Understanding Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms: Quorum Sensing, c-di-GMP Signaling, and Emerging Antibiofilm Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Architectural and Molecular Foundations of P. aeruginosa Biofilms

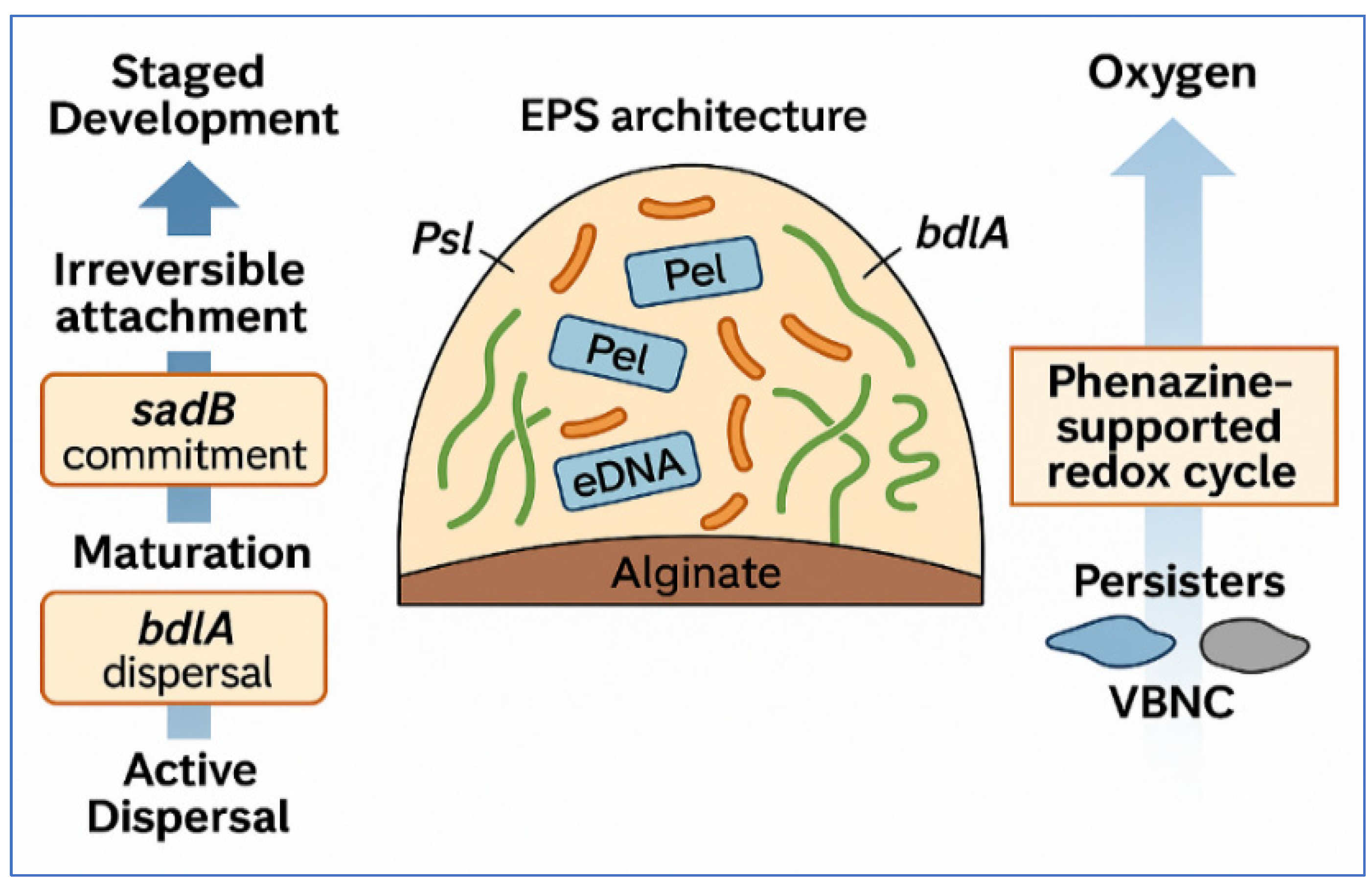

2.1. Staged Development: Attachment, Maturation, and Dispersal (pel, psl, algD, sadB, and bdlA)

2.2. Matrix Composition and Mechanics: Polysaccharides, Proteins, eDNA, and Host Inputs (NETs, Mucins)

2.3. Spatial and Metabolic Heterogeneity: Oxygen and Nutrient Gradients, Persisters, and VBNC Cells

3. Quorum Networks: The Social Intelligence of Biofilms

3.1. Hierarchical QS Systems Involving las, rhl, pqs, and iqs and Their Cross-Regulation

3.2. Molecular Integration Between QS and c-di-GMP

3.3. QS-Controlled Virulence Portfolio

3.4. Polymicrobial and Host Interactions

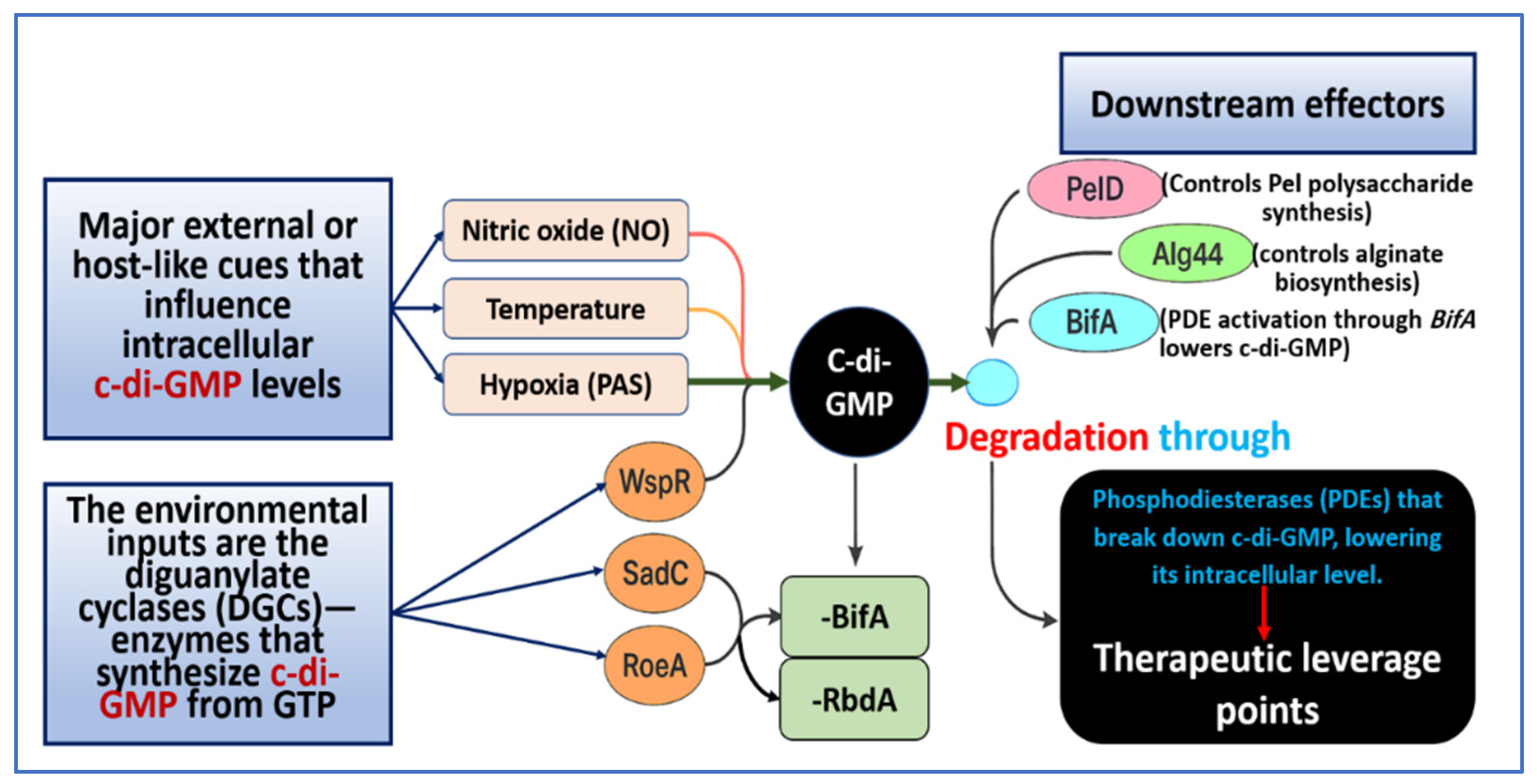

4. c-di-GMP Dynamics: The Molecular Switchboard of Biofilm Formation

4.1. Synthesis and Degradation Enzymes Involving DGCs and PDEs

4.2. Effectors and Downstream Targets

4.3. Environmental and Host Signals Modulating c-di-GMP Turnover

4.4. Interplay with QS and Stress Pathways: Fine-Tuning Motility, EPS Synthesis, and Dispersal

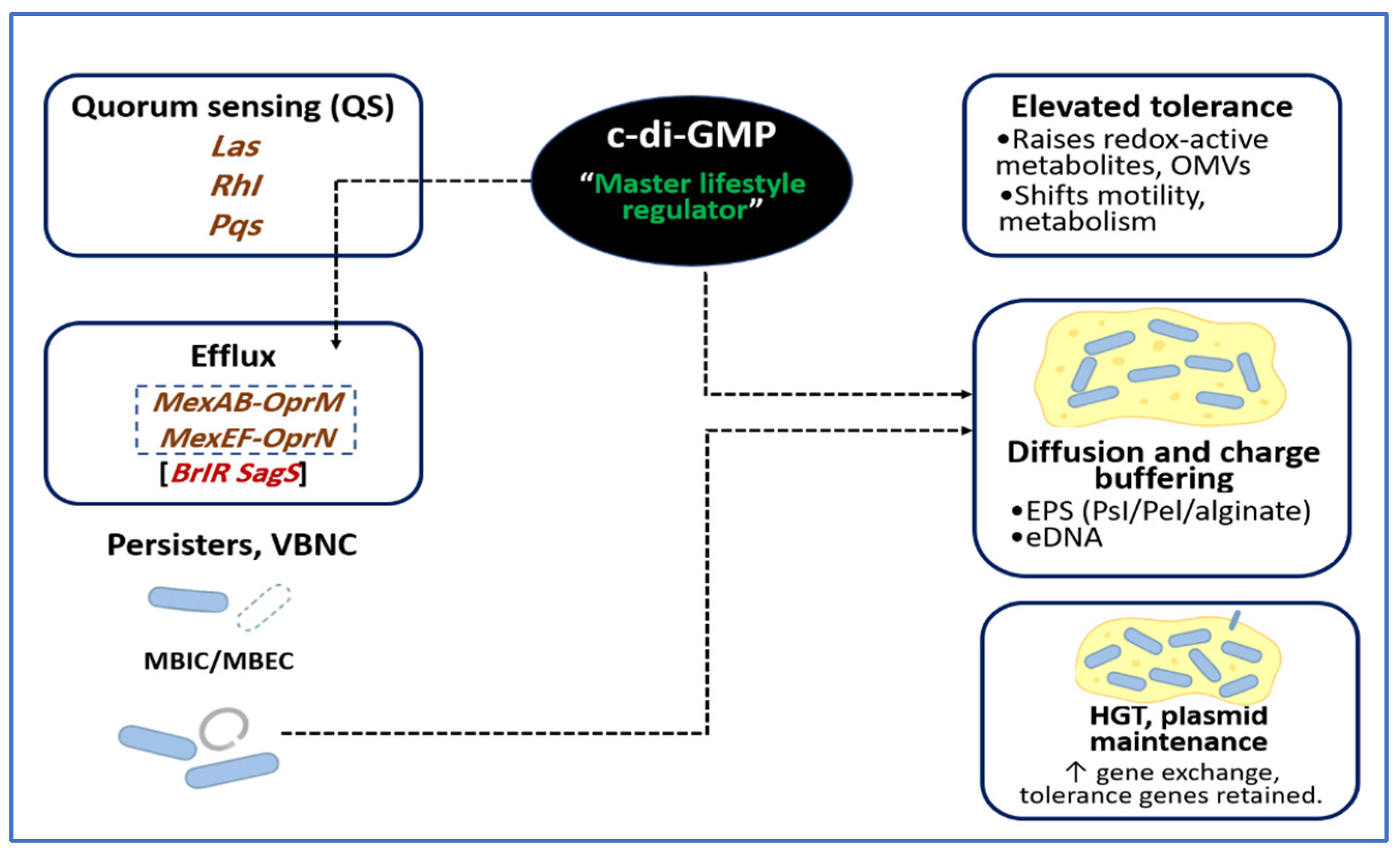

5. Antimicrobial Tolerance and Persistence of the Biofilm Code

5.1. EPS Mediated Diffusion Restriction and Charge Buffering

5.2. Efflux Pumps and Stress Regulons

5.3. Dormant, Persister, and VBNC Populations

5.4. Horizontal Gene Transfer and Plasmid Stabilization Inside the Matrix

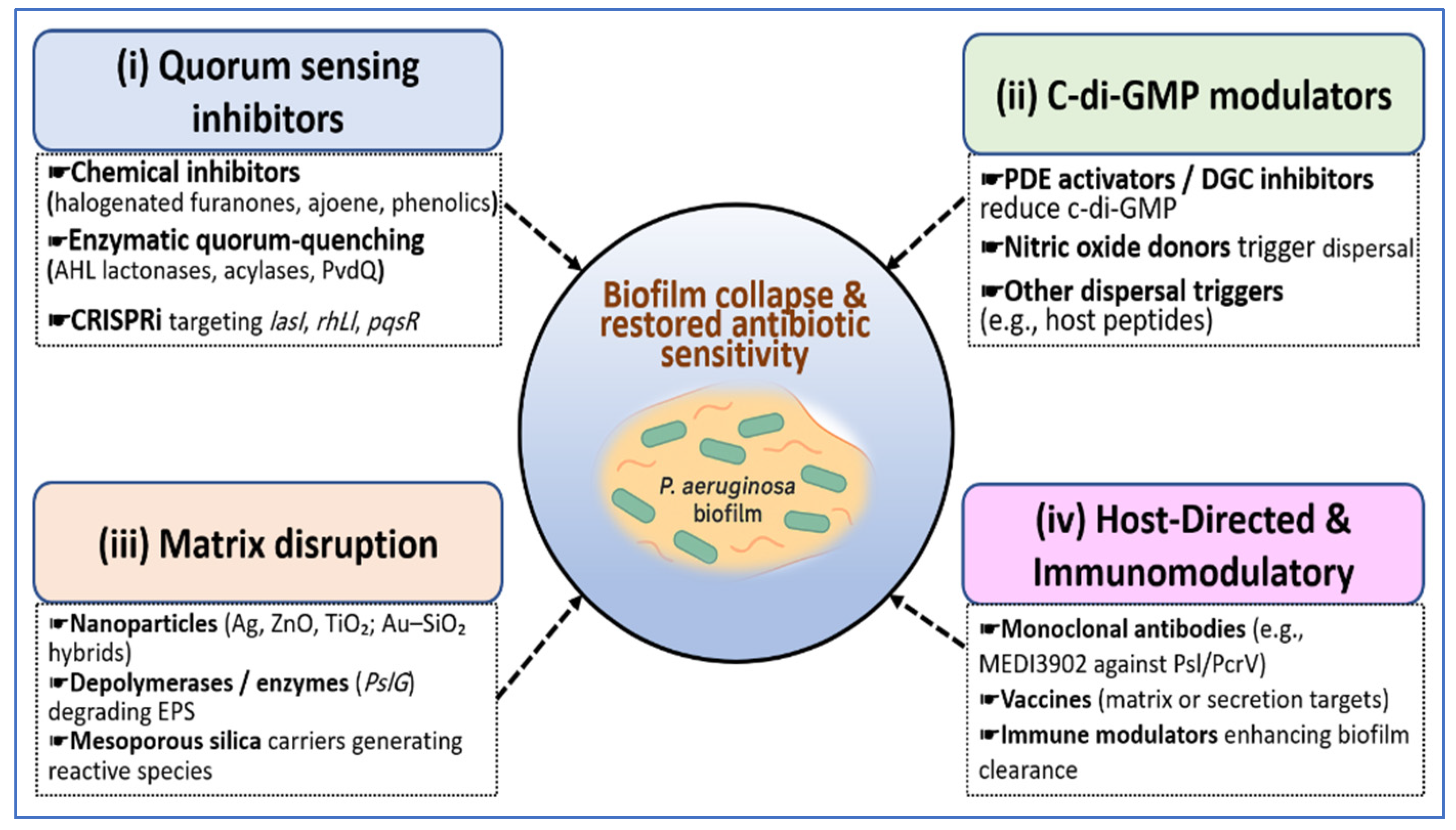

6. Cracking the Code: Emerging Strategies to Rewire or Disrupt the Network

6.1. Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors (QSIs) and Quorum-Quenching Enzymes

6.2. c-di-GMP Modulators and Dispersal Triggers

6.3. Nanoparticle-Based Synergistic Systems

6.4. Phage and Phage-Derived Enzymes

6.5. Host-Directed and Immunomodulatory Therapies

7. Diagnostic and Analytical Horizons: Reading the Biofilm Code

7.1. Advanced Imaging: CLSM, OCT, and Raman Mapping as a Spatial Code

7.2. Omics Integration: Transcriptomic and Proteomic Mapping of QS and c-di-GMP Signatures

7.3. Rapid Diagnostics: MALDI-TOF Biofilm Profiling, Impedance Biosensing, and Microfluidic Biofilm on Chip Models

7.4. AI and Systems Biology: Predicting Biofilm Phenotypes and QSI Efficacy with ML

8. Challenges, Translational Barriers, and One Health Perspectives

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: An emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciofu, O.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Tolerance and resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to antimicrobial agents—How P. aeruginosa can escape antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice, N.M.; Bedi, B.; Sadikot, R.T. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: Host response and clinical implications in lung infections. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 58, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hentzer, M.; Teitzel, G.M.; Balzer, G.J.; Heydorn, A.; Molin, S.; Givskov, M.; Parsek, M.R. Alginate overproduction affects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm structure and function. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 5395–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau-Marquis, S.; Stanton, B.A.; O’Toole, G.A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation in the cystic fibrosis airway. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 21, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, O.; Butnarasu, C.; Visentin, S.; Reimhult, E. Interplay between biofilm microenvironment and pathogenicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung chronic infection. Biofilm 2022, 4, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, K.S.; Weaver, A.J., Jr.; Qian, L.; You, T.; Chen, P.; Karna, S.R.; Fourcaudot, A.B.; Sebastian, E.A.; Abercrombie, J.J.; Pineda, U. Development of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in partial-thickness burn wounds using a Sprague-Dawley rat model. J. Burn Care Res. 2019, 40, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, K.S.; Weaver, A.J., Jr.; Karna, S.R.; You, T.; Chen, P.; Stryk, S.V.; Qian, L.; Pineda, U.; Abercrombie, J.J.; Leung, K.P. Formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in full-thickness scald burn wounds in rats. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.J.; Records, A.R.; Orr, M.W.; Linden, S.B.; Lee, V.T. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by exopolysaccharide-independent biofilms. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 2048–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Perotin, S.; Ramirez, P.; Marti, V.; Sahuquillo, J.M.; Gonzalez, E.; Calleja, I.; Menendez, R.; Bonastre, J. Implications of endotracheal tube biofilm in ventilator-associated pneumonia response: A state of concept. Crit. Care 2012, 16, R93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, A.; Fouquenet, D.; Morello, E.; Henry, C.; Georgeault, S.; Si-Tahar, M.; Hervé, V. Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm present in endotracheal tubes by poly-l-lysine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00564-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, A.; Sahu, R.; Owen, D.R.; Dennis, V.A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa reference strains PAO1 and PA14: A genomic, phenotypic, and therapeutic review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1023523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stover, C.; Pham, X.; Erwin, A.; Mizoguchi, S.; Warrener, P.; Hickey, M.; Brinkman, F.; Hufnagle, W.; Kowalik, D.; Lagrou, M. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 2000, 406, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.J.; Doing, G.; Neff, S.L.; Reiter, T.; Hogan, D.A.; Greene, C.S. Compendium-wide analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa core and accessory genes reveals transcriptional patterns across strains PAO1 and PA14. MSystems 2023, 8, e00342-00322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, A.R.; Allan, R.N.; Valentin, J.D.; Castañeda Ocampo, O.E.; Somerville, V.; Pietsch, F.; Buhmann, M.T.; West, J.; Skipp, P.J.; van der Mei, H.C. An integrated model system to gain mechanistic insights into biofilm-associated antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa MPAO1. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2020, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Zhang, L. The hierarchy quorum sensing network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Cell 2015, 6, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, S.; Zhou, D.; Hou, Q.; Li, G.; Han, H. A comprehensive review of the pathogenic mechanisms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Synergistic effects of virulence factors, quorum sensing, and biofilm formation. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1619626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, M.; Filloux, A. Biofilms and cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) signaling: Lessons from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 12547–12555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchma, S.; Ballok, A.; Merritt, J.; Hammond, J.; Lu, W.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; O’Toole, G.A. Cyclic di-GMP-mediated repression of swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 requires the MotAB stator. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 197, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberg, M.; Kragh, K.N.; Fritz, B.; Kirkegaard, J.B.; Tolker-Nielsen, T.; Bjarnsholt, T. Cyclic-di-GMP signaling controls metabolic activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraud, N.; Schleheck, D.; Klebensberger, J.; Webb, J.S.; Hassett, D.J.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Nitric oxide signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms mediates phosphodiesterase activity, decreased cyclic di-GMP levels, and enhanced dispersal. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 7333–7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutruzzolà, F.; Frankenberg-Dinkel, N. Origin and impact of nitric oxide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 2016, 198, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasamiravaka, T.; Labtani, Q.; Duez, P.; El Jaziri, M. The formation of biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A review of the natural and synthetic compounds interfering with control mechanisms. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 759348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Conover, M.; Lu, H.; Parsek, M.R.; Bayles, K.; Wozniak, D.J. Assembly and development of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caiazza, N.C.; O’Toole, G.A. SadB is required for the transition from reversible to irreversible attachment during biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 4476–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, Y.; Sporny, M.; Brochin, Y.; Piscon, B.; Roth, S.; Zander, I.; Nisani, M.; Shoshani, S.; Yaron, O.; Karako-Lampert, S. SadB, a mediator of AmrZ proteolysis and biofilm development in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papangeli, M.; Luckett, J.; Heeb, S.; Alexander, M.R.; Williams, P.; Dubern, J.-F. SadB acts as a master regulator modulating Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenicity. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, C.; Byrd, M.; Wozniak, D.J. Role of polysaccharides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2007, 10, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz Nizer, W.S.; Allison, K.N.; Adams, M.E.; Vargas, M.A.; Ahmed, D.; Beaulieu, C.; Raju, D.; Cassol, E.; Howell, P.L.; Overhage, J. The role of exopolysaccharides Psl and Pel in resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the oxidative stressors sodium hypochlorite and hydrogen peroxide. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e00922–e00924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, K.M.; Irie, Y.; Tart, C.S.; Urbano, R.; Whitney, J.C.; Ryder, C.; Howell, P.L.; Wozniak, D.J.; Parsek, M.R. The Pel and Psl polysaccharides provide Pseudomonas aeruginosa structural redundancy within the biofilm matrix. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1913–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, D.J.; Wyckoff, T.J.; Starkey, M.; Keyser, R.; Azadi, P.; O’Toole, G.A.; Parsek, M.R. Alginate is not a significant component of the extracellular polysaccharide matrix of PA14 and PAO1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 7907–7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, R.; Kohn, S.; Hwang, S.-H.; Hassett, D.J.; Sauer, K. BdlA, a chemotaxis regulator essential for biofilm dispersion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 7335–7343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, O.E.; Sauer, K. Dispersion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires an unusual posttranslational modification of BdlA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16690–16695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, O.E.; Cherny, K.E.; Sauer, K. The diguanylate cyclase GcbA facilitates Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm dispersion by activating BdlA. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Petrova, O.E.; Su, S.; Lau, G.W.; Panmanee, W.; Na, R.; Hassett, D.J.; Davies, D.G.; Sauer, K. BdlA, DipA and induced dispersion contribute to acute virulence and chronic persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos da Silva, D.; Matwichuk, M.L.; Townsend, D.O.; Reichhardt, C.; Lamba, D.; Wozniak, D.J.; Parsek, M.R. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa lectin LecB binds to the exopolysaccharide Psl and stabilizes the biofilm matrix. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Mauff, F.; Razvi, E.; Reichhardt, C.; Sivarajah, P.; Parsek, M.R.; Howell, P.L.; Sheppard, D.C. The Pel polysaccharide is predominantly composed of a dimeric repeat of α-1, 4 linked galactosamine and N-acetylgalactosamine. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Cai, Z.; Duan, X.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, H.; Han, S.; Yu, K.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Pseudomonas aeruginosa modulates alginate biosynthesis and type VI secretion system in two critically ill COVID-19 patients. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichhardt, C. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix protein CdrA has similarities to other fibrillar adhesin proteins. J. Bacteriol. 2023, 205, e00019–e00023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, J.N.; Yildiz, F.H. Biofilm matrix proteins. Microb. Biofilms 2015, 3, 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio, H.; Rice, C.V. The role of extracellular DNA in the formation, architecture, stability, and treatment of bacterial biofilms. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 2129–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Lei, Y.; Tang, X.; Li, D.; Liang, J.; Luo, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Ye, L.; Kong, J. DNase inhibits early biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-or Staphylococcus aureus-induced empyema models. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 917038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanabalasuriar, A.; Scott, B.N.V.; Peiseler, M.; Willson, M.E.; Zeng, Z.; Warrener, P.; Keller, A.E.; Surewaard, B.G.J.; Dozier, E.A.; Korhonen, J.T. Neutrophil extracellular traps confine Pseudomonas aeruginosa ocular biofilms and restrict brain invasion. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 526–536.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, R.M.; An, D.; Hupp, J.T.; Singh, P.K.; Parsek, M.R. Mucin–Pseudomonas aeruginosa interactions promote biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 59, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Co, J.Y.; Cárcamo-Oyarce, G.; Billings, N.; Wheeler, K.M.; Grindy, S.C.; Holten-Andersen, N.; Ribbeck, K. Mucins trigger dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2018, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, L.E.; Okegbe, C.; Price-Whelan, A.; Sakhtah, H.; Hunter, R.C.; Newman, D.K. Bacterial community morphogenesis is intimately linked to the intracellular redox state. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, K.S.; Richards, L.A.; Perez-Osorio, A.C.; Pitts, B.; McInnerney, K.; Stewart, P.S.; Franklin, M.J. Heterogeneity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms includes expression of ribosome hibernation factors in the antibiotic-tolerant subpopulation and hypoxia-induced stress response in the metabolically active population. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 2062–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, N.R.; Kern, S.E.; Newman, D.K. Phenazine redox cycling enhances anaerobic survival in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by facilitating generation of ATP and a proton-motive force. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 92, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, W.C.; Zhang, Y.; Bendebury, A.; Hartel, A.J.; Shepard, K.L.; Dietrich, L.E. Phenazine oxidation by a distal electrode modulates biofilm morphogenesis. Biofilm 2020, 2, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiessl, K.T.; Hu, F.; Jo, J.; Nazia, S.Z.; Wang, B.; Price-Whelan, A.; Min, W.; Dietrich, L.E. Phenazine production promotes antibiotic tolerance and metabolic heterogeneity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.; Alexandre, K.; Etienne, M. Tolerance and persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in biofilms exposed to antibiotics: Molecular mechanisms, antibiotic strategies and therapeutic perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žiemytė, M.; Carda-Diéguez, M.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.C.; Ventero, M.P.; Mira, A.; Ferrer, M.D. Real-time monitoring of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growth dynamics and persister cells’ eradication. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 2062–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnath, A.P.; Suodha Suoodh, M.; Chellappan, D.K.; Chellian, J.; Palaniveloo, K. Bacterial persister cells and development of antibiotic resistance in chronic infections: An update. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 81, 12958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Huang, Z.; Liu, C. Metabolism differences of biofilm and planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa in viable but nonculturable state induced by chlorine stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilks, S.A.; Koerfer, V.V.; Prieto, J.A.; Fader, M.; Keevil, C.W. Biofilm development on urinary catheters promotes the appearance of viable but nonculturable bacteria. MBio 2021, 12, e03584-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Liu, C. Temporal metabolic dynamics and heterogeneity of viable but nonculturable Pseudomonas aeruginosa induced by chlorine disinfection at single-cell resolution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korshoj, L.E.; Kielian, T. Bacterial single-cell RNA sequencing captures biofilm transcriptional heterogeneity and differential responses to immune pressure. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekimpe, V.; Deziel, E. Revisiting the quorum-sensing hierarchy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: The transcriptional regulator RhlR regulates LasR-specific factors. Microbiology 2009, 155, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltner, J.B.; Wolter, D.J.; Pope, C.E.; Groleau, M.-C.; Smalley, N.E.; Greenberg, E.P.; Mayer-Hamblett, N.; Burns, J.; Déziel, E.; Hoffman, L.R. LasR variant cystic fibrosis isolates reveal an adaptable quorum-sensing hierarchy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MBio 2016, 7, e01513-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Aceves, M.P.; Cocotl-Yañez, M.; Servín-González, L.; Soberón-Chávez, G. The Rhl quorum-sensing system is at the top of the regulatory hierarchy under phosphate-limiting conditions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 2021, 203, e00475-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya, J.; Montagut, E.-J.; Marco, M.-P. Correction: Analysing the integrated quorum sensing (iqs) system and its potential role in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1634997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, M.A.; Blackwell, H.E. Chemical genetics reveals environment-specific roles for quorum sensing circuits in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L.R.; Kulasekara, H.D.; Emerson, J.; Houston, L.S.; Burns, J.L.; Ramsey, B.W.; Miller, S.I. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants are associated with cystic fibrosis lung disease progression. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2009, 8, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanek, K.A.; Taylor, I.R.; Richael, E.K.; Lasek-Nesselquist, E.; Bassler, B.L.; Paczkowski, J.E. The PqsE-RhlR interaction regulates RhlR DNA binding to control virulence factor production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02108–e02121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feathers, J.R.; Richael, E.K.; Simanek, K.A.; Fromme, J.C.; Paczkowski, J.E. Structure of the RhlR-PqsE complex from Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals mechanistic insights into quorum-sensing gene regulation. Structure 2022, 30, 1626–1636.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groleau, M.-C.; de Oliveira Pereira, T.; Dekimpe, V.; Déziel, E. PqsE is essential for RhlR-dependent quorum sensing regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Msystems 2020, 5, e00194-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchadi, B.V.; Derringer, J.J.; Detweiler, A.K.; Taylor, I.R. PqsE adapts the activity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing transcription factor RhlR to both autoinducer concentration and promoter sequence identity. J. Bacteriol. 2025, 207, e00516-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coggan, K.A.; Wolfgang, M.C. Global regulatory pathways and cross-talk control Pseudomonas aeruginosa environmental lifestyle and virulence phenotype. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2012, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J.N.; Lamont, S.; Wozniak, D.J.; Dandekar, A.A.; Parsek, M.R. Quorum sensing regulation of Psl polysaccharide production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2024, 206, e00312–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuragi, Y.; Kolter, R. Quorum-sensing regulation of the biofilm matrix genes (pel) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 5383–5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.-G.; O’Toole, G.A. c-di-GMP and its effects on biofilm formation and dispersion: A Pseudomonas aeruginosa review. Microb. Biofilms 2015, 3, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L.-H. Modulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm dispersal by a cyclic-Di-GMP phosphodiesterase with a putative hypoxia-sensing domain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 8160–8173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgert, S.R.; Henke, S.; Witzgall, F.; Schmelz, S.; Zur Lage, S.; Hotop, S.-K.; Stephen, S.; Lübken, D.; Krüger, J.; Gomez, N.O. Moonlighting chaperone activity of the enzyme PqsE contributes to RhlR-controlled virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, J.C.; Whitfield, G.B.; Marmont, L.S.; Yip, P.; Neculai, A.M.; Lobsanov, Y.D.; Robinson, H.; Ohman, D.E.; Howell, P.L. Dimeric c-di-GMP is required for post-translational regulation of alginate production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 12451–12462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Rybtke, M.; Kragh, K.N.; Johnson, O.; Schicketanz, M.; Zhang, Y.E.; Andersen, J.B.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Transcription of the alginate operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is regulated by c-di-GMP. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00675-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okkotsu, Y.; Little, A.S.; Schurr, M.J. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgZR two-component system coordinates multiple phenotypes. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazire, A.; Shioya, K.; Soum-Soutéra, E.; Bouffartigues, E.; Ryder, C.; Guentas-Dombrowsky, L.; Hémery, G.; Linossier, I.; Chevalier, S.; Wozniak, D.J. The sigma factor AlgU plays a key role in formation of robust biofilms by nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 3001–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, O.E.; Sauer, K. SagS contributes to the motile-sessile switch and acts in concert with BfiSR to enable Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 6614–6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almblad, H.; Harrison, J.J.; Rybtke, M.; Groizeleau, J.; Givskov, M.; Parsek, M.R.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. The cyclic AMP–Vfr signaling pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is inhibited by cyclic di-GMP. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 2190–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yang, G.; Debru, A.B.; Li, P.; Zong, L.; Li, P.; Xu, T.; Wu, W.; Jin, S.; Bao, Q. SuhB regulates the motile-sessile switch in Pseudomonas aeruginosa through the Gac/Rsm pathway and c-di-GMP signaling. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, C.; Pu, Q.; Deng, X.; Lan, L.; Liang, H.; Song, X.; Wu, M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances and emerging therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallonardi, G.; Letizia, M.; Mellini, M.; Frangipani, E.; Halliday, N.; Heeb, S.; Cámara, M.; Visca, P.; Imperi, F.; Leoni, L. Alkyl-quinolone-dependent quorum sensing controls prophage-mediated autolysis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa colony biofilms. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1183681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.C.; Florez, C.; Dunshee, E.B.; Lieber, A.D.; Terry, M.L.; Light, C.J.; Schertzer, J.W. Pseudomonas quinolone signal-induced outer membrane vesicles enhance biofilm dispersion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mSphere 2020, 5, e01109-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florez, C.; Raab, J.E.; Cooke, A.C.; Schertzer, J.W. Membrane distribution of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal modulates outer membrane vesicle production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 2017, 8, e01034-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.; Séguin, D.L.; Asselin, A.-E.; Déziel, E.; Cantin, A.M.; Frost, E.H.; Michaud, S.; Malouin, F. Staphylococcus aureus sigma B-dependent emergence of small-colony variants and biofilm production following exposure to Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline-N-oxide. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, R. Respiration and small-colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, GPP3-0069-2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman-Rodriguez, F.; Kim, J.; Parker, D.; Boyd, J.M. An effective response to respiratory inhibition by a Pseudomonas aeruginosa-excreted quinoline promotes Staphylococcus aureus fitness and survival in co-culture. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazi, G.; O’Toole, G.A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alters Staphylococcus aureus sensitivity to vancomycin in a biofilm model of cystic fibrosis infection. mBio 2017, 8, e00873-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, L.; Biswas, R.; Schlag, M.; Bertram, R.; Götz, F. Small-colony variant selection as a survival strategy for Staphylococcus aureus in the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 6910–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Rudden, M.; Smyth, T.J.; Dooley, J.S.; Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M. Natural quorum sensing inhibitors effectively downregulate gene expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 3521–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.; Ham, S.-Y.; Nam, S.; Kim, M.; Lee, K.Y.; Park, H.-D.; Byun, Y. Recent advance in small molecules targeting RhlR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Urretavizcaya, B.; Vilaplana, L.; Marco, M.-P. Strategies for quorum sensing inhibition as a tool for controlling Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L.R.; Déziel, E.; d’Argenio, D.A.; Lépine, F.; Emerson, J.; McNamara, S.; Gibson, R.L.; Ramsey, B.W.; Miller, S.I. Selection for Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants due to growth in the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19890–19895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraza, J.P.; Whiteley, M. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa antimicrobial affects the biogeography but not fitness of Staphylococcus aureus during coculture. mBio 2021, 12, e00047-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Oglesby-Sherrouse, A.G. Interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus during co-cultivations and polymicrobial infections. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 6141–6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallett, R.; Leslie, L.J.; Lambert, P.A.; Milic, I.; Devitt, A.; Marshall, L.J. Anaerobiosis influences virulence properties of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates and the interaction with Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Fernandes, M.; Gomez, A.-C.; Bravo, M.; Huedo, P.; Coves, X.; Prat-Aymerich, C.; Gibert, I.; Lacoma, A.; Yero, D. Strain-specific interspecies interactions between co-isolated pairs of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with tracheobronchitis or bronchial colonization. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.; Narh, J.K.; Urlaub, M.; Jankiewicz, O.; Johnson, C.; Livingston, B.; Dahl, J.-U. Pseudomonas aeruginosa kills Staphylococcus aureus in a polyphosphate-dependent manner. mSphere 2024, 9, e00686-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E.; Safrin, M.; Abrams, W.R.; Rosenbloom, J.; Ohman, D.E. Inhibitors and specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa LasA. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 9884–9889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keim, K.; Bhattacharya, M.; Crosby, H.A.; Jenul, C.; Mills, K.; Schurr, M.; Horswill, A. Polymicrobial interactions between Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa promote biofilm formation and persistence in chronic wound infections. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotterbeekx, A.; Kumar-Singh, S.; Goossens, H.; Malhotra-Kumar, S. In vivo and In vitro Interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus spp. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Kostylev, M.; Kim, D.Y.; Smalley, N.E.; Salukhe, I.; Greenberg, E.P.; Dandekar, A.A. Evolution of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing hierarchy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7027–7032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggle, S.P.; Matthijs, S.; Wright, V.J.; Fletcher, M.P.; Chhabra, S.R.; Lamont, I.L.; Kong, X.; Hider, R.C.; Cornelis, P.; Cámara, M. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-quinolone signal molecules HHQ and PQS play multifunctional roles in quorum sensing and iron entrapment. Chem. Biol. 2007, 14, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, X. The Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS): Not just for quorum sensing anymore. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Déziel, E.; Gopalan, S.; Tampakaki, A.P.; Lépine, F.; Padfield, K.E.; Saucier, M.; Xiao, G.; Rahme, L.G. The contribution of MvfR to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis and quorum sensing circuitry regulation: Multiple quorum sensing-regulated genes are modulated without affecting lasRI, rhlRI or the production of N-acyl-L-homoserine lactones. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 998–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Wu, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Chang, C.; Dong, Y.; Williams, P.; Zhang, L.-H. A cell–cell communication signal integrates quorum sensing and stress response. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merighi, M.; Lee, V.T.; Hyodo, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Lory, S. The second messenger bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-GMP and its PilZ domain-containing receptor Alg44 are required for alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 65, 876–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, M.; Filloux, A. Multiple roles of c-di-GMP signaling in bacterial pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 73, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Sauer, K. Controlling biofilm development through cyclic di-GMP signaling. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022, 1386, 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Güvener, Z.T.; Harwood, C.S. Subcellular location characteristics of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa GGDEF protein, WspR, indicate that it produces cyclic-di-GMP in response to growth on surfaces. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 66, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangyutitham, V.; Güvener, Z.T.; Harwood, C.S. Subcellular clustering of the phosphorylated WspR response regulator protein stimulates its diguanylate cyclase activity. mBio 2013, 4, e00242-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neal, L.; Baraquet, C.; Suo, Z.; Dreifus, J.E.; Peng, Y.; Raivio, T.L.; Wozniak, D.J.; Harwood, C.S.; Parsek, M.R. The Wsp system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa links surface sensing and cell envelope stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2117633119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Han, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, S.; Kong, W.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y. FlhF affects the subcellular clustering of WspR through HsbR in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e01548-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.E.; Webster, S.S.; Diepold, A.; Kuchma, S.L.; Bordeleau, E.; Armitage, J.P.; O’Toole, G.A. Flagellar stators stimulate c-di-GMP production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00741-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, J.H.; Ha, D.-G.; Cowles, K.N.; Lu, W.; Morales, D.K.; Rabinowitz, J.; Gitai, Z.; O’Toole, G.A. Specific control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa surface-associated behaviors by two c-di-GMP diguanylate cyclases. mBio 2010, 1, e00183-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchma, S.L.; Brothers, K.M.; Merritt, J.H.; Liberati, N.T.; Ausubel, F.M.; O’Toole, G.A. BifA, a cyclic-Di-GMP phosphodiesterase, inversely regulates biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 8165–8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liew, C.W.; Wong, Y.H.; Tan, S.T.; Poh, W.H.; Manimekalai, M.S.; Rajan, S.; Xin, L.; Liang, Z.-X.; Grüber, G. Insights into biofilm dispersal regulation from the crystal structure of the PAS-GGDEF-EAL region of RbdA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2018, 200, e00515-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordery, C.; Craddock, J.; Malý, M.; Basavaraja, K.; Webb, J.S.; Walsh, M.A.; Tews, I. Control of phosphodiesterase activity in the regulator of biofilm dispersal RbdA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. RSC Chem. Biol. 2024, 5, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilers, K.; Kuok Hoong Yam, J.; Morton, R.; Mei Hui Yong, A.; Brizuela, J.; Hadjicharalambous, C.; Liu, X.; Givskov, M.; Rice, S.A.; Filloux, A. Phenotypic and integrated analysis of a comprehensive Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 library of mutants lacking cyclic-di-GMP-related genes. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 949597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, J.-H.; Hao, Y.; Nair, S.K. Structures of the PelD cyclic diguanylate effector involved in pellicle formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 30191–30204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remminghorst, U.; Rehm, B.H. Alg44, a unique protein required for alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 3883–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.D.; Boyd, C.D.; Sondermann, H.; O’Toole, G.A. A c-di-GMP effector system controls cell adhesion by inside-out signaling and surface protein cleavage. PLoS Biol. 2011, 9, e1000587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, R.B.; O’Donnell, J.P.; Sondermann, H. Coincidence detection and bi-directional transmembrane signaling control a bacterial second messenger receptor. Elife 2016, 5, e21848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybtke, M.; Berthelsen, J.; Yang, L.; Høiby, N.; Givskov, M.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. The LapG protein plays a role in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation by controlling the presence of the CdrA adhesin on the cell surface. Microbiologyopen 2015, 4, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbe, J.; Baker, A.E.; Euler, S.; O’Toole, G.A.; Maier, B. Role of cyclic di-GMP and exopolysaccharide in type IV pilus dynamics. J. Bacteriol. 2017, 199, e00859-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, S.S.; Lee, C.K.; Schmidt, W.C.; Wong, G.C.; O’Toole, G.A. Interaction between the type 4 pili machinery and a diguanylate cyclase fine-tune c-di-GMP levels during early biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2105566118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemke, A.C.; D’Amico, E.J.; Snell, E.C.; Torres, A.M.; Kasturiarachi, N.; Bomberger, J.M. Dispersal of epithelium-associated Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. mSphere 2020, 5, e00630-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, J.; Coenye, T. Biofilm dispersion: The key to biofilm eradication or opening Pandora’s box? Biofilm 2020, 2, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, T.E.; Eckartt, K.; Kakumanu, S.; Price-Whelan, A.; Dietrich, L.E.; Harrison, J.J. Sensory perception in bacterial cyclic diguanylate signal transduction. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e00433-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almblad, H.; Randall, T.E.; Liu, F.; Leblanc, K.; Groves, R.A.; Kittichotirat, W.; Winsor, G.L.; Fournier, N.; Au, E.; Groizeleau, J. Bacterial cyclic diguanylate signaling networks sense temperature. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.I.; Dolben, E.F.; Okegbe, C.; Harty, C.E.; Golub, Y.; Thao, S.; Ha, D.G.; Willger, S.D.; O’Toole, G.A.; Harwood, C.S. Candida albicans ethanol stimulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa WspR-controlled biofilm formation as part of a cyclic relationship involving phenazines. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.B.; Petrova, O.E.; Sauer, K. The phosphodiesterase DipA (PA5017) is essential for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm dispersion. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 2904–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Ahator, S.D.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Z.; Lin, Q.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.-H. Regulation of exopolysaccharide production by ProE, a cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlin, R.P.; Cathie, K.; Hall-Stoodley, L.; Cornelius, V.; Duignan, C.; Allan, R.N.; Fernandez, B.O.; Barraud, N.; Bruce, K.D.; Jefferies, J. Low-dose nitric oxide as targeted anti-biofilm adjunctive therapy to treat chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 2104–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, I.D.; Wang, Y.; Moradali, M.F.; Rehman, Z.U.; Rehm, B.H. Genetics and regulation of bacterial alginate production. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 2997–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M.J.; Nivens, D.E.; Weadge, J.T.; Howell, P.L. Biosynthesis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa extracellular polysaccharides, alginate, Pel, and Psl. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, L.; Yan, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Ke, X.; Shao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, S.; Dai, S.; Lu, J. A regulatory network involving Rpo, Gac and Rsm for nitrogen-fixing biofilm formation by Pseudomonas stutzeri. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscoso, J.A.; Jaeger, T.; Valentini, M.; Hui, K.; Jenal, U.; Filloux, A. The diguanylate cyclase SadC is a central player in Gac/Rsm-mediated biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 4081–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Ham, S.-Y.; Ryoo, H.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Yun, E.-T.; Park, H.-D.; Park, J.-H. Inhibiting bacterial biofilm formation by stimulating c-di-GMP regulation using citrus peel extract from Jeju Island. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 872, 162180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, N.; Ramirez Millan, M.; Caldara, M.; Rusconi, R.; Tarasova, Y.; Stocker, R.; Ribbeck, K. The extracellular matrix component Psl provides fast-acting antibiotic defense in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, L.K.; Storek, K.M.; Ledvina, H.E.; Coulon, C.; Marmont, L.S.; Sadovskaya, I.; Secor, P.R.; Tseng, B.S.; Scian, M.; Filloux, A. Pel is a cationic exopolysaccharide that cross-links extracellular DNA in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11353–11358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, H.; Charron-Mazenod, L.; Lewenza, S. Extracellular DNA chelates cations and induces antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.-C.; Nilsson, M.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Høiby, N.; Nielsen, T.E.; Givskov, M.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Extracellular DNA shields against aminoglycosides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 2352–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Sehar, S.; Koop, L.; Wong, Y.K.; Ahmed, S.; Siddiqui, K.S.; Manefield, M. Influence of calcium in extracellular DNA mediated bacterial aggregation and biofilm formation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.C.; Pritchard, M.F.; Ferguson, E.L.; Powell, K.A.; Patel, S.U.; Rye, P.D.; Sakellakou, S.-M.; Buurma, N.J.; Brilliant, C.D.; Copping, J.M. Targeted disruption of the extracellular polymeric network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms by alginate oligosaccharides. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2018, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamp, S.J.; Gjermansen, M.; Johansen, H.K.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Tolerance to the antimicrobial peptide colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms is linked to metabolically active cells, and depends on the pmr and mexAB-oprM genes. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 68, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Schurr, M.J.; Sauer, K. The MerR-like regulator BrlR confers biofilm tolerance by activating multidrug efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 3352–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, J.R.; Sauer, K. The MerR-like regulator BrlR impairs Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm tolerance to colistin by repressing PhoPQ. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 4678–4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, K.; Marques, C.N.; Petrova, O.E.; Sauer, K. Antimicrobial tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms is activated during an early developmental stage and requires the two-component hybrid SagS. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 4975–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horna, G.; López, M.; Guerra, H.; Saénz, Y.; Ruiz, J. Interplay between MexAB-OprM and MexEF-OprN in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Huang, J.; Xu, Z. Antibiotic influx and efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Regulation and therapeutic implications. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Xu, C.; Fang, R.; Cao, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, G.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, T. Resistance and heteroresistance to colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Wenzhou, China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00556-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampioni, G.; Pillai, C.R.; Longo, F.; Bondì, R.; Baldelli, V.; Messina, M.; Imperi, F.; Visca, P.; Leoni, L. Effect of efflux pump inhibition on Pseudomonas aeruginosa transcriptome and virulence. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt, M.; Limsuwannarot, S.P.; Bresee, C.; Poopalarajah, R.; Jorth, P. Pseudomonas aeruginosa mexR and mexEF antibiotic efflux pump variants exhibit increased virulence. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, J.; Price-Whelan, A.; Dietrich, L.E. Gradients and consequences of heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borriello, G.; Werner, E.; Roe, F.; Kim, A.M.; Ehrlich, G.D.; Stewart, P.S. Oxygen limitation contributes to antibiotic tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 2659–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiaterra, G.; Cedraro, N.; Vaiasicca, S.; Citterio, B.; Galeazzi, R.; Laudadio, E.; Mobbili, G.; Minnelli, C.; Bizzaro, D.; Biavasco, F. Role of tobramycin in the induction and maintenance of viable but non-culturable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in an in vitro biofilm model. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiaterra, G.; Cedraro, N.; Vaiasicca, S.; Citterio, B.; Frangipani, E.; Biavasco, F.; Vignaroli, C. Involvement of acquired tobramycin resistance in the shift to the viable but non-culturable state in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Song, Y.; Bartlam, M.; Wang, Y. Long-term effects of residual chlorine on Pseudomonas aeruginosa in simulated drinking water fed with low AOC medium. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P.S.; Franklin, M.J.; Williamson, K.S.; Folsom, J.P.; Boegli, L.; James, G.A. Contribution of stress responses to antibiotic tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 3838–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, S.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Gene transfer occurs with enhanced efficiency in biofilms and induces enhanced stabilisation of the biofilm structure. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2003, 14, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalder, T.; Top, E. Plasmid transfer in biofilms: A perspective on limitations and opportunities. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2016, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røder, H.L.; Trivedi, U.; Russel, J.; Kragh, K.N.; Herschend, J.; Thalsø-Madsen, I.; Tolker-Nielsen, T.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Burmølle, M.; Madsen, J.S. Biofilms can act as plasmid reserves in the absence of plasmid specific selection. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, G.A.; Ridenhour, B.J.; France, M.; Gliniewicz, K.; Millstein, J.; Settles, M.L.; Forney, L.J.; Stalder, T.; Top, E.M. Biofilms preserve the transmissibility of a multi-drug resistance plasmid. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzolato-Cezar, L.R.; Spira, B.; Machini, M.T. Bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems: Novel insights on toxin activation across populations and experimental shortcomings. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2023, 5, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Guo, Y.; Yao, J.; Tang, K.; Wang, X. Applications of toxin-antitoxin systems in synthetic biology. Eng. Microbiol. 2023, 3, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangla-Pélissier, G.; Roux, N.; Schmidt, V.; Chambonnier, G.; Ba, M.; Sebban-Kreuzer, C.; de Bentzmann, S.; Giraud, C.; Bordi, C. The horizontal transfer of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 ICE PAPI-1 is controlled by a transcriptional triad between TprA, NdpA2 and MvaT. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 10956–10974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.L.; Zavan, L.; Bitto, N.J.; Petrovski, S.; Hill, A.F.; Kaparakis-Liaskos, M. Planktonic and biofilm-derived Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane vesicles facilitate horizontal gene transfer of plasmid DNA. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e05179-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-del Valle, A.; León-Sampedro, R.; Rodríguez-Beltrán, J.; DelaFuente, J.; Hernández-García, M.; Ruiz-Garbajosa, P.; Cantón, R.; Peña-Miller, R.; San Millán, A. Variability of plasmid fitness effects contributes to plasmid persistence in bacterial communities. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieme, L.; Hartung, A.; Tramm, K.; Klinger-Strobel, M.; Jandt, K.D.; Makarewicz, O.; Pletz, M.W. MBEC versus MBIC: The lack of differentiation between biofilm reducing and inhibitory effects as a current problem in biofilm methodology. Biol. Proced. Online 2019, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenye, T. Biofilm antimicrobial susceptibility testing: Where are we and where could we be going? Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 36, e00024-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macia, M.; Rojo-Molinero, E.; Oliver, A. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing in biofilm-growing bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okae, Y.; Nishitani, K.; Sakamoto, A.; Kawai, T.; Tomizawa, T.; Saito, M.; Kuroda, Y.; Matsuda, S. Estimation of minimum biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC) on in vivo biofilm on orthopedic implants in a rodent femoral infection model. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 896978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentzer, M.; Wu, H.; Andersen, J.B.; Riedel, K.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Bagge, N.; Kumar, N.; Schembri, M.A.; Song, Z.; Kristoffersen, P. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 3803–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentzer, M.; Riedel, K.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Heydorn, A.; Andersen, J.B.; Parsek, M.R.; Rice, S.A.; Eberl, L.; Molin, S.; Høiby, N. Inhibition of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm bacteria by a halogenated furanone compound. Microbiology 2002, 148, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, T.H.; van Gennip, M.; Phipps, R.K.; Shanmugham, M.S.; Christensen, L.D.; Alhede, M.; Skindersoe, M.E.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Friedrich, K.; Uthe, F. Ajoene, a sulfur-rich molecule from garlic, inhibits genes controlled by quorum sensing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 2314–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, T.H.; Warming, A.N.; Vejborg, R.M.; Moscoso, J.A.; Stegger, M.; Lorenzen, F.; Rybtke, M.; Andersen, J.B.; Petersen, R.; Andersen, P.S. A broad range quorum sensing inhibitor working through sRNA inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naga, N.G.; Zaki, A.A.; El-Badan, D.E.; Rateb, H.S.; Ghanem, K.M.; Shaaban, M.I. Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing by methyl gallate from Mangifera indica. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Maldonado, O.; Lezcano-Domínguez, C.I.; Dávila-Aviña, J.; González, G.M.; Ríos-López, A.L. Methyl gallate attenuates virulence and decreases antibiotic resistance in extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 194, 106830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhove, M.; Jimenez, P.N.; Quax, W.J.; Dijkstra, B.W. The quorum-quenching N-acyl homoserine lactone acylase PvdQ is an Ntn-hydrolase with an unusual substrate-binding pocket. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utari, P.D.; Setroikromo, R.; Melgert, B.N.; Quax, W.J. PvdQ quorum quenching acylase attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence in a mouse model of pulmonary infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sompiyachoke, K.; Elias, M.H. Engineering quorum quenching acylases with improved kinetic and biochemical properties. Protein Sci. 2024, 33, e4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugayah, S.A.; Gerth, M.L. Engineering quorum quenching enzymes: Progress and perspectives. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019, 47, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.Z.; Reisch, C.R.; Prather, K.L.J. A robust CRISPR interference gene repression system in Pseudomonas. J. Bacteriol. 2018, 200, e00575-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.A.; Banta, A.B.; Ward, R.D.; Prasad, N.K.; Kwon, M.S.; Rosenberg, O.S.; Peters, J.M. Investigating Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene function during pathogenesis using mobile-CRISPRi. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Høyland-Kroghsbo, N.M.; Paczkowski, J.; Mukherjee, S.; Broniewski, J.; Westra, E.; Bondy-Denomy, J.; Bassler, B.L. Quorum sensing controls the Pseudomonas aeruginosa CRISPR-Cas adaptive immune system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dela Ahator, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.-H. The virulence factor regulator and quorum sensing regulate the type IF CRISPR-Cas mediated horizontal gene transfer in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 987656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, J.B.; Hultqvist, L.D.; Jansen, C.U.; Jakobsen, T.H.; Nilsson, M.; Rybtke, M.; Uhd, J.; Fritz, B.G.; Seifert, R.; Berthelsen, J. Identification of small molecules that interfere with c-di-GMP signaling and induce dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultqvist, L.D.; Andersen, J.B.; Nilsson, C.M.; Jansen, C.U.; Rybtke, M.; Jakobsen, T.H.; Nielsen, T.E.; Qvortrup, K.; Moser, C.; Graz, M. High efficacy treatment of murine Pseudomonas aeruginosa catheter-associated urinary tract infections using the c-di-GMP modulating anti-biofilm compound Disperazol in combination with ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e01481-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Heine, S.; Entian, M.; Sauer, K.; Frankenberg-Dinkel, N. NO-induced biofilm dispersion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by an MHYT domain-coupled phosphodiesterase. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 3531–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Oh, H.-S.; Ng, Y.C.B.; Tang, P.Y.P.; Barraud, N.; Rice, S.A. Nitric oxide-mediated induction of dispersal in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms is inhibited by flavohemoglobin production and is enhanced by imidazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01832-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, P.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Peng, L.; Fang, R.; Xiong, J.; Li, H.; Mei, C.; Gao, J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm dispersion by the mouse antimicrobial peptide CRAMP. Vet. Res. 2022, 53, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, B.A.; Tseng, B.S.; Baek, K.-H. Nanocomposites against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: Recent advances, challenges, and future prospects. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 282, 127656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Mao, Z.; Ran, F.; Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Chai, G.; Wang, J. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems to control bacterial-biofilm-associated lung infections. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.S.; Batista, J.G.; Rodrigues, M.Á.; Thipe, V.C.; Minarini, L.A.; Lopes, P.S.; Lugão, A.B. Advances in silver nanoparticles: A comprehensive review on their potential as antimicrobial agents and their mechanisms of action elucidated by proteomics. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1440065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamer, A.M.A.; El Maghraby, G.M.; Shafik, M.M.; Al-Madboly, L.A. Silver nanoparticle with potential antimicrobial and antibiofilm efficiency against multiple drug resistant, extensive drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haji, S.H.; Ganjo, A.R.; Faraj, T.A.; Fatah, M.H.; Smail, S.B. The enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm properties of titanium dioxide nanoparticles biosynthesized by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Momani, H.; Aolymat, I.; Ibrahim, L.; Albalawi, H.; Al Balawi, D.; Albiss, B.A.; Almasri, M.; Alghweiri, S. Low-dose zinc oxide nanoparticles trigger the growth and biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A hormetic response. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalvo, B.; Faraldos, M.; Bahamonde, A.; Rosal, R. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm efficacy of self-cleaning surfaces functionalized by TiO2 photocatalytic nanoparticles against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas putida. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 340, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maric, T.; Løvind, A.; Zhang, Z.; Geng, J.; Boisen, A. Near-infrared light-driven mesoporous SiO2/Au nanomotors for eradication of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2203018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetrick, E.M.; Shin, J.H.; Paul, H.S.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Anti-biofilm efficacy of nitric oxide-releasing silica nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2782–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colilla, M.; Vallet-Regí, M. Organically modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles against bacterial resistance. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 8788–8805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhariri, M.; Omri, A. Efficacy of liposomal bismuth-ethanedithiol-loaded tobramycin after intratracheal administration in rats with pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Vena, A.; Russo, A.; Peghin, M. Inhaled liposomal antimicrobial delivery in lung infections. Drugs 2020, 80, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallal Bashi, Y.H.; Mairs, R.; Murtadha, R.; Kett, V. Pulmonary delivery of antibiotics to the lungs: Current state and future prospects. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshaer, S.L.; Shaaban, M.I. Inhibition of quorum sensing and virulence factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by biologically synthesized gold and selenium nanoparticles. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afrasiabi, S.; Partoazar, A. Targeting bacterial biofilm-related genes with nanoparticle-based strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1387114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthi, V.K.; Fairfull-Smith, K.E.; Islam, N. Liposomal drug delivery strategies to eradicate bacterial biofilms: Challenges, recent advances, and future perspectives. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 655, 124046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topka-Bielecka, G.; Dydecka, A.; Necel, A.; Bloch, S.; Nejman-Faleńczyk, B.; Węgrzyn, G.; Węgrzyn, A. Bacteriophage-derived depolymerases against bacterial biofilm. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Bai, C.; Leung, S.S.Y. Translating bacteriophage-derived depolymerases into antibacterial therapeutics: Challenges and prospects. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisson, H.M.; Jackson, S.A.; Fagerlund, R.D.; Warring, S.L.; Fineran, P.C. Gram-negative endolysins: Overcoming the outer membrane obstacle. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2024, 78, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, J.; Zhou, J.; Yu, R.; Zhang, C. Design SMAP29-LysPA26 as a highly efficient artilysin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa with bactericidal and antibiofilm activity. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e00546-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Soir, S.; Parée, H.; Kamarudin, N.H.N.; Wagemans, J.; Lavigne, R.; Braem, A.; Merabishvili, M.; De Vos, D.; Pirnay, J.-P.; Van Bambeke, F. Exploiting phage-antibiotic synergies to disrupt Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms in the context of orthopedic infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e03219-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, P.; Loh, B.; Nachimuthu, R.; Leptihn, S. Phage-antibiotic combinations to control Pseudomonas aeruginosa–Candida two-species biofilms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-C.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Lin, N.-T. Phage–Antibiotic Synergy Enhances Biofilm Eradication and Survival in a Zebrafish Model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunisch, F.; Campobasso, C.; Wagemans, J.; Yildirim, S.; Chan, B.K.; Schaudinn, C.; Lavigne, R.; Turner, P.E.; Raschke, M.J.; Trampuz, A. Targeting Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm with an evolutionary trained bacteriophage cocktail exploiting phage resistance trade-offs. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Su, T.; Wu, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Zhao, T.; Jin, Z.; Du, W.; Zhu, M.-J.; Chua, S.L. PslG, a self-produced glycosyl hydrolase, triggers biofilm disassembly by disrupting exopolysaccharide matrix. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 1352–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.; Whitfield, G.B.; Hill, P.J.; Little, D.J.; Pestrak, M.J.; Robinson, H.; Wozniak, D.J.; Howell, P.L. Characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa glycoside hydrolase PslG reveals that its levels are critical for Psl polysaccharide biosynthesis and biofilm formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 28374–28387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.; He, J.; Li, N.; Liu, S.; Xu, S.; Gu, L. A rational designed PslG with normal biofilm hydrolysis and enhanced resistance to trypsin-like protease digestion. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, Z.; Khoshbayan, A.; Taati Moghadam, M.; Farahani, I.; Jazireian, P.; Shariati, A. Bacteriophage therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: A review. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.O.; Yu, X.Q.; Robbie, G.J.; Wu, Y.; Shoemaker, K.; Yu, L.; DiGiandomenico, A.; Keller, A.E.; Anude, C.; Hernandez-Illas, M. Phase 1 study of MEDI3902, an investigational anti–Pseudomonas aeruginosa PcrV and Psl bispecific human monoclonal antibody, in healthy adults. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 629.e1–629.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastre, J.; François, B.; Bourgeois, M.; Komnos, A.; Ferrer, R.; Rahav, G.; De Schryver, N.; Lepape, A.; Koksal, I.; Luyt, C.-E. Safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of gremubamab (MEDI3902), an anti-Pseudomonas aeruginosa bispecific human monoclonal antibody, in P. aeruginosa-colonised, mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients: A randomised controlled trial. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.B.; Gilmour, A.; Kehl, M.; Tabor, D.E.; Keller, A.E.; Warrener, P.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Rosengren, S.; Crichton, M.L.; McIntosh, E. A bispecific monoclonal antibody targeting Psl and PcrV enhances neutrophil-mediated killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with bronchiectasis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killough, M.; Rodgers, A.M.; Ingram, R.J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Recent advances in vaccine development. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamarina-Fernández, R.; Fuentes-Valverde, V.; Silva-Rodríguez, A.; García, P.; Moscoso, M.; Bou, G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Vaccine Development: Lessons, Challenges, and Future Innovations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.; Zanjani, L.S. Immunization against Pseudomonas aeruginosa using Alg-PLGA nano-vaccine. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2021, 24, 476. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.A.; Lee, S.-J.; Park, N.-H.; Mechesso, A.F.; Birhanu, B.T.; Kang, J.; Reza, M.A.; Suh, J.-W.; Park, S.-C. Impact of phenolic compounds in the acyl homoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing regulatory pathways. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sio, C.F.; Otten, L.G.; Cool, R.H.; Diggle, S.P.; Braun, P.G.; Bos, R.; Daykin, M.; Cámara, M.; Williams, P.; Quax, W.J. Quorum quenching by an N-acyl-homoserine lactone acylase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.W.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, J.-S. Targeted genome engineering in human cells with the Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraud, N.; Hassett, D.J.; Hwang, S.-H.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S.; Webb, J.S. Involvement of nitric oxide in biofilm dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 7344–7353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakal, T.C.; Kumar, A.; Majumdar, R.S.; Yadav, V. Mechanistic basis of antimicrobial actions of silver nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghunath, A.; Perumal, E. Metal oxide nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents: A promise for the future. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 49, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhang, D. Potential of phage depolymerase for the treatment of bacterial biofilms. Virulence 2023, 14, 2273567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, P.; Loh, B.; Turner, D.; Tamizhselvi, R.; Mathankumar, M.; Elangovan, N.; Nachimuthu, R.; Leptihn, S. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the biofilm-degrading Pseudomonas phage Motto, as a candidate for phage therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1344962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgeya, K.D.; Subedi, D.; Kumar, N.; Willcox, M. The Ability of Bacteriophages to Reduce Biofilms Produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Corneal Infections. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabor, D.; Oganesyan, V.; Keller, A.; Yu, L.; McLaughlin, R.; Song, E.; Warrener, P.; Rosenthal, K.; Esser, M.; Qi, Y. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PcrV and Psl, the molecular targets of bispecific antibody MEDI3902, are conserved among diverse global clinical isolates. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichhardt, C.; Parsek, M.R. Confocal laser scanning microscopy for analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm architecture and matrix localization. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhade, S.; Kaushik, K.S. Tools of the trade: Image analysis programs for confocal laser-scanning microscopy studies of biofilms and considerations for their use by experimental researchers. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 20163–20177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountcastle, S.E.; Vyas, N.; Villapun, V.M.; Cox, S.C.; Jabbari, S.; Sammons, R.L.; Shelton, R.M.; Walmsley, A.D.; Kuehne, S.A. Biofilm viability checker: An open-source tool for automated biofilm viability analysis from confocal microscopy images. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demidov, V.V.; Jackson, O.P.; Demidova, N.; Gunn, J.R.; Gitajn, I.L.; Elliott, J.T. Integrating optical coherence tomography and bioluminescence with predictive modeling for quantitative assessment of methicillin-resistant S. aureus biofilms. J. Biomed. Opt. 2025, 30, S34111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine, B.C.; Dogan, A.B.; Sobol, W.M. Recent Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) Innovations for Increased Accessibility and Remote Surveillance. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, B.; Zorin, I.; Duswald, K.; Karl, V.; Brouczek, D.; Eichelseder, J.; Schwentenwein, M. Mid-infrared optical coherence tomography and machine learning for inspection of 3D-printed ceramics at the micron scale. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1441812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, C.; Marks, D.; Schlachter, S.; Luo, W.; Boppart, S.A. High-resolution three-dimensional imaging of biofilm development using optical coherence tomography. J. Biomed. Opt. 2006, 11, 034001. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J.; Wang, C.; Rozenbaum, R.T.; Gusnaniar, N.; de Jong, E.D.; Woudstra, W.; Geertsema-Doornbusch, G.I.; Atema-Smit, J.; Sjollema, J.; Ren, Y. Bacterial density and biofilm structure determined by optical coherence tomography. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haval, M.; Unakal, C.; Ghagane, S.C.; Pandit, B.R.; Daniel, E.; Siewdass, P.; Ekimeri, K.; Rajamanickam, V.; Justiz-Vaillant, A.; Lootawan, K.-A.A. Biofilms Exposed: Innovative Imaging and Therapeutic Platforms for Persistent Infections. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polisetti, S.; Baig, N.F.; Morales-Soto, N.; Shrout, J.D.; Bohn, P.W. Spatial mapping of pyocyanin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacterial communities using surface enhanced Raman scattering. Appl. Spectrosc. 2017, 71, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelon, G.; Montes-García, V.; Perez-Juste, J.; Pastoriza-Santos, I. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering spectroscopy for label-free analysis of P. aeruginosa quorum sensing. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J. Spatiotemporal Mapping of Quinolone and Phenazine Secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms by Confocal Raman Imaging. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kotowska, A.M.; Zhang, J.; Carabelli, A.; Watts, J.; Aylott, J.W.; Gilmore, I.S.; Williams, P.; Scurr, D.J.; Alexander, M.R. Toward comprehensive analysis of the 3D chemistry of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 18287–18294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D. Recent advances of Raman spectroscopy for the analysis of bacteria. Anal. Sci. Adv. 2023, 4, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Weaver, A.A.; Baek, S.; Jia, J.; Shrout, J.D.; Bohn, P.W. Depth distributions of signaling molecules in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms mapped by confocal Raman microscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 204201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.; Kwon, S.-R.; Fu, K.; Morales-Soto, N.; Shrout, J.D.; Bohn, P.W. Electrochemical surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy of pyocyanin secreted by Pseudomonas aeruginosa communities. Langmuir 2019, 35, 7043–7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyuko, R.N.; Lanni, E.J.; Driscoll, C.M.; Shrout, J.D.; Sweedler, J.V.; Bohn, P.W. Spatial organization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms probed by combined matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry and confocal Raman microscopy. Analyst 2014, 139, 5700–5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanni, E.J.; Masyuko, R.N.; Driscoll, C.M.; Aerts, J.T.; Shrout, J.D.; Bohn, P.W.; Sweedler, J.V. MALDI-guided SIMS: Multiscale imaging of metabolites in bacterial biofilms. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 9139–9145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xie, P.; Xie, C.; Chen, Y.; Banaei, N.; Ren, K.; Cai, Z. High-resolution 3D spatial distribution of complex microbial colonies revealed by mass spectrometry imaging. J. Adv. Res. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Beenker, W.A.; van Son, G.J.; Begthel, H.; Amatngalim, G.D.; Beekman, J.M.; Clevers, H.; den Hertog, J. Dual RNA sequencing of a co-culture model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and human 2D upper airway organoids. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Beenker, W.A.; van Son, G.J.; Begthel, H.; Amatngalim, G.D.; Beekman, J.M.; Clevers, H.; den Hertog, J. Establishment and characterization of a new Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection model using 2D airway organoids and dual RNA sequencing. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, N.C.; Rendón, J.M.; López, J.J.G.; Tizzano, S.G.; Gómez, M.T.M.; Burgas, M.T. Time-resolved dual transcriptomics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation in cystic fibrosis. Biofilm 2025, 10, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengge, R. High-specificity local and global c-di-GMP signaling. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katharios-Lanwermeyer, S.; Whitfield, G.B.; Howell, P.L.; O’Toole, G.A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases RmcA and MorA to regulate biofilm maintenance. mBio 2021, 12, e03384-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, R.A.; Volke, D.C.; Tenaglia, A.H.; Tribelli, P.M.; Nikel, P.I.; Smania, A.M. Genetic Dissection of Cyclic di-GMP Signalling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa via Systematic Diguanylate Cyclase Disruption. Microb. Biotechnol. 2025, 18, e70137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noirot-Gros, M.-F.; Forrester, S.; Malato, G.; Larsen, P.E.; Noirot, P. CRISPR interference to interrogate genes that control biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasenina, A.; Fu, Y.; O’Toole, G.A.; Mucha, P.J. Local control: A hub-based model for the c-di-GMP network. Msphere 2024, 9, e00178-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junkermeier, E.H.; Hengge, R. Local signaling enhances output specificity of bacterial c-di-GMP signaling networks. Microlife 2023, 4, uqad026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, K.; de Vogel, C.P.; Klaassen, C.; Luider, T.; Zeneyedpour, L.; Mason-Slingerland, B.C.; Vos, M.C.; Bruno, M.; Bexkens, M.L.; Severin, J.A. Proteomic identification of Pa2146 as a biofilm marker of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on endoscope channel material. SSRN Electron. J. 2025, 10, 5288165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuik, C.; van Hoogstraten, S.W.; Arts, J.J.; Honing, M.; Cillero-Pastor, B. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging for quorum sensing. AMB Express 2024, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, Y.T.; Lau, D.; Mittal, P.; Hoffmann, P. Mini review: Highlight of recent advances and applications of MALDI mass spectrometry imaging in 2024. Anal. Sci. Adv. 2025, 6, e70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, S.; Ibrahim, H.; Yaseen, M.U.; Kulsoom, F.; Cinti, S.; Sher, M. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy-based sensing of biofilms: A comprehensive review. Biosensors 2023, 13, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghighian, N.; Kataky, R. Advances in electrochemical detection of bacterial biofilm metabolites. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2024, 46, 101486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, O.J.; Wang, Y.; Ahmed, A. Making waves: Transforming biofilm-based wastewater treatment using machine learning-driven real-time monitoring. Water Res. 2025, 287, 124491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouhagger, A.; Celiešiūtė-Germanienė, R.; Bakute, N.; Stirke, A.; Melo, W.C. Electrochemical biosensors on microfluidic chips as promising tools to study microbial biofilms: A review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1419570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Cabra, N.; López-Martínez, M.J.; Arévalo-Jaimes, B.V.; Martin-Gómez, M.T.; Samitier, J.; Torrents, E. A new BiofilmChip device for testing biofilm formation and antibiotic susceptibility. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plebani, R.; Potla, R.; Soong, M.; Bai, H.; Izadifar, Z.; Jiang, A.; Travis, R.N.; Belgur, C.; Dinis, A.; Cartwright, M.J. Modeling pulmonary cystic fibrosis in a human lung airway-on-a-chip. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2022, 21, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, A.A.; Shrout, J.D. Use of analytical strategies to understand spatial chemical variation in bacterial surface communities. J. Bacteriol. 2025, 207, e00402-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Dabburu, G.R.; Samanta, B.; Singhal, N.; Kumar, M. An explainable machine learning pipeline for prediction of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Bioinform. Adv. 2025, 5, vbaf190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergauwe, F.; De Waele, G.; Sass, A.; Highmore, C.; Hanrahan, N.; Cook, Y.; Lichtenberg, M.; Cnockaert, M.; Vandamme, P.; Mahajan, S. Harnessing machine learning to predict antibiotic susceptibility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. bioRxiv 2025, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, H.; Khan, M.N.; Khan, S.; Shafiq, M.; Fang, W.; Khan, R.U.; Rahman, M.U.; Li, X.; Lv, Q.-L.; Xu, B. The role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in predicting and combating antimicrobial resistance. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, W.H.; Rice, S.A. Recent developments in nitric oxide donors and delivery for antimicrobial and anti-biofilm applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 10993-1:2018; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 1: Evaluation and Testing Within a Risk Management Process. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/68936.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ISO 10993-5:2009; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. Available online: https://www.x-cellr8.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/CT-060_01-07_20-ISO-Cytotoxicity.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- FDA. Use of International Standard ISO 10993-1, “Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 1: Evaluation and Testing Within a Risk Management Process”: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff; U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/142959/download (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ISO/TR 10993-22:2017; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 22: Guidance on Nanomaterials. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/65918.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Gruber, S.; Nickel, A. Toxic or not toxic? The specifications of the standard ISO 10993-5 are not explicit enough to yield comparable results in the cytotoxicity assessment of an identical medical device. Front. Med. Technol. 2023, 5, 1195529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/TR 10993-55:2023; Biocompatibility Assessment of Medical Devices. eFOR Group: Paris, France, 2023. Available online: https://efor-group.com/en/biocompatibility-assessment-of-md-iso-tr-10993-552023/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Kanďárová, H.; Pôbiš, P. The “Big Three” in biocompatibility testing of medical devices: Implementation of alternatives to animal experimentation—Are we there yet? Front. Toxicol. 2024, 5, 1337468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-18:2020; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 18: Chemical Characterization of Medical Device Materials Within a Risk Management Process. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/64750.html (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Kalia, V.C.; Wood, T.K.; Kumar, P. Evolution of resistance to quorum-sensing inhibitors. Microb. Ecol. 2014, 68, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiga, A.; Ampomah-Wireko, M.; Li, H.; Fan, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhen, H.; Kpekura, S.; Wu, C. Multidrug-resistant bacteria quorum-sensing inhibitors: A particular focus on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 281, 117008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetta, H.F.; Ramadan, Y.N.; Rashed, Z.I.; Alharbi, A.A.; Alsharef, S.; Alkindy, T.T.; Alkhamali, A.; Albalawi, A.S.; Battah, B.; Donadu, M.G. Quorum sensing inhibitors: An alternative strategy to win the battle against multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria. Molecules 2024, 29, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.K.; Chen, Q.; Echterhof, A.; Pennetzdorfer, N.; McBride, R.C.; Banaei, N.; Burgener, E.B.; Milla, C.E.; Bollyky, P.L. A blueprint for broadly effective bacteriophage-antibiotic cocktails against bacterial infections. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.-M.; Zhang, Y.-D.; Yang, L. NO donors and NO delivery methods for controlling biofilms in chronic lung infections. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 3931–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Inhaled Sodium Nitrite As an Antimicrobial for Cystic Fibrosis (Identifier: NCT02694393); U.S. National Library of Medicine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02694393 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Debast, S.; van den Bos-Kromhout, M.; de Vries-van Rossum, S.; Abma-Blatter, S.; Notermans, D.; Kluytmans, J.; Immeker, B.; Zuur, J.; Hijmering, M.; Bergwerff, A. Aquatic reservoir-associated outbreaks of multidrug-resistant bacteria: A hospital outbreak report of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in perspective from the Dutch national surveillance databases. J. Hosp. Infect. 2025, 162, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querin, B.; Danjean, M.; Jolivet, S.; Couturier, J.; Oubbéa, S.; Jouans, C.; Lazare, C.; Montagne, T.; Chamming’s, A.; Luce, S. Protracted outbreaks of VIM-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a surgical intensive care unit in France, January 2018 to June 2024. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2025, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, A.; Kieninger, B.; Fritsch, J.; Caplunik-Pratsch, A.; Blaas, S.; Ochmann, M.; Pfeifer, M.; Hartl, J.; Holzmann, T.; Schneider-Brachert, W. Whole-genome sequencing reveals two prolonged simultaneous outbreaks involving Pseudomonas aeruginosa high-risk strains ST111 and ST235 with resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds. J. Hosp. Infect. 2024, 145, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]