Human Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence in the Canary Islands: Implications for One Health Surveillance and Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Climatology of the Archipelago

2.2. Serum Samples

2.3. Serological Methods

2.4. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

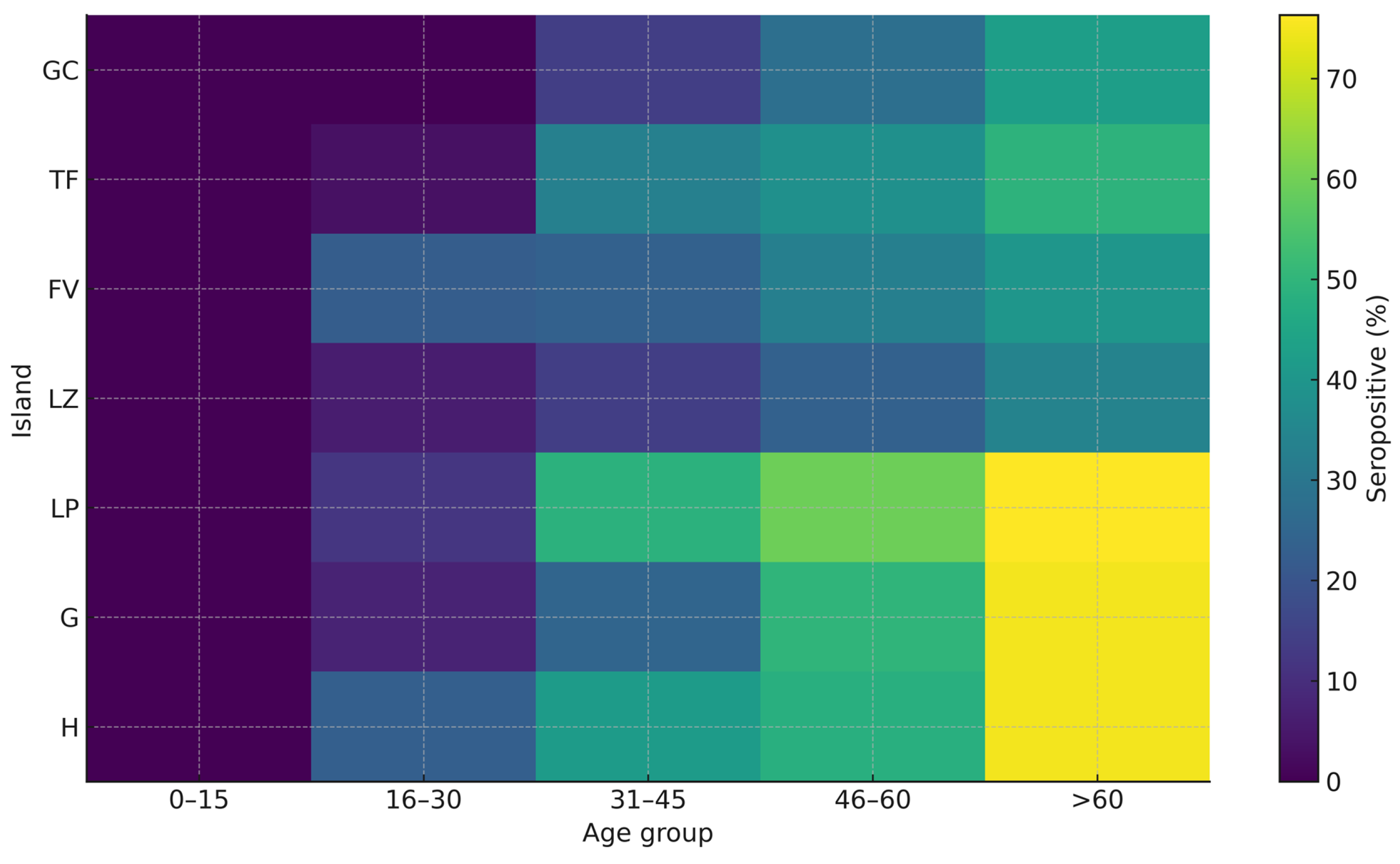

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robertson, L.J.; van der Giessen, J.W.B.; Batz, M.B.; Kojima, M.; Cahill, S. Have foodborne parasites finally become a global concern? Trends Parasitol. 2013, 29, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havelaar, A.H.; Kemmeren, J.M.; Kortbeek, L.M. Disease burden of congenital toxoplasmosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scallan, E.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Angulo, F.J.; Tauxe, R.V.; Widdowson, M.A.; Roy, S.L.; Jones, J.L.; Griffin, P.M. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—Major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Toxoplasmosis. 2014. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Miguel-Vicedo, M.; Cabello, P.; Ortega-Navas, M.C.; González-Barrio, D.; Fuentes, I. Prevalence of human toxoplasmosis in Spain throughout the three last decades (1993–2023): A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ponce, E.; Molina, J.M.; Hernández, S. Seroprevalence of goat toxoplasmosis on Grand Canary Island (Spain). Prev. Vet. Med. 1995, 24, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ponce, E.; Conde, M.; Corbera, J.A.; Jaber, J.R.; Ventura, M.R.; Gutiérrez, C. Serological survey of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum in goat population in Canary Islands (Macaronesia Archipelago, Spain). Small Rumin. Res. 2017, 147, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-Rodríguez, C.; Bolaños-Rivero, M.; Pérez-Arellano, J.-L. Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Humans: A Comprehensive Approach Involving the General Population, HIV-Infected Patients and Intermediate-Duration Fever in the Canary Islands, Spain. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, D.J.P. Identification of faecal transmission of Toxoplasma gondii: Small science, large characters. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.; Vesco, G.; Villari, S.; Buffolano, W. What do we know about risk factors for infection in humans with Toxoplasma gondii and how can we prevent infections? Zoonoses Public Health 2010, 57, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, J. Seroepidemiology of toxoplasmosis in the Lublin region. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2001, 8, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Ferreira, F.; Caldart, E.T.; Pasquali, A.K.S.; Mitsuka-Breganó, R.; Freire, R.L.; Navarro, I.T. Patterns of transmission and sources of infection in outbreaks of human toxoplasmosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 2177–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, P.; Rando, J.C. The number of pet cats (Felis catus) on a densely-populated oceanic island (Gran Canaria; Canary Archipelago) and its impact on wild fauna. J. Nat. Conserv. 2024, 79, 126587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbella, D.; Santana-Hernández, K.M.; Rodríguez-Ponce, E. Small islands as potential model ecosystems for parasitology: Climatic influence on parasites of feral cats. J. Helminthol. 2022, 96, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorta Antequera, P.; Díaz Pacheco, J.; López Díez, A.; Bethencourt Herrera, C. Tourism, transport and climate change: The carbon footprint of international air traffic on islands. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martín, R. (Ed.) Tourism Observatory of the Canary Islands: Preliminary Report; Cátedra de Turismo Caja Canarias-Ashotel de la Universidad de La Laguna: La Laguna, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzardo, O.P.; Hansen, A.; Martín-Cruz, B.; Macías-Montes, A.; Travieso-Aja, M.D.M. Integrating conservation and community engagement in free-roaming cat management: A case study from a Natura 2000 protected area. Animals 2025, 15, 429, Erratum in Animals 2025, 15, 1683.. [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda-Arias, J.C.; Gómez-Marin, J.E.; Bobić, B.; Naranjo-Galvis, C.A.; Djurković-Djaković, O. Toxoplasmosis as a travel risk. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2014, 12, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, E.D.; Carretón, E.; Morchón, R.; Falcón-Cordón, Y.; Falcón-Cordón, S.; Simón, F.; Montoya-Alonso, J.A. The Canary Islands as a model of risk of pulmonary dirofilariasis in a hyperendemic area. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Canario de Estadistica. Population Aged 16 to 69 by Activity Level (IPAQ), Genders and age Groups. The Canary Islands 2015. 2016. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/estadisticas/demografia/poblacion (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Bewick, V.; Cheek, L.; Ball, J. Statistics review 14: Logistic regression. Crit. Care 2005, 9, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Calero-Bernal, R.; Gennari, S.M.; Cano, S.; Salas-Fajardo, M.Y.; Ríos, A.; Álvarez-García, G.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in European residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published between 2000 and 2020. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesema, I.H.; Waap, H.; Swart, A.; Györke, A.; Le Roux, D.; Evangelista, F.M.; Spano, F.; Schares, G.; Deksne, G.; Gargaté, M.J.; et al. Systematic review and modelling of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence in humans, Europe, 2000 to 2021. Euro Surveill. 2025, 30, 2500069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, G.; Roussos, N.; Falagas, M.E. Toxoplasmosis snapshots: Global status of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence and implications for pregnancy and congenital toxoplasmosis. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, F.M.; Nogales, M. A review on the impacts of feral cats (Felis silvestris catus) in the Canary Islands: Implications for the conservation of its endangered fauna. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ponce, E.; González, J.F.; De Felipe, M.C.; Hernández, J.N.; Raduan Jaber, J. Epidemiological survey of zoonotic helminths in feral cats in Gran Canaria island (Macaronesian archipelago-Spain). Acta Parasitol. 2016, 61, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauss, C.B.L.; Almería, S.; Ortuño, A.; Garcia, F.; Dubey, J.P. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in domestic cats from Barcelona, Spain. J. Parasitol. 2003, 89, 1067–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, R.; Cabezón, O.; Millán, J.; Pabón, M.; Arnal, M.C.; Luco, D.F.; Gortázar, C.; Dubey, J.P.; Almería, S. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in wild carnivores from Spain. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 148, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Scholten, S.; Cano-Terriza, D.; Jiménez-Ruiz, S.; Almería, S.; Risalde, M.A.; Vicente, J.; Acevedo, P.; Arnal, M.C.; Balseiro, A.; Gómez-Guillamón, F.; et al. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii in wild ruminants in Spain. Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Fernández, N.; García-Dávila, P. El papel de los gatos en la toxoplasmosis. Rev. Fac. Med. UNAM 2017, 60, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; VanWormer, E.; Shapiro, K. More people, more cats, more parasites: Human population density and temperature variation predict prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii oocyst shedding in free-ranging domestic and wild felids. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofhuis, A.; van Pelt, W.; van Duynhoven, Y.T.; Nijhuis, C.D.; Mollema, L.; van der Klis, F.R.; Havelaar, A.H.; Kortbeek, L.M. Decreased prevalence and age-specific risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii IgG antibodies in The Netherlands between 1995/1996 and 2006/2007. Epidemiol. Infect. 2011, 139, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guigue, N.; Léon, L.; Hamane, S.; Gits-Muselli, M.; Le Strat, Y.; Alanio, A.; Bretagne, S. Continuous decline of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence in hospital: A 1997–2014 longitudinal study in Paris, France. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda, P.; Plata-Luis, J.; del Castillo-Figueruelo, B.; Fernández-Álvarez, Á.; Martín-Alonso, A.; Feliu, C.; Cabral, M.D.; Valladares, B. Serological survey of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii and Coxiella burnetii in rodents in north-Western African islands (Canary Islands and Cape Verde). Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2015, 82, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Alonso, J.A.; García-Rodríguez, S.N.; Matos, J.I.; Costa-Rodríguez, N.; Falcón-Cordón, Y.; Carretón, E.; Morchón, R. Change in the distribution pattern of Dirofilaria immitis in Gran Canaria (Hyperendemic Island) between 1994 and 2020. Animals 2024, 14, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P.; Beattie, C.P. Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Man; CRC Press: Boca Ratón, FL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.R.; Qiu, J.H.; Gao, J.F.; Liu, L.M.; Wang, C.; Liu, Q.; Yan, C.; Zhu, X.Q. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in sheep and goats in northeastern China. Small Rumin. Res. 2011, 97, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilking, H.; Thamm, M.; Stark, K.; Aebischer, T.; Seeber, F. Prevalence, incidence estimations, and risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection in Germany: A representative, cross-sectional, serological study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigna, J.J.; Tochie, J.N.; Tounouga, D.N.; Bekolo, A.O.; Ymele, N.S.; Youda, E.L.; Sime, P.S.; Nansseu, J.R. Global, regional, and country seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in pregnant women: A systematic review, modelling and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asencio, M.A.; Herraez, O.; Tenias, J.M.; Garduão, E.; Huertas, M.; Carranza, R.; Ramos, J.M. Seroprevalence survey of zoonoses in Extremadura, southwestern Spain, 2002–2003. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 68, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Ouellette, C.; Chen, K.; Moretto, M. Toxoplasma: Immunity and pathogenesis. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2019, 6, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, L.; Bahia-Oliveira, L.M.G.; Wada, M.Y.; Jones, J.L.; Tuboi, S.H.; Carmo, E.H.; Ramalho, W.M.; Camargo, N.J.; Trevisan, R.; Graça, R.M.T.; et al. Waterborne toxoplasmosis, Brazil, from field to gene. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baril, L.; Ancelle, T.; Goulet, V.; Thulliez, P.; Tirard-Fleury, V.; Carme, B. Risk factors for Toxoplasma infection in pregnancy: A case-control study in France. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 31, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhold, R.W.; Jessup, D.A. Zoonotic diseases associated with free-roaming cats. Zoonoses Public Health 2013, 60, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.U.; Rashid, I.; Akbar, H.; Islam, S.; Riaz, F.; Nabi, H.; Ashraf, K.; Singla, L.D. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in South Asian countries. Rev. Sci. Tech. OIE 2017, 36, 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Island/Sex | n | % | Missing Data | N | Mean Age ± SE | Min. Age | Max. Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gran Canaria (GC) | 115 | 9.0 | 7 | 108 | 39.58 ± 1.59 | 4 | 75 |

| Tenerife (TF) | 293 | 23.9 | 7 | 286 | 47.60 ± 1.02 | 2 | 91 |

| Fuerteventura (FV) | 249 | 20.1 | 8 | 241 | 41.95 ± 0.087 | 2 | 73 |

| Lanzarote (LZ) | 232 | 19.3 | 1 | 231 | 48.88 ± 0.87 | 12 | 86 |

| La Palma (LP) | 187 | 15.6 | - | 187 | 47.35 ± 1.11 | 8 | 80 |

| La Gomera (G) | 64 | 5.4 | - | 64 | 42.98 ± 1.65 | 10 | 83 |

| El Hierro (H) | 83 | 6.7 | 3 | 80 | 43.68 ± 1.62 | 2 | 82 |

| Total | 1223 | 100% | 26 | 1197 | 45.43 ± 0.044 | 2 | 91 |

| Age Group | 0–15 | 16–30 | 31–45 | 46–60 | >60 | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Island/sex | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M |

| Gran Canaria (GC) | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 29 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 5 | 9 | 58 | 50 |

| Tenerife (TF) | 3 | 3 | 19 | 11 | 60 | 45 | 43 | 33 | 44 | 25 | 169 | 117 |

| Fuerteventura (FV) | 6 | 4 | 8 | 23 | 47 | 63 | 26 | 41 | 12 | 11 | 99 | 142 |

| Lanzarote (LZ) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 30 | 41 | 37 | 64 | 18 | 23 | 89 | 142 |

| La Palma (LP) | 0 | 3 | 13 | 12 | 30 | 27 | 40 | 24 | 19 | 19 | 102 | 85 |

| La Gomera (G) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 17 | 2 | 2 | 21 | 43 |

| El Hierro (H) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 23 | 10 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 22 | 58 |

| N | 14 | 21 | 53 | 90 | 213 | 223 | 177 | 209 | 103 | 94 | 560 | 637 |

| T (%) | 35 (2.9) | 143 (11.9) | 436 (36.4) | 386 (32.2) | 197 (16.6) | 1197 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

González-Rodríguez, E.; Montoya-Alonso, J.A.; Santana-Hernández, K.M.; Carretón, E.; Ventura, M.R.; Rodríguez-Ponce, E. Human Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence in the Canary Islands: Implications for One Health Surveillance and Control. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010067

González-Rodríguez E, Montoya-Alonso JA, Santana-Hernández KM, Carretón E, Ventura MR, Rodríguez-Ponce E. Human Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence in the Canary Islands: Implications for One Health Surveillance and Control. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010067

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Rodríguez, Eligia, José Alberto Montoya-Alonso, Kevin M. Santana-Hernández, Elena Carretón, Myriam R. Ventura, and Eligia Rodríguez-Ponce. 2026. "Human Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence in the Canary Islands: Implications for One Health Surveillance and Control" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010067

APA StyleGonzález-Rodríguez, E., Montoya-Alonso, J. A., Santana-Hernández, K. M., Carretón, E., Ventura, M. R., & Rodríguez-Ponce, E. (2026). Human Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence in the Canary Islands: Implications for One Health Surveillance and Control. Microorganisms, 14(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010067