Non-Targeted Screening Method for Detecting Temporal Shifts in Spectral Patterns of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Post Hoc Description of Peak Features

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Spectral Dataset

2.2. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) Model Training and Decision Scores

2.3. Performance Characteristics

2.4. Significance Testing and t-Values

2.5. Feature Extraction Using Grad-CAM

2.6. Peak Features Changing over Time

3. Results

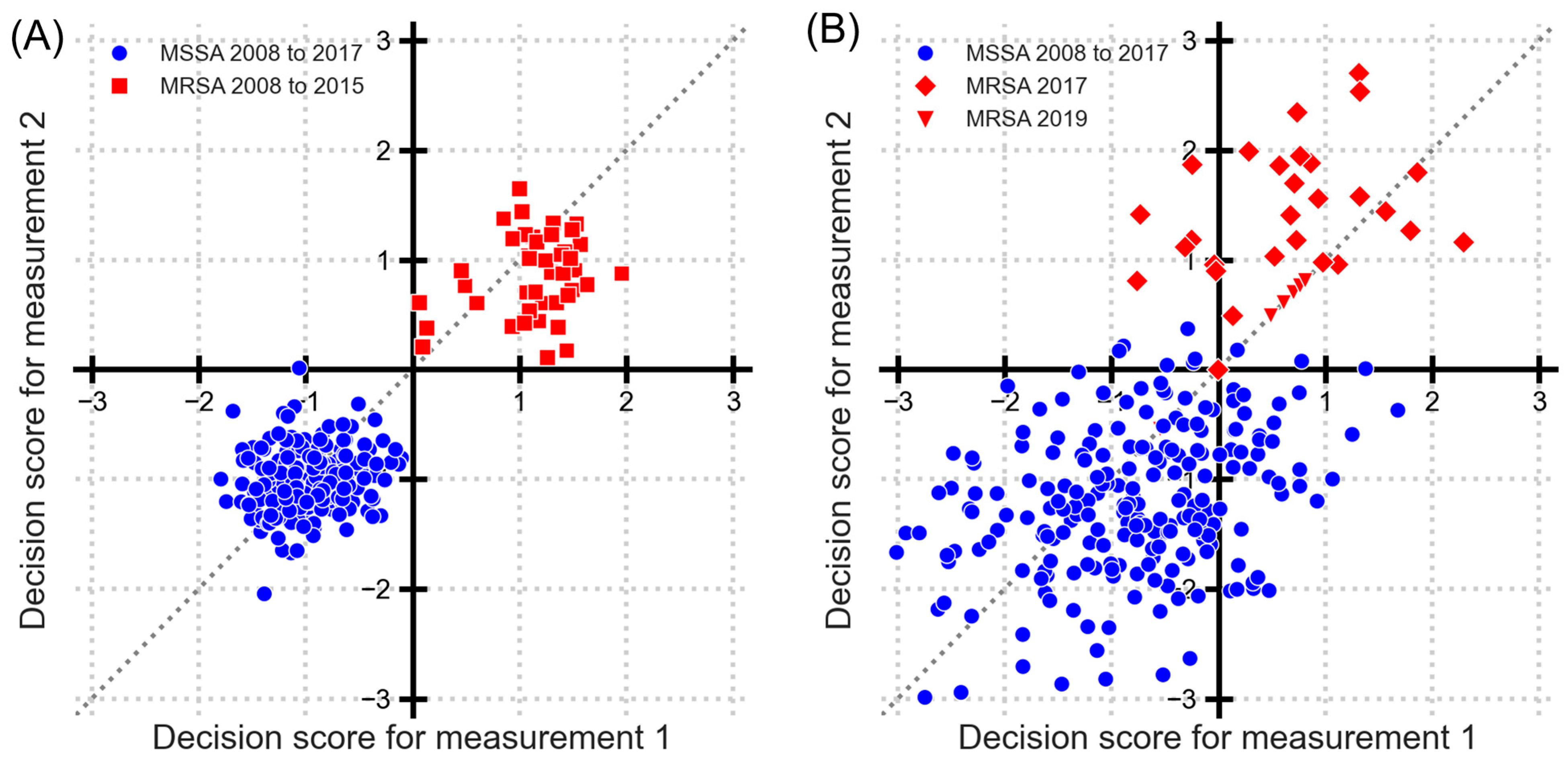

3.1. Identifying Temporal Changes Using Classification Decision Scores for MRSA and MSSA

3.2. Sequential Significance Testing of Decision Scores

3.3. Finding Breaks by Year-Wise Training

3.4. Tracking Features over Time

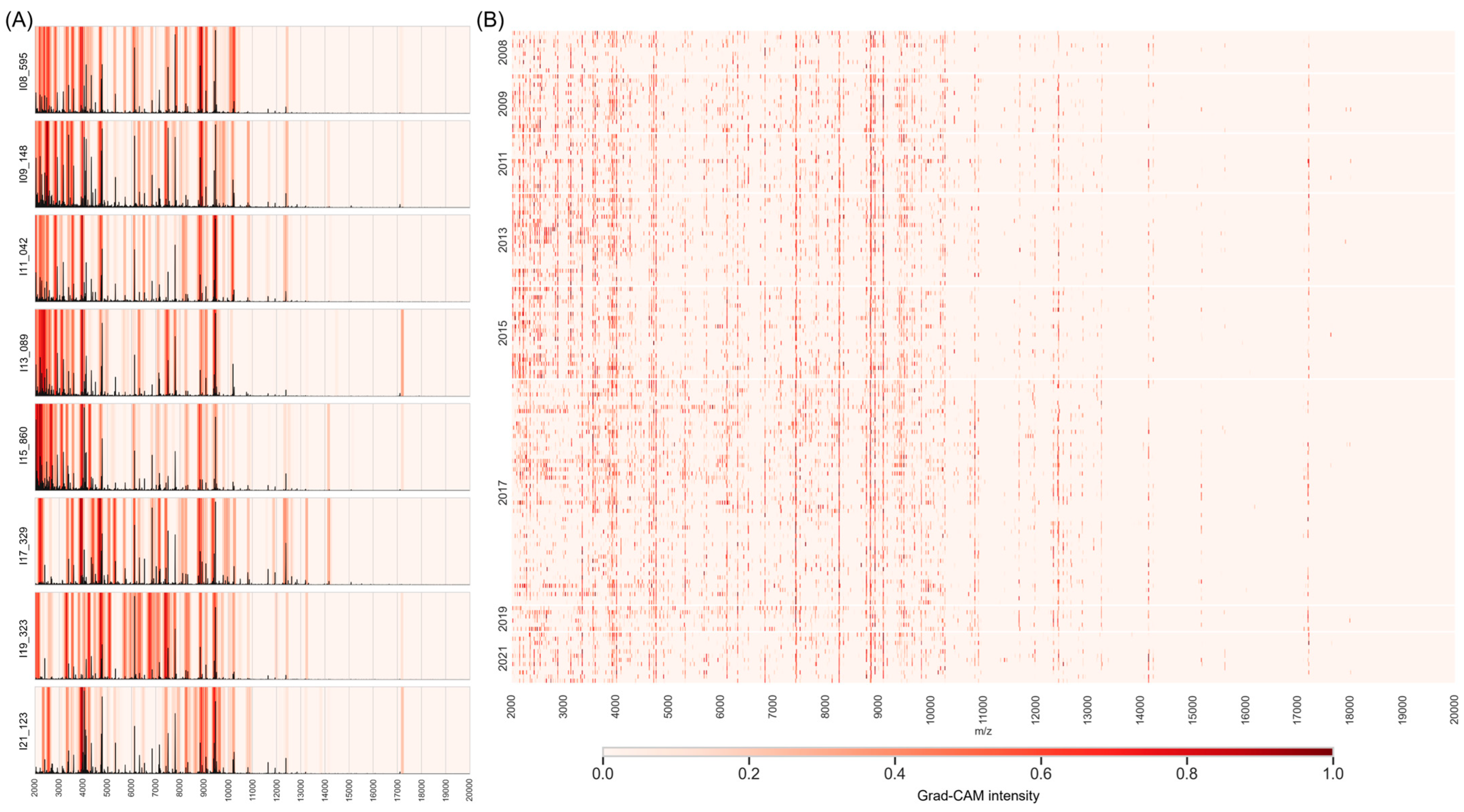

3.4.1. Feature Extraction Heatmaps

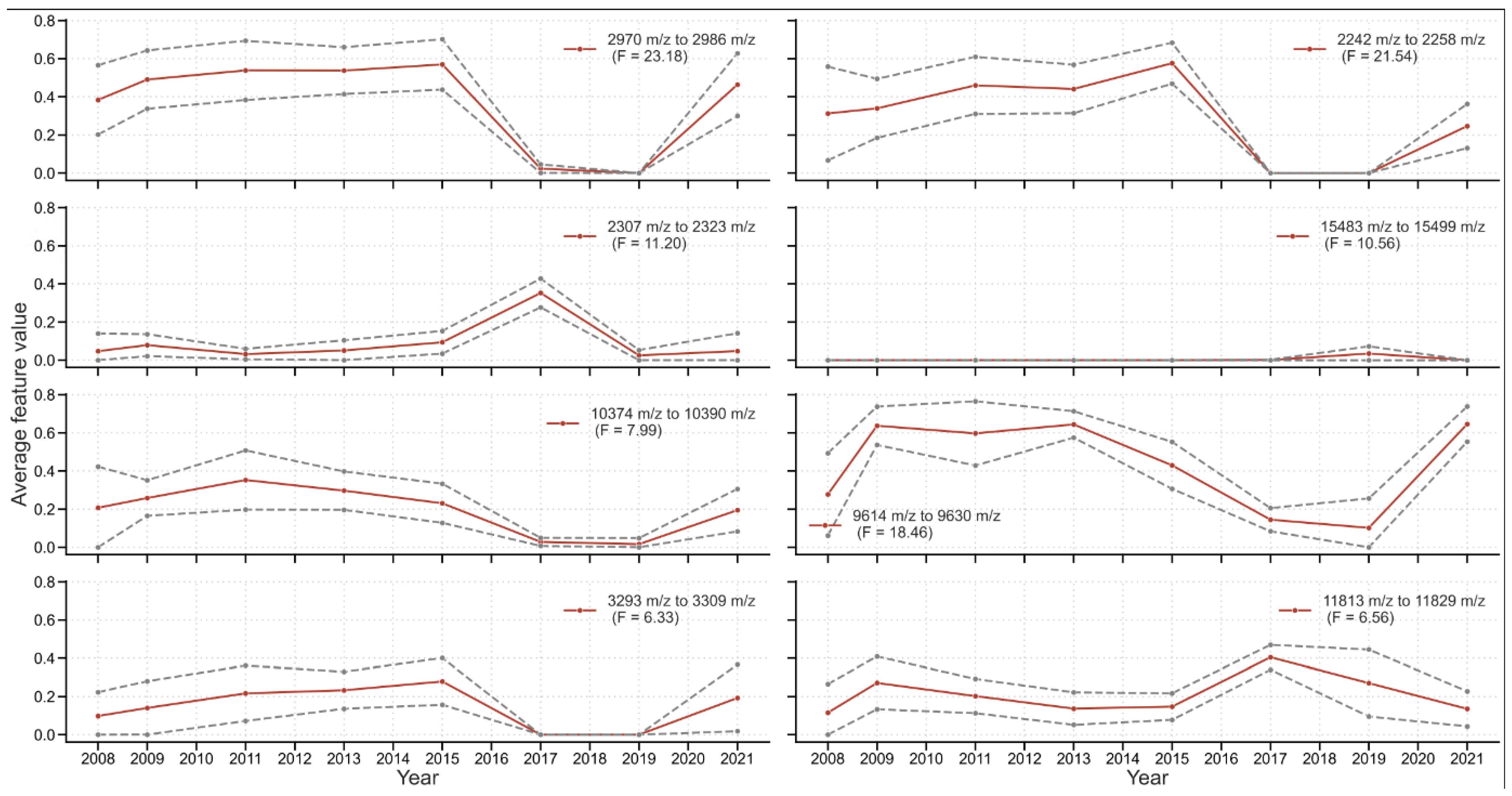

3.4.2. Detecting Specific Peaks Sensitive to Temporal Changes

3.5. Classification Performance Based on Different Time Periods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolters, M.; Rohde, H.; Maier, T.; Belmar-Campos, C.; Franke, G.; Scherpe, S.; Aepfelbacher, M.; Christner, M. MALDI-TOF MS Fingerprinting Allows for Discrimination of Major Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Lineages. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 301, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sancho, M.; Vela, A.I.; Horcajo, P.; Ugarte-Ruiz, M.; Domínguez, L.; Fernández-Garayzábal, J.F.; De La Fuente, R. Rapid Differentiation of Staphylococcus aureus Subspecies Based on MALDI-TOF MS Profiles. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2018, 30, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Złoch, M.; Pomastowski, P.; Maślak, E.; Monedeiro, F.; Buszewski, B. Study on Molecular Profiles of Staphylococcus Aureus Strains: Spectrometric Approach. Molecules 2020, 25, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichani, K.; Uhlig, S.; Stoyke, M.; Kemmlein, S.; Ulberth, F.; Haase, I.; Döring, M.; Walch, S.G.; Gowik, P. Essential Terminology and Considerations for Validation of Non-Targeted Methods. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Garden, R.W.; Sweedler, J.V. Single-Cell MALDI: A New Tool for Direct Peptide Profiling. Trends Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Luo, R.; Tang, S.; Song, H.; Chen, X. Machine Learning in Predicting Antimicrobial Resistance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2022, 60, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, C.V.; Jutzeler, C.R.; Borgwardt, K. Machine Learning for Microbial Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing on MALDI-TOF Mass Spectra: A Systematic Review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1310–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, D.; Park, J.S.; Kim, K.; Seo, D.; Kim, D.-C.; Kim, J.-S.; Park, J.-M. Rapid Screening of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Using MALDI-TOF MS and Machine Learning: A Randomized, Multicenter Study. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 15667–15675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touaitia, R.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Touati, A.; Idres, T. Staphylococcus Aureus in Bovine Mastitis: A Narrative Review of Prevalence, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Advances in Detection Strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvelo Benz, N.; Miranda, L.; Chen, D.; Sattler, J.; Borgwardt, K. Conformal Prediction with Knowledge Graphs for Reliable Antimicrobial Resistance Detection with MALDI-TOF Mass Spectra. J. Comput. Biol. 2025, 15578666251396558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauget, M.; Valot, B.; Bertrand, X.; Hocquet, D. Can MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry Reasonably Type Bacteria? Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, G.F.D.S.; Barcellos Filho, F.N.; Wichmann, R.M.; Da Silva Junior, F.C.; Chiavegatto Filho, A.D.P. Strategies for Detecting and Mitigating Dataset Shift in Machine Learning for Health Predictions: A Systematic Review. J. Biomed. Inform. 2025, 170, 104902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbehiry, A.; Marzouk, E. From Farm to Fork: Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacterial Pathogens in Livestock Production and the Food Chain. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbehiry, A.; Abalkhail, A. Spectral Precision: Recent Advances in Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry for Pathogen Detection and Resistance Profiling. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østergaard, C.; Hansen, S.G.K.; Møller, J.K. Rapid First-Line Discrimination of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Strains Using MALDI-TOF MS. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 305, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Tien, N.; Liu, Y.-C.; Cho, D.-Y.; Chen, J.-W.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chao, H.-J.; Chen, C.-J. Rapid Identification of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Using MALDI-TOF MS and Machine Learning from over 20,000 Clinical Isolates. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00483-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-M.; Kim, I.; Chung, S.H.; Chung, Y.; Han, M.; Kim, J.S. Rapid Discrimination of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus by MALDI-TOF MS. Pathogens 2019, 8, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskova, V.; Chudejova, K.; Sramkova, A.; Kraftova, L.; Jakubu, V.; Petinaki, E.A.; Zemlickova, H.; Neradova, K.; Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Hrabak, J. Insufficient Repeatability and Reproducibility of MALDI-TOF MS-Based Identification of MRSA. Folia Microbiol. 2020, 65, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasch, P.; Fleige, C.; Stämmler, M.; Layer, F.; Nübel, U.; Witte, W.; Werner, G. Insufficient Discriminatory Power of MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry for Typing of Enterococcus Faecium and Staphylococcus Aureus Isolates. J. Microbiol. Methods 2014, 100, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasch, P.; Wahab, T.; Weil, S.; Pályi, B.; Tomaso, H.; Zange, S.; Kiland Granerud, B.; Drevinek, M.; Kokotovic, B.; Wittwer, M.; et al. Identification of Highly Pathogenic Microorganisms by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization—Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry: Results of an Interlaboratory Ring Trial. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 2632–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vestergaard, M.; Frees, D.; Ingmer, H. Antibiotic Resistance and the MRSA Problem. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viboud, G.; Asaro, H.; Huang, M.B. Use of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) to Detect Antibiotic Resistance in Bacteria: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2024, 161, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesmann, N.; Enders, D.; Westendorf, A.; Koch, R.; Schaumburg, F. Prediction of Antimicrobial Resistance from MALDI-TOF Mass Spectra Using Machine Learning: A Validation Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2025, 63, e01186-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, E.P.; Gopal, J.; Muthu, M. Analytical Techniques for Assessing Antimicrobial Resistance: Conventional Solutions, Contemporary Problems and Futuristic Outlooks. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 178, 117843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Weig, M.; Noll, C.; Bader, O.; Hauschild, A.-C. Effect of Data Heterogeneity in Clinical MALDI-TOF Mass Spectra Profiles on Direct Antimicrobial Resistance Prediction Through Machine Learning. bioXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kull, M.; Flach, P. Patterns of Dataset Shift. 2014. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Patterns-of-dataset-shift-Kull-Flach/aa49eb379d55fd4c923f47efcd61b2090f58e54f (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Singh, H.; Ghassemi, M.; Joshi, S. “Why Did the Model Fail?”: Attributing Model Performance Changes to Distribution Shifts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2210.10769. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Torres, J.G.; Raeder, T.; Alaiz-Rodríguez, R.; Chawla, N.V.; Herrera, F. A Unifying View on Dataset Shift in Classification. Pattern Recognit. 2012, 45, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, J.; Žliobaitė, I.; Bifet, A.; Pechenizkiy, M.; Bouchachia, A. A Survey on Concept Drift Adaptation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2014, 46, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-Cam: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, G.; Fleige, C.; Feßler, A.T.; Timke, M.; Kostrzewa, M.; Zischka, M.; Peters, T.; Kaspar, H.; Schwarz, S. Improved Identification Including MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Group D Streptococci from Bovine Mastitis and Subsequent Molecular Characterization of Corresponding Enterococcus Faecalis and Enterococcus Faecium Isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 160, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. keras, GitHub. 2015. Available online: https://github.com/keras-team/keras (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Abadi, M.; Barham, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; Ghemawat, S.; Irving, G.; Isard, M.; et al. TensorFlow: A System for Large-Scale Machine Learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.08695. [Google Scholar]

- Nichani, K.; Uhlig, S.; Colson, B.; Hettwer, K.; Simon, K.; Bönick, J.; Uhlig, C.; Kemmlein, S.; Stoyke, M.; Gowik, P.; et al. Development of Non-Targeted Mass Spectrometry Method for Distinguishing Spelt and Wheat. Foods 2022, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vabalas, A.; Gowen, E.; Poliakoff, E.; Casson, A.J. Machine Learning Algorithm Validation with a Limited Sample Size. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlig, S.; Nichani, K.; Stoyke, M.; Gowik, P. Validation of Binary Non-Targeted Methods: Mathematical Framework and Experimental Designs. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlig, S.; Nichani, K.; Colson, B.; Hettwer, K.; Simon, K.; Uhlig, C.; Stoyke, M.; Steinacker, U.; Becker, R.; Gowik, P. Performance Characteristics and Criteria for Non-Targeted Methods. In Proceedings of the Eurachem Workshop, Tartu, Estonia, 20–21 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 5725-2:2025; Accuracy (Trueness and Precision) of Measurement Methods and Results—Part 2: Basic Method for the Determination of Repeatability and Reproducibility of a Standard Measurement Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Draelos, R.L.; Carin, L. Use HiResCAM Instead of Grad-CAM for Faithful Explanations of Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.08891. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler, M.D.; Fergus, R. Visualizing and Understanding Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Part I 13. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 818–833. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, H.N.; Rajakaruna, L.; Ball, G.; Misra, R.; Al-Shahib, A.; Fang, M.; Gharbia, S.E. Tracing the Transition of Methicillin Resistance in Sub-Populations of Staphylococcus Aureus, Using SELDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry and Artificial Neural Network Analysis. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 34, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Narro, D.; Ferri, P.; Gutiérrez-Sacristán, A.; García-Gómez, J.M.; Sáez, C. Unsupervised Characterization of Temporal Dataset Shifts as an Early Indicator of AI Performance Variations: Evaluation Study Using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV Dataset. JMIR Med. Inform. 2025, 13, e78309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-H.; Chung, H.-Y.; Jian, M.-J.; Chang, C.-K.; Perng, C.-L.; Chang, F.-Y.; Chen, C.-W.; Shang, H.-S. Accelerating Antimicrobial Stewardship: An AI-CDSS Approach to Combating Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens in the Era of Increasing Resistance. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 574, 120336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greutmann, M.; Borgwardt, K.; Brüningk, S.; Franzeck, F.; Giske, C.G.; Green, A.G.; Guerrero-López, A.; Ip, M.; Jutzeler, C.; Kahles, A.; et al. ESCMID Workshop: Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Medical Microbiology Diagnostics. Microbes Infect. 2025, 105562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nichani, K.; Uhlig, S.; San Martin, V.; Hettwer, K.; Frost, K.; Steinacker, U.; Kaspar, H.; Gowik, P.; Kemmlein, S. Non-Targeted Screening Method for Detecting Temporal Shifts in Spectral Patterns of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Post Hoc Description of Peak Features. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010104

Nichani K, Uhlig S, San Martin V, Hettwer K, Frost K, Steinacker U, Kaspar H, Gowik P, Kemmlein S. Non-Targeted Screening Method for Detecting Temporal Shifts in Spectral Patterns of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Post Hoc Description of Peak Features. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010104

Chicago/Turabian StyleNichani, Kapil, Steffen Uhlig, Victor San Martin, Karina Hettwer, Kirstin Frost, Ulrike Steinacker, Heike Kaspar, Petra Gowik, and Sabine Kemmlein. 2026. "Non-Targeted Screening Method for Detecting Temporal Shifts in Spectral Patterns of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Post Hoc Description of Peak Features" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010104

APA StyleNichani, K., Uhlig, S., San Martin, V., Hettwer, K., Frost, K., Steinacker, U., Kaspar, H., Gowik, P., & Kemmlein, S. (2026). Non-Targeted Screening Method for Detecting Temporal Shifts in Spectral Patterns of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Post Hoc Description of Peak Features. Microorganisms, 14(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010104