Benthic Microbial Community Features and Environmental Correlates in the Northwest Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Field, with Comparative Analysis Across the Pacific

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

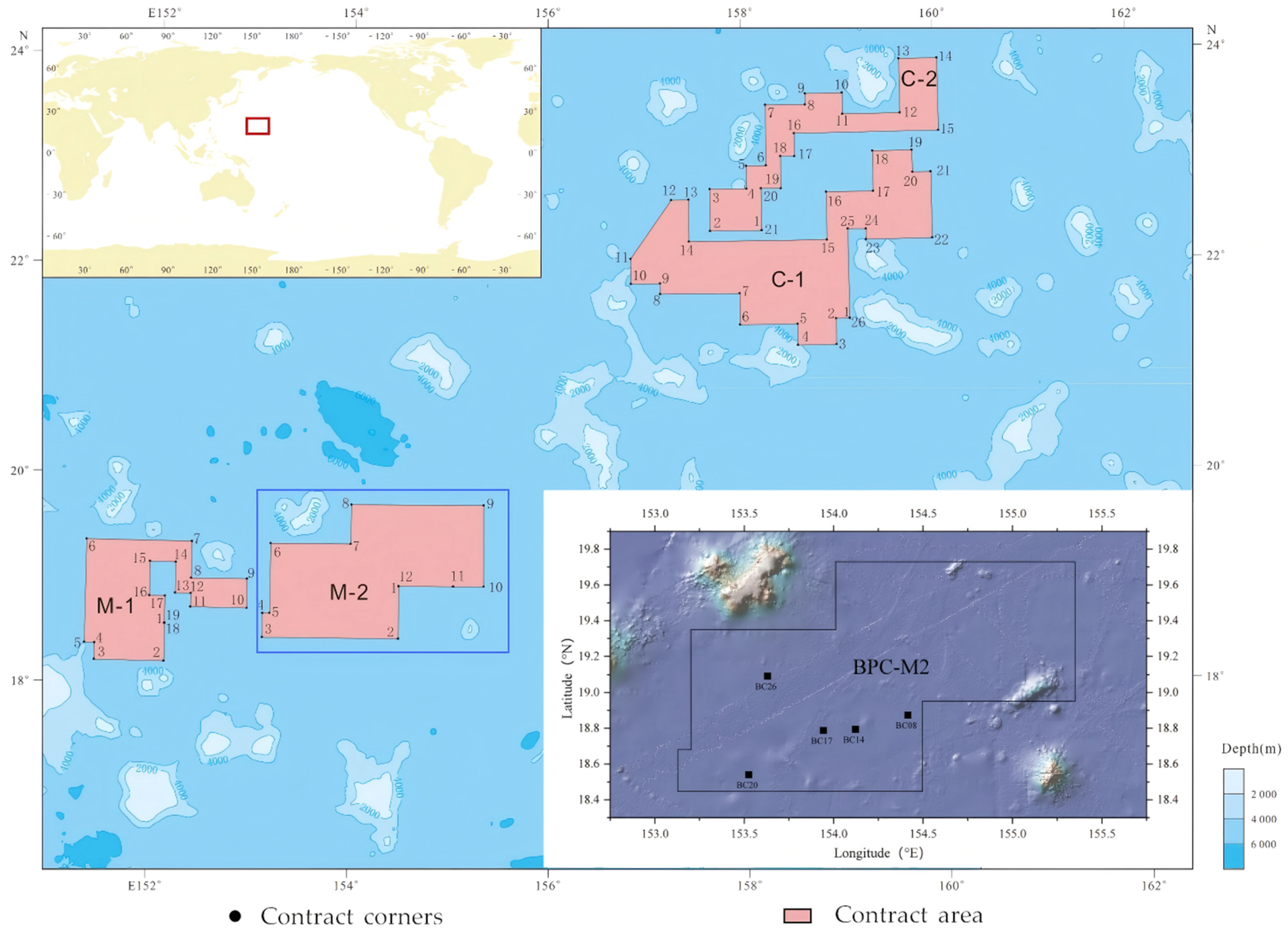

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. DNA Extraction and Amplicon Sequencing Analysis

2.3. Sequencing Data Processing and Downstream Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.5. Measurement of TOC, TN, and Stable Isotope Composition in Sediment Samples

3. Results

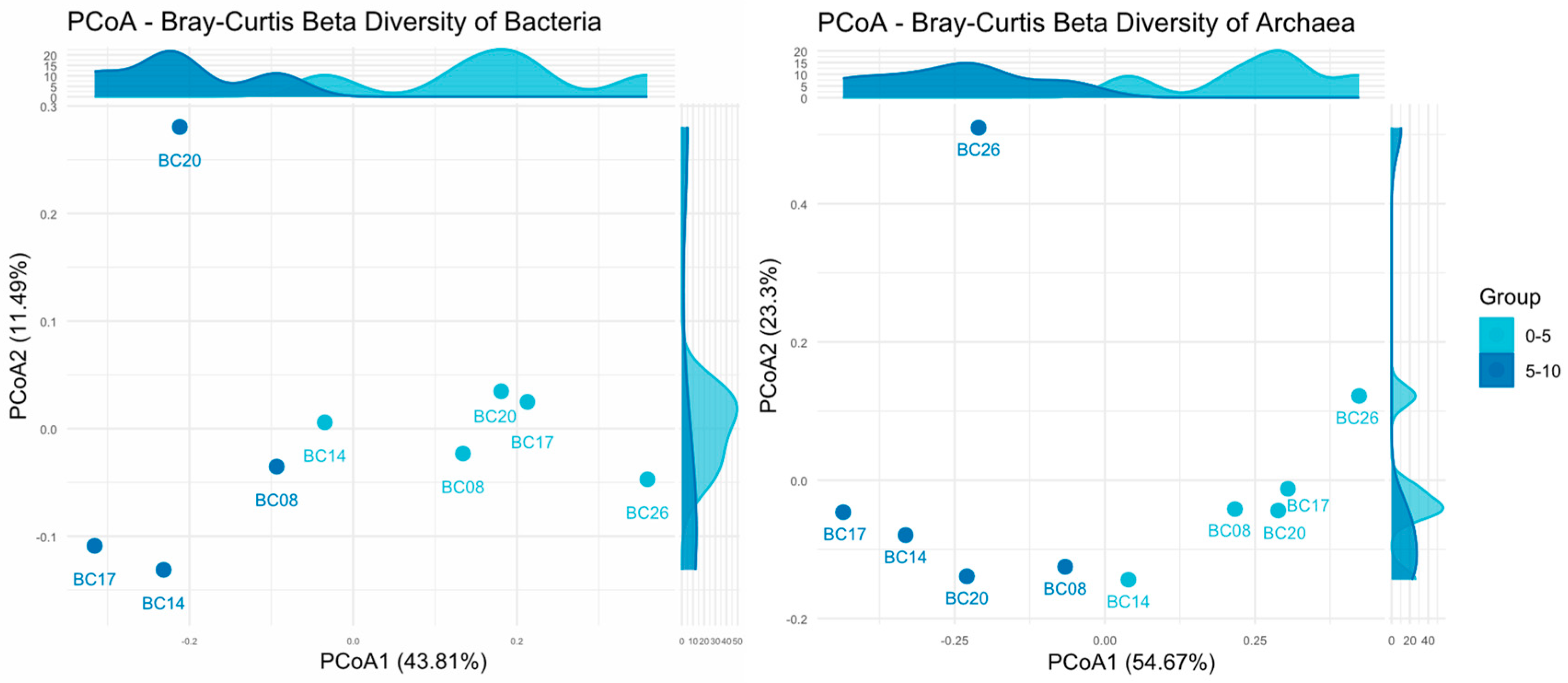

3.1. Microbial Community Structure and Distribution Patterns in the Western Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Field

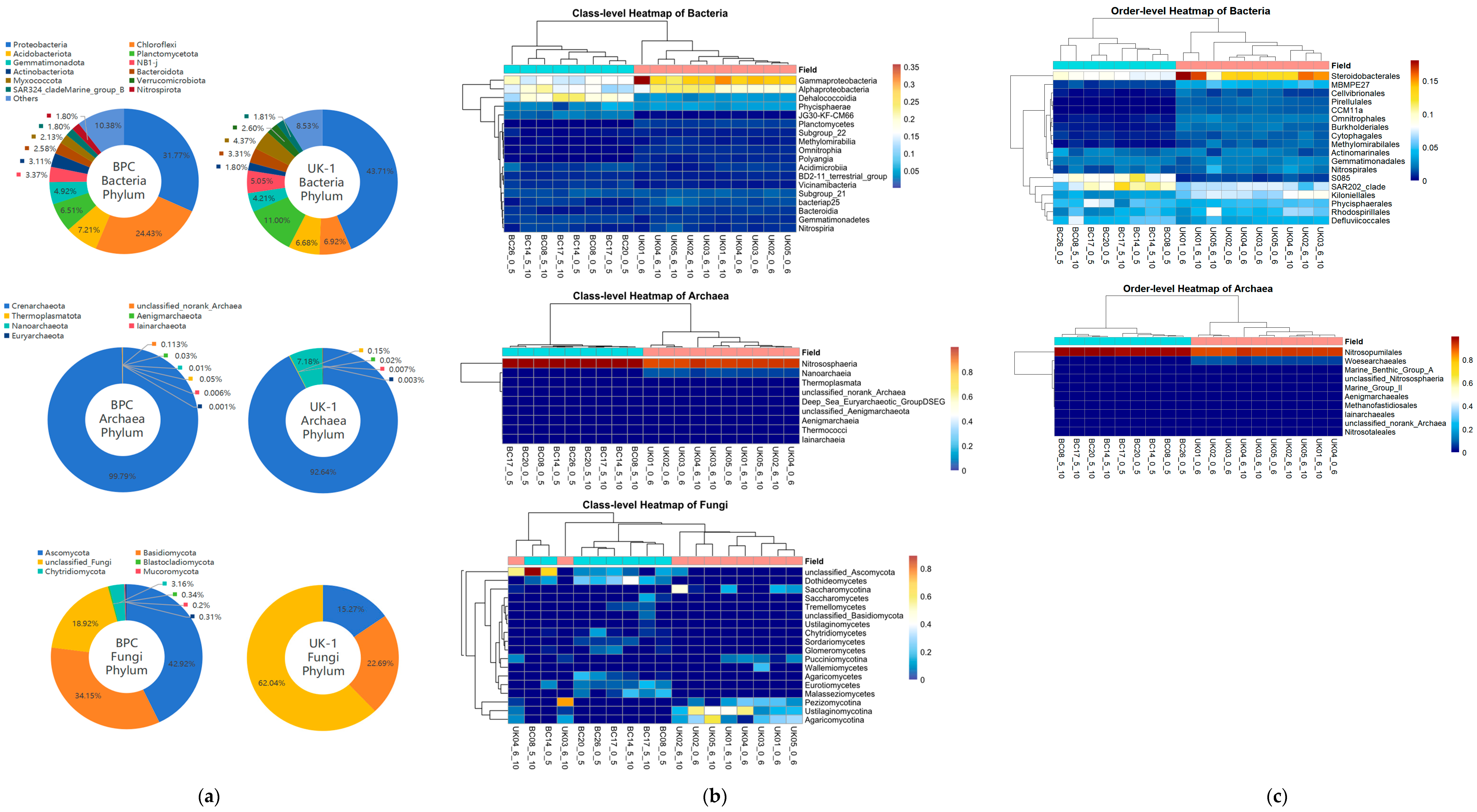

3.1.1. Microbial Community Composition

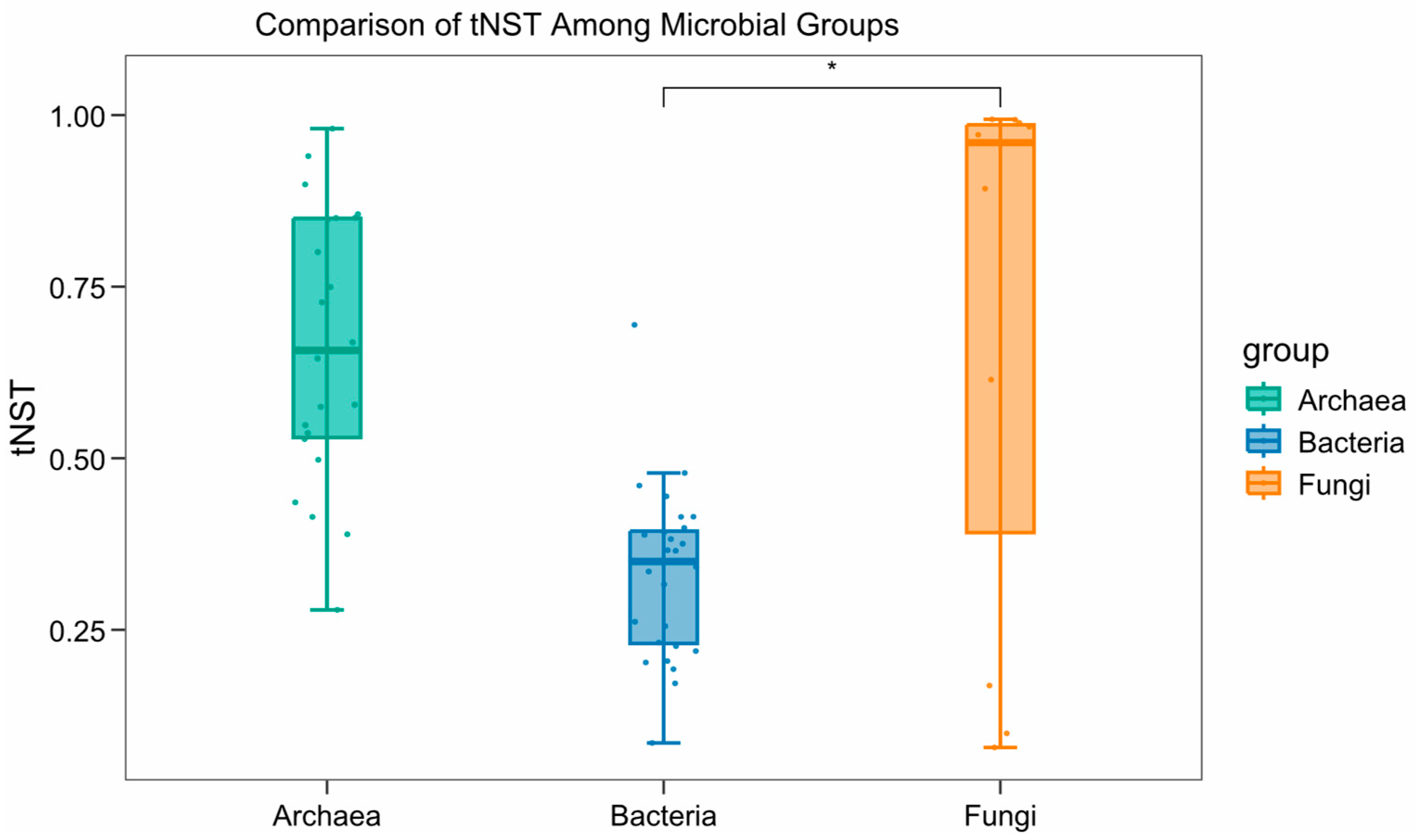

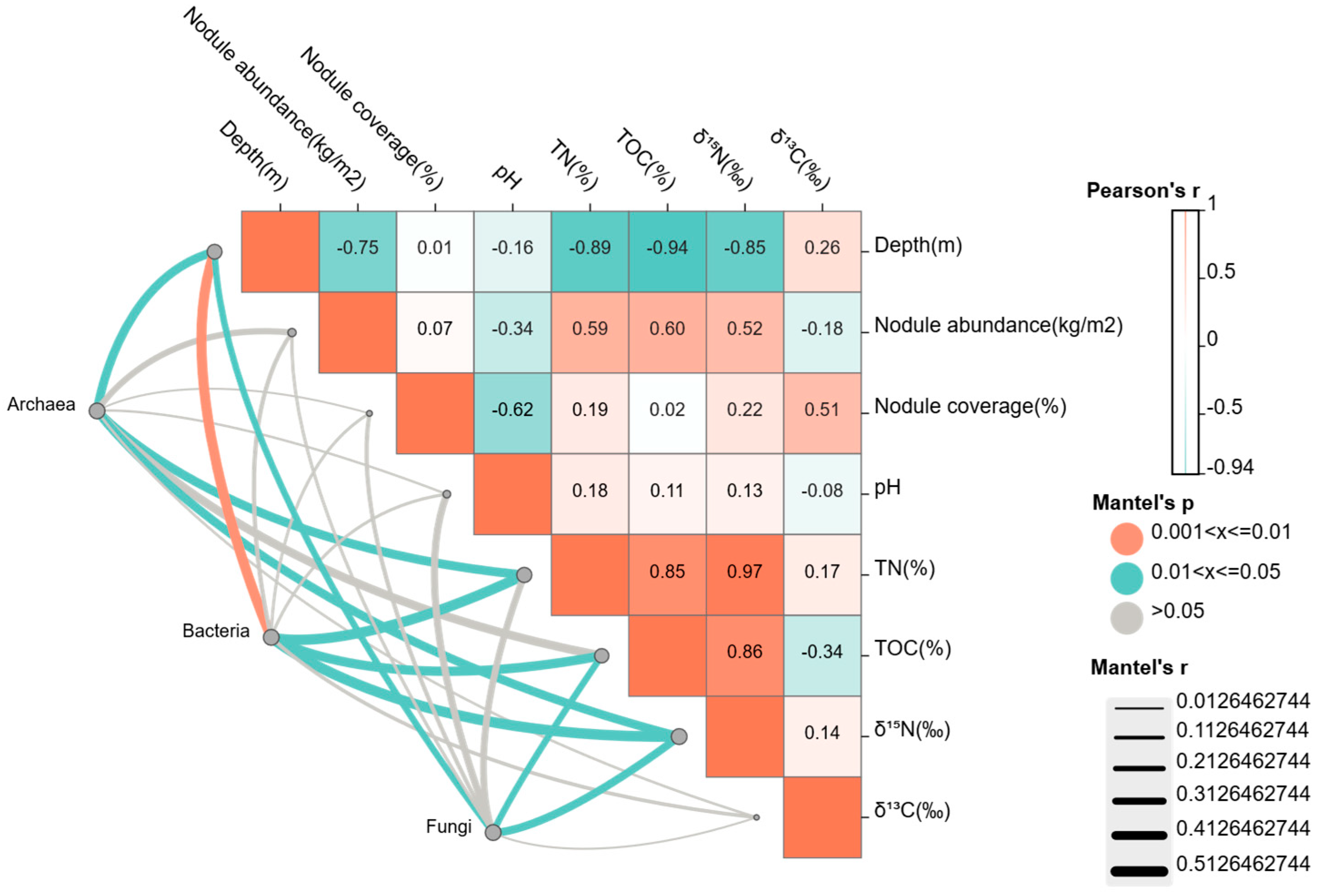

3.1.2. Correlations Between Microbial Communities and Environmental Factors

3.2. Microbial Community Differences Between the Eastern and Western Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Fields

3.2.1. Compositional Differences of Microbial Communities in the Eastern and Western Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Fields

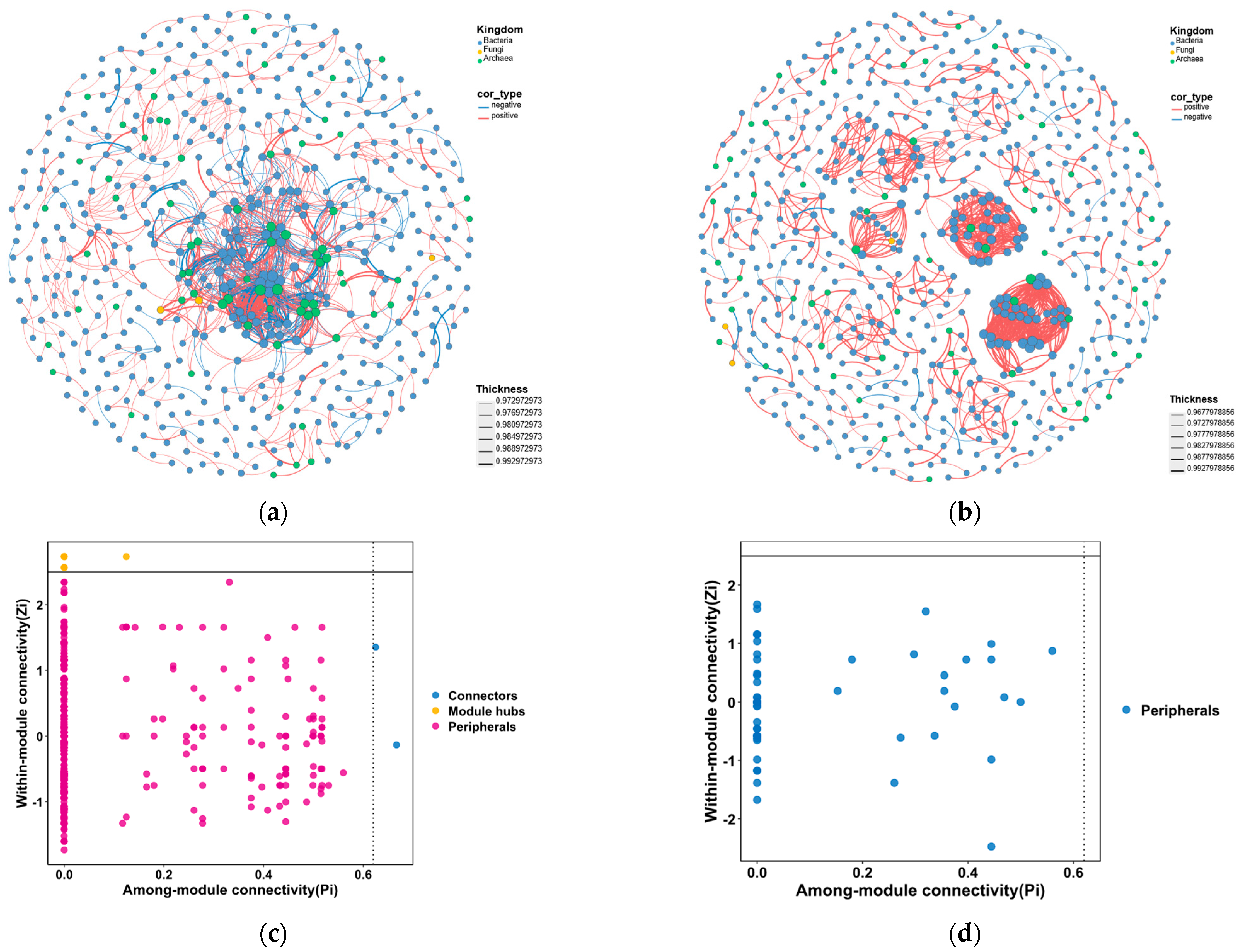

3.2.2. Differences in Microbial Co-Occurrence Networks

4. Discussion

4.1. Response of Microbial Community Structure to Environment in the Western Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Field

4.2. Factors Contributing to the Differences in Microbial Community Structure Between the Eastern and Western Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Fields

4.3. Potential Stability of Microbial Community Structure in the Eastern and Western Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Fields

5. Conclusions

- The BPC exhibited relatively high biodiversity. Bacterial communities were dominated by Proteobacteria and Chloroflexi, while Crenarchaeota represented the absolute dominant archaeal group. Fungal communities showed considerable variability, with Ascomycotina and Basidiomycota being the predominant phyla at most sites.

- Microbial groups displayed differential correlations with different environmental factors. Community composition was particularly strongly associated with water depth, TOC, TN, and δ15N.

- The microbial communities in the eastern and western Pacific nodule fields exhibited certain similarities but also some differences at the phylum, class, and order levels, with the differences becoming increasingly pronounced at finer taxonomic resolutions. These differences were evident in: Chloroflexi were more prominent in the BPC, whereas Proteobacteria and Planctomycetota showed higher relative abundances in the UK-1, with differences becoming increasingly pronounced at the class and order levels within these phyla. Among archaea, Nanoarchaeota (Nanoarchaeia–Woesearchaeales) were more abundant in the UK-1 than in the BPC. For fungi, Ascomycota and Basidiomycota accounted for a larger proportion of the community in the BPC compared with the UK-1 and showed pronounced compositional differences at the class level.

- Compared with UK-1, the BPC displayed distinct differences in co-occurrence patterns. The co-occurrence network in the BPC exhibited higher network density and node connectivity, whereas the UK-1 showed greater modularity and clustering coefficient, indicating that the microbial communities in the BPC had lower stability and resistance to disturbance relative to those in the UK-1 under future deep-sea mining disturbance.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hein, J.R.; Koschinsky, A.; Kuhn, T. Deep-Ocean Polymetallic Nodules as a Resource for Critical Materials. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; He, G.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. Oxic Bottom Water Dominates Polymetallic Nodule Formation around the Caiwei Guyot, Northwestern Pacific Ocean. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 143, 104776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, C.R.; Schlacher, T.A. On Some Hypotheses of Diversity of Animal Life at Great Depths on the Sea Floor. Mar. Ecol. 2015, 36, 849–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljutin, D.M.; Miljutina, M.A.; Arbizu, P.M.; Galeron, J. Deep-Sea Nematode Assemblage Has Not Recovered 26 Years after Experimental Mining of Polymetallic Nodules (Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, Tropical Eastern Pacific). Deep. Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2011, 58, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J.R.; Spinardi, F.; Okamoto, N.; Mizell, K.; Thorburn, D.; Tawake, A. Critical Metals in Manganese Nodules from the Cook Islands EEZ, Abundances and Distributions. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 68, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, C.; Kuhn, T.; Versteegh, G.J.; Wegorzewski, A.V.; Kasten, S. The Geochemical Behavior of Metals during Early Diagenetic Alteration of Buried Manganese Nodules. Deep. Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2018, 142, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, U.; Lüttke, T.; Raabe, D.; Souza Filho, I.R. Low-Waste, Single-Step, Sustainable Extraction of Critical Metals from Deep-Sea Polymetallic Nodules. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eaea1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, R.; Mori, Y.; Sakami, T. Comparison of Sulphate-Reducing Bacterial Communities in Japanese Fish Farm Sediments with Different Levels of Organic Enrichment. Microbes Environ. 2012, 27, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-L.; Rowe, G.T.; Escobar-Briones, E.; Boetius, A.; Soltwedel, T.; Caley, M.J.; Soliman, Y.; Huettmann, F.; Qu, F.; Yu, Z.; et al. Global Patterns and Predictions of Seafloor Biomass Using Random Forests. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wear, E.K.; Church, M.J.; Orcutt, B.N.; Shulse, C.N.; Lindh, M.V.; Smith, C.R. Bacterial and Archaeal Communities in Polymetallic Nodules, Sediments, and Bottom Waters of the Abyssal Clarion-Clipperton Zone: Emerging Patterns and Future Monitoring Considerations. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 634803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Liao, L.; Wang, C.-S.; Ma, W.-L.; Meng, F.-X.; Wu, M.; Xu, X.-W. A Comparison of Microbial Communities in Deep-Sea Polymetallic Nodules and the Surrounding Sediments in the Pacific Ocean. Deep. Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2013, 79, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöthe, M.; Wegorzewski, A.; Müller, C.; Simon, F.; Kuhn, T.; Schippers, A. Manganese-Cycling Microbial Communities Inside Deep-Sea Manganese Nodules. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 7692–7700, Erratum in Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 13080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.-S.; Liao, L.; Xu, H.-X.; Xu, X.-W.; Wu, M.; Zhu, L.-Z. Bacterial Diversity in the Sediment from Polymetallic Nodule Fields of the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone. J. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindh, M.V.; Maillot, B.M.; Shulse, C.N.; Gooday, A.J.; Amon, D.J.; Smith, C.R.; Church, M.J. From the Surface to the Deep-Sea: Bacterial Distributions across Polymetallic Nodule Fields in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Kim, K.-H.; Son, S.K.; Hyun, J.-H. Fine-Scale Microbial Communities Associated with Manganese Nodules in Deep-Sea Sediment of the Korea Deep Ocean Study Area in the Northeast Equatorial Pacific. Ocean. Sci. J. 2018, 53, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, K.; Takebe, H.; Murakami, C.; Tsune, A.; Okamura, T.; Ikegami, T.; Onishi, Y.; Kamikawa, R.; Yoshida, T. Population-Level Prokaryotic Community Structures Associated with Ferromanganese Nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (Pacific Ocean) Revealed by 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 16, e13224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, H.; Li, J.; Sun, D.; Wang, C.; Yang, J. The Structure of Bacterial Communities and Its Response to the Sedimentary Disturbance in the Surface Sediment of Western Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Area. J. Mar. Sci. 2021, 39, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aller, J.Y.; Kemp, P.F. Are Archaea Inherently Less Diverse than Bacteria in the Same Environments? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 65, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Shulse, C.N.; Maillot, B.; Smith, C.R.; Church, M.J. Polymetallic Nodules, Sediments, and Deep Waters in the Equatorial North Pacific Exhibit Highly Diverse and Distinct Bacterial, Archaeal, and Microeukaryotic Communities. Microbiol. Open 2017, 6, e00428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagrale, D.T.; Gawande, S.P. Archaea: Ecology, Application, and Conservation. In Microbial Resource Conservation: Conventional to Modern Approaches; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 431–451. [Google Scholar]

- Offre, P.; Spang, A.; Schleper, C. Archaea in Biogeochemical Cycles. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 67, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Salazar, A.; Muñoz-Velasco, I. Evolutionary Routes to Modern Metabolic Pathways. Macromol 2025, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, K.-U.; Hayes, J.M.; Sylva, S.P.; Brewer, P.G.; DeLong, E.F. Methane-Consuming Archaebacteria in Marine Sediments. Nature 1999, 398, 802–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms and Implications of Bacterial–Fungal Competition for Soil Resources. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Lu, T.; Li, J.; Zheng, Y.; Kong, L. Morphological and Genetic Characterization of a Cultivated Cordyceps Sinensis Fungus and Its Polysaccharide Component Possessing Antioxidant Property in H22 Tumor-Bearing Mice. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 2742–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Xu, W.; Gao, Y.; Chen, X.; Luo, Z.-H. Fungal Diversity in Deep-Sea Sediments from Magellan Seamounts Environment of the Western Pacific Revealed by High-Throughput Illumina Sequencing. J. Microbiol. 2020, 58, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orcutt, B.N.; Sylvan, J.B.; Knab, N.J.; Edwards, K.J. Microbial Ecology of the Dark Ocean above, at, and below the Seafloor. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 361–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Gao, D.; Wang, Y.; He, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, X. Distribution of Sediment Microbial Communities and Their Relationship with Surrounding Environmental Factors in a Typical Rural River, Southwest China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 84206–84225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.O.; Simon-Lledo, E.; Amon, D.J.; Bett, B.J.; Caulle, C.; Clement, L.; Connelly, D.P.; Dahlgren, T.G.; Durden, J.M.; Drazen, J.C.; et al. Environment, Ecology, and Potential Effectiveness of an Area Protected from Deep-Sea Mining (Clarion Clipperton Zone, Abyssal Pacific). Prog. Oceanogr. 2021, 197, 102653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, J.B.; Mogollón, J.M.; Geibert, W.; Arbizu, P.M.; Koschinsky, A.; Kasten, S. Natural Spatial Variability of Depositional Conditions, Biogeochemical Processes and Element Fluxes in Sediments of the Eastern Clarion-Clipperton Zone, Pacific Ocean. Deep. Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2018, 140, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rühlemann, C.; Kuhn, T.; Wiedicke, M.; Kasten, S.; Mewes, K.; Picard, A. Current Status of Manganese Nodule Exploration in the German License Area. In Proceedings of the ISOPE Ocean Mining and Gas Hydrates Symposium, Maui, HI, USA, 19–24 June 2011; ISOPE: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2011; p. ISOPE-M. [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin, D.; Semenov, M.; Chernov, T.; Ksenofontova, N.; Zhelezova, A.; Ivanova, E.; Khitrov, N.; Stepanov, A. Microbiological Indicators of Soil Ecological Functions: A Review. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2022, 55, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, E.C.; Morin, M.; Little, J.C.; Liu, R.B.; Tannous, J.; Keller, N.P.; Pogliano, K.; Wolfe, B.E.; Sanchez, L.M.; Dutton, R.J. Bacterial–Fungal Interactions Revealed by Genome-Wide Analysis of Bacterial Mutant Fitness. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, B.; Maron, P.A.; Chemidlin-Prevost Boure, N.; Bernard, N.; Gilbert, D.; Ranjard, L. Microbial Diversity and Ecological Networks as Indicators of Environmental Quality. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2017, 15, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, S.; Gao, X.; He, X.; Dong, S. Core Microbes Regulate Plant-Soil Resilience by Maintaining Network Resilience during Long-Term Restoration of Alpine Grasslands. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Fei, X.; Sun, Y.; Shao, H.; Zhu, J.; He, X.; Wang, X.; Yong, B.; Tao, X. Abscisic Acid-Polyacrylamide (ABA-PAM) Treatment Enhances Forage Grass Growth and Soil Microbial Diversity under Drought Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 973665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.C.; Cleary, D.F.; Almeida, A.; Cunha, Â.; Dealtry, S.; Mendonça-Hagler, L.C.; Smalla, K.; Gomes, N.C. Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis and Barcoded Pyrosequencing Reveal Unprecedented Archaeal Diversity in Mangrove Sediment and Rhizosphere Samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5520–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Z.; Hou, L.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Yan, B. Elucidating the Archaeal Community and Functional Potential in Two Typical Coastal Wetlands with Different Stress Patterns. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; He, Z.; Wang, C.; Yan, Q.; Shu, L. Evaluation of Different Primers of the 18S rRNA Gene to Profile Amoeba Communities in Environmental Samples. Water Biol. Secur. 2022, 1, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, D.; Deng, Y.; Tiedje, J.M.; Zhou, J. A General Framework for Quantitatively Assessing Ecological Stochasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 16892–16898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böer, S.; Hedtkamp, S.; van Beusekom, J.; Fuhrman, J.; Boetius, A.; Ramette, A. Time-and Sediment Depth-Related Variations in Bacterial Diversity and Community Structure in Subtidal Sandy Sediments. Investigation of the Distribution and Activity of Benthic Microorganisms in Coastal Habitats. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany, November 2008; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Shurin, J.B.; Cottenie, K.; Hillebrand, H. Spatial Autocorrelation and Dispersal Limitation in Freshwater Organisms. Oecologia 2009, 159, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Cong, B.; Zhang, W.; Lu, T.; Guo, N.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S. Comparative Metagenomics Reveals Microbial Diversity and Biogeochemical Drivers in Deep-Sea Sediments of the Marcus-Wake and Magellan Seamounts. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wei, X.; Song, W.; Wang, L.; Cao, J.; Wu, J.; Thomas, T.; Jin, T.; Wang, Z.; Wei, W.; et al. Novel Chloroflexi Genomes from the Deepest Ocean Reveal Metabolic Strategies for the Adaptation to Deep-Sea Habitats. Microbiome 2022, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, M.; Kimes, N.E.; Haro-Moreno, J.M.; Rodriguez-Valera, F. Not All Particles Are Equal: The Selective Enrichment of Particle-Associated Bacteria from the Mediterranean Sea. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woebken, D.; Teeling, H.; Wecker, P.; Dumitriu, A.; Kostadinov, I.; DeLong, E.F.; Amann, R.; Glöckner, F.O. Fosmids of Novel Marine Planctomycetes from the Namibian and Oregon Coast Upwelling Systems and Their Cross-Comparison with Planctomycete Genomes. ISME J. 2007, 1, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, H.; Hohn, M.J.; Rachel, R.; Fuchs, T.; Wimmer, V.C.; Stetter, K.O. A New Phylum of Archaea Represented by a Nanosized Hyperthermophilic Symbiont. Nature 2002, 417, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Zhang, J.; Liu, R.; Sun, C. Metagenomic Insights into the Metabolic and Ecological Functions of Abundant Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent DPANN Archaea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e03009-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Velasco, I.; García-Ferris, C.; Hernandez-Morales, R.; Lazcano, A.; Peretó, J.; Becerra, A. Methanogenesis on Early Stages of Life: Ancient but Not Primordial. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2018, 48, 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Cruz, S.; Vaksmaa, A.; Horn, M.A.; Niemann, H.; Pijuan, M.; Ho, A. Methanotrophs: Discoveries, Environmental Relevance, and a Perspective on Current and Future Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 678057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Zhao, Z.; Breyer, E.; Baltar, F. Organic Matter Degradation by Oceanic Fungi Differs between Polar and Non-Polar Waters. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Pan, J.; Cron, B.R.; Toner, B.M.; Anantharaman, K.; Breier, J.A.; Dick, G.J.; Li, M. Gammaproteobacteria Mediating Utilization of Methyl-, Sulfur-and Petroleum Organic Compounds in Deep Ocean Hydrothermal Plumes. ISME J. 2020, 14, 3136–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasmund, K.; Schreiber, L.; Lloyd, K.G.; Petersen, D.G.; Schramm, A.; Stepanauskas, R.; Jørgensen, B.B.; Adrian, L. Genome Sequencing of a Single Cell of the Widely Distributed Marine Subsurface Dehalococcoidia, Phylum Chloroflexi. ISME J. 2014, 8, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, S.; Sun, X.; Liang, J.; Tian, Z.; Liu, T. Biomass of Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton and Primary Producivity at M2 Seamount in Tropical West Pacific in Spring 2016. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2017, 48, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar]

- An, L.; Huang, Y.; Xu, C.; Xu, F.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, B. Biogeochemical Characteristics and Phytoplankton Community Diversity of the Western North Equatorial Current. Glob. Planet. Change 2025, 252, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Song, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhong, G.; Yuan, H.; Li, N.; Duan, L. The OMZ and Its Influence on POC in the Tropical Western Pacific Ocean: Based on the Survey in March 2018. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 632229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mooy, B.A.; Keil, R.G.; Devol, A.H. Impact of Suboxia on Sinking Particulate Organic Carbon: Enhanced Carbon Flux and Preferential Degradation of Amino Acids via Denitrification. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2002, 66, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulmier, A.; Ruiz-Pino, D. Oxygen Minimum Zones (OMZs) in the Modern Ocean. Prog. Oceanogr. 2009, 80, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Li, J.; Li, H. Bacterial Contributions to the Formation of Polymetallic Nodules in the Pacific Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1533654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlaan, P.A.; Cronan, D.S.; Morgan, C.L. A Comparative Analysis of Compositional Variations in and between Marine Ferromanganese Nodules and Crusts in the South Pacific and Their Environmental Controls. Prog. Oceanogr. 2004, 63, 125–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J.R.; Koschinsky, A. Deep-Ocean Ferromanganese Crusts and Nodules. Treatise Geochem. 2014, 13, 273–291. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.C.; Owen, R.M. The Hydrothermal Component in Ferromanganese Nodules from the Southeast Pacific Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1989, 53, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, F.T.; Griffiths, R.I.; Bailey, M.; Craig, H.; Girlanda, M.; Gweon, H.S.; Hallin, S.; Kaisermann, A.; Keith, A.M.; Kretzschmar, M.; et al. Soil Bacterial Networks Are Less Stable under Drought than Fungal Networks. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, P.; Ledwell, J.; Thurnherr, A. Dispersion of a Tracer on the East Pacific Rise (9 N to 10 N), Including the Influence of Hydrothermal Plumes. Deep. Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2010, 57, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, L.; Beirinckx, S.; Haegeman, A.; Debode, J.; Vandecasteele, B.; Baeyen, S.; Goormachtig, S.; Clement, L.; De Tender, C. Daring to Be Differential: Metabarcoding Analysis of Soil and Plant-Related Microbial Communities Using Amplicon Sequence Variants and Operational Taxonomical Units. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarello, M.; McCauley, M.; Villéger, S.; Jackson, C.R. Ranking the Biases: The Choice of OTUs vs. ASVs in 16S rRNA Amplicon Data Analysis Has Stronger Effects on Diversity Measures than Rarefaction and OTU Identity Threshold. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S.P. Exact Sequence Variants Should Replace Operational Taxonomic Units in Marker-Gene Data Analysis. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2639–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasolo, A.; Deb, S.; Stevanato, P.; Concheri, G.; Squartini, A. ASV vs. OTUs Clustering: Effects on Alpha, Beta, and Gamma Diversities in Microbiome Metabarcoding Studies. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, J.T.; Gallert, C. Microbiome Analysis via OTU and ASV-Based Pipelines—A Comparative Interpretation of Ecological Data in WWTP Systems. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Bai, L.; Yao, Z.; Li, W.; Yang, W. Seasonal Lake Ice Cover Drives the Restructuring of Bacteria-Archaea and Bacteria-Fungi Interdomain Ecological Networks across Diverse Habitats. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertness, M.D.; Callaway, R. Positive Interactions in Communities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1994, 9, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappelini, C.; Karimi, B.; Foulon, J.; Lacercat-Didier, L.; Maillard, F.; Valot, B.; Blaudez, D.; Cazaux, D.; Gilbert, D.; Yergeau, E.; et al. Diversity and Complexity of Microbial Communities from a Chlor-Alkali Tailings Dump. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 90, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitlhou, L.; Chakraborty, P. Comparing Deep-Sea Polymetallic Nodule Mining Technologies and Evaluating Their Probable Impacts on Deep-Sea Pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 206, 116762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koschinsky, A.; Fritsche, U.; Winkler, A. Sequential Leaching of Peru Basin Surface Sediment for the Assessment of Aged and Fresh Heavy Metal Associations and Mobility. Deep. Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2001, 48, 3683–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, I.; Haeckel, M.; Lougear, A.; Suess, E.; Trautwein, A.X. A Geochemical Model of the Peru Basin Deep-Sea Floor—And the Response of the System to Technical Impacts. Deep. Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2001, 48, 3737–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.A.; Gaye, B.; Haeckel, M.; Kasten, S.; Koschinsky, A. Biogeochemical Regeneration of a Nodule Mining Disturbance Site: Trace Metals, DOC and Amino Acids in Deep-Sea Sediments and Pore Waters. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinebrooke, D.R.; Cottingham, L.K.; Norberg, J.; Scheffer, M.; Dodson, I.S.; Maberly, C.S.; Sommer, U. Impacts of Multiple Stressors on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning: The Role of Species Co-Tolerance. Oikos 2004, 104, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Primer | Target Region | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) | 16S rRNA V3–V4 | [36] |

| / 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) | |||

| Fungi | 1380F (5′-CCCTGCCHTTTGTACACAC-3′) | 18S rRNA V9 | [37,38] |

| / 1510R (5′-CCTTCYGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3′) | |||

| Archaea | 524F10extF (5′-TGYCAGCCGCCGCGGTAA-3′) | 16S rRNA V5–V6 | [39] |

| / Arch958RmodR (5′-YCCGGCGTTGAVTCCAAT-3′) |

| Sample_Info | Bacteria_ASV | Bacteria_Seq | Archaea_ASV | Archaea_Seq | Eukaryota_ASV | Eukaryota_Seq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC08_0_5 | 2444 | 52776 | 197 | 24465 | 794 | 74291 |

| BC08_5_10 | 1758 | 51828 | 142 | 25328 | 338 | 71976 |

| BC14_0_5 | 1842 | 51828 | 170 | 25998 | 385 | 69240 |

| BC14_5_10 | 1697 | 50696 | 117 | 22702 | 210 | 68070 |

| BC17_0_5 | 2803 | 49063 | 191 | 18910 | 1419 | 81448 |

| BC17_5_10 | 1205 | 51149 | 74 | 24208 | 261 | 43214 |

| BC20_0_5 | 2433 | 47741 | 178 | 20886 | 1081 | 51451 |

| BC20_5_10 | 1238 | 31566 | 85 | 23193 | - | - |

| BC26_0_5 | 2623 | 52947 | 179 | 23664 | 1156 | 67722 |

| BC26_5_10 | - | - | 38 | 53530 | 191 | 385918 |

| Edges Number | Positive Edges | Negative Edges | Nodes Number | Average Degree | Average Clustering Coefficient | Modularity | Network Diameter | Average Path Length | Density | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPC | 1268 | 66% | 34% | 541 | 4.688 | 0.106 | 0.640 | 20.501 | 5.227 | 0.0087 |

| UK | 1008 | 96.5% | 3.5% | 632 | 3.180 | 0.277 | 0.876 | 7.839 | 1.691 | 0.0051 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Yang, J.; He, X.; Zhao, Z.; Xia, J. Benthic Microbial Community Features and Environmental Correlates in the Northwest Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Field, with Comparative Analysis Across the Pacific. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010103

Li Z, Yang J, He X, Zhao Z, Xia J. Benthic Microbial Community Features and Environmental Correlates in the Northwest Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Field, with Comparative Analysis Across the Pacific. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010103

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ziyu, Juan Yang, Xuebao He, Ziyu Zhao, and Jianxin Xia. 2026. "Benthic Microbial Community Features and Environmental Correlates in the Northwest Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Field, with Comparative Analysis Across the Pacific" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010103

APA StyleLi, Z., Yang, J., He, X., Zhao, Z., & Xia, J. (2026). Benthic Microbial Community Features and Environmental Correlates in the Northwest Pacific Polymetallic Nodule Field, with Comparative Analysis Across the Pacific. Microorganisms, 14(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010103