Microbial Community Succession During Bioremediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soils Using Rhodococcus sp. OS62-1 and Pseudomonas sp. P35

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

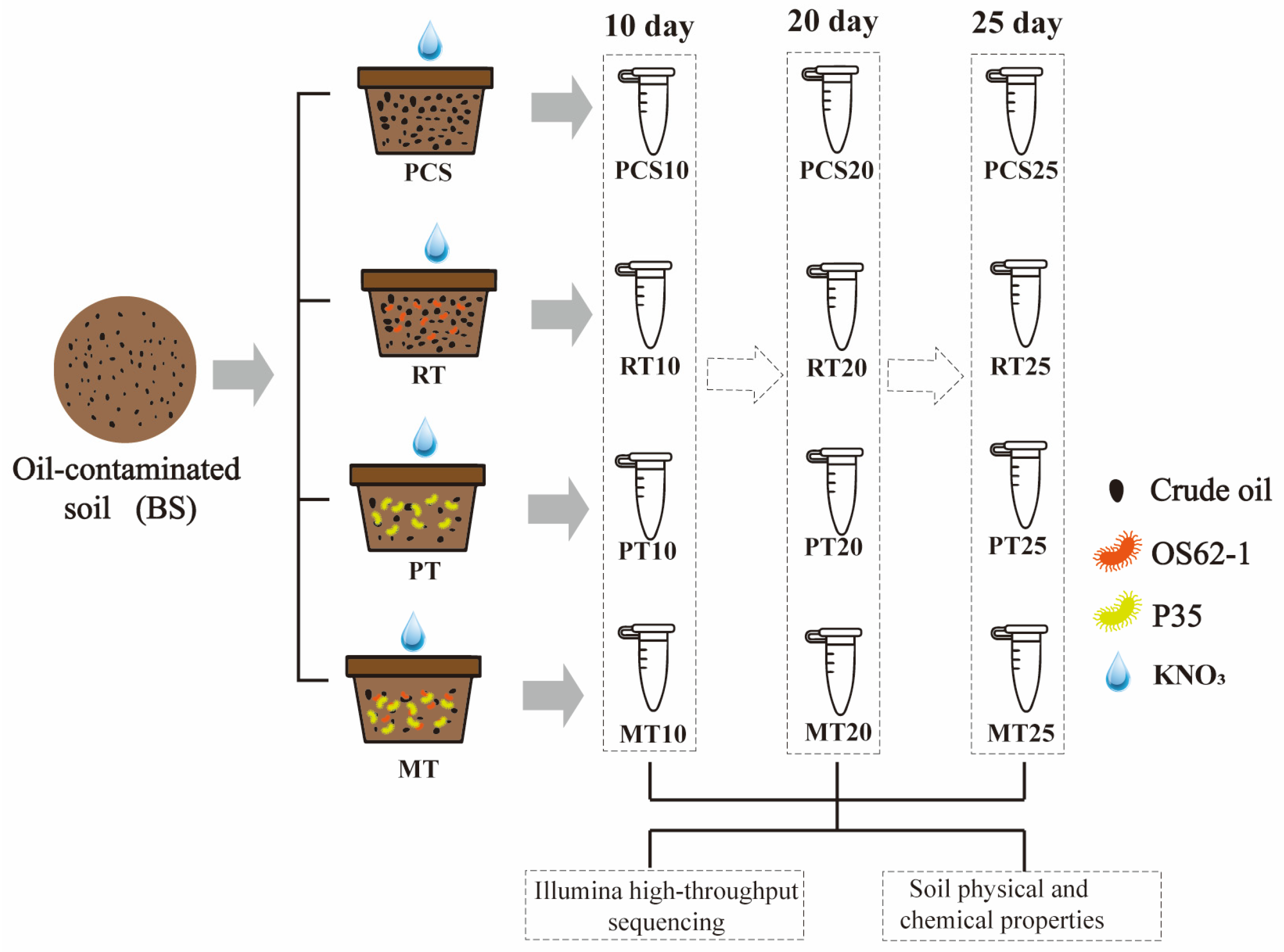

2.1. Experimental Designs

2.2. Experiment Design

2.3. Analysis of Soil Properties

2.4. Microbial Community Analysis

2.5. Analysis of Microbial Network

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Soil Physicochemical Parameters During Bioremediation

3.2. Soil Enzyme Activities

3.3. Microbial Composition and Diversity

3.3.1. Microbial Alpha Diversity

3.3.2. Microbial Community Structure

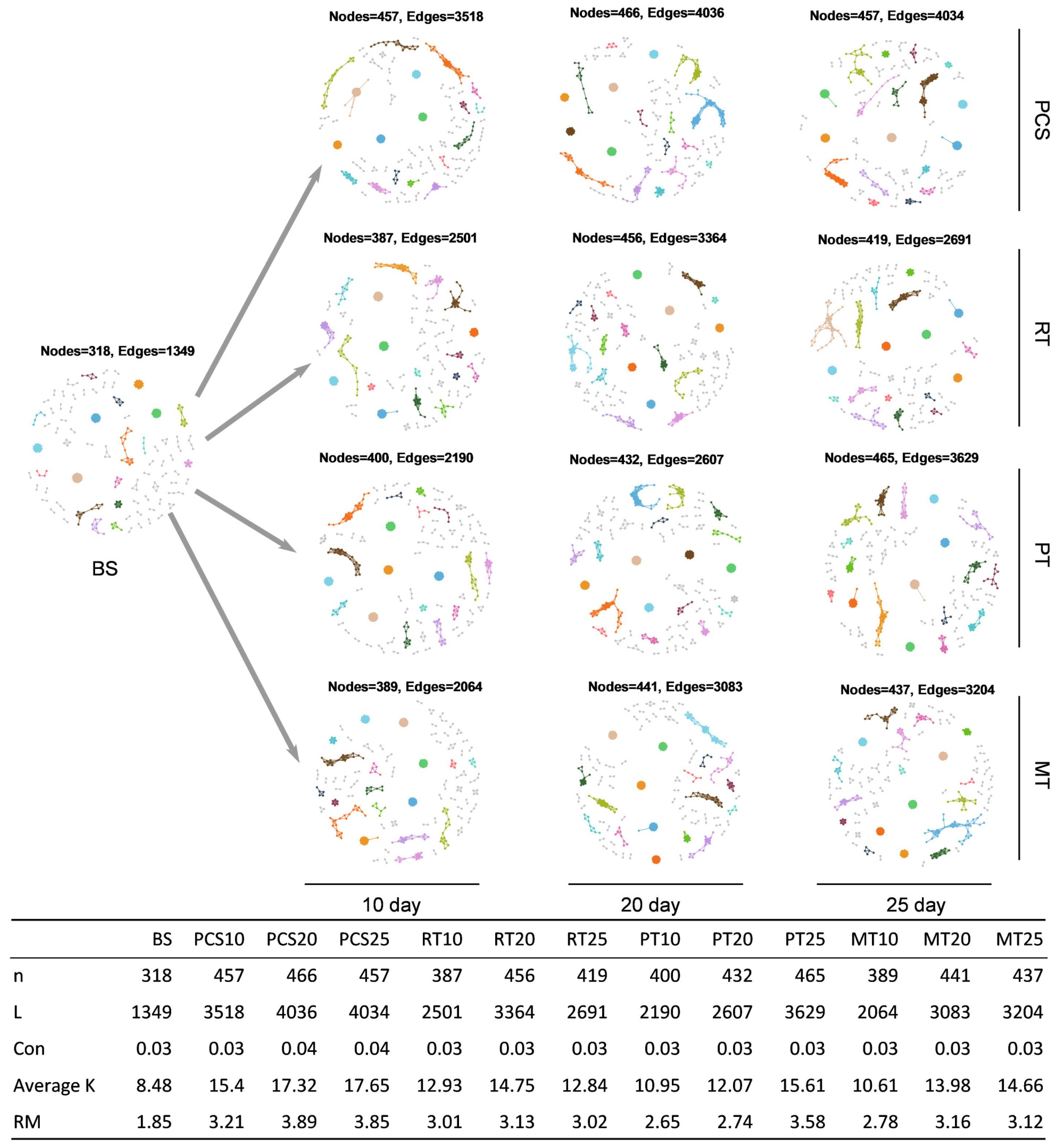

3.3.3. Microbial Networks Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gu, J.D.; Wang, Y.S. Coastal and marine pollution and ecotoxicology. Ecotoxicology 2015, 24, 1407–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukumar, B.; Al Salhi, M.S.; Narenkumar, J.; Devanesan, S.; Tentu Nageswara, R.; Kim, W.; Rajasekar, A. Characterization of two novel strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on biodegradation of crude oil and its enzyme activities. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 304, 119223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, P.; Parthipan, P.; Huang, M.; Muthukumar, B.; Cheng, L.; Govarthanan, M.; Rajasekar, A. Enhanced biodegradation of hydrophobic organic pollutants by the bacterial consortium: Impact of enzymes and biosurfactants. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varjani, S.; Upasani, V.N. Influence of abiotic factors, natural attenuation, bioaugmentation and nutrient supplementation on bioremediation of petroleum crude contaminated agricultural soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 245, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossai, I.C.; Ahmed, A.; Hassan, A.; Hamid, F.S. Remediation of soil and water contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbon: A review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 17, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govarthanan, M.; Ameen, F.; Kamala-Kannan, S.; Selvankumar, T.; Almansob, A.; Alwakeel, S.S.; Kim, W. Rapid biodegradation of chlorpyrifos by plant growth-promoting psychrophilic Shewanella sp. BT05: An eco-friendly approach to clean up pesticide-contaminated environment. Chemosphere 2020, 247, 125948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyukina, M.S.; Ivshina, I.B.; Kamenskikh, T.N.; Bulicheva, M.V.; Stukova, G.I. Survival of cryogel-immobilized Rhodococcus strains in crude oil-contaminated soil and their impact on biodegradation efficiency. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 84, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Guo, S.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Zeng, D.-H. Effects of different remediation treatments on crude oil contaminated saline soil. Chemosphere 2014, 117, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, Z.-Q.; Wang, M.; Yu, K.-F.; Zhang, T.; Lin, H.; Zheng, H.-B. Biodegradation of tylosin in swine wastewater by Providencia stuartii TYL-Y13: Performance, pathway, genetic background, and risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 440, 129716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaela Marilena, S. Investigating the Potential of Native Soil Bacteria for Diesel Biodegradation. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddhartha, P.; Arpita, H.; Sunanda, M.; Ajoy, R.; Pinaki, S.; Sufia, K.K. Crude oil degrading efficiency of formulated consortium of bacterial strains isolated from petroleum-contaminated sludge. 3 Biotech 2024, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorra, H.; Ahmed, R.R.; Raeid, M.M.A.; Nasser, A.; Ashraf, M.E.N.; Wael, I. Functional and structural responses of a halophilic consortium to oily sludge during biodegradation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Gong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, D.; Huang, X.; Yang, H. Bioaugmentation potential evaluation of a bacterial consortium composed of isolated Pseudomonas and Rhodococcus for degrading benzene, toluene and styrene in sludge and sewage. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 320, 124329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Kong, Y.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Min, J.; Hu, X. Enhanced biodegradation of crude oil by constructed bacterial consortium comprising salt-tolerant petroleum degraders and biosurfactant producers. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2020, 154, 105047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Sun, S.; Guo, X.; Luo, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Lei, T.; Leng, F.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y. Integration of physiology, genomics and microbiomics analyses reveal the biodegradation mechanism of petroleum hydrocarbons by Medicago sativa L. and growth-promoting bacterium Rhodococcus erythropolis KB1. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 415, 131659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Ma, J.; Huang, L.; Li, D.; Gao, G.; Zhao, Y.; Antunes, A.; Li, M. Biodegradation of crude oil and aniline by heavy metal-tolerant strain Rhodococcus sp. DH-2. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iminova, L.; Delegan, Y.; Frantsuzova, E.; Bogun, A.; Zvonarev, A.; Suzina, N.; Anbumani, S.; Solyanikova, I. Physiological and biochemical characterization and genome analysis of Rhodococcus qingshengii strain 7B capable of crude oil degradation and plant stimulation. Biotechnol. Rep. 2022, 35, e00741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binazadeh, M.; Li, Z.; Karimi, I.A. Optimization of Biodegradation of long chain n-alkanes by Rhodococcus sp. Moj-3449 using response surface methodology. Phys. Chem. Res. 2020, 8, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.Q.; He, Y.; Huang, L.; Jiang, D.W.; Lu, W.Y. n-Hexadecane and pyrene biodegradation and metabolization by Rhodococcus sp. T1 isolated from oil contaminated soil. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 27, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Liu, X.; Ai, J.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, X.; He, X.; Deng, Z.; Jiang, Y. Microbial community succession during crude oil-degrading bacterial enrichment cultivation and construction of a degrading consortium. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1044448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HJ 1051-2019; Soil—Determination of Petroleum Oil—Infrared Spectrophotometry. Ministry of Ecology and Environment the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- HJ 634-2012; Soil-Determination of Ammonium, Nitrite and Nitrate by Extraction with Potassium Chloride Solution—Spectrophotometric Methods. Ministry of Ecology and Environment the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- HJ 717-2014; Soil Quality-Determination of Total Nitrogen-Modified Kjeldahl. Ministry of Ecology and Environment the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnetjournal 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.M.; Guo, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, N.; Ning, D.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wu, L.; Yang, Y.; et al. Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Xie, P.; Yang, S.; Niu, G.; Liu, X.; Ding, Z.; Xue, C.; Liu, Y.X.; Shen, Q.; Yuan, J. ggClusterNet: An R package for microbiome network analysis and modularity-based multiple network layouts. iMeta 2022, 1, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varjani, S.; Upasani, V.N. Bioaugmentation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 5514-A novel oily waste degrader for treatment of petroleum hydrocarbons. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 319, 124240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varjani, S.; Upasani, V.N.; Pandey, A. Bioremediation of oily sludge polluted soil employing a novel strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and phytotoxicity of petroleum hydrocarbons for seed germination. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, A.B.; Karadzic, I.M. Pseudomonas in environmental bioremediation of hydrocarbons and phenolic compounds- key catabolic degradation enzymes and new analytical platforms for comprehensive investigation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 38, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Yuan, M.L.; Lei, L.Y.; Li, C.Y.; Xu, X.M. Enhanced production of mono-rhamnolipid in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and application potential in agriculture and petroleum industry. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 323, 124605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phulpoto, I.A.; Hu, B.W.; Wang, Y.F.; Ndayisenga, F.; Li, J.M.; Yu, Z.S. Effect of natural microbiome and culturable biosurfactants-producing bacterial consortia of freshwater lake on petroleum-hydrocarbon degradation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wang, M.X.; Geng, S.; Wen, L.Q.; Wu, M.D.; Nie, Y.; Tang, Y.Q.; Wu, X.L. Metabolic Exchange with Non-Alkane-Consuming Pseudomonas stutzeri SLG510A3-8 Improves n-Alkane Biodegradation by the Alkane Degrader Dietzia sp. Strain DQ12-45-1b. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e02931-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, M.; Gao, H.; Gao, J.; Wang, S. Application of 15N tracing and bioinformatics for estimating microbial-mediated nitrogen cycle processes in oil-contaminated soils. Environ. Res. 2023, 217, 114799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Hu, X. Nutrient depletion is the main limiting factor in the crude oil bioaugmentation process. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 100, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Wu, M.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Kang, H.; Hu, M.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X. Influence mechanisms underlying the degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons in response to various nitrogen dosages supplementation through metatranscriptomics analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 137074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappu, A.R.; Bhattacharjee, A.S.; Dasgupta, S.; Goel, R. Nitrogen cycle in engineered and natural ecosystems—Past and current. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2017, 3, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, A.; Sharma, S.; Semor, N.; Babele, P.K.; Sagar, S.; Bhatia, R.K.; Walia, A. Recent advancements in hydrocarbon bioremediation and future challenges: A review. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunyan, X.; Qaria, M.A.; Qi, X.; Daochen, Z. The role of microorganisms in petroleum degradation: Current development and prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 865, 161112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipińska, A.; Kucharski, J.; Wyszkowska, J. Urease activity in soil contaminated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 22, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel Chukwuma, O.; Kingsley, O.; Emmanuel, E.; Marshall Arebojie, A. Bio-augmentation and bio-stimulation with kenaf core enhanced bacterial enzyme activities during bio-degradation of petroleum hydrocarbon in polluted soil. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Fu, W.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Song, D. Synergetic effects of microbial-phytoremediation reshape microbial communities and improve degradation of petroleum contaminants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 429, 128396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Zhu, N.; Cui, J.; Wang, H.; Dang, Z.; Wu, P.; Li, Y.; Shi, C. Ecotoxicity monitoring and bioindicator screening of oil-contaminated soil during bioremediation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 124, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C.; Ostle, N.; Kang, H. An enzymic ‘latch’ on a global carbon store. Nature 2001, 409, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, L.; Zheng, X.; Oba, B.T.; Shen, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Luo, Q.; Sun, L. Activating soil microbial community using Bacillus and rhamnolipid to remediate TPH contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2021, 275, 130062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, L.; Shen, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Tang, J. Enhanced remediation of oil-contaminated intertidal sediment by bacterial consortium of petroleum degraders and biosurfactant producers. Chemosphere 2023, 330, 138763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, G.B.; Jared, L.D.; Jürgen, M.; Robert, L.S.; Mary, E.S.; Matthew, D.W.; Michael, W.; Annamaria, Z. Soil enzymes in a changing environment: Current knowledge and future directions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 58, 216–234. [Google Scholar]

- Maegala Nallapan, M.; Anupriya, S.; Hazeeq Hazwan, A.; Nor Suhaila, Y.; Hasdianty, A. Effect of inoculum size, inducer and metal ion on lipase production by Rhodococcus strain UCC 0009. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 211, 02012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maegala Nallapan, M.; Hazeeq Hazwan, A.; Hasdianty, A.; Nor Suhaila, Y. Conversion of waste cooking oil by rhodococcal lipase immobilized in gellan gum. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 277, 03011. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Wu, M.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z. Effect of petroleum hydrocarbon pollution levels on the soil microecosystem and ecological function. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; He, S.; Zhao, Y. Remediation of petroleum-contaminated soil by highly efficient oil-degrading bacteria and analysis of its enhancement mechanism. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2023, 44, 4599–4610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Unimke, A.; Mmuoegbulam, O.; Anika, O. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons: Realities, challenges and prospects. Biotechnol. J. Int. 2018, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Asmaa, A.H.; Mohamed, M.H. Biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons using indigenous bacterial and actinomycetes cultures. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 23, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, A.; Schumann, P.; Spröer, C. Nocardioides oleivorans sp. nov., a novel crude-oil-degrading bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1501–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, S.G.; Lee, C.; Kim, M.-K.; Kang, H.-J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, M.J.; Malik, A.; Kim, S.B. Nocardioides euryhalodurans sp. nov., Nocardioides seonyuensis sp. nov. and Nocardioides eburneiflavus sp. nov., isolated from soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2682–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Hu, M.; Huang, X.; Gao, H.; Wu, X. Differential microbial mechanisms of TPH degradation and detoxification during stepwise bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated soil. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patek, M.; Grulich, M.; Nesvera, J. Stress response in Rhodococcus strains. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 53, 107698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Qiao, Y.; Xue, J.; Cheng, D.; Chen, C.; Bai, Y.; Jiang, Q. Analyses of community structure and role of immobilized bacteria system in the bioremediation process of diesel pollution seawater. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 799, 149439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, N.; Duan, C.; Ding, C.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J. Biodegradable microplastics enhance soil microbial network complexity and ecological stochasticity. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 439, 129610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Residual Oil Content (mg) | TN (mg/kg) | -N (mg/kg) | -N (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS | 5345.02 ± 162.79 a | 634.69 ± 28.20 a | 553.08 ± 44.66 a | 7.69 ± 4.32 f |

| PCS10 | 4991.36 ± 114.77 b | 592.89 ± 18.84 ab | 526.91 ± 25.09 ab | 10.44 ± 5.81 f |

| PCS20 | 4371.80 ± 113.33 cd | 529.13 ± 12.98 c | 469.21 ± 37.98 bc | 24.58 ± 3.20 e |

| PCS25 | 4214.33 ± 122.71 d | 474.79 ± 17.32 d | 457.52 ± 30.09 c | 25.53 ± 3.87 e |

| PT10 | 4603.74 ± 119.04 c | 556.19 ± 29.26 bc | 473.26 ± 17.91 bc | 12.98 ± 2.39 f |

| PT20 | 3741.81 ± 141.54 e | 475.69 ± 19.61 d | 375.22 ± 24.18 d | 37.62 ± 4.83 d |

| PT25 | 3508.78 ± 192.59 e | 435.55 ± 20.23 de | 352.82 ± 24.99 d | 43.36 ± 5.62 cd |

| RT10 | 4224.30 ± 158.46 d | 454.11 ± 21.70 d | 371.01 ± 13.46 d | 16.48 ± 2.77 ef |

| RT20 | 2827.32 ± 167.51 f | 296.66 ± 17.06 f | 230.11 ± 22.08 e | 46.11 ± 3.60 bcd |

| RT25 | 2468.79 ± 148.22 g | 264.97 ± 25.21 fg | 173.39 ± 18.90 ef | 49.80 ± 4.25 abc |

| MT10 | 3638.95 ± 150.65 e | 387.33 ± 26.98 e | 341.47 ± 25.56 d | 39.87 ± 5.20 cd |

| MT20 | 2271.87 ± 137.63 gh | 229.72 ± 14.50 g | 152.61 ± 32.95 f | 54.11 ± 2.15 ab |

| MT25 | 1973.17 ± 169.29 h | 158.66 ± 15.17 h | 115.78 ± 15.71 f | 58.14 ± 6.62 a |

| Sample ID | Chao1 | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|

| BS | 523.0 ± 29.9 a | 8.5 ± 0.1 a | 0.99 ± 0.02 a |

| PCS10 | 450.2 ± 25.1 b | 6.4 ± 0.4 bc | 0.89 ± 0.03 bc |

| PCS20 | 424.4 ± 55.0 b | 5.9 ± 0.7 c | 0.87 ± 0.05 c |

| PCS25 | 422.8 ± 46.6 b | 6.1 ± 0.5 bc | 0.90 ± 0.03 bc |

| RT10 | 471.0 ± 50.7 ab | 6.8 ± 0.3 b | 0.92 ± 0.02 b |

| RT20 | 441.8 ± 32.0 b | 6.3 ± 0.3 bc | 0.90 ± 0.02 bc |

| RT25 | 457.2 ± 16.8 ab | 6.7 ± 0.2 b | 0.94 ± 0.01 b |

| PT10 | 482.0 ± 29.7 ab | 6.7 ± 0.2 b | 0.91 ± 0.01 b |

| PT20 | 460.2 ± 52.5 ab | 6.3 ± 0.5 bc | 0.90 ± 0.03 bc |

| PT25 | 426.8 ± 34.6 b | 6.4 ± 0.4 bc | 0.92 ± 0.02 bc |

| MT10 | 463.2 ± 16.9 ab | 6.3 ± 0.2 bc | 0.90 ± 0.02 bc |

| MT20 | 427.6 ± 41.4 b | 6.1 ± 0.5 bc | 0.90 ± 0.04 bc |

| MT25 | 430.0 ± 13.8 b | 6.5 ± 0.1 bc | 0.93 ± 0.01 bc |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Deng, Z.; He, X. Microbial Community Succession During Bioremediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soils Using Rhodococcus sp. OS62-1 and Pseudomonas sp. P35. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010007

Liu X, Ma Y, Jiang Y, Guo Y, Deng Z, He X. Microbial Community Succession During Bioremediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soils Using Rhodococcus sp. OS62-1 and Pseudomonas sp. P35. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiaodong, Yuxi Ma, Yingying Jiang, Yidan Guo, Zhenshan Deng, and Xiaolong He. 2026. "Microbial Community Succession During Bioremediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soils Using Rhodococcus sp. OS62-1 and Pseudomonas sp. P35" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010007

APA StyleLiu, X., Ma, Y., Jiang, Y., Guo, Y., Deng, Z., & He, X. (2026). Microbial Community Succession During Bioremediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soils Using Rhodococcus sp. OS62-1 and Pseudomonas sp. P35. Microorganisms, 14(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010007