Family Dogs’ Sleep Macrostructure Reflects Worsened Sleep Quality When Sleeping in the Absence of Their Owners: A Non-Invasive Polysomnography Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

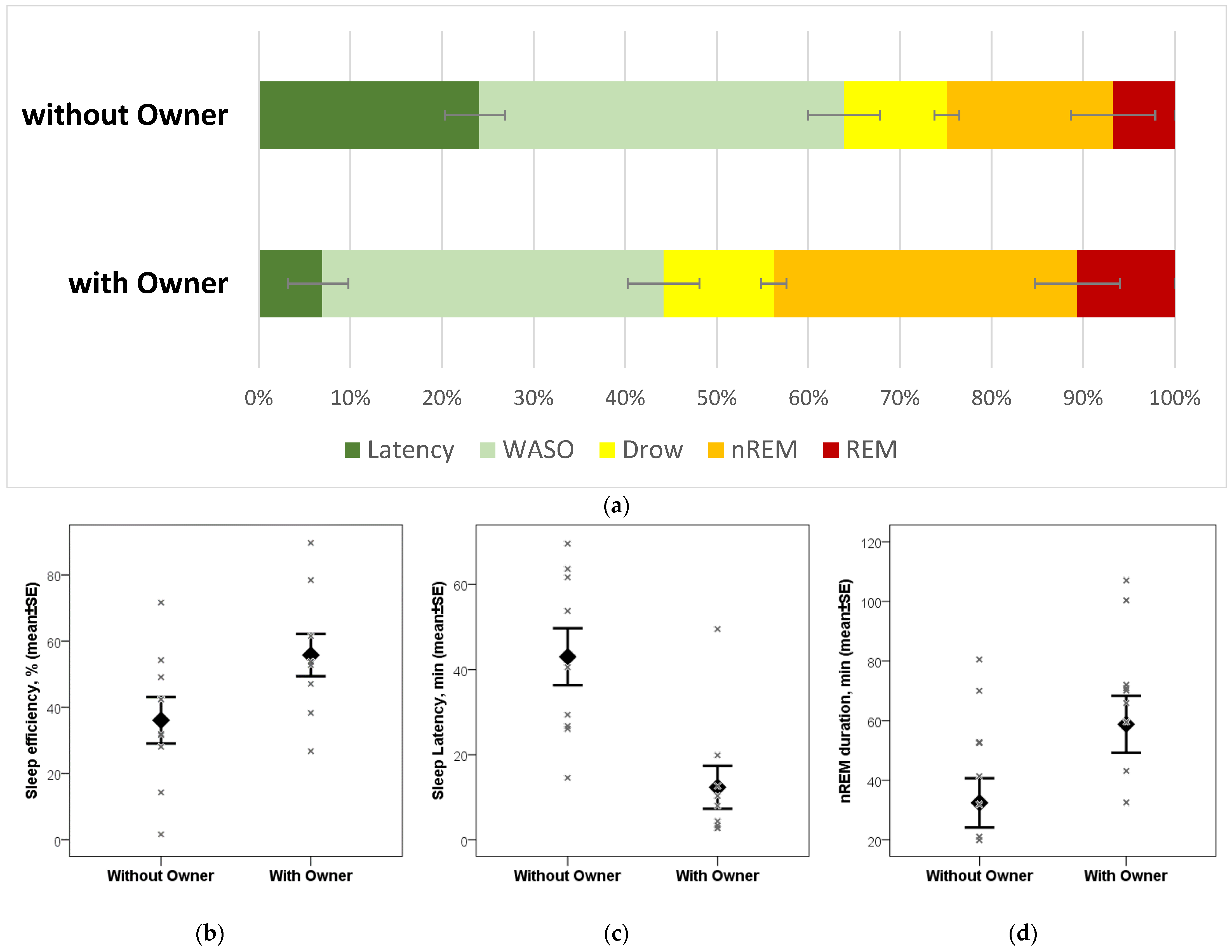

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Savolainen, P.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Luo, J.; Lundeberg, J.; Leitner, T. Genetic evidence for an East Asian origin of domestic dogs. Science 2002, 298, 1610–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gácsi, M.; Maros, K.; Sernkvist, S.; Faragó, T.; Miklósi, Á. Human analogue safe haven effect of the owner: Behavioural and heart rate response to stressful social stimuli in dogs. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topál, J.; Miklósi, Á.; Csányi, V.; Dóka, A. Attachment behavior in dogs (Canis familiaris): A new application of Ainsworth’s (1969) Strange Situation Test. J. Comp. Psychol. 1998, 112, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J.; Ainsworth, M.; Bretherton, I. The Origins of Attachment Theory. Ref. Dev. Psychol. 1992, 28, 759–775. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.S.; Bowlby, J. An ethological approach to personality development. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Wittig, B.A. Attachment and the exploratory behavior of one-year olds in a strange situation. Determ. Infant Behav. 1969, 4, 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kubinyi, E. The Link Between Companion Dogs, Human Fertility Rates, and Social Networks. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2025, 34, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubinyi, E.; Turcsán, B. From kin to canines: Understanding modern dog keeping from both biological and cultural evolutionary perspectives. Biol. Futur. 2025, 76, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, L.; Shanoyanb, A.; Aldrich, G. Assessing research needs for informing pet food industry decisions. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2024, 27, 903–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shir-Vertesh, D. ‘Flexible personhood’: Loving animals as family members in Israel. Am. Anthropol. 2012, 114, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent-Simpson, A. They make me not wanna have a child”: Effects of companion animals on fertility intentions of the childfree. Sociol. Inq. 2017, 87, 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, M. Pet Population Continues to Increase While Pet Spending Declines; AVMA: Austin, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.P.; Hazelton, P.C.; Thompson, K.R.; Trigg, J.L.; Etherton, H.C.; Blunden, S.L. A Multispecies Approach to Co-Sleeping. Hum. Nat. 2017, 28, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.P.; Browne, M.; Mack, J.; Kontou, T.G. An Exploratory Study of Human–Dog Co-sleeping Using Actigraphy: Do Dogs Disrupt Their Owner’s Sleep? Anthrozoos 2018, 31, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.L.; Browne, M.; Smith, B.P. Human-animal co-sleeping: An actigraphy-based assessment of dogs’ impacts on women’s nighttime movements. Animals 2020, 10, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.I.; Miller, B.W.; Kosiorek, H.E.; Parish, J.M.; Lyng, P.J.; Krahn, L.E. The Effect of Dogs on Human Sleep in the Home Sleep Environment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1368–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topál, J.; Gácsi, M.; Miklósi, Á.; Virányi, Z.; Kubinyi, E.; Csányi, V. Attachment to humans: A comparative study on hand-reared wolves and differently socialized dog puppies. Anim. Behav. 2005, 70, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariti, C.; Carlone, B.; Borgognini-Tarli, S.; Presciuttini, S.; Pierantoni, L.; Gazzano, A. Considering the dog as part of the system: Studying the attachment bond of dogs toward all members of the fostering family. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2011, 6, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girault, C.; Priymenko, N.; Helsly, M.; Duranton, C.; Gaunet, F. Dog behaviours in veterinary consultations: Part 1. Effect of the owner’s presence or absence. Vet. J. 2022, 280, 105788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellato, A.C.; Dewey, C.E.; Widowski, T.M.; Niel, L. Evaluation of associations between owner presence and indicators of fear in dogs during routine veterinary examinations. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2020, 257, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kis, A.; Klausz, B.; Persa, E.; Miklósi, Á.; Gácsi, M. Timing and presence of an attachment person affect sensitivity of aggression tests in shelter dogs. Vet. Rec. 2014, 174, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Meester, R.H.; Pluijmakers, J.; Vermeire, S.; Laevens, H. The use of the socially acceptable behavior test in the study of temperament of dogs. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2011, 6, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, C.; Huber, L. Obey or not obey? Dogs (Canis familiaris) behave differently in response to attentional states of their owners. J. Comp. Psychol. 2006, 120, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prato-Previde, E.; Custance, D.M.; Spiezio, C.; Sabatini, F. Is the dog–human relationship an attachment bond? An observational study using Ainsworth’ s strange situation. Behaviour 2003, 140, 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdai, J.; Miklósi, Á. Family Dog Project©: History and future of the ethological approach to human-dog interaction. Biol. Anim. Breed. 2015, 79, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lenkei, R.; Gomez, S.A.; Pongrácz, P. Fear vs. frustration—Possible factors behind canine separation related behaviour. Behav. Process. 2018, 157, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Houpt, K.A.; Scarlett, J.M. Evaluation of treatments for separation anxiety in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000, 217, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, A.; Szakadát, S.; Kovács, E.; Gácsi, M.; Simor, P.; Gombos, F.; Topál, J.; Miklósi, Á.; Bódizs, R. Development of a non-invasive polysomnography technique for dogs (Canis familiaris). Physiol. Behav. 2014, 130, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bódizs, R.; Kis, A.; Gácsi, M.; Topál, J. Sleep in the dog: Comparative, behavioral and translational relevance. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2020, 33, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotchev, I.B.; Kubinyi, E. Shared and unique features of mammalian sleep spindles—Insights from new and old animal models. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergely, A.; Kiss, O.; Reicher, V.; Iotchev, I.; Kovács, E.; Gombos, F.; Benczúr, A.; Galambos, Á.; Topál, J.; Kis, A. Reliability of family dogs’ sleep structure scoring based on manual and automated sleep stage identification. Animals 2020, 10, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, A.; Szakadát, S.; Gácsi, M.; Kovács, E.; Simor, P.; Török, C.; Gombos, F.; Bódizs, R.; Topál, J. The interrelated effect of sleep and learning in dogs (Canis familiaris); an EEG and behavioural study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolló, H.; Carreiro, C.; Iotchev, I.B.; Gombos, F.; Gácsi, M.; Topál, J.; Kis, A. The Effect of Targeted Memory Reactivation on Dogs’ Visuospatial Memory. eNeuro 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondino, A.; Gutiérrez, M.; González, C.; Mateos, D.; Torterolo, P.; Olby, N.; Delucchi, L. Electroencephalographic Signatures of Canine Cognitive Dysfunction. bioRxiv, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotchev, I.B.; Kis, A.; Bódizs, R.; Van Luijtelaar, G.; Kubinyi, E.; Van Luijtelaar, G. EEG Transients in the Sigma Range During non-REM Sleep Predict Learning in Dogs. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermándy-Berencz, K.; Kis, L.; Gombos, F.; Paulina, A.; Kis, A. Non-Invasive EEG Recordings in Epileptic Dogs (Canis familiaris). Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everest, S.; Gaitero, L.; Dony, R.; Linden, A.Z.; Cortez, M.A.; James, F.M.K. Electroencephalography: Electrode arrays in dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1402546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotchev, I.B.; Reicher, V.; Kovács, E.; Kovács, T.; Kis, A.; Gácsi, M.; Kubinyi, E. Averaging sleep spindle occurrence in dogs predicts learning performance better than single measures. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iotchev, I.B.; Szabó, D.; Turcsán, B.; Bognár, Z.; Kubinyi, E. Sleep-spindles as a marker of attention and intelligence in dogs. Neuroimage 2024, 303, 120916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreiro, C.; Reicher, V.; Kis, A.; Gácsi, M. Attachment towards the Owner Is Associated with Spontaneous Sleep EEG Parameters in Family Dogs. Animals 2022, 12, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, J.J.; Thoman, E.B.; Anders, T.F.; Sadeh, A.; Schechtman, V.L.; Glotzbach, S.F. Infant-Parent co-sleeping in an evolutionary perspective: Implications for understanding infant sleep development and the sudden infant death syndrome. Sleep 1993, 16, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, M. Comparison of neonatal nighttime sleep-wake patterns in nursery versus rooming-in environments. Nurs. Res. 1987, 36, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosko, S.; Richard, C.; McKenna, J. Infant arousals during mother-infant bed sharing: Implications for infant sleep and sudden infant death syndrome research. Pediatrics 1997, 100, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, C.A.; Mosko, S.S. Mother-infant bedsharing is associated with an increase in infant heart rate. Sleep 2004, 27, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, C.A.; Mosko, S.S.; McKenna, J.J. Apnea and periodic breathing in bed-sharing and solitary sleeping infants. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 84, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, A.; Burnham, M.M.; Goodlin-Jones, B.L.; Gaylor, E.E.; Anders, T.F. A comparison of the sleep-wake patterns of cosleeping and solitary-sleeping infants. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2004, 35, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosko, S.; Richard, C.; McKenna, J.; Drummond, S. Infant sleep architecture during bedsharing and possible implications for SIDS. Sleep 1996, 19, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilcha-Mano, S.; Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. An attachment perspective on human–pet relationships: Conceptualization and assessment of pet attachment orientations. J. Res. Pers. 2011, 45, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farle, L.; Füredi, I.V.; Pluhár, D.F.; Martos, T. Hungarian Translation of the Pet Attachment Questionnaire; University of Szeged: Szeged, Hungary, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reicher, V.; Kis, A.; Simor, P.; Bódizs, R.; Gombos, F.; Gácsi, M. Repeated afternoon sleep recordings indicate first-night-effect-like adaptation process in family dogs. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e12998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkei, R.; Carreiro, C.; Gácsi, M.; Pongrácz, P. The relationship between functional breed selection and attachment pattern in family dogs (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 235, 105231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, A.; Lenkei, R.; Fraga, P.P.; Bakos, V.; Kubinyi, E.; Faragó, T. Occurrences of non-linear phenomena and vocal harshness in dog whines as indicators of stress and ageing. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.G.; Storey, A.E.; Anderson, R.E.; Walsh, C.J. Physiological Indicators of Attachment in Domestic Dogs (Canis familiaris) and Their Owners in the Strange Situation Test. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Reite, M. Children’s responses to separation from mother during the birth of another child. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, O.; Kis, A.; Scheiling, K.; Topál, J. Behavioral and Neurophysiological Correlates of Dogs’ Individual Sensitivities to Being Observed by Their Owners While Performing a Repetitive Fetching Task. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, A.; Gergely, A.; Galambos, Á.; Abdai, J.; Gombos, F.; Bódizs, R.; Topál, J. Sleep macrostructure is modulated by positive and negative social experience in adult pet dogs. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 284, 20171883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.; Virányi, Z.; Kis, A.; Turcsán, B.; Hudecz, Á.; Marmota, M.T.; Koller, D.; Rónai, Z.; Gácsi, M.; Topál, J. Dog-owner attachment is associated with oxytocin receptor gene polymorphisms in both parties. A comparative study on Austrian and Hungarian border collies. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunford, N.; Reicher, V.; Kis, A.; Pogány, Á.; Gombos, F.; Bódizs, R.; Gácsi, M. Differences in pre-sleep activity and sleep location are associated with variability in daytime/nighttime sleep electrophysiology in the domestic dog. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotchev, I.B.; Kis, A.; Turcsán, B.; de Lara, D.R.T.F.; Reicher, V.; Kubinyi, E. Age-related differences and sexual dimorphism in canine sleep spindles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, E.; Kosztolányi, A.; Kis, A. Rapid eye movement density during REM sleep in dogs (Canis familiaris). Learn. Behav. 2018, 46, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iotchev, I.B.; Bognár, Z.; Tóth, K.; Reicher, V.; Kis, A.; Kubinyi, E. Sleep-physiological correlates of brachycephaly in dogs. Brain Struct. Funct. 2023, 228, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreiro, C.; Reicher, V.; Kis, A.; Gácsi, M. Owner-rated hyperactivity/impulsivity is associated with sleep efficiency in family dogs: A non-invasive EEG study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, I.; Hallström, I.; Söderbäck, M. Reframing the focus from a family-centred to a child-centred care approach for children’s healthcare. J. Child Health Care 2016, 20, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, L.; Tanner, A. Family centred care: A review of qualitative studies. J. Clin. Nurs. 2004, 13, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clift, L.; Dampier, S.; Timmons, S. Adolescents’ experiences of emergency admission to children’s wards. J. Child Health Care 2007, 11, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromer, L.D.; Barlow, M.R. Factors and Convergent Validity of The Pet Attachment and Life Impact Scale (PALS). Hum.-Anim. Interact. Bull. 2013, 1, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.P.; Garrity, T.F.; Stallones, L. Psychometric Evaluation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (Laps). Anthrozoos 1992, 5, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, E.; Bennett, P.C.; McGreevy, P.D. Current perspectives on attachment and bonding in the dog–human dyad. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2015, 8, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; O’brien, L.M.; Pitts, D.S.; Sagong, C.; Arnett, L.K.; Harb, N.C.; Cheng, P.; Drake, C.L. Mother-to-Infant Bonding is Associated with Maternal Insomnia, Snoring, Cognitive Arousal, and Infant Sleep Problems and Colic. Behav. Sleep Med. 2022, 20, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Teti, D.M. Infant sleeping arrangements, social criticism, and maternal distress in the first year. Infant Child Dev. 2018, 27, e2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, B.N.; Singh, T.; Carothers, A.S. Co-sleeping with pets, stress, and sleep in a nationally-representative sample of United States adults. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauglund, N.L.; Andersen, M.; Tokarska, K.; Radovanovic, T.; Kjaerby, C.; Sørensen, F.L.; Bojarowska, Z.; Untiet, V.; Ballestero, S.B.; Kolmos, M.G.; et al. Norepinephrine-mediated slow vasomotion drives glymphatic clearance during sleep. Cell 2025, 188, 606–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genzel, L.; Kroes, M.C.W.; Dresler, M.; Battaglia, F.P. Light sleep versus slow wave sleep in memory consolidation: A question of global versus local processes? Trends Neurosci. 2014, 37, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepelin, H. Mammalian sleep. In Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine; Kryger, M.H., Roth, T., Dement, W.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005; pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Guadagni, V.; Byles, H.; Hanly, P.; Younes, M.; Poulin, M. Association of sleep spindle characteristics with executive functioning in healthy sedentary middle-aged and older adults. Sleep Med. 2020, 64, S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotchev, I.B.; Szabó, D.; Kis, A.; Kubinyi, E. Possible association between spindle frequency and reversal-learning in aged family dogs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.S.; Pant, M.R.; Bommasamudram, T.; Nayak, K.R.; Roberts, S.S.H.; Gallagher, C.; Vaishali, K.; Edwards, B.J.; Tod, D.; Davis, F.; et al. Effects of sleep deprivation on physical and mental health outcomes: An umbrella review. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpers, U.M.H.; Veltman, D.J.; Van Tol, M.-J.; Kloet, R.W.; Boellaard, R.; A Lammertsma, A.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G. Neurophysiological effects of sleep deprivation in healthy adults, a pilot study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consensus Conference Panel; Watson, N.F.; Badr, M.S.; Belenky, G.; Bliwise, D.L.; Buxton, O.M.; Buysse, D.; Dinges, D.F.; Gangwisch, J.; Grandner, M.A.; et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 11, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushida, C.; Baker, T.; Dement, W.C. Electroencephalographic correlates of cataplectic attacks in narcoleptic canines. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1985, 61, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, J.C.; Kline, L.R.; Kovalski, R.J.; O’Brien, J.A.; Morrison, A.R.; Pack, A.I. The English bulldog: A natural model of sleep-disordered breathing. J. Appl. Physiol. 1987, 63, 1344–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondino, A.; Nettifee, J.; Muñana, K.R. An Exploratory Study on the Relationship Between Idiopathic Epilepsy and Sleep in Dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2025, 39, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Burman, O. Can Sleep and Resting Behaviours Be Used as Indicators of Welfare in Shelter Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris)? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejiman, T.F.; de Vries-Griever, A.H.; de Vries, G.; Meijman, T.; de Vries-Griever, A.; De Vries, G. The Evaluation of the Groningen Sleep Quality Scale; HB 88-13-EX; Heymans Bulletin: Groningen, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mondino, A.; Ludwig, C.; Menchaca, C.; Russell, K.; Simon, K.E.; Griffith, E.; Kis, A.; Lascelles, B.D.X.; Gruen, M.E.; Olby, N.J. Development and validation of a sleep questionnaire, SNoRE 3.0, to evaluate sleep in companion dogs. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baranyai, L.; Iotchev, I.; Gombos, F.; Kis, A. Family Dogs’ Sleep Macrostructure Reflects Worsened Sleep Quality When Sleeping in the Absence of Their Owners: A Non-Invasive Polysomnography Study. Animals 2025, 15, 3182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213182

Baranyai L, Iotchev I, Gombos F, Kis A. Family Dogs’ Sleep Macrostructure Reflects Worsened Sleep Quality When Sleeping in the Absence of Their Owners: A Non-Invasive Polysomnography Study. Animals. 2025; 15(21):3182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213182

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaranyai, Luca, Ivaylo Iotchev, Ferenc Gombos, and Anna Kis. 2025. "Family Dogs’ Sleep Macrostructure Reflects Worsened Sleep Quality When Sleeping in the Absence of Their Owners: A Non-Invasive Polysomnography Study" Animals 15, no. 21: 3182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213182

APA StyleBaranyai, L., Iotchev, I., Gombos, F., & Kis, A. (2025). Family Dogs’ Sleep Macrostructure Reflects Worsened Sleep Quality When Sleeping in the Absence of Their Owners: A Non-Invasive Polysomnography Study. Animals, 15(21), 3182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213182