HS-Associated Pasteurella multocida Infection Disrupts Gut Microbiota and Metabolism in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Cultivation and Maintenance of Bacterial Strains

2.3. Animal Experiment and Sample Collection

2.4. Histological Observations

2.5. 16S rRNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.6. Samples Preparation and Metabolomics Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

3.1. NQ01 Infection Induces No Significant Changes in Murine Ileal Morphology

3.2. NQ01 Infection Alters the Profile of Gut Microbiota in Mice

3.3. NQ01 Reshapes the Composition and Abundance of Gut Microbiota in Mice

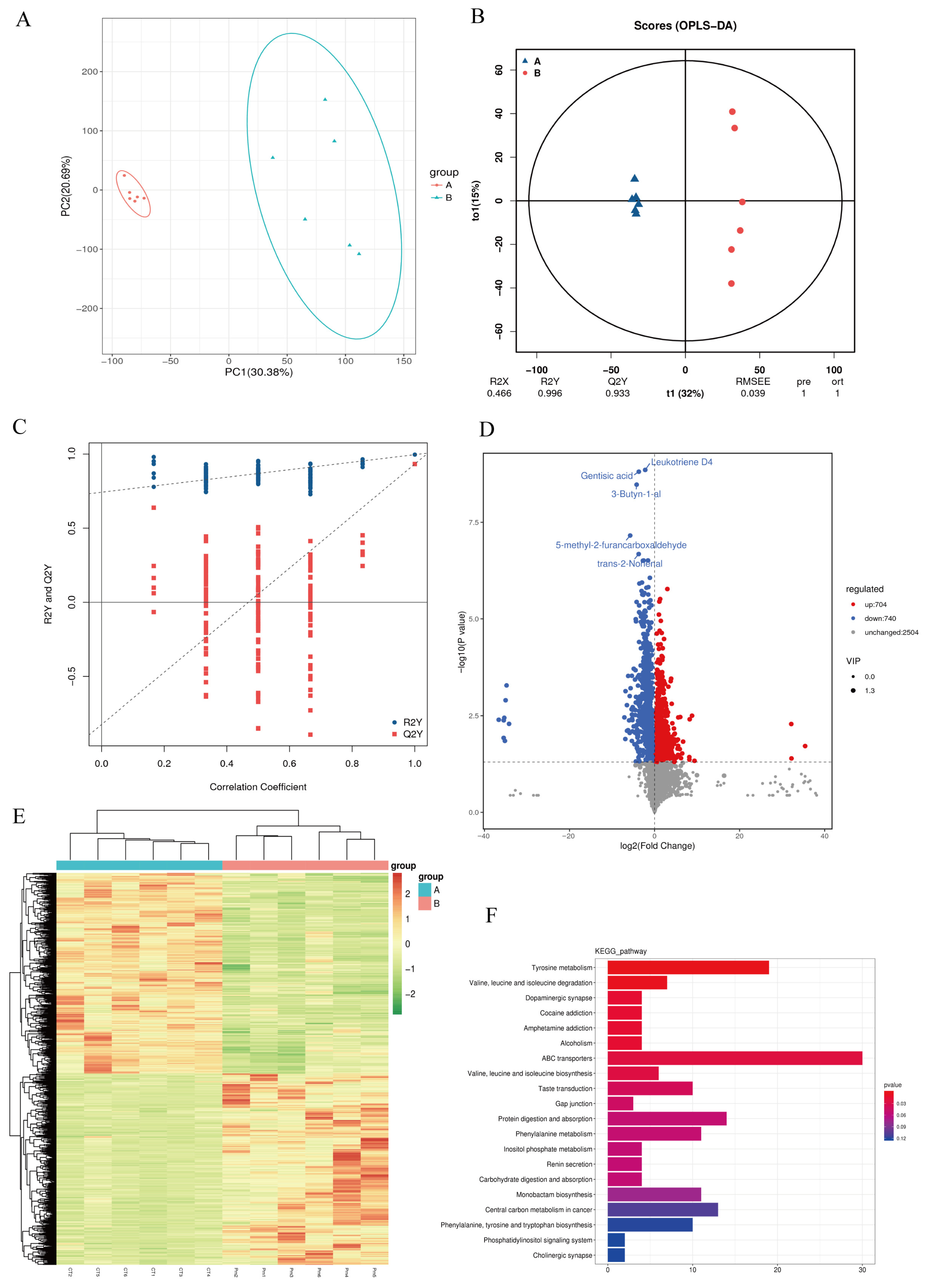

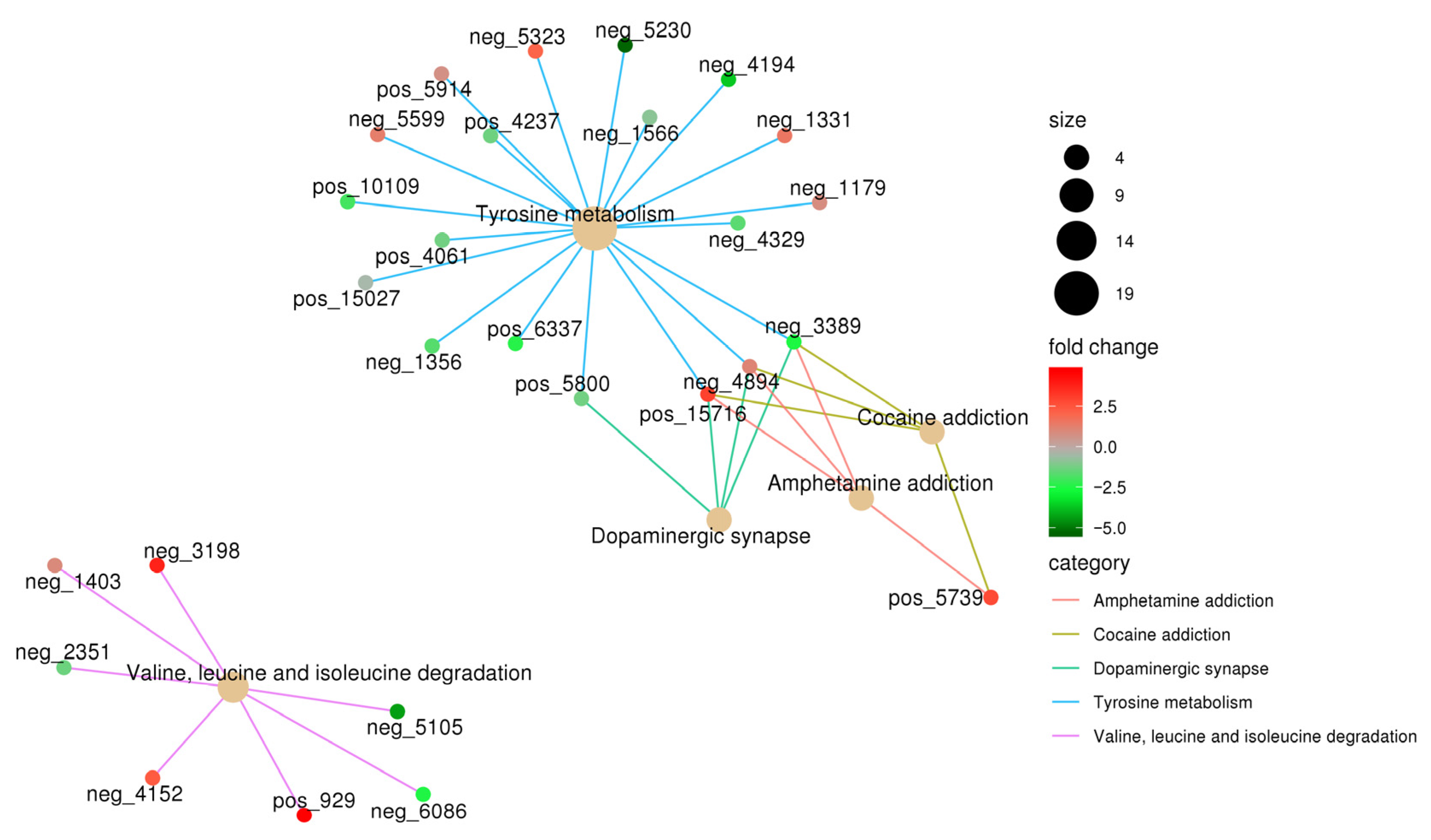

3.4. NQ01 Infection Disrupted the Gut Microbiota Metabolism in Mice

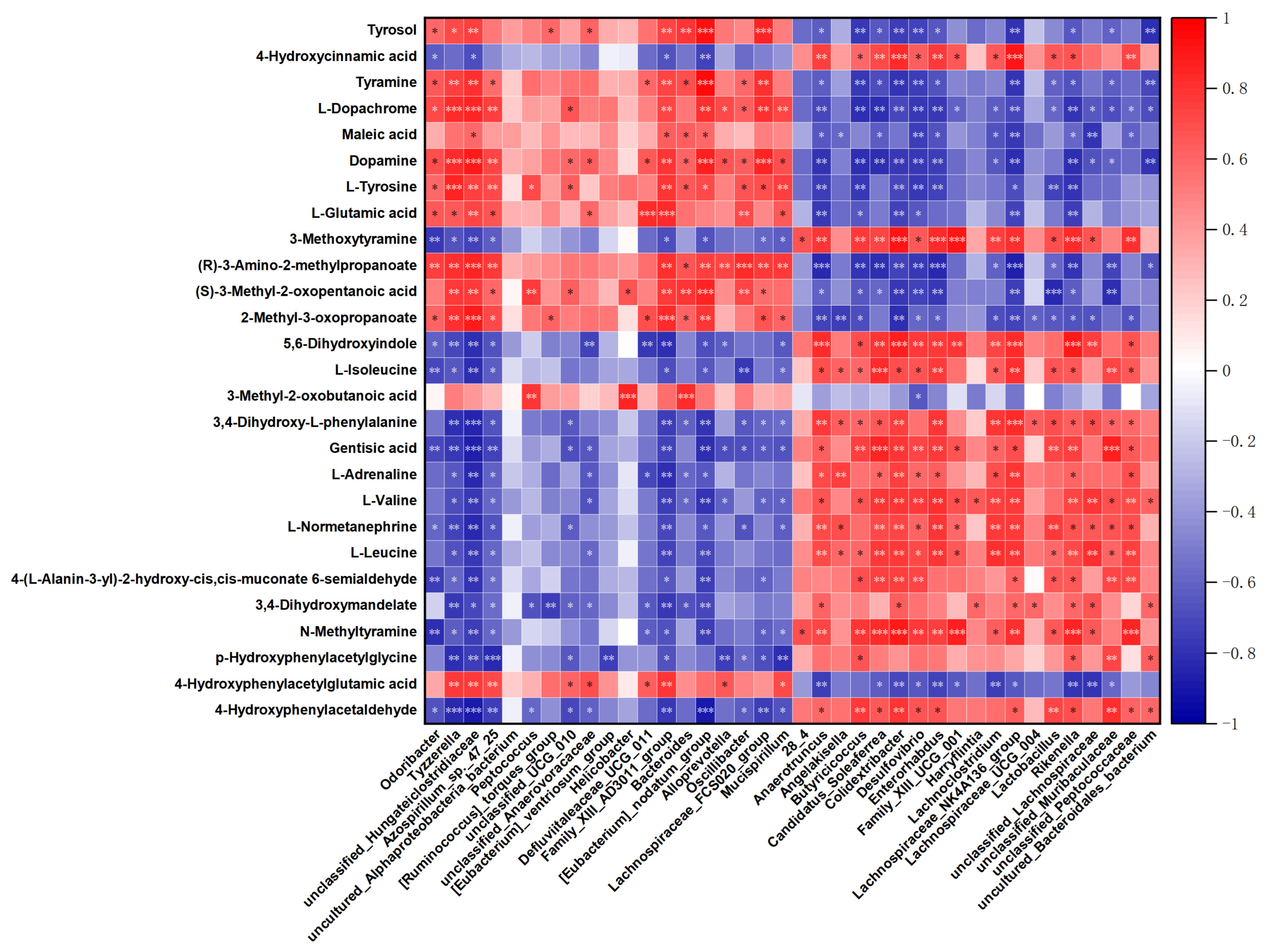

3.5. The Correlation Analysis for Differential Microbiota and Metabolites

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, R.; Chen, H.; Wilson, B.A.; Wu, B. Pasteurella multocida: Genotypes and Genomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2019, 83, e00014-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, G.R. Studies on Pasteurella multocida. I. A hemagglutination test for the identification of serological types. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1955, 16, 481–484. [Google Scholar]

- Heddleston, K.L.; Gallagher, J.E.; Rebers, P.A. Fowl cholera: Gel diffusion precipitin test for serotyping Pasteurella multocida from avian species. Avian Dis. 1972, 16, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, K.M.; Boyce, J.D.; Chung, J.Y.; Frost, A.J.; Adler, B. Genetic organization of Pasteurella multocida cap Loci and development of a multiplex capsular PCR typing system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabo, S.M.; Taylor, J.D.; Confer, A.W. Pasteurella multocida and bovine respiratory disease. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2007, 8, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, M.M.; Purse, B.V.; Hemadri, D.; Patil, S.S.; Yogisharadhya, R.; Prajapati, A.; Shivachandra, S.B. Spatial and temporal analysis of haemorrhagic septicaemia outbreaks in India over three decades (1987–2016). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoheer, R.; Abd Wahid, M.E.; Zakaria, H.A.; Jonet, M.A.B.; Al-Shaibani, M.M.; Al-Gheethi, A.; Addis, S.N.K. Spatial, Temporal, and Demographic Patterns in the Prevalence of Hemorrhagic Septicemia in 41 Countries in 2005–2019: A Systematic Analysis with Special Focus on the Potential Development of a New-Generation Vaccine. Vaccines 2022, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, T.D.; Khairullah, A.R.; Damayanti, R.; Mulyati, S.; Rimayanti, R.; Hernawati, T.; Utama, S.; Kusuma Wardhani, B.W.; Wibowo, S.; Ariani Kurniasih, D.A.; et al. Hemorrhagic septicemia: A major threat to livestock health. Open Vet. J. 2025, 15, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoades, K.R.; Heddleston, K.L.; Rebers, P.A. Experimental hemorrhagic septicemia: Gross and microscopic lesions resulting from acute infections and from endotoxin administration. Can. J. Comp. Med. Vet. Sci. 1967, 31, 226–233. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie, I.W.; Harper, M.; Boyce, J.D.; Adler, B. Pasteurella multocida: Diseases and pathogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012, 361, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcik, W.; Boutin, R.C.T.; Sokolowska, M.; Finlay, B.B. The Role of Lung and Gut Microbiota in the Pathology of Asthma. Immunity 2020, 52, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budden, K.F.; Gellatly, S.L.; Wood, D.L.; Cooper, M.A.; Morrison, M.; Hugenholtz, P.; Hansbro, P.M. Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut-lung axis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichinohe, T.; Pang, I.K.; Kumamoto, Y.; Peaper, D.R.; Ho, J.H.; Murray, T.S.; Iwasaki, A. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5354–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.L.; Sequeira, R.P.; Clarke, T.B. The microbiota protects against respiratory infection via GM-CSF signaling. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.C.; McConnell, K.W.; Yoseph, B.P.; Breed, E.; Liang, Z.; Clark, A.T.; O’Donnell, D.; Zee-Cheng, B.; Jung, E.; Dominguez, J.A.; et al. The endogenous bacteria alter gut epithelial apoptosis and decrease mortality following Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Shock 2012, 38, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cai, Y.; Garssen, J.; Henricks, P.A.J.; Folkerts, G.; Braber, S. The Bidirectional Gut-Lung Axis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 1145–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.L.; Liang, J.; Lin, S.Z.; Xie, Y.W.; Ke, C.H.; Ao, D.; Lu, J.; Chen, X.M.; He, Y.Z.; Liu, X.H.; et al. Gut-lung axis and asthma: A historical review on mechanism and future perspective. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2024, 14, e12356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana, J.K.; Aliberti, S.; Mac Aogáin, M.; Jaggi, T.K.; Ali, N.; Ivan, F.X.; Cheng, H.S.; Yip, Y.S.; Vos, M.I.G.; Low, Z.S.; et al. Microbial Dysregulation of the Gut-Lung Axis in Bronchiectasis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layeghifard, M.; Li, H.; Wang, P.W.; Donaldson, S.L.; Coburn, B.; Clark, S.T.; Caballero, J.D.; Zhang, Y.; Tullis, D.E.; Yau, Y.C.W.; et al. Microbiome networks and change-point analysis reveal key community changes associated with cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2019, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P.; Singer, B.H.; Newstead, M.W.; Falkowski, N.R.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Standiford, T.J.; Huffnagle, G.B. Enrichment of the lung microbiome with gut bacteria in sepsis and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Malmuthuge, N.; Yao, J.; Guan, L.L. Revisiting cattle respiratory health: Key roles of the gut-lung axis in the dynamics of respiratory tract pathobiome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2025, 89, e0018025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompette, A.; Gollwitzer, E.S.; Yadava, K.; Sichelstiel, A.K.; Sprenger, N.; Ngom-Bru, C.; Blanchard, C.; Junt, T.; Nicod, L.P.; Harris, N.L.; et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogard, G.; Makki, K.; Brito-Rodrigues, P.; Tan, J.; Molendi-Coste, O.; Barthelemy, J.; Descat, A.; Bouilloux, F.; Lecoeur, C.; Grangette, C.; et al. Impact of aging on gut-lung-adipose tissue interactions and lipid metabolism during influenza infection in mice. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Chou, H.C.; Huang, L.T.; Chen, C.M. Maternal Aspartame Exposure Induces Neonatal Pulmonary Metabolic Dysregulation and Redox Imbalance: A Multiomics Investigation of Gut Microbiota-Host Interactions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 27012–27024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yuan, H.; Jin, C.; Rahim, M.F.; Luosong, X.; An, T.; Li, J. Characterization and Genomic Analysis of Pasteurella multocida NQ01 Isolated from Yak in China. Animals 2025, 15, 3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Nageshwar Reddy, D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.-M.; et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180, Erratum in Nature 2014, 506, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, R.; Mathes, T.; Martens, E.C.; Kamada, N.; Nusrat, A.; Inohara, N.; Núñez, G. A specific gene-microbe interaction drives the development of Crohn’s disease-like colitis in mice. Sci. Immunol. 2019, 4, eaaw4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.L.; Zheng, J.M.; Shi, Z.Y.; Chen, H.H.; Wang, X.T.; Kong, F.B. Inflammatory proteins may mediate the causal relationship between gut microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease: A mediation and multivariable Mendelian randomization study. Medicine 2024, 103, e38551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Wu, X.; Chai, K.; Wang, S. Causal relationships between gut microbiota, immune cell, and Non-small cell lung cancer: A two-step, two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 1890–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, H.; Jamshaid, M.B.; Salahuudin, Z.; Sibtain, K.; Fayyaz, I.; Ameer, A.; Kerbiriou, C.; McKirdy, S.; Malik, S.N.; Gerasimidis, K.; et al. Gut microbial ecology and function of a Pakistani cohort with Iron deficiency Anemia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, R.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Yue, Z. Synergistic Toxicity of Combined Exposure to Acrylamide and Polystyrene Nanoplastics on the Gut-Liver Axis in Mice. Biology 2025, 14, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unrug-Bielawska, K.; Sandowska-Markiewicz, Z.; Piątkowska, M.; Czarnowski, P.; Goryca, K.; Zeber-Lubecka, N.; Dąbrowska, M.; Kaniuga, E.; Cybulska-Lubak, M.; Bałabas, A.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Gut Microbiota Responses to New SN-38 Derivatives, Irinotecan, and FOLFOX in Mice Bearing Colorectal Cancer Patient-Derived Xenografts. Cancers 2025, 17, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.S.; Li, S.; Cheng, X.; Tan, X.C.; Huang, Y.L.; Dong, H.J.; Xue, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.C.; Feng, X.X.; et al. Far-Infrared Therapy Based on Graphene Ameliorates High-Fat Diet-Induced Anxiety-Like Behavior in Obese Mice via Alleviating Intestinal Barrier Damage and Neuroinflammation. Neurochem. Res. 2024, 49, 1735–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, B.; Yin, J.; Liuqi, S.; Wang, J.; Peng, B.; Wang, S. Fucoidan Ameliorated Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis by Modulating Gut Microbiota and Bile Acid Metabolism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 14864–14876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Jiang, G.; Wang, Y.; Yan, E.; He, L.; Guo, J.; Yin, J.; Zhang, X. Maternal consumption of l-malic acid enriched diets improves antioxidant capacity and glucose metabolism in offspring by regulating the gut microbiota. Redox Biol. 2023, 67, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Yao, J.; Yu, J.; Liu, W.; Wu, L.; Wang, J.; Gao, R. Involvement of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in chronic restraint stress: Disturbances of the kynurenine metabolic pathway in both the gut and brain. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1869501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Xue, S.; Zhang, G.; Dang, Y.; Wang, H. Modulating the gut microbiota is involved in the effect of low-molecular-weight Glycyrrhiza polysaccharide on immune function. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2276814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirelli, E.; Pucci, M.; Squillario, M.; Bignotti, G.; Messali, S.; Zini, S.; Bugatti, M.; Cadei, M.; Memo, M.; Caruso, A.; et al. Effects of methylglyoxal on intestine and microbiome composition in aged mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 197, 115276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S.; Yang, Y.N.; Huo, J.X.; Sun, Y.Q.; Zhao, H.; Dong, X.T.; Feng, J.Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, C.M.; Li, Y.G. Cyanidin-3-rutinoside from Mori Fructus ameliorates dyslipidemia via modulating gut microbiota and lipid metabolism pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 137, 109834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Rimal, B.; Jiang, C.; Chiang, J.Y.L.; Patterson, A.D. Bile acid metabolism and signaling, the microbiota, and metabolic disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 237, 108238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.; Zhu, X.; Xu, B.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Yan, X. Integrated analysis of multi-tissues lipidome and gut microbiome reveals microbiota-induced shifts on lipid metabolism in pigs. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 10, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubner, S.C.; Le, T.; Wang, S. Tyrosine hydroxylase and regulation of dopamine synthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011, 508, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahn, S. The history of dopamine and levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, S497–S508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L.L.; Nikitin, M.A.; Poličar, P.G.; Kohn, A.B.; Romanova, D.Y. Evolution of glutamatergic signaling and synapses. Neuropharmacology 2021, 199, 108740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.; Elemba, E.; Zhong, Q.; Sun, Z. Gastrointestinal Interaction between Dietary Amino Acids and Gut Microbiota: With Special Emphasis on Host Nutrition. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2020, 21, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzine, C.; Loison, L.; Montbrion, N.; Bôle-Feysot, C.; Déchelotte, P.; Coëffier, M.; Ribet, D. Fatty acids produced by the gut microbiota dampen host inflammatory responses by modulating intestinal SUMOylation. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2108280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, T.P.; Pattaroni, C.; Perdijk, O.; Yap, C.; Trompette, A.; Anderson, D.; Creek, D.J.; Harris, N.L.; Marsland, B.J. Microbial metabolism of L-tyrosine protects against allergic airway inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, R.; Tang, J.; Zhu, J.; Aldrich, M.C.; Cox, N.J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, D. Cross-talks between gut microbiota and tobacco smoking: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ye, M.; Jin, H.; Chen, W.; Jieens, H.; Han, R. Relationship Between Gut Microbiota and Phenylalanine Levels: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Microbiologyopen 2025, 14, e70148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Name | log2FC | p Value | VIP | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pos6337 | 4-Hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde | −2.4 | 0.0001 | 1.67 | down |

| neg1356 | 5,6-Dihydroxyindole | −1.71 | 4.13 × 10−5 | 1.64 | down |

| pos15027 | 3,4-Dihydroxymandelate | −0.5 | 0.0210 | 1.16 | down |

| pos4061 | N-Methyltyramine | −1.31 | 0.0024 | 1.43 | down |

| pos10109 | 4-(L-Alanin-3-yl)-2-hydroxy-cis,cis-muconate 6-semialdehyde | −1.96 | 0.0065 | 1.36 | down |

| neg5599 | Tyrosol | 1.31 | 0.0466 | 1.09 | up |

| pos5914 | 4-Hydroxyphenylacetylglutamic acid | 0.72 | 0.0003 | 1.56 | up |

| pos4237 | p-Hydroxyphenylacetylglycine | −1.35 | 0.0107 | 1.24 | down |

| neg5323 | Tyramine | 2.06 | 0.0211 | 1.25 | up |

| neg5230 | L-Normetanephrine | −5.31 | 0.0030 | 1.53 | down |

| neg1566 | 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid | −0.92 | 0.0127 | 1.29 | down |

| neg4194 | Gentisic acid | −3.7 | 1.55 × 10−9 | 1.76 | down |

| neg1331 | L-Dopachrome | 1.49 | 0.0024 | 1.54 | up |

| neg1179 | Maleic acid | 0.81 | 0.0187 | 1.26 | up |

| neg4329 | L-Adrenaline | −1.63 | 0.0038 | 1.42 | down |

| neg3389 | 3,4-Dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine | −2.56 | 1.28 × 10−5 | 1.69 | down |

| neg4894 | Dopamine | 1.09 | 0.0112 | 1.39 | up |

| pos15716 | L-Tyrosine | 2.99 | 0.0105 | 1.33 | up |

| pos5800 | 3-Methoxytyramine | −1.3 | 0.0054 | 1.36 | down |

| pos5739 | L-Glutamic acid | 2.77 | 0.0103 | 1.24 | up |

| neg3198 | 3-Methyl-2-oxobutanoic acid | 3.77 | 0.0421 | 1.15 | up |

| neg1403 | (R)-3-Amino-2-methylpropanoate | 0.92 | 0.0003 | 1.53 | up |

| neg2351 | L-Isoleucine | −1.38 | 0.0013 | 1.47 | down |

| neg4152 | (S)-3-Methyl-2-oxopentanoic acid | 2.33 | 0.0094 | 1.39 | up |

| pos929 | 2-Methyl-3-oxopropanoate | 4.63 | 0.0096 | 1.45 | up |

| neg6086 | L-Leucine | −2.5 | 0.0022 | 1.5 | down |

| neg5105 | L-Valine | −4.37 | 0.0011 | 1.6 | down |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, K.; Jin, C.; Yuan, H.; Rahim, M.F.; Luosong, X.; An, T.; Li, J. HS-Associated Pasteurella multocida Infection Disrupts Gut Microbiota and Metabolism in Mice. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010066

Li K, Jin C, Yuan H, Rahim MF, Luosong X, An T, Li J. HS-Associated Pasteurella multocida Infection Disrupts Gut Microbiota and Metabolism in Mice. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010066

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Kewei, Chao Jin, Haofang Yuan, Muhammad Farhan Rahim, Xire Luosong, Tianwu An, and Jiakui Li. 2026. "HS-Associated Pasteurella multocida Infection Disrupts Gut Microbiota and Metabolism in Mice" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010066

APA StyleLi, K., Jin, C., Yuan, H., Rahim, M. F., Luosong, X., An, T., & Li, J. (2026). HS-Associated Pasteurella multocida Infection Disrupts Gut Microbiota and Metabolism in Mice. Microorganisms, 14(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010066