Specific Neural Mechanisms Underlying Humans’ Processing of Information Related to Companion Animals: A Comparison with Domestic Animals and Objects

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Materials, Scales and Procedure

2.2.1. Preparation and Evaluation of Experimental Materials

2.2.2. Questionnaire Survey

2.2.3. Experimental Procedure

2.3. Functional MRI Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Specific Activation Analysis for Processing Companion Animal Information

2.4.2. Correlation Analysis Between Brain Activation and Questionnaire Data

2.4.3. Exploratory Generalized PsychoPhysiological Interaction Analysis

2.4.4. Exploratory Dynamic Causal Modeling Analysis

2.5. Auxiliary Tool—Usage of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI)

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Variable Statistics

3.2. Specificity of Neural Mechanisms in Processing Companion Animal Information

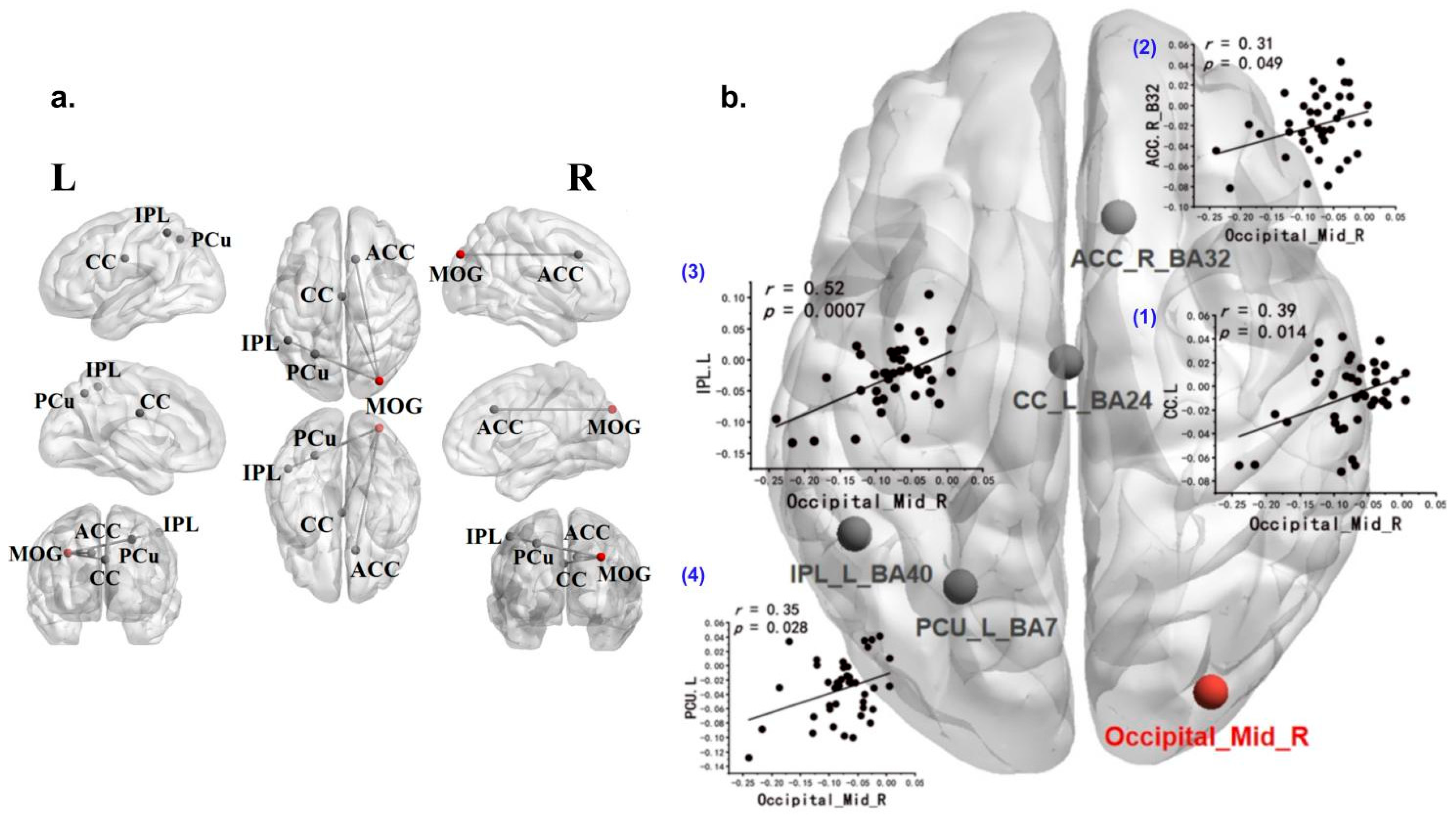

3.3. Correlation Between Brain Activation and Behavioral Data

3.4. Exploratory Generalized Psychophysiological Interaction Analysis

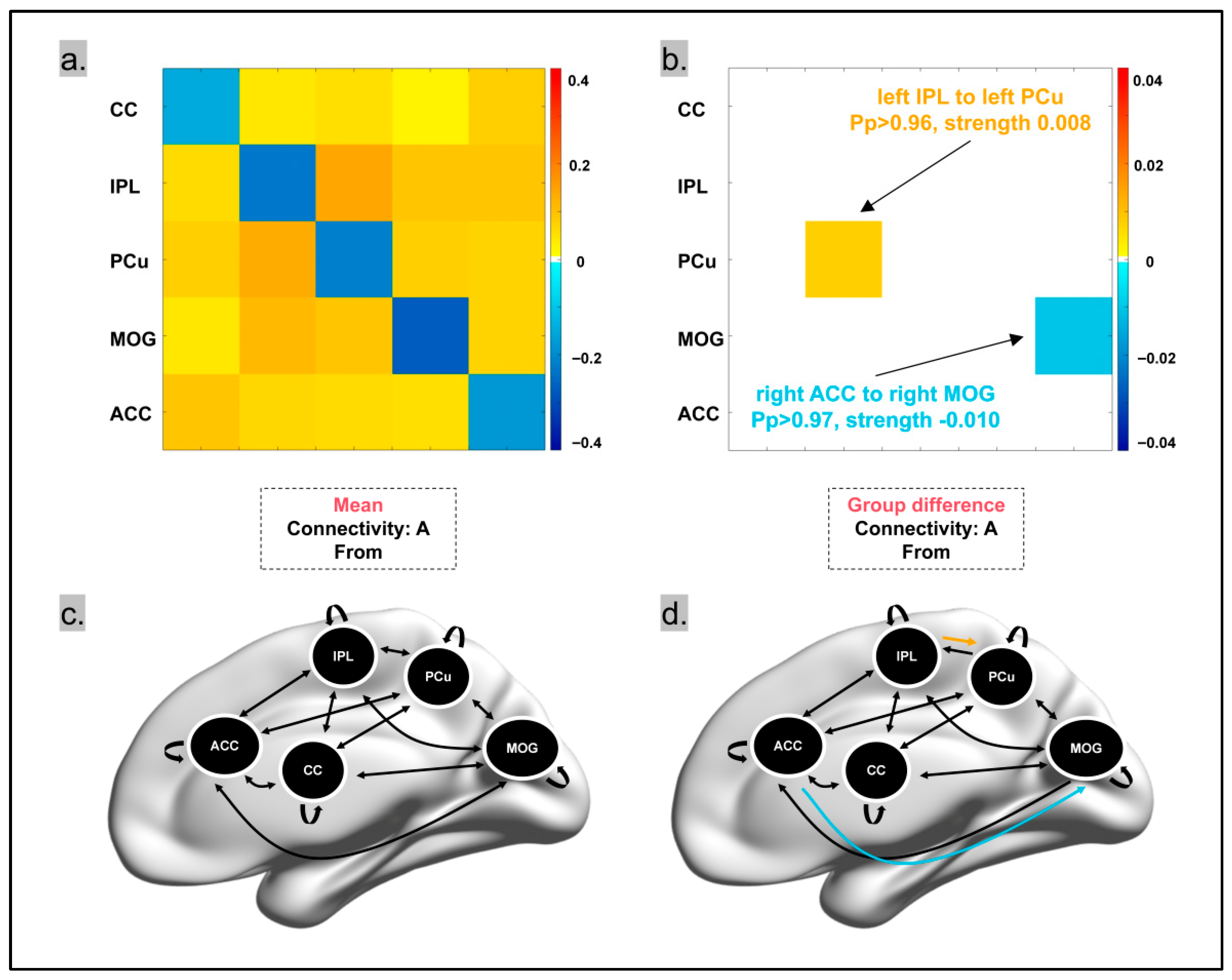

3.5. Exploratory Dynamic Causal Modeling Analysis

- (1)

- The connectivity from the left IPL to the left PCu was significantly stronger in pet owners, with a difference of 0.008 compared to non-pet owners (Pp > 0.96) (Figure 5);

- (2)

- The connectivity from the right ACC to the right MOG was significantly weaker in pet owners, with a difference of −0.01 compared to non-pet owners (Pp > 0.97).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanders, S. 125 Questions: Exploration and Discovery; Science/AAAS Custom Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, D.L. The state of research on human–animal relations: Implications for human health. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma-Brymer, V.; Dashper, K.; Brymer, E.; IsHak, W.W. Nature and pets. In Handbook of Wellness Medicine; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Souter, M.A.; Miller, M.D. Do animal-assisted activities effectively treat depression? A meta-analysis. Anthrozoös 2007, 20, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, P.P. The ecological cost of pets. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R955–R956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, C.; Ruple, A. Canine sentinels and our shared exposome. Science 2024, 384, 1170–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.D.; Hawkins, E.L.; Tip, L. “I can’t give up when I have them to care for”: People’s experiences of pets and their mental health. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollami, A.; Gianferrari, E.; Alfieri, E.; Artioli, G.; Taffurelli, C. Pet therapy: An effective strategy to care for the elderly? An experimental study in a nursing home. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2017, 88 (Suppl. S1), 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, C.F.; Soares, J.P.; Cortinhas, A.; Silva, L.; Cardoso, L.; Pires, M.A.; Mota, M.P. Pet’s influence on humans’ daily physical activity and mental health: A meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1196199. [Google Scholar]

- Curl, A.L.; Bibbo, J.; Johnson, R.A. Dog walking, the human–animal bond and older adults’ physical health. Gerontologist 2017, 57, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, N.; Zilcha-Mano, S.; Zukerman, S.; Josman, N. Cognitive Function and Participation of Stroke Survivors Living with Companion Animals: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2024, 15, 21501319241240356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applebaum, J.W.; Shieu, M.M.; McDonald, S.E.; Dunietz, G.L.; Braley, T.J. The impact of sustained ownership of a pet on cognitive health: A population-based study. J. Aging Health 2023, 35, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, M.; Eshuis, J.; Peeters, S.; Lataster, J.; Reijnders, J.; Enders-Slegers, M.-J.; Jacobs, N. The pet-effect in daily life: An experience sampling study on emotional wellbeing in pet owners. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junça-Silva, A.; Almeida, M.; Gomes, C. The role of dogs in the relationship between telework and performance via affect: A moderated moderated mediation analysis. Animals 2022, 12, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, M.; Janssens, E.; Eshuis, J.; Lataster, J.; Simons, M.; Reijnders, J.; Jacobs, N. Companion animals as buffer against the impact of stress on affect: An experience sampling study. Animals 2021, 11, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathish, D.; Rajapakse, J.; Weerakoon, K. In times of stress, it is good to be with them”: Experience of dog owners from a rural district of Sri Lanka. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, L.R.; Currin-McCulloch, J.; Bussolari, C.; Packman, W.; Erdman, P. The psychosocial influence of companion animals on positive and negative affect during the COVID-19 pandemic. Animals 2021, 11, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer, A.; Hunt, M.; Chowdhury, M.; Nicol, L. Effects of a brief mindfulness meditation intervention on student stress and heart rate variability. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2016, 23, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagwood, K.; Vincent, A.; Acri, M.; Morrissey, M.; Seibel, L.; Guo, F.; Flores, C.; Seag, D.; Pierce, R.P.; Horwitz, S. Reducing anxiety and stress among youth in a CBT-based equine-assisted adaptive riding program. Animals 2022, 12, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H.L.; Rushton, K.; Lovell, K.; Bee, P.; Walker, L.; Grant, L.; Rogers, A. The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.-K.; Kam, P.K. Conditions for pets to prevent depression in older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1627–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junça-Silva, A. Friends with benefits: The positive consequences of pet-friendly practices for workers’ well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Ohtani, N.; Ohta, M. The effects of touching and stroking a cat on the inferior frontal gyrus in people. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, A.; Aiba, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Takahashi, M.; Kido, H.; Suzuki, T.; Bando, Y. Stroking a real horse versus stroking a toy horse: Effects on the frontopolar area of the human brain. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, A.; Masud, M.M.; Yokoyama, A.; Mizutani, W.; Watanuki, S.; Yanai, K.; Itoh, M.; Tashiro, M. Effects of presence of a familiar pet dog on regional cerebral activity in healthy volunteers: A positron emission tomography study. Anthrozoös 2012, 25, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Stoeckel, L.; Palley, L.S.; Gollub, R.L.; Niemi, S.M.; Evins, A.E. Patterns of brain activation when mothers view their own child and dog: An fMRI study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.J.; Verreynne, M.-L.; Harpur, P.; Pachana, N.A. Companion animals and health in older populations: A systematic review. Clin. Gerontol. 2020, 43, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Qushayri, A.E.; Kamel, A.M.A.; Faraj, H.A.; Vuong, N.L.; Diab, O.M.; Istanbuly, S.; Elshafei, T.A.; Makram, O.M.; Sattar, Z.; Istanbuly, O.; et al. Association between pet ownership and cardiovascular risks and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 21, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polheber, J.P.; Matchock, R.L. The presence of a dog attenuates cortisol and heart rate in the Trier Social Stress Test compared to human friends. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 37, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.; Edwards, K.M.; Michael, S.; McGreevy, P.; Bauman, A.; Guastella, A.J.; Drayton, B.; Stamatakis, E. Effects of human–dog interactions on salivary oxytocin concentrations and heart rate variability: A four-condition cross-over trial. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, T.; Kimura, Y.; Masuda, K.; Uchiyama, H. Effects of interactions with cats in domestic environment on the psychological and physiological state of their owners: Associations among cortisol, oxytocin, heart rate variability, and emotions. Animals 2023, 13, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendry, P.; Vandagriff, J.L. Animal visitation program (AVP) reduces cortisol levels of university students: A randomized controlled trial. AERA Open 2019, 5, 2332858419852592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Jinez, A.; López-Rincón, F.J.; Ugarte-Esquivel, A.; Andrade-Valles, I.; Rodríguez-Mejía, L.E.; Hernández-Torres, J.L. Carga alostática y compañía canina: Un estudio comparativo mediante biomarcadores en adultos mayores. Rev. Lat.-Am. De Enferm. 2018, 26, e3071. [Google Scholar]

- Odendaal, J.S.J.; Lehmann, S.M.C. The role of phenylethylamine during positive human-dog interaction. Acta Veter. Brno 2000, 69, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendaal, J.; Meintjes, R. Neurophysiological correlates of affiliative behaviour between humans and dogs. Veter. J. 2003, 165, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creagan, E.T.; Bauer, B.A.; Thomley, B.S.; Borg, J.M. Animal-assisted therapy at Mayo Clinic: The time is now. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pr. 2015, 21, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, L.F.; Santaniello, A.; Amato, A.; Ceparano, G.; Di Maggio, A.; Sansone, M.; Formisano, P.; Cimmino, I.; Perruolo, G.; Fioretti, A. Changes of oxytocin and serotonin values in dialysis patients after animal assisted activities (AAAs) with a dog—A preliminary study. Animals 2019, 9, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, J. The neurobiology of attachment: From infancy to clinical outcomes. Psychodyn. Psychiatry 2017, 45, 542–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, P.; Duschinsky, R. Attachment Theory and Research. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, M.; Massavelli, B.; Pachana, N. Using attachment theory and social support theory to examine and measure pets as sources of social support and attachment figures. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia, the Human Bond with Other Species; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia and the Conservation Ethic. In The Biophilia Hypothesis; Kellert, S.A., Wilson, E.O., Eds.; Shearwater Books: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marti, R.; Petignat, M.; Marcar, V.L.; Hattendorf, J.; Wolf, M.; Hund-Georgiadis, M.; Hediger, K. Effects of contact with a dog on prefrontal brain activity: A controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayama, S.; Chang, L.; Gumus, K.; King, G.R.; Ernst, T. Neural correlates for perception of companion animal photographs. Neuropsychologia 2016, 85, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormann, F.; Dubois, J.; Kornblith, S.; Milosavljevic, M.; Cerf, M.; Ison, M.; Tsuchiya, N.; Kraskov, A.; Quiroga, R.Q.; Adolphs, R.; et al. A category-specific response to animals in the right human amygdala. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 1247–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sable, P. The pet connection: An attachment perspective. Clin. Soc. Work. J. 2013, 41, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, K.R.; Behnke, A.C.; Udell, M.A. Attachment bonds between domestic cats and humans. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R864–R865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds, A.M. Foundations of the Positive Affect Tolerance Protocol: The Central Role of Interpersonal Positive Affect in Attachment and Self-Regulation. J. EMDR Pr. Res. 2023, 17, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handlin, L.; Hydbring-Sandberg, E.; Nilsson, A.; Ejdebäck, M.; Jansson, A.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K. Short-term interaction between dogs and their owners: Effects on oxytocin, cortisol, insulin and heart rate—An exploratory study. Anthrozoös 2011, 24, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, K.; Nagasawa, M.; Onaka, T.; Kanemaki, N.; Nakamura, S.; Tsubota, K.; Mogi, K.; Kikusui, T. Increase of tear volume in dogs after reunion with owners is mediated by oxytocin. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R869–R870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.W.; Wong, D.F.K. Effects of Companion Dogs on Adult Attachment, Emotion Regulation, and Mental Wellbeing in Hong Kong. Soc. Anim. 2022, 30, 668–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, G.; Yang, J. Unconscious processing of negative animals and objects: Role of the amygdala revealed by fMRI. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y.; Ebara, F.; Morita, Y.; Horikawa, E. Near-infrared spectroscopy can reveal increases in brain activity related to animal-assisted therapy. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 1429–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, V.A.; Cheon, B.K.; Harada, T.; Scimeca, J.M.; Chiao, J.Y. Overlapping neural response to the pain or harm of people, animals, and nature. Neuropsychologia 2016, 81, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yoo, O.; Wu, Y.; Han, J.S.; Park, S.-A. Psychophysiological and emotional effects of human–Dog interactions by activity type: An electroencephalogram study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulick, E.E.; Krause-Parello, C.A. Factors related to type of companion pet owned by older women. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2012, 50, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodburn, M.; Bricken, C.L.; Wu, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, L.; Lin, W.; Sheridan, M.A.; Cohen, J.R. The maturation and cognitive relevance of structural brain network organization from early infancy to childhood. NeuroImage 2021, 238, 118232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, D.N.; Maguire, E.A. Remote memory and the hippocampus: A constructive critique. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axer, M.; Amunts, K. Scale matters: The nested human connectome. Science 2022, 378, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Liu, Q.; Dadgar-Kiani, E. Solving brain circuit function and dysfunction with computational modeling and optogenetic fMRI. Science 2022, 378, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Schotten, M.T.; Forkel, S.J. The emergent properties of the connected brain. Science 2022, 378, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Mu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Feng, J. Identifying individual brain development using multimodality brain network. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, J.E.; Glover, G.H. Estimating sample size in functional MRI (fMRI) neuroimaging studies: Statistical power analyses. J. Neurosci. Methods 2002, 118, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, J.; Chin, V. Trust and reciprocity: Foundational principles for human subjects imaging research. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007, 34, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, D.G.; Ries, M.L.; Xu, G.; Johnson, S.C. A generalized form of context-dependent psychophysiological interactions (gPPI): A comparison to standard approaches. NeuroImage 2012, 61, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J.; Harrison, L.; Penny, W. Dynamic causal modelling. NeuroImage 2003, 19, 1273–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Basic books: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Keefer, L.A.; Landau, M.J.; Sullivan, D. Non-human support: Broadening the scope of attachment theory. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2014, 8, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J. The Importance of Attachment for Human Beings and Dogs-Implications for Dog-Assisted Psychotherapy. Prax. Der. Kinderpsychol. Und Kinderpsychiatr. 2023, 72, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, R. The neurobiology of human attachments. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yankouskaya, A.; Denholm-Smith, T.; Yi, D.; Greenshaw, A.J.; Cao, B.; Sui, J. Neural connectivity underlying reward and emotion-related processing: Evidence from a large-scale network analysis. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 833625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesage, E.; Stein, E.A. Networks associated with reward. In Neuroscience in the 21st Century: From Basic to Clinical; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1991–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Verharen, J.P.H.; Adan, R.A.H.; Vanderschuren, L.J.M.J. How reward and aversion shape motivation and decision making: A computational account. Neuroscientist 2020, 26, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyten, P.; Fonagy, P. The neurobiology of mentalizing. Personal. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 2015, 6, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliemann, D.; Adolphs, R. The social neuroscience of mentalizing: Challenges and recommendations. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellal, F. Anatomical and neurophysiological basis of face recognition. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 178, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuniecki, M.; Wołoszyn, K.; Domagalik, A.; Pilarczyk, J. Disentangling brain activity related to the processing of emotional visual information and emotional arousal. Anat. Embryol. 2018, 223, 1589–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.W.; Sabatinelli, D. Hemodynamic and electrocortical reactivity to specific scene contents in emotional perception. Psychophysiology 2019, 56, e13340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapelli, I.; Özkurt, T.E. Brain oscillatory correlates of visual short-term memory errors. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Q.; Johnson, E.L.; Tang, L.; Auguste, K.I.; Knight, R.T.; Asano, E.; Ofen, N. Direct brain recordings reveal occipital cortex involvement in memory development. Neuropsychologia 2020, 148, 107625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Luo, G.; Li, T.; Chatterjee, A.; Zhang, W.; He, X. The neural mechanism of aesthetic judgments of dynamic landscapes: An fMRI study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K.; Brown, E.C.; Matsuzaki, N.; Asano, E. Animal category-preferential gamma-band responses in the lower-and higher-order visual areas: Intracranial recording in children. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 2368–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Borgi, M.; Cirulli, F. Pet face: Mechanisms underlying human-animal relationships. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.W.; Downey, D.; Strachan, H.; Elliott, R.; Williams, S.R.; Abel, K.M. The neural basis of maternal bonding. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibenluft, E.; Gobbini, M.; Harrison, T.; Haxby, J.V. Mothers’ neural activation in response to pictures of their children and other children. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 56, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, J.B.; Nelson, E.E.; Rusch, B.D.; Fox, A.S.; Oakes, T.R.; Davidson, R.J. Orbitofrontal cortex tracks positive mood in mothers viewing pictures of their newborn infants. NeuroImage 2004, 21, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Takiguchi, S.; Mizushima, S.; Fujisawa, T.X.; Saito, D.N.; Kosaka, H.; Okazawa, H.; Tomoda, A. Reduced visual cortex grey matter volume in children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder. NeuroImage Clin. 2015, 9, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Putnick, D.L.; Rigo, P.; Esposito, G.; Swain, J.E.; Suwalsky, J.T.D.; Su, X.; Du, X.; Zhang, K.; Cote, L.R.; et al. Neurobiology of culturally common maternal responses to infant cry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E9465–E9473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, S.I.; Stoycos, S.A.; Sellery, P.; Marshall, N.; Khoddam, H.; Kaplan, J.; Goldenberg, D.; Saxbe, D.E. Theory of mind processing in expectant fathers: Associations with prenatal oxytocin and parental attunement. Dev. Psychobiol. 2021, 63, 1549–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, E.M.; Bezek, J.; Siegal, O.; Freitag, G.F.; Subar, A.; Khosravi, P.; Mallidi, A.; Peterson, O.; Morales, I.; Haller, S.P.; et al. Multivariate Assessment of Inhibitory Control in Youth: Links with Psychopathology and Brain Function. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 35, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Applications of attachment theory and research: The blossoming of relationship science. In Applications of Social Psychology; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Palomero-Gallagher, N.; Amunts, K. A short review on emotion processing: A lateralized network of neuronal networks. Brain Struct. Funct. 2022, 227, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roesmann, K.; Dellert, T.; Junghoefer, M.; Kissler, J.; Zwitserlood, P.; Zwanzger, P.; Dobel, C. The causal role of prefrontal hemispheric asymmetry in valence processing of words–Insights from a combined cTBS-MEG study. NeuroImage 2019, 191, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.J.; Taylor, M.J.; Hong, S.-B.; Kim, C.; Yi, S.-H. The neural correlates of attachment security in typically developing children. Brain Cogn. 2018, 124, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, D.J.; Harmon-Jones, E. On the neuroscience of approach and withdrawal motivation, with a focus on the role of asymmetrical frontal cortical activity. In Recent Developments in Neuroscience Research on Human Motivation; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2016; pp. 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Moutsiana, C.; Charpentier, C.J.; Garrett, N.; Cohen, M.X.; Sharot, T. Human frontal–subcortical circuit and asymmetric belief updating. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 14077–14085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Walker, Z.M.; Hale, J.B.; Chen, S.A. Frontal-subcortical circuitry in social attachment and relationships: A cross-sectional fMRI ALE meta-analysis. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 325, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Mariti, C.; Zdeinert, A.; Riggio, G.; Mora-Medina, P.; Reyes, A.d.M.; Gazzano, A.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Lezama-García, K.; José-Pérez, N.; et al. Anthropomorphism and its adverse effects on the distress and welfare of companion animals. Animals 2021, 11, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, B.M.; Peirce, K.; Caeiro, C.C.; Scheider, L.; Burrows, A.M.; McCune, S.; Kaminski, J. Paedomorphic facial expressions give dogs a selective advantage. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, A.M.; Kaminski, J.; Waller, B.M.; Omstead, K.M.; Rogers-Vizena, C.; Mendelson, B. Dog faces exhibit anatomical differences in comparison to other domestic animals. Anat. Rec. Adv. Integr. Anat. Evol. Biol. 2020, 304, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, C.L.; Diogo, R.; Subiaul, F.; Bradley, B.J. Raising an Eye at Facial Muscle Morphology in Canids. Biology 2024, 13, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, J.; Waller, B.M.; Diogo, R.; Hartstone-Rose, A.; Burrows, A.M. Evolution of facial muscle anatomy in dogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 14677–14681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, I.M.; Erwin, H.B.; Sin, N.L.; Allen, R.S. Pet ownership is associated with greater cognitive and brain health in a cross-sectional sample across the adult lifespan. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 953889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dipnall, L.M.; Hourani, D.; Darling, S.; Anderson, V.; Sciberras, E.; Silk, T.J. Fronto-parietal white matter microstructure associated with working memory performance in children with ADHD. Cortex 2023, 166, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, Y.; Song, R.W.; Springer, S.D.; John, J.A.; Embury, C.M.; Killanin, A.D.; Son, J.J.; Okelberry, H.J.; McDonald, K.M.; Picci, G.; et al. High-definition transcranial direct current stimulation of the parietal cortices modulates the neural dynamics underlying verbal working memory. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2024, 45, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogler, C.; Zangrossi, A.; Miller, C.; Sartori, G.; Haynes, J. Have you been there before? Decoding recognition of spatial scenes from fMRI signals in precuneus. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2024, 45, e26690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numssen, O.; Bzdok, D.; Hartwigsen, G. Functional specialization within the inferior parietal lobes across cognitive domains. eLife 2021, 10, e63591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, S.; Peverelli, M.; Bertoni, S.; Ruffino, M.; Ronconi, L.; Molteni, F.; Priftis, K.; Facoetti, A. The engagement of temporal attention in left spatial neglect. Cortex 2024, 178, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porada, D.K.; Regenbogen, C.; Freiherr, J.; Seubert, J.; Lundström, J.N. Trimodal processing of complex stimuli in inferior parietal cortex is modality-independent. Cortex 2021, 139, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santacroce, F.; Cachia, A.; Fragueiro, A.; Grande, E.; Roell, M.; Baldassarre, A.; Sestieri, C.; Committeri, G. Human intraparietal sulcal morphology relates to individual differences in language and memory performance. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVarco, A.; Ahmad, N.; Archer, Q.; Pardillo, M.; Nunez Castaneda, R.; Minervini, A.; Keenan, J.P. Self-conscious emotions and the right fronto-temporal and right temporal parietal junction. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zheng, X.; Yao, S.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Li, K.; Zhao, W.; Li, H.; Becker, B.; Kendrick, K.M. The mirror neuron system compensates for amygdala dysfunction-associated social deficits in individuals with higher autistic traits. NeuroImage 2022, 251, 119010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, T.; Filmer, H.L.; Dux, P.E. On the role of prefrontal and parietal cortices in mind wandering and dynamic thought. Cortex 2024, 178, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman-Shalem, M.; Dunbar, R.I.M.; Arzy, S. Processing of social closeness in the human brain. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, T.-H.H.; Lee, B.; Hsu, L.-M.; Cerri, D.H.; Zhang, W.-T.; Wang, T.-W.W.; Ryali, S.; Menon, V.; Shih, Y.-Y.I. Neuronal dynamics of the default mode network and anterior insular cortex: Intrinsic properties and modulation by salient stimuli. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Cai, H.; Chen, L.; Gu, M.; Tchieu, J.; Guo, F. Functional Neural Networks in Human Brain Organoids. BME Front. 2024, 5, 0065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymbs, N.F.; Nebel, M.B.; Ewen, J.B.; Mostofsky, S.H. Altered inferior parietal functional connectivity is correlated with praxis and social skill performance in children with autism spectrum disorder. Cereb. Cortex 2021, 31, 2639–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Tian, J.; Yuan, P.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Y. Unconscious and Conscious Gaze-Triggered Attentional Orienting: Distinguishing Innate and Acquired Components of Social Attention in Children and Adults with Autistic Traits and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Research 2024, 7, 0417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feniger-Schaal, R.; Koren-Karie, N. Moving together with you: Bodily expression of attachment. Arts Psychother. 2022, 80, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.A.; Rholes, W.S.; Eller, J.; Paetzold, R.L. Major principles of attachment theory. In Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 222–239. [Google Scholar]

- Akitake, B.; Douglas, H.M.; LaFosse, P.K.; Beiran, M.; Deveau, C.E.; O’rAwe, J.; Li, A.J.; Ryan, L.N.; Duffy, S.P.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Amplified cortical neural responses as animals learn to use novel activity patterns. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 2163–2174.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkel, S.J.; de Schotten, M.T.; Kawadler, J.M.; Dell’Acqua, F.; Danek, A.; Catani, M. The anatomy of fronto-occipital connections from early blunt dissections to contemporary tractography. Cortex 2014, 56, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, W.; Hou, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Guo, Z.; Bai, G. Decreased functional connectivity between the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and lingual gyrus in Alzheimer’s disease patients with depression. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 326, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampshire, A.; Zadel, A.; Sandrone, S.; Soreq, E.; Fineberg, N.; Bullmore, E.T.; Robbins, T.W.; Sahakian, B.J.; Chamberlain, S.R. Inhibition-related cortical hypoconnectivity as a candidate vulnerability marker for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2020, 5, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verpeut, J.L. Restoring cerebellar-dependent learning. eLife 2024, 13, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chang, H.; Abrams, D.A.; Kang, J.B.; Chen, L.; Rosenberg-Lee, M.; Menon, V. Atypical cognitive training-induced learning and brain plasticity and their relation to insistence on sameness in children with autism. eLife 2023, 12, e86035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Ahmadlou, M.; Suhai, S.; Neering, P.; de Kraker, L.; Heimel, J.A.; Levelt, C.N. Thalamic regulation of ocular dominance plasticity in adult visual cortex. eLife 2023, 12, RP88124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Ke, M. Altered effective connectivity of the human default mode network. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Biomedical and Intelligent Systems (IC-BIS 2023), Xiamen, China, 28 August 2023; Volume 12724, pp. 44–497. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Xu, H.; Ellenbroek, B.; Dai, J.; Wang, L.; Yan, C.; Wang, W. The Changes of Histone Methylation Induced by Adolescent Social Stress Regulate the Resting-State Activity in mPFC. Research 2023, 6, 0264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conci, M.; Busch, N.; Rozek, R.P.; Müller, H.J. Learning-Induced Plasticity Enhances the Capacity of Visual Working Memory. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 34, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz-Kraus, T.; Woodburn, M.; Rajagopal, A.; Versace, A.L.; Kowatch, R.A.; Bertocci, M.A.; Bebko, G.; Almeida, J.R.; Perlman, S.B.; Travis, M.J.; et al. Decreased functional connectivity in the fronto-parietal network in children with mood disorders compared to children with dyslexia during rest: An fMRI study. NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 18, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coan, J.A. Adult attachment and the brain. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2010, 27, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.A. Gender differences in human–animal interactions: A review. Anthrozoös 2007, 20, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamala, E.; Bassett, D.S.; Yeo, B.; Holmes, A.J. Functional brain networks are associated with both sex and gender in children. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiot, C.; Bastian, B.; Martens, P. People and companion animals: It takes two to tango. BioScience 2016, 66, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, M.J.; Zhou, Y.; Veddum, L.; Frith, C.D.; Bliksted, V.F. Aberrant effective connectivity is associated with positive symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia. NeuroImage Clin. 2020, 28, 102444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J.; Litvak, V.; Oswal, A.; Razi, A.; Stephan, K.E.; van Wijk, B.C.; Ziegler, G.; Zeidman, P. Bayesian model reduction and empirical Bayes for group (DCM) studies. NeuroImage 2016, 128, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; Mattout, J.; Trujillo-Barreto, N.; Ashburner, J.; Penny, W. Variational free energy and the Laplace approximation. NeuroImage 2007, 34, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Glenn, A.L. Evaluating methods of correcting for multiple comparisons implemented in SPM12 in social neuroscience fMRI studies: An example from moral psychology. Soc. Neurosci. 2018, 13, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.; Enders-Slegers, M.J.; Walker, J.K. The emotional lives of companion animals: Attachment and subjective claims by owners of cats and dogs. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, W.D. Comparing dynamic causal models using AIC, BIC and free energy. NeuroImage 2012, 59, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigoux, L.; Stephan, K.E.; Friston, K.J.; Daunizeau, J. Bayesian model selection for group studies—Revisited. NeuroImage 2014, 84, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Su, Q.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, R.; Yin, G.; Qin, W.; Iannetti, G.D.; Yu, C.; Liang, M. Feedforward and feedback pathways of nociceptive and tactile processing in human somatosensory system: A study of dynamic causal modeling of fMRI data. NeuroImage 2021, 234, 117957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, K.E.; Friston, K.J. Analyzing effective connectivity with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2010, 1, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.G.; Wang, X.D.; Zuo, X.N.; Zang, Y.F. DPABI: Data processing & analysis for (resting-state) brain imaging. Neuroinformatics 2016, 14, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.; Zang, Y. DPARSF: A MATLAB toolbox for “pipeline” data analysis of resting-state fMRI. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidman, P.; Jafarian, A.; Corbin, N.; Seghier, M.L.; Razi, A.; Price, C.J.; Friston, K.J. A guide to group effective connectivity analysis, part 1: First level analysis with DCM for fMRI. NeuroImage 2019, 200, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidman, P.; Jafarian, A.; Seghier, M.L.; Litvak, V.; Cagnan, H.; Price, C.J.; Friston, K.J. A guide to group effective connectivity analysis, part 2: Second level analysis with PEB. NeuroImage 2019, 200, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N = 40 | |

|---|---|

| Age (M ± S.D.) | 18–23 (19.6 ± 1.4) |

| Gender | |

| male | 5 |

| female | 35 |

| Breeding experience | |

| Pet Owner (PO) | 26 |

| Non-Pet Owner (NPO) | 14 |

| Categories of companion animals | |

| dog | 16 |

| cat | 12 |

| other mammals | 4 |

| reptile | 3 |

| insect | 2 |

| fish | 1 |

| Regions | Brodmann | Hemisphere | MNI Coordinates | Voxels | t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| IPL | 40 | R | 42 | −51 | 54 | 104 | 3.90705 |

| MOG | 19 | R | 33 | −84 | 36 | 84 | 4.19988 |

| SFG | 10 | L | −24 | 60 | 12 | 68 | 3.70245 |

| PCu | 7 | L | −9 | −63 | 48 | 35 | 3.47122 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Zhou, X.; Lin, J.; Lin, W. Specific Neural Mechanisms Underlying Humans’ Processing of Information Related to Companion Animals: A Comparison with Domestic Animals and Objects. Animals 2025, 15, 3162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213162

Liu H, Zhou X, Lin J, Lin W. Specific Neural Mechanisms Underlying Humans’ Processing of Information Related to Companion Animals: A Comparison with Domestic Animals and Objects. Animals. 2025; 15(21):3162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213162

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Heng, Xinqi Zhou, Jingyuan Lin, and Wuji Lin. 2025. "Specific Neural Mechanisms Underlying Humans’ Processing of Information Related to Companion Animals: A Comparison with Domestic Animals and Objects" Animals 15, no. 21: 3162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213162

APA StyleLiu, H., Zhou, X., Lin, J., & Lin, W. (2025). Specific Neural Mechanisms Underlying Humans’ Processing of Information Related to Companion Animals: A Comparison with Domestic Animals and Objects. Animals, 15(21), 3162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213162