Tenebrio molitor Larvae Meal Affects the Cecal Microbiota of Growing Pigs

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Diets

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. RNA Extraction and qPCR Analysis

2.4. Determination of Cecal Microbiota Composition and Diversity

2.5. Determination of Concentrations of SCFA in Cecal Digesta of the Pigs

2.6. Determination of the Bile Acid Concentration in the Feces

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

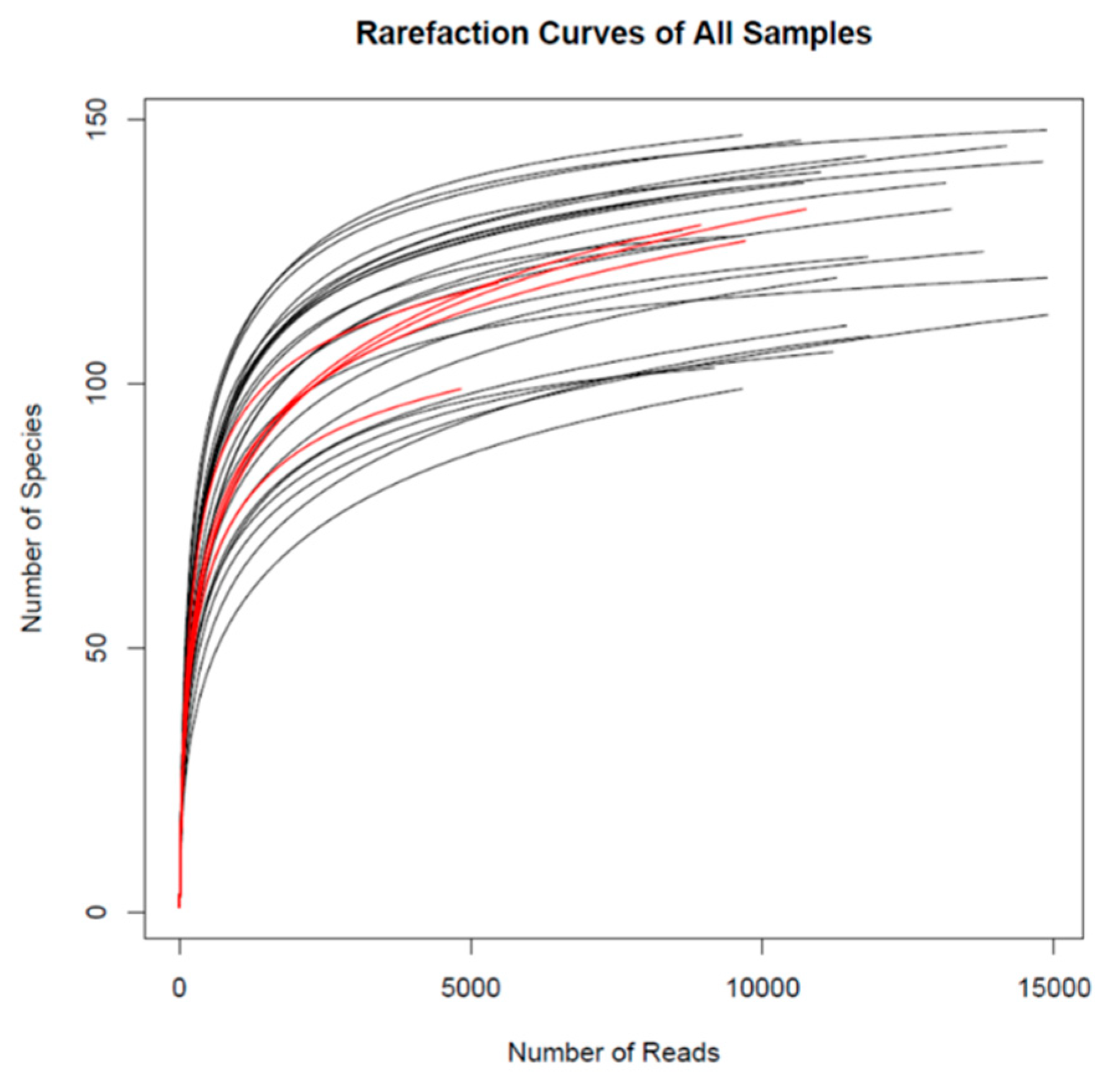

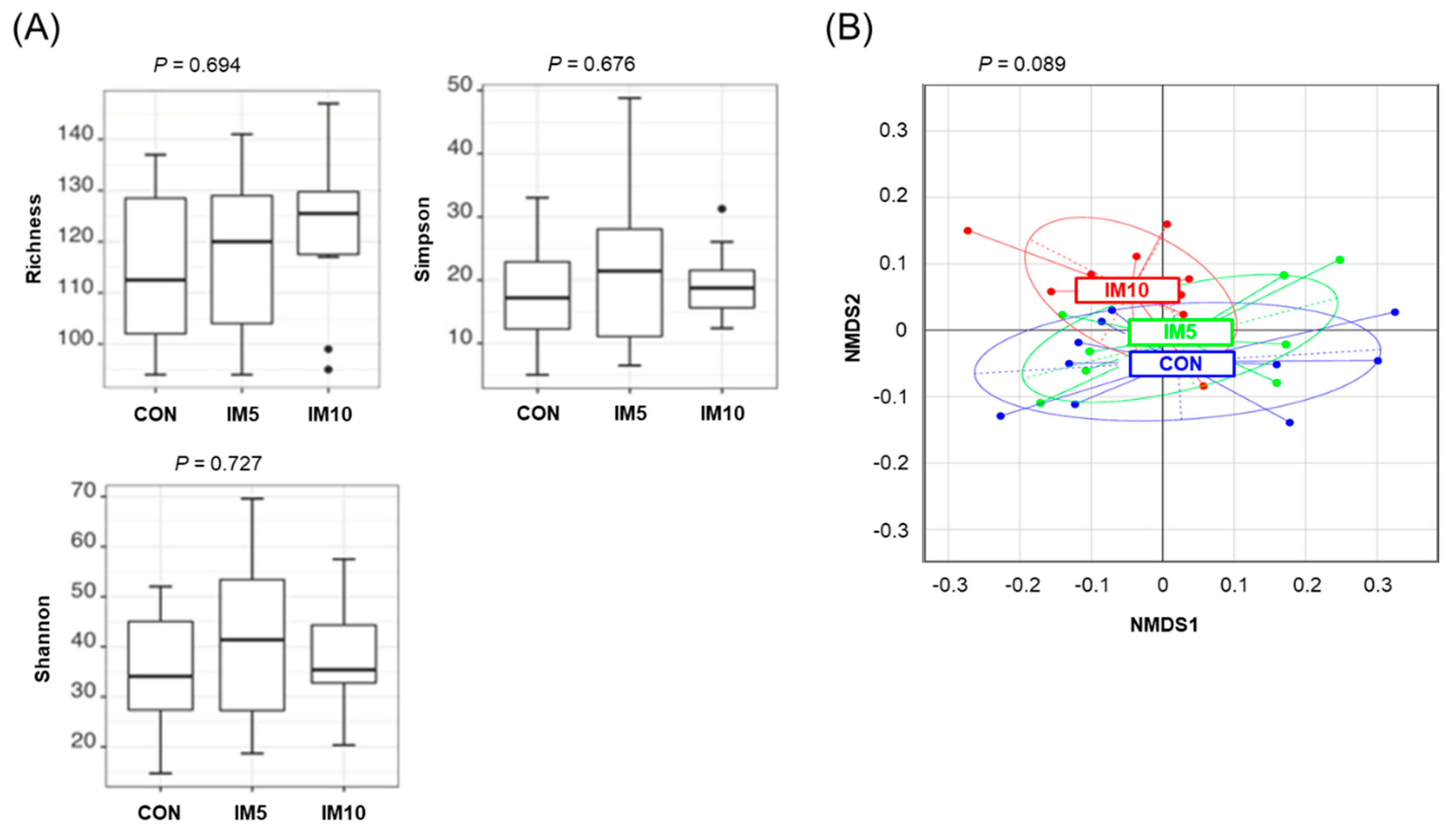

3.1. Microbiota Diversity in the Cecum of the Pigs

3.2. Microbiota Composition in the Cecum of the Pigs

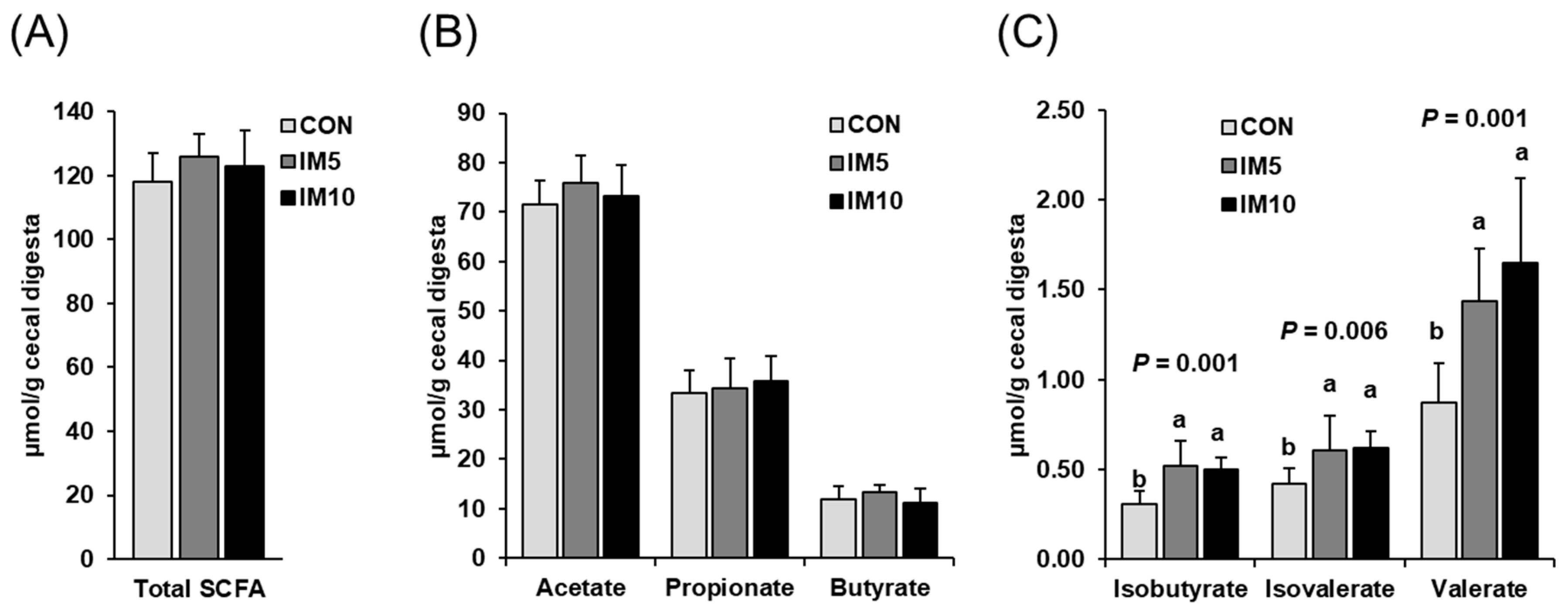

3.3. Concentrations of Microbial Fermentation Products in the Cecum of the Pigs

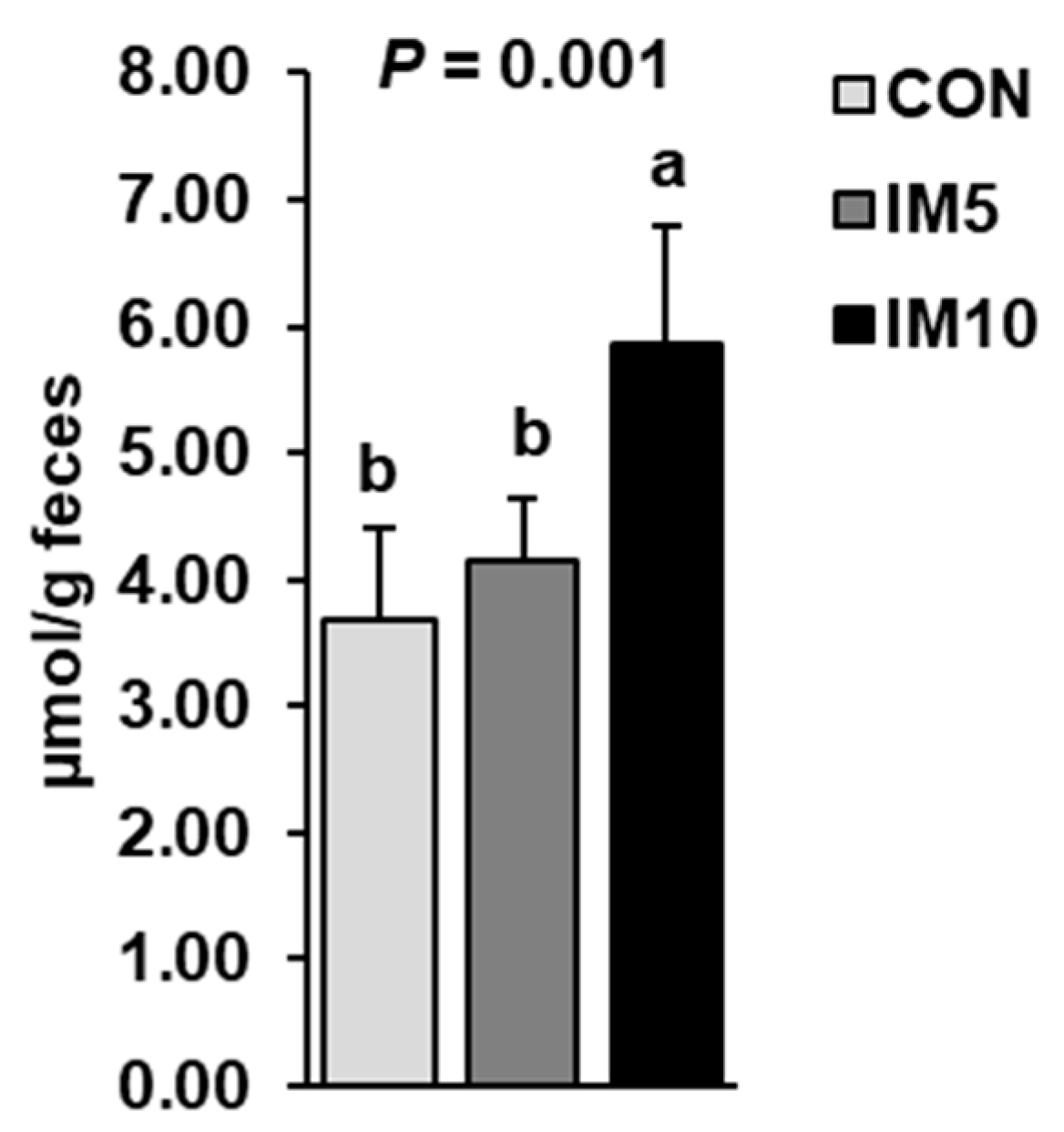

3.4. Concentrations of Bile Acids in the Feces of the Pigs

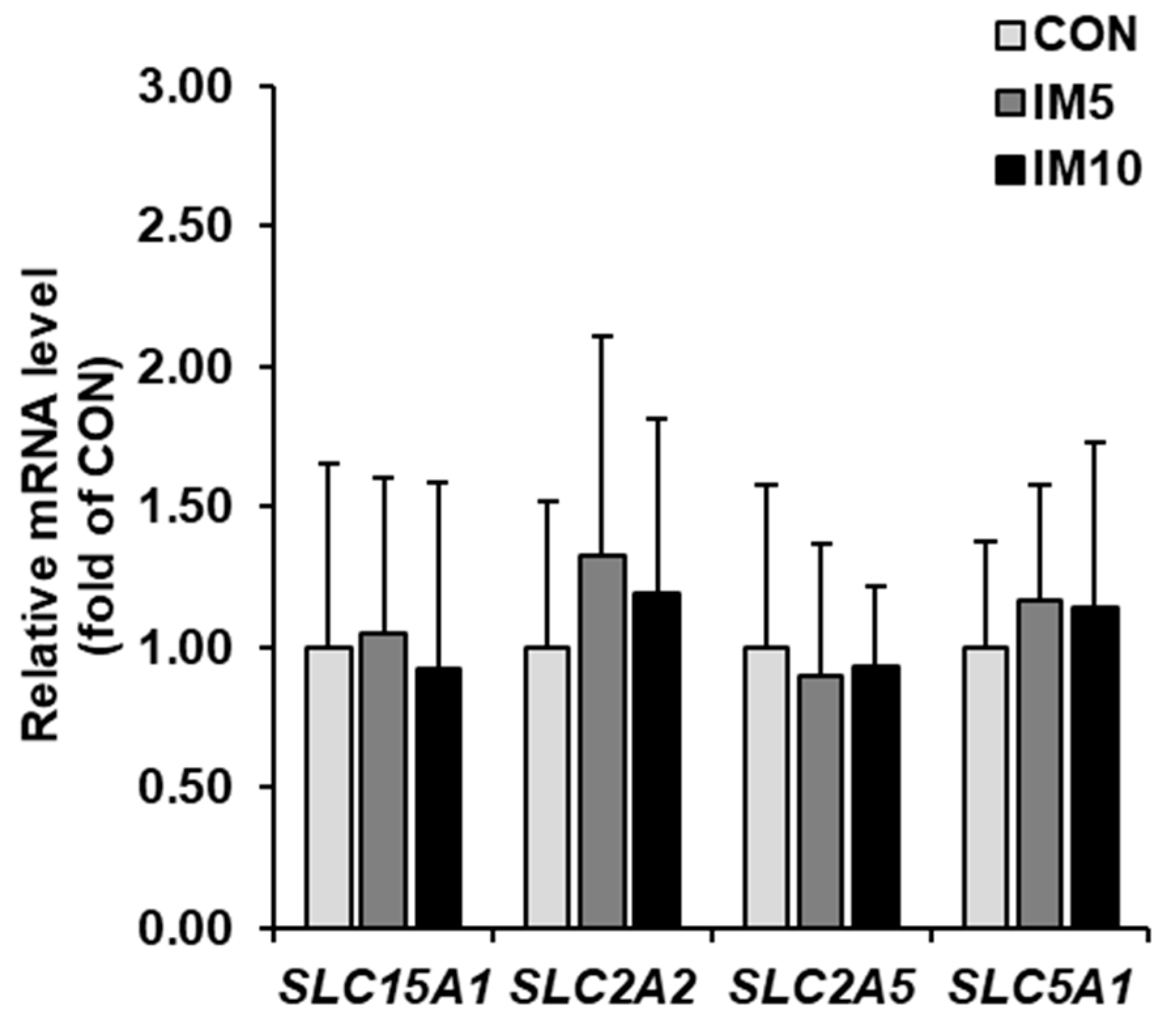

3.5. Expression of Carbohydrate and Peptide Transporters in Small Intestinal Mucosa of the Pigs

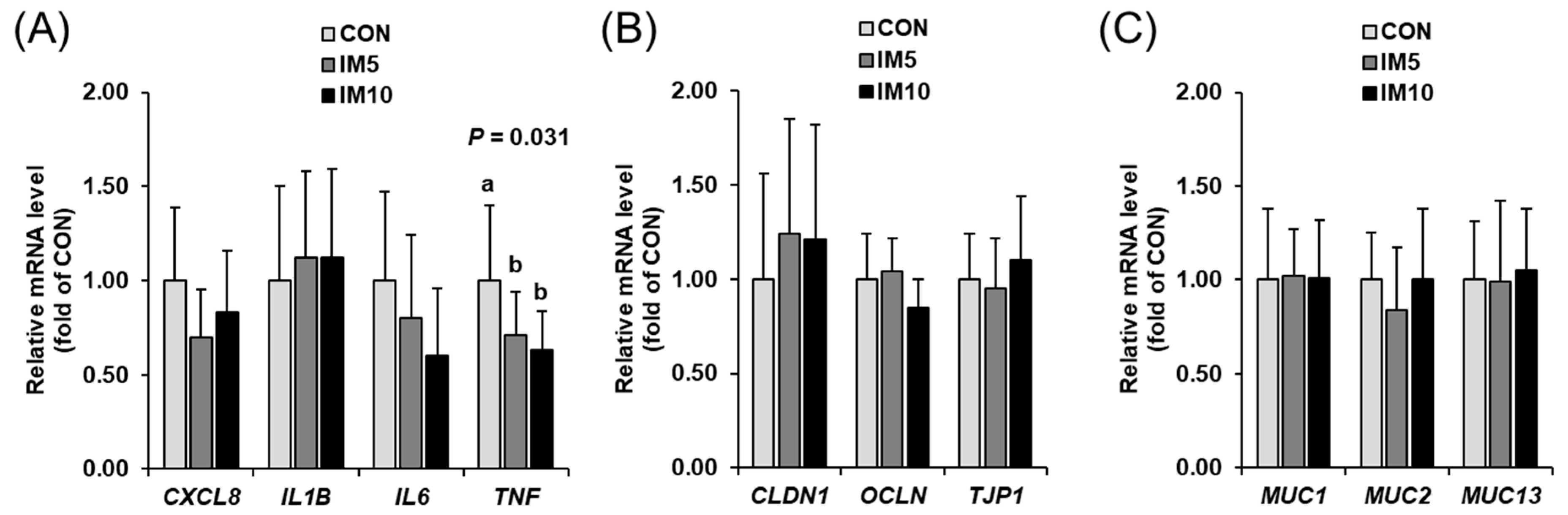

3.6. Expression of Genes Involved in Inflammation and Epithelial Barrier Function in Small Intestinal Mucosa of the Pigs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Huis, A.; Oonincx, D.G. The environmental sustainability of insects as food and feed. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchward-Venne, T.A.; Pinckaers, P.J.M.; van Loon, J.J.A.; van Loon, L.J.C. Consideration of insects as a source of dietary protein for human consumption. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasato, I.; De Marco, M.; Rotolo, L.; Renna, M.; Lussiana, C.; Dabbou, S.; Capucchio, M.T.; Biasibetti, E.; Costa, P.; Gai, F.; et al. Effects of dietary Tenebrio molitor meal inclusion in free-range chickens. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 100, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasco, L.; Biasato, I.; Dabbou, S.; Schiavone, A.; Gai, F. Animals Fed Insect-Based Diets: State-of-the-Art on Digestibility, Performance and Product Quality. Animals (Basel) 2019, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.; Gessner, D.K.; Braune, M.S.; Friedhoff, T.; Most, E.; Höring, M.; Liebisch, G.; Zorn, H.; Eder, K.; Ringseis, R. Comprehensive evaluation of the metabolic effects of insect meal from Tenebrio molitor L. in growing pigs by transcriptomics, metabolomics and lipidomics. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovera, F.; Loponte, R.; Marono, S.; Piccolo, G.; Parisi, G.; Iaconisi, V.; Gasco, L.; Nizza, A. Use of larvae meal as protein source in broiler diet: Effect on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, and carcass and meat traits. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.; Gessner, D.K.; Wen, G.; Most, E.; Liebisch, G.; Zorn, H.; Ringseis, R.; Eder, K. The Antisteatotic and Hypolipidemic Effect of Insect Meal in Obese Zucker Rats is Accompanied by Profound Changes in Hepatic Phospholipid and 1-Carbon Metabolism. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1801305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, M.M.; Edwards, C.H.; Mackie, A.R.; Gidley, M.J.; Butterworth, P.J.; Ellis, P.R. Re-evaluation of the mechanisms of dietary fibre and implications for macronutrient bioaccessibility, digestion and postprandial metabolism. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 816–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasato, I.; Ferrocino, I.; Biasibetti, E.; Grego, E.; Dabbou, S.; Sereno, A.; Gai, F.; Gasco, L.; Schiavone, A.; Cocolin, L.; et al. Modulation of intestinal microbiota, morphology and mucin composition by dietary insect meal inclusion in free-range chickens. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R.; Andersen, A.D.; Mølbak, L.; Stagsted, J.; Boye, M. Changes in the gut microbiota of cloned and non-cloned control pigs during development of obesity: Gut microbiota during development of obesity in cloned pigs. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.G.; Lee, J.Y.; Jin, G.D.; Park, J.; Choi, Y.H.; Chae, B.J.; Kim, E.B.; Choi, Y.J. Evaluating the association between body weight and the intestinal microbiota of weaned piglets via 16S rRNA sequencing. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 5903–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GfE (German Society for Nutrition Physiology). Recommendations for the Supply of Energy and Nutrients to Pigs; DLG: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- VDLUFA (Verband Deutscher Landwirtschaftlicher Untersuchungs- und Forschungsanstalten). Die chemische Untersuchung von Futtermitteln. In VDLUFA-Methodenbuch. Band III, Ergänzungslieferungen von 1983, 1988, 1992, 1997, 2004, 2006, 2007; VDLUFA: Darmstadt, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- GfE (German Society for Nutrition Physiology). Schätzgleichungen für Gras- und Maisprodukte sowie für Schweinemischfutter. Proc. Soc. Nutr. Phys. 2008, 17, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ringseis, R.; Rosenbaum, S.; Gessner, D.K.; Herges, L.; Kubens, J.F.; Mooren, F.C.; Krüger, K.; Eder, K. Supplementing obese Zucker rats with niacin induces the transition of glycolytic to oxidative skeletal muscle fibers. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozen, S.; Skaletsky, H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols; Krawetz, S., Misener, S., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 365–386. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, RESEARCH0034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagkouvardos, I.; Kläring, K.; Heinzmann, S.S.; Platz, S.; Scholz, B.; Engel, K.H.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Haller, D.; Rohn, S.; Skurk, T.; et al. Gut metabolites and bacterial community networks during a pilot intervention study with flaxseeds in healthy adult men. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1614–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dray, S.; Dufour, A.B. The ade4 Package: Implementing the Duality Diagram for Ecologists. J. Stat. Soft. 2007, 22, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Bittinger, K.; Charlson, E.S.; Hoffmann, C.; Lewis, J.; Wu, G.D.; Collman, R.G.; Bushman, F.D.; Li, H. Associating microbiome composition with environmental covariates using generalized UniFrac distances. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2106–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schliep, K.P. Phangorn: Phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 592–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrell, F.E., Jr. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Hmisc/index.html (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Lemon, J. Plotrix: A package in the red light district of R. R-News 2006, 6, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, B.G.; Carl, P. Econometric Tools for Performance and Risk Analysis [R package Performance Analytics version 2.0.4]: Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). 2020. Available online: https://cloud.r-project.org/web/packages/PerformanceAnalytics/index.html (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Wickham, H. Reshaping Data with the reshape Package. J. Stat. Soft. 2007, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2. Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste, A. Miscellaneous Functions for “Grid” Graphics [R package gridExtra version 2.3]: Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). 2017. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gridExtra/index.html (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Murrell, P. R graphics. In Computer Science and Data Analysis Series; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Slowikowski, K. Automatically Position Non-Overlapping Text Labels with’Ggplot2’ [R Package Ggrepel version 0.8.2]: Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggrepel/index.html (accessed on 3 November 2019).

- Wickham, H.; Pedersen, T.L. Arrange ‘Grobs’ in Tables [R package gtable version 0.3.0]: Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). 2019. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gtable/index.html (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M. Sparse and Dense Matrix Classes and Methods [R package Matrix version 1.2-18]: Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). 2019. Available online: https://cloud.r-project.org/web/packages/Matrix/index.html (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Minchin, P.R. Simulation of multidimensional community patterns: Towards a comprehensive model. Vegetatio 1987, 71, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Fiesel, A.; Gessner, D.K.; Most, E.; Eder, K. Effects of dietary polyphenol-rich plant products from grape or hop on pro-inflammatory gene expression in the intestine, nutrient digestibility and faecal microbiota of weaned pigs. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, Á.M.; Sweeney, T.; Hayes, M.; O’Doherty, J.V. Prawn Shell Chitosan Has Anti-Obesogenic Properties, Influencing Both Nutrient Digestibility and Microbial Populations in a Pig Model. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, E.; Kashimura, A.; Kikuchi, A.; Masuda, H.; Miyahara, R.; Hiruma, Y.; Wakita, S.; Ohno, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Sugahara, Y.; et al. Chitin digestibility is dependent on feeding behaviors, which determine acidic chitinase mRNA levels in mammalian and poultry stomachs. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, L.; Sauer, W.C.; Kozikowski, V.; Ryan, K.; Jorgensen, H.; Jelen, P. Nutritive value of protein extracted from honey bees. J. Food Sci. 1985, 50, 1327–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapola, N.S.; Lyyra, M.L.; Kolehmainen, R.M.; Sarkkinen, E.S.; Schauss, A.G. Safety aspects and 9cholesterol-lowering efficacy of chitosan tablets. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2008, 27, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, V.; Cheema, S.K.; Agellon, L.B.; Ooraikul, B.; Basu, T.K. Dietary rhubarb (Rheum rhaponticum) stalk fibre stimulates cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase gene expression and bile acid excretion in cholesterol-fed C57BL/6J mice. Br. J. Nutr. 1999, 81, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabler, N.; Spurlock, M. Integrating the immune system with the regulation of growth and efficiency. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, E64–E74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyuktimkin, B.; Zafar, H.; Saier, M.H., Jr. Comparative genomics of the transportome of Ten Treponema species. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 132, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, P.; Hold, G.L.; Flint, H.J. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachier, F.; Mariotti, F.; Huneau, J.F.; Tomé, D. Effects of amino acid-derived luminal metabolites on the colonic epithelium and physiopathological consequences. Amino Acids 2007, 33, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.A.; Macfarlane, G.T. Dissimilatory amino acid metabolism in human colonic bacteria. Anaerobe 1997, 3, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, A.M.; Sweeney, T.; Bahar, B.; Flynn, B.; O’Doherty, J.V. The effects of supplementing varying molecular weights of chitooligosaccharide on performance, selected microbial populations and nutrient digestibility in the weaned pig. Animal 2013, 7, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaumont, M.; Andriamihaja, M.; Lan, A.; Khodorova, N.; Audebert, M.; Blouin, J.M.; Grauso, M.; Lancha, L.; Benetti, P.H.; Benamouzig, R.; et al. Detrimental effects for colonocytes of an increased exposure to luminal hydrogen sulfide: The adaptive response. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 93, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, T.; Alaniz, R.C.; Wood, T.K.; Jayaraman, A. The bacterial signal indole increases epithelial-cell tight-junction resistance and attenuates indicators of inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | CON | IM5 | IM10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components, g/kg | ||||

| Wheat | 380 | 380 | 380 | |

| Barley | 250 | 250 | 250 | |

| Soybean meal (44% crude protein/kg FM) | 147.8 | 73.9 | - | |

| Tenebrio molitor larvae meal (70% crude protein/kg FM) | - | 50 | 100 | |

| Broad bean | 110 | 110 | 110 | |

| Soybean oil | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | |

| Rapseed oil | 4.40 | 2.10 | - | |

| Safflower oil | 3.00 | 1.60 | - | |

| Corn starch | 3.90 | 3.00 | 1.50 | |

| Cellulose | - | 28.0 | 56.5 | |

| Mineral and vitamin premix1 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 | |

| Monocalcium phosphate | 6.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 | |

| Calcium carbonate | 0.70 | 1.10 | 1.60 | |

| L-lysine | 0.70 | 1.00 | 1.40 | |

| DL-methionine | - | 0.10 | 0.10 | |

| L-threonine | 0.20 | 0.10 | - | |

| L-tryptophan | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.20 | |

| L-glutamic acid | 3.20 | 2.60 | 1.90 | |

| L-cysteine | - | 0.40 | 0.80 | |

| Titanium dioxide | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | |

| Analyzed crude nutrient and energy content | ||||

| Dry matter, % of FM | 87.6 | 87.9 | 88.5 | |

| Crude protein, % of DM | 22.2 | 22.7 | 22.8 | |

| Ether extract, % of DM | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.3 | |

| Crude ash, % of DM | 5.8 | 5.4 | 5.0 | |

| Crude fiber, % of DM | 6.3 | 8.0 | 9.7 | |

| Starch, % of DM | 45.6 | 46.3 | 46.2 | |

| Gross energy, MJ/kg DM | 19.5 | 19.3 | 19.6 | |

| Calculated energy content | ||||

| Metabolizable energy, MJ/kg DM | 14.6 | 14.1 | 13.5 | |

| Analyzed amino acid content, g/kg DM | ||||

| Alanine | 7.8 | 9.1 | 9.5 | |

| Arginine | 12.5 | 12.0 | 11.2 | |

| Aspartic acid | 14.6 | 14.4 | 13.0 | |

| Cysteine | 5.5 | 5.8 | 5.8 | |

| Glutamic acid | 46.5 | 46.1 | 41.0 | |

| Glycine | 8.2 | 8.6 | 8.7 | |

| Histidine | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.0 | |

| Isoleucine | 8.6 | 8.9 | 8.7 | |

| Leucine | 14.1 | 14.6 | 14.2 | |

| Lysine | 13.7 | 15.8 | 15.3 | |

| Methionine | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | |

| Phenylalanine | 9.2 | 9.2 | 8.4 | |

| Proline | 12.2 | 13.4 | 13.8 | |

| Serine | 7.9 | 8.1 | 7.6 | |

| Taurine | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.6 | |

| Threonine | 7.9 | 9.2 | 8.7 | |

| Tryptophan | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.0 | |

| Tyrosine | 6.4 | 7.4 | 7.6 | |

| Valine | 9.9 | 10.7 | 11.2 | |

| Analyzed mineral content, g/kg DM | ||||

| Calcium | 9.9 | 9.6 | 9.5 | |

| Phosphorus | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | |

| Item | Insect Meal |

|---|---|

| Crude nutrients | |

| Crude protein, % of DM | 74.0 |

| Ether extract, % of DM | 10.3 |

| Crude fiber, % of DM | 9.5 |

| Crude ash, % of DM | 5.5 |

| Chitin, % of DM | 9.7 |

| Gross energy, MJ/kg DM | 23.3 |

| Amino acids (g/kg DM) | |

| Alanine | 49.9 |

| Arginine | 34.4 |

| Aspartic acid | 61.2 |

| Cysteine | 5.7 |

| Glutamic acid | 86.8 |

| Glycine | 35.0 |

| Histidine | 18.1 |

| Isoleucine | 28.6 |

| Leucine | 51.2 |

| Lysine | 34.9 |

| Methionine | 8.1 |

| Phenylalanine | 24.2 |

| Proline | 57.5 |

| Serine | 31.2 |

| Threonine | 28.1 |

| Tryptophan | 7.9 |

| Tyrosine | 47.6 |

| Valine | 39.8 |

| Fatty acids1 (g/100 g total FAME) | |

| 12:0 | 0.3 |

| 14:0 | 2.4 |

| 16:0 | 15.5 |

| 16:1n-9 | 0.7 |

| 18:0 | 4.5 |

| 18:1n-9 | 35.0 |

| 18:2n-6 | 39.2 |

| 18:3n-3 | 1.5 |

| 20:0 | 0.1 |

| Classification Levels of Bacteria | CON | IM5 | IM10 | Pooled SD | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Order | Family | Genus | |||||

| Actinobacteria | Bifidobacteriales | Bifidobacteriaceae | Bifidobacterium | 0.00 b | 0.02 ab | 0.09 a | 0.08 | 0.002 |

| Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidales | Bacteroidaceae | Bacteroides | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.458 |

| Porphyromonadaceae | Barnesiella | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.407 | ||

| Parabacteroides | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.108 | |||

| unknown | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.450 | |||

| Prevotellaceae | Alloprevotella | 6.42 | 7.53 | 8.08 | 2.26 | 0.208 | ||

| Prevotella | 47.0 | 41.8 | 39.0 | 9.64 | 0.123 | |||

| unknown | 3.15 | 3.89 | 2.47 | 2.26 | 0.662 | |||

| Rikenellaceae | Alistipes | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.080 | ||

| unknown | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.78 | 0.837 | |||

| unknown | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.45 | 0.95 | 0.772 | |||

| Firmicutes | Bacillales | Bacillaceae 1 | Bacillus | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.992 |

| Staphylococcaceae | Staphylococcus | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.372 | ||

| Lactobacillales | Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus | 2.16 | 2.68 | 4.22 | 2.55 | 0.164 | |

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.063 | ||

| Clostridiales | Clostridiaceae 1 | Clostridium sensu stricto | 3.41 | 4.03 | 4.04 | 2.88 | 0.416 | |

| Lachnospiraceae | Blautia | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.87 | 0.47 | 0.107 | ||

| Clostridium XlVa | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.661 | |||

| Coprococcus | 0.10 a | 0.07 ab | 0.02 b | 0.06 | 0.011 | |||

| Fusicatenibacter | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.958 | |||

| Lachnospiracea incertae sedis | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.357 | |||

| Roseburia | 4.17 | 4.98 | 3.68 | 1.73 | 0.276 | |||

| unknown | 4.68 | 5.65 | 2.83 | 3.47 | 0.432 | |||

| Peptostreptococcaceae | Clostridium XI | 0.57 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 0.327 | ||

| Ruminococcaceae | Clostridium IV | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.522 | ||

| Faecalibacterium | 2.92 | 2.24 | 1.43 | 1.76 | 0.618 | |||

| Gemmiger | 1.20 | 1.28 | 1.18 | 0.78 | 0.956 | |||

| Oscillibacter | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.41 | 0.953 | |||

| Ruminococcus | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.405 | |||

| unknown | 2.68 | 3.73 | 2.42 | 2.42 | 0.547 | |||

| unknown | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 0.910 | |||

| Selenomonadales | Acidaminococcaceae | Phascolarctobacterium | 1.64 | 1.87 | 2.11 | 0.86 | 0.257 | |

| Veillonellaceae | Anaerovibrio | 1.65 | 2.16 | 2.24 | 1.67 | 0.256 | ||

| Dialister | 0.91 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.17 | 0.937 | |||

| Megasphaera | 0.31 | 0.42 | 1.31 | 1.29 | 0.135 | |||

| Mitsuokella | 0.73 | 1.05 | 2.38 | 1.71 | 0.239 | |||

| unknown | 2.83 | 4.15 | 5.57 | 2.79 | 0.150 | |||

| unknown | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.887 | |||

| Proteobacteria | unknown Betaproteobacteria | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.411 | ||

| unknown Deltaproteobacteria | 0.63 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.371 | |||

| Aeromonadales | Succinivibrionaceae | Succinivibrio | 1.16 | 0.77 | 1.44 | 1.01 | 0.657 | |

| Enterobacteriales | Enterobacteriaceae | Escherichia/Shigella | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.49 | 0.64 | 0.317 | |

| unknown Gammaproteobacteria | 2.16 | 1.60 | 5.27 | 3.24 | 0.158 | |||

| Spirochaetes | Spirochaetales | Spirochaetaceae | Treponema | 2.38 a | 1.06 ab | 0.10 b | 2.65 | 0.030 |

| Unknown | 0.41 | 0.66 | 0.95 | 0.102 | ||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meyer, S.; Gessner, D.K.; Maheshwari, G.; Röhrig, J.; Friedhoff, T.; Most, E.; Zorn, H.; Ringseis, R.; Eder, K. Tenebrio molitor Larvae Meal Affects the Cecal Microbiota of Growing Pigs. Animals 2020, 10, 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10071151

Meyer S, Gessner DK, Maheshwari G, Röhrig J, Friedhoff T, Most E, Zorn H, Ringseis R, Eder K. Tenebrio molitor Larvae Meal Affects the Cecal Microbiota of Growing Pigs. Animals. 2020; 10(7):1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10071151

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeyer, Sandra, Denise K. Gessner, Garima Maheshwari, Julia Röhrig, Theresa Friedhoff, Erika Most, Holger Zorn, Robert Ringseis, and Klaus Eder. 2020. "Tenebrio molitor Larvae Meal Affects the Cecal Microbiota of Growing Pigs" Animals 10, no. 7: 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10071151

APA StyleMeyer, S., Gessner, D. K., Maheshwari, G., Röhrig, J., Friedhoff, T., Most, E., Zorn, H., Ringseis, R., & Eder, K. (2020). Tenebrio molitor Larvae Meal Affects the Cecal Microbiota of Growing Pigs. Animals, 10(7), 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10071151