Messaging Impacts Public Perspectives Towards Fur Farming in the Northeastern United States

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Animal Welfare Concerns

1.2. Environmental Harms

1.3. Public Health Risks

1.4. Political and Policy Responses

1.5. Consumer Attitudes and Messaging

- What are public knowledge, attitudes, perceived social norms, and beliefs toward fur products, faux fur, and fur farming in four northeastern states?

- To what extent does the public support state-level policies banning the sale of fur overall and from commercial fur farms specifically, and how does this support vary by state?

- To what extent is support for state-level bans influenced by exposure to different types of messaging (animal welfare detailing current farming harms, environmental harm, public health risk, economic arguments, faux fur alternative framing, or social norms/stigma), and do these effects differ by political affiliation, age, or identity orientation?

- What are the most important social–psychological (beliefs, attitudes, perceived norms, stigma, knowledge of harms) and demographic predictors of support for state-level fur bans?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Recruitment

2.2. Survey

2.3. Behaviors and Attitudes Toward Fur and Faux Fur

2.4. Social Norms

2.5. Knowledge

- To list two common animal species farmed for fur in the United States (open text).

- Whether most fur originates from farmed animals or from wild-trapped animals (farmed animals, wild-trapped animals, unsure).

- Whether they had seen, read, or heard about campaigns to stop the sale of fur products (yes, no, unsure).

2.6. Beliefs

2.7. Message Conditions

- Animal welfare: Described 16 categories of welfare concerns prevalent on fur farms from Warwick et al. (2023) [10], including barren housing, stress, abnormal behaviors, disease, and inhumane killing methods (e.g., electrocution).

- ○

- “A recent scientific study found that despite numerous efforts to systematically monitor and control animal welfare at fur farms, practices continue failing to meet animal welfare standards. This study found 16 categories of animal welfare concern (e.g., animals being denied access to things they need or want, stress, abnormal behaviors, unsanitary conditions, forced obesity, and high levels of sickness, disease, and death) are prevalent in fur farms. Animals are deprived of enrichment, forced to stand and rest on floors of bare wire cages, spend their entire lives in small, barren, wire-mesh cages too small for normal movement, and are deprived of contact with individuals of the same species. Further, in order to protect their fur, animals raised for fur are often killed by oral, anal, or genital electrocution.”

- Environmental: Highlighted four categories of environmental concern described in Warwick et al. (2023) [10]: greenhouse gas emissions, invasive species (15–38% originating from fur farming), water pollution from nitrogen and phosphorus runoff, and toxic chemicals (e.g., formaldehyde, chromium) used in tanning and dyeing.

- ○

- “A recent scientific study identified four main categories of environmental concern—greenhouse gas emissions, invasive species, toxic chemicals, and water quality impacts—associated with fur farming. An invasive species is a non-native mammal that reproduces quickly and causes harm to the environment, economy, and/or human health. It is estimated that between 15% and 38% of all invasive mammal species originate from fur farming. Additionally, there is a higher concentration of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) in the manure of mink compared to certain livestock. When these N and P salts are washed into water courses, aquatic plants and algae overgrow, which leads to depletion of oxygen and degradation of the ecosystem. Furthermore, fur is often tanned and dyed using toxic chemicals like formaldehyde and chromium, which can pose significant environmental and health risks, including pollution of soil and water and potential harm to workers and consumers.”

- Public health: Outlined the risk of zoonotic disease spread due to confinement and stress, citing influenza, hepatitis E, Japanese encephalitis, and at least 18 pathogens associated with fur farms (described in Warwick et al. (2023) [10]).

- ○

- “Fur farming can negatively impact public health by allowing pathogens-viruses, bacteria, or fungi that can cause disease-to spread from animals to humans. Because animals are confined in small spaces and are stressed by confinement, it makes it easier for viruses to spread. Animals on fur farms have been found to carry viruses that cause influenza as well as hepatitis E and Japanese encephalitis. A recent scientific review paper identified 18 reported endemic pathogens and diseases (e.g., Botulism, E. coli infection, avian flu) with confirmed or potential zoonotic and cross-species implications in fur farms.”

- Faux fur alternatives: Presented examples of innovative and sustainable (i.e., plant-based and recycled) faux fur alternatives (e.g., Sorona, hemp-based fibers, recycled polyester, Koba bio-based blends) increasingly used by luxury fashion brands.

- ○

- “Clothing that provides warmth and insulation that is comparable to fur from animals is widely available. Several luxury fashion designers (e.g., Stella McCartney, Gucci, Prada, and Alexander McQueen) are using faux/fake fur alternatives that have the same look and feel as fur. While alternatives to fur used to be petroleum based, faux/fake furs are now environmentally friendly and made from plant-based materials. Examples include “Sorona” (derived from corn), hemp-based faux fur, recycled polyester fibers, and innovative bio-based faux furs like “Koba” which use a blend of plant-based materials and recycled polymers, significantly reducing the environmental impact.”

- Economics: Emphasized that most fur sold in the U.S. originates from unregulated farms abroad, particularly in China and Russia, with China producing 3.5 million mink and fox pelts in 2023.

- ○

- “Consumers purchasing fur in the United States are likely not supporting US farms, but rather supporting an unregulated fur industry in countries like China and Russia. China is by far the biggest producer and consumer of fur; in 2023, China had an output of 3.5 million mink and fox pelts, followed by Poland and Russia.”

- Social norms: Shared survey data [7] showing that 73% of likely U.S. voters are concerned about fur use and over 50% support banning fur sales.

- ○

- “Because of increased knowledge on the environmental, animal welfare, and public health impacts of fur farms, the majority of the American public is concerned about the use of fur and supports policies to ban fur sales. One US national poll conducted in 2022 found that 73% of likely voters are concerned about the use of animal fur in clothing apparel and accessories like mink coats. Over 50% of likely voters would support a policy banning the sales of fur.”

2.8. Support for Fur Ban Policies

2.9. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample

3.2. Knowledge, Beliefs, and Behaviors Related to Fur, Fur Farming, and Faux Fur

3.3. Perceptions of Acceptability

3.4. Social Perceptions and Normative Beliefs

3.5. Faux Fur Attitudes and Use

- Don’t buy fake things;

- Fake fur is tacky/cheap;

- Faux fur is a good alternative;

- Don’t wear fur in general;

- Like authentic fur for longevity;

- Like how faux fur doesn’t involve killing an animal;

- Faux fur is itchy;

- Faux fur nowhere near quality of real fur;

- Faux fur less expensive.

3.6. Knowledge of Fur Farming and Animal Species Used

3.7. Beliefs About Fur and Fur Farming

3.8. Overall Support for State Policies Banning Fur

3.8.1. Control Group (No Messaging)

3.8.2. Full Sample

3.9. Impact on Voting Preferences

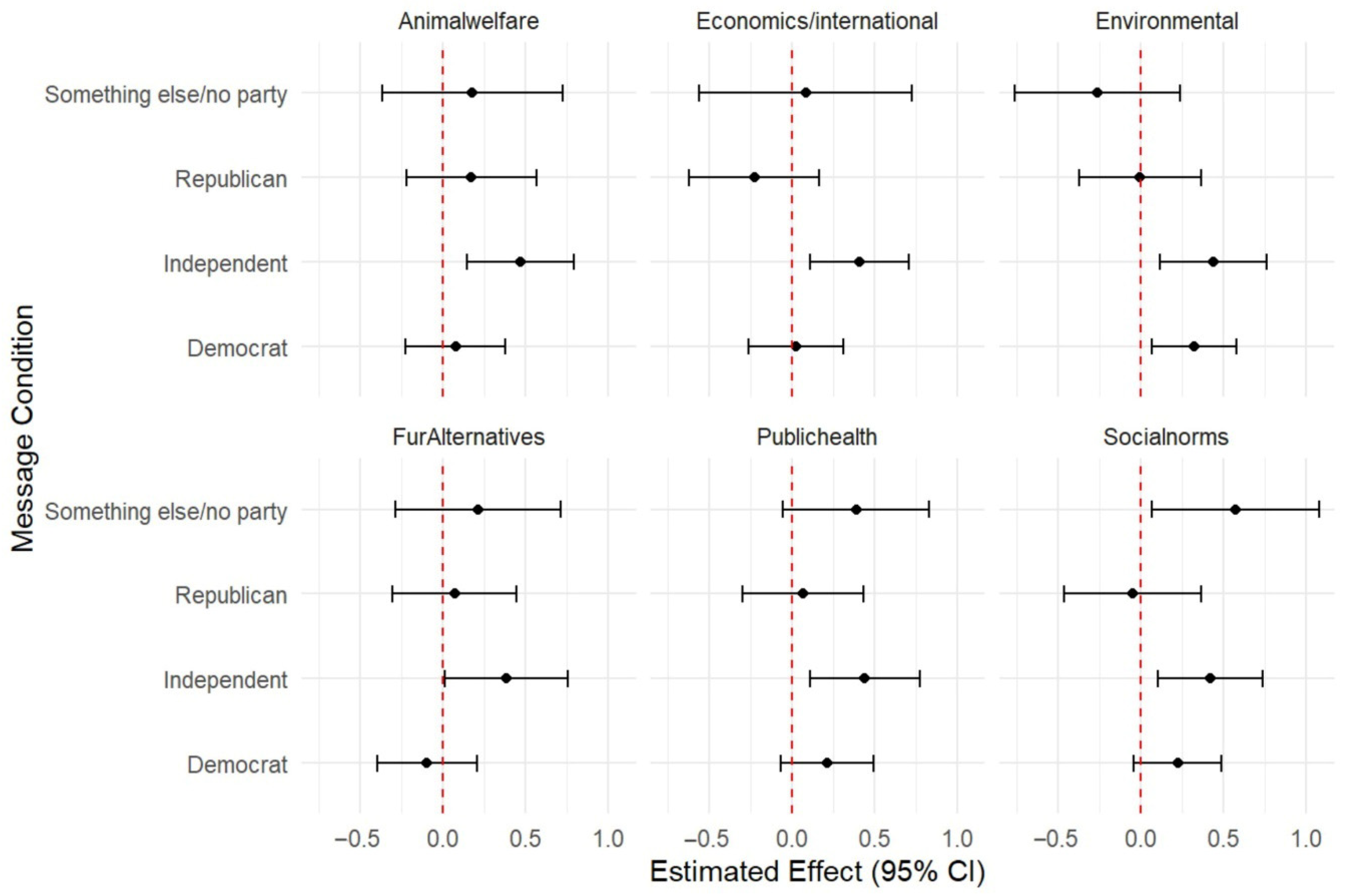

3.10. Impact of Messaging

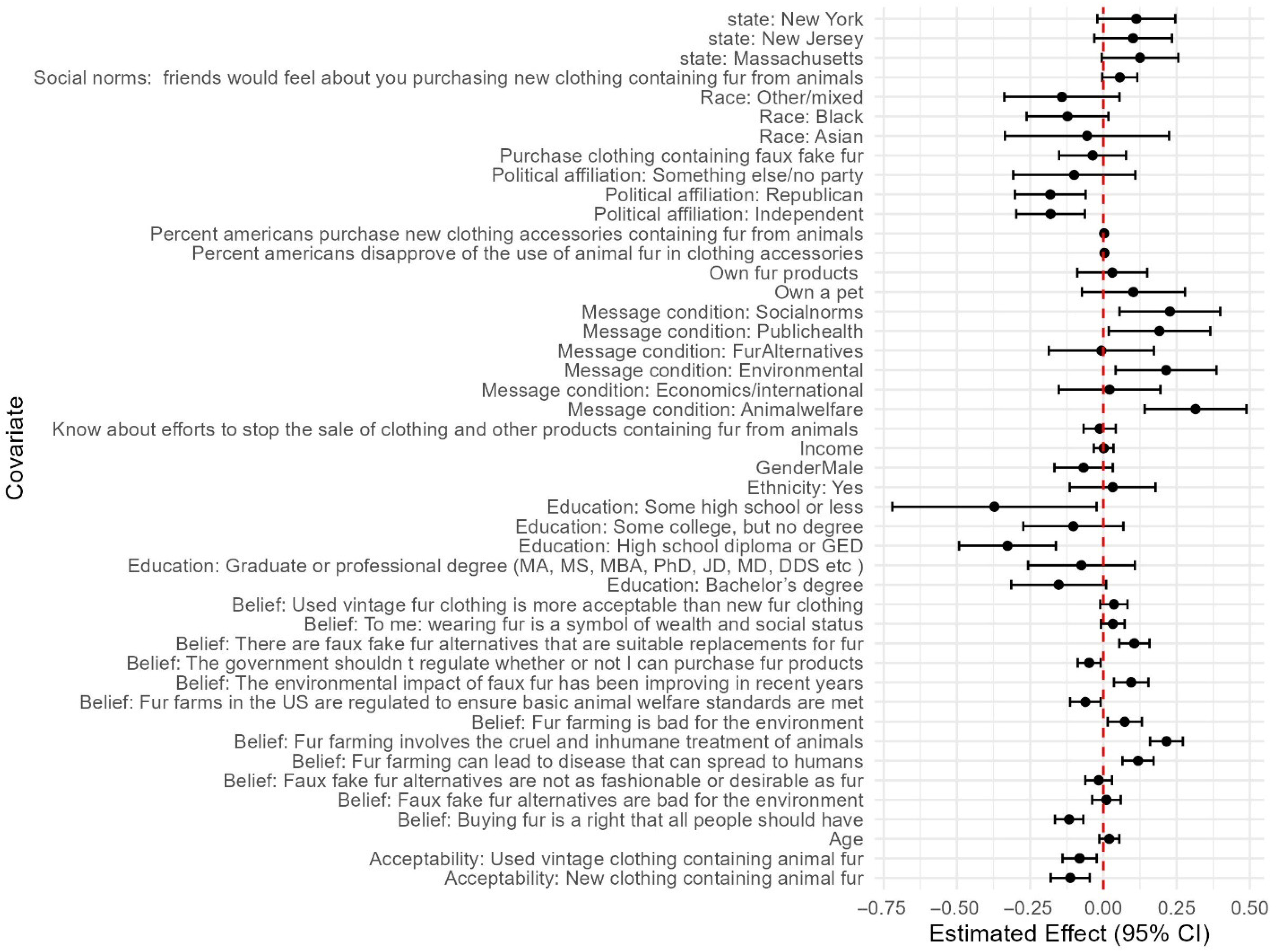

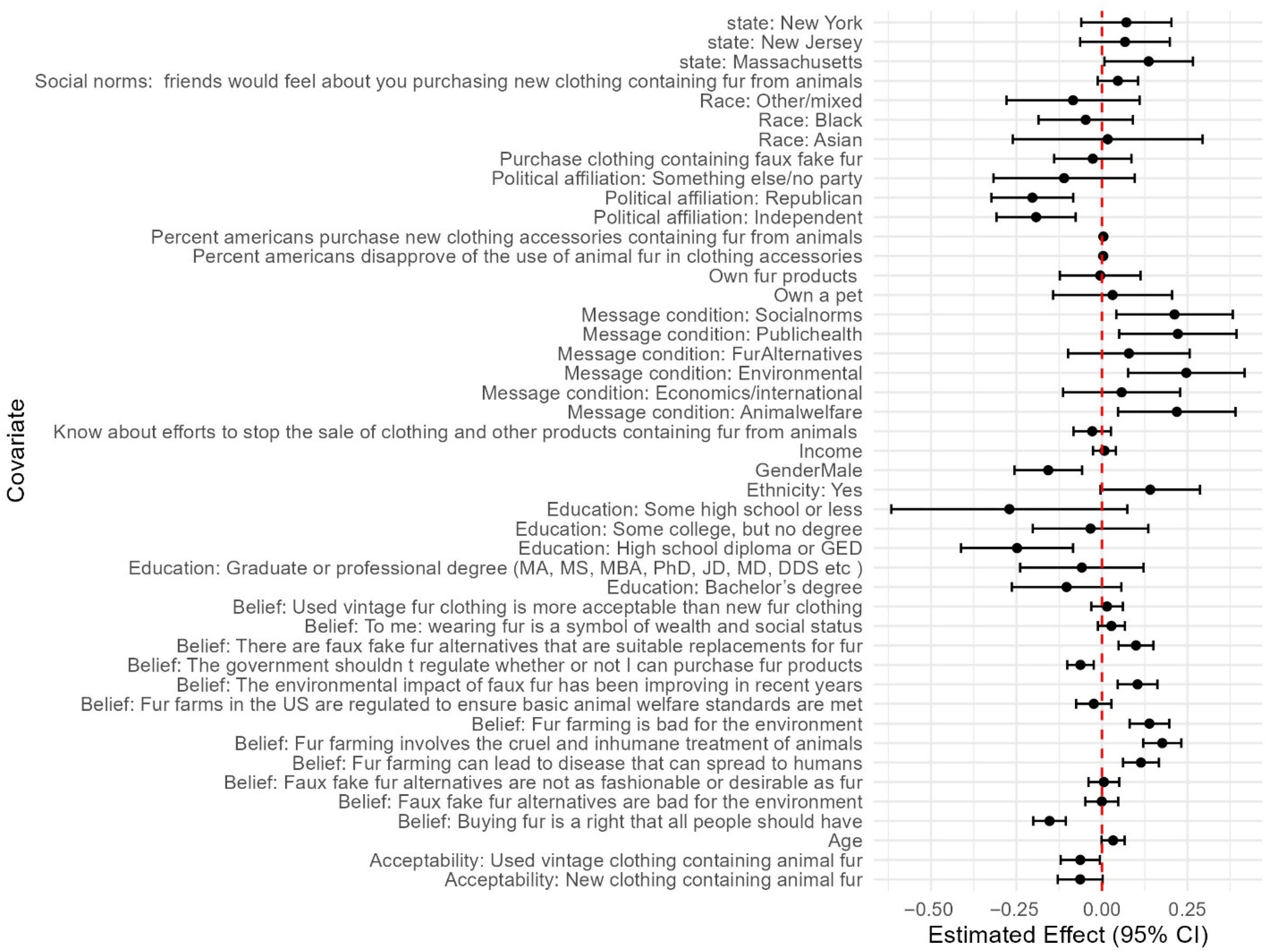

3.11. Predictors of Support

4. Discussion

4.1. Public Attitudes Toward Fur and Faux Fur

4.2. Knowledge Gaps and Misconceptions About Fur Farming

4.3. Legislative Support in Practice

4.4. The Power of Framing: Messaging Effects and Subgroup Variation

4.5. Predictors of Policy Support

4.6. Policy and Advocacy Implications

4.7. Limitations and Opportunities for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shin, D.C.; Jin, B.E. Do fur coats symbolize status or stigma? Examining the effect of perceived stigma on female consumers’ purchase intentions toward fur coats. Fash. Text. 2021, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, A.; Lewis, N.; Miller, M. Business Insider. The Rise and Fall of the Real fur Industry in the US. 2022. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/rise-and-fall-fur-industry-faux-mink-2022-2 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Bozzola, M.; Hamdan, F. Economic Decline and Ecological Impact: What Future for European Fur Farming? EuroChoices 2025, 24, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, K. Humane World for Animals. Here’s How 2024 Brought Us Closer to Ending the fur Trade for Good. 2024. Available online: https://www.humaneworld.org/en/blog/closer-to-ending-fur-trade (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Reuters. Romanian Lawmakers Vote to Phase Out fur Farming from 2027. 2024. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/romanian-lawmakers-vote-phase-out-fur-farming-2027-2024-10-22/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Halliday, C.; McCulloch, S.P. Beliefs and Attitudes of British Residents about the Welfare of Fur-Farmed Species and the Import and Sale of Fur Products in the UK. Animals 2022, 12, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broad, M. Data For Progress. National Polling Shows Fur Is Out of Fashion. 2022. Available online: https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2022/4/11/national-polling-shows-fur-is-out-of-fashion (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Hughes, A.C. Wildlife trade. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R1218–R1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW); Nielsen, S.S.; Álvarez, J.; Boklund, A.E.; Dippel, S.; Dorea, F.; Figuerola, J.; Miranda Chueca, M.Á.; Michel, V.; Nannoni, E.; et al. Welfare of American mink, red and Arctic foxes, raccoon dog and chinchilla kept for fur production. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warwick, C.; Pilny, A.; Steedman, C.; Grant, R. One health implications of fur farming. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1249901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishler, J. Fur Farming: Is It Still Legal in the United States? 2023. Available online: https://sentientmedia.org/fur-farming/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC). Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States: Chapter 43—Furskins and Artificial Fur; Manufactures Thereof; U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC): Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://hts.usitc.gov/reststop/file?release=2024HTSBasic&filename=Chapter%2043 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- United Nations Statistics Division. Trade of Goods, HS Chapter 43 Furskins and Artificial Fur; Manufactures Thereof. UN Comtrade Database. 2023. Available online: http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=ComTrade&f=_l1Code%3A44 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Karakul Sheep: Production Systems and Pelt Trade; FAO: Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/t0376e/t0376e17.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Schaumann, E. Saving sheep—On extinction narratives in Namibian Swakara farming. Camb. Prisms Extinction 2024, 2, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, K. Statista Daily Data. The World’s Biggest Fur Producers. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/33875/countries-by-number-of-fox-and-mink-pelts-produced (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- EFSA. Welfare of American Mink, Red and Arctic Foxes, Raccoon Dog and Chinchilla Kept for Fur Production. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/9519 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- FOUR PAWS International. FOUR PAWS International—Animal Welfare Organisation. EFSA Says Serious Animal Suffering Is Unavoidable on Fur Farms. 2025. Available online: https://www.four-paws.org/our-stories/press-releases/july-2025/efsa-says-serious-animal-suffering-is-unavoidable-on-fur-farms (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Fur Free Alliance. Fur Bans. Fur Free Alliance. 2025. Available online: https://www.furfreealliance.com/fur-bans/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Gregory, B.R.B.; Kissinger, J.A.; Clarkson, C.; Kimpe, L.E.; Eickmeyer, D.C.; Kurek, J.; Smol, J.P.; Blais, J.M. Are fur farms a potential source of persistent organic pollutants or mercury to nearby freshwater ecosystems? Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, J.A.; Gregory, B.R.B.; Clarkson, C.; Libera, N.; Eickmeyer, D.C.; Kimpe, L.E.; Kurek, J.; Smol, J.P.; Blais, J.M. Tracking pollution from fur farms using forensic paleolimnology. Environ. Pollut. Barking Essex 1987 2023, 335, 122307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Long, W.; Zhang, W.; Shi, B. Leaching toxicity and ecotoxicity of tanned leather waste during production phase. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 161, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACTAsia. Fur Farming Represents Significant Threat to Human and Animal Health, Linked to at Least 18 Potentially Deadly Infectious Diseases. ACTAsia. 2024. Available online: https://www.actasia.org/news/fur-farming-represents-significant-threat-to-human-and-animal-health-linked-to-at-least-18-potentially-deadly-infectious-diseases/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Fenollar, F.; Mediannikov, O.; Maurin, M.; Devaux, C.; Colson, P.; Levasseur, A.; Fournier, P.-E.; Raoult, D. Mink, SARS-CoV-2, and the Human-Animal Interface. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 663815. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.663815/full (accessed on 22 September 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oude Munnink, B.B.; Sikkema, R.S.; Nieuwenhuijse, D.F.; Molenaar, R.J.; Munger, E.; Molenkamp, R.; van der Spek, A.; Tolsma, P.; Rietveld, A.; Brouwer, M.; et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on mink farms between humans and mink and back to humans. Science 2020, 371, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomorska-Mól, M.; Włodarek, J.; Gogulski, M.; Rybska, M. Review: SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks—An overview of current knowledge on occurrence, disease and epidemiology. Animals 2021, 15, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, P.-E.; Colson, P.; Levasseur, A.; Devaux, C.A.; Gautret, P.; Bedotto, M.; Delerce, J.; Brechard, L.; Pinault, L.; Lagier, J.-C.; et al. Emergence and outcomes of the SARS-CoV-2 “Marseille-4” variant. Int. J. Infect. Dis. IJID Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2021, 106, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parth, A.-M.; Möck, M.; Vogeler, C.; Kuenzler, J. No more fashion victim? Spillovers across multiple streams: The case of fur farming bans during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy Stud. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroidis, P.C. Sealed with a Doubt: EU, Seals, and the WTO. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2015, 6, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, G.; Pabian, D. European Communities—Measures Prohibiting the Importation and Marketing of Seal Products. Am. J. Int. Law 2015, 109, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, S.P. Brexit and Animal Welfare Impact Assessment: Analysis of the Opportunities Brexit Presents for Animal Protection in the UK, EU, and Internationally. Animals 2019, 9, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olegario, M. California law changes the fashion industry furever: First Statewide Fur Ban Takes Effect This Year. SLU Law J. Online 2023, 122. Available online: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lawjournalonline/122 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Humane World for Animals. As Hundreds of Suffering Animals Are Rescued from a Midwest Fur Factory Farm, Massachusetts Legislators Seek to End Bay State’s Support for Fur Farming with Humane Bills. 2025. Available online: https://www.humaneworld.org/en/news/hundreds-suffering-animals-are-rescued-midwest-fur-factory-farm-massachusetts-legislators-seek (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Lange, K.E. Humane World for Animals. Hundreds of Animals Saved from Neglect and Cold at an Ohio Fur Farm. 2025. Available online: https://www.humaneworld.org/en/all-animals/ohio-fur-farm-rescue-400-animals (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Spellings, S. Fashion turned on fur: Young customers want more. Wall Str. J. 2025. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/style/fashion/fur-coat-vintage-prada-gucci-runway-tiktok-trend-2acd15ec?reflink=desktopwebshare_permalink (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Fur Coat. The New York Times, 2025. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/16/learning/fur-coat.html (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- The New York Times. What happened to the stigma of wearing fur? The New York Times, 2025. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/16/style/vintage-fur-trend.html (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Rolling, V.; Seifert, C.; Chattaraman, V.; Sadachar, A. Pro-environmental millennial consumers’ responses to the fur conundrum of luxury brands. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-H.; Lee, K.-H. Ethical Consumers’ Awareness of Vegan Materials: Focused on Fake Fur and Fake Leather. Sustainability 2021, 13, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Material Innovation Initiative. What Makes Fur, Fur? Material Innovation Initiative: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://materialinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/MII-What-Makes-Fur-Fur-Report-Digital.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Alevato, I.; Rissanen, T.; Lie, S. From Bio-Based to Fossil-Based to Bio-Based: Exploring the Potential of Hemp as a Material for Next-Gen Fur. Fash. Highlight 2024, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textile Exchange & Nio Fur. The Environmental Impact of Natural Fur vs. Synthetic Fur. NIO FUR. 2025. Available online: https://niofur.com/the-environmental-impact-of-natural-fur-vs-synthetic-fur/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Niemiec, R.; Jones, M.S.; Mertens, A.; Dillard, C. The effectiveness of COVID-related message framing on public beliefs and behaviors related to plant-based diets. Appetite 2021, 165, 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemiec, R.M.; Sekar, S.; Gonzalez, M.; Mertens, A. The influence of message framing on public beliefs and behaviors related to species reintroduction. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 248, 108522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grummon, A.H.; Musicus, A.A.; Salvia, M.G.; Thorndike, A.N.; Rimm, E.B. Impact of Health, Environmental, and Animal Welfare Messages Discouraging Red Meat Consumption: An Online Randomized Experiment. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 123, 466–476.e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, M.B.; Peacock, J.; Reichling, D.B.; Nadler, J.; Bain, P.A.; Gardner, C.D.; Robinson, T.N. Interventions to reduce meat consumption by appealing to animal welfare: Meta-analysis and evidence-based recommendations. Appetite 2021, 164, 105277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgerber, H. Meat-related cognitive dissonance: A conceptual framework for understanding how meat eaters reduce negative arousal from eating animals. Appetite 2020, 146, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederdeppe, J.; Shapiro, M.A.; Porticella, N. Attributions of Responsibility for Obesity: Narrative Communication Reduces Reactive Counterarguing among Liberals. Hum. Commun. Res. 2011, 37, 295–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fur Information Council of America. Economic Impact of the U.S. Fur Industry; FICA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.openphilanthropy.org/wp-content/uploads/FICA-Facts-FICA-Fur-Information-Council-of-America.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- An Act Prohibiting the Sale of Fur Products (SD.712/HD.2107); General Court of the commonwealth of Massachusetts: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://malegislature.gov/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Connecticut General Assembly. Raised Bill No. 5330: An Act Concerning the Sale of Animal Fur; Connecticut General Assembly: Hartford, CT, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.cga.ct.gov/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Stagnaro, M.N.; Druckman, J.; Berinsky, A.J.; Arechar, A.A.; Willer, R.; Rand, D. Representativeness versus response quality: Assessing nine opt-in online survey samples. OSF Prepr. 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berinsky, A.J.; Margolis, M.F.; Sances, M.W. Separating the Shirkers from the Workers? Making Sure Respondents Pay Attention on Self-Administered Surveys. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2014, 58, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, D.M.; Meyvis, T.; Davidenko, N. Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, D.; Paolacci, G.; Chandler, J. Common Concerns with MTurk as a Participant Pool: Evidence and Solutions. In Handbook of Research Methods in Consumer Psychology; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, M.; Kucker, S.C. An MTurk crisis? Shifts in data quality and the impact on study results. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 11, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballotpedia. Ballotpedia. Available online: https://ballotpedia.org/Main_Page (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Niemiec, R.M.; Champine, V.; Vaske, J.J.; Mertens, A. Does the Impact of Norms Vary by Type of Norm and Type of Conservation Behavior? A Meta-Analysis. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2020, 33, 1024–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, R.N.; Lapinski, M.K. A Re-Explication of Social Norms, Ten Years Later. Commun. Theory 2015, 25, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, M.; Rubin, D. Targeted Maximum Likelihood Learning. UC Berkeley Div. Biostat. Work. Pap. Ser. 2006, 2, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, T. Complex Surveys: A Guide to Analysis Using R; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-118-21093-2. [Google Scholar]

- American Pet Products Association. Pet Industry Market Size, Trends & Pet Industry Statistics from APPA. 2025. Available online: https://americanpetproducts.org/industry-trends-and-stats (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Mills, G. Fur farms: A ‘transmission hub’ for zoonotic viruses. Vet. Rec. 2024, 195, 230–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, T.P.; Barclay, W.S. Mink farming poses risks for future viral pandemics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2303408120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wan, W.; Yu, K.; Lemey, P.; Pettersson, J.H.-O.; Bi, Y.; Lu, M.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, M.; et al. Farmed fur animals harbour viruses with zoonotic spillover potential. Nature 2024, 634, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Gorman, J.H. The discovery of pluralistic ignorance: An ironic lesson. J. Hist. Behav. Sci. 1986, 22, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.T. A century of pluralistic ignorance: What we have learned about its origins, forms, and consequences. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, D.A.; Miller, D.T. Pluralistic Ignorance and the Perpetuation of Social Norms by Unwitting Actors. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; Volume 28, pp. 161–209. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065260108602385 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Sparkman, G.; Geiger, N.; Weber, E.U. Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Oates, C.J. What is sustainable fashion? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.; Moore, R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooman, S. Politics, Law, and Grasping the Evidence in Fur Farming: A Tale of Three Continents. In The Ethics of Fur: Religious, Cultural, and Legal Perspectives; Linzey, C., Ed.; Lexington Books: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group: Lanham, MD, USA, 2023; pp. 37–55. Available online: https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781666937947/The-Ethics-of-Fur-Religious-Cultural-and-Legal-Perspectives (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Lortie, J.; Cox, K.C.; Roundy, P.T. Social impact models, legitimacy perceptions, and consumer responses to social ventures. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reast, J.; Maon, F.; Lindgreen, A.; Vanhamme, J. Legitimacy-Seeking Organizational Strategies in Controversial Industries: A Case Study Analysis and a Bidimensional Model. Post-Print. 2013. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org//p/hal/journl/hal-00848042.html (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Bolsen, T.; Shapiro, M.A. Strategic Framing and Persuasive Messaging to Influence Climate Change Perceptions and Decisions. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science. 2017. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/climatescience/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228620-e-385 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Feinberg, M.; Willer, R. The Moral Roots of Environmental Attitudes. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumpal, I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 2025–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boas, T.C.; Christenson, D.P.; Glick, D.M. Recruiting large online samples in the United States and India: Facebook, Mechanical Turk, and Qualtrics. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 2020, 8, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J.; Richey, S.; Freed, G.L. Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e835–e842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| US Nationwide Demographics | Average Demographics Across MA, CT, NJ, and NY | Survey Sample Demographics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Bachelor’s degree or higher | 38% | 43% | 44% |

| % Household income USD 100,000 or higher | 34% | 46% | 28% |

| % 65 years old | 17% | 18% | 21% |

| % 25–34 years old | 14% | 14% | 18% |

| % Female | 51% | 51% | 53% |

| % Male | 49% | 49% | 46% |

| % Democrat * | 37% | 57% | 39% |

| % Independent * | 26% | 24% | 28% |

| % Republican * | 31% | 20% | 27% |

| % White/Caucasian | 71% | 74% | 74% |

| % Black/African American | 14% | 14% | 16% |

| Item | Overall | Connecticut | Massachusetts | New Jersey | New York |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase new clothing containing fur from animals raised on fur farms | 29.4% | 25.1% | 29.8% | 30.6% | 32.2% |

| Purchase used/vintage clothing containing fur from animals raised on fur farms | 31.5% | 27.7% | 32.2% | 34.0% | 32.3% |

| Statement | Overall | Connecticut | Massachusetts | New Jersey | New York |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Agree | % Agree | % Agree | % Agree | % Agree | |

| Wearing fur is a symbol of wealth/social status | 41.5 | 39.1 | 38.3 | 44.2 | 44.2 |

| Buying fur is a right all people should have | 42.0 | 39.1 | 41.5 | 45.0 | 42.4 |

| Faux/fake fur is bad for the environment | 26.3 | 22.5 | 26.6 | 25.8 | 30.4 |

| Faux/fake fur is less fashionable/desirable | 31.8 | 27.5 | 32.1 | 31.4 | 36.3 |

| Used/vintage fur is more acceptable than new fur | 43.6 | 42.5 | 46.0 | 44.4 | 41.7 |

| The environmental impact of faux fur has improved | 37.5 | 34.4 | 37.1 | 40.0 | 38.7 |

| Fur farming can spread disease to humans | 35.6 | 32.2 | 35.5 | 37.0 | 37.7 |

| Faux/fake fur can suitably replace real fur | 62.2 | 61.1 | 61.7 | 65.2 | 61.1 |

| Gov’t shouldn’t regulate fur purchases | 43.3 | 40.3 | 47.2 | 42.6 | 42.9 |

| Fur farming is bad for the environment | 41.3 | 42.9 | 40.5 | 42.2 | 39.7 |

| Fur farming is cruel/inhumane to animals | 60.7 | 64.2 | 59.7 | 62.4 | 56.5 |

| U.S. fur farms are regulated for welfare standards | 39.8 | 34.2 | 38.3 | 42.6 | 44.2 |

| Message Condition | ATE | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | 0.228 | 0.057 | 0.397 | 0.000 |

| Animal welfare | 0.256 | 0.078 | 0.434 | 0.005 |

| Public health | 0.236 | 0.064 | 0.408 | 0.007 |

| Social norms | 0.253 | 0.086 | 0.419 | 0.003 |

| Economics/international | 0.046 | –0.123 | 0.216 | 0.593 |

| Fur alternatives | 0.101 | –0.083 | 0.286 | 0.280 |

| Message Condition | ATE | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | 0.227 | 0.057 | 0.397 | 0.009 |

| Animal welfare | 0.256 | 0.078 | 0.434 | 0.005 |

| Public health | 0.236 | 0.064 | 0.408 | 0.007 |

| Social norms | 0.252 | 0.086 | 0.419 | 0.003 |

| Economics/international | 0.046 | –0.123 | 0.216 | 0.593 |

| Fur alternatives | 0.101 | –0.083 | 0.286 | 0.280 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kogan, L.R.; Niemiec, R.; Mertens, A. Messaging Impacts Public Perspectives Towards Fur Farming in the Northeastern United States. Animals 2025, 15, 3158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213158

Kogan LR, Niemiec R, Mertens A. Messaging Impacts Public Perspectives Towards Fur Farming in the Northeastern United States. Animals. 2025; 15(21):3158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213158

Chicago/Turabian StyleKogan, Lori R., Rebecca Niemiec, and Andrew Mertens. 2025. "Messaging Impacts Public Perspectives Towards Fur Farming in the Northeastern United States" Animals 15, no. 21: 3158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213158

APA StyleKogan, L. R., Niemiec, R., & Mertens, A. (2025). Messaging Impacts Public Perspectives Towards Fur Farming in the Northeastern United States. Animals, 15(21), 3158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213158