Autochthonous Probiotics in Meat Products: Selection, Identification, and Their Use as Starter Culture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characterization of Autochthonous Probiotics Found in Meat Products

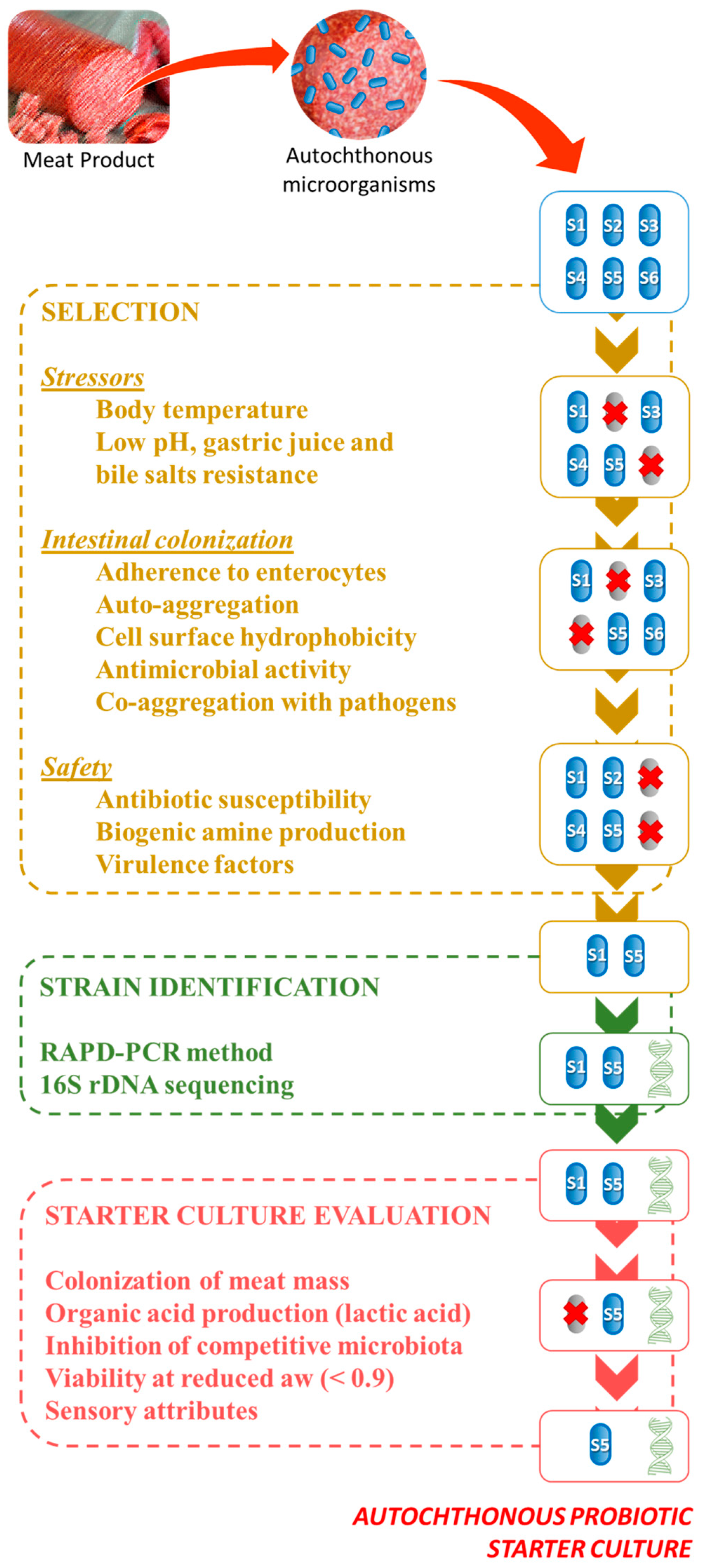

2.1. Selection Criteria for Probiotic Strains

| Source of Probiotic Microorganisms | Probiotic Selection Assays | Isolated Microorganisms | Potential Probiotics | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciauscolo salami (traditional Italian fermented sausage) | Resistance to low pH and bile salts, cell adhesion, and antibiotic resistance | 42 LAB 1 isolates comprising: Carnobacterium spp., Enterococcus faecalis, Lactobacillus brevis, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus johnsonii, Lactococcus lactis, Lactobacillus paracasei, Lactobacillus paraplantarum, Lactobacillus sakei, Lactococcus spp, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Pediococcus pentosaceus, and Weissella hellenica strains | P. pentosaceus 62781-3, 46035-1, and 46035-4, and L. mesenteroides 14324-8 | [26] |

| Traditional Portuguese fermented meat products | Resistance to low pH, bile salts, and body temperature; antimicrobial activity; and biogenic amine production | Enterococcus faecium 85, 101, 119, and 120 | E. faecium 120 | [29] |

| Harbin dry sausages (traditional Chinese fermented sausage) | Resistance to gastric transit and bile salts, auto-aggregation, cell adhesion, and hydrophobicity | P. pentosaceus R1, Lactobacillus brevis R4, Lactobacillus curvatus R5 and Lactobacillus fermentum R6 | L. brevis R4 | [27] |

| Meat products | Resistance to low pH, bile salts, and body temperature; biofilm formation; virulence factors; antibiotic resistance; and biogenic amine production | L. lactis subsp. cremoris CTCa 204, L. lactis subsp. hordiniae CTC 483, L. lactis subsp. cremoris CTC 484, Lactobacillus plantarum CTC 368, and L. plantarum CTC 469 | L. lactis CTC 204 and L. plantarum CTC 368 strains | [30] |

| Cured beef | Resistance to low pH and bile salts; antimicrobial activity; auto- and co-aggregation; cell adhesion and hydrophobicity; hemolytic activity; and antibiotic resistance | L. plantarum (CB9 and CB10) and Weissella cibaria CB12 | L. plantarum CB9 and CB10 strains | [28] |

| Sokobanja sausage (traditional Serbian sausage) | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion; antimicrobial activity; biogenic amine production; and antibiotic resistance | E. faecium sk6-1 and -17; sk7-5, 7 and 8; sk8-1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 12, 13, 17 and 20; sk9-3, 11 and 15; sk10-1, 7, 10 and 12 | E. faecium sk7-5, sk7-8 and sk9-15 | [31] |

| Meat sausage | Resistance to low pH and bile salts; antimicrobial activity; and antibiotic resistance | Pediococcus acidilactici CE51 | Suitable probiotic characteristics | [32] |

| Fermented pork sausages | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion, cell hydrophobicity, antimicrobial activity, and antibiotic resistance | 169 Lactobacillus spp. strains (L. curvatus, Lactobacillus reuteri, L. plantarum, Lactobacillus parapentarum, L. pentosus, Lactobacillus keferi, L. fermentum, Lactobacillus animalis, Lactobacillus mucosae, Lactobacillus aviaries ssp. aviaries, L. salivarius ssp. salicinus, L. salivarius ssp. salivarius, Lactobacillus hilgardii, and Lactobacillus panis) | L. fermentum 3007 and 3010 strains | [34] |

| Pork sausages | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion, cell hydrophobicity, auto- and co-aggregation, hemolytic activity, biogenic amine production, and antibiotic resistance | 32 Lactobacillus spp. strains | L. plantarum UFLA SAU 14, 20, 34, 52, 91, 172, 185, 187, 238, and 258 | [35] |

| Pastırma (Turkish cured beef product) | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion, cell hydrophobicity, auto- and co-aggregation, and cell adhesion | P. pentosaceus K7, K41, K44, K51, and K81 and P. acidilactici K99 | P. pentosaceus K41 and K44 and P. acidilactici K99 | [36] |

| Sucuk (Turkish fermented sausage) | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion, antimicrobial activity, auto- and co-aggregation, and antibiotic resistance | P. pentosaceus Z9P, Z12P, and Z13P, P. acidilactici Z10P, and P. dextrinicus Z11P | P. pentosaceus Z12P and Z13P | [37] |

| Dried Ossban (Tunisian fermented meat product) | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion, auto-aggregation, cell adhesion, virulence factors, biogenic amine production, bacteriocin production, antimicrobial activity, and antibiotic resistance | E. faecium strains MZF1, MZF2, MZF3, MZF4, and MZF5 | All strains | [38] |

| Scandinavian-type fermented sausages | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion, cell adhesion, and antimicrobial activity | Lactobacillus alimentarius MF1297, Lactobacillus farciminis DC11 and MF1288, Lactobacillus pentosus MF1300, L. plantarum DC13, MF1291, MF1298, Lactobacillus rhamnosus DC8, L. sakei MF1295, MF1296, Lactobacillus salivarius DC2, DC4, DC5, and P. pentosaceus DC12 | L. pentosus MF1300 and L. plantarum MF1291 and MF1298 strains | [39] |

| Spanish dry-cured sausages | Resistance to simulated intestinal digestion, biofilm formation; virulence factors, biogenic amine production, and antibiotic resistance | 46 LAB strains (E. faecium, Lactobacillus coryniformis, L. paracasei, L. plantarum, and L. sakei) | L. paracasei Al-128 and L. sakei Al-143 | [40] |

| Slavonski kulen sausage (traditional Croatian sausage) | Resistance to simulated intestinal digestion, antimicrobial activity, enterotoxin production, and antibiotic resistance | L. plantarum 1 K, L. delbrueckii 2 K, L. mesenteroides 6K1, L. acidophilus 7K2, S. xylosus 4K1, S. warneri 3K1, S. lentus 6K2, and S. auricularis 7K1 | All LAB and S. xylosus 4K1, S. warneri 3K1 strains | [41] |

| Slovak traditional sausages | Resistance to simulated intestinal digestion, antimicrobial activity, bacteriocin production, cell adhesion, biogenic amine production, and antibiotic resistance | S. xylosus and S. carnosus strains | S. xylosus SO3/1M/1/2 | [42] |

| Indian fermented meat | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion, cell hydrophobicity, auto-aggregation, antimicrobial activity, hemolytic activity, and antibiotic resistance | Staphylococcus sp. DBOCP6 | Suitable probiotic characteristics | [33] |

| Fermented meat products | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion, hemolytic activity, cell adhesion, cholesterol-lowering property, and antibiotic resistance | 12 γ-aminobutyric acid-producing strains | P. pentosaceus HN8 and L. namurensis NH2 | [43] |

| Vienna sausages | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion, cell hydrophobicity, cell adhesion, auto- and co-aggregation, and antibiotic resistance | E. faecium UAM1, UAM2, UAM3, UAM4, UAM5, and UAM6 | E. faecium UAM1 | [44] |

| Iberian dry fermented sausages | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion | 15 LAB and bifidobacteria strains (Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacteria spp., Lactococcus spp., and Enterococcus spp.) | P. acidilactici KKA and UGA146-3 and E. faecium CICC 6078, CK1013, and IDCC 2102 | [45] |

| Traditional dry fermented sausages | Resistance to simulated gastrointestinal digestion | 20 Lactobacillus spp. strains | L. brevis AY318799, AY318801, and AY318804, L. curvatus AY318826, L. fermentum AY318825, L. paracasei ssp. paracasei AY318806, AY318809, and AY318824, and L. plantarum AY318822 | [46] |

2.2. Identification Probiotic Strains

3. Application of Autochthonous Probiotics in Meat Products

| Probiotic Microorganisms | Meat Product | Inoculum Count and Processing Conditions | Influence on Meat Product Quality Indicators | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. plantarum 178 | Sweet Calabrian salami | 10 log CFU/g; stewing stage for 4 h at 22 °C and RH of 99%; drying stage for 7 h at 22 °C and RH of 65%; intermediate drying/ripening stage for 4 days from 20 to 15 °C, and RH from 67% to 73%; first ripening stage for 5 days at 15 °C and RH of 71%; second ripening stage for 5 days at 13 °C and RH of 73%, and final ripening/maturation stage for 15 days at 12 °C and RH of 75% | Increased LAB count; reduced pH; inhibited enterobacteria growth | [53] |

| L. plantarum IIA-2C12 | Fermented lamb sausage | 9 log CFU 1/mL; drying for 1 day 25 °C, cold smoking for 3 days at 27 °C | Reduced pH, aw 2 and Escherichia coli count; increased LAB 3 count, acidity, lactic acid content, and sensory acceptance | [54] |

| L. plantarum IIA-2C12 and Lactobacillus acidophilus IIA-2B4 | Fermented beef sausage | 9 log CFU/g; conditioning for 24 h at 27–29 °C and RH 4 88–90%, cold smoking (three times) for 4 h (12 h in total) at 27–29 °C, and fermentation for 24 h at RT 5 | Reduced pH, lipid oxidation, hardness, Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli counts; increased acidity, color, LAB count and volatile compounds; not meaningful changes on fatty acid profile, aw and sensory attributes | [55] |

| L. plantarum L125 | Pork fermented sausage | 8 log CFU/g; fermentation for 4 days; ripening for 8 days | High counts of LAB and staphylococci; increased redness, raw odor and acidic taste; reduced pH and aw; final product was microbiologically safe | [56] |

| L. sakei 8416 and L. sakei 4413 | Beef and pork fermented sausage | 7 log CFU/g; fermented for 6 days from 20 to 15 °C, RH from 95 to 80% and air velocity from 0.7 to 0.5 m/s, smoked for 3 h; ripened for 21 days at 15 °C, RH 80% and air velocity at 0.05–0.1 m/s | Increased LAB count; absence of L. monocytogenes and presumptive E. coli O157; reduced pH and aw | [57] |

| Mix with 10 L. plantarum strains | Fermented pork sausage | 7 log CFU/g; 30 days at 10 °C | Increased LAB count; reduced S. typhi and L. monocytogenes counts, and pH | [35] |

| P. acidilactici SP979 | Spanish salchichón | 7.5 log CFU/g; 10 °C and 80% RH for 22 days at 12 °C and 70% RH for 26 days | Increased moisture and protein content; reduced pH, lipid content and oxidation, | [58] |

| P. pentosaceus HN8 and L. namurensis NH2 | Thai fermented pork sausage (Nham) | 6 log CFU/g for each strain; fermented for 4 days | Reduced biogenic amines and cholesterol contents | [60] |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ojha, K.S.; Kerry, J.P.; Duffy, G.; Beresford, T.; Tiwari, B.K. Technological advances for enhancing quality and safety of fermented meat products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 44, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; Geyzen, A.; Janssens, M.; De Vuyst, L.; Scholliers, P. Meat fermentation at the crossroads of innovation and tradition: A historical outlook. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 31, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anal, A.K. Quality ingredients and safety concerns for traditional fermented foods and beverages from Asia: A review. Fermentation 2019, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talon, R.; Leroy, S.; Lebert, I. Microbial ecosystems of traditional fermented meat products: The importance of indigenous starters. Meat Sci. 2007, 77, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, L.C.; Henchion, M.; De Brún, A.; Murrin, C.; Wall, P.G.; Monahan, F.J. Factors that predict consumer acceptance of enriched processed meats. Meat Sci. 2017, 133, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; Scholliers, P.; Amilien, V. Elements of innovation and tradition in meat fermentation: Conflicts and synergies. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 212, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, D.; Barba, F.J.; Kovačević, B.D.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Cruz, A.G.; Putnik, P. Functional foods: Product development, technological trends, efficacy testing, and safety. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, M.Z.; Abhari, K.; Barzegar, F.; Hosseini, H. Functional meat products: The new consumer’s demand. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 16, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bis-Souza, C.V.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Penna, A.L.B.; Barretto, A.C.S. New strategies for the development of innovative fermented meat products: A review regarding the incorporation of probiotics and dietary fibers. Food Rev. Int. 2019, 35, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syngai, G.G.; Gopi, R.; Bharali, R.; Dey, S.; Lakshmanan, G.M.A.; Ahmed, G. Probiotics—The versatile functional food ingredients. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food; FAO/WHO: London, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bis-Souza, C.V.; Pateiro, M.; Domínguez, R.; Penna, A.L.B.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barretto, A.C.D.S. Impact of fructooligosaccharides and probiotic strains on the quality parameters of low-fat Spanish Salchichón. Meat Sci. 2020, 159, 107936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bis-Souza, C.V.; Pateiro, M.; Domínguez, R.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Penna, A.L.B.; Barretto, A.C.D.S. Volatile profile of fermented sausages with commercial probiotic strains and fructooligosaccharides. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 5465–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Chatli, M.K.; Verma, A.K.; Mehta, N.; Malav, O.P.; Kumar, D.; Sharma, N. Quality, functionality, and shelf life of fermented meat and meat products: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2844–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration Microorganisms & Microbial-Derived Ingredients Used in Food (Partial List). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras/microorganisms-microbial-derived-ingredients-used-food-partial-list (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Domínguez, R. Role of autochthonous starter cultures in the reduction of biogenic amines in traditional meat products. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-L.; Liou, J.-M.; Lu, T.-M.; Lin, Y.-H.; Wang, C.-K.; Pan, T.-M. Effects of Vigiis 101-LAB on a healthy population’s gut microflora, peristalsis, immunity, and anti-oxidative capacity: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafi, A.; Namazi, G.; Soleimani, A.; Bahmani, F.; Aghadavod, E.; Asemi, Z. Metabolic and genetic response to probiotics supplementation in patients with diabetic nephropathy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 4763–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnason, I.; Sission, G.; Hayee, B.H. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a multi-strain probiotic in patients with asymptomatic ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, M.; Elias, M.; Fraqueza, M.J. The use of starter cultures in traditional meat products. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruxen, C.E.D.S.; Funck, G.D.; Haubert, L.; Dannenberg, G.D.S.; Marques, J.D.L.; Chaves, F.C.; da Silva, W.P.; Fiorentini, Â.M. Selection of native bacterial starter culture in the production of fermented meat sausages: Application potential, safety aspects, and emerging technologies. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelschlaeger, T.A. Mechanisms of probiotic actions—A review. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 300, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokryazdan, P.; Jahromi, M.F.; Liang, J.B.; Ho, Y.W. Probiotics: From isolation to application. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2017, 36, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.; Shukla, P. An overview of advanced technologies for selection of probiotics and their expediency: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3233–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, G.V.D.M.; Neto, D.P.D.C.; Junqueira, A.C.D.O.; Karp, S.G.; Letti, L.A.J.; Júnior, A.I.M.; Soccol, C.R. A Review of selection criteria for starter culture development in the food fermentation industry. Food Rev. Int. 2020, 36, 135–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, S.; Ciarrocchi, F.; Campana, R.; Ciandrini, E.; Blasi, G.; Baffone, W. Identification and functional traits of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Ciauscolo salami produced in Central Italy. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Kong, B.; Chen, Q.; Sun, F.; Zhang, H. In vitro comparison of probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Harbin dry sausages and selected probiotics. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 32, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, K.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Wei, X.; Fan, M. Screening for potential probiotic from spontaneously fermented non-dairy foods based on in vitro probiotic and safety properties. Ann. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.; Borges, S.; Teixeira, P. Selection of potential probiotic Enterococcus faecium isolated from Portuguese fermented food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 191, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, I.; Marasca, E.T.G.; De Sá, P.B.Z.R.; Moitinho, D.S.J.; Marquezini, M.G.; Alves, M.R.C.; Bromberg, R. Evaluation of probiotic potential of bacteriocinogenic lactic acid bacteria strains isolated from meat products. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2018, 10, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, T.D.Ž.; Ilić, P.D.; Grujović, M.Z.; Mladenović, K.G.; Kocić-Tanackov, S.D.; Čomić, L.R. Assessment of safety aspect and probiotic potential of autochthonous Enterococcus faecium strains isolated from spontaneous fermented sausage. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 1513–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, K.C.D.O.; Ferreira, C.D.S.; Bueno, E.B.T.; de Moraes, Y.A.; Toledo, A.C.C.G.; Nakagaki, W.R.; Pereira, V.C.; Winkelstroter, L.K. Development and viability of probiotic orange juice supplemented by Pediococcus acidilactici CE51. LWT 2020, 130, 109637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, D.B.Y.; Gogoi, O.; Adhikari, C.; Kakoti, B.B. Isolation and characterization of the new indigenous Staphylococcus sp. DBOCP06 as a probiotic bacterium from traditionally fermented fish and meat products of Assam state. Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2016, 3, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klayraung, S.; Viernstein, H.; Sirithunyalug, J.; Okonogi, S. Probiotic properties of lactobacilli isolated from Thai traditional food. Sci. Pharm. 2008, 76, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, F.S.; Duarte, W.F.; Santos, M.R.R.M.; Ramos, E.M.; Schwan, R.F. Screening of Lactobacillus isolated from pork sausages for potential probiotic use and evaluation of the microbiological safety of fermented products. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topçu, K.C.; Kaya, M.; Kaban, G. Probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria strains isolated from pastırma. LWT 2020, 134, 110216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksekdag, Z.N.; Aslim, B. Assessment of potential probiotic and starter properties of Pediococcus spp. isolated from Turkish-type fermented sausages (Sucuk). J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 20, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zommiti, M.; Cambronel, M.; Maillot, O.; Barreau, M.; Sebei, K.; Feuilloley, M.; Ferchichi, M.; Connil, N. Evaluation of probiotic properties and safety of Enterococcus faecium isolated from artisanal Tunisian meat “Dried Ossban”. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingberg, T.D.; Axelsson, L.; Naterstad, K.; Elsser, D.; Budde, B.B. Identification of potential probiotic starter cultures for Scandinavian-type fermented sausages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 105, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta, G.; Curiel, J.A.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Muñoz, R.; Rivas, D.L.B. Technological and safety properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Spanish dry-cured sausages. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić, I.; Markov, K.; Kovačević, D.; Trontel, A.; Slavica, A.; Dugum, J.; Čvek, D.; Svetec, I.K.; Posavec, S.; Frece, J. Identification and characterization of potential autochthonous starter cultures from a Croatian “brand” product “Slavonski kulen”. Meat Sci. 2011, 88, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonová, M.P.; Strompfová, V.; Marciňáková, M.; Lauková, A.; Vesterlund, S.; Moratalla, M.L.; Bover-Cid, S.; Vidal-Carou, C. Characterization of Staphylococcus xylosus and Staphylococcus carnosus isolated from slovak meat products. Meat Sci. 2006, 73, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanaburee, A.; Kantachote, D.; Charernjiratrakul, W.; Sukhoom, A. selection of γ-aminobutyric acid-producing lactic acid bacteria and their potential as probiotics for use as starter cultures in Thai fermented sausages (Nham). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Alcántara, A.M.; Wacher, C.; Llamas, M.G.; López, P.; Pérez-Chabela, M.L. Probiotic properties and stress response of thermotolerant lactic acid bacteria isolated from cooked meat products. LWT 2018, 91, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Martín, A.; Benito, M.J.; Perez-Nevado, F.; Córdoba, M.D.G. Screening of lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria for potential probiotic use in Iberian dry fermented sausages. Meat Sci. 2008, 80, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennacchia, C.; Ercolini, D.; Blaiotta, G.; Pepe, O.; Mauriello, G.; Villani, F. Selection of Lactobacillus strains from fermented sausages for their potential use as probiotics. Meat Sci. 2004, 67, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abid, Y.; Casillo, A.; Gharsallah, H.; Joulak, I.; Lanzetta, R.; Corsaro, M.M.; Attia, H.; Azabou, S. Production and structural characterization of exopolysaccharides from newly isolated probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, M.; Baldi, A. Selective identification and charcterization of potential probiotic strains: A review on comprehensive polyphasic approach. Appl. Clin. Res. Clin. Trials Regul. Aff. 2017, 4, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Falony, G.; Leroy, F. Probiotics in fermented sausages. Meat Sci. 2008, 80, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Työppönen, S.; Petäjä, E.; Mattila-Sandholm, T. Bioprotectives and probiotics for dry sausages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 83, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspri, M.; Papademas, P.; Tsaltas, D. Review on non-dairy probiotics and their use in non-dairy based products. Fermentation 2020, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, M.; Bunt, C.R.; Mason, S.L.; Hussain, M.A. Non-dairy probiotic food products: An emerging group of functional foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2626–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campaniello, D.; Speranza, B.; Bevilacqua, A.; Altieri, C.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M. Industrial validation of a promising functional strain of Lactobacillus plantarum to improve the quality of Italian sausages. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arief, I.I.; Wulandari, Z.; Aditia, E.L.; Baihaqi, M.; Noraimah; Hendrawan. Physicochemical and microbiological properties of fermented lamb sausages using probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum IIA-2C12 as starter culture. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2014, 20, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arief, I.I.; Afiyah, D.N.; Wulandari, Z.; Budiman, C. Physicochemical properties, fatty acid profiles, and sensory characteristics of fermented beef sausage by probiotics Lactobacillus plantarum IIA-2C12 or Lactobacillus acidophilus IIA-2B4. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, M2761–M2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavli, F.G.; Argyri, A.A.; Chorianopoulos, N.G.; Nychas, G.J.E.; Tassou, C.C. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum L125 strain with probiotic potential on physicochemical, microbiological and sensorial characteristics of dry-fermented sausages. Lwt 2020, 118, 108810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragalaki, T.; Bloukas, J.G.; Kotzekidou, P. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli O157: H7 in liquid broth medium and during processing of fermented sausage using autochthonous starter cultures. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Martín, A.; Benito, M.J.; Hernández, A.; Casquete, R.; Córdoba, D.g.M. Application of Lactobacillus fermentum HL57 and Pediococcus acidilactici SP979 as potential probiotics in the manufacture of traditional Iberian dry-fermented sausages. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainar, M.S.; Stavropoulou, D.A.; Leroy, F. Exploring the metabolic heterogeneity of coagulase-negative staphylococci to improve the quality and safety of fermented meats: A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 247, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantachote, D.; Ratanaburee, A.; Sukhoom, A.; Sumpradit, T.; Asavaroungpipop, N. Use of γ-aminobutyric acid producing lactic acid bacteria as starters to reduce biogenic amines and cholesterol in Thai fermented pork sausage (Nham) and their distribution during fermentation. LWT 2016, 70, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, S.K.; Uddin, M.M.; Rahman, R.; Islam, S.M.R.; Khan, M.S. A review on mechanisms and commercial aspects of food preservation and processing. Agric. Food Secur. 2017, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Munekata, P.E.S.; Pateiro, M.; Zhang, W.; Domínguez, R.; Xing, L.; Fierro, E.M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Autochthonous Probiotics in Meat Products: Selection, Identification, and Their Use as Starter Culture. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8111833

Munekata PES, Pateiro M, Zhang W, Domínguez R, Xing L, Fierro EM, Lorenzo JM. Autochthonous Probiotics in Meat Products: Selection, Identification, and Their Use as Starter Culture. Microorganisms. 2020; 8(11):1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8111833

Chicago/Turabian StyleMunekata, Paulo E. S., Mirian Pateiro, Wangang Zhang, Rubén Domínguez, Lujuan Xing, Elena Movilla Fierro, and José M. Lorenzo. 2020. "Autochthonous Probiotics in Meat Products: Selection, Identification, and Their Use as Starter Culture" Microorganisms 8, no. 11: 1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8111833

APA StyleMunekata, P. E. S., Pateiro, M., Zhang, W., Domínguez, R., Xing, L., Fierro, E. M., & Lorenzo, J. M. (2020). Autochthonous Probiotics in Meat Products: Selection, Identification, and Their Use as Starter Culture. Microorganisms, 8(11), 1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8111833