Estimating Postmortem Interval of Buried Pig Carcasses by Integrating Microbial Succession Patterns with Machine Learning Algorithms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Sample Collection

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

2.4. Developing PMI Estimation Models

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Decomposition

3.2. Sequencing Results

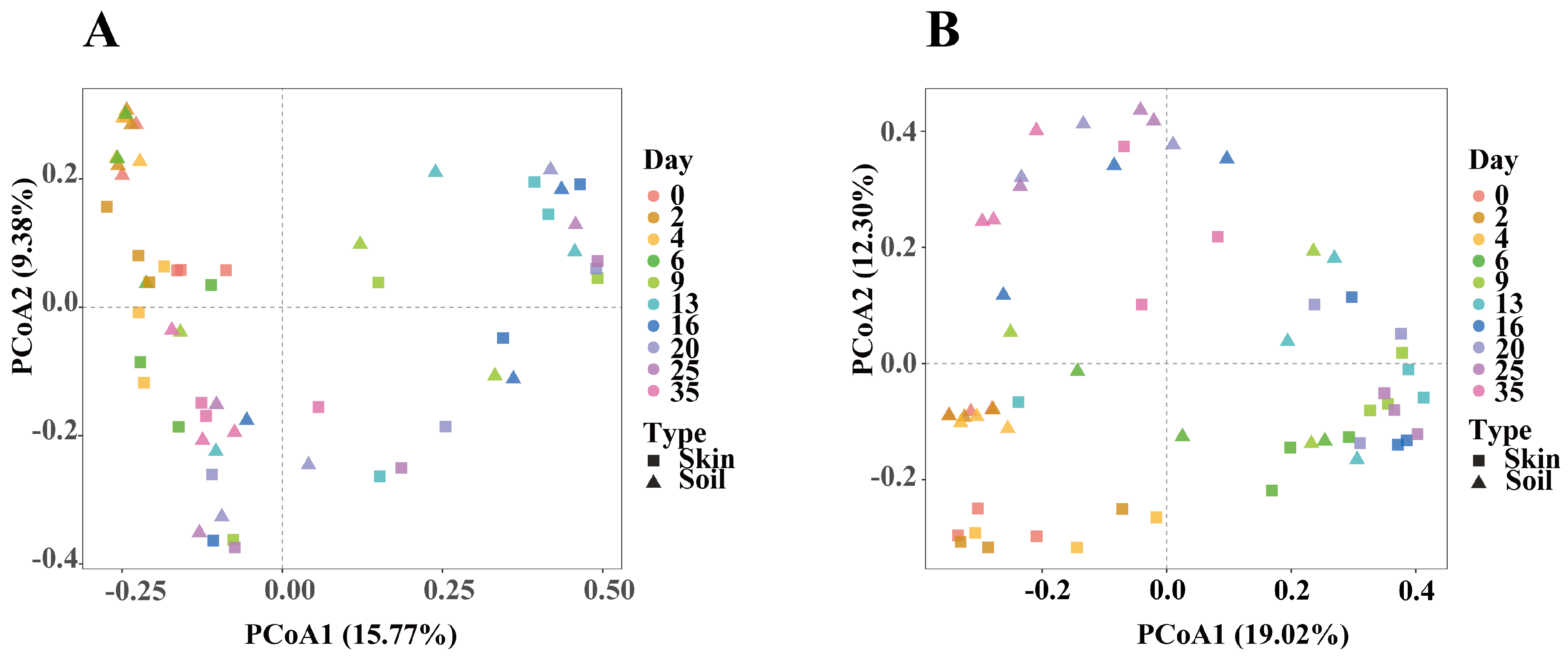

3.3. Bacterial Community Diversity Analysis

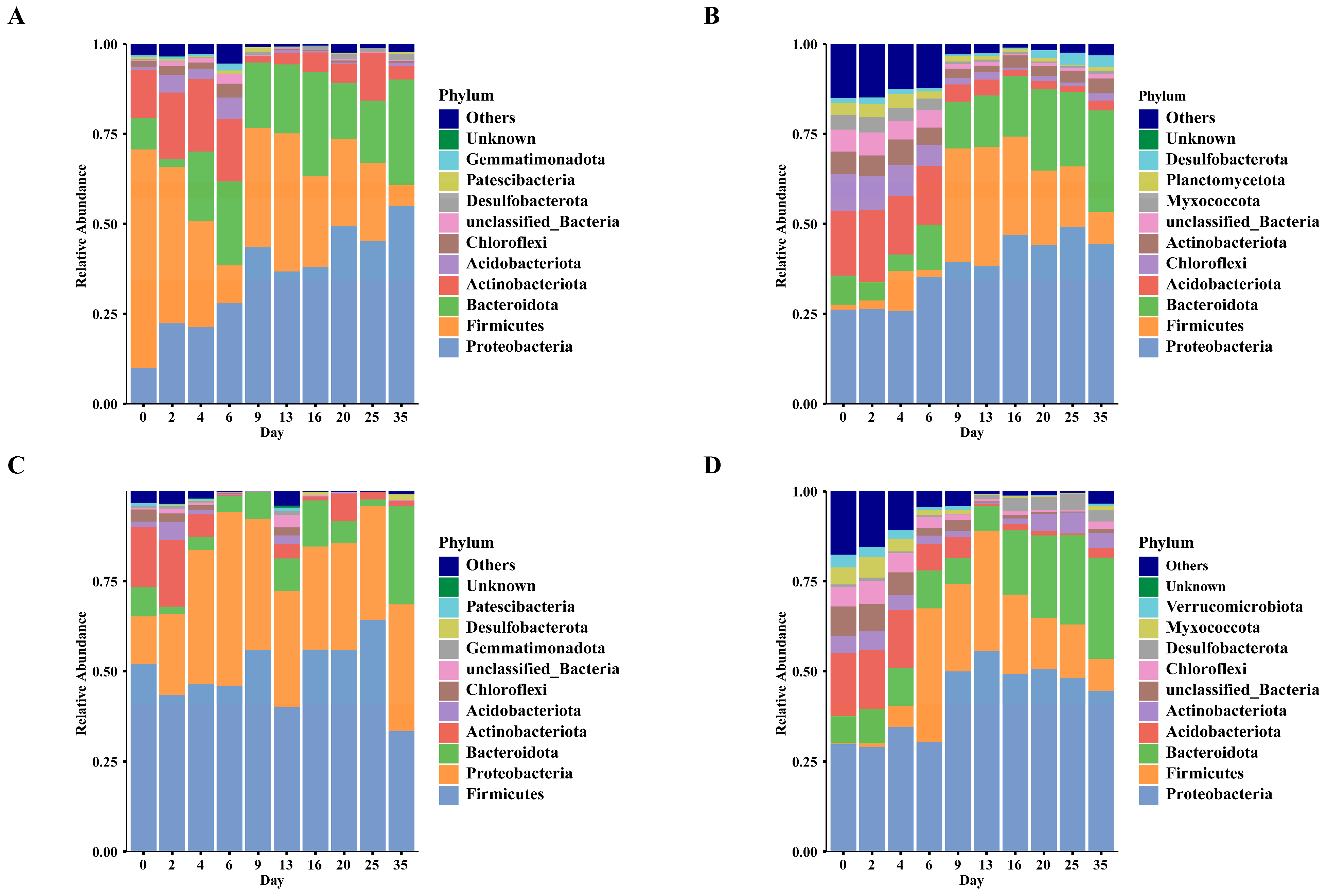

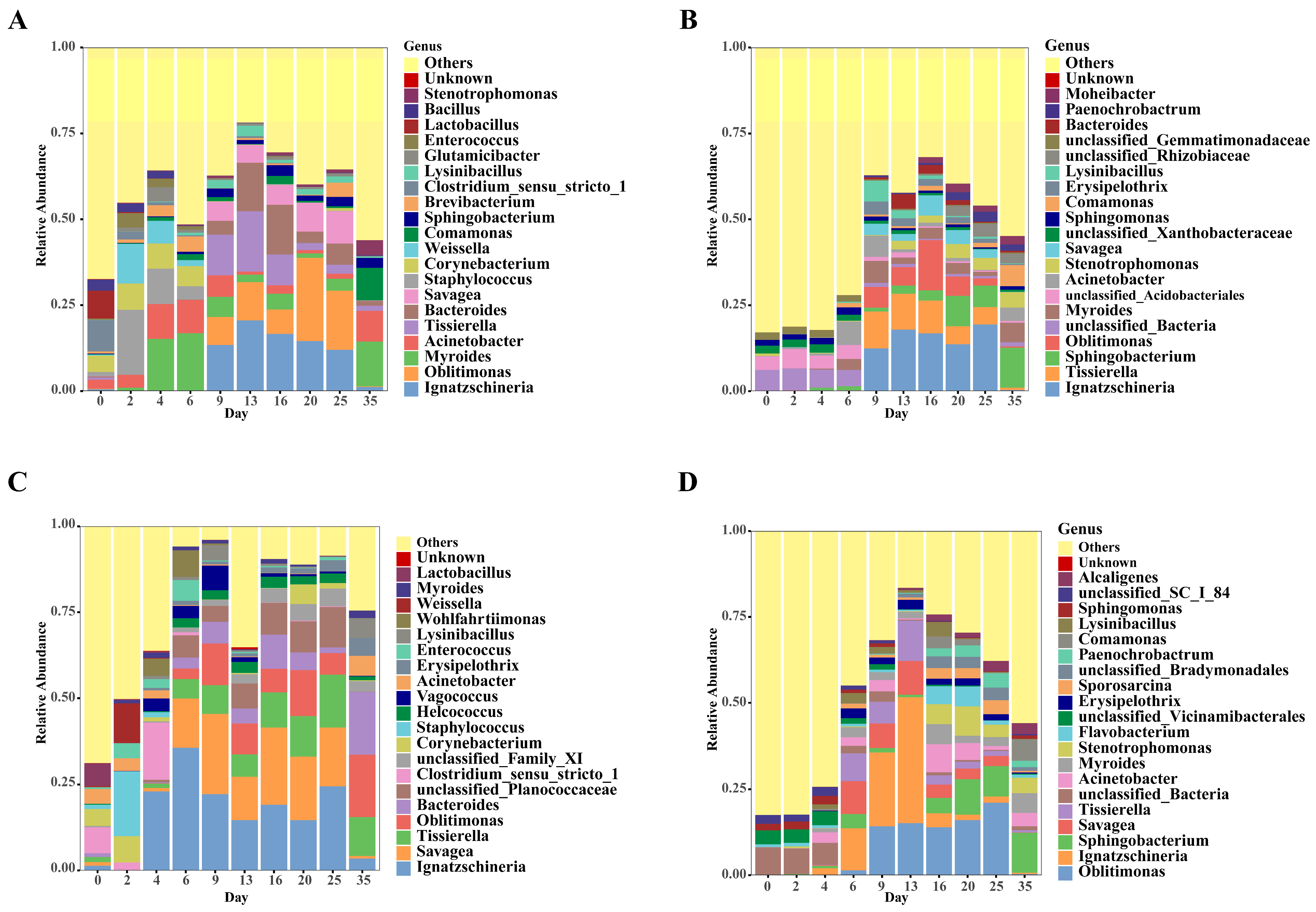

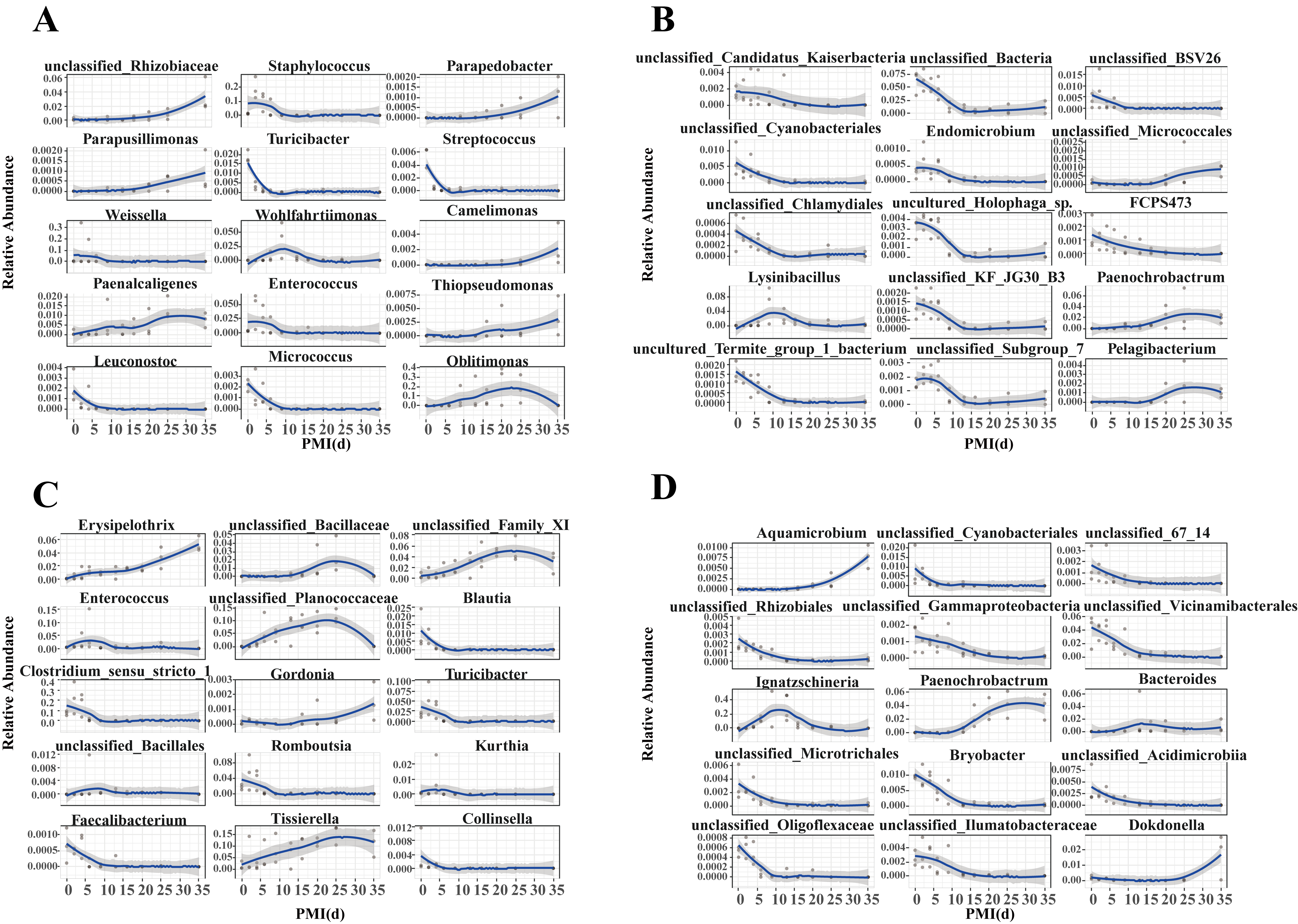

3.4. Temporal Changes in Bacterial Community Composition of Carcasses

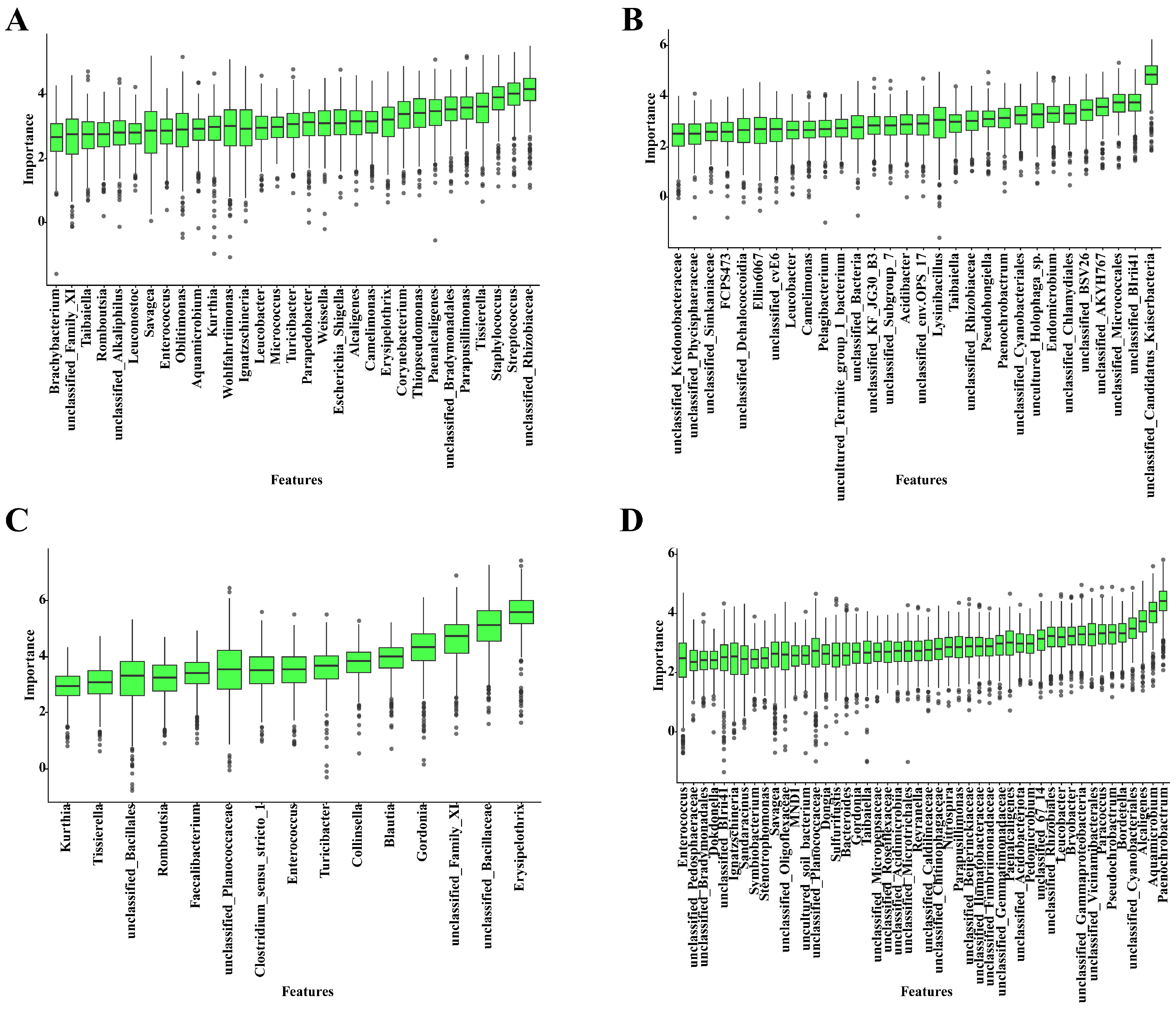

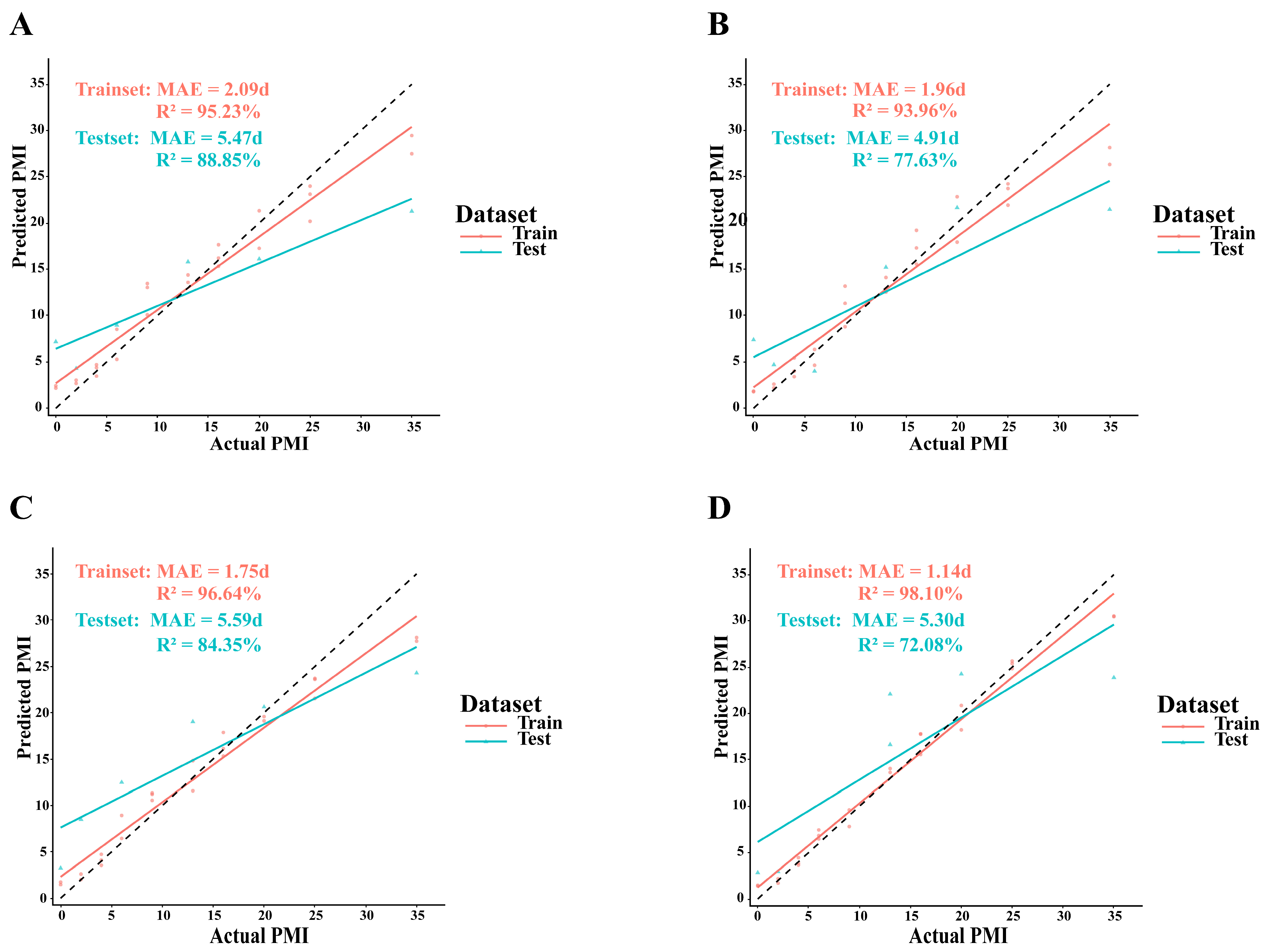

3.5. PMI Estimation Models Based on Skin and Soil Succession

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Niu, Y. Research Progress of DNA-Based Technologies for Postmortem Interval Estimation. J. Forensic Med. 2022, 38, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggenthaler, H.; Sinicina, I.; Hubig, M.; Mall, G. Database of post-mortem rectal cooling cases under strictly controlled conditions: A useful tool in death time estimation. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2012, 126, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Giorgio, F.; Ciasca, G.; Fecondo, G.; Mazzini, A.; De Spirito, M.; Pascali, V.L. Estimation of the time of death by measuring the variation of lateral cerebral ventricle volume and cerebrospinal fluid radiodensity using postmortem computed tomography. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Soni, S.; White, J.; Can, G.; Javan, G.T. Evaluation of DNA degradation using flow cytometry: Promising tool for postmortem interval determination. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2015, 36, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendt, J.; Richards, C.S.; Campobasso, C.P.; Zehner, R.; Hall, M.J. Forensic entomology: Applications and limitations. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2011, 7, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.L.; Guo, J.J.; Liu, Z.Y.; Shen, X.; Cai, J.F. Application of High-throughput Sequencing in Researches of Cadaveric Microorganisms and Postmortem Interval Estimation. J. Forensic Med. 2018, 34, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashe, E.C.; Comeau, A.M.; Zejdlik, K.; O’Connell, S.P. Characterization of Bacterial Community Dynamics of the Human Mouth Throughout Decomposition via Metagenomic, Metatranscriptomic, and Culturing Techniques. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 689493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, A.L.; Mundorff, A.Z.; Hoeland, K.M.; Davoren, J.; Keenan, S.W.; Carter, D.O.; Campagna, S.R.; DeBruyn, J.M. Postmortem Skeletal Microbial Community Composition and Function in Buried Human Remains. mSystems 2022, 7, e0004122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, E.R.; Haarmann, D.P.; Lynne, A.M.; Bucheli, S.R.; Petrosino, J.F. The living dead: Bacterial community structure of a cadaver at the onset and end of the bloat stage of decomposition. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.O.; Metcalf, J.L.; Bibat, A.; Knight, R. Seasonal variation of postmortem microbial communities. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2015, 11, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.W.; Schrijver, I. Next generation DNA sequencing and the future of genomic medicine. Genes 2010, 1, 38–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalf, J.L.; Parfrey, L.W.; Gonzalez, A.; Lauber, C.L.; Knights, D.; Ackermann, G.; Humphrey, G.C.; Gebert, M.J.; Van Treuren, W.; Berg-Lyons, D.; et al. A microbial clock provides an accurate estimate of the postmortem interval in a mouse model system. eLife 2013, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.R.; Trinidad, D.D.; Guzman, S.; Khan, Z.; Parziale, J.V.; DeBruyn, J.M.; Lents, N.H. A Machine Learning Approach for Using the Postmortem Skin Microbiome to Estimate the Postmortem Interval. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobaugh, K.L.; Schaeffer, S.M.; DeBruyn, J.M. Functional and Structural Succession of Soil Microbial Communities below Decomposing Human Cadavers. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.; Carter, D.O.; Metcalf, J.L.; Knight, R. Carcass mass has little influence on the structure of gravesoil microbial communities. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2016, 130, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procopio, N.; Ghignone, S.; Voyron, S.; Chiapello, M.; Williams, A.; Chamberlain, A.; Mello, A.; Buckley, M. Soil Fungal Communities Investigated by Metabarcoding Within Simulated Forensic Burial Contexts. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, C.; Song, Y.; Mao, D.; Cao, Y.; Qiu, B.; Gui, P.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Z.; Sun, L.; et al. Predicting the Postmortem Interval Based on Gravesoil Microbiome Data and a Random Forest Model. Microorganisms 2022, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauther, K.A.; Cobaugh, K.L.; Jantz, L.M.; Sparer, T.E.; DeBruyn, J.M. Estimating Time Since Death from Postmortem Human Gut Microbial Communities. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Fu, X.; Liao, H.; Hu, Z.; Long, L.; Yan, W.; Ding, Y.; Zha, L.; Guo, Y.; Yan, J.; et al. Potential use of bacterial community succession for estimating post-mortem interval as revealed by high-throughput sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Qi, X.; Shi, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Ren, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, G.; et al. Predicting the postmortem interval of burial cadavers based on microbial community succession. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2021, 52, 102488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, X.; Hu, S.; Nie, H.; Gui, P.; Zhong, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, X. Changes in Microbial Communities Using Pigs as a Model for Postmortem Interval Estimation. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, J.L. Estimating the postmortem interval using microbes: Knowledge gaps and a path to technology adoption. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2019, 38, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Simayijiang, H.; Hu, P.; Yan, J. Application of Microbiome in Forensics. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2023, 21, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, J.L.; Xu, Z.Z.; Weiss, S.; Lax, S.; Van Treuren, W.; Hyde, E.R.; Song, S.J.; Amir, A.; Larsen, P.; Sangwan, N.; et al. Microbial community assembly and metabolic function during mammalian corpse decomposition. Science 2016, 351, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Le, C.; Jin, X.; Feng, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, X.; Tian, S.; Wang, Q.; Ji, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Estimating postmortem interval based on oral microbial community succession in rat cadavers. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, S.; Graw, M. Decomposition of buried corpses, with special reference to the formation of adipocere. Naturwissenschaften 2003, 90, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, D.O.; Yellowlees, D.; Tibbett, M. Cadaver decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems. Naturwissenschaften 2007, 94, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Gu, Y.; Shen, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Q.; Wei, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, D.; Yu, K.; et al. Predicting postmortem interval based on microbial community sequences and machine learning algorithms. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 2273–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, R.; Yuan, L.; Wu, D.; Yang, E.; Yang, H.; Ullah, S.; Ishaq, H.M.; Liu, H.; et al. Potential use of molecular and structural characterization of the gut bacterial community for postmortem interval estimation in Sprague Dawley rats. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, S.J.; Pechal, J.L.; Benbow, M.E.; Robertson, B.K.; Javan, G.T. Microbial Signatures of Cadaver Gravesoil During Decomposition. Microb. Ecol. 2016, 71, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch, L.F.; Fulthorpe, R.R.; Riva, A.; Casella, G.; Hadwin, A.K.; Kent, A.D.; Daroub, S.H.; Camargo, F.A.; Farmerie, W.G.; Triplett, E.W. Pyrosequencing enumerates and contrasts soil microbial diversity. ISME J. 2007, 1, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.H.; Pollard, K.S. Proteobacteria explain significant functional variability in the human gut microbiome. Microbiome 2017, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Rastogi, G.; Nayduch, D.; Sawant, S.S.; Bhonde, R.R.; Shouche, Y.S. Molecular phylogenetic profiling of gut-associated bacteria in larvae and adults of flesh flies. Med. Vet. Entomol 2014, 28, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Crippen, T.L.; Zheng, L.; Fields, A.T.; Yu, Z.; Ma, Q.; Wood, T.K.; Dowd, S.E.; Flores, M.; Tomberlin, J.K.; et al. A metagenomic assessment of the bacteria associated with Lucilia sericata and Lucilia cuprina (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knights, D.; Costello, E.K.; Knight, R. Supervised classification of human microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Ouyang, J.; Chen, H.L.; Zhao, X.H. An efficient diagnosis system for Parkinson’s disease using kernel-based extreme learning machine with subtractive clustering features weighting approach. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2014, 2014, 985789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pechal, J.L.; Schmidt, C.J.; Jordan, H.R.; Wang, W.W.; Benbow, M.E.; Sze, S.H.; Tarone, A.M. Machine learning performance in a microbial molecular autopsy context: A cross-sectional postmortem human population study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, Y.L.; Li, H.Q.; Zhu, L.P.; Ali, S.; Yang, Z.G. The linear random forest algorithm and its advantages in machine learning assisted logging regression modeling. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 174, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, A.; Xu, Z.Z.; Carter, D.O.; Lynne, A.; Bucheli, S.; Knight, R.; Metcalf, J.L. Microbiome Data Accurately Predicts the Postmortem Interval Using Random Forest Regression Models. Genes 2018, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madea, B. Methods for determining time of death. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2016, 12, 451–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschetti, L.; Amadasi, A.; Bugelli, V.; Bolsi, G.; Tsokos, M. Estimation of Late Postmortem Interval: Where Do We Stand? A Literature Review. Biology 2023, 12, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewski, S. Post-Mortem Interval Estimation Based on Insect Evidence: Current Challenges. Insects 2021, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adserias-Garriga, J.; Quijada, N.M.; Hernandez, M.; Rodríguez Lázaro, D.; Steadman, D.; Garcia-Gil, L.J. Dynamics of the oral microbiota as a tool to estimate time since death. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2017, 32, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBruyn, J.M.; Hauther, K.A. Postmortem succession of gut microbial communities in deceased human subjects. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Xing, Y.; Jiang, P.; Gan, L.; Zhao, F.; Peng, W.; Li, W.; Tong, Y.; Deng, S. Predicting the postmortem interval using human intestinal microbiome data and random forest algorithm. Sci. Justice J. Forensic Sci. Soc. 2021, 61, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, T.; Chen, X.; Xie, Q.; Cai, J. Estimating Postmortem Interval of Buried Pig Carcasses by Integrating Microbial Succession Patterns with Machine Learning Algorithms. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010006

Yang T, Chen X, Xie Q, Cai J. Estimating Postmortem Interval of Buried Pig Carcasses by Integrating Microbial Succession Patterns with Machine Learning Algorithms. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Ting, Xudong Chen, Qihua Xie, and Jifeng Cai. 2026. "Estimating Postmortem Interval of Buried Pig Carcasses by Integrating Microbial Succession Patterns with Machine Learning Algorithms" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010006

APA StyleYang, T., Chen, X., Xie, Q., & Cai, J. (2026). Estimating Postmortem Interval of Buried Pig Carcasses by Integrating Microbial Succession Patterns with Machine Learning Algorithms. Microorganisms, 14(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010006