Influences of Dog Attachment and Dog Walking on Reducing Loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Benefits of Dog Walking

1.2. Dog Walking and Loneliness

1.3. Dog Walking and Attachment

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Questionnaire Design

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographics and Dog Ownership

3.2. Perception on Dog Relationships and Changes during the Pandemic Period

3.3. Perceived Outcomes of Dog Walking and Changes during the Pandemic Period

3.4. Differences of Perception by Frequency of Dog Walking

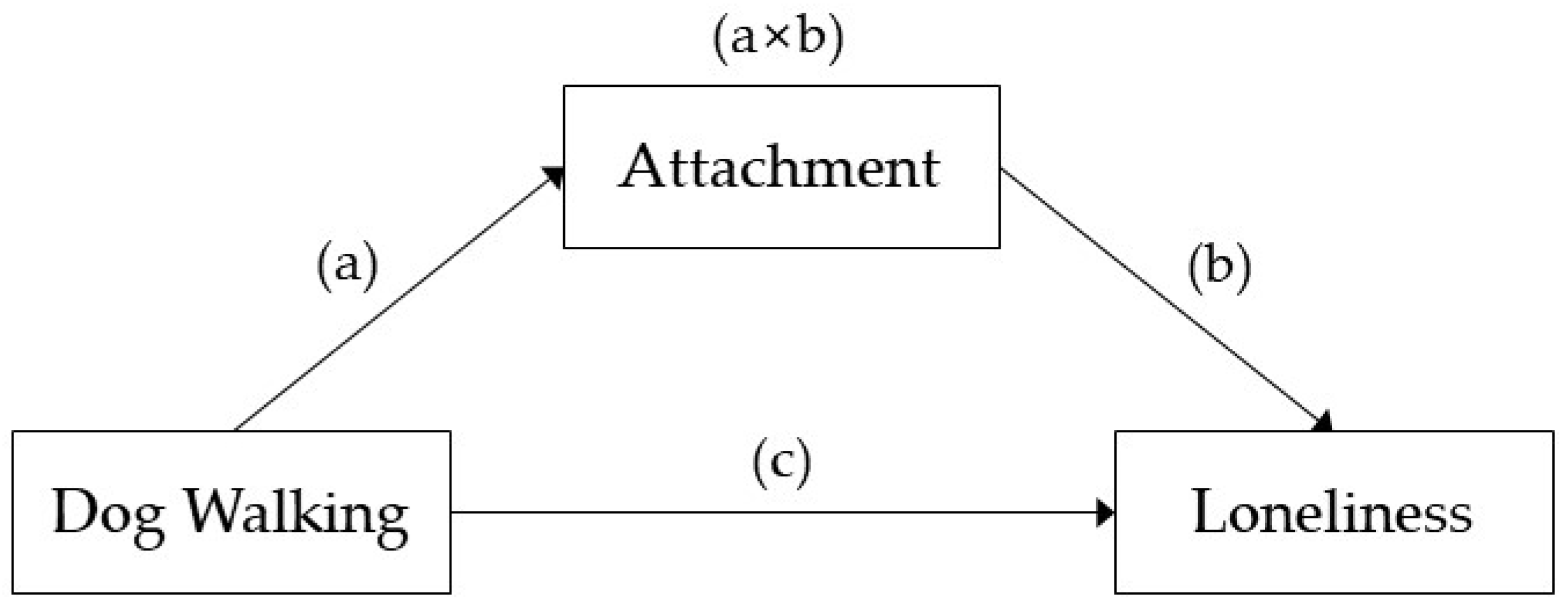

3.5. Association of Dog Walking and Loneliness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, S.M. Being Lonely at Home, This Industry Is Getting Hotter-Keep Going Even after Corona Is Over. Chosun Ilbo. 17 August 2021. Available online: https://www.chosun.com/economy/tech_it/2021/08/17/2QCMHVZJAZAEBLPXLHWQPUOPJ4/(accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. COVID-19 National Mental Health Survey. 2021. Available online: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=365582&page=1 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Morgan, L.; Protopopova, A.; Birkler, R.I.D.; Itin-Shwartz, B.; Sutton, G.A.; Gamliel, A.; Yakobson, B.; Raz, T. Human–Dog Relationships during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Booming Dog Adoption during Social Isolation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, 2020 Survey on Animal Protection. 2020. Available online: https://www.korea.kr/common/download.do?fileId=194525102&tblKey=GMN (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Lee, H.S. A Study on Perception and Needs of Urban Park Users on Off-Leash Recreation Area. KIEAE J. 2010, 10, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Jewell, C.; German, A.J.; Boddy, L.M.; Chrstian, H.E. Dog owners are more likely to meet physical activity guidelines than people without a dog: An investigation of the association between dog ownership and physical activity levels in a UK community. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Christian, H.; Bauman, A.; Epping, J.N.; Levine, G.N.; McCormack, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Richards, E.; Rock, M.; Westgarth, C. Encouraging Dog Walking for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016, 12, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Russell, S.J.; Furber, S.E.; Dobson, A.J. The Epidemiology of Dog Walking: An Unmet Need for Human and Canine Health. Med. J. Aust. 2001, 175, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisvert, J.A.; Harrell, W.A. Dog Walking: A Leisurely Solution to Pediatric and Adult Obesity? World Leis. J. 2014, 56, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Huang, P.H.; Chen, Y.L.; Hsueh, M.C.; Chang, S.H. Dog Ownership, Dog Walking, and Leisure-Time Walking among Taiwanese Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Older Adults. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thorpe, R.J.; Simonsick, E.M.; Brach, J.S.; Ayonayon, H.; Satterfield, S.; Harris, T.B.; Garcia, M.; Kritchevsky, S.B. Dog Ownership, Walking Behavior, and Maintained Mobility in Late Life. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 54, 1419–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretebeck, K.A.; Radius, K.; Black, D.R.; Gretebeck, R.J.; Ziemba, R.; Glickman, L.T. Dog Ownership, Functional Ability, and Walking in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Phys. Act. Health 2013, 10, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Youn, G.H. The Relationship between Pet Dog Ownership and Perception of Loneliness: Mediation Effects of Physical Health and Social Support. J. Inst. Soc. Sci. 2014, 25, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enmarker, I.; Hellzén, O.; Ekker, K.; Berg, A.G.T. Depression in Older Cat and Dog Owners: The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT)-3. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.M.; Pendry, P. Understanding Links Between College Students’ Childhood Pet Ownership, Attachment, and Separation Anxiety During the Transition to College. Anthrozoös 2022, 35, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.; Friedmann, E.; Gee, N.R.; Gilchrist, C.; Sachs-Ericsson, N.; Koodaly, L. Dog Walking and the Social Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Loneliness in Older Adults. Animals 2021, 11, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonacopoulos, N.M.D.; Pychyl, T.A. An Examination of the Possible Benefits for Well-Being Arising from the Social Interactions That Occur While Dog Walking. Soc. Anim. 2014, 22, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurier, E.; Maze, R.; Lundin, J. Putting the Dog Back in the Park: Animal and Human Mind-in-Action. Mind Cult. Act. 2006, 13, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, K. ‘Dog Breaks Ice’: The Sociability of Dog-Walking. In Making Links: Fifteen Visions of Community; McKeever, R., Ed.; Community Links: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy-Gerlach, J.; Rauktis, M.; Newhill, C. (Non-Human) Animal Companionship: A Crucial Support for People during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Soc. Regist. 2020, 4, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, G.; Stenvold, L.C.; Rudmin, F.W. “My Dog Is My Best Friend”: Health Benefits of Emotional Attachment to a Pet Dog. Psychol. Soc. 2013, 5, 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.G.; Rhodes, R.E. Relationships among Dog Ownership and Leisure-Time Walking in Western Canadian Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 30, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, M.J.; Hyatt, E.M. Understanding Dog–Human Companionship. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scandurra, A.; Alterisio, A.; D’Aniello, B. Behavioural Effects of Training on Water Rescue Dogs in the Strange Situation Test. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 174, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrity, T.F.; Stallones, L.F.; Marx, M.B.; Johnson, T.P. Pet Ownership and attachment as supportive factors in the health of the elderly. Anthrozoos 1989, 3, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chur-Hansen, A.; Winefield, H.R.; Beckwith, M. Companion Animals for Elderly Women: The Importance of Attachment. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2009, 6, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, E.A.; McDonough, M.H.; Edwards, N.E.; Lyle, R.M.; Troped, P.J. Development and psychometric testing of the Dogs and WalkinG Survey (DAWGS). Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2013, 84.4, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cutt, H.E.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M.W.; Pikora, T.J. Physical Activity Behavior of Dog Owners: Development and Reliability of the Dogs and Physical Activity (DAPA) Tool. J. Phys. Act. Health 2008, 5, S73–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoesmith, E.; Shahab, L.; Kale, D.; Mills, D.S.; Reeve, C.; Toner, P.; Assis, L.S.; Ratschen, E. The influence of human–animal interactions on mental and physical health during the first COVID-19 lockdown phase in the U.K.: A Qualitative Exploration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Shepley, M.; Huang, C.S. Evaluation of Off-Leash Dog Parks in Texas and Florida: A Study of Use Patterns, User Satisfaction, and Perception. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 92, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohlf, V.I.; Toukhsati, S.; Coleman, G.J.; Bennett, P.C. Dog obesity: Can dog caregivers’ (owners’) feeding and exercise intentions and behaviors be predicted from attitudes? J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2010, 13, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 207 (83.1%) |

| Male | 42 (16.9%) | |

| Age | 29 years old or less | 108 (43.4%) |

| 30 to 39 years | 94 (37.8%) | |

| 40 years old or more | 47 (18.8%) | |

| Family type | Single residence | 66 (26.5%) |

| Married couple | 48 (19.3%) | |

| Living with parents | 94 (37.8%) | |

| Living with children | 30 (12.0%) | |

| Others | 11 (4.4%) | |

| Education | High school graduate or less | 75 (30.1%) |

| College graduate | 161 (64.7%) | |

| Graduate school or higher | 13 (5.2%) | |

| Dogs living in the home | One dog | 163 (65.5%) |

| Two dogs | 61 (24.5%) | |

| Three or more dogs | 25 (10.0%) | |

| Walking frequency | Once a day or more | 119 (47.8%) |

| 4–6 times a week | 54 (21.7%) | |

| 2–3 times a week | 49 (19.7%) | |

| Once a week | 17 (6.8%) | |

| One to three times a month | 10 (4.0%) | |

| Walking time per walk | 30 min or less | 47 (18.9%) |

| More than 30 min to 1 h | 148 (59.4%) | |

| More than 1 h to 2 h | 50 (20.1%) | |

| More than 2 h | 4 (1.6%) | |

| M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dog relationship | I think of my dog(s) as a family. | 4.9 | 0.3 |

| I feel happier thanks to my dog(s). | 4.9 | 0.4 | |

| I feel less lonely thanks to my dog(s). | 4.7 | 0.6 | |

| I talk to my dog(s). | 4.7 | 0.5 | |

| My dog(s) seems to know my feelings well. | 4.1 | 0.9 | |

| I often play with my dog(s). | 4.0 | 0.8 | |

| During the pandemic, I spend more time with my dog(s). | 4.2 | 1.0 | |

| During the pandemic, I became more attached to my dog(s). | 3.9 | 1.1 |

| M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived outcomes of dog walking | I also get to do more physical activities. | 4.3 | 0.8 |

| It helps me maintain my health. | 4.1 | 0.9 | |

| It is helpful for the health of dog(s). | 4.4 | 0.7 | |

| It’s a break for me. | 4.1 | 0.9 | |

| Opportunities to talk to other people arise. | 3.7 | 1.1 | |

| If I don’t take a dog(s) walk often I feel guilty. | 4.3 | 0.8 | |

| During the pandemic, I walked my dog(s) more often. | 3.3 | 1.1 | |

| During the pandemic, I felt that there was not enough space to take a walk with my dog(s). | 3.2 | 1.1 | |

| During the pandemic, I felt the importance of the park/green area to take a walk. | 4.1 | 1.0 |

| Perception | Group | N | Mean | SD | df | t-Value | p-Value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I often play with my dog(s). | Once a day or more | 119 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 247 | 3.08 | 0.002 *** | 0.39 |

| Less than once a day | 130 | 3.8 | 0.8 | |||||

| During the pandemic period, I spend more time with my dog(s). | Once a day or more | 119 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 247 | 2.09 | 0.037 * | 0.27 |

| Less than once a day | 130 | 4.1 | 1.0 | |||||

| I also get to do more physical activities. | Once a day or more | 119 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 247 | 2.94 | 0.004 *** | 0.37 |

| Less than once a day | 130 | 4.1 | 0.8 | |||||

| It helps me maintain my health. | Once a day or more | 119 | 4.2 | 0.8 | 247 | 2.58 | 0.01 * | 0.33 |

| Less than once a day | 130 | 3.9 | 0.9 | |||||

| It is helpful for the health of dog(s). | Once a day or more | 119 | 4.5 | 0.6 | 247 | 2.58 | 0.01 * | 0.33 |

| Less than once a day | 130 | 4.3 | 0.8 | |||||

| If I don’t take a dog(s) walk often, I feel guilty. | Once a day or more | 119 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 247 | 2.51 | 0.013 * | 0.32 |

| Less than once a day | 130 | 4.2 | 0.8 | |||||

| During the pandemic period, I walked my dog(s) more often. | Once a day or more | 119 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 237 | 2.80 | 0.006 ** | 0.36 |

| Less than once a day | 130 | 3.1 | 1.1 |

| Dog Walking | Loneliness | Attachment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dog walking | 1 | ||

| Loneliness | 0.105 | 1 | |

| Attachment | 0.481 ** | 0.226 ** | 1 |

| Effect | B | SE | t | p | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 0.454 | 0.053 | 8.616 | 0.000 | 0.340 | 0.557 |

| b | 0.124 | 0.037 | 3.635 | 0.000 | - | - |

| a × b | 0.125 | 0.039 | 3.219 | 0.002 | 0.049 | 0.202 |

| c | 0.054 | 0.033 | 1.644 | 0.102 | −0.011 | 0.118 |

| Total effect | 0.054 | 0.033 | −0.082 | 0.102 | −0.011 | 0.118 |

| Direct effect (c) | −0.003 | 0.037 | 1.644 | 0.934 | −0.075 | 0.069 |

| Indirect effect (a × b) | 0.057 | 0.018 | - | - | 0.023 | 0.096 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.-S.; Song, J.-G.; Lee, J.-Y. Influences of Dog Attachment and Dog Walking on Reducing Loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea. Animals 2022, 12, 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12040483

Lee H-S, Song J-G, Lee J-Y. Influences of Dog Attachment and Dog Walking on Reducing Loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea. Animals. 2022; 12(4):483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12040483

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hyung-Sook, Jin-Gyeoung Song, and Jeong-Yeon Lee. 2022. "Influences of Dog Attachment and Dog Walking on Reducing Loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea" Animals 12, no. 4: 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12040483

APA StyleLee, H.-S., Song, J.-G., & Lee, J.-Y. (2022). Influences of Dog Attachment and Dog Walking on Reducing Loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea. Animals, 12(4), 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12040483