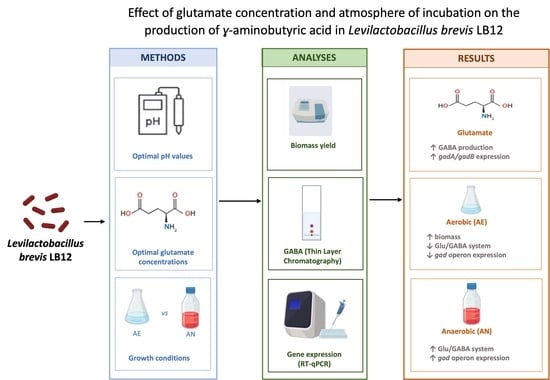

Effect of Glutamate Concentration and Atmosphere of Incubation on the Production of ɣ-Aminobutyric Acid in Levilactobacillus brevis LB12

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain and Culture Conditions

2.2. Assessment of Optimal pH for GABA Production in Buffer System

2.3. Assessment of Optimal Glutamate Concentration for GABA Production in Synthetic Medium

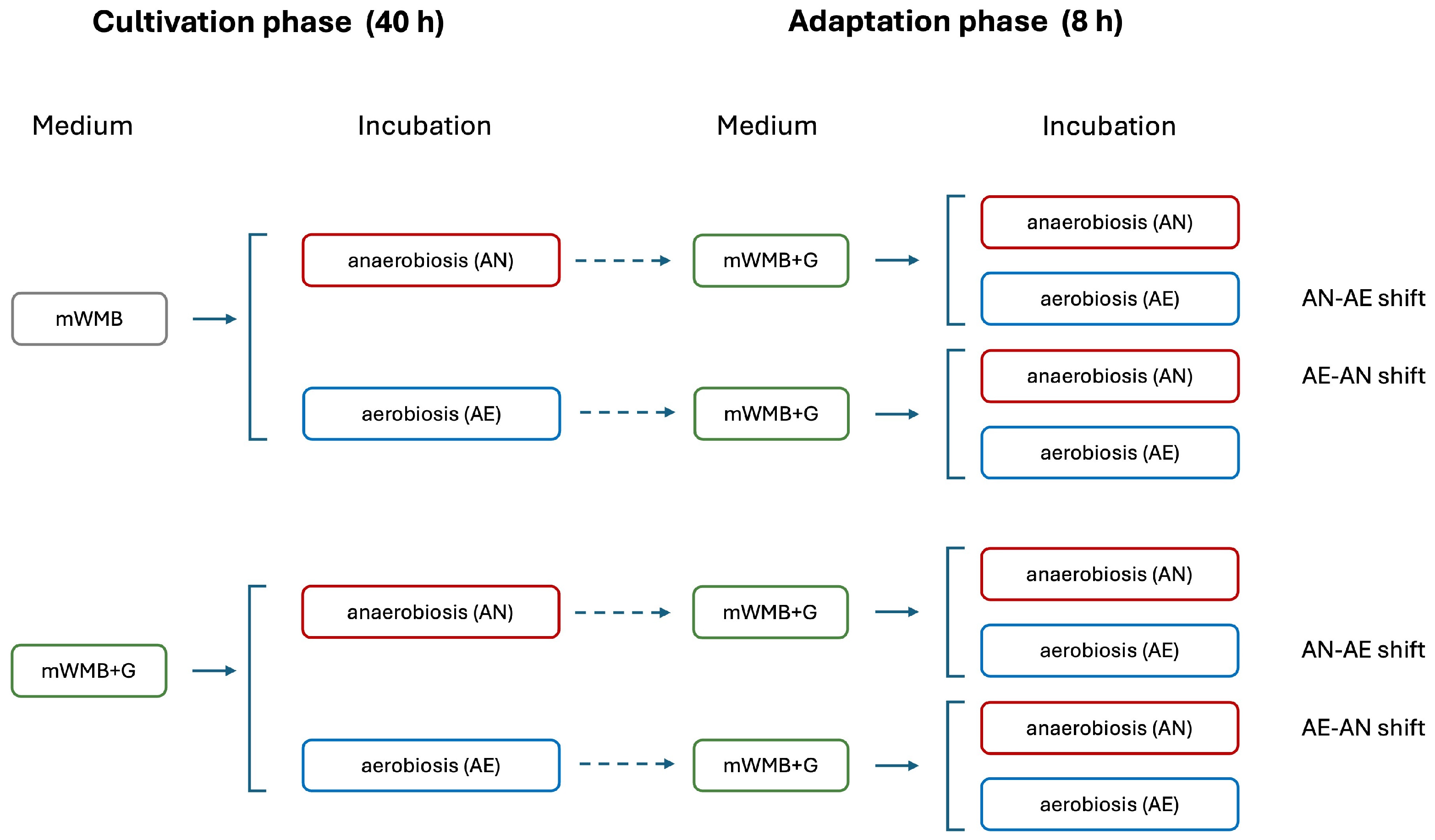

2.4. Effect of Glutamate Induction and Atmosphere of Incubation on Biomass Yield and GABA Production

2.5. Effect of Glutamate Induction and Atmosphere of Incubation on Relative Expression of GAD Operon Genes

2.5.1. In Silico Analysis and Primer Design

2.5.2. Extraction of Total RNA

2.5.3. Quantitative RT-PCR and Gene Expression Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Assessment of Optimal pH and Glutamate Concentration for GABA Production by Lvb. brevis LB12

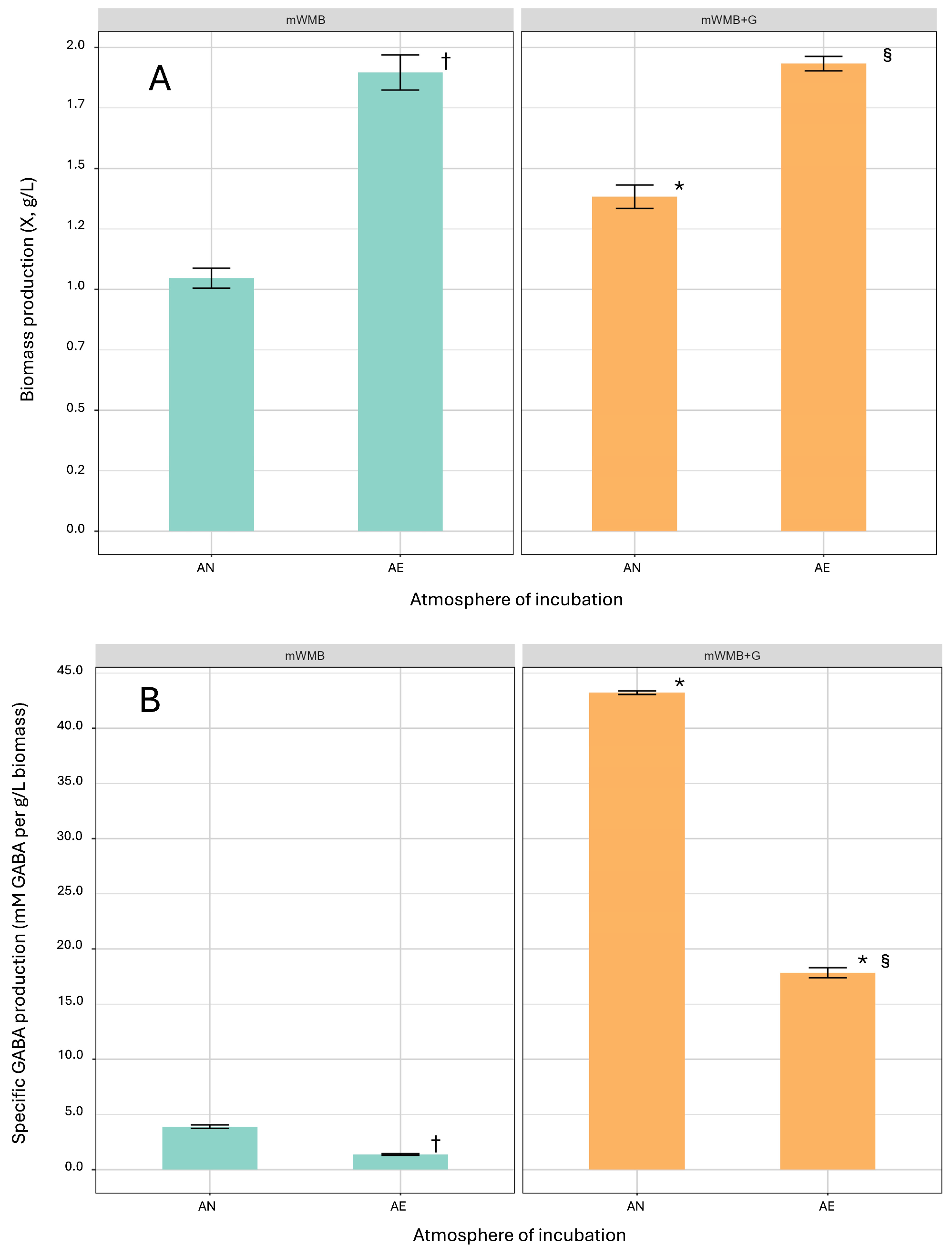

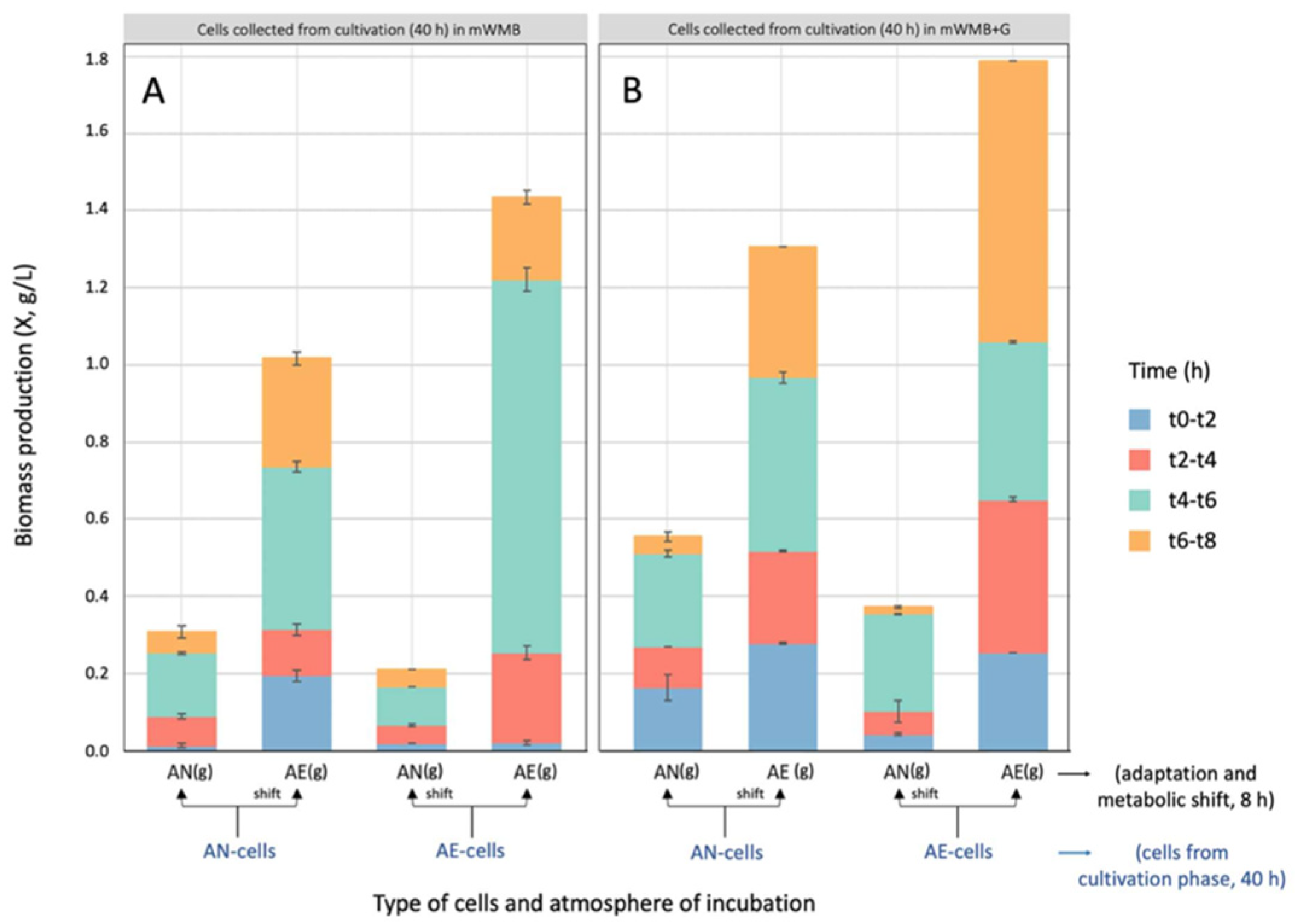

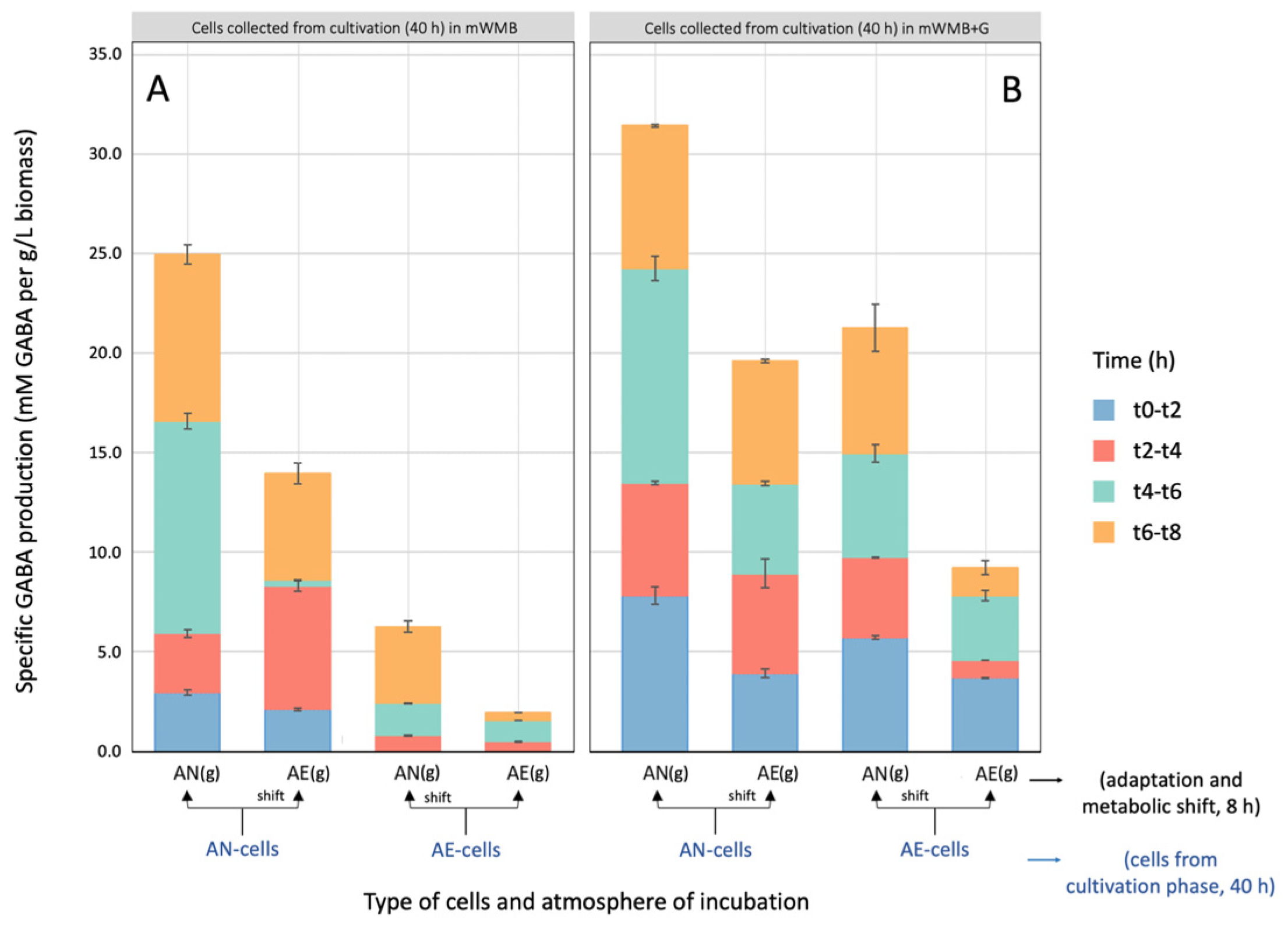

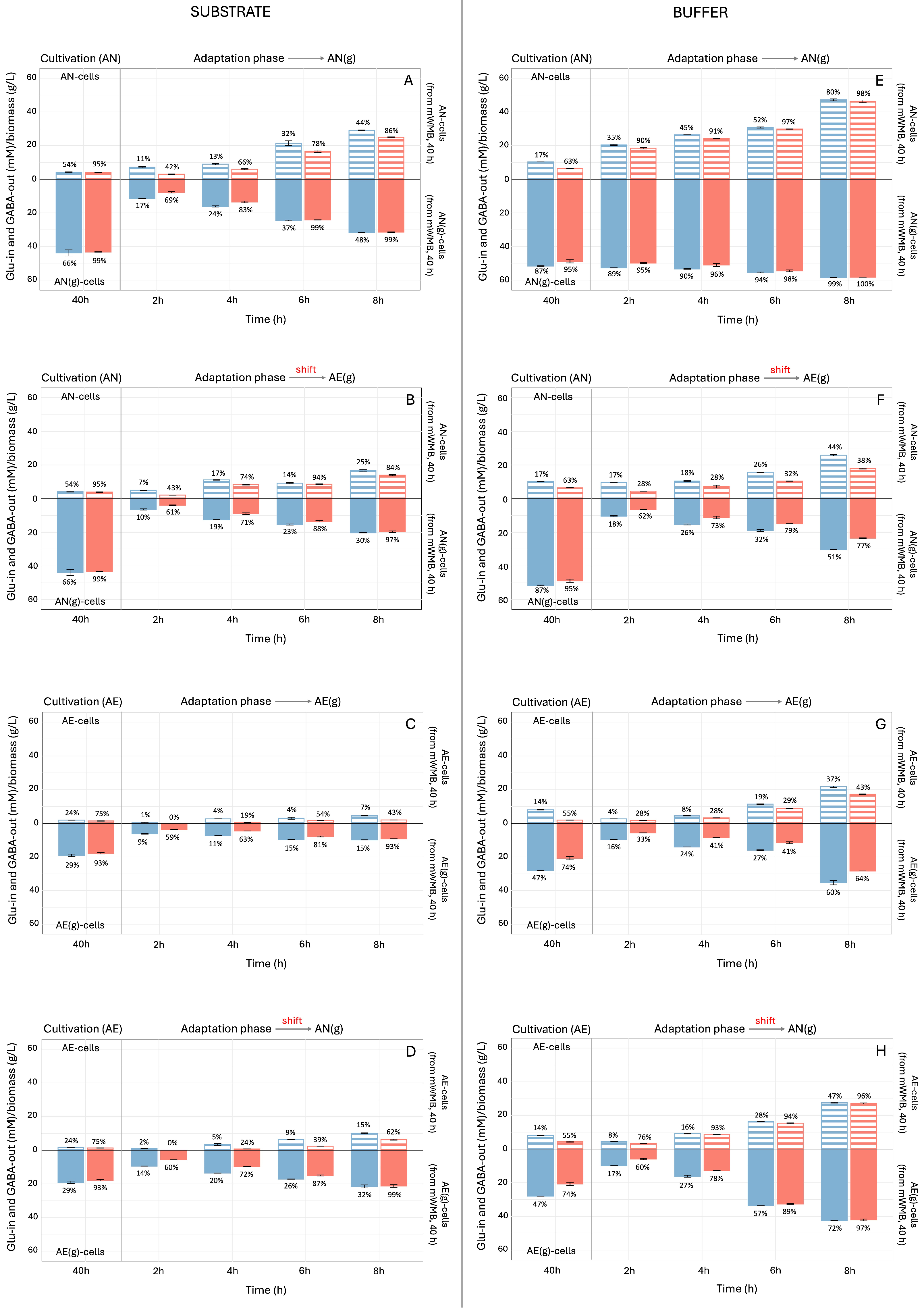

3.2. Effect of Glutamate Induction and Atmosphere of Incubation on Biomass Yield and GABA Production by Lvb. brevis LB12

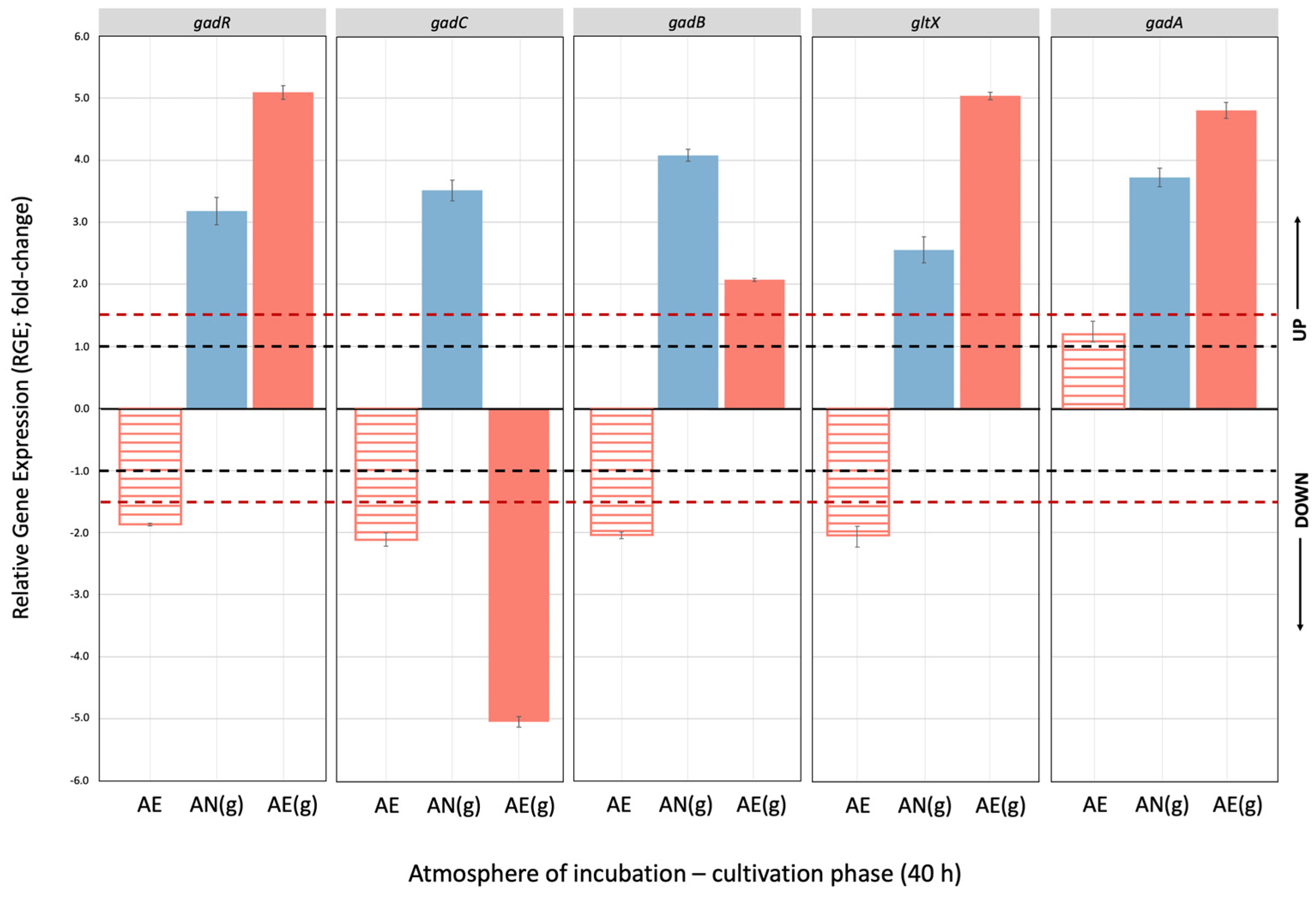

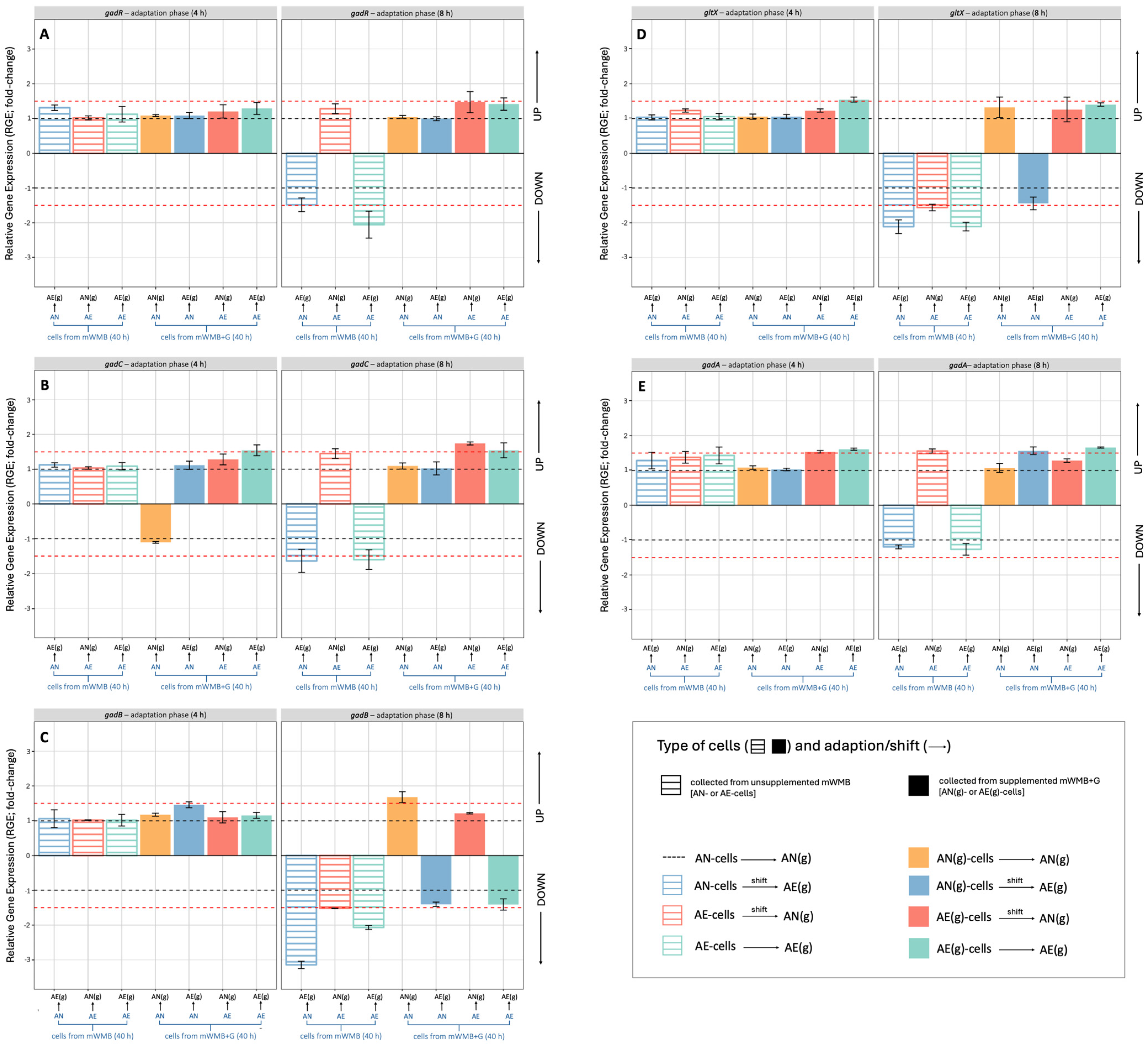

3.3. Effect of Glutamate Induction and Atmosphere of Incubation on the Relative Expression of Gad Operon in Lvb. brevis LB12

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GABA | ɣ-aminobutyric acid |

| TLC | Thin Layer Chromatography |

| Lvb | Levilactobacillus |

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

References

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, M.; Mahony, J.; Kelleher, P.; Roberts, R.J.; O’Sullivan, T.; Geertman, J.M.A.; van Sinderen, D. Comparative genome analysis of the Lactobacillus brevis species. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutada, S.; Dahikar, S.; Hassan, M.Z.; Kovaleva, E.G. A comprehensive review of probiotics and human health—Current prospective and applications. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1487641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A.; Parolin, C.; Gottardi, D.; Ricci, A.; Parpinello, G.P.; Lanciotti, R.; Patrignani, F.; Vitali, B.A. Novel GABA-producing Levilactobacillus brevis strain isolated from organic tomato as a promising probiotic. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakal, R.; Bajpai, V.K.; Baek, K.H. Production of GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) by microorganisms: A review. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2012, 43, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Wei, L.; Liu, J. Biotechnological advances and perspectives of gamma-aminobutyric acid production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icer, M.A.; Sarikaya, B.; Kocyigit, E.; Atabilen, B.; Çelik, M.N.; Capasso, R.; Budán, F. Contributions of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) produced by lactic acid bacteria on food quality and human health: Current applications and future prospects. Foods 2024, 13, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, C.; Zhao, W.; Peng, C.; Hu, S.; Fang, H.; Hua, Y.; Yao, S.; Huang, J.; Mei, L. Exploring the contributions of two glutamate decarboxylase isozymes in Lactobacillus brevis to acid resistance and γ-aminobutyric acid production. Microb. Cell Factories 2018, 17, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Poore, M.; Gerdes, S.; Nedveck, D.; Lauridsen, L.; Kristensen, H.T.; Jensen, H.M.; Byrd, P.M.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Patterson, E.; et al. Transcriptomics reveal different metabolic strategies for acid resistance and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production in select Levilactobacillus brevis strains. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, E.; Tekin, B. Molecular evolution and population genetics of glutamate decarboxylase acid- resistance pathway in lactic acid bacteria. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1027156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Chen, H. Deciphering the crucial roles of transcriptional regulator GadR on gamma-aminobutyric acid production and acid resistance in Lactobacillus brevis. Microb. Cell Factories 2019, 18, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Tun, H.M.; Law, Y.; Khafipour, E.; Shah, N.P. Common distribution of gad operon in Lactobacillus brevis and its GadA contributes to efficient GABA synthesis toward cytosolic near-neutral pH. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Miao, K.; Niyaphorn, S.; Qu, X. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid from lactic acid bacteria: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannerchelvan, S.; Rios-Solis, L.; Wong, F.W.F.; Zaidan, U.H.; Wasoh, H.; Mohamed, M.S.; Tan, J.S.; Mohamad, R.; Halim, M. Strategies for improvement of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) biosynthesis via lactic acid bacteria fermentation. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 3929–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotta, T.; Parente, E.; Ricciardi, A. Aerobic metabolism in the genus Lactobacillus: Impact on stress response and potential applications in the food industry. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 122, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotta, T.; Ricciardi, A.; Ianniello, R.G.; Storti, L.V.; Gibota, N.A.; Parente, E. Aerobic and respirative growth of heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria: A screening study. Food Microbiol. 2018, 76, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Shah, N.P. Restoration of GABA production machinery in Lactobacillus brevis by accessible carbohydrates, anaerobiosis and early acidification. Food Microbiol. 2018, 69, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotta, T.; Faraone, I.; Giavalisco, M.; Parente, E.; Lela, L.; Storti, L.V.; Ricciardi, A. The production of γ-aminobutyric acid from free and immobilized cells of Levilactobacillus brevis cultivated in anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotta, T.; Ricciardi, A.; Guidone, A.; Sacco, M.; Muscariello, L.; Mazzeo, M.F.; Cacace, G.; Parente, E. Inactivation of ccpA and Aeration Affect Growth, Metabolite Production and Stress Tolerance in Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 155, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untergasser, A.; Cutcutache, I.; Koressaar, T.; Ye, J.; Faircloth, B.C.; Remm, M.; Rozen, S.G. Primer3—New Capabilities and Interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Liu, H.; Daiyao, L.; Zhang, C.; Niu, H.; Xin, X.; Yi, H.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J. Whole-genome analysis, evaluation and regulation of in vitro and in vivo GABA production from Levilactobacillus brevis YSJ3. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 421, 110787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ba, W.; You, S.; Qi, W.; Su, R. Development of an oil-sealed anaerobic fermentation process for high production of γ-aminobutyric acid with Lactobacillus brevis isolated by directional colorimetric screening. Biochem. Eng. J. 2023, 196, 108893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, P.G.; Urquiza Martínez, M.P.; Villena, J.; Kitazawa, H.; Saavedra, L.; Hebert, E.M. Comprehensive characterization of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production by Levilactobacillus brevis CRL 2013: Insights from physiology, genomics, and proteomics. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1408624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lavanga, E.; Giavalisco, M.; Ricciardi, A.; Zotta, T. Effect of Glutamate Concentration and Atmosphere of Incubation on the Production of ɣ-Aminobutyric Acid in Levilactobacillus brevis LB12. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010108

Lavanga E, Giavalisco M, Ricciardi A, Zotta T. Effect of Glutamate Concentration and Atmosphere of Incubation on the Production of ɣ-Aminobutyric Acid in Levilactobacillus brevis LB12. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleLavanga, Emanuela, Marilisa Giavalisco, Annamaria Ricciardi, and Teresa Zotta. 2026. "Effect of Glutamate Concentration and Atmosphere of Incubation on the Production of ɣ-Aminobutyric Acid in Levilactobacillus brevis LB12" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010108

APA StyleLavanga, E., Giavalisco, M., Ricciardi, A., & Zotta, T. (2026). Effect of Glutamate Concentration and Atmosphere of Incubation on the Production of ɣ-Aminobutyric Acid in Levilactobacillus brevis LB12. Microorganisms, 14(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010108