1. Introduction

Bacterial aggregation is a conserved adaptive trait that enables survival in diverse environments, with surface-attached forms (e.g., biofilms) and non-attached variants (e.g., pellicles, planktonic aggregates) representing distinct strategies for evading stressors [

1,

2]. For

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Staphylococcus aureus, planktonic aggregates drive antibiotic tolerance and immune evasion [

3], yet their role in

Acinetobacter baumannii—one of the most problematic multidrug-resistant (MDR) nosocomial pathogens [

4]—remains uncharacterized.

A. baumannii uses biofilms and pellicles for resistance [

5,

6,

7], with RND efflux pumps (e.g., AdeFGH, AdeABC) driving MDR phenotypes [

8,

9]. A variety of efflux pump families have been identified in

A. baumannii, among which the most clinically relevant is the Resistance Nodulation Division (RND) family [

10]. The RND family includes the following main efflux pump systems: (1) AdeABC is the first efflux pump system identified in the RND family and is widely present in clinical isolates of

A. baumannii. This system consists of AdeA (membrane fusion protein), AdeB (plasma membrane transporter), and AdeC (outer membrane channel protein). AdeABC expression is regulated by the AdeSR two-component system (TCS) [

11,

12]. AdeS is a membrane-bound histidine kinase that senses environmental signals (including antibiotics) and activates AdeR (a response regulatory protein) by phosphorylation, thereby promoting AdeABC expression [

13]. (2) AdeIJK is another important RND efflux pump system in

A. baumannii, which has a wide range of substrate specificity [

14]. This system is present in the core genome of all

A. baumannii strains and is thought to be the ancestral efflux pump of the genus. AdeIJK expression is regulated by AdeN, but its regulatory mechanism is different from that of AdeABC [

15]. (3) AdeFGH is a little-studied efflux pump system in the RND family, which endows

A. baumannii with multidrug resistance when overexpressed [

16]. Compared with other RND efflux pumps, the regulatory mechanism of AdeFGH is more complex, and overexpression of AdeFGH has the greatest negative impact on bacterial fitness. The AdeFGH efflux pump family is regulated by AdeL, a LysR-type transcriptional repressor (LTTR) located upstream of the adeFGH operon (

Figure S1). Prior work linked RND pumps to biofilm formation [

9], but their role in planktonic aggregates is unknown. Three critical gaps persist: (1) Does

A. baumannii form planktonic aggregates in liquid environments, given prior focus only on pellicles? (2) What genetic mechanisms govern aggregation—could RND genes like

adeG crosstalk with adhesion genes (

csu/

pil) or alter cell hydrophobicity? (3) Do aggregates enhance antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity, potentially via metabolic dormancy or serum shielding? Notably, most studies focus on MDR

A. baumannii, while non-MDR strains—still causing persistent infections in immunocompromised patients—remain understudied, with their adaptive strategies (e.g., aggregation) unaddressed [

17,

18].

Resolving these gaps is clinically urgent, as non-MDR A. baumannii infections are increasingly refractory to standard therapies. Here, we used 103 clinical isolates, adeG-deleted mutants, and multi-dimensional assays to test three hypotheses: Mechanistically, non-MDR A. baumannii (with RND deletions) form more aggregates than MDR strains; adeG regulates aggregation via csu/pil and hydrophobicity. Functionally, aggregates enhance antibiotic tolerance, serum resistance, and in vivo pathogenicity. This work aims to fill key gaps in A. baumannii survival strategies and identify novel infection targets.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria

Acinetobacter baumannii strains used in this study are clinical isolates (

Table S1) recovered from patient specimens, including wound exudates, sputum, blood, and other clinical samples, and were archived by our research group during prior investigations. All strains were preserved at −80 °C in Nutrient Broth (NB; Solarbio, Beijing, China) supplemented with 15% (vol/vol) glycerol. For experimental preparation, strains were streaked onto NB agar plates (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h to isolate single colonies. Isolated single colonies were then inoculated into fresh NB and cultured to mid-logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD

600] = 0.5–0.6) under the same temperature conditions.

2.2. Amplification of Efflux Pump Genes

The presence of RND family efflux pump genes in

A. baumannii clinical isolates was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using bacterial suspensions as direct templates (without prior DNA extraction). PCRs were prepared in 25 μL volumes containing 12.5 μL of 2× Taq Plus Master Mix II (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China), 1 μL of each forward and reverse primer (10 μM; sequences listed in

Table S2), and 2 μL of bacterial suspension. Thermocycling was performed with the following parameters: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 56 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Amplicons were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels (containing 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide) and visualized under ultraviolet transillumination.

2.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and MIC Determination

Antibiotic susceptibility was assessed per the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) 2023 guidelines [

19] using the standard broth microdilution method to determine minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of target bacteria. Briefly, four clinically relevant antibiotics—ceftazidime, levofloxacin, polymyxin B, and meropenem (purchased from Yuanye Bio, Shanghai, China; Macklin, Shanghai, China)—were serially 2-fold diluted in NB in 96-well microtiter plates. An equal volume (50 μL) of bacterial suspension was added to each well, resulting in a final bacterial concentration of ~1 × 10

6 CFU/mL per well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C under ambient air for 16 h, and the MIC was defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration at which no macroscopic bacterial growth was observed.

2.4. Construction of adeG Gene Deletion Mutants

adeG deletion mutants were constructed using the RecAb-mediated homologous recombination system. Briefly, a recombinant fragment containing the kanamycin resistance cassette (kan) flanked by ~500 bp upstream and downstream homologous arms of

adeG was synthesized and cloned into the pAT04 vector (Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA). The resulting plasmid was electroporated into

A. baumannii strains YZUMab17 and ZJab1 using a Gene Pulser Xcell system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) set to 2.5 kV, 25 μF, and 200 Ω. Transformants (YZUMab17-pAT04 and ZJab1-pAT04) were selected on LB agar containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and 100 μg/mL ampicillin. For homologous recombination, the kanamycin resistance fragment with homologous arms was electroporated into YZUMab17-pAT04 and ZJab1-pAT04, and recombinant strains (YZUMab17Δ

adeG::kan(pAT04) and ZJab1Δ

adeG::kan(pAT04)) were screened by colony PCR using primers

AdeG-F and

AdeG-R (

Table S3). The pAT04 plasmid was cured by serial passage in LB broth without antibiotics, confirmed by loss of ampicillin resistance. Subsequently, the pAT03 plasmid (Addgene), which encodes the FLP recombinase, was electroporated into YZUMab17Δ

adeG::kan and ZJab1Δ

adeG::kan to excise the kanamycin resistance cassette. Positive clones lacking the kan cassette were identified using colony PCR with primers

AdeG-F and

AdeG-R, and pAT03 was eliminated by passage at 42 °C to obtain the final mutants YZUMab17Δ

adeG and ZJab1Δ

adeG. All primer sequences are listed in

Table S3.

2.5. Macroscopic Observation of Bacterial Aggregates

A single A. baumannii colony was inoculated into NB (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and cultured at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm) for 16 h. The suspension was adjusted to OD600 = 0.6 with fresh NB, then diluted 1:1000 in NB to standardize inocula. Diluted cultures were dispensed into sterile containers: 200 μL in 96-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA), 4 mL in glass tubes (15 × 100 mm), and 10 mL in 10 cm Petri dishes (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). All were incubated statically at 37 °C for 24 h to promote aggregation. Macroscopic images were captured with an iPhone 14 Pro (Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA) under controlled conditions: uniform white background, 6500 K LED illumination (30 cm above samples), and tripod-fixed phone at container-specific distances (15 cm for plates, 20 cm for tubes, 25 cm for dishes) to ensure consistent imaging.

2.6. Observation of Aggregates by Gram Staining

Gram staining of planktonic and aggregated bacteria was performed using a commercial kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Bacterial samples were heat-fixed on slides (3× passes through a Bunsen burner flame at 45°). Staining steps: crystal violet for 1 min (rinsed with distilled water); iodine solution for 1 min (rinsed); 95% ethanol decolorization until eluate cleared (~30 s, rinsed immediately); safranin counterstaining for 1 min (rinsed, air-dried at room temperature). Samples were examined under a light microscope (Olympus CX43, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at 1000× oil immersion, with images captured via an Olympus DP27 camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) under consistent illumination.

2.7. Observation of Aggregates by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

For SEM analysis, planktonic cells of the wild-type strain and aggregated cells of the mutant strain were inoculated onto sterile glass coverslips (12 mm diameter) placed in 24-well culture plates. Samples were fixed overnight at 4 °C in 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). After fixation, cells were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%; 15 min per step) and dried using a critical point dryer (Leica EM CPD300, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) with liquid CO2 as the transition fluid. Dried samples were mounted on aluminum stubs with carbon tape and sputter-coated with a 10 nm layer of gold–palladium using a sputter coater (Quorum Q150T ES, Quorum Technologies, East Sussex, UK). Specimens were examined using a scanning electron microscope (FEI Quanta 200, FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA) operated at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV, and images were captured at 1000× to 10,000× magnification to analyze aggregate morphology and structure.

2.8. Quantitative Analysis of Bacterial Aggregation

Exponential-phase bacterial cultures were diluted and inoculated into two sets of culture tubes containing fresh NB, with three biological replicates per set. The final bacterial density in each tube was adjusted to approximately 1 × 106 colony-forming units (CFUs)/mL. All tubes were incubated at 37 °C to induce aggregate formation. For the first set of tubes, the planktonic bacterial suspension was carefully aspirated using a pipette, with the tip positioned to avoid contact with visible aggregates and biofilms; the remaining aggregates were retained in the tubes. The aspirated suspension was vortexed thoroughly (30 s at maximum speed), and its optical density was measured at 600 nm (OD0). For the second set, the entire culture (including planktonic cells and aggregates, while avoiding biofilm contact) was transferred to a sterile microcentrifuge tube, vortexed thoroughly to disperse aggregates, and its optical density was measured at 600 nm (OD1). The ratio of aggregated to non-aggregated bacteria (Agg./Non-agg.) was calculated as follows: Agg./Non-agg. = (OD1 − OD0)/OD0. All measurements were performed in triplicate, with mean values ± standard deviation (SD) reported.

2.9. Growth Curve Analysis

Bacterial cultures were adjusted to an OD

600 of 0.5, then diluted 1:100 in fresh NB. Diluted cultures (200 μL/well) were dispensed into a 96-well microtiter plate (Corning) and incubated at 37 °C with continuous shaking (200 rpm) in a microplate reader (BioTek Epoch 2, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). OD

600 measurements were recorded every hour for 24 h to monitor growth kinetics. Experiments were performed in three independent biological replicates, each with three technical replicates. Growth curves were constructed by plotting time (hours) on the

x-axis and mean OD

600 values (± standard deviation) on the

y-axis using OriginPro 2024 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Curves were fitted with a logistic regression model, and growth phases (lag, exponential, and stationary phases) were determined by the tangent method, as described by Zwietering et al. [

20]. Briefly, the inflection point of the exponential phase was identified, and tangents to the growth curve at this point were used to calculate the following: (i) lag phase duration (time from inoculation to intersection of the tangent with the initial OD

600); (ii) maximum growth rate (slope of the tangent during exponential phase); and (iii) stationary phase OD

600 (plateau value of the fitted curve).

2.10. Ethidium Bromide Efflux Assay

The ethidium bromide (EB) efflux assay was performed as previously described [

21] with minor modifications. Bacterial cultures were inoculated 1:1000 into NB and grown at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm) for 16 h. Cultures were adjusted to an OD

600 of 0.6, and 1.2 mL aliquots were pre-chilled at 4 °C for 1 h. Ethidium bromide (EB; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) working solution (50 μM) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) were also pre-chilled at 4 °C. EB was added to chilled bacterial suspensions to a final concentration of 5 μM, followed by incubation at 4 °C for 5 min to allow passive uptake. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (5000×

g, 5 min, 4 °C), supernatant was aspirated, and pellets were resuspended in an equal volume of pre-chilled PBS. A 200 μL aliquot was transferred to a black 96-well microplate (Corning) for immediate fluorescence measurement (excitation 350 nm, emission 590 nm) using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy H1, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), designated as T

0. The remaining suspension was incubated at 20 °C to initiate efflux, with 200 μL aliquots collected at 5, 10, 15, and 20 min. At each time point, cells were centrifuged (5000×

g, 5 min, 20 °C), the supernatant was discarded, and pellets were resuspended in PBS before fluorescence measurement. The efflux coefficient was calculated as follows: Efflux Coefficient = (F

0 − F

t)/F

0, where F

0 is fluorescence at T

0, and F

t is fluorescence at each time point.

2.11. Surface-Associated Motility Assay

The surface-associated motility was assessed using semi-solid agar plates, as previously described [

22], with minor modifications. Semi-solid LB agar plates (0.5% agar,

w/

v) were prepared by pouring 15–20 mL of molten agar onto level surfaces to ensure uniform thickness (≈3 mm). Plates were allowed to solidify at room temperature for 1 h before use. A single colony from a freshly streaked LB agar plate was inoculated into NB and cultured overnight at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm). The overnight culture was adjusted to an OD

600 of 0.6 using fresh LB broth. A 5 μL aliquot of the normalized bacterial suspension was gently spotted onto each semi-solid agar plate, taking care not to pierce the agar surface. Plates were left undisturbed for 10–15 min to allow for complete absorption of the inoculum. Plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 16–24 h. Motility was quantified by measuring the diameter of the spreading zone from the edge of the inoculation point to the outermost margin of bacterial growth using digital calipers (accuracy ± 0.01 mm).

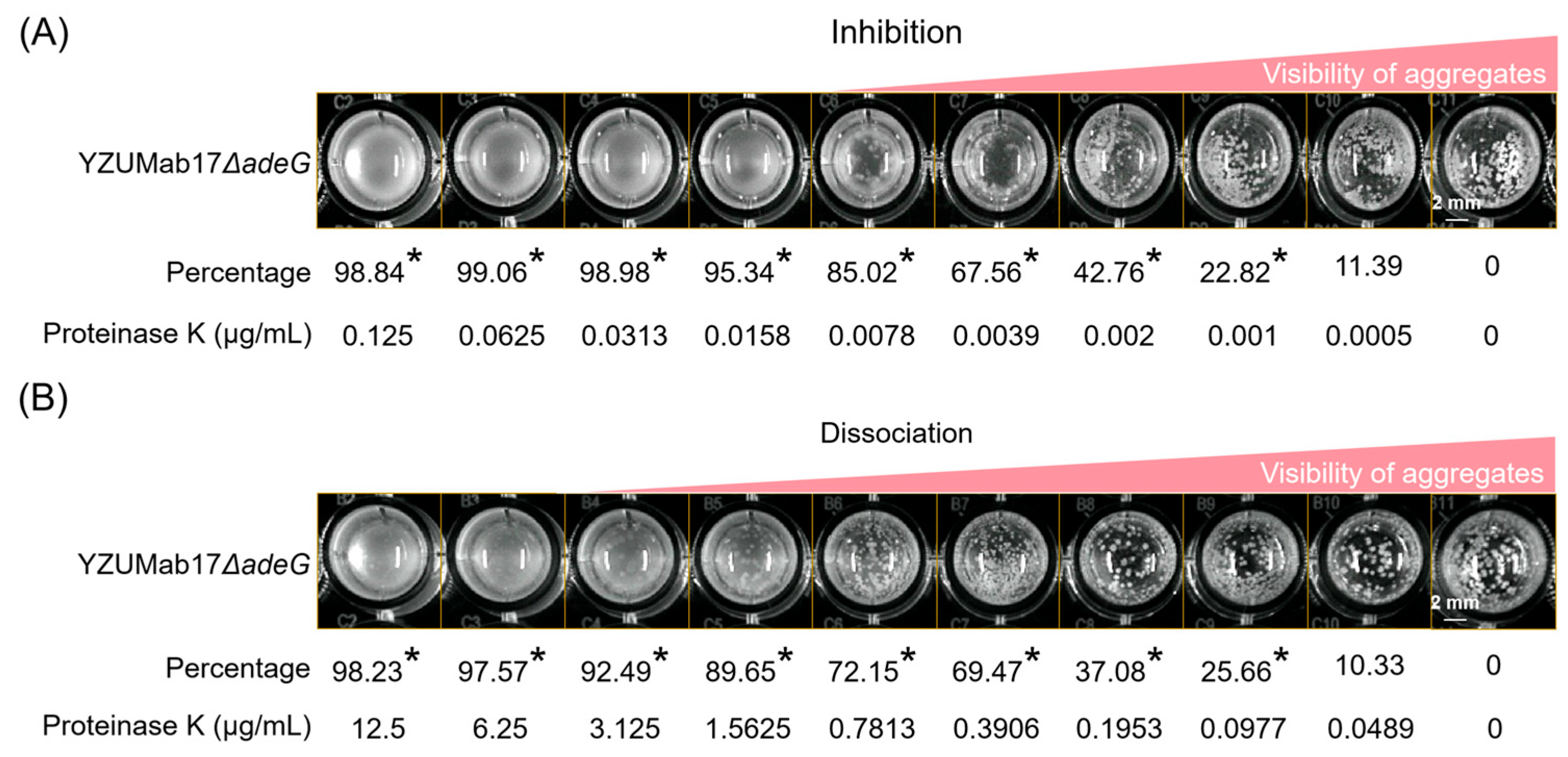

2.12. Aggregation Inhibition and Disaggregation Assays

The effects of Proteinase K, sodium periodate (NaIO

4), and DNase I on bacterial aggregation were evaluated using established protocols [

23] with modifications. Test reagents included Proteinase K (Solarbio, Beijing, China), sodium periodate (NaIO

4; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

- (1)

Aggregation Inhibition Assay

Exponential-phase bacterial cultures (OD600 = 0.5) were diluted 1:1000 in fresh NB and mixed with test reagents at final concentrations of 10–100 μg/mL (Proteinase K), 1–10 mM (NaIO4), or 10–50 U/mL (DNase I). Aliquots (200 μL) of each mixture were dispensed into 96-well plates (Corning) and incubated statically at 37 °C for 24 h.

- (2)

Aggregation Disaggregation Assay

Bacterial aggregates were pre-formed by incubating 1:1000-diluted cultures (OD600 = 0.5) in 96-well plates at 37 °C for 24 h. Test reagents were then added to wells at the same concentrations as above, followed by static incubation at 37 °C for 2 h to assess dispersion of pre-formed aggregates.

Images from both assays were acquired using an automated chemiluminescence imaging system (Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) under standardized illumination conditions. Aggregate inhibition and disaggregation rates were calculated by comparing quantitative parameters of treatment groups to untreated controls, using the aggregation quantification method described above.

2.13. Antibiotic Survival Assay

Exponential-phase bacterial cultures (OD600 = 0.5) were diluted 1:100 in fresh NB and grown statically at 37 °C for 24 h to form aggregates. Cultures were divided into three groups: (i) 64× MIC antibiotic treatment, (ii) ultrasound pretreatment followed by antibiotic exposure, and (iii) antibiotic-free control. After 12 h of co-incubation at 37 °C, cultures were centrifuged (5000× g, 5 min), supernatants discarded, and pellets resuspended in sterile 0.9% NaCl. Aggregates were disrupted by sonication (30 s on/30 s off, 3 cycles at 20% amplitude) using a probe sonicator (QSonica Q500, Qsonica, LLC, Newtown, CT, USA), and viable counts were determined with serial dilution and plating on LB agar, incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to enumerate CFU. For a time-course analysis, 1:1000-diluted cultures (OD600 = 0.5) were incubated with shaking (200 rpm) at 37 °C for 6, 12, or 24 h. At each time point, cultures were adjusted to OD600 = 0.5 and split into antibiotic-treated or untreated control groups. Treatment groups received antibiotics at strain-specific concentrations: ceftazidime, levofloxacin, and meropenem at 8× MIC (co-incubated for 12 h); polymyxin and gentamicin at 4× MIC (co-incubated for 4 h). Following incubation, cultures were centrifuged (5000× g, 5 min), pellets resuspended in sterile 0.9% NaCl, and CFU enumerated as described above. All experiments were performed in triplicate with three biological replicates, and results are reported as mean CFU/mL ± standard deviation.

2.14. ATP Content Measurement

Intracellular ATP levels were quantified using an Enhanced ATP Assay Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), following the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modifications. Bacteria were cultured under two conditions: (i) static incubation (37 °C, 24 h) and (ii) shaking incubation (37 °C, 200 rpm, 24 h). After cultivation, bacterial pellets (10 mg wet weight per strain) were harvested by centrifugation (5000× g, 5 min, 4 °C).

For cell lysis, 200 μL of ice-cold lysis buffer (pre-chilled and maintained on ice) was added to each pellet, followed by vortexing for 30 s and incubation on ice for 5 min. Lysates were centrifuged (12,000× g, 5 min, 4 °C), and supernatants were collected and kept on ice until analysis. A standard curve was generated using the kit-provided ATP standard: the standard was subjected to one freeze–thaw cycle, then serially diluted in lysis buffer to final concentrations of 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, and 10 μM. The ATP detection reagent was diluted 1:4 with the kit-supplied dilution buffer to prepare a working solution, which was stored on ice for up to 1 h (short-term use). For luminescence detection, 100 μL of the ATP detection working solution was added to each well of a white 96-well plate (Corning) and equilibrated at room temperature for 3–5 min. Twenty microliters of the sample supernatant or ATP standard was then added to each well, mixed immediately by pipetting (3× up and down), and luminescence (relative light units, RLU) was measured within 2 s using a multimode microplate reader (Tecan Spark, Männedorf, Switzerland) with a luminescence detection module (gain setting: 100). Intracellular ATP concentrations were calculated by interpolating sample RLU values against the ATP standard curve.

2.15. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

Exponential-phase bacterial cultures (OD600 = 0.5) were diluted 1:1000 in fresh NB, and 10 mL aliquots were transferred to 90 mm sterile polystyrene culture dishes (Corning). Dishes were incubated statically at 37 °C for 24 h to induce aggregation. Surface-associated bacterial aggregates were gently collected using a sterile Pasteur pipette, transferred to 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes, and rinsed three times with 1 mL of fresh nutrient broth to remove planktonic cells. All samples were flash-frozen at −80 °C for 24 h, lyophilized using a freeze-dryer (Labconco FreeZone 2.5, Labconco Corporation, Fort Scott, KS, USA) for 48 h, and stored at 4 °C until analysis. FTIR spectra were acquired using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Varian 670-IR, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a diamond attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessory. Lyophilized samples (≈5 mg) were pressed onto the ATR crystal, and spectra were recorded over the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1 with 32 scans and a resolution of 4 cm−1. Background spectra of the clean ATR crystal were collected before each sample measurement and subtracted from sample spectra.

2.16. Cell Surface Hydrophobicity (CSH)

Bacterial surface hydrophobicity was determined using the microbial adhesion to hydrocarbons (MATH) assay, as previously described [

24], with minor modifications. Overnight bacterial cultures were harvested by centrifugation (5000×

g, 5 min, 4 °C), resuspended in sterile 0.9% NaCl, and adjusted to an OD

600 of 0.5 (designated as OD

0). A 2 mL aliquot of the standardized bacterial suspension was mixed with 1 mL of xylene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a 15 mL glass centrifuge tube. The mixture was vortexed vigorously for 30 s to ensure emulsification, then incubated undisturbed in a fume hood for 15 min at room temperature to allow for phase separation. After separation, the aqueous phase (lower layer) was carefully aspirated, and its optical density was measured at 600 nm (designated as OD

1) using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Synergy 2, BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Cell surface hydrophobicity was calculated as follows: CSH = (1 − OD

1/OD

0) × 100%.

2.17. Auto-Aggregation Assay

Bacterial auto-aggregation was evaluated as previously described [

25], with minor modifications. Overnight bacterial cultures were harvested by centrifugation (6000×

g, 10 min, 4 °C), supernatants discarded, and pellets resuspended in sterile 0.9% NaCl. The bacterial suspension was adjusted to an OD

600 of 0.5 (designated as OD

0) using sterile 0.9% NaCl. A 2 mL aliquot of the standardized suspension was transferred to a sterile 5 mL glass centrifuge tube and incubated statically at room temperature to allow for auto-aggregation. At 15, 30, and 60 min post-incubation, 200 μL of the upper-layer suspension (avoiding settled aggregates) was carefully aspirated using a pipette tip positioned 1 cm below the liquid surface. The OD

600 of the aspirated suspension was measured (designated as OD

t, where t = 15, 30, or 60 min) using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Synergy 2). The auto-aggregation percentage was calculated as follows: Auto-aggregation (%) = [1 − (OD

t/OD

0)] × 100%.

2.18. Polystyrene Surface Adhesion Assay

Bacterial adhesion to polystyrene surfaces was assessed as previously described [

26], with minor modifications. Exponential-phase bacterial cultures (OD

600 = 0.5) were diluted 1:100 in fresh NB, and 200 μL aliquots were dispensed into sterile 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates (Corning). Plates were incubated statically at 37 °C to monitor adhesion kinetics over time. At 15, 30, 45, and 60 min post-inoculation, the total bacterial growth in each well was quantified by measuring OD

600 using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Synergy 2). For adhesion quantification, culture supernatants were aspirated, and wells were rinsed three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to remove non-adherent cells. Adherent bacteria were stained with 200 μL of 0.1% (

w/

v) crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature for 15 min. Any excess stain was removed by washing three times with PBS, and plates were air-dried for 10 min. Bound crystal violet was solubilized with 200 μL of absolute ethanol, and the absorbance at 600 nm (OD

600) was measured to quantify adherent cells.

2.19. Cell Adhesion and Invasion Assays

Bacterial adhesion and invasion into A549 lung epithelial cells were assessed as previously described [

27], with minor modifications. First, A549 cells were seeded in 24-well plates (Corning) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37 °C in a 5% CO

2 incubator until reaching 70% confluence. Overnight bacterial cultures were centrifuged (5000×

g, 5 min, 4 °C) and adjusted to an OD

600 of 0.5. For adhesion assays, bacteria were resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), while for invasion assays, they were resuspended in antibiotic-free RPMI 1640 medium (≈5 × 10

7 CFU/mL, verified by plate counting).

For the adhesion assay, 1 mL of the PBS-resuspended bacterial suspension was added to wells containing confluent A549 cells and incubated at 37 °C/5% CO2 for 2 h; after incubation, non-adherent bacteria were removed by three PBS washes, and adherent bacteria were detached with 500 μL of 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) (37 °C, 10 min, 50 rpm shaking), followed by 10-fold serial dilution of the suspension in sterile 0.9% NaCl, plating of 100 μL aliquots on LB agar (37 °C, 24 h), and counting of total adherent CFU.

For the invasion assay, 1 mL of the antibiotic-free RPMI 1640-resuspended bacterial suspension was added to A549-containing wells and incubated at 37 °C/5% CO2 for 2 h; non-adherent bacteria were then removed by three PBS washes, extracellular bacteria (including surface-adherent ones) were killed with 500 μL of RPMI 1640 medium containing 500 μg/mL gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich) (37 °C, 30 min), and residual gentamicin was removed by two additional PBS washes. Infected A549 cells were lysed with 500 μL of 0.25% trypsin-EDTA supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100 (37 °C, 10 min, 50 rpm shaking), and the lysate was serially diluted 10-fold in sterile 0.9% NaCl, with 100 μL aliquots plated on LB agar (37 °C, 24 h) to count intracellular CFUs.

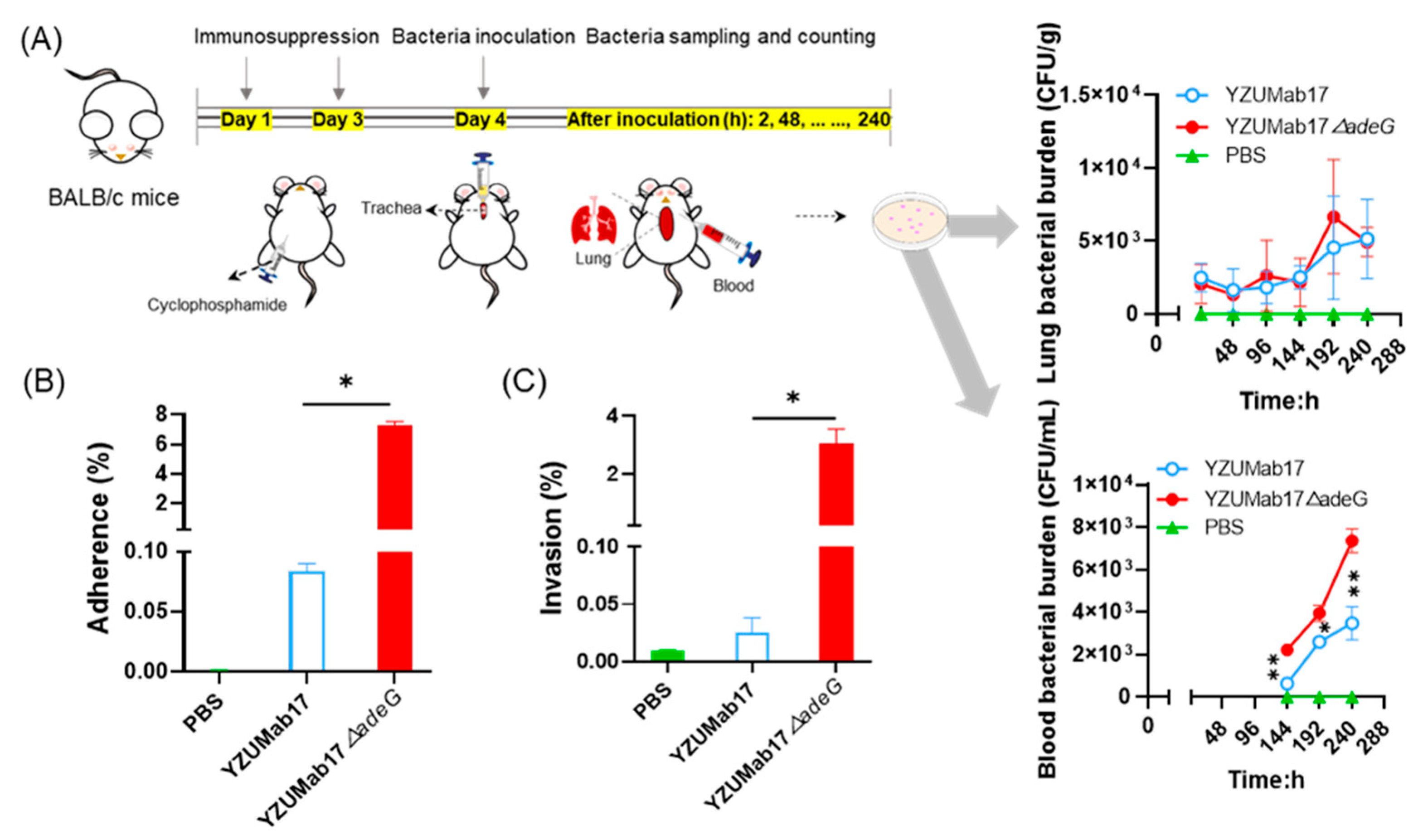

2.20. Mouse Infection Model

The mouse infection model was established as previously described [

28] with minor modifications, specifically designed to mimic clinical scenarios of

A. baumannii infection in immunocompromised populations (e.g., ICU patients, neutropenic individuals)—a key group at high risk of recalcitrant infections. Six- to eight-week-old immunocompromised BALB/c mice (rendered immunosuppressed via cyclophosphamide pretreatment to deplete innate and adaptive immune cells;

n = 5 per time point) were maintained under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions with ad libitum access to food and water. Bacterial suspensions were prepared by adjusting overnight cultures of

A. baumannii (parental strain YZUMab17 and its

adeG-deleted mutant YZUMab17Δ

adeG) to 5 × 10

6 CFU/mL in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in oxygen, then infected via intratracheal inoculation with 50 μL of the bacterial suspension (2.5 × 10

5 CFU per mouse)—a route that recapitulates respiratory tract colonization, the primary portal of entry for

A. baumannii in clinical settings (e.g., ventilator-associated pneumonia). At 2 h, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days post-infection, mice were euthanized by CO

2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation (per AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals). Blood samples (≈100 μL) were collected via cardiac puncture into EDTA-coated tubes to assess bacteremia, a severe complication of

A. baumannii infection in immunocompromised patients. Lungs were aseptically harvested, weighed, and homogenized in 1 mL of sterile PBS using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) to quantify pulmonary bacterial burden-reflecting the organism’s ability to colonize and persist in a primary target organ. All samples were subjected to ultrasonic dispersion of aggregates prior to bacterial counting. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of Yangzhou University (Permit No. 202502033) and conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 2011). Results are reported as mean bacterial burden ± standard deviation.

2.21. Serum Bactericidal Assay

The serum bactericidal assay was performed as previously described [

29], with minor modifications: mid-log phase bacterial cultures (OD

600 = 0.5) were harvested by centrifugation (5000×

g, 5 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to a concentration of ≈5 × 10

5 CFU/mL; then, bacterial suspensions were diluted 1:100 in fresh NB supplemented with healthy human serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at final concentrations of 0%, 10%, 25%, 50%, and 75% (

v/

v). Aliquots (200 μL) of each mixture were dispensed into sterile 96-well plates (Corning) and incubated statically at 37 °C for 24 h; after incubation, 100 μL of bacterial suspension from each well was serially diluted 10-fold in sterile PBS, 10 μL aliquots of each dilution were plated on LB agar, plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h, and colony-forming units (CFUs) were enumerated to quantify viable bacteria. Bactericidal activity was calculated using the formula: Serum bactericidal rate (%) = [1 − (CFU in serum-treated wells/CFU in serum-free control wells)] × 100%.

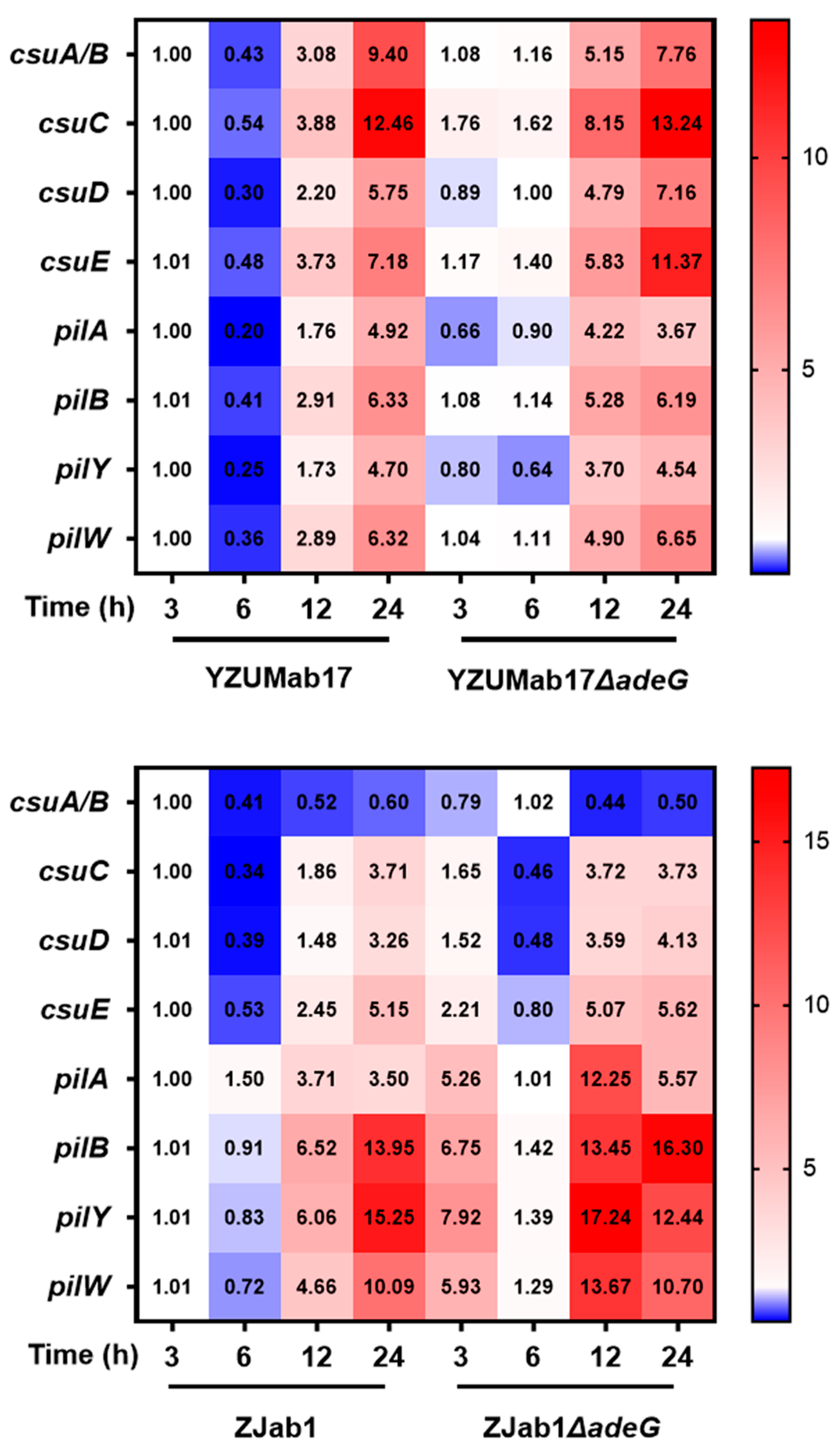

2.22. Gene Expression Assay

Exponential-phase bacterial cultures (OD

600 = 0.5) were sub-cultured at a 1:1000 dilution in fresh NB and incubated with shaking (200 rpm) at 37 °C; at 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post-subculture, 1 mL of bacterial culture was harvested by centrifugation (8000×

g, 5 min, 4 °C), and cell pellets were immediately frozen at −80 °C until RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Solarbio, Beijing, China) per the manufacturer’s protocol, with an additional DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) treatment (37 °C for 30 min) to remove genomic DNA, and RNA concentration/purity was determined via a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by measuring A

260/A

280 (target: 1.8–2.0) and A

260/A

230 (target: 2.0–2.2). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) with random hexamer primers (per manufacturer’s instructions), and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a SYBR Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China); the 20 μL reaction mixture contained 10 μL of SYBR Green Premix, 0.4 μL of each 10 μM gene-specific primer (listed in

Table S4, designed via Primer-BLAST [NCBI] (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/ (accessed on 15 March 2024)) and validated for 90–110% efficiency), 2 μL of 50 ng/μL cDNA template, and 7.2 μL of nuclease-free water, with thermocycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s, and a melting-curve analysis (65 °C to 95 °C with 0.5 °C increments) to verify amplicon specificity. The

rpoB gene served as the housekeeping reference, relative gene expression was calculated via the 2

−ΔΔCt method, all reactions were performed in triplicate with three biological replicates, and results are reported as mean fold change ± standard deviation relative to the 3 h time point.

2.23. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed with three independent biological replicates, each analyzed in technical triplicate. Statistical analysis of significant differences was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Pearson correlation matrices were visualized using the ggplot2 package (Version 3.3.3) within the RStudio (Version 1.4.1106) environment (RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

4. Discussion

Bacterial non-attached aggregates represent a conserved adaptive strategy distinct from biofilms and pellicles, driving antibiotic tolerance and persistent infections in pathogens such as

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Staphylococcus aureus [

3,

31]. For

A. baumannii—a leading multidrug-resistant (MDR) nosocomial pathogen—three critical knowledge gaps have persisted: whether planktonic aggregates form in liquid environments, what genetic mechanisms regulate their assembly, and how they impact antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity. Leveraging 103 clinical isolates,

adeG-deleted mutants, and multi-dimensional assays, this study addresses these gaps, demonstrating that

A. baumannii forms planktonic aggregates in backgrounds with

adeG-related RND efflux system defects, and that these aggregates boost bacterial adaptation and virulence. These findings advance our understanding of

A. baumannii’s survival strategies and identify novel therapeutic targets for combating recalcitrant infections.

A foundational observation of this study is the strain-specific prevalence of planktonic aggregates in

A. baumannii clinical isolates, with a striking bias toward non-MDR strains: 13.79% of non-MDR strains formed macroscopic aggregates visible to the naked eye, compared to only 1.35% of MDR strains. This distribution closely mirrors the pattern of RND efflux system gene deletions: 93.1% of non-MDR strains harbored deletions in RND operons (

adeSR-

adeABC,

adeL-

adeFGH, or

adeN-

adeIJK), whereas just 17.57% of MDR strains did so. This correlation initially suggested a link between RND efflux dysfunction and aggregate formation—consistent with the well-established role of intact RND systems in mediating MDR phenotypes in

A. baumannii [

8,

9]. However, our data refine this relationship by revealing that residual RND efflux activity, not mere gene deletions, is the key modulator. For example, clinically isolated strains, HFab23 (non-aggregating) and HFab43 (aggregating), shared identical Δ

adeC genotypes, but HFab23 retained higher residual efflux activity (evidenced by lower ethidium bromide [EtBr] retention). This finding extends beyond the canonical role of RND pumps in antibiotic extrusion [

32], demonstrating that these systems regulate

A. baumannii physiology, including membrane homeostasis and intercellular adhesion, in ways that directly impact aggregate assembly. The clinical relevance of this phenotype is underscored by its presence across diverse specimens: aggregate-forming strains were isolated from cerebrospinal fluid (HFab24, a sterile site), sputum (HFab23/HFab39/HFab43/HFab104), and urine (HFab55). This confirms that planktonic aggregates are not a laboratory artifact but a real-world trait, enabling

A. baumannii to persist in liquid-phase niches (e.g., bloodstream, respiratory tract) where surface-attached biofilms are less adaptive [

3].

The AdeFGH RND efflux pump, whose functional properties remain incompletely characterized, differs from the canonical AdeABC system, in that its core gene,

adeG, encodes a LysR-type transcription factor-regulated transmembrane channel protein, with its overexpression conferring enhanced resistance to antibiotics like tigecycline. Beyond drug efflux, AdeFGH also participates in bacterial aggregation: prior studies have shown it can modulate quorum-sensing molecule synthesis/transport to indirectly regulate biofilm formation and co-expression of

adeG, and the quorum-sensing gene

abaI can promote exopolymer production and bacterial clustering [

33,

34]. Although planktonic aggregates were formed in strain YZUMab17 following

adeG knockout, this aggregation phenotype was not eliminated in the

adeG-complemented strain YZUMab17Δ

adeG. Furthermore, no planktonic aggregation was observed in YZUMab17 when the entire

adeFGH operon was deleted. Meanwhile, ZJab1, a strain with a distinct genetic background, also failed to form planktonic aggregates after

adeG ablation. Based on these findings, we speculate that the

adeG gene does not directly regulate the formation of planktonic aggregates in

A. baumannii. The planktonic aggregation phenotype induced by

adeG knockout is strain-specific, and it is most likely attributable to the individual effects of polarity, secondary mutations, or background strain defects caused by the gene-editing procedure.

It was observed that the drug efflux activity of strain YZUMab17 was significantly reduced following

adeG knockout, which is consistent with the phenomenon observed in clinical strains—specifically, clinical strains exhibiting the planktonic aggregation phenotype generally harbor deletions in RND efflux system genes or show decreased efflux activity. Nevertheless, the effect of

adeG on RND efflux system function is strain-specific. In contrast to YZUMab17, ZJab1 displayed a tendency toward increased drug efflux activity after

adeG ablation (albeit with no statistically significant difference), accompanied by upregulated expression of the

adeB gene; additionally, the transcriptional pattern of

adeJ in ZJab1 was completely opposite to that in YZUMab17. Given the marked genetic background differences between YZUMab17 and ZJab1, the opposite transcriptional trends of

adeJ (upregulated in YZUMab17Δ

adeG; downregulated in ZJab1Δ

adeG) reflect genotype-specific regulatory differences rather than a direct modulation by

adeG deletion. Moreover,

adeG deletion remodeled growth kinetics to support aggregate assembly—YZUMab17Δ

adeG displayed a prolonged lag phase and reduced maximum growth rate (likely due to the metabolic cost of adhesive structure synthesis [

35]), with aggregate initiation at 6 h post-inoculation (coinciding with logarithmic growth), a pattern distinct from nutrient-limited pellicle formation [

5,

6]. Collectively, these findings position

adeG as an aggregation initiator that acts via cumulative RND efflux impairment, rather than direct gene regulation, reinforcing that aggregate-mediated traits are the key clinical and mechanistic focus of this study.

At the biophysical level, successful formation of planktonian aggregates depends on the coordinated regulation of bacterial motility, surface hydrophobicity, and self-aggregation ability, and changes in these traits are associated with the altered function of the RND efflux system: The relative movement velocity (RMV) of the YZUMab17Δ

adeG strain continued to increase after 6 h and reached the peak at 12 h, which was synchronized with the aggregate expansion process. Its “interior rough + periphery smooth” colony morphology cannot be attributed to hydrophobicity alone, and interior roughness may also be influenced by factors such as EPS secretion and local growth rate. However, combined with the high hydrophobicity data verified by MATH experiments (

Figure 9C) [

22,

24], it can be comprehensively judged that the strain has significantly increased hydrophobicity. In addition, the self-aggregation ability of this strain was enhanced, which further ensured the stability of bacterial adhesion. Pearson correlation analysis showed that the aggregation formation was significantly positively correlated with the above three traits, which revealed that the core of aggregate assembly was the synergistic effect of multiple biophysical traits, rather than the direct regulation of a single gene. The genetic background associated with

adeG only provides the conditions for the coordinated expression of these phenotypes, with the ultimate functional outcome being the efficient formation of planktonic aggregates.

A central finding is that planktonic aggregates enhance antibiotic tolerance independently of

adeG deletion. While

adeG deletion induced strain-specific MIC shifts, YZUMab17Δ

adeG exhibited enhanced survival under antibiotic stress despite these reduced MICs—a discrepancy explained by aggregation. Survival assays revealed a gradient: aggregated YZUMab17Δ

adeG > disaggregated YZUMab17Δ

adeG > parental YZUMab17. Non-aggregated YZUMab17Δ

adeG (dynamic culture) showed no survival advantage, ruling out

adeG deletion as a tolerance driver. ATP quantification uncovered the mechanism: aggregated YZUMab17Δ

adeG had significantly lower ATP levels than disaggregated cells and parental YZUMab17, indicating “metabolic dormancy” [

28]. Slow-growing, low-ATP cells are less susceptible to antibiotics targeting active processes (e.g., meropenem for cell wall synthesis, levofloxacin for DNA replication), a conserved tolerance mechanism extended here to

A. baumannii [

36].

Planktonic aggregates also boost

A. baumannii’s ability to evade host immunity and cause persistent infections. Serum resistance assays showed that YZUMab17Δ

adeG maintained stable proliferation across serum concentrations (1/16 U-1/512 U), while parental YZUMab17 exhibited concentration-dependent growth decline (bacteriostatic rate > 50% at 1/64 U serum). This resistance is mediated by dense, serum-induced flocculent aggregates that shield bacteria from complement proteins and antimicrobial peptides [

37], analogous to biofilm-mediated immune evasion [

7] but adapted for liquid environments. In a cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mouse model (mimicking ICU patients), YZUMab17Δ

adeG exhibited significantly persistent bacteremia. In vitro, YZUMab17Δ

adeG showed an ~80-fold higher adhesion rate and ~100-fold higher invasion rate to A549 lung epithelial cells, attributed to aggregate-associated pili [

38]. These data position aggregates as critical virulence determinants.

Temporal transcriptional analysis revealed robust

csu operon upregulation (critical for chaperone–usher pilus assembly) as a key driver of aggregation: YZUMab17Δ

adeG exhibited explosive

csu activation, aligning with aggregate initiation at 6 h. In contrast, non-aggregating ZJab1Δ

adeG lacked

csu upregulation, and isolated

pil activation was insufficient. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and enzyme assays confirmed proteins as the core matrix component, while polysaccharides/fatty acids were excluded due to low abundance [

39]. Proteinase K disrupted aggregates in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas sodium periodate (polysaccharide degrader) and DNase I (nucleic acid degrader) had no effect. This confirms that proteins—likely

csu-mediated pili—are essential for aggregate stability.

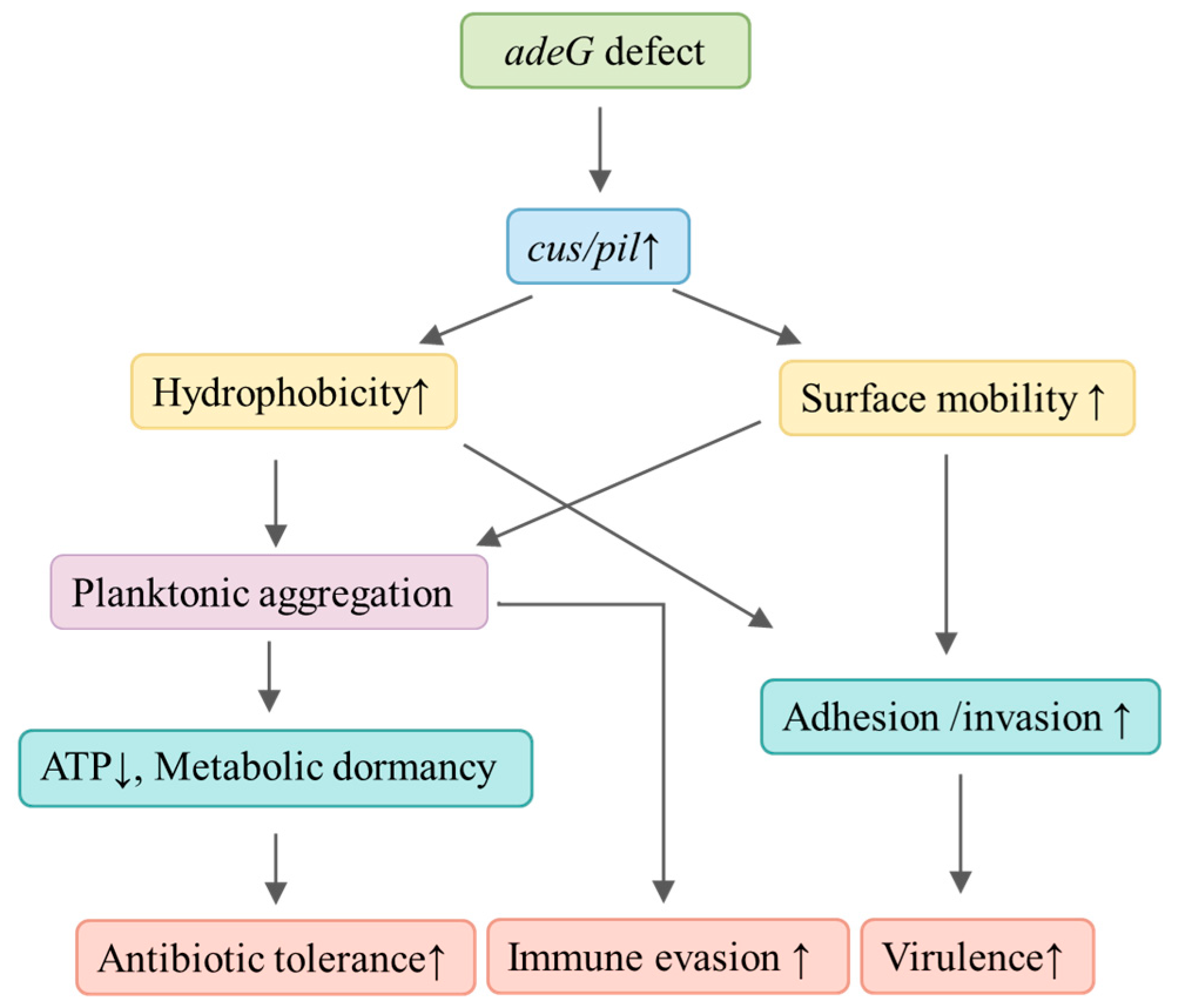

To clarify the regulatory network associated with

adeG deletion, we demonstrate that

adeG deficiency is linked to upregulation of the

csu/pil operon, enhancing both cell surface hydrophobicity and bacterial motility, which synergistically promote the formation of protein-dependent planktonic aggregates (

Figure 13). These aggregates act as a dual-functional hub: they induce ATP reduction and metabolic dormancy to boost antibiotic tolerance (e.g., against meropenem) while enriching

csu/pil-encoded fimbriae to strengthen host–cell adhesion/invasion and immune evasion—ultimately elevating bacterial virulence. Targeting aggregate matrices (e.g., Proteinase K, pilus-specific antibodies) could sensitize

A. baumannii to antibiotics. Inhibiting

csu operon expression may also prevent aggregation [

27]. However, future studies must validate these strategies in vivo, as Proteinase K’s host toxicity remains untested. This study has limitations: (1) other RND genes (e.g.,

adeB,

adeJ) may contribute to aggregation, requiring further investigation; (2) signaling pathways linking

adeG to

csu/

pil expression (e.g., BfmRS two-component system [

37]) remain unclear; (3) animal experiments used immunosuppressed mice aggregate function in immunocompetent hosts requires exploration.