drain, N.; Dolan, E.; Scarlett, J.M.; Zawistowski, S.L. Large dog relinquishment to two municipal facilities in New York city and Washington, D.C.: Identifying targets for intervention. Animals 2014, 4, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazel, S.J.; Jenvey, C.J.; Tuke, J. Online relinquishments of dogs and cats in Australia. Animals 2018, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, V.; Hinde, K.; Line, E.; Todd, R.; Saunders, R.A. Rabbit relinquishment through online classified advertisements in the United Kingdom: When, why, and how many? J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2019, 22, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavisky, J.; Brennan, M.L.; Downes, M.J.; Dean, R.S. Opinions of UK Rescue Shelter and Rehoming Center Workers on the Problems Facing Their Industry. Anthrozoos 2017, 30, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.D.; Mills, D.S. The effect of the kennel environment on canine welfare: A critical review of experimental studies. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, C.L.; Grandin, T.; Enns, R.M. Human interaction and cortisol: Can human contact reduce stress for shelter dogs? Physiol. Behav. 2006, 87, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, C.L.; Enns, R.M.; Grandin, T. Noise in the animal shelter environment: Building design and the effects of daily noise exposure. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2006, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, A.C.; Vitale, K.R.; Udell, M.A.R. The effect of owner presence and scent on stress resilience in cats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 243, 105444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimarelli, G.; Schindlbauer, J.; Pegger, T.; Wesian, V.; Viranyi, Z. Secure base effect in former shelter dogs and other family dogs: Strangers do not provide security in a problem-solving task. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, E.D.; Weiss, E.; Slater, M.R. Welfare Impacts of Spay/Neuter-Focused Outreach on Companion Animals in New York City Public Housing. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2017, 20, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, E.D.; Scotto, J.; Slater, M.; Weiss, E. Risk factors for dog relinquishment to a Los Angeles municipal animal shelter. Animals 2015, 5, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powdrill-Wells, N.; Taylor, S.; Melfi, V. Reducing dog relinquishment to rescue centres due to behaviour problems: Identifying cases to target with an advice intervention at the point of relinquishment request. Animals 2021, 11, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, E.; Gramann, S.; Victor Spain, C.; Slater, M. Goodbye to a Good Friend: An Exploration of the Re-Homing of Cats and Dogs in the U.S. Open J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 05, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, M.M.; Jackson, J.A.; Line, S.W.; Anderson, R.K. Evaluation of association between retention in the home and attendance at puppy socialization classes. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 223, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzano, A.; Bianchi, L.; Campa, S.; Mariti, C. The prevention of undesirable behaviors in cats: Effectiveness of veterinary behaviorists’ advice given to kitten owners. J. Vet. Behav. 2015, 10, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Di Clemente, C.C. Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy 1982, 19, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, S.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Tucker, P.; Di Sebastiano, K.M.; Faulkner, G. The use of the behaviour change wheel in the development of ParticipACTION’s physical activity app. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 20, 101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coupe, N.; Cotterill, S.; Peters, S. Enhancing community weight loss groups in a low socioeconomic status area: Application of the COM-B model and Behaviour Change Wheel. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 2043–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.C.; McLeod, L.J. Understanding the Factors Influencing Cat Containment: Identifying Opportunities for Behaviour Change. Animals 2023, 13, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiClemente, C.C.; Prochaska, J.O.; Fairhurst, S.K.; Velicer, W.F.; Velasquez, M.M.; Rossi, J.S. The Process of Smoking Cessation: An Analysis of Precontemplation, Contemplation, and Preparation Stages of Change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni Mhurchu, C.; Margetts, B.M.; Speller, V.M. Applying the stages-of-change model to dietary change. Nutr. Rev. 1997, 55, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchill, J.; Ward, E. Communicating with Pet Owners About Obesity: Roles of the Veterinary Health Care Team. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2016, 46, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckman, H.; Hiby, E. The role of human behaviour change in companion animal management: A case study of Praia de Faro, Portugal. Hum. Anim. Interact. 2024, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, M.; Phillips, C.J.C. Key tenets of operational success in international animal welfare initiatives. Animals 2018, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.; Lee, N.Y.P.; White, J.; Bell, C. Perceptions of Cross-Cultural Challenges and Successful Approaches in Facilitating the Improvement of Equine Welfare. Animals 2023, 13, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddy, E.; Brown, J.; Burden, F.; Raw, Z.; Kaminski, J.; Proops, L. “What can we do to actually reach all these animals?” Evaluating approaches to improving working equid welfare. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanville, C.; Ford, J.; Cook, R.; Coleman, G.J. Community Attitudes Reflect Reporting Rates and Prevalence of Animal Mistreatment. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 666727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, B.; Fjæran, E.H. From Stakeholder Education to Engagement, Using Strategies from Social Science. In Changing Human Behaviour to Enhance Animal Welfare; Sommerville, R., Ed.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, S.; Lips, D. Stakeholder’s attitudes to and engagement for animal welfare: To participation and cocreation. In Ethics and the Politics of Food; Kaiser, M., Lien, M.E., Eds.; Brill—Wageningen Academic: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, J.M.; Salman, M.D.; New, J.G.; Kass, P.H. Reasons for Relinquishment of Companion Animals in U.S. Animal Shelters: Selected Health and Personal Issues. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 1999, 2, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.Y.; Paterson, M.B.A.; Phillips, C.J.C. Socioeconomic influences on reports of canine welfare concerns to the royal society for the prevention of cruelty to animals (RSPCA) in Queensland, Australia. Animals 2019, 9, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leask, C.F.; Sandlund, M.; Skelton, D.A.; Altenburg, T.M.; Cardon, G.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Verloigne, M.; Chastin, S.F.M. Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co-creation and evaluation of public health interventions. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2019, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allender, S.; Owen, B.; Kuhlberg, J.; Lowe, J.; Nagorcka-Smith, P.; Whelan, J.; Bell, C. A community based systems diagram of obesity causes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A.; Wu, H.; Morales, C. Barriers to Care in Veterinary Services: Lessons Learned From Low-Income Pet Guardians’ Experiences at Private Clinics and Hospitals During COVID-19. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 20, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, L.R.; Accornero, V.H.; Gelb, E.; Slater, M.R. Community Veterinary Medicine Programs: Pet Owners’ Perceptions and Experiences. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 678595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopopova, A.; Gunter, L.M. Adoption and relinquishment interventions at the animal shelter: A review. Anim. Welf. 2017, 26, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, L.; Protopopova, A.; Hooker, S.P.; Der Ananian, C.; Wynne, C.D.L. Impacts of Encouraging Dog Walking on Returns of Newly Adopted Dogs to a Shelter. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2017, 20, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Dowling-Guyer, S.; McCobb, E. Community Programming for Companion Dog Retention: A Survey of Animal Welfare Organizations. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2023, 26, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, L.A. Pets along a continuum: Response to “What is a pet?”. Anthrozoos 2003, 16, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MapHub Homepage. Available online: https://maphub.net/ (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Franco-Trigo, L.; Hossain, L.N.; Durks, D.; Fam, D.; Inglis, S.C.; Benrimoj, S.I.; Sabater-Hernández, D. Stakeholder analysis for the development of a community pharmacy service aimed at preventing cardiovascular disease. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2017, 13, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Trigo, L.; Marqués-Sánchez, P.; Tudball, J.; Benrimoj, S.I.; Martínez-Martínez, F.; Sabater-Hernández, D. Collaborative health service planning: A stakeholder analysis with social network analysis to develop a community pharmacy service. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, C.R.; Bevelander, K.E.; de Leeuw, R.N.H.; Buijzen, M. Motivating Social Influencers to Engage in Health Behavior Interventions. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 885688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumba, J. The Use and Value of Mixed Methods Research in Social Work. Adv. Soc. Work. 2013, 14, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKim, C.A. The Value of Mixed Methods Research: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Mix Methods Res. 2017, 11, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SurveyMonkey Inc. SurveyMonkey. Available online: https://www.surveymonkey.com (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Rohlf, V.I.; Bennett, P.C.; Toukhsati, S.; Coleman, G. Why do even committed dog owners fail to comply with some responsible ownership practices? Anthrozoos 2010, 23, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savard, I.; Kilpatrick, K. Tailoring research recruitment strategies to survey harder-to-reach populations: A discussion paper. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Video Conferencing, Meetings, Calls—Microsoft Teams. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-gb/microsoft-teams/group-chat-software (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Holland, K.E.; Mead, R.; Casey, R.A.; Upjohn, M.M.; Christley, R.M. “Don’t Bring Me a Dog…I’ll Just Keep It”: Understanding Unplanned Dog Acquisitions Amongst a Sample of Dog Owners Attending Canine Health and Welfare Community Events in the United Kingdom. Animals 2021, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions, 1st ed.; Silverback Publishing: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-912141-00-5. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, L.K.; Saunders, J.M.; Cassell, J.; Curtis, T.; Bastaki, H.; Hartney, T.; Rait, G. Application of the COM-B model to barriers and facilitators to chlamydia testing in general practice for young people and primary care practitioners: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.E.B.; Richardson, K.; Halil-Pizzirani, B.; Atkins, L.; Yücel, M.; Segrave, R.A. Key influences on university students’ physical activity: A systematic review using the Theoretical Domains Framework and the COM-B model of human behaviour. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Jover, M.; Randle, H.; Manyweathers, J.; Furtado, T. Exploring human behavior change in equine welfare: Insights from a COM-B analysis of the UK’s equine obesity epidemic. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 961537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Hockenhull, J.; Jobling, R.; Rono, D.; Kavata, L.; Rogers, S. Using Human Behaviour Change Science to Investigate Use of Whips on Working Donkeys. Available online: https://www.thebrooke.org/sites/default/files/Downloads/using-human-behaviour-change-science-to-investigate-use-of-whips-on-working-donkeys.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Hockenhull, J.; Rogers, S.; Eckman, H.; Payne, M. Using the COM-B Model to Explore the Reasons People Attended Seaworld San Diego Between 2015 and 2019. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2022, 17, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Arden, M.A. How Useful Are the Stages of Change for Targeting Interventions? Randomized Test of a Brief Intervention to Reduce Smoking. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaVallee, E.; Mueller, M.K.; McCobb, E. A Systematic Review of the Literature Addressing Veterinary Care for Underserved Communities. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2017, 20, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollwitzer, P.M. Goal Achievement: The Role of Intentions. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 4, 141–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Luszczynska, A. Implementation intention and action planning interventions in health contexts: State of the research and proposals for the way forward. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2014, 6, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutter, E.R.; Oettingen, G.; Gollwitzer, P.M. An online randomised controlled trial of mental contrasting with implementation intentions as a smoking behaviour change intervention. Psychol. Health 2020, 35, 318–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Godin, G.; Amireault, S. A meta-analytic review of the effect of implementation intentions on physical activity. Health Psychol. Rev. 2013, 7, 23–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaanse, M.A.; Vinkers, C.D.W.; De Ridder, D.T.D.; Hox, J.J.; De Wit, J.B.F. Do implementation intentions help to eat a healthy diet? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Appetite 2011, 56, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Sims, R. Improving equine welfare through human habit formation. Animals 2021, 11, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, G.; Magee, P. Co-creation solutions and the three Co’s framework for applying Co-creation. Health Educ. 2024, 124, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, E.J.; Casey, R.A.; Bradshaw, J.W.S. Efficacy of written behavioral advice for separation-related behavior problems in dogs newly adopted from a rehoming center. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 12, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.G.; Kim, K.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Church, D.B.; Pegram, C.; Baldrey, V. Demography, disorders and mortality of pet hamsters under primary veterinary care in the United Kingdom in 2016. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2022, 63, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, L.R.; Hawes, S.M.; Connolly, K.; Bergstrom, M.; O’Reilly, K.; Morris, K.N. Animal Control and Field Services Officers’ Perspectives on Community Engagement: A Qualitative Phenomenology Study. Animals 2023, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.L.; Clements, J. Engaging with socio-economically disadvantaged communities and their cats: Human behaviour change for animal and human benefit. Animals 2019, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Rock, M.; Bondo, K.; van der Meer, F.; Kutz, S. 11 years of regular access to subsidized veterinary services is associated with improved dog health and welfare in remote northern communities. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 196, 105471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, J.; Johnston, N. Impact of a Subsidized Spay Neuter Clinic on Impoundments and Euthanasia in a Community Shelter and on Service and Complaint Calls to Animal Control. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2012, 15, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Bains, R.S.; Morris, A.; Morales, C. Affordability, feasibility, and accessibility: Companion animal guardians with (dis)abilities’ access to veterinary medical and behavioral services during COVID-19. Animals 2021, 11, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, E.R.; Petersen, C.L.; Douglas, D.K. Moving as a Reason for Pet Relinquishment: A Closer Look. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2003, 6, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.M.; Carlisle-Frank, P.L. Analysis of programs to reduce overpopulation of companion animals: Do adoption and low-cost spay/neuter programs merely cause substitution of sources? Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterell, J.L.; Rand, J.; Barnes, T.S.; Scotney, R. Impact of a Local Government Funded Free Cat Sterilization Program for Owned and Semi-Owned Cats. Animals 2024, 14, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, R.; Morales, C. Trauma in Animal Protection and Welfare Work: The Potential of Trauma-Informed Practice. Animals 2022, 12, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J.; Reese, L.A. Compassion Fatigue Among Animal Shelter Volunteers: Examining Personal and Organizational Risk Factors. Anthrozoos 2021, 34, 803–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurer, J.M.; Phipps, K.; Okemow, C.; Beatch, H.; Jenkins, E. Stabilizing Dog Populations and Improving Animal and Public Health Through a Participatory Approach in Indigenous Communities. Zoonoses Public Health 2015, 62, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodyear, M.D.; Krleza-Jeric, K. The Declaration of Helsinki. BMJ 2007, 335, 624–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Participants | Survey Themes | Responses Received |

|---|---|---|

| Community team members |

| 13 |

| Wider Woodgreen team |

| 17 |

| Target Participants | Survey Themes | Responses Received |

|---|---|---|

| Pet owners with the Littleport community |

| 69 |

| Littleport community members (including those who own pets) |

| 56 |

| Professionals working with pet owners in the Littleport community |

| 11 |

| What behaviour? | Pet owners within the target community need to take their pets for timely veterinary treatment. |

| Where does the behaviour occur? | Veterinary clinic |

| Who is involved in performing the behaviour? | Pet owners within the target community |

| 1 | Who needs to perform the behaviour? | Pet owners in the target community |

| 2 | What do they need to do differently to achieve the desired change? | Get a health check for their pet. |

| 3 | When do they need to do it? | Once a year |

| 4 | Where do they need to do it? | Veterinary clinic, Woodgreen clinic, home visits |

| 5 | How often do they need to do it? | Annually |

| 6 | With whom do they need to do it | Woodgreen or a vet |

| COM-B Components | What Needs to Happen for the Target Behaviour to Occur? | Is There a Need to Change? |

|---|---|---|

| Physical capability | Owners need to be able to book and attend a health check Owner needs to be able to transport and handle animals for appointment | Maybe, for some health checks need to be more accessible |

| Psychological capability | Owner is aware of the health check provision and how to book Owner can remember to book and go to an appointment | Maybe, for some communication needs to be provided on multiple channels and different booking methods available |

| Physical opportunity | Owner has money to pay for a check Owner has time to attend an appointment Owner has access to transport to travel to an appointment with a pet | Yes, important to consider accessibility for all in the design of health check |

| Social opportunity | Other pet owners in the community can also be seen to be accessing health check Support from family and friends to attend the health check | Yes, we know that not all pet owners are performing this as a norm. There is a need to make the decision to attend an annual health check socially desirable. |

| Reflective motivation | Pet owners need to understand the benefits of preventative health Owners need to feel confident they can access the health check Owners feel health checks are an important part of being a responsible owner | Yes, there is a need for clearer communication of the welfare benefits and cost savings of preventative care |

| Automatic motivation | Pet owners feel positive emotional feedback and reinforcement in seeing their pet being cared for in a positive way | Maybe, some pet owners are taking on preventative health checks but not all |

| Behavioural diagnosis of the relevant COM-B components | The focus should be on making health checks accessible to all owners; they should be seen as normal behaviour in the community for pet owners to do and the benefits of preventative health care should be widely known and understood. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Powdrill-Wells, N.; Bennett, C.; Cooke, F.; Rogers, S.; White, J. A Novel Approach to Engaging Communities Through the Use of Human Behaviour Change Models to Improve Companion Animal Welfare and Reduce Relinquishment. Animals 2025, 15, 1036. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15071036

Powdrill-Wells N, Bennett C, Cooke F, Rogers S, White J. A Novel Approach to Engaging Communities Through the Use of Human Behaviour Change Models to Improve Companion Animal Welfare and Reduce Relinquishment. Animals. 2025; 15(7):1036. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15071036

Chicago/Turabian StylePowdrill-Wells, Natalie, Chris Bennett, Fiona Cooke, Suzanne Rogers, and Jo White. 2025. "A Novel Approach to Engaging Communities Through the Use of Human Behaviour Change Models to Improve Companion Animal Welfare and Reduce Relinquishment" Animals 15, no. 7: 1036. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15071036

APA StylePowdrill-Wells, N., Bennett, C., Cooke, F., Rogers, S., & White, J. (2025). A Novel Approach to Engaging Communities Through the Use of Human Behaviour Change Models to Improve Companion Animal Welfare and Reduce Relinquishment. Animals, 15(7), 1036. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15071036