Inter-Row Grassing Reshapes Nitrogen Cycling in Peach Orchards by Influencing Microbial Pathways in the Rhizosphere

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Soil Sampling

2.2. Soil Physicochemical Analyses

2.3. Soil DNA Extraction, Metagenomic Sequencing, and Bioinformatic Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

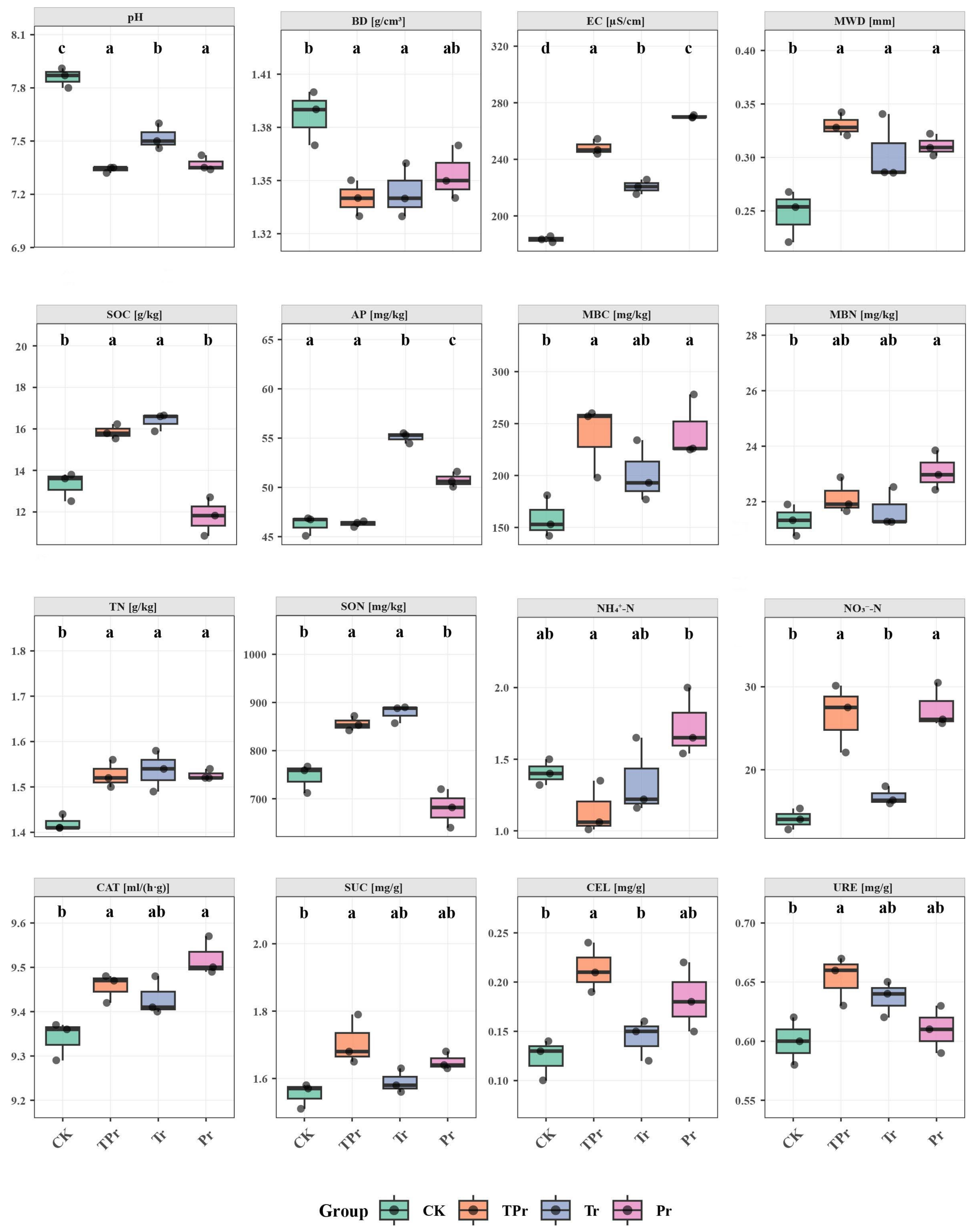

3.1. Effects of Grass Species Configuration on Soil Physicochemical Properties in the Peach Orchard

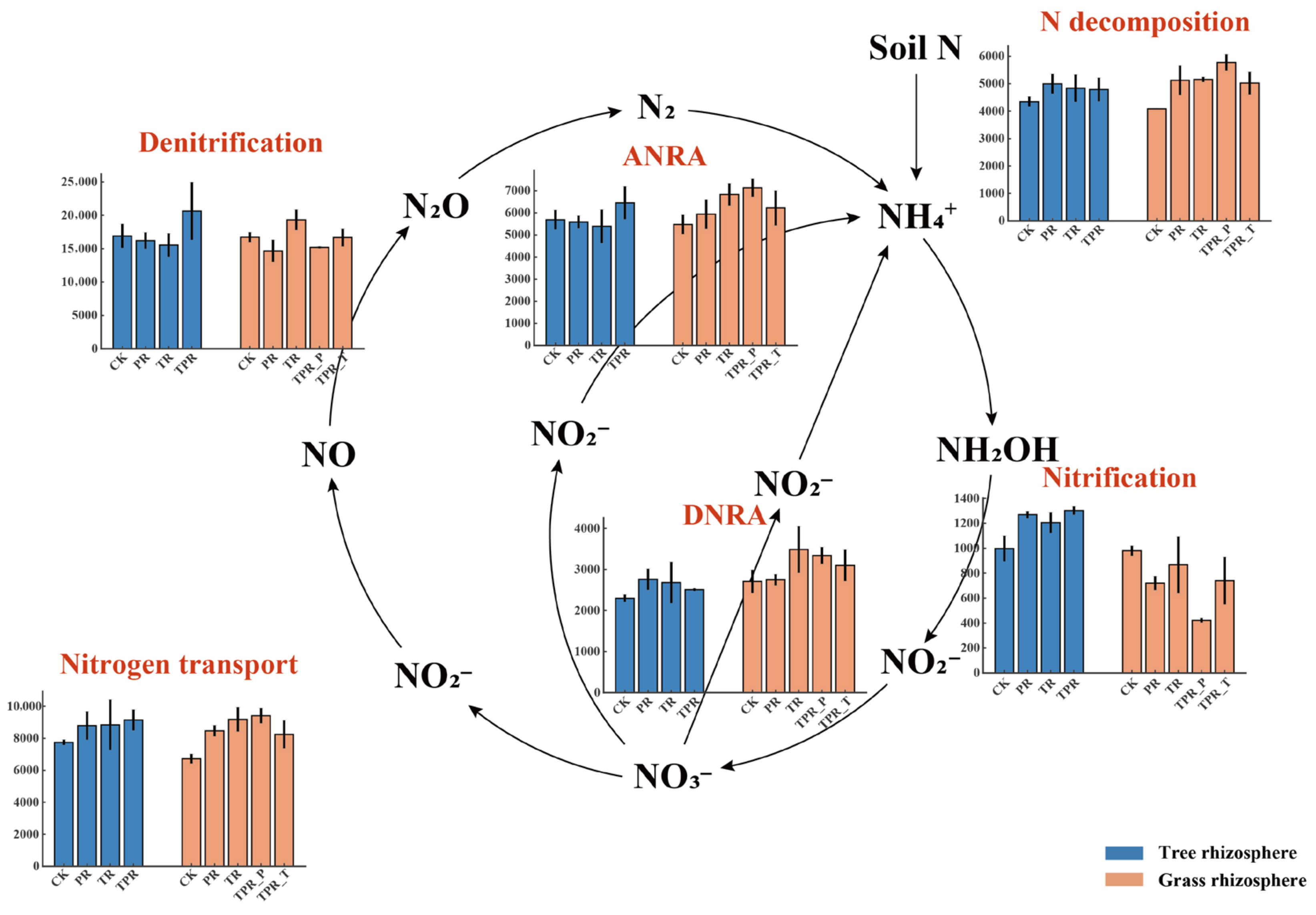

3.2. Responses of Nitrogen-Cycling Microorganisms and Functional Gene Sets to Different Grass Species Configurations in the Peach Orchard

3.3. Key Environmental and Biological Drivers of Soil Nitrogen Availability

4. Discussion

4.1. Regulation of Nitrogen Cycling in Peach Orchards Through Rhizosphere Biochemical Processes Driven by Grass Species Configurationy

4.2. Rhizosphere Microbial Community Restructuring Drives Functional Differentiation of Nitrogen Cycling Under Different Grass Species Configurations

4.3. Synergistic Regulation of Rhizospheric Nitrogen Availability by Environmental and Biological Factors

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, Y.; Chen, H.; Lin, H.; Liu, P.; Song, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, M.; Gao, W.; Song, L. Severe nitrogen leaching and marked decline of nitrogen cycle-related genes during the cultivation of apple orchard on barren mountain. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 367, 108998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiser, T.; Gras, D.E.; Gutiérrez, A.G.; González, B.; Gutiérrez, R.A. A holistic view of nitrogen acquisition in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bascuñán-Godoy, L.; Sanhueza, C.; Hernández, C.E.; Cifuentes, L.; Pinto, K.; Álvarez, R.; González-Teuber, M.; Bravo, L.A. Nitrogen supply affects photosynthesis and photoprotective attributes during drought-induced senescence in quinoa. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Xu, X.; Wanek, W.; Sun, J.; Bardgett, R.D.; Tian, Y.; Cui, X.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Z.; Kuzyakov, Y.; et al. Nitrogen availability in soil controls uptake of different nitrogen forms by plants. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 1450–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulten, H.R.; Schnitzer, M. The chemistry of soil organic nitrogen: A review. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1997, 26, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.E.; Mei, X.; Zhang, W.; Dong, W.; Yan, Z.; Liu, X.; Rachit, S.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Liu, E. Substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic fertilizer affects soil total nitrogen and its fractions in northern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Kong, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Luo, Y.; Wang, G.; Yuan, J. Enhancing the transformation of carbon and nitrogen organics to humus in composting: Biotic and abiotic synergy mediated by mineral material. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 393, 130126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, A.G.; Shrawat, A.K.; Muench, D.G. Can less yield more? Is reducing nutrient input into the environment compatible with maintaining crop production? Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, A.; Hobbie, E.A.; Zhu, F.; Qu, Y.; Dai, L.; Li, D.; Liu, X.; Zhu, W.; Koba, K.; et al. Mature conifers assimilate nitrate as efficiently as ammonium from soils in four forest plantations. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 3184–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Miller, A.J. Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, N.; Wen, X.; Yu, G.; Gao, Y.; Jia, Y. Patterns and regulating mechanisms of soil nitrogen mineralization and temperature sensitivity in Chinese terrestrial ecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 215, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Nesi, A.; Fernie, A.R.; Stitt, M. Metabolic and signaling aspects underpinning the regulation of plant carbon–nitrogen interactions. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 973–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Duan, P.; Wang, K.; Li, D. Topography modulates effects of nitrogen deposition on soil nitrogen transformations by impacting soil properties in a subtropical forest. Geoderma 2023, 432, 116381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.K.; Van den Ende, B. The nitrogen nutrition of the peach tree. IV. Storage and mobilization of nitrogen in mature trees. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1969, 20, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio Ames, Z.; Brecht, J.K.; Olmstead, M.A. Nitrogen fertilization rates in a subtropical peach orchard: Effects on tree vigor and fruit quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J. Effects of early season and autumn nitrogen applications on young ‘Keisie’ canning peach trees on a sandy, infertile soil. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil. 2006, 23, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Zou, J. Fertilizer-induced nitrous oxide emissions from global orchards and its estimate of China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 328, 107854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Pittelkow, C.M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, S. Winter legume-rice rotations can reduce nitrogen pollution and carbon footprint while maintaining net ecosystem economic benefits. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, Y.; Lyu, J. Decomposition of different crop straws and variation in straw-associated microbial communities in a peach orchard, China. J. Arid. Land. 2021, 13, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manici, L.; Caputo, F. Soil fungal communities as indicators for replanting new peach orchards in intensively cultivated areas. Eur. J. Agron. 2010, 33, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, X. Legume Cover with Optimal Nitrogen Management and Nitrification Inhibitor Enhanced Net Ecosystem Economic Benefits of Peach Orchard. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, R.E.; Nelson, N.O.; Roozeboom, K.L.; Kluitenberg, G.J.; Tomlinson, P.J.; Kang, Q.; Abel, D.S. Cover crop and phosphorus fertilizer management impacts on surface water quality from a no-till corn–soybean rotation. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Z.; Peng, C.; Jia, Z.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Y. Leveraging cover crop functional traits and nitrogen synchronization for yield-optimized waxy corn production systems. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1591506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkington, R.; Cahn, M.A.; Vardy, A.; Harper, J.L. The growth, distribution and neighbour relationships of Trifolium repens in a permanent pasture. J. Ecol. 1979, 67, 31–243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pirhofer-Walzl, K.; Rasmussen, J.; Høgh-Jensen, H.; Eriksen, J.; Søegaard, K.; Rasmussen, J. Nitrogen transfer from forage legumes to nine neighbouring plants in a multi-species grassland. Plant Soil 2012, 350, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Smith, K.F.; Cogan, N.O.; Giri, K.; Jacobs, J.L. The genome era of forage selection: Current status and future directions for perennial ryegrass breeding and evaluation. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Nie, G.; Liu, H. Leaf and root growth, carbon and nitrogen contents, and gene expression of perennial ryegrass to different nitrogen supplies. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2016, 141, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.G.; Laidlaw, A.S.; Christie, P.; Hammond, M.E.R. The specificity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in perennial ryegrass–white clover pasture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 77, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Thornton, P.E.; Post, W.M. A global analysis of soil microbial biomass carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013, 22, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zheng, Q.; Noll, L.; Hu, Y.; Wanek, W. Environmental effects on soil microbial nitrogen use efficiency are controlled by allocation of organic nitrogen to microbial growth and regulate gross N mineralization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Ma, L.; Xu, T.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Bai, L. Enhanced nitrification potential soil from a warm-temperate shrub tussock ecosystem under nitrogen deposition and warming is driven by increased Nitrosospira abundance. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, W.; Janda, T.; Molnár, Z. Unveiling the significance of rhizosphere: Implications for plant growth, stress response, and sustainable agriculture. Plant Physiol. Biochem. PPB 2024, 206, 108290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Tang, T.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Neher, D.A.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, J.; Xiao, D.; Hu, P.; Wang, K.; et al. Nitrogen fertilization increases the niche breadth of soil nitrogen-cycling microbes and stabilizes their co-occurrence network in a karst agroecosystem. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 374, 109177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Q.S. Effects of soil tillage and planting grass on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal propagules and soil properties in citrus orchards in southeast China. Soil. Tillage Res. 2016, 155, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, R.; Xing, F. Planting grass enhances relations between soil microbes and enzyme activities and restores soil functions in a degraded grassland. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1290849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aban, C.L.; Larama, G.; Ducci, A.; Huidobro, J.; Sabate, D.C.; Gil, S.V.; Brandan, C.P. Restoration of degraded soils with perennial pastures shifts soil microbial communities and enhances soil structure. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 382, 109472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, G.; Chen, C.; Lu, A. Effects of Different Sod-Seeding Patterns on Soil Properties, Nitrogen Cycle Genes, and N2O Mitigation in Peach Orchards. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Decraemer, W. First Report of the Dagger Nematode Xiphinema dentatum (Nematoda: Longidoridae) in a Deciduous Forest in the Czech Republic. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placidi, P.; Vergini, C.; Papini, N.; Cecconi, M.; Mezzanotte, P.; Scorzoni, A. Low-Cost and Low-Frequency Impedance Meter for Soil Water Content Measurement in the Precision Agriculture Scenario. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 9511613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, W.; Yang, W. Improvements in soil health and soil carbon sequestration by an agroforestry for food production system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 333, 107945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, S.; Zhou, H.; Ji, J. Methods for reducing the tillage force of subsoiling tools: A review. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 229, 105676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Sheng, H.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Z. Land use conversion and lithology impacts soil aggregate stability in subtropical China. Geoderma 2021, 389, 114953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Sallach, J.B.; Hodson, M.E. Size- and concentration-dependent effects of microplastics on soil aggregate formation and properties. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Gao, W.; Yuan, H.; Kuzyakov, Y.; et al. Stoichiometric regulation of priming effects and soil carbon balance by microbial life strategies. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2022, 169, 108669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; McCormack, M.L.; Suseela, V.; Kennedy, P.G.; Tharayil, N. Formations of mycorrhizal symbiosis alter the phenolic heteropolymers in roots and leaves of four temperate woody species. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Du, L.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Gaafar, A.; Zhang, P.; Cai, T.; Liu, T.; Jia, Z.; et al. Appropriate fertilization increases carbon and nitrogen sequestration and economic benefit for straw-incorporated upland farming. Geoderma 2024, 441, 116743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, M.C.; Oliveira, K.A.; de Fátima, Â.; Coltro, W.K.T.; Santos, J.C.C. Paper-based analytical device with colorimetric detection for urease activity determination in soils and evaluation of potential inhibitors. Talanta 2021, 230, 122301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.D.; Sobral, D.; Pinheiro, M.; Isidro, J.; Bogaardt, C.; Pinto, M.; Eusébio, R.; Santos, A.; Mamede, R.; Horton, D.L.; et al. INSaFLU-TELEVIR: An open web-based bioinformatics suite for viral metagenomic detection and routine genomic surveillance. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Muriel, J.; Tyndale, S.; D’Angelo, J.; Sánchez, P.; Shah, P.; Huang, Y.; Miller, J.; Niemeijer, M. A Tumor-Only Whole Genome Sequencing Pipeline for the Development of Molecular Pathology Assays for AML. Blood 2024, 144, 7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, Q.; Fan, G.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Nie, J.; Ma, J.; Wu, L. gcMeta 2025: A global repository of metagenome-assembled genomes enabling cross-ecosystem microbial discovery and function research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, gkaf1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassignani, A.; Plancade, S.; Berland, M.; Blein-Nicolas, M.; Guillot, A.; Chevret, D.; Moritz, C.; Huet, S.; Rizkalla, S.; Clément, K.; et al. Taxonomic and functional annotations of the Integrated non-redundant Gene Catalog 9.9. Zenodo 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chun, Y.; Grishina, G.; Lo, T.; Reed, K.; Wang, J.; Sicherer, S.; Berin, M.C.; Bunyavanich, S. Oral and Gut Microbial Hubs Associated with Reaction Threshold Interact with Circulating Immune Factors in Peanut Allergy. Allergy 2025, 80, 2800–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Peng, Y.; Guo, F.; Zhang, F.; Yin, Z.; Li, F. Mechanistic Multitrophic Insight on Seasonal Hypoxia Impacts in Urbanized Estuarine Ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 21657–21669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Hou, R.; Fu, Q.; Li, T.; Li, M.; Dong, S.; Shi, G. Soil environment, carbon and nitrogen cycle functional genes in response to freeze-thaw cycles and biochar. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 141345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Evans, S.E.; Friesen, M.L.; Tiemann, L.K. Root exudates shift how N mineralization and N fixation contribute to the plant-available N supply in low fertility soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 165, 108541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Chang, S.X.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Niu, S.; Hu, S. Nitrogen deposition differentially affects soil gross nitrogen transformations in organic and mineral horizons. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 201, 103033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Li, Z.; Niu, S. Global soil gross nitrogen transformation under increasing nitrogen deposition. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2021, 35, e2020GB006711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, C.; Piquette, J.; Dussault-Chouinard, É.; Morin, H.; Thiffault, N.; Houle, D.; Bradley, R.L.; Ouimet, R.; Simpson, M.J.; Paré, M.C. Canopy nitrogen addition and soil warming affect conifer seedlings’ phenology but have limited impact on growth and soil N mineralization in boreal forests of Eastern Canada. Front. For. Glob. Change 2020, 3, 581363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sang, C.; Yang, J.; Qu, L.; Xia, Z.; Sun, H.; Jiang, P.; Wang, X.; He, H.; Wang, C. Stoichiometric imbalance and microbial community regulate microbial element use efficiencies under nitrogen addition. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2021, 156, 108207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, R.; Ghoshal Chaudhuri, S.; Sheeja, T.E.; Shiva, K.N. Soil microbial activity and biomass is stimulated by leguminous cover crops. J. Plant Nutr. Soil. Sci. 2009, 172, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooch, Y.; Ehsani, S.; Akbarinia, M. Stoichiometry of microbial indicators shows clearly more soil responses to land cover changes than absolute microbial activities. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 131, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberger, W.T., Jr.; Dick, W.A. Relationships between enzyme activities and microbial growth and activity indices in soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1983, 47, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, H.L.; Hausinger, R.P. Microbial ureases: Significance, regulation, and molecular characterization. Microbiol. Rev. 1989, 53, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juturu, V.; Wu, J.C. Microbial cellulases: Engineering, production and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 33, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, G. Effects of green manure continuous application on soil microbial biomass and enzyme activity. J. Plant Nutr. 2014, 37, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, R. Enzymatic degradation of cellulose in soil: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Hui, D.; Vancov, T.; Fang, Y.; Tang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Ge, T.; Cai, Y.; Yu, B.; et al. Pyrogenic organic matter decreases while fresh organic matter increases soil heterotrophic respiration through modifying microbial activity in a subtropical forest. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2024, 60, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, Q.; Reitz, T.; Schädler, M.; Hodgskiss, L.H.; Peng, J.; Schnabel, B.; Buscot, F.; Eisenhauer, N.; Schleper, C.; Heintz-Buschart, A. Metabolic potential of Nitrososphaera-associated clades. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Qian, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Luo, X. Nitrifier community assembly and species co-existence in forest and meadow soils across four sites in a temperate to tropical region. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2022, 171, 104342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, H.; Gong, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L. Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) and nrfA gene in crop soils: A meta-analysis of cropland management effects. GCB Bioenergy 2025, 17, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Tang, S.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, T.; Ma, X. Root exudates contribute to belowground ecosystem hotspots: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 937940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghaï, A.; Moore, O.C.; Jones, C.M.; Hallin, S. Microbial controls of nitrogen retention and N2O production in crop systems supporting soil carbon accrual. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 208, 109858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Van Groenigen, K.J.; Hungate, B.A.; Cao, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, R.W. A keystone microbial enzyme for nitrogen control of soil carbon storage. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaaq1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, S.; Li, J.; Chen, J.I.; Wang, G.; Mayes, M.A.; Dzantor, K.E.; Hui, D.; Luo, Y. Soil extracellular enzyme activities, soil carbon and nitrogen storage under nitrogen fertilization: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 101, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Microbial enzyme-catalyzed processes in soils and their analysis. Plant Soil. Environ. 2009, 55, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, M.; Alexandre, A.; Oliveira, S. Legume growth-promoting rhizobia: An overview on the Mesorhizobium genus. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, L.J.; Nicol, G.W.; Smith, Z.; Fear, J.; Prosser, J.I.; Baggs, E.M. Nitrosospira spp. can produce nitrous oxide via a nitrifier denitrification pathway. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, L.H.; Rodriguez-R, L.M.; Higgins, S.; Chee-Sanford, J.C.; Sanford, R.A.; Ritalahti, K.M.; Löffler, F.E.; Konstantinidis, K.T. Detecting nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ) genes in soil metagenomes: Method development and implications for the nitrogen cycle. mBio 2014, 5, e01048-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Heo, H.; Han, H.; Song, D.U.; Bakken, L.R.; Frostegård, Å.; Yoon, S. Suggested role of NosZ in preventing N2O inhibition of dissimilatory nitrite reduction to ammonium. mBio 2023, 14, e01540-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modes | CK | TPr | Tr | Pr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | clean tillage | Trifolium repens and Lolium perenne mixed sowing | Trifolium repens monoculture | Lolium perenne monoculture |

| Seed amounts | 0 kg·667 m−2 | 0.5 and 1 kg·667 m−2 | 1 kg·667 m−2 | 2 kg·667 m−2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, Z.; Guo, J.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, G.; Lu, A.; Shao, X.; Kan, H. Inter-Row Grassing Reshapes Nitrogen Cycling in Peach Orchards by Influencing Microbial Pathways in the Rhizosphere. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2770. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122770

Pang Z, Guo J, Xu H, Li Y, Chen C, Zhang G, Lu A, Shao X, Kan H. Inter-Row Grassing Reshapes Nitrogen Cycling in Peach Orchards by Influencing Microbial Pathways in the Rhizosphere. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2770. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122770

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Zhuo, Jiale Guo, Hengkang Xu, Yufeng Li, Chao Chen, Guofang Zhang, Anxiang Lu, Xinqing Shao, and Haiming Kan. 2025. "Inter-Row Grassing Reshapes Nitrogen Cycling in Peach Orchards by Influencing Microbial Pathways in the Rhizosphere" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2770. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122770

APA StylePang, Z., Guo, J., Xu, H., Li, Y., Chen, C., Zhang, G., Lu, A., Shao, X., & Kan, H. (2025). Inter-Row Grassing Reshapes Nitrogen Cycling in Peach Orchards by Influencing Microbial Pathways in the Rhizosphere. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2770. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122770