Isolation and Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa XR2-39 Against Meloidogyne incognita and Its Enhancement of Tomato Growth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and M. incognita Inoculum

2.2. Isolation of Biocontrol Bacterial Strains Against M. incognita

2.3. Nematocidal Activity of Bacterial Fermentation Filtrates Against J2s of M. incognita In Vitro

2.4. Identification and Characterization of Plant Growth-Promoting (PGR) Traits of XR2-39

2.4.1. Molecular Identification of Strain XR2-39 Against M. incognita

2.4.2. Biochemical Characterization of Strain XR2-39

2.4.3. IAA Production

2.4.4. Phosphate Solubilization

2.4.5. Siderophore Production

2.5. Effect of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Filtrate on J2s, Egg Mass, and Free Egg Hatching of M. incognita

2.5.1. Effects of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Filtrates on J2s of M. incognita In Vitro

2.5.2. Effects of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Filtrates on Egg Masses In Vitro

2.5.3. Effects of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Filtrates on Free Eggs In Vitro

2.6. Effect of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Broth on Growth of Tomato Plants in Pot Experiment

2.7. Biocontrol of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Broth Against M. incognita on Tomato Plants in a Pot

2.8. Effect of pH, Temperature, and UV Irradiation and Storage on Stability of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Filtrate

3. Results

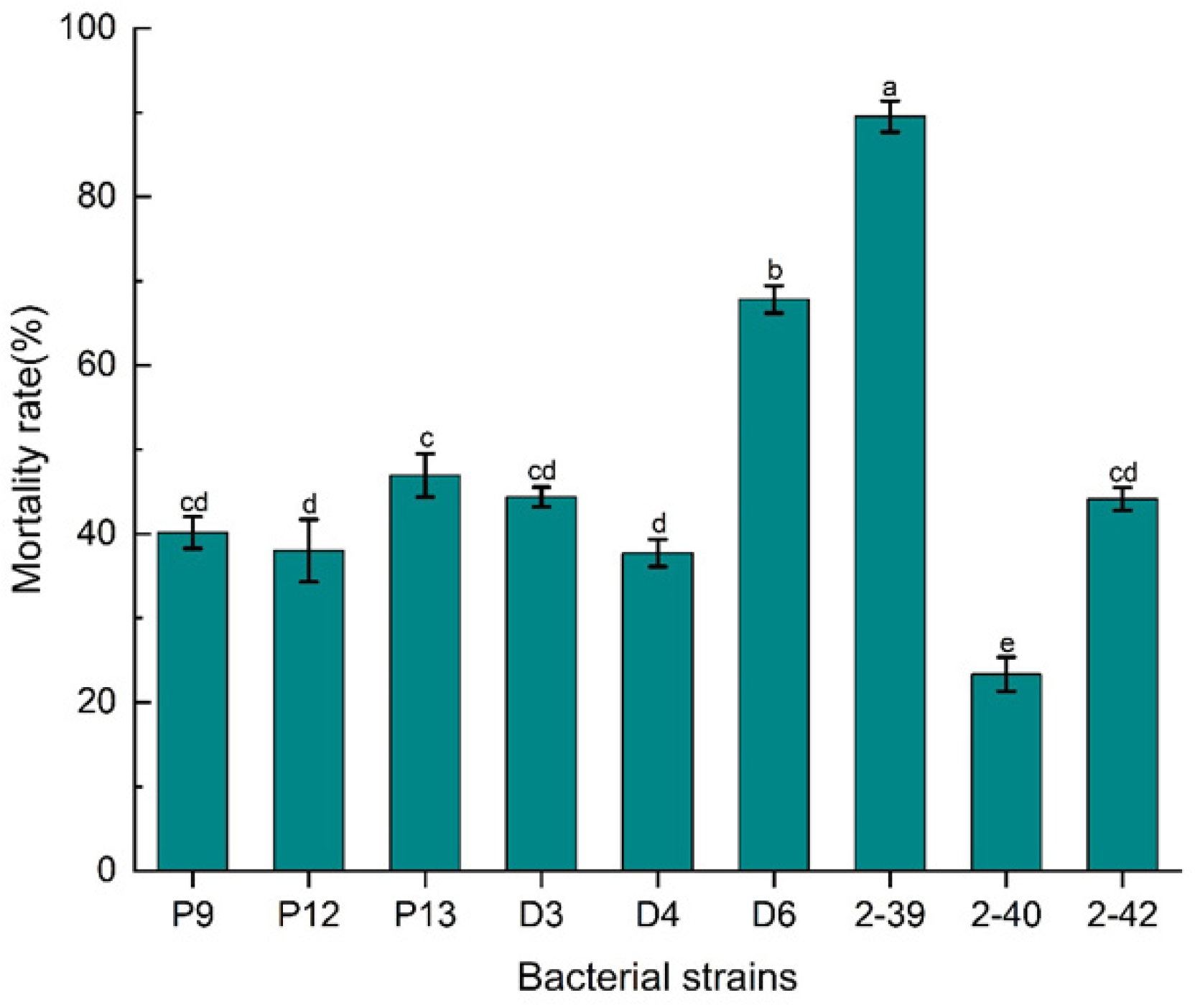

3.1. Isolation of Biocontrol Bacterial Strain XR2-39 Against M. incognita

3.2. Identification and Characterization of Plant Growth-Promoting (PGR) Traits of XR2-39

3.3. Nematocidal Activity of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Filtrate Against M. incognita J2s In Vitro

3.4. Effect of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Filtrate on Egg Mass and Free Egg Hatching of M. incognita

3.5. Effect of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Broth on Growth of Tomato Plants in Pot Experiment

3.6. Effect of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Broth Against M. incognita in Pot Plants

3.7. Effect of pH, Temperature, and Ultraviolet Irradiation and Storage on Stability of Strain XR2-39 Fermentation Filtrate

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elling, A.A. Major emerging problems with minor Meloidogyne species. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.T.; Haegeman, A.; Danchin, E.G.J.; Gaur, H.S.; Helder, J.; Jones, M.G.K.; Kikuchi, T.; Manzanilla-López, R.; Palomares-Rius, J.E.; Wesemael, W.M.L.; et al. Top 10 plant-parasitic nematodes in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 946–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Fan, H.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, D.; Duan, Y.; Chen, L. Multifunctional efficacy of the nodule endophyte Pseudomonsa fragi in stimulating tomato immune response against Meloidogyne incognita. Biol. Control 2021, 164, 104773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, P.; Favery, B.; Rosso, M.N.; Castagnone-Sereno, P. Root-knot nematode parasitism and host response: Molecular basis of a sophisticated interaction. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2003, 4, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitiku, M. Plant-parasitic nematodes and their management: A review. Agric. Res. Technol. 2018, 8, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, L.; Khan, R.A.A.; Song, X.; Najeeb, S.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Ling, J.; Mao, Z.; Jiang, X.; et al. Methylorubrum rhodesianum M520 as a biocontrol agent against Meloidogyne incognita (Tylenchida: Heteroderidae) J2s infecting cucumber roots. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiewnick, S.; Sikora, R.A. Evaluation of Paecilomyces lilacinus strain 251 for the biological control of the northern root-knot nematode Meloidogyne hapla Chitwood. Nematology 2006, 8, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, M.; Perry, R.N.; Starr, J.L. Meloidogyne Species—A Diverse Group of Novel and Important Plant Parasites; Perry, R.N., Moens, M., Starr, J.L., Eds.; Root-Knot Nematodes; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S.M.; Rosskopf, E.N.; Leesch, J.G.; Chellemi, D.O.; Bull, C.T.; Mazzola, M. United states department of agriculture-agricultural research service research on alternatives to methyl bromide: Pre-plant and post-harvest. Pest Manag. Sci. 2003, 59, 814–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani, F.; Hajihassani, A. Recent advances in the development of environmentally benign treatments to control root-knot nematodes. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, N.; Liu, R.; Zhao, J.L.; Khan, R.A.A.; Mao, Z. Volatile organic compounds of Bacillus cereus strain Bc-cm103 exhibit fumigation activity against Meloidogyne incognita. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.; Askary, T.H. Fungal and bacterial nematicides in integrated nematode management strategies. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2018, 28, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, R.S.; Patil, J.A.; Yadav, S. Prospects of using predatory nematodes in biological control for plant parasitic nematodes—A review. Biol. Control 2021, 160, 104668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.A.; Najeeb, S.; Mao, Z.; Ling, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xie, B. Bioactive secondary metabolites from Trichoderma spp. against phytopathogenic bacteria and root-knot nematode. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, C.; Nie, X.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Sun, M.; Peng, D. A novel serine protease, Sep1, from Bacillus firmus DS-1 has nematicidal activity and degrades multiple intestinal-associated nematode proteins. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalanathan, V.; Sevugapperumal, N.; Nallusamy, S. Antagonistic bacteria Bacillus velezensis VB7 possess nematicidal action and induce an immune response to suppress the infection of root-knot nematode (RKN) in tomato. Genes 2023, 14, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, B.-M.; Lee, H.C.; Choi, I.-S.; Koo, K.-B.; Son, K.-H. Antagonistic efficacy of symbiotic bacterium Xenorhabdus sp. SCG against Meloidogyne spp. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.; Lade, H. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria to improve crop growth in saline soils: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Jha, D.K. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): Emergence in agriculture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 1327–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, J.J.F.; Labuschagne, N.; Fourie, H.; Sikora, R.A. Biological control of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita on tomatoes and carrots by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2019, 44, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, B.; Ahmed, R.; Hussain, M.; Phukon, P.; Wann, S.B.; Sarmah, D.K.; Bhau, B.S. Suppression of root-knot disease in Pogostemon cablin caused by Meloidogyne incognita in a rhizobacteria mediated activation of phenylpropanoid pathway. Biol. Control 2018, 119, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetintas, R.; Kusek, M.; Fateh, S.A. Effect of some plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria strains on root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita, on tomatoes. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2018, 28, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; You, J.; Wang, Y.; Long, Y.; Wang, S.; Pan, F.; Yu, Z. Biocontrol efficacy of Bacillus velezensis strain YS-AT-DS1 against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita in tomato plants. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1035748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Qi, G.; Yin, R.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Zhao, X. Bacillus cereus strain S2 shows high nematicidal activity against Meloidogyne incognita by producing sphingosine. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Gao, Q.; Ji, C.; Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Liu, X. Bacillus licheniformis JF-22 to control Meloidogyne incognita and its effect on tomato rhizosphere microbial community. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 863341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bel, Y.; Galeano, M.; Baños-Salmeron, M.; Andrés-Antón, M.; Escriche, B. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry5, Cry21, App6 and Xpp55 proteins to control Meloidogyne javanica and M. incognita. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhai, H.; Dong, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, Y. Bacillus velezensis A-27 as a potential biocontrol agent against Meloidogyne incognita and effects on rhizosphere communities of celery in field. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ouyang, J.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Rehman, M.; Deng, G.; Shu, J.; Zhao, D.; Chen, S.; Sayyed, R.Z.; et al. Nematicidal activity of Burkholderia arboris J211 against Meloidogyne incognita on tobacco. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 915546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, B.-M.; Kang, M.-K.; Park, D.-J.; Choi, I.-S.; Park, H.-Y.; Lim, C.-H.; Son, K.-H. Assessment of nematicidal and plant growth-promoting effects of Burkholderia sp. JB-2 in root-knot nematode-infested soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1216031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucky, T.; Hochstrasser, M.; Meyer, S.; Segessemann, T.; Ruthes, A.C.; Ahrens, C.H.; Pelludat, C.; Dahlin, P. A novel robust screening assay identifies Pseudomonas strains as reliable antagonists of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Aal, E.M.; Shahen, M.; Sayed, S.; Kesba, H.; Ansari, M.J.; El-Ashry, R.M.; Aioub, A.A.A.; Salma, A.S.A.; Eldeeb, A.M. In vivo and in vitro management of Meloidogyne incognita (Tylenchida: Heteroderidae) using rhizosphere bacteria, Pseudomonas spp. and Serratia spp. compared with oxamyl. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 4876–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, M.; Kokalis-Burelle, N.; Lawrence, K.; van Santen, E.; Kloepper, J. Suppressiveness of root-knot nematodes mediated by rhizobacteria. Biol. Control 2008, 47, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hadad, M.E.; Mustafa, M.I.; Selim, S.M.; El-Tayeb, T.S.; Mahgoob, A.E.A.; Aziz, N.H.A. The nematicidal effect of some bacterial biofertilizers on Meloidogyne incognita in sandy soil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2011, 42, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nardo, E.A.B.; Grewal, P.S. Compatibility of Steinernema feltiae (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) with pesticides and plant growth regulators used in glasshouse plant production. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2003, 13, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.Q.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Q.; Hao, G.Y.; Liang, C.; Duan, F.M.; Zhao, H.G.; Song, W.W. Biocontrol efficacy and induced resistance of Paenibacillus polymyxa J2-4 against Meloidogyne incognita infection in cucumber. Biol. Control Microb. Ecol. 2024, 114, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R.E.; Gibbons, N.E. Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, 8th ed.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, X.F.; Wang, Y.Y.; Duan, Y.X.; Xuan, Y.X.; Chen, L.J. Isolation and identification of bacteria from rhizosphere soil and their effect on plant growth promotion and root-knot nematode disease. Biol. Control 2018, 119, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ei, S.L.; Lwin, K.M.; Padamyar; Khaing, H.O.; Yu, S.S. Study on IAA Producing Rhizobacterial Isolates and Their Effect in Talc-Based Carrier on Some Plants. J. Soil Sci. Plant Health 2018, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.W.; Bonner, J. The enzymatic inactivation of indole acetic acid. II. The physiology of the enzyme. Am. J. Bot. 1948, 35, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.A.; Weber, R.P. Colorimetric estimation of inodole3-acetic acid. Plant Physiol. 1951, 26, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, X.L.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, S.Q. Construction of phosphate-solubilizing microbial consortium and its effect on the remediation of saline-alkali soil. Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussey, R.S.; Barker, K.R. A comparison of methods of collecting inocula of Meloidogyne spp. Including a new technique. Plant Dis. Rep. 1973, 57, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, J.; Page, S.L. Estimation of root-knot nematode infestation levels on roots using a rating chart. Int. J. Pest Manag. 1980, 26, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Ali, Q.; Farzand, A.; Khan, A.R.; Ling, H.; Gao, X. Nematicidal volatiles from Bacillus atrophaeus GBSC56 promote growth and stimulate induced systemic resistance in tomato against Meloidogyne incognita. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saharan, R.; Patil, J.A.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, A.; Goyal, V. The nematicidal potential of novel fungus, Trichoderma asperellum FbMi6 against Meloidogyne incognita. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.P.; Sharma, A.K. Effective control of root-knot nematode disease with Pseudomonad rhizobacteria filtrate. Rhizosphere 2017, 3, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Haris, M.; Shakeel, A.; Ahmad, G.; Khan, G.A.; Khan, M.A. Bio-nematicidal activities by culture filtrate of Bacillus subtilis HussainT-AMU: New promising biosurfactant bioagent for the management of Root Galling caused by Meloidogyne incognita. Vegetos 2020, 33, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Shao, Z.; Cai, M.; Zheng, L.; Li, G.; Huang, D.; Cheng, W.; Thomashow, L.S.; Weller, D.M.; Yu, Z.; et al. Multiple modes of nematode control by volatiles of Pseudomonas putida 1A00316 from Antarctic soil against Meloidogyne incognita. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.S.; Kamalnath, M.; Umamaheswari, R.; Rajinikanth, R.; Prabu, P.; Priti, K.; Grace, G.N.; Chaya, M.K.; Gopalakrishnan, C. Bacillus subtilis IIHR BS-2 enriched vermicompost controls root knot nematode and soft rot disease complex in carrot. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 218, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, N.; Zhao, J.L.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Ling, J.; Yang, Y.H.; Xie, B.Y.; Mao, Z.C. Biocontrol efficacy of Bacillus cereus strain Bc-cm103 against Meloidogyne incognita. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Akanda, A.M.; Prova, A.; Islam, M.T.; Hossain, M.M. Isolation and identification of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from cucumber rhizosphere and their effect on plant growth promotion and disease suppression. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamsuk, K.; Dell, B.; Pathom-Aree, W.; Pathaichindachote, W.; Suphrom, N.; Nakaew, N.; Jumpathong, J. Screening plant growth-promoting bacteria with antimicrobial properties for upland rice. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbel, S.; Aldilami, M.; Zouari-Mechichi, H.; Mechichi, T.; AlSherif, E.A. Isolation and characterization of a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium strain MD36 that promotes barley seedlings and growth under heavy metals stress. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.T.; Tani, A.; Khew, C.Y.; Chua, Y.Q.; Hwang, S.S. Plant growth-promoting bacteria as potential bio-inoculants and biocontrol agents to promote black pepper plant cultivation. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 240, 126549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolu, H.; Killi, D.; Bas, S.; Bilecen, D.S.; Seymen, M. Effectiveness of salt priming and plant growth-promoting bacteria in mitigating salt-induced photosynthetic damage in melon. Photosynth. Res. 2025, 163, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaepen, S.; Bossuyt, S.; Engelen, K.; Marchal, K.; Vanderleyden, J. Phenotypical and molecular responses of Arabidopsis thaliana roots as a result of inoculation with the auxin-producing bacterium Azospirillum brasilense. New Phytol. 2014, 201, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, O.M.; Salas-González, I.; Castrillo, G.; Conway, J.M.; Law, T.F.; Teixeira, P.J.P.L.; Wilson, E.D.; Fitzpatrick, C.R.; Jones, C.D.; Dangl, J.L. A single bacterial genus maintains root growth in a complex microbiome. Nature 2020, 587, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, M.; Gulluce, M.; Von Wirén, N.; Sahin, F. Yield promotion and phosphorus solubilization by plant growth–promoting rhizobacteria in extensive wheat production in Turkey. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2012, 175, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, P.; Crowley, D.; Rengel, Z. Rhizosphere interactions between microorganisms and plants govern iron and phosphorus acquisition along the root axis—Model and research methods. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniguez, A.L.; Dong, Y.; Triplett, E.W. Nitrogen fixation in wheat provided by Klebsiella pneumoniae 342. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2004, 17, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.B.; Sahai, V.; Goyal, D.; Prasad, M.; Yadav, A.; Shrivastav, P.; Ali, A.; Dantu, P.K. Identification, characterization and evaluation of multifaceted traits of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from soil for sustainable approach to agriculture. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 3633–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed Ab Rahman, S.F.; Singh, E.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Schenk, P.M. Emerging microbial biocontrol strategies for plant pathogens. Plant Sci. 2018, 267, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Wang, J.-Y.; Liu, X.-F.; Guan, Q.; Dou, N.-X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, Y.-M.; Wang, M.; Li, J.-S.; et al. Nematicidal activity of volatile organic compounds produced by Bacillus altitudinis AMCC 1040 against Meloidogyne incognita. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Biochemical Test | Test Result |

|---|---|

| Gram staining | − |

| Catalase activity | + |

| Glycolysis | − |

| Nitrate reduction | + |

| Starch hydrolysis | + |

| Gelatin hydrolysis | + |

| Indole test | − |

| Citrate utilization | + |

| MR test | − |

| VP test | − |

| H2S production | − |

| IAA production (mg/L) | 33.01 ± 1.36 |

| Phosphate Solubilization (mg/L) | 831.15 ± 21.40 |

| Siderophore production (%) | 71.45 ± 2.51 |

| Treatment | Egg Mass (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 d | 2 d | 3 d | 4 d | 5 d | |

| 100% Fermentation filtrate | 97.87 ± 2.71 a | 100 ± 0.001 a | 100 ± 0.00 a | 100 ± 0.00 a | 100 ± 0.00 a |

| 20% Fermentation filtrate | 73.91 ± 6.07 b | 91.26 ± 2.60 b | 90.30 ± 4.19 b | 95.10 ± 2.45 a | 96.52 ± 3.25 ab |

| 10% Fermentation filtrate | 59.82 ± 4.52 c | 77.11 ± 4.21 c | 83.64 ± 8.51 b | 87.48 ± 8.47 b | 87.15 ± 1.13 b |

| 5% Fermentation filtrate | 43.02 ± 1.40 d | 64.28 ± 6.28 d | 65.72 ± 6.47 c | 63.8 ± 1.19 c | 65.47 ± 11.00 c |

| Free egg (%) | |||||

| 100% Fermentation filtrate | 100 ± 0.00 a | 99.13 ± 1.73 a | 100 ± 0.00 a | 100 ± 0.00 a | 100 ± 0.00 a |

| 20% Fermentation filtrate | 47.16 ± 5.80 b | 56.60 ± 8.35 b | 70.82 ± 5.50 b | 75.11 ± 5.11 b | 75.93 ± 8.44 b |

| 10% Fermentation filtrate | 36.29 ± 3.77 c | 38.22 ± 7.02 c | 57.16 ± 2.02 c | 68.70 ± 6.29 b | 70.58 ± 7.59 b |

| 5% Fermentation filtrate | 30.18 ± 6.49 c | 36.20 ± 1.17 c | 49.62 ± 6.99 c | 51.73 ± 9.35 c | 48.68 ± 5.99 c |

| Treatment | Shoot Length (cm) | Fresh Shoot Weight (g) | Root Weight (g) | Stem Diameter (cm) | Root Length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% Fermentation | 11.97 ± 0.39 b | 1.32 ± 0.37 b | 0.15 ± 0.06 b | 0.33 ± 0.03 a | 6.50 ± 2.55 a |

| 20% Fermentation | 19.55 ± 1.39 a | 1.92 ± 1.57 a | 0.26 ± 0.03 a | 0.33 ± 0.01 a | 4.93 ± 1.01 abc |

| 10% Fermentation | 10.93 ± 1.04 b | 0.55 ± 0.43 c | 0.13 ± 0.01 b | 0.26 ± 0.02 b | 5.77 ± 1.45 ab |

| 5% Fermentation | 7.72 ± 0.58 c | 0.37 ± 0.15 c | 0.11 ± 0.04 b | 0.24 ± 0.03 b | 4.00 ± 0.70 bc |

| Water control | 7.00 ± 1.39 c | 0.35 ± 0.1 c | 0.11 ± 0.05 b | 0.21 ± 0.03 c | 3.30 ± 1.19 c |

| Treatment | Shoot Length (cm) | Fresh Shoot Weight (g) | Root Length (cm) | Root Weight (g) | Stem Diameter (cm) | Root-Knot Index | Biocontrol Effect (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abamectin | 30.09 ± 2.20 a | 7.59 ± 0.56 a | 7.18 ± 1.10 ab | 0.50 ± 0.11 a | 0.44 ± 0.04 a | 29.00 ± 0.05 c | 62.36 |

| 20% XR2-39 fermentation | 30.48 ± 0.65 a | 6.29 ± 0.18 b | 8.06 ± 0.67 a | 0.48 ± 0.07 a | 0.42 ± 0.02 a | 37.00 ± 0.08 b | 52.44 |

| Water control | 29.17 ± 0.62 a | 4.75 ± 0.16 c | 6.51 ± 0.67 b | 0.43 ± 0.08 a | 0.37 ± 0.01 b | 77.50 ± 0.05 a | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, M.; Li, W.; Fan, L.; Zhang, F.; Wu, C.; Xu, X.; Yao, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, S.; Yao, J. Isolation and Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa XR2-39 Against Meloidogyne incognita and Its Enhancement of Tomato Growth. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010005

Yuan M, Li W, Fan L, Zhang F, Wu C, Xu X, Yao Y, Zhu Z, Li S, Yao J. Isolation and Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa XR2-39 Against Meloidogyne incognita and Its Enhancement of Tomato Growth. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Mengyu, Wuping Li, Linjuan Fan, Fan Zhang, Caiyun Wu, Xueliang Xu, Yingjuan Yao, Zhihui Zhu, Shaoqin Li, and Jian Yao. 2026. "Isolation and Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa XR2-39 Against Meloidogyne incognita and Its Enhancement of Tomato Growth" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010005

APA StyleYuan, M., Li, W., Fan, L., Zhang, F., Wu, C., Xu, X., Yao, Y., Zhu, Z., Li, S., & Yao, J. (2026). Isolation and Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa XR2-39 Against Meloidogyne incognita and Its Enhancement of Tomato Growth. Microorganisms, 14(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010005