Transcriptomic Profiling of mRNA and lncRNA During the Developmental Transition from Spores to Mycelia in Penicillium digitatum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pathogen and Morphological Observation

2.2. Detection of Fungal Physiological Characteristics

2.3. Sample Preparation and qRT-PCR Validation

2.4. Transcriptomic Analysis

2.5. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Characteristics of P. digitatum Across Developmental Stages

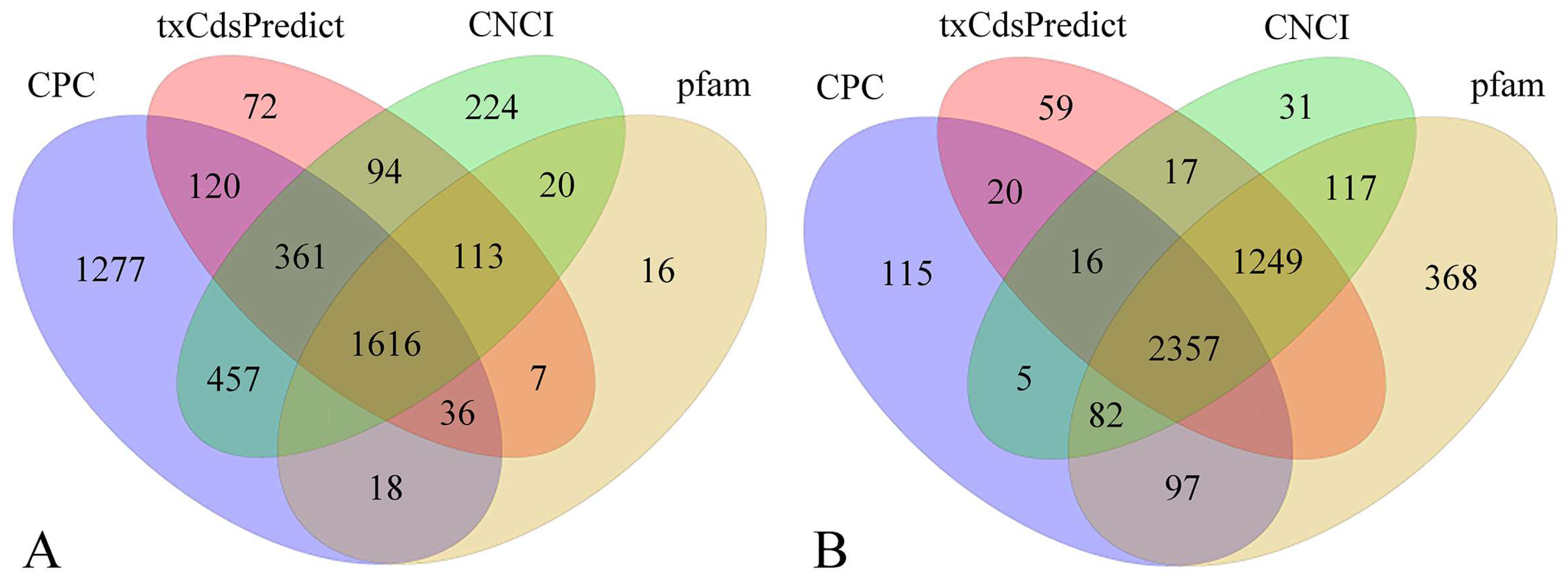

3.2. Transcriptome Assembly Annotation

3.3. SNP and InDel Analysis

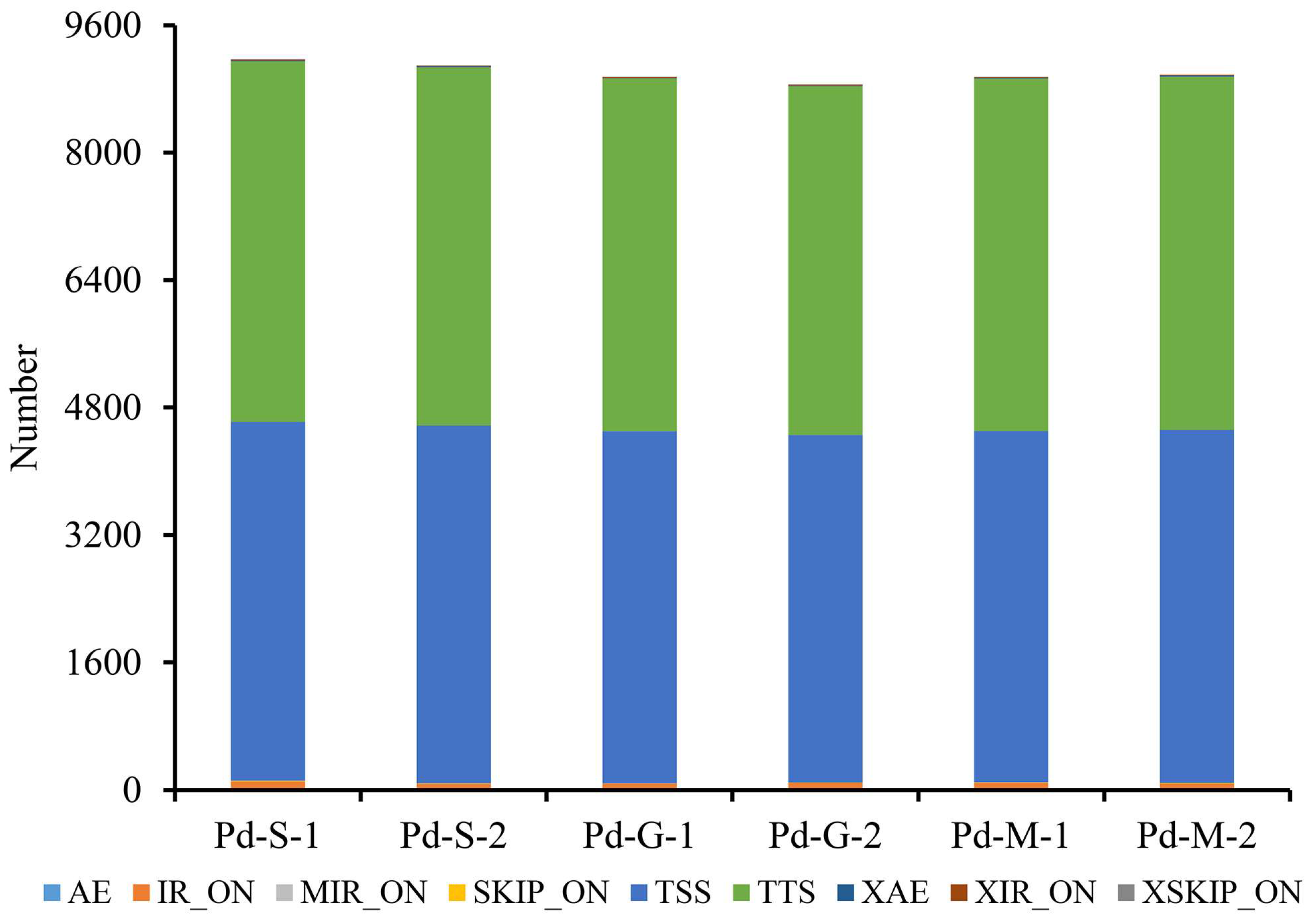

3.4. AS and DSG Analysis

3.5. Differential Expression Analysis and RT-qPCR Validation

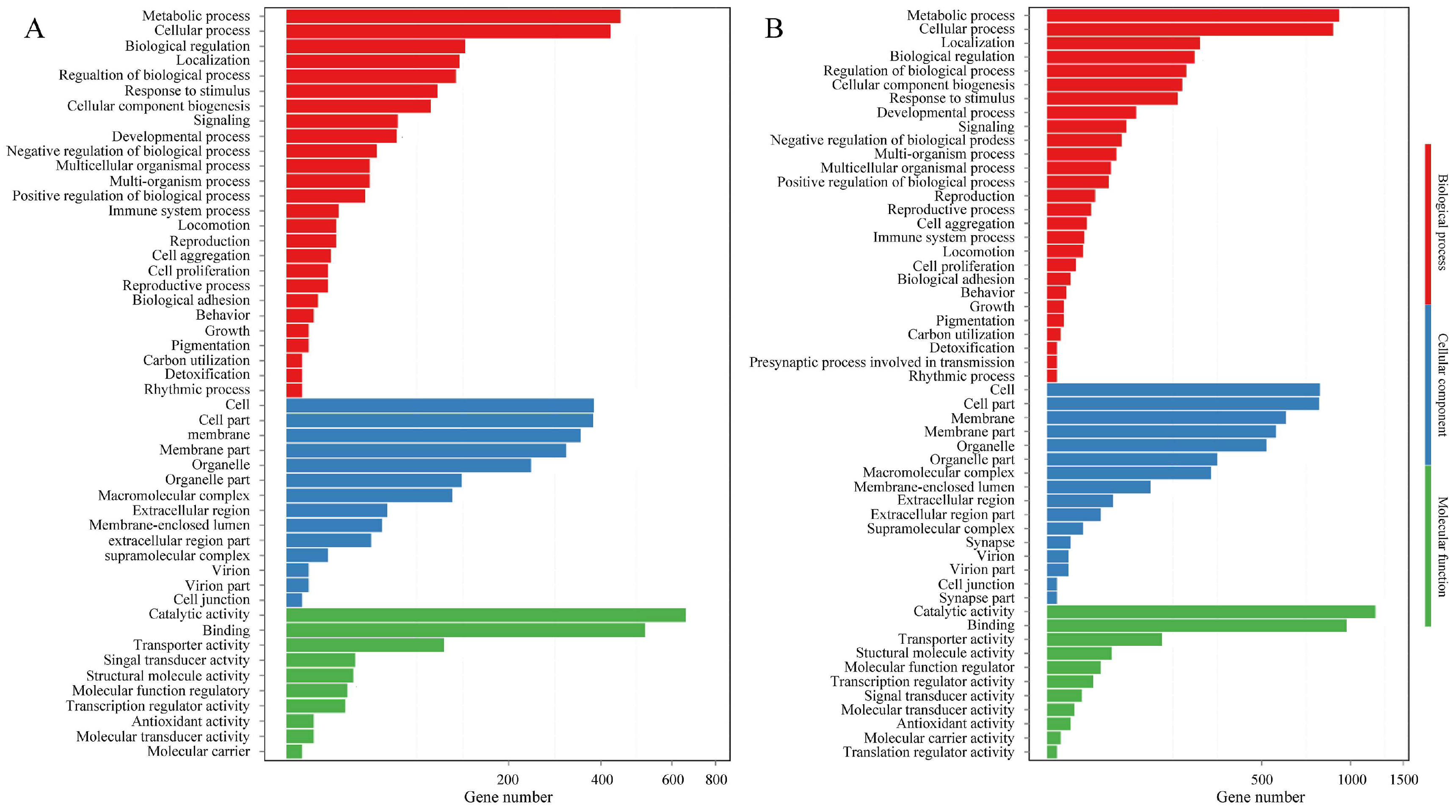

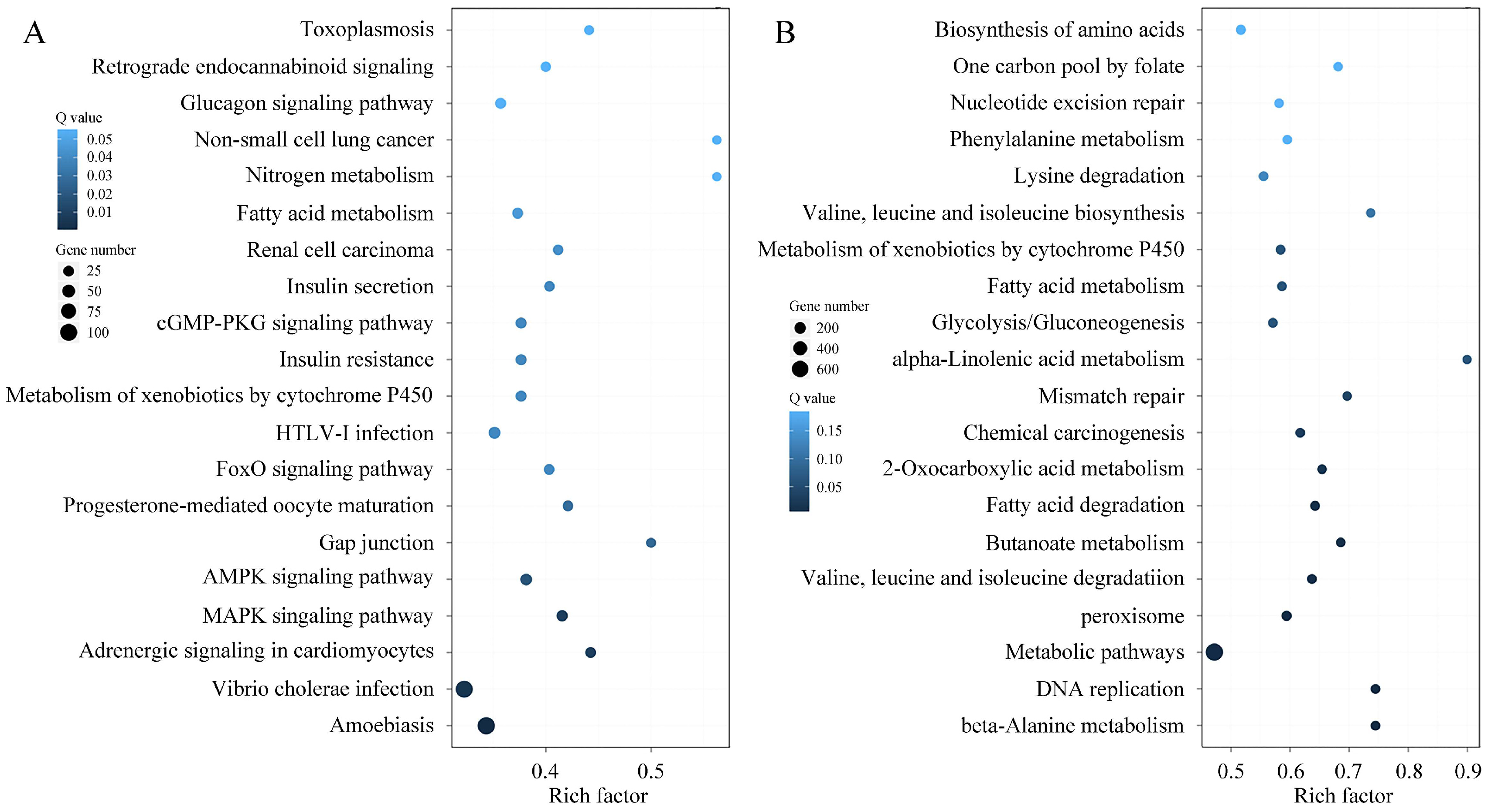

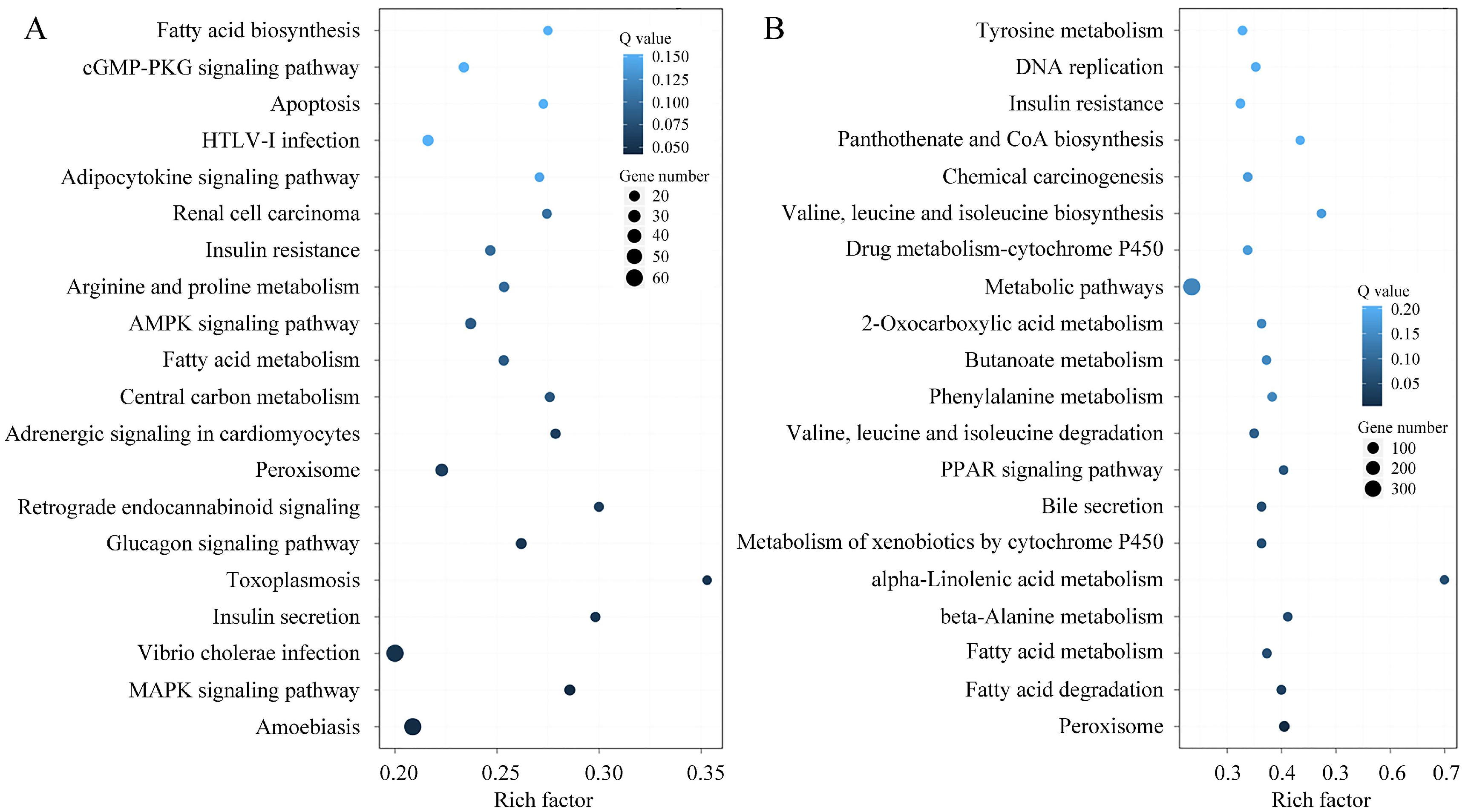

3.6. Functional Enrichment Analysis

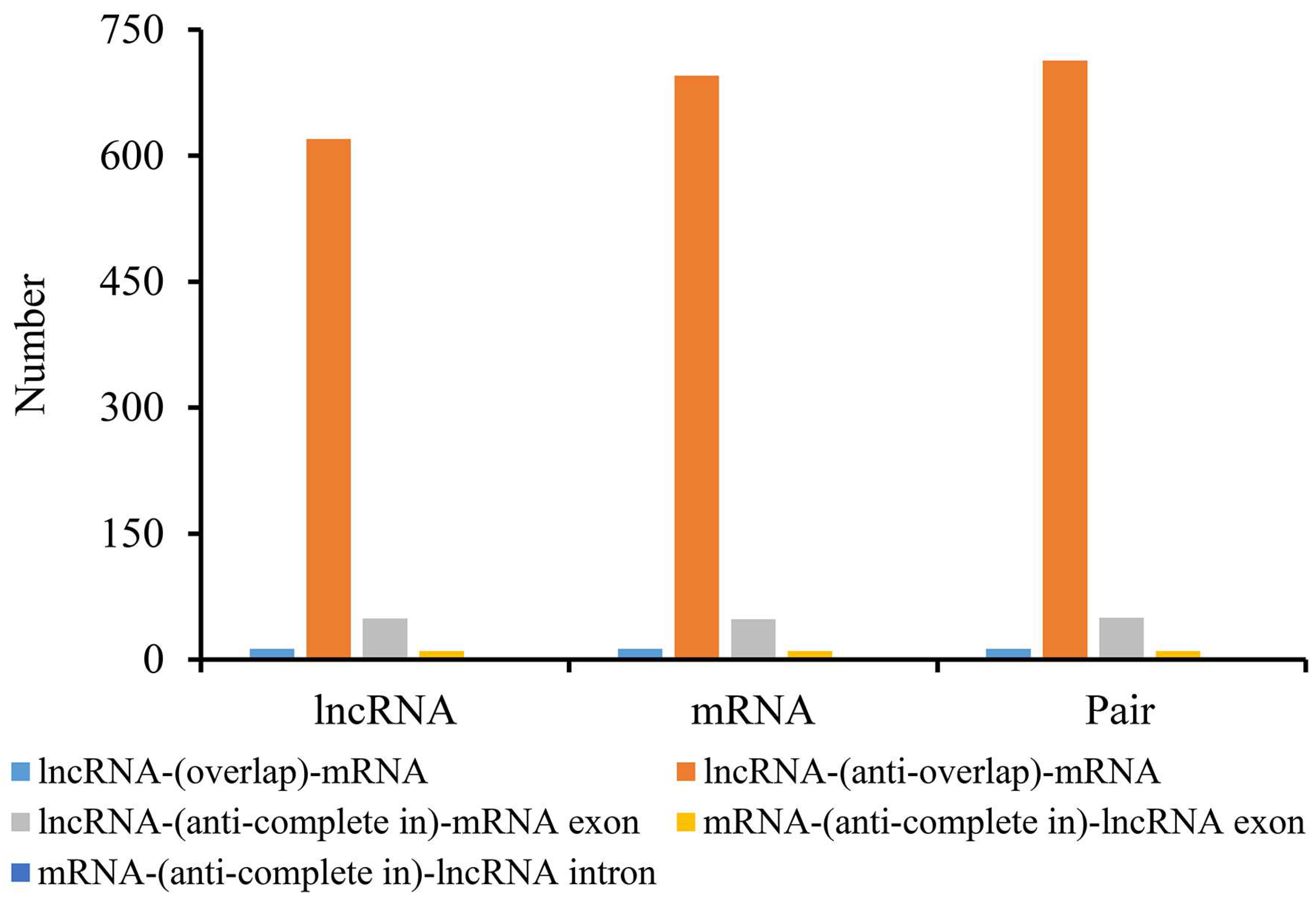

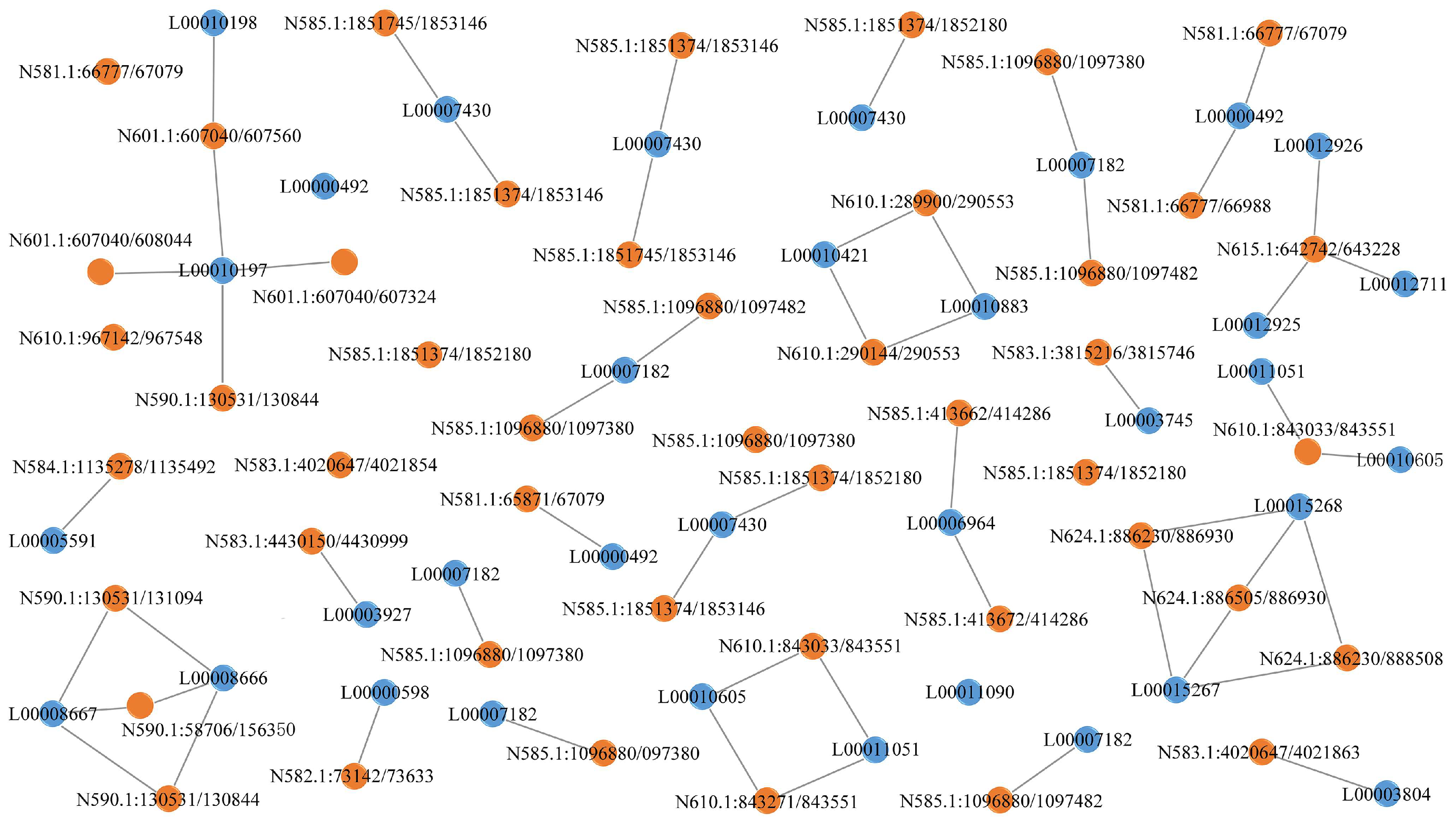

3.7. Interaction Analysis of lncRNAs-mRNAs and lncRNAs-circRNAs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| P. digitatum | Penicillium digitatum |

| Pd-S | Spores of P. digitatum |

| Pd-G | Germinated spores of P. digitatum |

| Pd-M | Mycelia of P. digitatum |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time PCR |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| SNPs | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| INDEL | Insertion-Deletion |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

References

- Marcet-Houben, M.; Ballester, A.B.; Fuente, B.D.L.; Harries, E.; Marcos, J.; González-Candelas, L.; Gabaldón, T. Genome sequence of the necrotrophic fungus Penicillium digitatum, the main postharvest pathogen of citrus. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.H.; Bazioli, J.M.; Barbosa, L.D.; Júnior, P.L.T.D.S.; Reis, F.C.G.; Klimeck, T.; Crnkovic, C.M.; Berlinck, R.G.S.; Sussulini, A.; Rodrigues, M.L.; et al. Phytotoxic tryptoquialanines produced in vivo by Penicillum digitatum are exported in extracellular vesicles. mBio 2021, 12, e03393-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghooshkhaneh, N.G.; Golzarian, M.R.; Mamarabadi, M. Detection and classification of citrus green mold caused by Penicillium digitatum using multispectral imaging. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 3542–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, U.K. Alternative management approaches of citrus diseases caused by Penicillium digitatum (green mold) and Penicillium italicum (Blue mold). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 833328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palou, L.; Smilanick, J.L.; Droby, S. Alternatives to conventional fungicides for the control of citrus postharvest green and blue moulds. Stewart Postharvest Rev. 2008, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gandía, M.; Harries, E.; Marcos, J.F. Identification and characterization of chitin synthase genes in the postharvest citrus fruit pathogen Penicillium digitatum. Fungal Biol. 2012, 116, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandía, M.; Harries, J.; Marcos, J.F. The myosin motor domain-containing chitin synthase PdChSVII is required for development, cell wall integrity and virulence in the citrus postharvest pathogen Penicillium digitatum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014, 67, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harries, E.; GandÍa, M.; Carmona, L.; Marcos, J.F. The Penicillium digitatum protein O-mannosyltransferase Pmt2 is required for cell wall integrity, conidiogenesis, virulence and sensitivity to the antifungal peptide PAF26. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2015, 16, 748–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.Y.; Wang, M.S.; Wang, W.L.; Ruan, R.X.; Ma, H.J.; Mao, C.G.; Li, H.Y. Glucosylceramides are required for mycelial growth and full virulence in Penicillium digitatum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 455, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.Y.; Wang, W.L.; Wang, M.S.; Ruan, R.X.; Sun, X.P.; He, M.X.; Mao, C.G.; Li, H.Y. Deletion of PdMit1, a homolog of yeast Csg1, affects growth and Ca2+ sensitivity of fungus Penicillium digitatum, but does not alter virulence. Res. Microbiol. 2015, 166, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.J.; Zhu, J.F.; Tian, Z.H.; Long, C.A. PdStuA is a key transcription factor controlling sporulation, hydrophobicity, and stress tolerance in Penicillium digitatum. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Lu, Y.Q.; Du, Y.L.; Liu, S.Q.; Zhong, X.Y.; Du, Y.J.; Tian, Z.H. GAR-transferase contributes to purine synthesis and mitochondrion function to maintain fungal development and full virulence of Penicillium digitatum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 394, 110177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Liu, X.Y.; Lai, W.Q.; Lu, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.Q.; Long, C.A. PdMesA regulates polar growth, cell wall integrity, and full virulence in Penicillium digitatum of citrus. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 215, 113017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Yan, D.; Liu, J.J.; Yang, S.Z.; Li, D.M.; Peng, L.T. Vacuolar ATPase subunit H regulates growth development and pathogenicity of Penicillium digitatum. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 199, 112295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, L.; López-Pérez, M.; Ballester, A.R.; Teixidó, N.; Usall, J.; Lara, I.; Viñas, I.; Torres, R.; González-Candelas, L. Differential contribution of the two major polygalacturonases from Penicillium digitatum to virulence towards citrus fruit. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 282, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Yang, Q.Y.; Zhang, Q.D.; Abdelhai, M.H.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Serwah, B.N.A.S.; Gu, N.; Zhang, H.Y. Elucidation of the initial growth process and the infection mechanism of Penicillium digitatum on postharvest citrus (Citrus reticulate Blanco). Microorganisms 2019, 7, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.T.; Meng, K.X.; Shen, X.M.; Li, L.; Chen, X.M.; Tan, X.L.; Tao, N.G. Xyloglucan-specific endo-β-1, 4-glucanase (PdXEG1) gene is important for the growth, development and virulence of Penicillium digitatum. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 208, 112673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.U.; Sun, X.P.; Xu, Q. The pH signaling transcription factor PacC is required for full virulence in Penicillium digitatum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 9087–9098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.J.; Sun, X.P.; Wang, M.S.; Gai, Y.P.; Chung, K.R.; Li, H.Y. The citrus postharvest pathogen Penicillium digitatum depends on the PdMpkB kinase for developmental and virulence functions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 236, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandía, M.; Garrigues, S.; Hernanz-Koers, M.; Manzanares, P.; Marcos, J.F. Differential roles, crosstalk and response to the Antifungal Protein AfpB in the three Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPK) pathways of the citrus postharvest pathogen Penicillium digitatum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2019, 124, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.L.; Wang, M.S.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhu, C.Y.; Chung, K.R.; Li, H.Y. Adenylyl cyclase is required for cAMP production, growth, conidial germination, and virulence in the citrus green mold pathogen. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 192, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.J.; Zhu, J.F.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Yang, F.; Tian, Z.H.; Long, C.A. PdGpaA controls the growth and virulence of Penicillium digitatum by regulating cell wall reorganization, energy metabolism, and CDWEs production. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 204, 112441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.Y.; Xu, Q.; Sun, X.P.; Li, H.Y. The calcineurin-responsive transcription factor Crz1 is required for conidation, full virulence and DMI resistance in Penicillium expansum. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 168, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ramón-Carbonell, M.D.; Sánchez-Torres, P. Penicillium digitatum MFS transporters can display different roles during pathogen-fruit interaction. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 337, 108918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.Y.; Zhao, J.Y.; Yeung, P.Y.; Zhang, Q.F.C.; Kwok, C.K. Revealing lncRNA structures and interactions by sequencing-based approaches. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2019, 44, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridres, M.C.; Daulagala, A.C.; Kourtidis, A. LNCcation: LncRNA localization and function. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202009045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misir, S.; Wu, N.; Yang, B.B. Specific expression and functions of circular RNAs. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.J.; Kim, Y.K. Molecular mechanisms of circular RNA translation. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1272–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinek, M.; Doudan, J.A. A three-dimensional view of the molecular machinery of RNA interference. Nature 2009, 457, 405–412. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, S.; Izaurralde, E. Towards a molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 421–433. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.S.; Ruan, R.X.; Li, H.Y. The completed genome sequence of the pathogenic ascomycete fungus Penicillium digitatum. Genomics 2021, 113, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Torres, P.; Conzález-Candelas, L.; Ballester, A.R. Discovery and transcriptional profiling of Penicillium digitatum genes that could promote fungal virulence during citrus fruit infection. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.F.; Bai, X.L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.Y.; Shi, N.N.; Zhou, T. Inhibitory effect of exogenous sodium bicarbonate on development and pathogenicity of postharvest disease Penicillium expansum. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 187, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, B.S.; Johnston, P.R.; Damm, U. The Colletotrichum gloeosporioides species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 115–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desper, R.; Gascuel, O. Theoretical foundation of the balanced minimum evolution method of phylogenetic inference and its relationship to weighted least-squares three fitting. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004, 21, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Z.Q.; Liu, X.Q.; Zhao, S.Q.; Wei, L.P.; Gao, G. CPC: Assess the protein-coding potential of transcripts using sequence features and support vector machine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Luo, H.T.; Bu, D.C.; Zhao, G.G.; Yu, K.T.; Zhang, C.H.; Liu, Y.N.; Chen, R.S.; Zhao, Y. Utilizing sequence intrinsic composition to classify protein-coding and long non-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Mistry, J.; Mitchell, A.; Potter, S.C.; Punta, M.; Qureshi, M.; Sangrador-Vegas, A.; et al. The Pfam protein families database: Towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.K.; Feng, Z.X.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.W.; Zhang, X.G. DEGseq: An R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Futschik, M. Mfuzz: A software are package for soft clustering of microarray data. Bioinformation 2007, 2, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Conesa, A.; Götz, S.; GarcÍa-Gómez, J.M.; Terol, J.; Talón, M.; Robles, M. Blast2GO: A universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3674–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevillon, E.; Silventoinen, V.; Pillai, S.; Harte, N.; Mulder, N.; Apweiler, R.; Lopez, R. InterProScan: Protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, L.; Song, L.; Salzberg, S.L. Thousands of exon skipping events differentiate among splicing patterns in sixteen human tissues. F1000Research 2013, 2, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.H.; Park, J.W.; Lu, Z.X.; Lin, L.; Henry, M.D.; Wu, Y.N.; Zhou, Q.; Xing, Y. rMATS: Robust and flexible detection of differential alternative splicing from replicate RNA-Seq data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5593–5601. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, J.F.; Zhao, F.Q. CIRI: An efficient and unbiased algorithm for de novo circular RNA identification. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafer, H.; Hofacker, I.L. RNAplex: A fast tool for RNA-RNA interaction search. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 2657–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocki, E.P.; Kolbe, D.L.; Eddy, S.R. Infernal 1.0: Inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1335–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiante, V.; Heinekamp, T.; Jain, R.; Hätrl, A.; Brakhage, A.A. The mitogen-activated protein kinase MpkA of Aspergillus fumigatus regulates cell wall signaling and oxidative stress response. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2008, 45, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Deng, Y.Z.; Cui, G.B.; Huang, C.W.; Zhang, B.; Chang, C.Q.; Jiang, Z.D.; Zhang, L.H. The AGC kinase SsAgc1 regulates Sporisorium scitamineum mating/filamentation and pathogenicity. mSphere 2019, 4, e00259-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.D.; Zhao, Y.H.; He, L.M.; Ding, J.F.; Li, B.X.; Mu, W.; Liu, F. Comparison of transcriptome profiles of the fungus Botrytis cinerea and insect pest Bradysia odoriphaga in response to benzothiazole. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.X.; Ma, J.N.; Tian, Y.Y.; Li, X.; Tai, B.W.; Xing, F.G. Fus3 interacts with Gal83, revealing the MAPK crosstalk to Snf1/AMPK to regulate secondary metabolic substrates in Aspergillus flavus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 10065–10075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, J.H.; Bazioli, J.M.; Araújo, E.D.V.; Vendramini, P.H.; Porto, M.C.D.F.; Eberlin, M.N.; Souza-Neto, J.A.; Fill, T.P. Monitoring indole alkaloid production by Penicillium digitatum during infection process in citrus by Mass Spectrometry Imaging and molecular networking. Fungal Biol. 2019, 123, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, É.D.V.; Vendramini, P.H.; Costa, J.H.; Eberlin, M.N.; Montagner, C.C.; Fill, T.P. Determination of try ptoquialanines A and C produced by Penicillium digitatum in orange: Are we safe? Food Chem. 2019, 301, 125285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.Q.; Chen, G.Q.; Liu, X.H.; Dong, B.; Shi, H.B.; Lu, J.P. Crosstalk between SNF1 pathway and the peroxisome mediated lipid metabolism in Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.L.; Lee, T.V.D.; Waalwijk, C.; Diepeningen, A.V.; Brankovics, B.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.S.; Chen, W.Q.; et al. FgPex, a peroxisome biogenesis factor, is involved in regulating vegetative growth, conidiation, sexual development, and virulence in Fusarium graminearum. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.L.; Hao, S.S.; Xu, H.H.; Ji, N.N.; Guo, Y.Y.; Asim, M. Transcriptomics and metabolomics profiling revealed the adaptive mechanism of Penicillium digitatum under modified atmosphere packaging-simulated gas stress. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 219, 113290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, S.Q.; Qin, T.T.; Li, N.; Niu, Y.H.; Li, D.D.; Yuan, Y.Z.; Geng, H.; Xion, L.; Liu, D.L. Whole transcriptome analysis of Penicillium digitatum strains treatmented with prochloraz reveals their drug-resistant mechanisms. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.R.; Yang, Q.Y.; Codana, E.A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.Y. Ultrastructural observation and transcriptome analysis provide insights into mechanisms of Penicillium expansum invading apple wounds. Food Chem. 2023, 414, 135633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.Y.; Gong, W.F.; Tu, T.T.; Zhang, J.Q.; Xia, X.S.; Zhao, L.N.; Zhou, X.H.; Wang, Y. Transcriptome analysis and functional characterization reveal that Peclg gene contributes to the virulence of Penicillium expansum on apple fruits. Foods 2023, 12, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Y.; Li, G.W.; Liu, J.; Wisniewski, M.; Droby, S.; Levin, E.; Huang, S.X.; Liu, Y.S. Multiple transcriptomic analyses and characterization reveal their differential roles in fungal growth and pathogenicity in Penicillium expansum. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2020, 295, 1415–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.F.; Yu, Q.R.; Pan, J.J.; Wang, J.J.; Tang, Z.X.; Bai, X.L.; Shi, L.E.; Zhou, T. The identification and comparative analysis of non-coding RNAs in spores and mycelia of Penicillium expansum. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.L.; Liu, Z.J.; Li, M.X.; Hu, Y.Y.; Yang, L.; Song, X.; Qin, Y.Q. Drafting Penicillium oxalicum calcineurin-CrzA pathway by combining the analysis of phenotype, transcriptome, and endogenous protein–protein interactions. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2022, 158, 103652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.N.; Peng, Y.P.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, X.F.; Yang, Q.Y.; Apaliya, M.T.; Zhang, H.Y. Integration of transcriptome and proteome data reveals ochratoxin A biosynthesis regulated by pH in Penicillium citrinum. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 46767–46777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.K.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.G.; Ying, S.H. Transcriptomic insights into the physiological aspects of the saprotrophic gungus Penicillium citrinum during the spoilage of tobacco leaves. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 18, 1776–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.F.; Cao, Q.W.; Li, N.; Liu, D.L.; Yang, Y.Z. Transcriptome analysis of fungicide responsive gene expression profiles in two Penicillium italicum strains with different response to the sterol demethylation inhibitor (DMI) fungicide prochloraz. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, B.; Kumar, A.; Mehta, S.; Sheoran, N.; Chinnusamy, V.; Prakash, G. Hybrid de novo genome-reassembly reveals new insights on pathways and pathogenicity determinants in rice blast pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae RMg_DI. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majima, H.; Arai, T.; Kusuya, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Watanabe, A.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kamei, K. Genetic differences between Japan and other countries in cyp51A polymorphisms of Aspergillus fumigatus. Mycoses 2021, 64, 1354–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.H.; Chen, M.; Lin, L.Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, D.; Norvienyeku, J.; Zheng, H.K.; Wang, Z.H. Genetic variation bias toward noncoding regions and secreted proteins in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. mSystems 2020, 5, e00346-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, J.L.; Idnurm, A.; Wouw, A.P.D. Genome-wide mapping in an international isolate collection identifies a transcontinental erg11/CYP51 promoter insertion associated with fungicide resistance in Leptosphaeria maculans. Plant Pathol. 2024, 73, 1506–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, K.A.; Hoskins, A.A. Mechanisms and regulation of spliceosome-mediated pre-mRNA splicing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. WIREs RNA 2024, 15, e1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.F.; Dong, F.Y.; Wang, R.X.; Ajmal, M.; Liu, X.Y.; Lin, H.; Chen, H.G. Alternative splicing analysis of lignocellulose-degrading enzyme genes and enzyme variants in Aspergillus niger. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.N.; Wang, P.; Li, X.C.; Pei, Y.K.; Sun, Y.; Ma, X.W.; Ge, X.Y.; Zhu, Y.T.; Li, F.G.; Hou, Y.X. Long non-coding RNAs profiling in pathogenesis of Verticillium dahiae: New insights in the host-pathogen interaction. Plant Sci. 2022, 314, 111098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davati, N.; Ghorbani, A. Discovery of long non-coding RNAs in Aspergillus flavus response to water activity, CO2 concentration, and temperature changes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.J.; Ding, G.J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Wang, X.L.; Wang, D.; Lu, P. Genome-wide identification of long non-coding RNA for Botrytis cinerea during infection to tomato (Solanum lycopersium) leaves. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacko, N.; Lin, X.R. Non-coding RNAs in the development and pathogenesis of eukaryotic microbes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 7989–7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, F.P.; Raimondi, I.; Huarte, M. The multidimensional mechanisms of long noncoding RNA function. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, F.; Mendell, J.T. Functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell 2018, 172, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.Y.; Yin, Z.Y.; Hu, Z.H.; Zhang, K.Q. An overview on identification and regulatory mechanisms of long non-coding RNAs in fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 638617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, G.; Jeon, J.; Lee, H.; Zhou, S.X.; Lee, Y.H. Genome-wide profiling of long non-coding RNA of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae during infection. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.Z.; Chen, Y.J.; Cai, C.L.; Peng, H.J.; Wang, X.Y.; Li, P.; Gu, A.; Li, Y.L.; Ma, D.F. An antisense long non-coding RNA, lncRsn, is involved in sexual reproduction and full virulence in Fusarium graminearum. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Pan, X.M.; Yu, R.; Sheng, Y.T.; Zhang, H.X. Genome-wide identification of long non-coding RNAs reveals potential association with Phytophthora infestans asexual and sexual development. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e01998-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ye, W.; Wang, Y.C. Genome-wide identification of long non-coding RNAs suggests a potential association with effector gene transcription in Phytophthora sojae. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zeng, W.P.; Xie, J.T.; Fu, Y.P.; Jiang, D.H.; Lin, Y.; Chen, W.D.; Cheng, J.S. A novel antisense long non-coding RNA participates in asexual and sexual reproduction by regulating the expression of GzmetE in Fusarium graminearum. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 4939–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zeng, W.P.; Cheng, J.S.; Xie, J.T.; Fu, Y.P.; Jiang, D.H.; Lin, Y. lncRsp1, a long noncoding RNA, influences Fgsp1 expression and sexual reproduction in Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.Y.; Miguel-Rojas, C.; Wang, J.; Townsend, J.P.; Trail, F. Developmental dynamics of long noncoding RNA expression during sexual fruiting body formation in Fusarium graminearum. mBio 2018, 9, e01292-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Rivero, O.; Pardo-Medina, J.; Gutiérrez, G.; Limón, M.C.; Avalos, J. A novel lncRNA as positive regulator of carotenoid biosynheisis in Fusarium. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.G.; Yang, J.; Peng, J.B.; Cheng, Z.H.; Liu, X.S.; Zhang, Z.D.; Bhadauria, V.; Zhao, W.S.; Peng, Y.L. Transcriptional landscapes of long non-coding RNAs and alternative splicing in Pyricularia oryzae revealed by RNA-seq. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 723636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.Z.; Ibrahim, H.M.M.; Erz, M.; Kümmel, F.; Panstruga, R.; Kusch, S. Long noncoding RNAs emerge from transposon-derived antisense sequences and may contribute to infection stage-specific transposon regulation in a fungal phytopathogen. Mob. DNA 2023, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.J.; Wu, Y.W.; Deng, S.J.; Lei, X.Y.; Yang, X.Y. Emerging role of noncoding RNAs in human cancers. Discov. Oncol. 2023, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.L.; Takenaka, K.; Xu, S.M.; Cheng, Y.N.; Janita, M. Recent advances in investigation of circRNA/lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks through RNA sequencing data analysis. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2025, 24, elaf005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, F.; Liang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, H.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Lai, T. Transcriptomic Profiling of mRNA and lncRNA During the Developmental Transition from Spores to Mycelia in Penicillium digitatum. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122879

Zhou T, Yang Y, Wang F, Liang L, Zhang Z, Dong H, Jiang Z, Zhang P, Lai T. Transcriptomic Profiling of mRNA and lncRNA During the Developmental Transition from Spores to Mycelia in Penicillium digitatum. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122879

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Ting, Yajie Yang, Fei Wang, Linqian Liang, Ziqi Zhang, Heru Dong, Zhaocheng Jiang, Pengcheng Zhang, and Tongfei Lai. 2025. "Transcriptomic Profiling of mRNA and lncRNA During the Developmental Transition from Spores to Mycelia in Penicillium digitatum" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122879

APA StyleZhou, T., Yang, Y., Wang, F., Liang, L., Zhang, Z., Dong, H., Jiang, Z., Zhang, P., & Lai, T. (2025). Transcriptomic Profiling of mRNA and lncRNA During the Developmental Transition from Spores to Mycelia in Penicillium digitatum. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122879