Climate Change and State of the Art of the Sustainable Dairy Farming: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

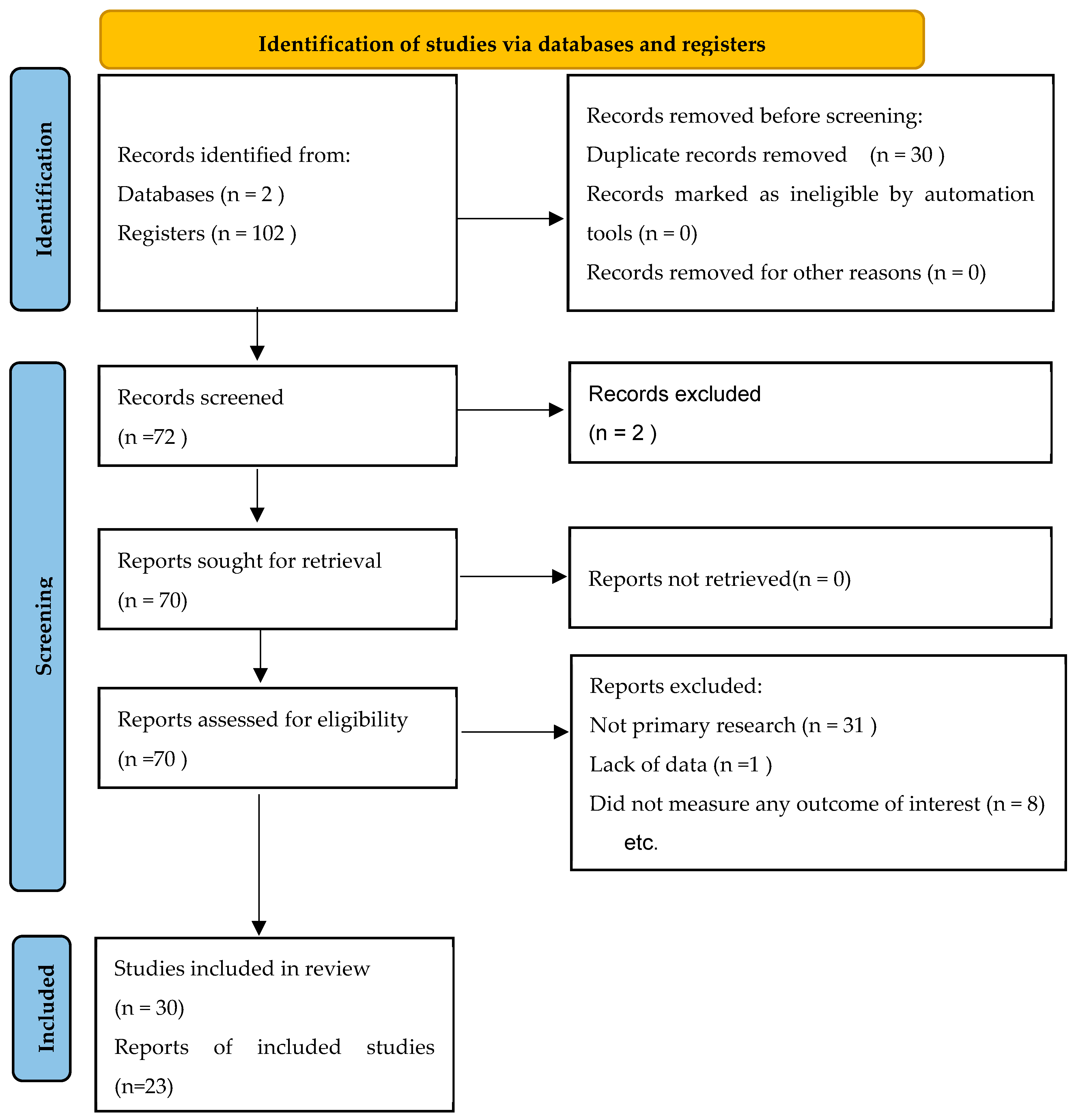

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Selection

- Climate change and heat stress in dairy cows;

- Effects of heat stress on the physiology, performance, and behavior of dairy cows;

- Climate adaptation strategies in milk production systems.

2.2. Data Extraction and Processing

3. Results

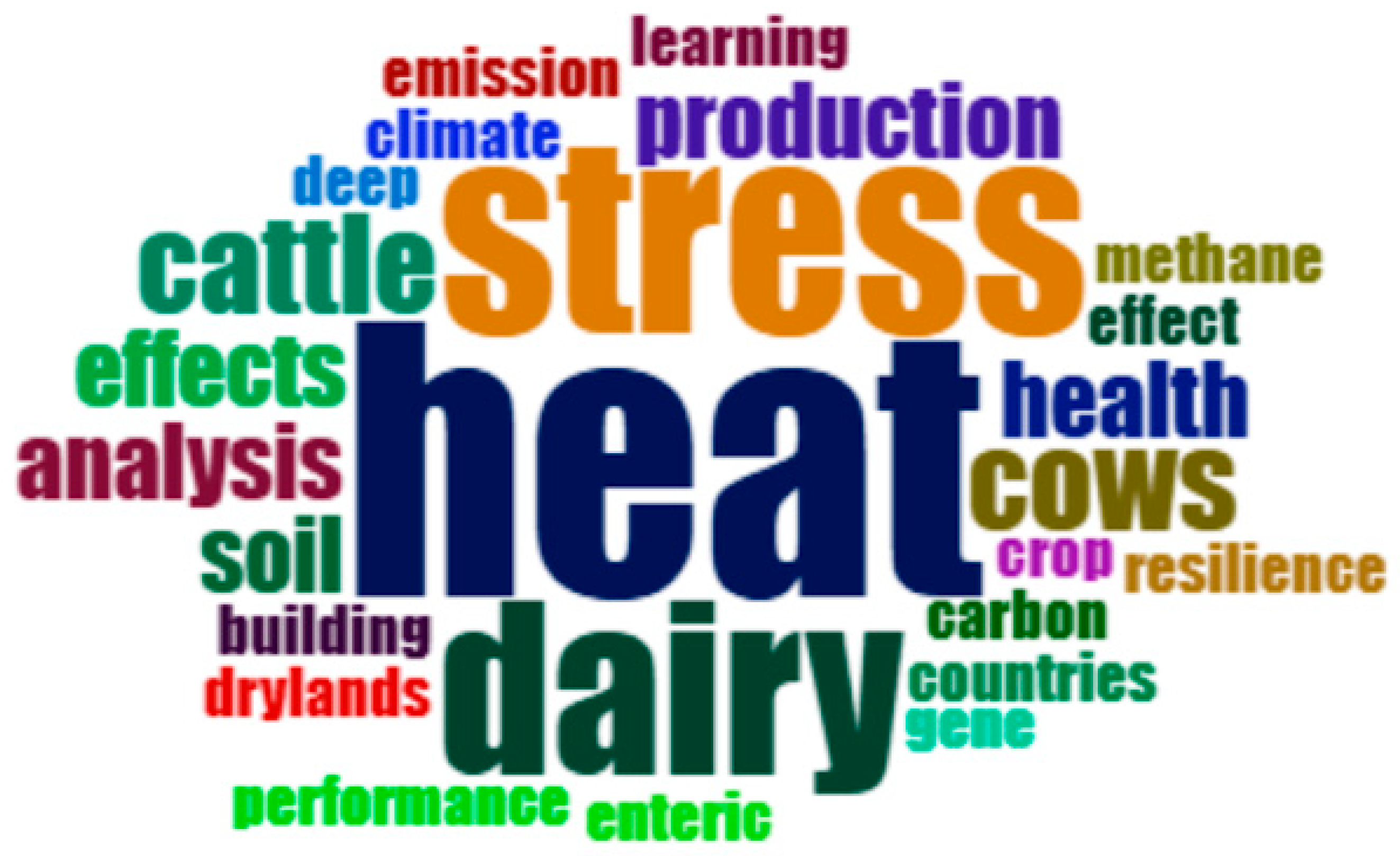

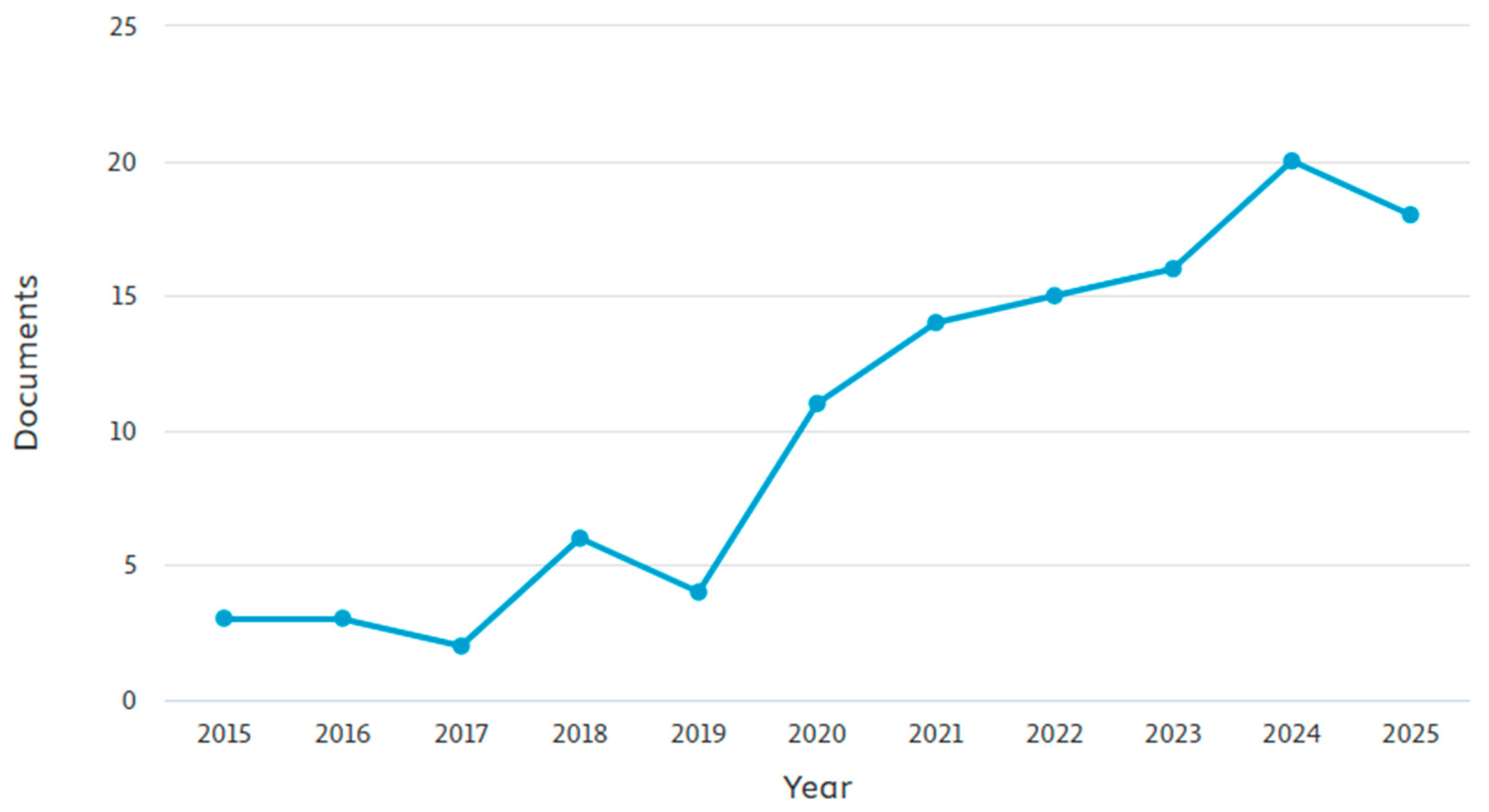

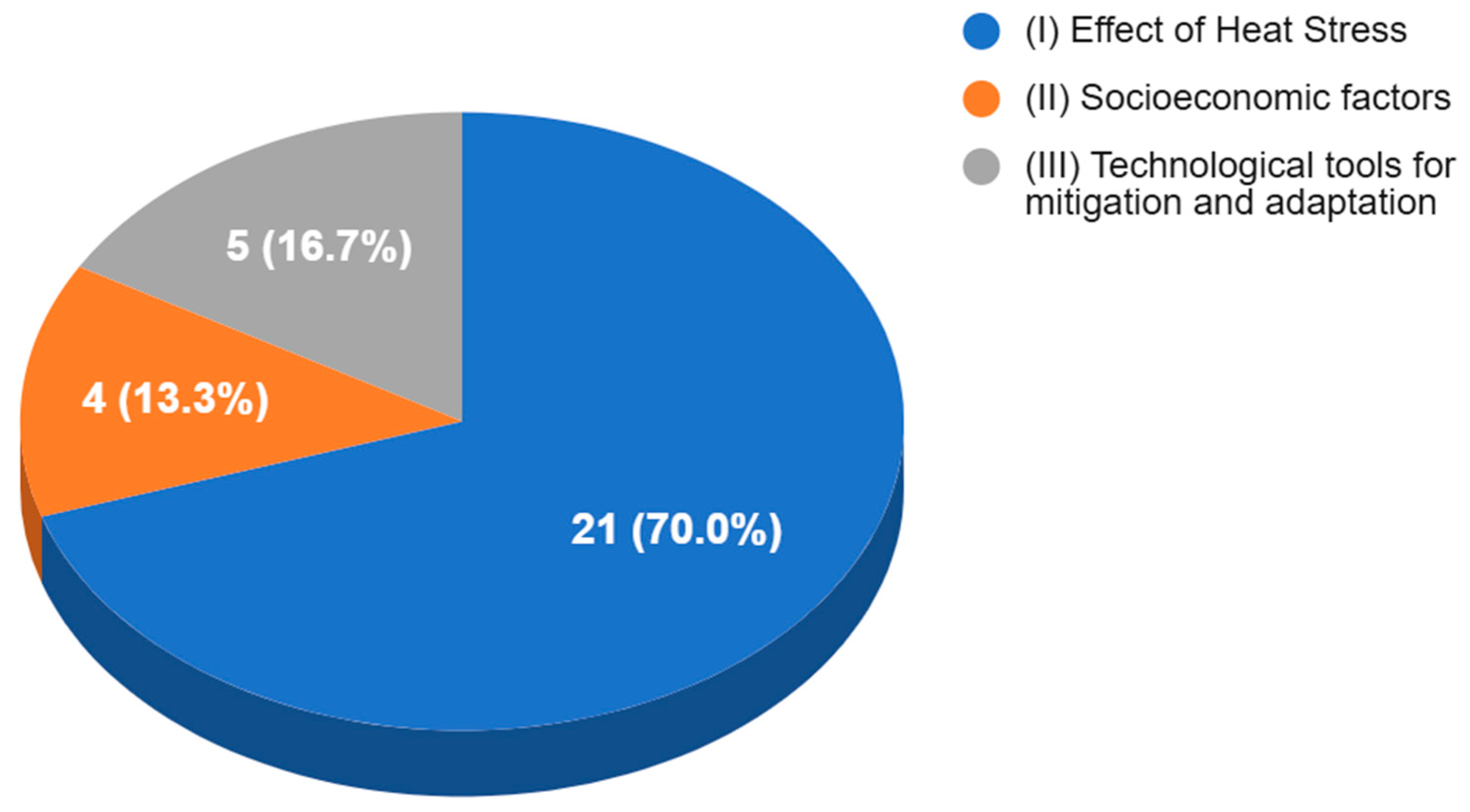

3.1. General Overview of Studies

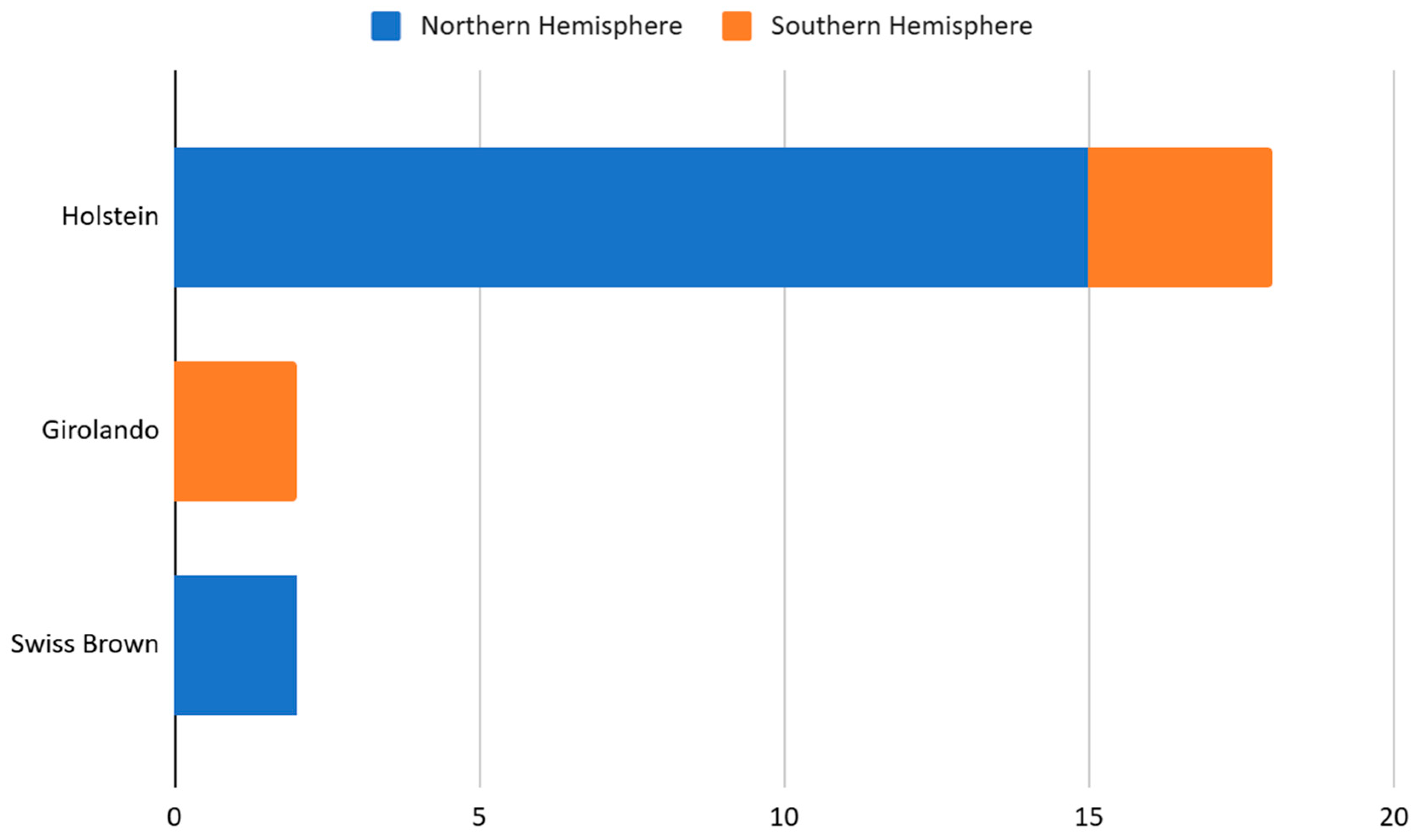

3.2. Animals and Animal Thermal Comfort Indices

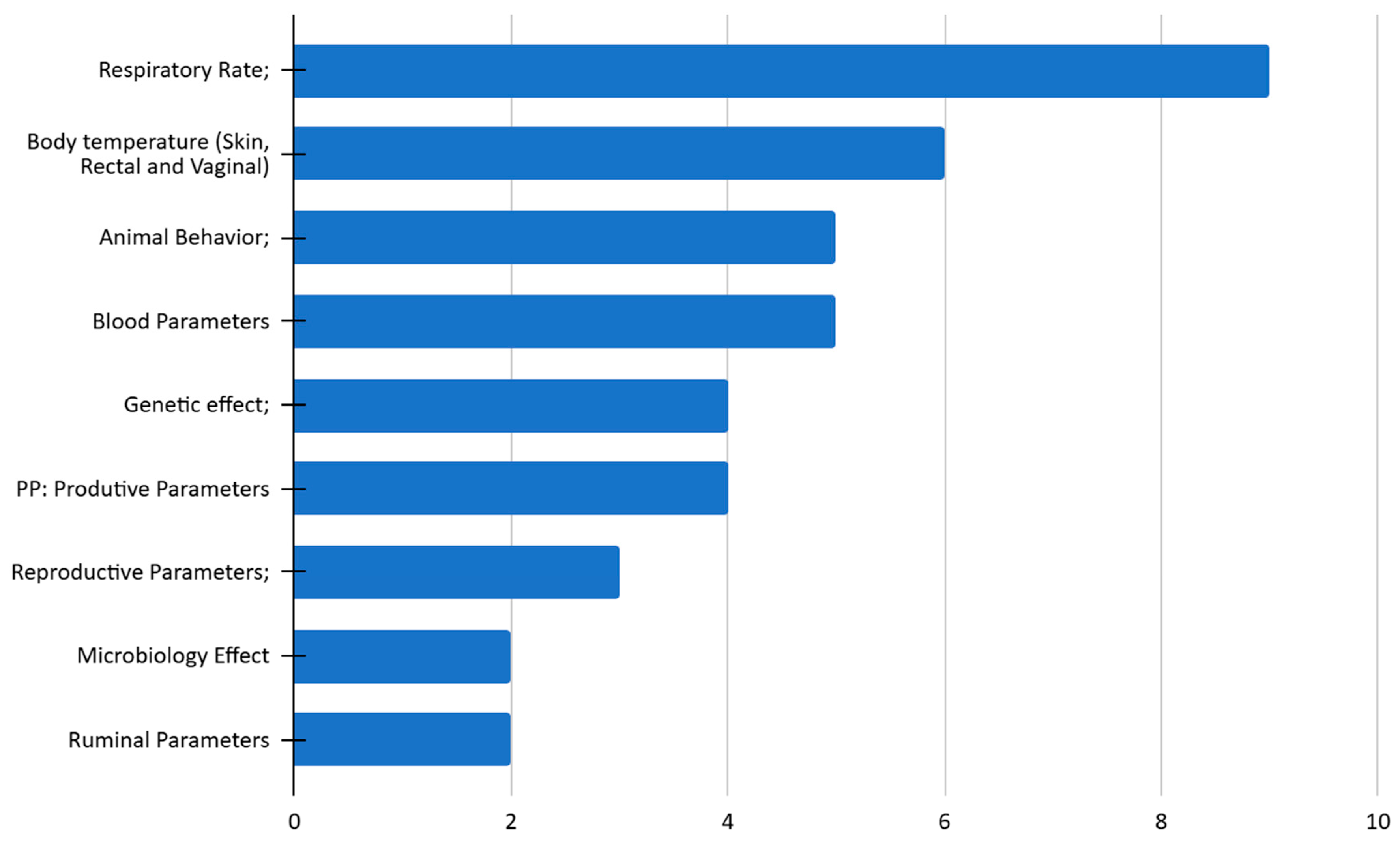

3.3. Guiding Parameters of Heat Stress

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Distribution and Socioeconomic Factors of Milk

4.2. Thermal Comfort Indices and Responses

4.3. Climate-Smart Agriculture Used to Increase Climate Resilience in Dairy Farming

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCI | Comprehensive Climate Index |

| ScP | Scopus |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| THI | Temperature Humility Index |

| WoS | Web of Science |

Appendix A

| Author | Inclusion Local |

|---|---|

| [48] | Discussion |

| [57] | Discussion |

| [56] | Discussion |

| [7] | Introduction |

| [9] | Introduction |

| [49] | Discussion |

| [5] | Introduction |

| [55] | Discussion |

| [3] | Introduction |

| [4] | Introduction |

| [8] | Introduction |

| [47] | Discussion |

| [2] | Introduction |

| [51] | Discussion |

| [54] | Discussion |

| [11] | Methodology |

| [12] | Methodology |

| [52] | Discussion |

| [53] | Discussion |

| [10] | Methodology |

| [46] | Discussion |

| [50] | Discussion |

| [1] | Introduction |

References

- Silveira, R.M.F.; Façanha, D.A.E.; de Vasconcelos, A.M.; Leite, S.C.B.; Leite, J.H.G.M.; Saraiva, E.P.; Fávero, L.P.; Tedeschi, L.O.; da Silva, I.J.O. Physiological adaptability of livestock to climate change: A global model-based assessment for the 21st century. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 116, 108061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, C.; Pimentel, F.; Ferraz, J.B.S.; Núñez-Domínguez, R.; Guimarães, R.F.; Pimentel, D.; da Gama, L.T.; Costa, N.d.S.; Peripolli, V. Mapping the composite cattle worldwide using bibliometric analysis. Livest. Sci. 2024, 290, 105593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, S.; Menz, C.; Pinto, S.; Galán, E.; Janke, D.; Estelles, F.; Müschner-Siemens, T.; Wang, X.; Heinicke, J.; Zhang, G.; et al. Heat stress risk in European dairy cattle husbandry under different climate change scenarios—Uncertainties and potential impacts. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2019, 10, 859–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, J.; Skidmore, M.; Nolan, D. Vulnerability of US dairy farms to extreme heat. Food Policy 2025, 131, 102821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Luna, P.; Mauricio-Iglesias, M.; Flysjö, A.; Hospido, A. Analysing the interaction between the dairy sector and climate change from a life cycle perspective: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 126, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Thorup, V.M.; Østergaard, S. Modeling the effects of heat stress on production and enteric methane emission in high-yielding dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 3956–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erasmus, L.M.; van Marle-Köster, E. Heat stress in dairy cows: A review of abiotic and biotic factors, with reference to the subtropics. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 55, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Fact-Checking Network Dairy Research Network (IFCN). Out Now: IFCN Dairy Report 2024: Improved Global Milk Production Growth and Recovery in Demand in 2023. 2024. Available online: https://ifcndairy.org/improved-global-milk-production-growth-recovery-in-demand-in-2023/ (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO). Milk Production|Gateway to Dairy Production and Products. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/dairy-production-products/production/milk-production/en (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, 2020th ed.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2025; p. 481. Available online: https://jira-p-us.refined.site (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Munn, Z.; Stone, J.C.; Aromataris, E.; Klugar, M.; Sears, K.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Barker, T.H. Assessing the risk of bias of quantitative analytical studies: Introducing the vision for critical appraisal within JBI systematic reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Han, J.; Bakhsh, K.; Kousar, R. Estimating impact of climate change adaptation on productivity and earnings of dairy farmers: Evidence from Pakistani Punjab. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 13017–13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amamou, H.; Beckers, Y.; Mahouachi, M.; Hammami, H. Thermotolerance indicators related to production and physiological responses to heat stress of holstein cows. J. Therm. Biol. 2019, 82, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antanaitis, R.; Džermeikaitė, K.; Krištolaitytė, J.; Ribelytė, I.; Bespalovaitė, A.; Bulvičiūtė, D.; Tolkačiovaitė, K.; Baumgartner, W. Impact of Heat Stress on the In-Line Registered Milk Fat-to-Protein Ratio and Metabolic Profile in Dairy Cows. Agriculture 2024, 14, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, R.A.; Delgado, C.; Keim, J.P.; Gandarillas, M. Use of the Comprehensive Climate Index to estimate heat stress response of grazing dairy cows in a temperate climate region. J. Dairy Res. 2021, 88, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baderha, G.K.R.; Tchoffo, R.O.K.; Ngute, A.S.K.; Imani, G.; Batumike, R.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; Cuni-Sanchez, A. Comparative Study of Climate Change Adaptation Practices in Conflict-Affected Mountain Areas of Africa. Mt. Res. Dev. 2024, 44, R20–R27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarotto, L.T.; Jones, H.N.; Chavatte-Palmer, P.; Laporta, J.; Peñagaricano, F.; Ouellet, V.; Bromfield, J.; Dahl, G. Late-gestation heat stress alters placental structure and function in multiparous dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceciliani, F.; Maggiolino, A.; Biscarini, F.; Dadi, Y.; De Matos, L.; Cremonesi, P.; Landi, V.; De Palo, P.; Lecchi, C. Heat stress has divergent effects on the milk microbiota of Holstein and Brown Swiss cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 11639–11654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Shu, H.; Sun, F.; Yao, J.; Gu, X. Impact of Heat Stress on Blood, Production, and Physiological Indicators in Heat-Tolerant and Heat-Sensitive Dairy Cows. Animals 2023, 13, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazzin, M.; Romanzin, A.; Foletto, V.; Fabro, C.; Borso, D.; Baldini, M.; Bovolenta, S.; Piasentier, E. Heat stress and feeding behaviour of dairy cows in late lactation. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresci, R.; Balkan, B.A.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Cannas, A.; Atzori, A.S. A system dynamics approach to model heat stress accumulation in dairy cows during a heatwave event. Animal 2023, 17, 101042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebrehiwot, M.; Kebede, B.; Meaza, H.; Hailu, T.; Assefa, K.; Demissie, B. Smallholder livestock farming in the face of climate change: Challenges in the Raya Alamata district of Southern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Geo Geogr. Environ. 2024, 11, e00305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jo, J.H.; Lee, H.G.; Park, W.; Lee, H.K.; Park, J.E.; Shin, D. Inflammatory response in dairy cows caused by heat stress and biological mechanisms for maintaining homeostasis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, G.; Uzmay, A. Determinants of dairy farmers’ likelihood of climate change adaptation in the Thrace Region of Turkey. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 9907–9928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, V.; Maggiolino, A.; Cecchinato, A.; Mota, L.F.M.; Bernabucci, U.; Rossoni, A.; De Palo, P. Genotype by environment interaction due to heat stress in Brown Swiss cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 1889–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leliveld, L.M.C.; Lovarelli, D.; Riva, E.; Provolo, G. Dairy cow behaviour and physical activity as indicators of heat stress. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ju, R.; Liu, C.; Tao, X.; Song, J. Investigating the potential of geothermal heat pump and precision air supply system for heat stress abatement in dairy cattle barns. J. Therm. Biol. 2025, 127, 104039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cao, Y.; Luo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Reynolds, C.K.; Humphries, D.; Zhang, C.; Codling, E.A.; Chopra, K.; Amory, J.; et al. Heat stress monitoring, modelling, and mitigation in a dairy cattle building in reading, UK: Impacts of current and projected heatwaves. Build. Environ. 2025, 279, 113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livernois, A.M.; Mallard, B.A.; Cartwright, S.L.; Canovas, A. Heat stress and immune response phenotype affect DNA methylation in blood mononuclear cells from Holstein dairy cows. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Li, X.; Hu, L.; Xu, W.; Chu, Q.; Liu, A.; Guo, G.; Liu, L.; Brito, L.F.; Wang, Y. Genomic analyses and biological validation of candidate genes for rectal temperature as an indicator of heat stress in Holstein cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 4441–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Hu, L.; Brito, L.F.; Dou, J.; Sammad, A.; Chang, Y.; Ma, L.; Guo, G.; Liu, L.; Zhai, L.; et al. Weighted single-step GWAS and RNA sequencing reveals key candidate genes associated with physiological indicators of heat stress in Holstein cattle. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonca, L.C.; Carvalho, W.A.; Campos, M.M.; Souza, G.N.; de Oliveira, S.A.; Meringhe, G.K.F.; Negrao, J. Heat stress affects milk yield, milk quality, and gene expression profiles in mammary cells of Girolando cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menta, P.R.; Machado, V.S.; Piñeiro, J.M.; Thatcher, W.W.; Santos, J.E.P.; Vieira-Neto, A. Heat stress during the transition period is associated with impaired production, reproduction, and survival in dairy 1cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 4474–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, R.; Daltro, D.; Kluska, S.; Otto, P.I.; Machado, M.A.; Panetto, J.C.D.C.; Martins, M.F.; de Oliveira, H.R.; Cobuci, J.A.; da Silva, M.V.G.B. Genomic-enhanced breeding values for heat stress tolerance in Girolando cattle in Brazil. Livest. Sci. 2023, 278, 105360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, S.; Goto, Y.; Huricha Onishi, H.; Kurachi, M.; Ito, A. Lying posture as a behavioural indicator of heat stress in dairy cows. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2023, 265, 105981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Amponsah, R.; Dunshea, F.R.; Leury, B.J.; Cheng, L.; Cullen, B.; Joy, A.; Abhijith, A.; Zhang, M.H.; Chauhan, S.S. Heat Stress Impacts on Lactating Cows Grazing Australian Summer Pastures on an Automatic Robotic Dairy. Animals 2020, 10, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Ma, L.; Gao, S.; Bu, D.; Yu, Z. Heat stress impacts the multi-domain ruminal microbiota and some of the functional features independent of its effect on feed intake in lactating dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Bindelle, J.; Guo, L.; Gu, X. Determining the onset of heat stress in a dairy herd based on automated behaviour recognition. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 226, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sölzer, N.; May, K.; Yin, T.; König, S. Genomic analyses of claw disorders in Holstein cows: Genetic parameters, trait associations, and genome-wide associations considering interactions of SNP and heat stress. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 8218–8236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Feng, M.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Fu, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H.; Qin, J. Herbal formula alleviates heat stress by improving physiological and biochemical attributes and modulating the rumen microbiome in dairy cows. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1558856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council (NRC). A Guide to Environmental Research on Animals; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Kibler, H.H. Thermal Effects of Various Temperature-Humidity Combinations on Holstein Cattle as Measured by Eight Physiological Responses; Research Bulletin Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station; University of Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station: Columbia, MO, USA, 1964; Volume 862, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mader, T.L.; Johnson, L.J.; Gaughan, J.B. A comprehensive index for assessing environmental stress in animals. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 2153–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thom, E.C. The Discomfort Index. Weatherwise 1959, 12, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Riche, E.L.; VanderZaag, A.C.; Burtt, S.; Lapen, D.R.; Gordon, R. Water Use and Conservation on a Free-Stall Dairy Farm. Water 2017, 9, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ma, W.; Shao, L. Strategies to mitigate the environmental footprints of meat, egg and milk production in northern China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 443, 141027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.R.; Tinôco, I.d.F.F.; Damasceno, F.A.; Oliveira, C.E.A.; Concha, M.S.; Zacaroni, O.d.F.; Bambi, G.; Barbari, M. Understanding Compost-Bedded Pack Barn Systems in Regions with a Tropical Climate: A Review of the Current State of the Art. Animals 2024, 14, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, N.C.R.; Andrade, R.R.; Ferreira, L.N. Climate change impacts on livestock in Brazil. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2024, 68, 2693–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, D.R.d.; Ximenes, C.A.K.; Schmitz, B.; Bettencourt, A.F.; Ebert, L.C.; Marchesini, T.; Carvalho, P.C.d.F.; Fischer, V. Changes in milking time modify behavior of grazing dairy cows. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 273, 106207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.J. Updating Animal Welfare Thinking: Moving beyond the “Five Freedoms” towards “A Life Worth Living”. Animals 2016, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obando Vega, F.A.; Montoya Ríos, A.P.; Osorio Saraz, J.A.; Andrade, R.R.; Damasceno, F.A.; Barbari, M. CFD Study of a Tunnel-Ventilated Compost-Bedded Pack Barn Integrating an Evaporative Pad Cooling System. Animals 2022, 12, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C.E.A.; Tinôco, I.D.F.F.; Oliveira, V.C.; Rodrigues, P.H.D.M.; Silva, L.F.D.; Damasceno, F.A.; Andrade, R.R.; Sousa, F.C.; Barbari, M.; Bambi, G. Spatial Distribution of Bedding Attributes in an Open Compost-Bedded Pack Barn System with Positive Pressure Ventilation in Brazilian Winter Conditions. Animals 2023, 13, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.; Moreira, J.M.; Ataídes, D.S.; Guimarães, R.A.M.; Loiola, J.L.; Sardinha, H.C. Efeitos do estresse térmico na produção de vacas leiteiras: Revisão. Pubvet 2016, 10, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habimana, V.; Nguluma, A.S.; Nziku, Z.C.; Ekine-Dzivenu, C.C.; Morota, G.; Mrode, R.; Chenyambuga, S.W. Heat stress effects on milk yield traits and metabolites and mitigation strategies for dairy cattle breeds reared in tropical and sub-tropical countries. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1121499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.M.; Sadiq, S.; Elias, S. Climate Change and Livestock Production in India: Effects and Mitigation Strategies. Indian J. Econ. Dev. 2016, 12, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, P.K.; Ayoob, A.; Strausz, P.; Vakayil, B.; Kumar, S.H.; Kusza, S. Climate change and dairy farming sustainability; a causal loop paradox and its mitigation scenario. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Paper | Summary of Objectives | Thematic Axis * |

|---|---|---|

| [13] | To investigate dairy farmers’ adaptability to climate risks and their effects on dairy farm productivity and income. | (II) |

| [14] | To investigate the effects of HS on production and physiological parameters of Holstein cows. | (I) |

| [15] | To investigate and quantify the impact of heat stress on the milk fat-to-protein ratio (F/P) and the metabolic profile in dairy cows. | (I) |

| [16] | To assess the effect of the summer thermal environment on physiological responses, behavior, milk production and its composition on grazing dairy cows in a temperate climate region, according to the stage of lactation. | (I) |

| [17] | To improve our understanding of the effects of violent conflict on smallholder farmers’ adaptation to climate change impacts by comparing one mountain affected by sectarian conflict and one mountain affected by political instability. | (II) |

| [18] | To investigate the impact of heat stress, trials were conducted over the summer months of 2020, 2022, and 2023 in Florida. | (I) |

| [19] | To compare (1) the performance of 2 dairy breeds, namely Holstein and Brown Swiss, subjected to HS and (2) the different effects of HS on the milk microbiota of the 2 breeds in thermal comfort conditions and HS. | (I) |

| [20] | To model the impact of heat stress on dairy production and enteric CH4 emissions by aggregating its effects on milk production, reproduction, and health. | (III) |

| [6] | To investigate the effects of heat stress (HS) on blood, production, and physiological indicators in heat-tolerant and heat-sensitive cows. | (I) |

| [21] | To investigate the effect of heat stress and a cooling system on the feeding behavior of Italian Holstein Friesian dairy cows in late lactation. | (I) |

| [22] | To (i) develop an explicit model able to capture the dynamic phenomena and system delays that fit observed MY in dairy cows under HS, and (ii) present an initial attempt to estimate the system delays characterizing the cow response to HS needed to parameterize the model and discriminate among cow tolerant and not-tolerant to HS. | (I) |

| [23] | To investigate climate extremes and their associated effects encountered by smallholder livestock farmers in the Raya Alamata district of northern Ethiopia. | (II) |

| [24] | To understand the effects of heat stress on the health of dairy cows and observing biological changes. | (I) |

| [25] | To demonstrate how dairy farmers in the Thrace region are affected by climate change; the second is to investigate the adaptation methods they use to minimize farm-level negative effects and finally, to analyze the farm and farmer specific factors that determine the likelihood of adaptation. | (II) |

| [26] | To investigate G × E for heat tolerance in Brown Swiss cattle for several production traits (milk, fat, and protein yield in kilograms; fat, protein, and cheese yield in percentage) and 2 derivate traits (fat-corrected milk and energy-corrected milk). | (I) |

| [27] | To study the effect of hot weather conditions on known and novel behavioral parameters. | (I) |

| [28] | To investigate the application of a combined geothermal heat pump with a precision air supply (GHP-PAS) system for cooling dairy cows on a dairy farm. | (III) |

| [29] | To fill the research gap by thoroughly investigating heat stress levels and mitigation solutions in a cubicle dairy housing barn and a milking parlor. | (III) |

| [30] | To identify epigenetic differences between high and low immune responder cows in response to heat stress. | (I) |

| [31] | To investigate the genetic architecture of RT by estimating genetic parameters, performing genome-wide association studies, and biologically validating potential candidate genes identified to be related to RT in Holstein cattle. | (I) |

| [32] | To identify quantitative trait loci (QTL) regions associated with three physiological indicators of heat stress response in Holstein cattle. | (I) |

| [33] | To understand the relationship between milk yield, milk quality, and the expression of genes related to milk synthesis, cell apoptosis, and immune response in mammary cells of Girolando cows. | (I) |

| [34] | To determine the association of heat stress (HS) exposure during the periparturient period with production, health, reproduction, and survival during the first 90 d postpartum in dairy cows. | (I) |

| [35] | To investigate the effect of heat stress in milk yield of Girolando cattle in tropical climate and to identify the most appropriate statistical approach for evaluation and selection for heat tolerance in different breed compositions of Girolando. | (I) |

| [36] | To evaluate the lying postures of cows (lying with the head turned back (HB) and lying with the head up and still (HS)) as behavioral indicators of countermeasures. | (I) |

| [37] | To measure the impacts of summer heat events on physiological parameters (body temperature, respiratory rate and panting scores), grazing behavior and production parameters of lactating Holstein Friesian cows managed on an Automated Robotic Dairy during Australian summer. | (I) |

| [38] | To examine the direct effect of HS on the ruminal microbiota using lactating Holstein cows that were pair-fed and housed in environmental chambers. | (I) |

| [39] | To propose a deep learning-based model for recognizing cow behaviors and to determine critical thresholds for the onset of heat stress at the herd level. | (III) |

| [40] | To understand the genomic mechanisms of the 3 claw disorders dermatitis digitalis (DD), interdigital hyperplasia (HYP), and sole ulcer (SU). | (I) |

| [41] | To investigate a self-developed herbal formula as a dietary intervention to mitigate heat stress. | (III) |

| Reference Index | Mathematical Formula | Mean | Min. | Max. | AET (Day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kibler [43] | THI = 0.4 (DB + WB) + 15 | 76.5 | 68 | 85 | 60 |

| Mader et al. [44] | CCI = AT + FRH + FWS + FSR | - | <20 °C | 37.9 °C | 16 |

| NRC [42] | THI = (1.8 × AT + 32) − [(0.55 − 0.0055 × RH) × (1.8 × AT − 26.8)] | 75 | 60 | 90 | 57 |

| Thom [45] | THI = (0.8 × AT + (RH/100) × (AT − 14.4) + 46.4) | 75.8 | 64.4 | 87.2 | 84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosa, D.R.d.; Ferreira, N.C.R.; Oliveira, C.E.A.; Moreira, A.N.H.; Battisti, R.; Casaroli, D.; Barbari, M.; Bambi, G.; Andrade, R.R. Climate Change and State of the Art of the Sustainable Dairy Farming: A Systematic Review. Animals 2025, 15, 2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15202997

Rosa DRd, Ferreira NCR, Oliveira CEA, Moreira ANH, Battisti R, Casaroli D, Barbari M, Bambi G, Andrade RR. Climate Change and State of the Art of the Sustainable Dairy Farming: A Systematic Review. Animals. 2025; 15(20):2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15202997

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosa, Delane Ribas da, Nicole Costa Resende Ferreira, Carlos Eduardo Alves Oliveira, Alisson Neves Harmyans Moreira, Rafael Battisti, Derblai Casaroli, Matteo Barbari, Gianluca Bambi, and Rafaella Resende Andrade. 2025. "Climate Change and State of the Art of the Sustainable Dairy Farming: A Systematic Review" Animals 15, no. 20: 2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15202997

APA StyleRosa, D. R. d., Ferreira, N. C. R., Oliveira, C. E. A., Moreira, A. N. H., Battisti, R., Casaroli, D., Barbari, M., Bambi, G., & Andrade, R. R. (2025). Climate Change and State of the Art of the Sustainable Dairy Farming: A Systematic Review. Animals, 15(20), 2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15202997