Autonomous Farmers Use of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicines in Pasture-Based Dairy Goat Systems

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

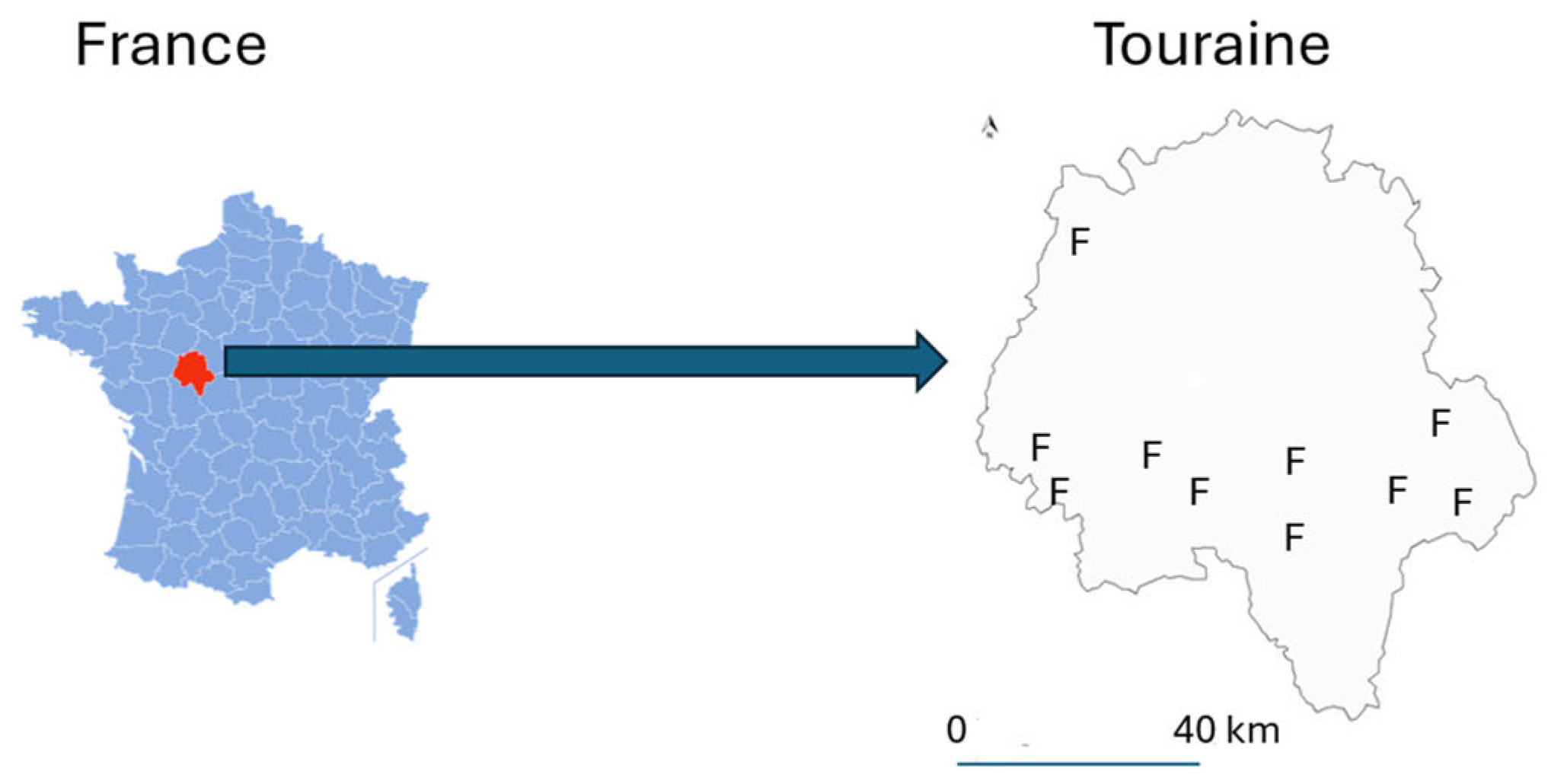

3.1. Description of Farms (Table 1)

3.2. Information from Word Occurrences for Dairy Goat Farms

3.2.1. All Dairy Goat Farms

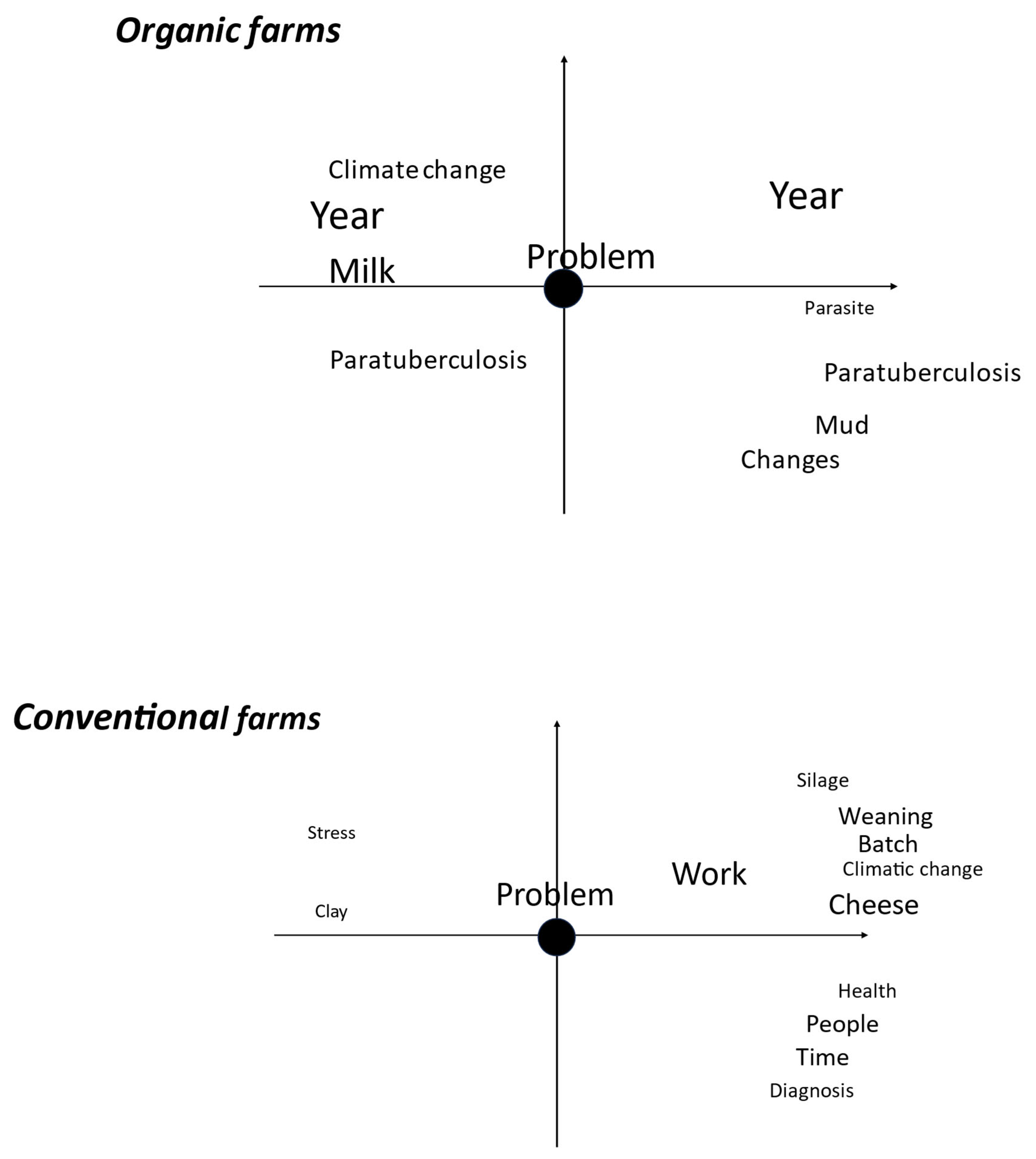

3.2.2. Differences Between Organic and Conventional Farms

3.3. Remarkable Sentences of Farmers

3.3.1. Role of Specifications Providing for Labels

3.3.2. Is CAVM Good for Animals?

3.3.3. CAVM: Coping with Societal Demand

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, J.S. Introduction: Autonomy in Healthcare. HEC Funding Statement. HEC Forum 2018, 30, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabaret, J.; Chylinski, C.; Meradi, S.; Laignel, G.; Nicourt, C.; Bentounsi, B.; Benoit, M. The trade-off between farmers’ autonomy and the control of parasitic gastro-intestinal nematodes of sheep in conventional and organic farms. Livestock Sci. 2015, 181, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaret, J.; Nicourt, C. Farmers’ and Experts’ Knowledge Coping with Sheep Health, Control and Anthelmintic Resistance of Their Gastrointestinal Nematodes. Pathogens 2024, 13, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, M.; Laignel, G. Constraints under organic farming on French sheepmeat production: A legal and economic point of view with an emphasis on farming systems and veterinary aspects. Vet. Res. 2002, 33, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ali, E.A.; Abbas, G.; Beveridge, I.; Baxendell, S.; Squire, B.; Stevenson, M.A.; Ghafar, A.; Jabbar, A. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Australian dairy goat farmers towards the control of gastrointestinal parasites. Parasites Vectors 2025, 18, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, A.; Lund, I.; Boström, A.; Hyytiäinen, H.; Asplund, K. A Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine: “Miscellaneous Therapies”. Animals 2021, 11, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiermayer, P.; Frass, M.; Peinbauer, T.; Ellinger, L.; De Beukelaer, E. Evidence-Based Human Homeopathy and Veterinary Homeopathy. Comment on Bergh et al. A Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine: “Miscellaneous Therapies” Animals 2021, 11, 3356. Animals 2022, 12, 2097. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, T.; Altaf, S.; Fatima, M.; Rasheed, R.; Laraib, K.; Azam, M.; Karamat, M.; Salma, U.; Usman, S. A narrative review on effective use of medicinal plants for the treatment of parasitic foodborne diseases. Agrobiol. Rec. 2024, 16, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyles, C. Complementary and alternative veterinary medicine. Can. Vet. J. 2020, 61, 345–346. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, M.A.; Shmalberg, J.; Adair, I.I.I.H.S.; Allweiler, S.; Bryan, J.N.; Cantwell, S.; Carr, E.; Chrisman, C.; Egger, C.M.; Greene, S.; et al. Integrative veterinary medical education and consensus guidelines for an integrative veterinary medicine curriculum within veterinary colleges. Open Vet. J. 2016, 6, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.G. Overview of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine. Merck Veterinary Manual, 11th ed. 2016. Available online: https://www.merckvetmanual.com/management-and-nutrition/complementary-and-alternative-veterinary-medicine/overview-of-complementary-and-alternative-veterinary-medicine (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Harris, P.E.; Cooper, K.L.; Relton, C.; Thomas, K.J. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: A systematic review and update. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012, 66, 924–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frass, M.; Strassl, R.P.; Friehs, H.; Müllner, M.; Kundi, M.; Kaye, A.D. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: A systematic review. Ochsner J. 2012, 12, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mallem, Y.; Prouillac, C.; Priymenko, N.; Perrot, S. Diploma of herbal medicine in the veterinary schools of France: Current state and prospects. Planta Med. 2022, 88, 1573–1574. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, B.A.; Lu, C.D. Current status of global dairy goat production: An overview. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 32, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Jaouen, J.-C.; Jénot, F. Les grandes transformations de la France rurale, de l’agriculture et de l’élevage des chèvres depuis la fin du 19è siècle. II—1960-1990: Les 30 glorieuses de la chèvre: De la marginalité à la construction d’une filière. Ethnozootechnie 2018, 105, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jénot, F.; Napoléone, M. Les grandes transformations de la France rurale, de l’agriculture et de l’élevage des chèvres depuis la fin du 19è siècle. III—L’époque actuelle depuis 1990: Double dynamique de globalisation et reterritorialisation. Ethnozootechnie 2018, 105, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Piedhault, F.; Lazard, K.; Leroux, V.; Pétrier, M.; Foisnon, B.; Lictevout, V.; Lhériau, J.-Y.; Bossis, N. Commercialisation des Fromages de Chèvre en Région. Réseaux D’élevage pour le Conseil et la Prospective; Collection Thema, Institut de l’élevage Paris: Paris, France, 2011; 43p. [Google Scholar]

- Roosen, J.; Dahlhausen, J.L.; Petershammer, S. Acceptance of Animal Husbandry Practices: The Consumer Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2016 International European Forum (151st EAAE Seminar), Innsbruck-Igls, Austria, 15–19 February 2016; pp. 260–267. [Google Scholar]

- Fontefrancesco, M.F. Modes and Forms of Knowledge of Farming Entrepreneurship: An Ethnographic Analysis among Small Farmers in NW Italy. Knowledge 2021, 1, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaret, J.; Mercier, M.; Mahieu, M.; Alexandre, G. Farmers’ Views and Tools Compared with Laboratory Evaluations of Parasites of Meat Goats in French West Indies. Animals 2023, 13, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De L’Hommeau, M. Le Traitement Phytothérapeutique Kefid’Or No 27 a-t-il un Effet Anthelminthique sur les Strongles Gastro-intestinaux? Mémoire de Brevet de Technicien Supérieur Agricole, Productions Animales; Chambre d’Agriculture d’Indre et Loire: Chambray-les-Tours, France, 2020; 33p. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R. The life story interview. In Handbook of Interview Research; Gubrium, J.F., Holstein, J.A., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK, 2002; pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hugues, E.C. The Sociological Eye: Selected Papers; Aldane: Chicago, IL, USA, 1971; 582p. [Google Scholar]

- Combessie, J.-P. L’entretien Semi-Directif. In La Méthode en Sociologie; Éditions La Découverte: Paris, France, 2007; pp. 24–32. 128p. [Google Scholar]

- Tropes, V.8. 2018. Available online: http://tropes.fr (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Ghiglione, R.; Kekenbosch, C.; Landré, A. L’Analyse Cognitive-Discursive; PUG: Grenoble, France, 1995; 142p. [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune, C. Analyser Les Contenus, Les Discours Ou Les Vécus? A Chaque Méthode Ses Logiciels! In Les Méthodes Qualitatives en Psychologie et en Sciences Humaines de la Santé; Santiago-Delafosse, M., Del Rio Carral, M., Eds.; Dunod: Malakoff, France, 2017; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- MVSP. Multivariate Statistical Package. Version 3.1. Users’ Manual; Kovach Computing Services: Wales, UK, 2001; 137p. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 2158244014522633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaba, S.; Bretagnolle, V. Social–ecological experiments to foster agroecological transition. People Nat. 2020, 2, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hivin, B. Phytothérapie et Aromathérapie en Elevage Biologique Bovin: Enquête Auprès de 271 éleveurs de France. Ph.D. Thesis, Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de Lyon, Lyon, France, 2008; 144p. [Google Scholar]

- Paolini, V.; Bergeaud, J.P.; Grisez, C.; Prevot, F.; Dorchies, P.; Hoste, H. Effects of condensed tannins on goats experimentally infected with Haemonchus contortus. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 113, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anses. Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) For Veterinary Medicinal Products. 2022. Available online: https://www.anses.fr/en/content/maximum-residue-limits-mrls-veterinary-medicinal-products (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Berkes, J.; Schröter, I.; Mergenthaler, M. Dyadic Analysis of a Speed-Dating Format between Farmers and Citizens. Societies 2022, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaret, J.; Benoit, M.; Laignel, G.; Nicourt, C. Current management of farms and internal parasites by conventional and organic meat sheep French farmers and acceptance of targeted selective treatments. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 164, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millis, D.L.; Bergh, A. A Systematic Literature Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine: Laser Therapy. Animals 2023, 13, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T. Social structure and dynamic process: The case of modern medical practice. In The Social System. Routledge Sociology Classics, New ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1991; pp. 288–322. 404p. [Google Scholar]

- Freidson, E. Profession of Medicine: A Study of the Sociology of Applied Knowledge; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988; 440p. [Google Scholar]

- Stanossek, I.; Wehrend, A. Veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine: A survey among homepages of German veterinary practitioners. Complement. Med. Res. 2023, 30, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Farm | Gender of Owner(s): Man (M) or Woman (W) | Education: Agricultural Diploma (A), Others (O), None * | Area of the Farm in ha | Number of Goats | Number of Working Units ** | Cheese Making (1) or Not (0) | Organic (1) or Not (0) | CAVM *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | M, W | A | 42 | 100 | 3.5 | 1 | 1 | Phytotherapy |

| F2 | M | A | 80 | 130 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | Phytotherapy |

| F3 | M, W | None | 80 | 125 | 3.5 | 1 | 0 | Phytotherapy |

| F4 | M, W | A | 82 | 210 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Phytotherapy, Homeopathy, Clay. |

| F5 | M, W | A | 160 | 400 | 10 | 1 | 1 | Phytotherapy, Aromatherapy, Homeopathy, Tree bark. |

| F6 | F, F | O, O | 18 | 80 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Phytotherapy Aromatherapy, Homeopathy, Clay, Vinegar. |

| F7 | M | A | 90 | 120 | 2.5 | 1 | 0 | None |

| F8 | M, W | A | 40 | 260 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Phytotherapy, Aromatherapy, Homeopathy. |

| F9 | M | A | 60 | 80 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Phytotherapy |

| F10 | M, W, W | A | 140 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Phytotherapy, Homeopathy, Osteopathy, Tree bark |

| Characteristics | Factor | Number of Occurrences |

|---|---|---|

| Temporality | Year | 55 |

| Time | 16 | |

| Animals | Herd | 24 |

| Horns | 7 | |

| Ear size | 7 | |

| Artificial insemination | 5 | |

| Farm organisation | Work | 34 |

| Organic | 28 | |

| Pasture | 19 | |

| Cereal | 17 | |

| Hectare | 14 | |

| Feed | 9 | |

| Production | Milk | 38 |

| Cheese | 30 | |

| Client and selling | 24 | |

| Health | Treatment | 37 |

| Veterinarian | 27 | |

| Mastitis | 14 | |

| Disease | 13 | |

| Foot bath | 7 | |

| Technician | 7 | |

| Parasitism | 6 | |

| Faecal egg count | 6 | |

| Disinfection | 5 | |

| Acidosis | 4 | |

| Paratuberculosis | 4 | |

| Complementary medicine | Phytotherapy | 13 |

| Aromatherapy | 7 | |

| Homeopathy | 7 | |

| Clay | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cabaret, J.; Lictevout, V. Autonomous Farmers Use of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicines in Pasture-Based Dairy Goat Systems. Animals 2025, 15, 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15111627

Cabaret J, Lictevout V. Autonomous Farmers Use of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicines in Pasture-Based Dairy Goat Systems. Animals. 2025; 15(11):1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15111627

Chicago/Turabian StyleCabaret, Jacques, and Vincent Lictevout. 2025. "Autonomous Farmers Use of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicines in Pasture-Based Dairy Goat Systems" Animals 15, no. 11: 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15111627

APA StyleCabaret, J., & Lictevout, V. (2025). Autonomous Farmers Use of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicines in Pasture-Based Dairy Goat Systems. Animals, 15(11), 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15111627