Culture-Dependent Bioprospecting of Halophilic Microorganisms from Portuguese Salterns

Abstract

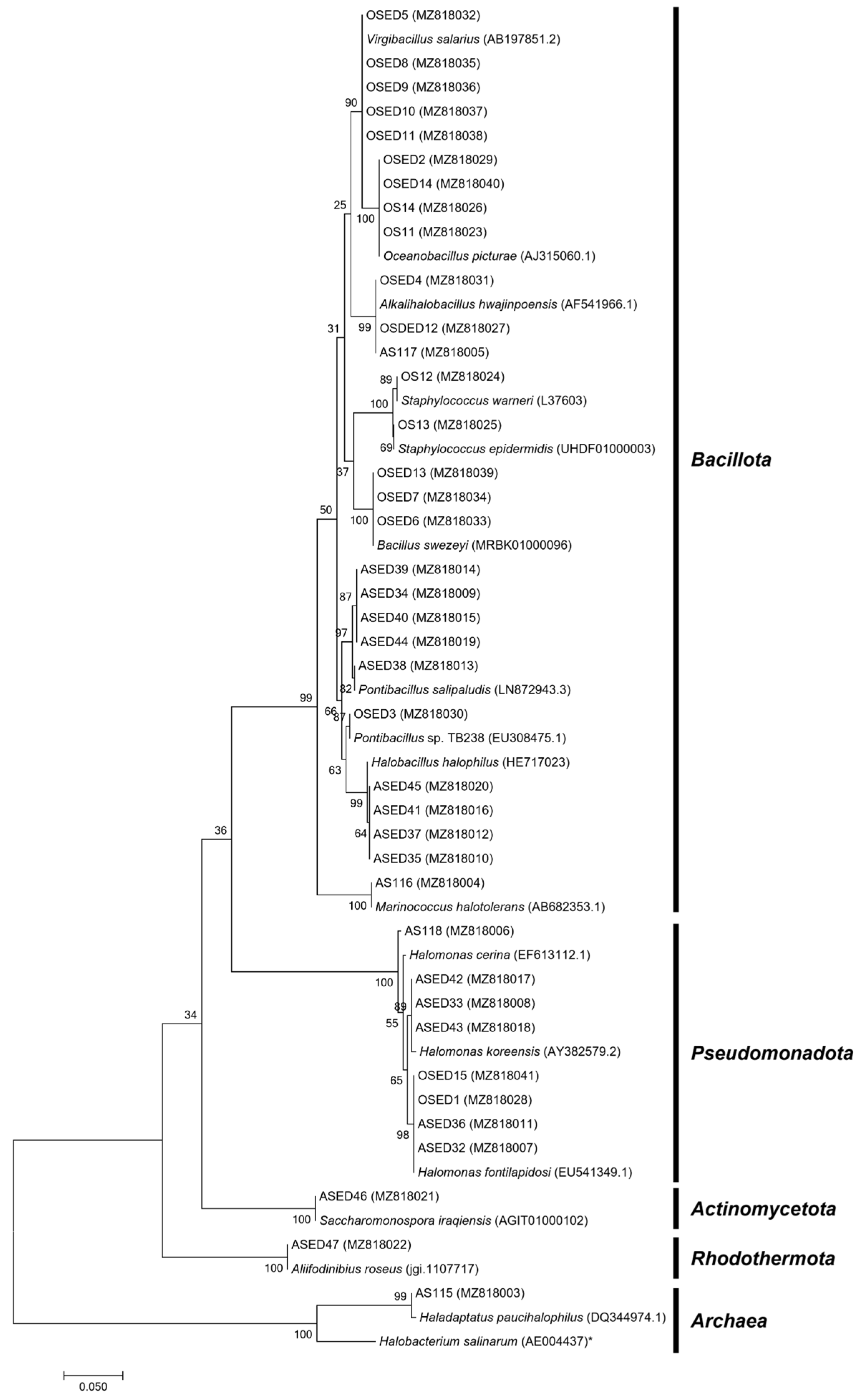

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Microbial Isolation

2.2. Bacterial DNA Extraction

2.3. Microbial Identification

2.4. Dereplication of Strains Affiliated with the Same Species

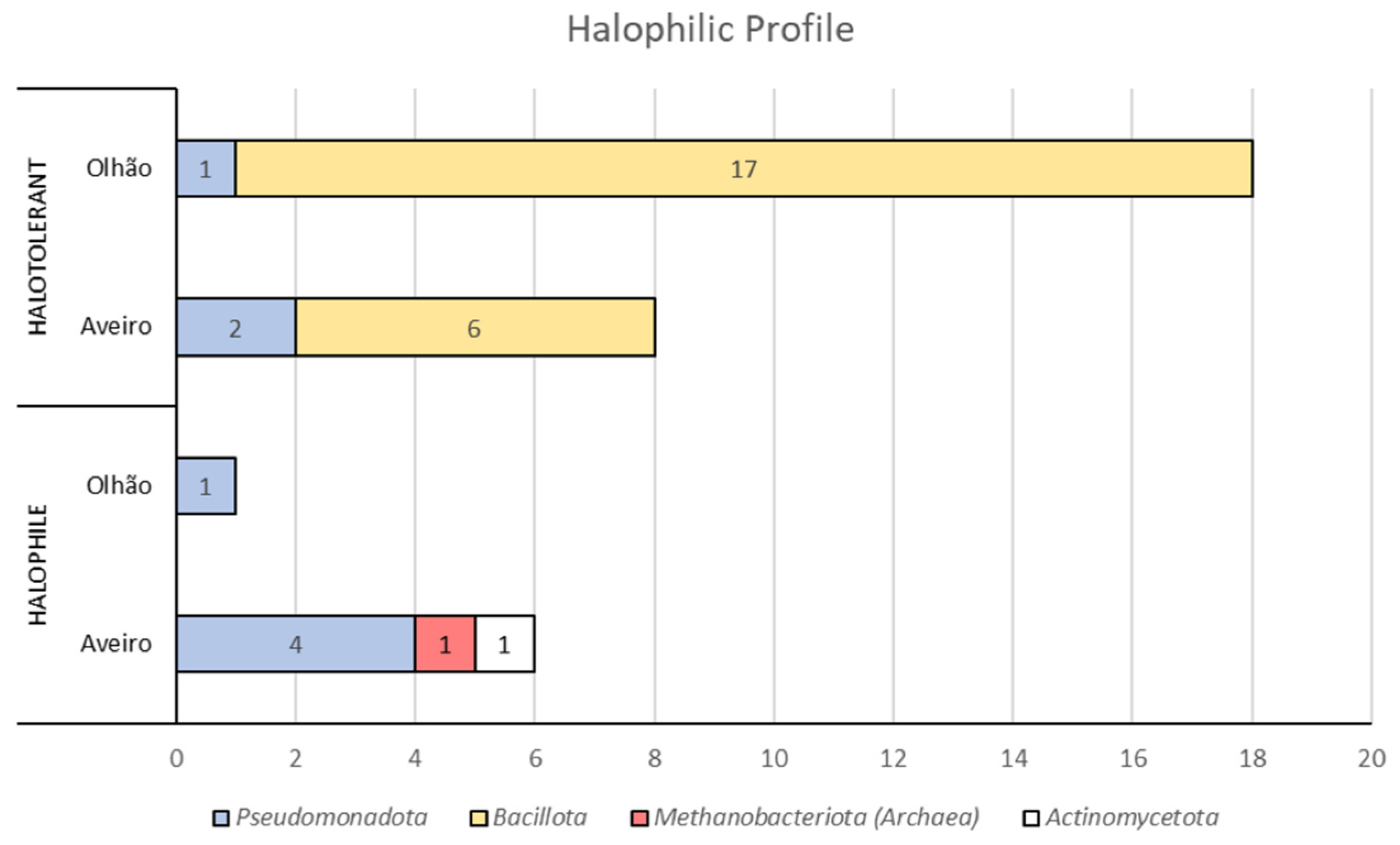

2.5. Isolates’ Halophilic Profiles

2.6. Isolates’ Bioactive Potentials

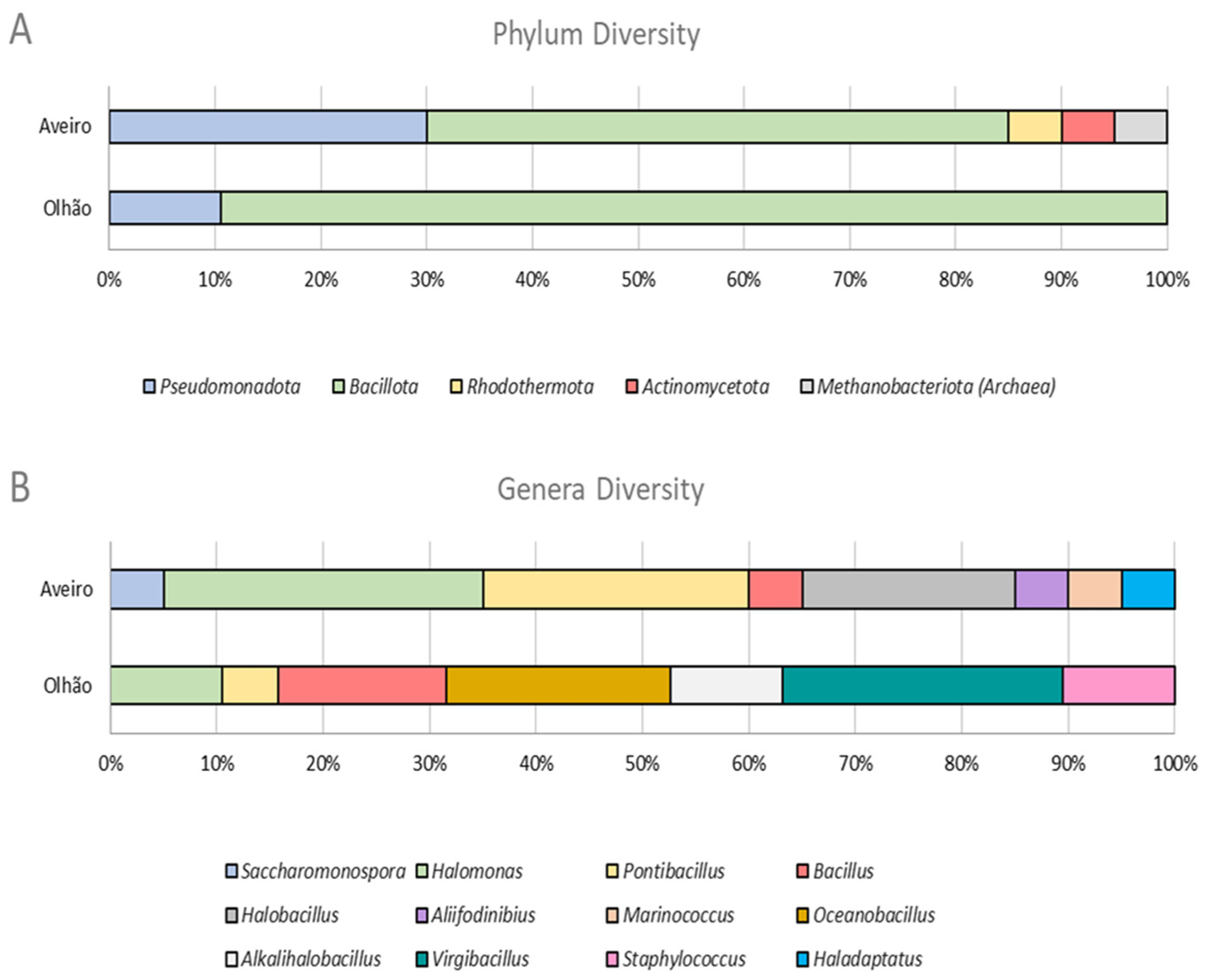

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NRPS | Non-ribosomal Peptide Synthetase |

| PKS | Polyketide Synthase |

| NPs | Natural Products |

| ERIC | Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus |

| BOX | Box Repetitive Extragenic Palindromic |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| KS | β-ketosynthase |

References

- Ma, Y.; Galinski, E.A.; Grant, W.D.; Oren, A.; Ventosa, A. Halophiles 2010: Life in Saline Environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 6971–6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozegar, M.A.; Safarpour, A.; Noghabi, K.A.; Bakhtiary, T.; Ventosa, A. Halophiles and Their Vast Potential in Biofuel Production. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, K.J.; Mesbah, N.M.; Wiegel, J. Biodiversity of poly-extremophilic Bacteria: Does combining the extremes of high salt, alkaline pH and elevated temperature approach a physico-chemical boundary for life? Saline Syst. 2009, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Quintanilla, G.; Millet, O. On the Molecular Basis of the Hypersaline Adaptation of Halophilic Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 169439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtenay, E.S.; Capp, M.W.; Anderson, C.F.; Record, M.T., Jr. Vapor Pressure Osmometry Studies of Osmolyte−Protein Interactions: Implications for the Action of Osmoprotectants in Vivo and for the Interpretation of “Osmotic Stress” Experiments in Vitro. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 4455–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinisch, L.; Kirchner, I.; Grimm, M.; Kühner, S.; Pierik, A.J.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Filker, S. Glycine Betaine and Ectoine Are the Major Compatible Solutes Used by Four Different Halophilic Heterotrophic Ciliates. Microb. Ecol. 2019, 77, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventosa, A.; Nieto, J.J.; Oren, A. Biology of Moderately Halophilic Aerobic Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998, 62, 504–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, P.; Amoozegar, M.A.; Ventosa, A. Halophiles and Their Biomolecules: Recent Advances and Future Applications in Biomedicine. Mar. Drugs 2019, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathakrishnan, D.; Gopalan, A.K. Isolation and characterization of halophilic isolates from Indian salterns and their screening for production of hydrolytic enzymes. Environ. Chall. 2022, 6, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, S.; Bunk, B.; Spröer, C.; Rohde, M.; Klenk, H.-P. Genome biology of a novel lineage of planctomycetes widespread in anoxic aquatic environments. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 2438–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nespoli, C.R. Characterization of Extreme Halophilic Prokaryotic Consortia of a Traditional Solar Saltern in Olhão. Master Thesis, Universidade do Algarve, Algarve, Portugal, 2009. Available online: https://sapientia.ualg.pt/entities/publication/15bc6c3f-0b21-4ae0-8264-fd06f554d206 (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Filker, S.; Gimmler, A.; Dunthorn, M.; Mahé, F.; Stoeck, T. Deep sequencing uncovers protistan plankton diversity in the Portuguese Ria Formosa solar saltern ponds. Extremophiles 2015, 19, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filker, S.; Forster, D.; Weinisch, L.; Mora-Ruiz, M.; González, B.; Farías, M.E.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Stoeck, T. Transition boundaries for protistan species turnover in hypersaline waters of different biogeographic regions. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 3186–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradel, N.; Fardeau, M.-L.; Tindall, B.J.; Spring, S. Anaerohalosphaera lusitana gen. nov., sp. nov., and Limihaloglobus sulfuriphilus gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from solar saltern sediments, and proposal of Anaerohalosphaeraceae fam. nov. within the order Sedimentisphaerales. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, H.; Dundas, I.D. Rhodospirillum salinarum sp. nov., a halophilic photosynthetic bacterium isolated from a Portuguese saltern. Arch. Microbiol. 1984, 138, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Haridon, S.; Corre, E.; Guan, Y.; Vinu, M.; La Cono, V.; Yakimov, M.; Stingl, U.; Toffin, L.; Jebbar, M. Complete Genome Sequence of the Halophilic Methylotrophic Methanogen Archaeon Methanohalophilus portucalensis Strain FDF-1T. Genome Announc. 2018, 6, e01482-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, E.; Dias, T.V.; Ferraz, G.; Carvalho, M.F.; Lage, O.M. Culturable bacteria from two Portuguese salterns: Diversity and bioactive potential. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, E.; Carvalho, M.F.; Lage, O.M. Culturomics remains a highly valuable methodology to obtain rare microbial diversity with putative biotechnological potential from two Portuguese salterns. Front. Biosci. 2022, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Hermoso, C.; de la Haba, R.R.; Sánchez-Porro, C.; Ventosa, A. Salinivibrio kushneri sp. nov., a moderately halophilic bacterium isolated from salterns. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 41, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics; Stackebrandt, E., Goodfellow, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- Gantner, S.; Andersson, A.F.; Alonso-Sáez, L.; Bertilsson, S. Novel primers for 16S rRNA-based archaeal community analyses in environmental samples. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 84, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.-H.; Ha, S.-M.; Kwon, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H.; Chun, J. Introducing EzBioCloud: A taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versalovic, J.; Schneider, M.; De Bruijn, F.J.; Lupski, J.R. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol. Cell Biol. 1994, 5, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Versalovic, J.; Koeuth, T.; Lupski, R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to finerpriting of bacterial enomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19, 6823–6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.K.; Garson, M.J.; Fuerst, J.A. Marine actinomycetes related to the “Salinospora” group from the Great Barrier Reef sponge Pseudoceratina clavata. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilan, B.A.; Dittmann, E.; Rouhiainen, L.; Bass, R.A.; Schaub, V.; Sivonen, K.; Börner, T. Nonribosomal peptide synthesis and toxigenicity of cyanobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 4089–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, A.P.; Viana, F.; Bondoso, J.; Correia, M.I.; Gomes, L.; Humanes, M.; Reis, A.; Xavier, J.R.; Gaspar, H.; Lage, O.M. The antimicrobial activity of heterotrophic bacteria isolated from the marine sponge Erylus deficiens (Astrophorida, Geodiidae). Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruginescu, R.; Gomoiu, I.; Popescu, O.; Cojoc, R.; Neagu, S.; Lucaci, I.; Batrinescu-Moteau, C.; Enache, M. Bioprospecting for Novel Halophilic and Halotolerant Sources of Hydrolytic Enzymes in Brackish, Saline and Hypersaline Lakes of Romania. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, K.N.; Krumholz, L.R.; Oren, A.; Elshahed, M.S. Haladaptatus paucihalophilus gen. nov., sp. nov., a halophilic archaeon isolated from a low-salt, sulfide-rich spring. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, K.J.; Cresswell-Maynard, T.D.; Nedwell, D.B.; McGenity, T.J.; Grant, W.D.; Timmis, K.N.; Embley, T.M. Isolation of haloarchaea that grow at low salinities. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-X.; Liu, J.-H.; Xiao, W.; Ma, X.-L.; Lai, Y.-H.; Li, Z.-Y.; Ji, K.-Y.; Wen, M.-L.; Cui, X.-L. Aliifodinibius roseus gen. nov., sp. nov., and Aliifodinibius sediminis sp. nov., two moderately halophilic bacteria isolated from salt mine samples. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 2907–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, J.-S.; Al-Tai, A.M.; Zhou, Z.-H.; Qu, L.-H. Actinopolyspora iraqiensis sp. nov., a New Halophilic Actinomycete Isolated from Soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1994, 44, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baati, H.; Amdouni, R.; Gharsallah, N.; Sghir, A.; Ammar, E. Isolation and Characterization of Moderately Halophilic Bacteria from Tunisian Solar Saltern. Curr. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, R.; Pašić, L.; Fernández, A.B.; Martin-Cuadrado, A.-B.; Mizuno, C.M.; McMahon, K.D.; Papke, R.T.; Stepanauskas, R.; Rodriguez-Brito, B.; Rohwer, F.; et al. New Abundant Microbial Groups in Aquatic Hypersaline Environments. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueriaghli, N.; González-Domenech, C.M.; Martínez-Checa, F.; Muyzer, G.; Ventosa, A.; Quesada, E.; Béjar, V. Diversity and distribution of Halomonas in Rambla Salada, a hypersaline environment in the southeast of Spain. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 87, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyadzhieva, I.; Tomova, I.; Radchenkova, N.; Kambourova, M.; Poli, A.; Vasileva-Tonkova, E. Diversity of Heterotrophic Halophilic Bacteria Isolated from Coastal Solar Salterns, Bulgaria and Their Ability to Synthesize Bioactive Molecules with Biotechnological Impact. Microbiology 2018, 87, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, U.; Mukhopadhyay, S.K. Microbial community composition of saltern soils from Ramnagar, West Bengal, India. Ecol. Genet. Genom. 2019, 12, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.-W.; Lin, Y.-J.; Ou, M.-Y.; Chen, K.-B. Isolation and diversity of sediment bacteria in the hypersaline aiding lake, China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Domenech, C.M.; Martínez-Checa, F.; Quesada, E.; Béjar, V. Halomonas fontilapidosi sp. nov., a moderately halophilic, denitrifying bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 1290–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.-M.; Yoon, J.-H.; Lee, J.-C.; Jeon, C.O.; Park, D.-J.; Sung, C.; Kim, C.-J. Halomonas koreensis sp. nov., a novel moderately halophilic bacterium isolated from a solar saltern in Korea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 2037–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Domenech, C.M.; Martínez-Checa, F.; Quesada, E.; Béjar, V. Halomonas cerina sp. nov., a moderately halophilic, denitrifying, exopolysaccharide-producing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. Updating the 97% identity threshold for 16S ribosomal RNA OTUs. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2371–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, G.; Bu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Lin, X. Phylogenetic analysis and screening of antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of moderately halophilic bacteria isolated from the Weihai Solar Saltern (China). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.-H.; Kim, I.-G.; Kang, K.H.; Oh, T.-K.; Park, Y.-H. Bacillus hwajinpoensis sp. nov. and an unnamed Bacillus genomospecies, novel members of Bacillus rRNA group 6 isolated from sea water of the East Sea and the Yellow Sea in Korea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlap, C.A.; Schisler, D.A.; Perry, E.B.; Connor, N.; Cohan, F.M.; Rooney, A.P. Bacillus swezeyi sp. nov. and Bacillus haynesii sp. nov., isolated from desert soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 2720–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, D.; Fahmy, F.; Rolf, H.; Tosunoglu, N. Sporosarcina halophila sp. nov., an Obligate, Slightly Halophilic Bacterium from Salt Marsh Soils. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1983, 4, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventosa, A.; Fernández, A.B.; León, M.J.; Sánchez-Porro, C.; Rodriguez-Valera, F. The Santa Pola saltern as a model for studying the microbiota of hypersaline environments. Extremophiles 2014, 18, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiamis, G.; Katsaveli, K.; Ntougias, S.; Kyrpides, N.; Andersen, G.; Piceno, Y.; Bourtzis, K. Prokaryotic community profiles at different operational stages of a Greek solar saltern. Res. Microbiol. 2008, 159, 609–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghoni, A.; Emtiazi, G.; Amoozegar, M.A.; Cretoiu, M.S.; Stal, L.J.; Etemadifar, Z.; Fazeli, S.A.S.; Bolhuis, H. Microbial diversity in the hypersaline Lake Meyghan, Iran. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyrman, J.; Logan, N.A.; Busse, H.-J.; Balcaen, A.; Lebbe, L.; Rodriguez-Diaz, M.; Swings, J.; De Vos, P. Virgibacillus carmonensis sp. nov., Virgibacillus necropolis sp. nov. and Virgibacillus picturae sp. nov., three novel species isolated from deteriorated mural paintings, transfer of the species of the genus Salibacillus to Virgibacillus, as Virgibacillus marismortui comb. nov. and Virgibacillus salexigens comb. nov., and emended description of the genus Virgibacillus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, N.-P.; Hamza-Chaffai, A.; Vreeland, R.H.; Isoda, H.; Naganuma, T. Virgibacillus salarius sp. nov., a halophilic bacterium isolated from a Saharan salt lake. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 2409–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultanpuram, V.R.; Mothe, T.; Mohammed, F.; Chintalapati, S.; Chintalapati, V.R. Pontibacillus salipaludis sp. nov., a slightly halophilic bacterium isolated from a salt pan. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 3884–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-J.; Schumann, P.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Chen, G.-Z.; Tian, X.-P.; Xu, L.-H.; Stackebrandt, E.; Jiang, C.-L. Marinococcus halotolerans sp. nov., isolated from Qinghai, north-west China. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1801–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, R.; Moran, J.; Horsburgh, M.J. Staphylococci: Colonizers and Pathogens of Human Skin. Futur. Microbiol. 2014, 9, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Du, L.; Liu, F.; Xu, F.; Hu, B.; Venturi, V.; Qian, G. Involvement of both PKS and NRPS in antibacterial activity in Lysobacter enzymogenes OH11. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 355, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zothanpuia; Passari, A.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Singh, B.P. Detection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria endowed with antimicrobial activity from a freshwater lake and their phylogenetic affiliation. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, D.E.; Walsh, C.T. The parallel and convergent universes of polyketide synthases and nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chem. Biol. 1999, 6, R319–R325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Baker, P.; Piper, C.; Cotter, P.D.; Walsh, M.; Mooij, M.J.; Bourke, M.B.; Rea, M.C.; O’connor, P.M.; Ross, R.P.; et al. Isolation and Analysis of Bacteria with Antimicrobial Activities from the Marine Sponge Haliclona simulans Collected from Irish Waters. Mar. Biotechnol. 2009, 11, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fewer, D.P.; Holm, L.; Rouhiainen, L.; Sivonen, K. Atlas of nonribosomal peptide and polyketide biosynthetic pathways reveals common occurrence of nonmodular enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9259–9264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, H.; Sonnenschein, E.C.; Melchiorsen, J.; Gram, L. Genome mining reveals unlocked bioactive potential of marine Gram-negative bacteria. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoutzias, G.D.; Chaliotis, A.; Mossialos, D. Discovery Strategies of Bioactive Compounds Synthesized by Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases and Type-I Polyketide Synthases Derived from Marine Microbiomes. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Checa, F.; Toledo, F.; Vilchez, R.; Quesada, E.; Calvo, C. Yield production, chemical composition, and functional properties of emulsifier H28 synthesized by Halomonas eurihalina strain H-28 in media containing various hydrocarbons. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 58, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, S.; del Moral, A.; Ferrer, M.R.; Tallon, R.; Quesada, E.; Béjar, V. Mauran, an exopolysaccharide produced by the halophilic bacterium Halomonas maura, with a novel composition and interesting properties for biotechnology. Extremophiles 2003, 7, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J.A.; Béjar, V.; Llamas, I.; Arias, S.; Bressollier, P.; Tallon, R.; Urdaci, M.C.; Quesada, E. Exopolysaccharides produced by the recently described halophilic bacteria Halomonas ventosae and Halomonas anticariensis. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, I.; Béjar, V.; Martínez-Checa, F.; Martínez-Cánovas, M.J.; Molina, I.; Quesada, E. Halomonas stenophila sp. nov., a halophilic bacterium that produces sulphate exopolysaccharides with biological activity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 2508–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margesin, R.; Schinner, F. Potential of halotolerant and halophilic microorganisms for biotechnology. Extremophiles 2001, 5, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, M.T.; Mellado, E.; Ostos, J.C.; Ventosa, A. Halomonas organivorans sp. nov., a moderate halophile able to degrade aromatic compounds. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1723–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fickers, P. Antibiotic Compounds from Bacillus: Why are they so Amazing? Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 8, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, K.J.; Bleich, R.M.; Maria, K.C.S.; Allen, S.E.; Farag, S.; Team, A.; Shank, E.A.; Bowers, A.A. Large-Scale Bioinformatics Analysis of Bacillus Genomes Uncovers Conserved Roles of Natural Products in Bacterial Physiology. mSystems 2017, 2, e00040-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, C.R.; Mouillon, J.-M.; Pohl, S.; Arnau, J. Secondary metabolite production and the safety of industrially important members of the Bacillus subtilis group. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A. Industrial and environmental applications of halophilic microorganisms. Environ. Technol. 2010, 31, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varrella, S.; Tangherlini, M.; Corinaldesi, C. Deep Hypersaline Anoxic Basins as Untapped Reservoir of Polyextremophilic Prokaryotes of Biotechnological Interest. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemzahi, A.; Makhkdoumi, A.; Asoodeh, A. Culturable diversity and enzyme production survey of halophilic prokaryotes from a solar saltern on the shore of the Oman Sea. J. Genet. Resour. 2020, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolate | Phylum | Genus | % NaCl Range | BOX-PCR Pattern a | ERIC-PCR Pattern a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS115 | Euryarchaeota (Archaea) | Haladaptatus | 8 to 25 | ND | ND |

| ASED46 | Actinomycetota | Saccharomonospora | 3 to 13 | ND | ND |

| OSED4 | Bacillota | Alkalihalobacillus | 0 to 13 | g | G |

| OSED12 | Bacillota | Alkalihalobacillus | 0 to 20 | h | H |

| AS117 | Bacillota | Alkalihalobacillus | 0 to 20 | i | I |

| OSED13 | Bacillota | Bacillus | 0 to 13 | j | J |

| OSED6 | Bacillota | Bacillus | 0 to 13 | j | J |

| OSED7 | Bacillota | Bacillus | 0 to 13 | j | J |

| ASED35 | Bacillota | Halobacillus | ND | s | S |

| ASED37 | Bacillota | Halobacillus | ND | s | S |

| ASED45 | Bacillota | Halobacillus | 0 to 35 | s | α |

| ASED41 | Bacillota | Halobacillus | ND | t | S |

| AS116 | Bacillota | Marinococcus | 0 to 25 | ND | ND |

| OS11 | Bacillota | Oceanobacillus | 0 to 13 | d | D |

| OSED2 | Bacillota | Oceanobacillus | 0 to 13 | d | Y |

| OSED14 | Bacillota | Oceanobacillus | 0 to 13 | e | E |

| OS14 | Bacillota | Oceanobacillus | 0 to 20 | f | F |

| ASED39 | Bacillota | Pontibacillus | 0 to 25 | k | K |

| ASED34 | Bacillota | Pontibacillus | 0 to 25 | l | L |

| ASED40 | Bacillota | Pontibacillus | ND | m | M |

| ASED44 | Bacillota | Pontibacillus | 0 to 8 | n | N |

| ASED38 | Bacillota | Pontibacillus | ND | o | O |

| OSED3 | Bacillota | Pontibacillus | 0 to 13 | ND | ND |

| OS13 | Bacillota | Staphylococcus | 0 to 8 | ND | ND |

| OS12 | Bacillota | Staphylococcus | 0 to 13 | ND | ND |

| OSED5 | Bacillota | Virgibacillus | 0 to 13 | a | A |

| OSED10 | Bacillota | Virgibacillus | 0 to 13 | b | B |

| OSED8 | Bacillota | Virgibacillus | 0 to 13 | b | B |

| OSED9 | Bacillota | Virgibacillus | 0 to 13 | b | Z |

| OSED11 | Bacillota | Virgibacillus | 0 to 13 | c | C |

| ASED42 | Pseudomonadota | Halomonas | 3 to 20 | p | P |

| ASED33 | Pseudomonadota | Halomonas | 0 to 20 | p | P |

| ASED43 | Pseudomonadota | Halomonas | 0 to 20 | q | Q |

| OSED15 | Pseudomonadota | Halomonas | 0 to 20 | u | U |

| OSED1 | Pseudomonadota | Halomonas | 3 to 20 | v | V |

| ASED36 | Pseudomonadota | Halomonas | 3 to 20 | w | W |

| ASED32 | Pseudomonadota | Halomonas | 3 to 20 | x | X |

| AS118 | Pseudomonadota | Halomonas | 3 to 20 | ND | ND |

| ASED47 | Rhodothermaeota | Aliifodinibius | ND | ND | ND |

| Phylum | Genus | Total Number of Isolates | Only PKS-I | Only NRPS | Both |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinomycetota | Saccharomonospora | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pseudomonadota | Halomonas | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Bacillota | Pontibacillus | 6 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Halobacillus | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Marinococcus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Bacillus | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Oceanobacillus | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Alkalihalobacillus | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Virgibacillus | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Staphylococcus | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Rhodothermaeota | Aliifodinibius | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Euryarchaeota (Archaea) | Haladaptatus | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almeida, E.; Jackiewicz, A.; Carvalho, M.d.F.; Lage, O.M. Culture-Dependent Bioprospecting of Halophilic Microorganisms from Portuguese Salterns. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122867

Almeida E, Jackiewicz A, Carvalho MdF, Lage OM. Culture-Dependent Bioprospecting of Halophilic Microorganisms from Portuguese Salterns. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122867

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmeida, Eduarda, Adrianna Jackiewicz, Maria de Fátima Carvalho, and Olga Maria Lage. 2025. "Culture-Dependent Bioprospecting of Halophilic Microorganisms from Portuguese Salterns" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122867

APA StyleAlmeida, E., Jackiewicz, A., Carvalho, M. d. F., & Lage, O. M. (2025). Culture-Dependent Bioprospecting of Halophilic Microorganisms from Portuguese Salterns. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122867