Influence of Pseudomonas sp. NEEL19 Expelled Volatile Compounds on Growth and Development of Crop Seedlings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Halotolerant Bacterial Strain and Seeds

2.2. Growth Analysis of Mung Bean and Fenugreek Seedlings Under NEEL19 (NEEL19 V+) Volatile Exposure

2.3. NEEL19 Volatilome Investigation

2.3.1. Identification of NEEL19 VOCs by SPME-GCMS

2.3.2. Assessment of VICs Released by NEEL19

2.4. Analysis of Mung Bean and Fenugreek Growth in PPD Exposed to Aqueous Ammonium Hydroxide Vapor (NH4OH)

2.5. Chlorophyll Content Measurement

2.6. Morphometric Analysis of Mung Bean Cotyledonary Leaf Stomata

2.7. Statistical Analysis and Software

3. Results

3.1. The Influence of NEEL19 V+ on the Development of Mung Bean and Fenugreek Seedlings

3.2. Volatilome Analysis of NEEL19

3.2.1. VOCs Profiling

3.2.2. Analysis of VICs

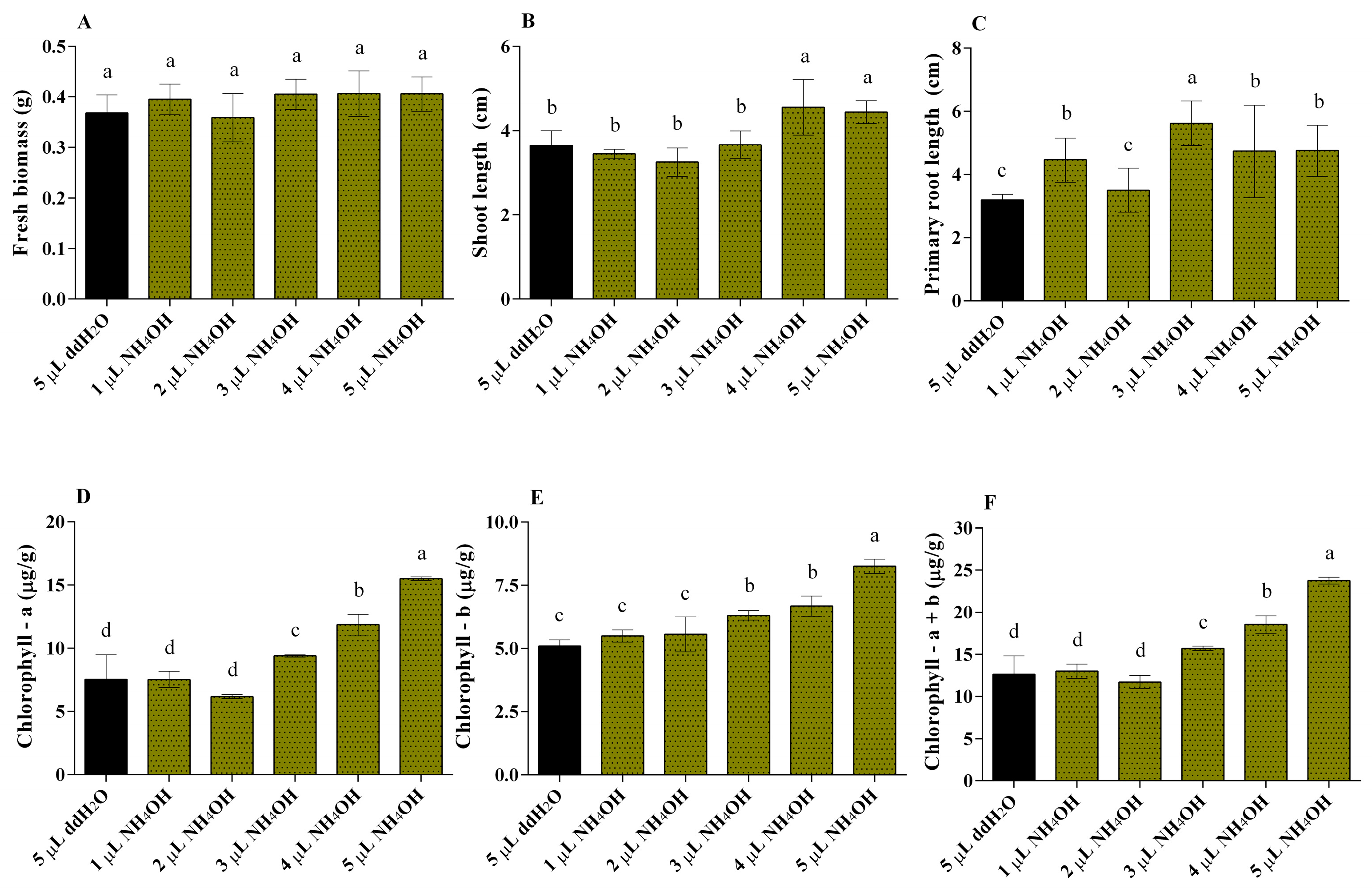

3.3. Influence of Mung Bean and Fenugreek Growth upon Aqueous NH4OH Exposure in PPD

3.4. Morphological Alterations in the Seedling’s Stomata of Mung Bean Subjected to NEEL19 V+ and NH4OH

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turner, T.R.; Ramakrishnan, K.; Walshaw, J.; Heavens, D.; Alston, M.; Swarbreck, D.; Osbourn, A.; Grant, A.; Poole, P.S. Comparative metatranscriptomics reveals kingdom level changes in the rhizosphere microbiome of plants. ISME J. 2013, 7, 2248–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, R.; Ryu, C.-M. Sniffing bacterial volatile compounds for healthier plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 44, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchiswamy, C.N.; Malnoy, M.; Maffei, M.E. Chemical diversity of microbial volatiles and their potential for plant growth and productivity. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzker, T.; Shepherdson, E.M.F.; Zambri, M.P.; Elliot, M.A. Bacterial volatile compounds: Functions in communication, cooperation, and competition. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 74, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Etalo, D.W.; de Jager, V.; Gerards, S.; Zweers, H.; de Boer, W.; Garbeva, P. Microbial small talk: Volatiles in fungal–bacterial interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisskopf, L.; Schulz, S.; Garbeva, P. Microbial volatile organic compounds in intra-kingdom and inter-kingdom interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, R.; Cordovez, V.; de Boer, W.; Raaijmakers, J.; Garbeva, P. Volatile affairs in microbial interactions. ISME J. 2015, 9, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz-Bohm, K.; Martín-Sánchez, L.; Garbeva, P. Microbial volatiles: Small molecules with an important role in intra- and inter-kingdom interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemfack, M.C.; Gohlke, B.-O.; Toguem, S.M.T.; Preissner, S.; Piechulla, B.; Preissner, R. mVOC 2.0: A database of microbial volatiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D1261–D1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda, J. Beneficial effects of microbial volatile organic compounds (MVOCs) in plants. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 168, 104118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raio, A. Diverse roles played by “Pseudomonas fluorescens complex” volatile compounds in their interaction with phytopathogenic microrganims, pests and plants. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, A.; Groenhagen, U.; Schulz, S.; Geisler, M.; Eberl, L.; Weisskopf, L. The inter-kingdom volatile signal indole promotes root development by interfering with auxin signalling. Plant J. 2014, 80, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloch, F.B.; Zeng, N.; Gong, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Baloch, S.B.; Ali, S.; Li, B. Rhizobacterial volatile organic compounds: Implications for agricultural ecosystems’ nutrient cycling and soil health. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledger, T.; Rojas, S.; Timmermann, T.; Pinedo, I.; Poupin, M.J.; Garrido, T.; Richter, P.; Tamayo, J.; Donoso, R. Volatile-mediated effects predominate in Paraburkholderia phytofirmans growth promotion and salt stress tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Tian, Y.; Jia, M.; Lu, X.; Yue, L.; Zhao, X.; Jin, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z.; et al. Induction of salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana by volatiles From Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 via the jasmonic acid signaling pathway. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 562934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.-S.; Dutta, S.; Ann, M.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Park, K. Promotion of plant growth by Pseudomonas fluorescens strain SS101 via novel volatile organic compounds. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 461, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhong, T.; Chen, X.; Yang, B.; Du, M.; Wang, K.; Zalán, Z.; Kan, J. Potential of volatile organic compounds emitted by Pseudomonas fluorescens ZX as biological fumigants to control citrus green mold decay at postharvest. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 2087–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effmert, U.; Kalderás, J.; Warnke, R.; Piechulla, B. Volatile mediated interactions between bacteria and fungi in the soil. J. Chem. Ecol. 2012, 38, 665–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Li, Z.; Yu, D. Bacillus megaterium strain XTBG34 promotes plant growth by producing 2-pentylfuran. J. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, M.; Piechulla, B. Plant growth promotion due to rhizobacterial volatiles—An effect of CO2? FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 3473–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, M.; Yan, Z.; Wang, F.; Yuan, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, L.; Tian, H.; Ding, Z. CO2 is a key constituent of the plant growth-promoting volatiles generated by bacteria in a sealed system. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, D.; Fabbri, C.; Eberl, L.; Weisskopf, L. Volatile-mediated killing of Arabidopsis thaliana by bacteria Is mainly due to hydrogen cyanide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, R.J.; Souissi, T. Cyanide production by Rhizobacteria and potential for suppression of weed seedling growth. Curr. Microbiol. 2001, 43, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohil, R.B.; Raval, V.H.; Panchal, R.R.; Rajput, K.N. Plant growth-promoting activity of Bacillus sp. PG-8 isolatedf from fermented panchagavya and its effect on the growth of Arachis hypogea. Front. Agron. 2022, 4, 805454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.P.G.C.; Pires, C.; Moreira, H.; Rangel, A.O.S.S.; Castro, P.M.L. Assessment of the plant growth promotion abilities of six bacterial isolates using Zea mays as indicator plant. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijland, R.; Burgess, J.G. Bacterial olfaction. Biotechnol. J. 2010, 5, 974–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAli, H.A.; Khalifa, A.; Almalki, M. Plant growth-promoting bacterium from non-agricultural soil improves okra plant growth. Agriculture 2022, 12, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré-Armengol, G.; Filella, I.; Llusia, J.; Peñuelas, J. Bidirectional interaction between phyllospheric microbiotas and plant volatile emissions. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Pandey, S. ACC deaminase producing bacteria with multifarious plant growth promoting traits alleviates salinity stress in french bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) plants. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Nguyen, D.H.; Lin, S.-Y.; Stothard, P.; Neelakandan, P.; Young, L.-S.; Young, C.-C. Hormesis of glyphosate on ferulic acid metabolism and antifungal volatile production in rice root biocontrol endophyte Burkholderia cepacia LS-044. Chemosphere 2023, 345, 140511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIST 2020. Qualitative Retention Time Index Std, RESTEK (USA). NIST Chemistry Webbook. Available online: https://sciencesolutions.wiley.com/wiley-releases-the-wiley-registry-12th-edition-nist-2020-mass-spectral-library-with-over-2-million-ei-and-lc-ms-spectra/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Abdelwahed, S.; Trabelsi, E.; Saadouli, I.; Kouidhi, S.; Masmoudi, A.S.; Cherif, A.; Mnif, W.; Mosbah, A. A new pioneer colorimetric micro-plate method for the estimation of ammonia production by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). Main Group Chem. 2022, 21, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, S.P.; Létoffé, S.; Delepierre, M.; Ghigo, J.M. Biogenic ammonia modifies antibiotic resistance at a distance in physically separated bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 81, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, M.; Karunakaran, K.; Nallasamy, P.; Moon, I.S. Effective identification of (NH4)2CO3 and NH4HCO3 concentrations in NaHCO3 regeneration process from desulfurized waste. Talanta 2015, 132, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Yiming, Z.; Qin, J.G.; Weizhi, Y.; Ma, Z. Optimization of the method for chlorophyll extraction in aquatic plants. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2010, 25, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, H.; Chehrazi, M.; Nabati Ahmadi, D.; Mahmoodi Sorestani, M. Colchicine-induced autotetraploidy and altered plant cytogenetic and morpho-physiological traits in Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 2018, 32, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldau, D.G.; Meldau, S.; Hoang, L.H.; Underberg, S.; Wünsche, H.; Baldwin, I.T. Dimethyl disulfide produced by the naturally associated bacterium Bacillus sp. B55 promotes Nicotiana attenuata growth by enhancing sulfur nutrition. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2731–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunziker, L.; Bönisch, D.; Groenhagen, U.; Bailly, A.; Schulz, S.; Weisskopf, L. Pseudomonas strains naturally associated with potato plants produce volatiles with high potential for inhibition of Phytophthora infestans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jishma, P.; Hussain, N.; Chellappan, R.; Rajendran, R.; Mathew, J.; Radhakrishnan, E.K. Strain-specific variation in plant growth promoting volatile organic compounds production by five different Pseudomonas spp. as confirmed by response of Vigna radiata seedlings. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, O.A.C.; de Araujo, N.O.; Mulato, A.T.N.; Persinoti, G.F.; Sforça, M.L.; Calderan-Rodrigues, M.J.; Oliveira, J.V.d.C. Bacterial volatile organic compounds (VOCs) promote growth and induce metabolic changes in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1056082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorholt, J.A. Microbial life in the phyllosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, R.; Fujinawa, Y.; Mine, A. Toward a plant biotechnological application of phyllosphere bacteria. Plant Biotechnol. 2025, 42, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelakandan, P.; Young, C.C.; Hameed, A.; Wang, Y.N.; Chen, K.N.; Shen, F.T. Volatile 1-octanol of tea (Camellia sinensis L.) fuels cell division and indole-3-acetic acid production in phylloplane isolate Pseudomonas sp. NEEL19. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, S.S.; Cappellari, L.d.R.; Giordano, W.; Banchio, E. Antifungal activity and alleviation of salt stress by volatile organic compounds of native Pseudomonas obtained from Mentha piperita. Plants 2023, 12, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, H.; Rashid, U.; Hassan, M.N.; Nosheen, A.; Naz, R.; Ilyas, N.; Sajjad, M.; Azmat, A.; Alyemeni, M.N. Volatile organic compounds produced by alleviated drought stress by modulating defense system in maize (Zea mays L.). Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 896–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.-S.; Wu, H.-J.; Zang, H.-Y.; Wu, L.-M.; Zhu, Q.-Q.; Gao, X.-W. Plant growth promotion by spermidine-producing Bacillus subtilis OKB105. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2014, 27, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xie, X.; Kim, M.-S.; Kornyeyev, D.A.; Holaday, S.; Paré, P.W. Soil bacteria augment Arabidopsis photosynthesis by decreasing glucose sensing and abscisic acid levels in planta. Plant J. 2008, 56, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, C.M.; Farag, M.A.; Hu, C.H.; Reddy, M.S.; Wei, H.X.; Paré, P.W.; Kloepper, J.W. Bacterial volatiles promote growth in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4927–4932, Erratum in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, H.A.S.; Gu, Q.; Wu, H.; Raza, W.; Safdar, A.; Huang, Z.; Rajer, F.U.; Gao, X. Effect of volatile compounds produced by Ralstonia solanacearum on plant growth promoting and systemic resistance inducing potential of Bacillus volatiles. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, S.; Holland, L.; Morrin, A. An investigation of stability and species and strain-level specificity in bacterial volatilomes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 693075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, C.L.; Bean, H.D. Dependence of the Staphylococcal volatilome composition on microbial nutrition. Metabolites 2020, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, M.; Effmert, U.; Piechulla, B. Bacterial-plant-interactions: Approaches to unravel the biological function of bacterial volatiles in the rhizosphere. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asari, S.; Matzén, S.; Petersen, M.A.; Bejai, S.; Meijer, J. Multiple effects of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens volatile compounds: Plant growth promotion and growth inhibition of phytopathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Tang, J.; Shi, H.; Tang, C.; Zhang, R. Characteristics of volatile organic compounds produced from five pathogenic bacteria by headspace-solid phase micro-extraction/gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Basic Microbiol. 2017, 57, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rashdi, A.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Al-Harrasi, M.M.A.; Al-Sabahi, J.N.; Janke, R.; Velazhahan, R. The effect of NaCl on growth and volatile metabolites produced by antagonistic endophytic bacteria isolated from Prosopis cineraria. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2023, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, A.A.; Koksharova, O.A.; Lipasova, V.A.; Zaitseva, J.V.; Katkova-Zhukotskaya, O.A.; Eremina, S.; Mironov, A.S.; Chernin, L.S.; Khmel, I.A. Inhibitory and toxic effects of volatiles emitted by strains of Pseudomonas and Serratia on growth and survival of selected microorganisms, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Drosophila melanogaster. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 125704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, S.; Lee, K.-J.; Shukla, P.; Chae, J.-C. Dimethyl disulfide exerts antifungal activity against Sclerotinia minor by damaging its membrane and induces systemic resistance in host plants. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6547, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Türksoy, G.M.; Berka, M.; Wippel, K.; Koprivova, A.; Carron, R.A.; Rüger, L.; Černý, M.; Andersen, T.G.; Kopriva, S. Bacterial community-emitted volatiles regulate Arabidopsis growth and root architecture in a distinct manner of those from individual strains. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittiampon, N.; Kaewchada, A.; Jaree, A. Carbon dioxide absorption using ammonia solution in a microchannel. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2017, 63, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Guo, Y.; Niu, Z.; Lin, W. Mass transfer coefficients for CO2 absorption into aqueous ammonia solution using a packed column. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 10168–10175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, D.; Prasad, S.S.; Ghosh, S. Isolation, screening and application of a potent PGPR for enhancing growth of Chickpea as affected by nitrogen level. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2020, 26, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreshtha, K.; Prakash, A.; Pandey, P.K.; Pal, A.K.; Singh, J.; Tripathi, P.; Mitra, D.; Jaiswal, D.K.; Santos-Villalobos, S.L.; Tripathi, V. Isolation and characterization of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from cacti root under drought condition. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 8, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weise, T.; Kai, M.; Piechulla, B. Bacterial ammonia causes significant plant growth inhibition. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, C.; Xiao, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhu, L.; Ma, Z. Enhanced iron and selenium uptake in plants by volatile emissions of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (BF06). Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondi, M.; Eisa, M.; Bortoletto-Santos, R.; Drapanauskaite, D.; Reddington, T.; Williams, C.; Ribeiro, C.; Baltrusaitis, J. Recovering, stabilizing, and reusing nitrogen and carbon from nutrient-containing liquid waste as ammonium carbonate fertilizer. Agriculture 2023, 13, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-K.; Chen, R.-Y. Ammonium bicarbonate used as a nitrogen fertilizer in China. Fertil. Res. 1980, 1, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govoni Brondi, M.; Bortoletto-Santos, R.; Farias, J.G.; Farinas, C.S.; Ammar, M.; Ribeiro, C.; Williams, C.; Baltrusaitis, J. Mechanochemically synthesized nitrogen-efficient Mg- and Zn-ammonium carbonate fertilizers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 6182–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-G.; Lu, X.-Q.; Chen, J. Gasotransmitter ammonia accelerates seed germination, seedling growth, and thermotolerance acquirement in maize. Plant Signal. Behav. 2023, 18, 2163338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasketa, A.; González-Moro, M.B.; González-Murua, C.; Marino, D. Exploring ammonium tolerance in a large panel of Arabidopsis thaliana natural accessions. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 6023–6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Zabala, J.; González-Murua, C.; Marino, D. Mild ammonium stress increases chlorophyll content in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e991596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxmi, V.; Gupta, M.N.; Datta, S.K. Investigations on an induced green seed coat colour mutant of Trigonella foenum-graecum. L. Cytologia 1983, 48, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittberner, H.; Korte, A.; Mettler-Altmann, T.; Weber, A.P.M.; Monroe, G.; de Meaux, J. Natural variation in stomata size contributes to the local adaptation of water-use efficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 4052–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, S.; Min, W.K.; Seo, H.S. Arabidopsis COP1 guides stomatal response in guard cells through pH regulation. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.M.; Kang, B.R.; Han, S.H.; Anderson, A.J.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Cho, B.H.; Yang, K.Y.; Ryu, C.M.; Kim, Y.C. 2R,3R-butanediol, a bacterial volatile produced by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6, is involved in induction of systemic tolerance to drought in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2008, 21, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Shen, Z.-J. Stomatal clustering, a new marker for environmental perception and adaptation in terrestrial plants. Bot. Stud. 2010, 51, 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- Sugano, S.S.; Shimada, T.; Imai, Y.; Okawa, K.; Tamai, A.; Mori, M.; Hara-Nishimura, I. Stomagen positively regulates stomatal density in Arabidopsis. Nature 2010, 463, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment | Length of Guard Cell (µm) | Width of Guard Cell (µm) | Stomatal Density (n/mm2) | Closed Stomata (n/mm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEEL19 V− | 6.11 ± 0.18 b | 5.45 ± 0.34 a | 17.06 ± 0.81 a | 8.79 ± 0.60 b |

| NEEL19 V+ | 6.50 ± 0.27 a | 5.73 ± 0.12 a | 19.81 ± 0.28 a | 17.32 ± 0.00 a |

| 5 µL ddH2O | 5.68 ± 0.02 d | 4.87 ± 0.12 d | 18.63 ± 0.82 b | 9.32 ± 1.64 b |

| 1 µL NH4OH | 5.78 ± 0.04 c,d | 5.30 ± 0.06 b,c | 17.59 ± 0.23 b | 8.92 ± 1.59 b |

| 2 µL NH4OH | 5.72 ± 0.21 d | 5.05 ± 0.17 c,d | 18.77 ± 0.60 b | 9.97 ± 0.90 b |

| 3 µL NH4OH | 6.07 ± 0.23 b,c | 5.55 ± 0.29 a,b | 22.18 ± 0.45 a | 14.70 ± 0.22 a |

| 4 µL NH4OH | 6.53 ± 0.17 a | 5.75 ± 0.14 a | 21.13 ± 1.59 a | 14.70 ± 1.27 a |

| 5 µL NH4OH | 6.34 ± 0.03 a,b | 5.80 ± 0.19 a | 20.73 ± 1.38 a | 14.44 ± 2.02 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neelakandan, P.; Shen, F.-T.; Lin, S.-Y.; Lin, S.-H.; Young, C.-C. Influence of Pseudomonas sp. NEEL19 Expelled Volatile Compounds on Growth and Development of Crop Seedlings. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2754. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122754

Neelakandan P, Shen F-T, Lin S-Y, Lin S-H, Young C-C. Influence of Pseudomonas sp. NEEL19 Expelled Volatile Compounds on Growth and Development of Crop Seedlings. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2754. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122754

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeelakandan, Poovarasan, Fo-Ting Shen, Shih-Yao Lin, Shih-Han Lin, and Chiu-Chung Young. 2025. "Influence of Pseudomonas sp. NEEL19 Expelled Volatile Compounds on Growth and Development of Crop Seedlings" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2754. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122754

APA StyleNeelakandan, P., Shen, F.-T., Lin, S.-Y., Lin, S.-H., & Young, C.-C. (2025). Influence of Pseudomonas sp. NEEL19 Expelled Volatile Compounds on Growth and Development of Crop Seedlings. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2754. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122754