Species Identification, Virulence Factors, and Antifungal Resistance in Clinical Candida Isolates from ICU Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeasts and Growth Conditions

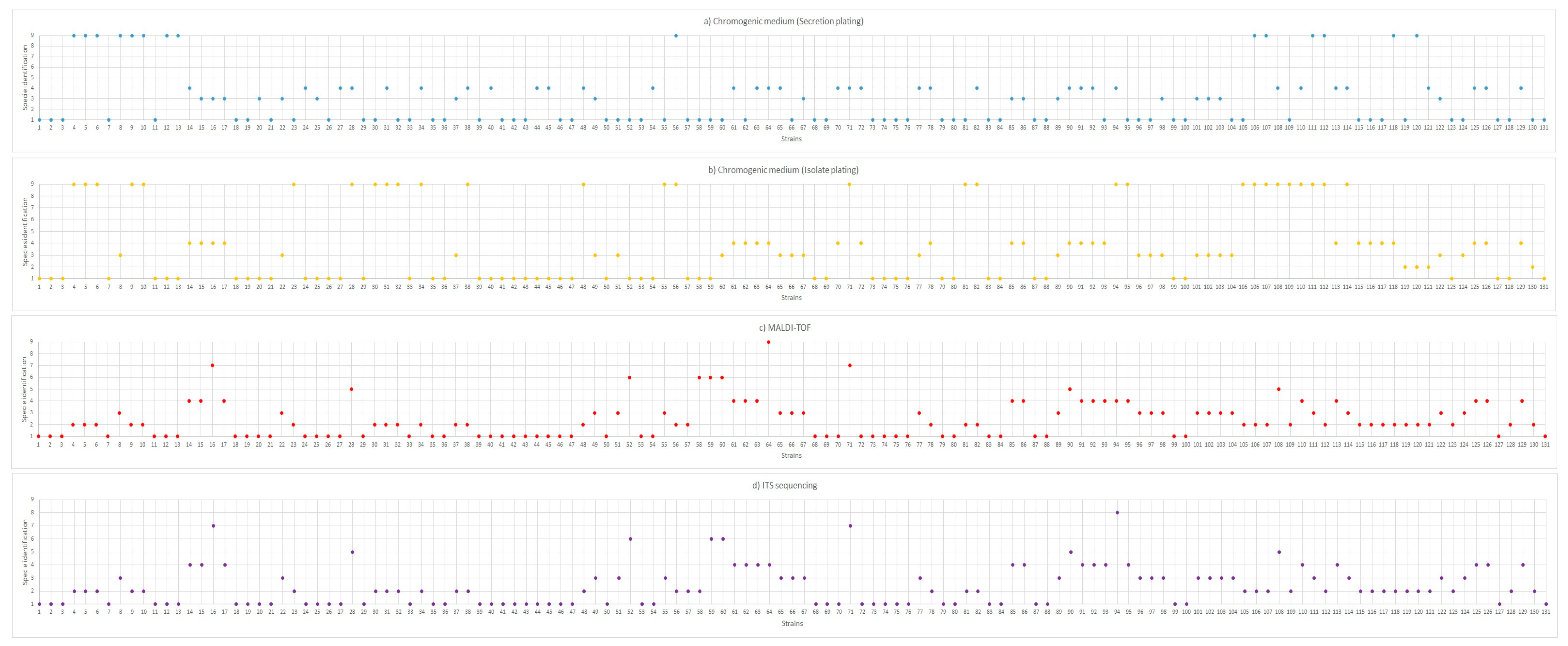

2.2. Phenotypic Identification of Candida spp. Using Chromogenic Culture Medium

2.3. Candida spp. Identification by MALDI-TOF Analysis

2.4. Candida spp. Identification by ITS Sequencing

2.5. Antifungal Sensitivity of Candida Isolates

2.6. Esterase Production

2.7. DNase Production

2.8. Protease Production

2.9. Hemolytic Activity

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

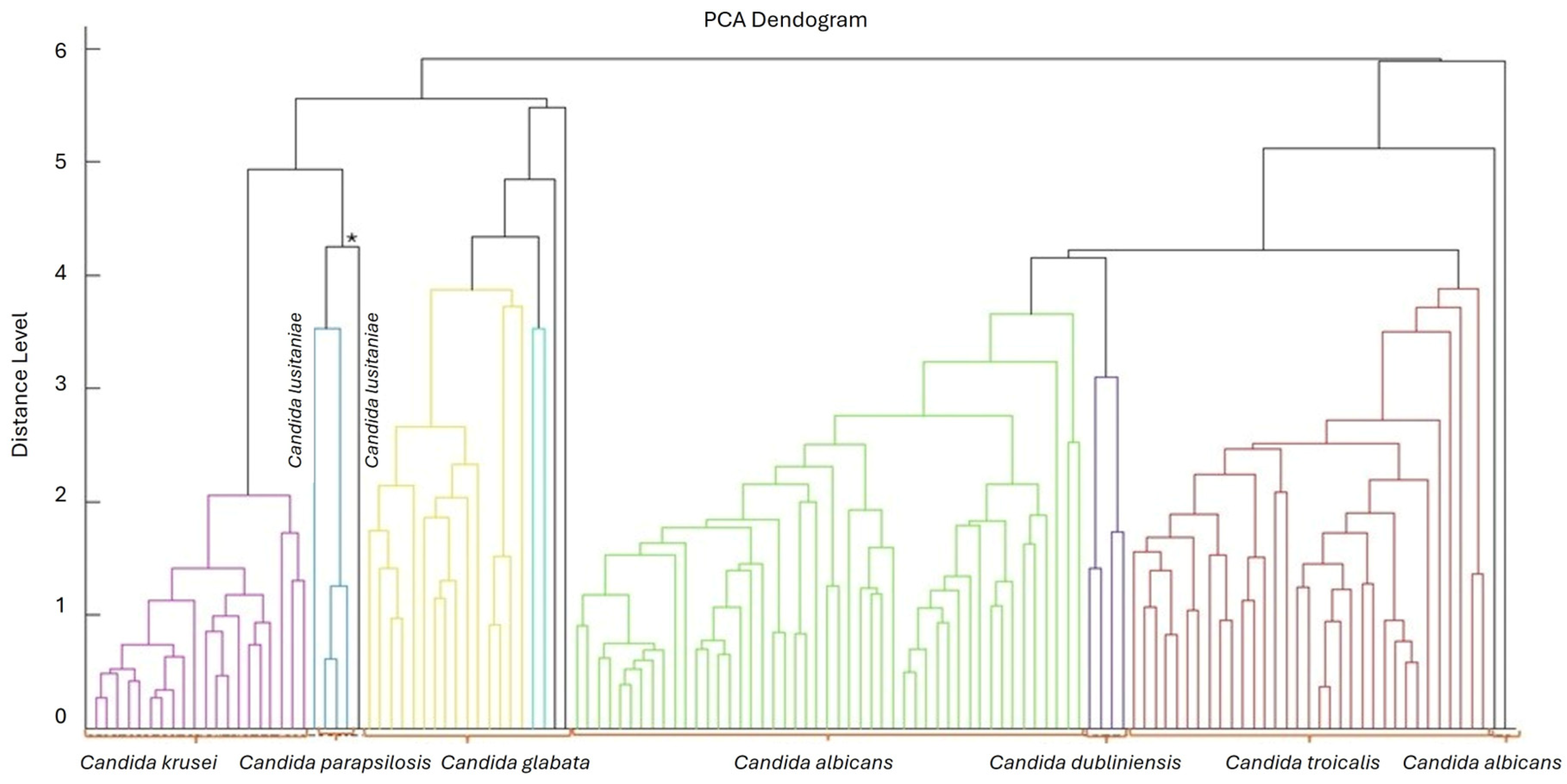

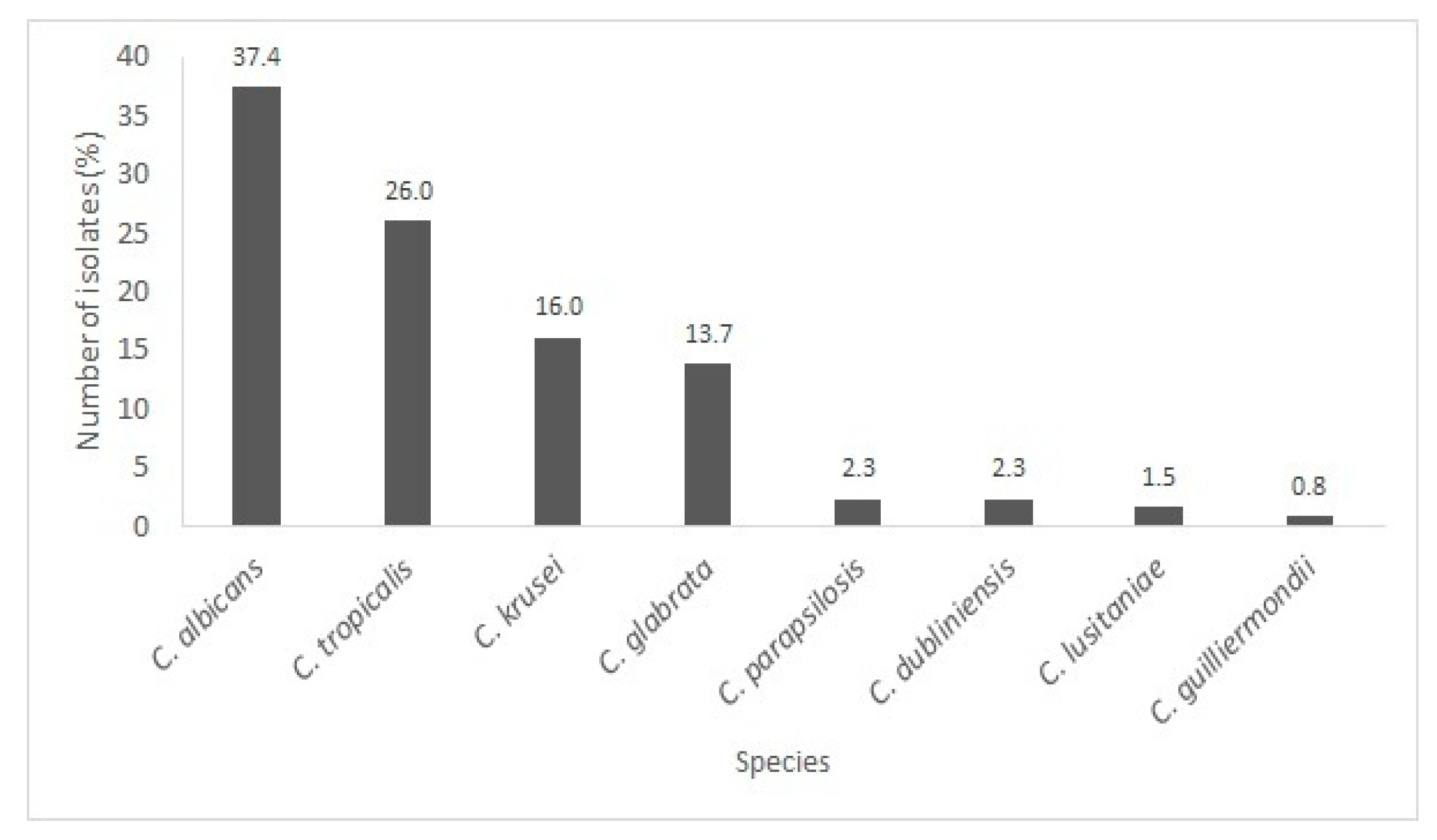

3.1. Yeast Identification

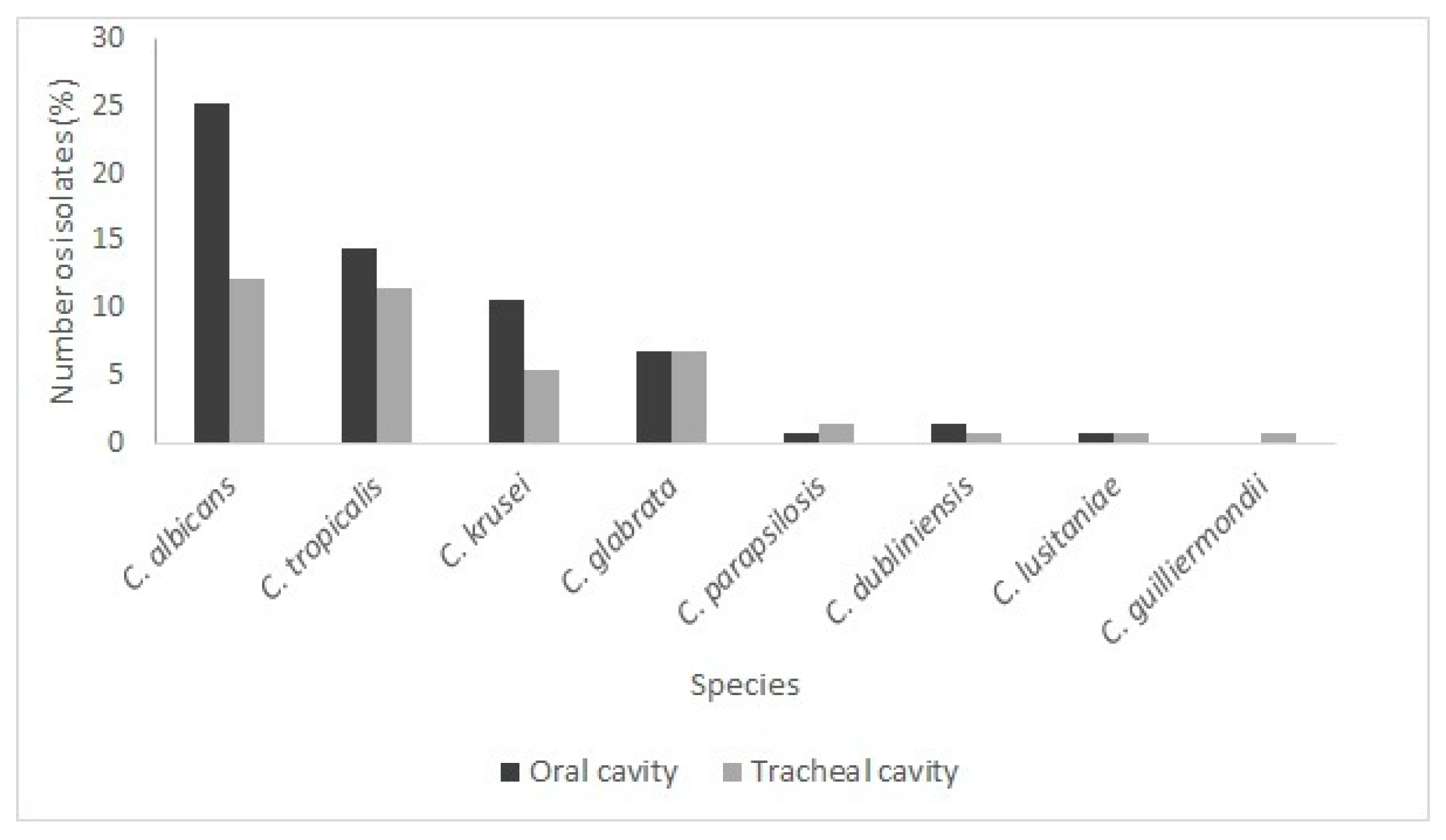

Species Present in the Oral and Tracheal Cavities

3.2. Antifungal Resistance

3.3. Virulence Factors

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations of the Study and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J.; Turnidge, J.D.; Castanheira, M.; Jones, R.N. Twenty years of the SENTRY antifungal surveillance program: Results for Candida species from 1997–2016. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, S79–S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staniszewska, M. Virulence factors in Candida species. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2020, 21, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musinguzi, B.; Akampurira, A.; Derick, H.; Mwesigwa, A.; Mwebesa, E.; Mwesigye, V.; Kabajulizi, I.; Sekulima, T.; Ocheng, F.; Itabangi, H.; et al. Extracellular hydrolytic enzyme activities and biofilm formation in Candida species isolated from people living with human immunodeficiency virus with oropharyngeal candidiasis at HIV/AIDS clinics in Uganda. Microb. Pathog. 2025, 199, 107232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Sun, L.; Gounder, A.P.; Watanabe, M.; Marrero, L.; Kobayashi, H.; Ainslie, K.M.; Brown, G.D.; Wong, M.H.; Underhill, D.M.; et al. Structural specificities of cell surface β-glucan polysaccharides determine commensal yeast–mediated immunomodulatory activities. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimowicz, M.; Bucka-Kolendo, J. MALDI-TOF MS—Application in food microbiology. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2020, 67, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, S.R.; Lyman, M.M.; Sexton, D.J. Tools for Detecting a “Superbug”: Updates on Candida auris Testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e00808-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, P.H.d.C.; Moura, C.R.F.; Lage, V.K.S.; Teixeira, L.A.C.; Costa, H.S.; Figueiredo, P.H.S.; Santos, J.N.V.; de Jesus, P.H.C.; Freitas, D.A.; Lacerda, A.C.R.; et al. Factors associated with the presence of Candida spp. in oral and tracheobronchial secretions of adult intensive care unit patients. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 111, 116687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, D.S.; Teniola, O.D.; Ban-Koffi, L.; Owusu, M.; Andersson, T.S.; Holzapfel, W.H. The microbiology of Ghanaian cocoa fermentations analysed using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 114, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Method for Antifungal Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; CLSI Guideline M44, 3rd ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-68440-031-7. [Google Scholar]

- Galán-Ladero, M.A.; Blanco, M.T.; Sacristán, B.; Fernández-Calderón, M.C.; Pérez-Giraldo, C.; Gómez-García, A.C. Enzymatic activities of Candida tropicalis isolated from hospitalized patients. Med. Mycol. 2010, 48, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riceto, É.B.d.M.; Menezes, R.P.; Penatti, M.P.A.; Pedroso, R.d.S. Enzymatic and hemolytic activity in different Candida species. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2015, 32, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staib, F. Serum proteins as a nitrogen source for yeast-like fungi. Sabouraudia 1966, 4, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rörig, K.C.O.; Colacite, J.; Abegg, M.A. Production of virulence factors in vitro by pathogenic species of the genus Candida. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2009, 42, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulimane, S.; Maluvadi-Krishnappa, R.; Mulki, S.; Rai, H.; Dayakar, A.; Kabbinahalli, M. Speciation of Candida using CHROMagar in cases with oral epithelial dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e657–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odds, F.C.; Bernaerts, R. CHROMagar Candida, a new differential isolation medium for presumptive identification of clinically important Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1994, 32, 1923–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Houston, A.; Coffmann, S. Application of CHROMagar Candida for rapid screening of clinical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Salazar, E.; Betancourt-Cisneros, P.; Ramírez-Magaña, X.; Díaz-Huerta, H.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Frías-De-León, M.G. Utility of Cand PCR in the diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis in pregnant women. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menu, E.; Criscuolo, A.; Desnos-Ollivier, M.; Cassagne, C.; D’Incan, E.; Furst, S.; Ranque, S.; Berger, P.; Dromer, F. Outbreak of Saprochaete clavata Infecting a Cancer Center Through a Dish-Washing Machine. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2031–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parambath, S.; Dao, A.; Kim, H.Y.; Zawahir, S.; Izquierdo, A.A.; Tacconelli, E.; Govender, N.; Oladele, R.; Colombo, A.; Sorrell, T.; et al. Candida albicans—A systematic review to inform the World Health Organization Fungal Priority Pathogens List. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae045, Erratum in Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbedo, L.S.; Sgarbi, D.B.G. Candidiasis. J. Bras. Doenças Sex. Transm. 2010, 22, 22–38. Available online: https://bdst.emnuvens.com.br/revista/article/view/1070 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Lohse, M.B.; Gulati, M.; Johnson, A.D.; Nobile, C.J. Development and regulation of single- and multi-species Candida albicans biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortorano, A.M.; Prigitano, A.; Morroni, G.; Brescini, L.; Barchiesi, F. Candidemia: Evolution of drug resistance and novel therapeutic approaches. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 5543–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J.; Gibbs, D.L.; Newell, V.A.; Ellis, D.; Tullio, V.; Rodloff, A.; Fu, W.; Ling, T.A. The Global Antifungal Surveillance Group. Results from the ARTEMIS DISK Global Antifungal Surveillance Study, 1997–2007: A 10.5-year analysis of susceptibilities of Candida species to fluconazole and voriconazole as determined by CLSI standardized disk diffusion. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 1366–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, P.G.V.; Menezes, R.P.; Silva, N.B.S.; Faria, G.O.; Bessa, M.A.S.; Araújo, L.B.; Aguiar, P.A.D.F.; Penatti, M.P.A.; Pedroso, R.d.S.; Röder, D.v.D.B. Virulence factors, antifungal susceptibility and molecular profile in Candida species isolated from the hands of health professionals before and after cleaning with 70% ethyl alcohol–based gel. J. Mycol. Med. 2024, 34, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.P.; Lionakis, M.S. Pathogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. Virulence 2022, 13, 89–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Li, L.; Yan, Z. Candida albicans overgrowth disrupts the gut microbiota in mice bearing oral cancer. Mycology 2023, 15, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govrins, M.; Lass-Flörl, C. Candida parapsilosis complex in the clinical setting. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, J.W.; Bayless, D.R.; Ranganath, N.; Stevens, R.W.; Kind, D.R.; Wengenack, N.L.; Shah, A.S. Candida guilliermondii fungemia: A 12-year retrospective review of antimicrobial susceptibility patterns at a reference laboratory and tertiary care center. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e0105724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, Y.P.; Bastos, L.Q.D.A.; Bastos, V.Q.D.A.; Bastos, R.V.; Bastos, Y.S.; Bastos, A.N.; Machado, A.B.F.; Watanabe, A.A.S.; Diniz, C.G.; Silva, V.L.; et al. Epidemiologia das infecções por Candida spp. em pacientes comunitários e hospitalizados em Juiz de Fora, MG. In Doenças Infecciosas e Parasitárias, 8th ed.; Chapter 22; Pasteur: Irati, Brazil, 2024; pp. 177–186. ISBN 978-65-6029-048-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloi, M.; Lenetha, G.G.; Malebo, N.J. Microbial levels on street foods and food preparation surfaces in Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality. Health SA Gesondheid 2021, 26, a1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.L.; Lima, M.E.; dos Santos, R.D.T.; Lima, E.O. Onychomycoses due to fungi of the genus Candida: A literature review. Res. Soc. Dev. 2020, 9, e560985771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamaletsou, M.N.; Rammaert, B.; Bueno, M.A.; Sipsas, N.V.; Moriyama, B.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Roilides, E.; Zeller, V.; Taj Aldeen, S.J.; Miller, A.O.; et al. Candida arthritis: Analysis of 112 pediatric and adult cases. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2015, 3, ofv207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, L. Ketoconazole induces reversible antifungal drug tolerance mediated by trisomy of chromosome R in Candida albicans. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1450557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masala, L.; Luzzati, R.; Maccacaro, L.; Antozzi, L.; Concia, E.; Fontana, R. Nosocomial cluster of Candida guilliermondii fungemia in surgical patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2003, 22, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, J.D.; Rosengard, B.R.; Merz, W.G.; Stuart, R.K.; Hutchins, G.M.; Saral, R. Fatal disseminated candidiasis due to amphotericin B–resistant Candida guilliermondii. Ann. Intern. Med. 1985, 102, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, C.J.; Rajan, S.; Wong, S.S.; Tsang, D.N.; Lai, C.K.; Samaranayake, L.P.; Jin, L. Antifungal susceptibility in serum and virulence determinants of Candida bloodstream isolates from Hong Kong. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savastano, C.; Silva, E.O.; Gonçalves, L.L.; Nery, J.M.; Silva, N.C.; Dias, A.L. Candida glabrata among Candida spp. from environmental health practitioners of a Brazilian hospital. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2016, 47, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paula Menezes, R.; de Melo Riceto, É.B.; Borges, A.S.; de Brito Röder, D.V.D.; dos Santos Pedroso, R. Evaluation of virulence factors of Candida albicans isolated from HIV-positive individuals using HAART. Arch. Oral Biol. 2016, 66, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellepola, A.N.B.; Chandy, R.; Khan, Z.U. Post-antifungal effect and adhesion to buccal epithelial cells of oral Candida dubliniensis isolates subsequent to limited exposure to amphotericin B, ketoconazole and fluconazole. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2015, 6, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.H.; Astvad, K.M.T.; Silva, L.V.; Sanglard, D.; Jørgensen, R.; Nielsen, K.F.; Mathiasen, E.G.; Doroudian, G.; Perlin, D.S.; Arendrup, M.C. Stepwise emergence of azole, echinocandin and amphotericin B multidrug resistance in vivo in Candida albicans orchestrated by multiple genetic alterations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2551–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Hawkins, N.J.; Sanglard, D.; Gurr, S.J. Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance in Candida spp. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortegiani, A.; Misseri, G.; Chowdhary, A. What’s new on emerging resistant Candida species. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, M.; Barreiros, G.; Guimarães, L.F.; Deriquehem, V.A.S.; Castiñeiras, A.C.; Nouér, S.A. Increased incidence of candidemia in a tertiary care hospital with the COVID-19 pandemic. Mycoses 2021, 64, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arastehfar, A.; Daneshnia, F.; Hilmioğlu-Polat, S.; Fang, W.; Yaşar, M.; Polat, F.; Metin, D.Y.; Rigole, P.; Coenye, T.; Ilkit, M.; et al. First Report of Candidemia Clonal Outbreak Caused by Emerging Fluconazole-Resistant Candida parapsilosis Isolates Harboring Y132F and/or Y132F+K143R in Turkey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01001-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Guinea, J.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Meijer, E.F.J.; Meis, J.F.; Buil, J.B.; Dannaoui, E.; Giske, C.G.; Lyskova, P.; Meletiadis, J. How to interpret MICs of amphotericin B, echinocandins and flucytosine against Candida auris (Candidozyma auris) according to the newly established European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) breakpoints. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2026, 32, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L.S.; Branquinha, M.H.; Santos, A.L.S. Different classes of hydrolytic enzymes produced by multidrug-resistant yeasts comprising the Candida haemulonii complex. Med. Mycol. 2017, 55, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo-Carvalho, M.H.G.; Silva, R.T.; Souza, A.A.; Oliveira, J.A.; Silva, T.A.; Pereira, M.D.; Santos, L.M.; Almeida, M.F.; Lima, A.P.; Costa, A.L.; et al. Relationship between the antifungal susceptibility profile and the production of virulence-related hydrolytic enzymes in Brazilian clinical strains of Candida glabrata. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 8952878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouraei, H.; Ghaderian Jahromi, M.; Razeghian Jahromi, L.; Zomorodian, K.; Pakshir, K. Potential pathogenicity of Candida species isolated from oral cavity of patients with diabetes mellitus. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9982744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaiarasan, K.; Singh, R.; Chaturvedula, L. Changing virulence factors among vaginal non-albicans Candida species. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 36, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, J.C.; Vilela, S.F.G.; Rossoni, R.D.; Barbosa, J.O.; Costa, A.C.B.P.; Rasteiro, V.M.C.; Suleiman, J.M.A.H.; Jorge, A.O.C. Oral colonization by yeasts in HIV-positive patients in Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2012, 54, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makled, A.F.; Ali, S.A.M.; Labeeb, A.Z.; El-Sayed, M.A.; Hassan, Z.K.; Abdel-Hakim, A.; Ahmed, A.M.; Sabal, M.S. Characterization of Candida species isolated from clinical specimens: Insights into virulence traits, antifungal resistance and molecular profiles. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, İ.; Aydın, F.; Kaklıkaya, N.; Ertürk, M. Induction of secretory aspartyl proteinase of Candida albicans by HIV-1 but not HSV-2 or some other microorganisms associated with vaginal environment. Mycopathologia 2005, 159, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossoni, R.D.; Barbosa, J.O.; Vilela, S.F.G.; Jorge, A.O.C.; Junqueira, J.C. Comparison of the hemolytic activity between Candida albicans and non-albicans Candida species. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2013, 27, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlaneto, M.C.; Góes, H.P.; Perini, H.F.; dos Santos, R.C.; Furlaneto-Maia, L. How much do we know about hemolytic capability of pathogenic Candida species? Folia Microbiol. 2018, 63, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsipoulaki, M.; Stappers, M.H.T.; Malavia-Jones, D.; Brunke, S.; Hube, B.; Gow, N.A.R. Candida albicans and Candida glabrata: Global priority pathogens. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2024, 88, e00021-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajni, E.; Chaudhary, P.; Garg, V.K.; Sharma, R.; Malik, M. A complete clinico-epidemiological and microbiological profile of candidemia cases in a tertiary-care hospital in Western India. Antimicrob. Steward Healthc. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siikala, E.; Richardson, M.; Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J.; Messer, S.A.; Perheentupa, J.; Saxén, H.; Rautemaa, R. Candida albicans isolates from APECED patients show decreased susceptibility to miconazole. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2009, 34, 606–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.Q.; Magalhães, J.C.S. Profile of resistance of opportunistic mycosis agents in Brazil. InterAm. J. Med. Health 2021, 4, e202101010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabl, J.T.; Sandini, S.; Stärkel, P.; Hartmann, P. Serum Levels of Candida albicans 65-kDa Mannoprotein (CaMp65p) Correlate with Liver Disease in Patients with Alcohol Use Disorder. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, K.T. Probiotic-Fermented Foods and Antimicrobial Stewardship: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Translational Pathways Against AMR. Fermentation 2025, 11, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasani, E.; Yadegari, M.H.; Khodavaisy, S.; Rezaie, S.; Salehi, M.; Getso, M.I. Virulence factors and azole-resistant mechanism of Candida tropicalis isolated from candidemia. Mycopathologia 2021, 186, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, K.T.; da Silva, R.N.A.; Borges, A.S.; Siqueira, A.E.B.; Puerari, C.; Bento, J.A.C. Smart and Functional Probiotic Microorganisms: Emerging Roles in Health-Oriented Fermentation. Fermentation 2025, 11, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Fang, Z.; Wang, F.; Luo, J.; Yan, L. Effects of Cinnamon Essential Oil on Intestinal Flora Regulation of Ulcerative Colitis Mice Colonized by Candida albicans. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Antifungal Resistance * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole | Ketoconazole | Amphotericin B | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Oral Cavity | ||||||

| C. albicans | 21 | 50.0 | 26 | 74.3 | 08 | 53.3 |

| C. tropicalis | 07 | 16.7 | 03 | 8.6 | 03 | 20.0 |

| C. krusei | 11 | 26.2 | 04 | 11.4 | 02 | 13.3 |

| C. glabrata | 03 | 7.1 | 02 | 5.7 | 01 | 6.7 |

| C. parapsilosis | - | - | - | - | 01 | 6.7 |

| C. dubliniensis | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | - | - |

| C. lusitaniae | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C. guilliermondii | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 |

| Total | 42 | 32.1 ** | 35 | 26.6 ** | 15 | 11.5 ** |

| Tracheal Cavity | ||||||

| C. albicans | 07 | 28.0 | 09 | 42.9 | 02 | 20.0 |

| C. tropicalis | 06 | 24.0 | 04 | 19.0 | 03 | 30.0 |

| C. krusei | 06 | 24.0 | 04 | 19.0 | 03 | 30.0 |

| C. glabrata | 04 | 16.0 | 02 | 9.5 | 01 | 10.0 |

| C. parapsilosis | - | - | - | - | 00 | 00 |

| C. dubliniensis | 01 | 4.0 | 01 | 4.8 | - | - |

| C. lusitaniae | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C. guilliermondii | 01 | 4.0 | 01 | 4.8 | 01 | 10.0 |

| Total | 25 | 19.1 ** | 21 | 16 ** | 10 | 7.7 ** |

| Species | Virulence Factors * | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esterase | DNase | Protease | Hemolytic Activity | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| C. albicans | 39 | 45.8 | 04 | 16.7 | 21 | 35.0 | 37 | 42.0 |

| C.tropicalis | 30 | 35.3 | 06 | 25.0 | 15 | 25.0 | 24 | 27.7 |

| C. krusei | 09 | 10.6 | 08 | 33.3 | 10 | 16.7 | 12 | 13.6 |

| C. glabrata | 06 | 7.1 | 03 | 12.5 | 08 | 13.3 | 07 | 8.0 |

| C. parapsilosis | - | - | 01 | 4.2 | 01 | 1.7 | 03 | 3.4 |

| C. dubliniensis | - | - | 02 | 8.3 | 03 | 5.0 | 03 | 3.4 |

| C. lusitaniae | - | - | - | - | 01 | 1.7 | 02 | 2.3 |

| C. guilliermondii | 01 | 1.2 | - | - | 01 | 1.7 | - | - |

| Total | 85 | 64.9 ** | 24 | 18.3 ** | 60 | 45.8 ** | 88 | 67.2 ** |

| Species | Virulence Factors * | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esterase | DNase | Protease | Hemolytic Activity | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Oral cavity | ||||||||

| C. albicans | 27 | 51.9 | 03 | 33.3 | 14 | 34.1 | 26 | 48.1 |

| C.tropicalis | 17 | 32.7 | 00 | 00 | 12 | 29.3 | 14 | 25.9 |

| C. krusei | 05 | 9.6 | 05 | 55.6 | 08 | 19.5 | 07 | 13.0 |

| C. glabrata | 03 | 5.8 | 00 | 00 | 05 | 12.2 | 03 | 5.5 |

| C. parapsilosis | - | - | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 01 | 1.9 |

| C. dubliniensis | - | - | 01 | 11.1 | 02 | 4.9 | 02 | 3.7 |

| C. lusitaniae | - | - | - | - | 00 | 00 | 01 | 1.9 |

| C. guilliermondii | 00 | 00 | - | - | 00 | 00 | - | - |

| Total | 52 | 39.7 ** | 09 | 6.9 ** | 41 | 31.3 ** | 54 | 41.2 ** |

| Tracheal cavity | ||||||||

| C. albicans | 12 | 36.4 | 01 | 6.6 | 07 | 36.8 | 11 | 32.4 |

| C.tropicalis | 13 | 39.4 | 06 | 40.0 | 03 | 15.8 | 10 | 29.4 |

| C. krusei | 04 | 12.1 | 03 | 20.0 | 02 | 10.4 | 05 | 14.7 |

| C. glabrata | 03 | 9.1 | 03 | 20.0 | 03 | 15.8 | 04 | 11.8 |

| C. parapsilosis | - | - | 01 | 6.7 | 01 | 5.3 | 02 | 5.9 |

| C. dubliniensis | - | - | 01 | 6.7 | 01 | 5.3 | 01 | 2.9 |

| C. lusitaniae | - | - | - | - | 01 | 5.3 | 01 | 2.9 |

| C. guilliermondii | 01 | 3.0 | - | - | 01 | 5.3 | - | - |

| Total | 33 | 25.2 ** | 15 | 11.4 ** | 19 | 14.5 ** | 34 | 26.0 ** |

| C. albicans | C. non-albicans | OR (95% CI) | p Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole resistance | 28/49 (57.1) | 39/82 (47.6) | 1.47 (0.72–3.00) | 0.29 |

| Ketoconazole resistance | 35/49 (71.4) | 21/82 (25.6) | 7.26 (3.28–16.06) | 0.00 |

| Amphotericin B resistance | 10/49 (20.4) | 15/82 (18.3) | 1.14 (0.47–2.77) | 0.77 |

| Esterase activity | 39/49 (79.6) | 46/82 (56.1) | 3.05 (1.34–6.93) | 0.01 |

| DNase activity | 4/49 (8.2) | 20/82 (24.4) | 0.28 (0.09–0.86) | 0.02 ** |

| Protease activity | 21/49 (42.9) | 39/82 (47.6) | 0.83 (0.41–1.68) | 0.60 |

| Hemolytic activity | 37/49 (75.5) | 51/82 (62.2) | 1.87 (0.85–4.13) | 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ferreira, P.A.A.; Roso, L.D.C.; Freitas, D.A.; Bressani, A.P.P.; Ferreira, P.H.d.C.; Bodevan, E.C.; Moura, C.R.F.; Schwan, R.F.; Mendonça, V.A.; Magalhães-Guedes, K.T.; et al. Species Identification, Virulence Factors, and Antifungal Resistance in Clinical Candida Isolates from ICU Patients. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010241

Ferreira PAA, Roso LDC, Freitas DA, Bressani APP, Ferreira PHdC, Bodevan EC, Moura CRF, Schwan RF, Mendonça VA, Magalhães-Guedes KT, et al. Species Identification, Virulence Factors, and Antifungal Resistance in Clinical Candida Isolates from ICU Patients. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):241. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010241

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerreira, Paola Aparecida Alves, Lucas Daniel Cibolli Roso, Daniel Almeida Freitas, Ana Paula Pereira Bressani, Paulo Henrique da Cruz Ferreira, Emerson Cotta Bodevan, Cristiane Rocha Fagundes Moura, Rosane Freitas Schwan, Vanessa Amaral Mendonça, Karina Teixeira Magalhães-Guedes, and et al. 2026. "Species Identification, Virulence Factors, and Antifungal Resistance in Clinical Candida Isolates from ICU Patients" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010241

APA StyleFerreira, P. A. A., Roso, L. D. C., Freitas, D. A., Bressani, A. P. P., Ferreira, P. H. d. C., Bodevan, E. C., Moura, C. R. F., Schwan, R. F., Mendonça, V. A., Magalhães-Guedes, K. T., & Ramos, C. L. (2026). Species Identification, Virulence Factors, and Antifungal Resistance in Clinical Candida Isolates from ICU Patients. Microorganisms, 14(1), 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010241