MecVax, an Epitope- and Structure-Based Broadly Protective Subunit Vaccine Against Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC)

Abstract

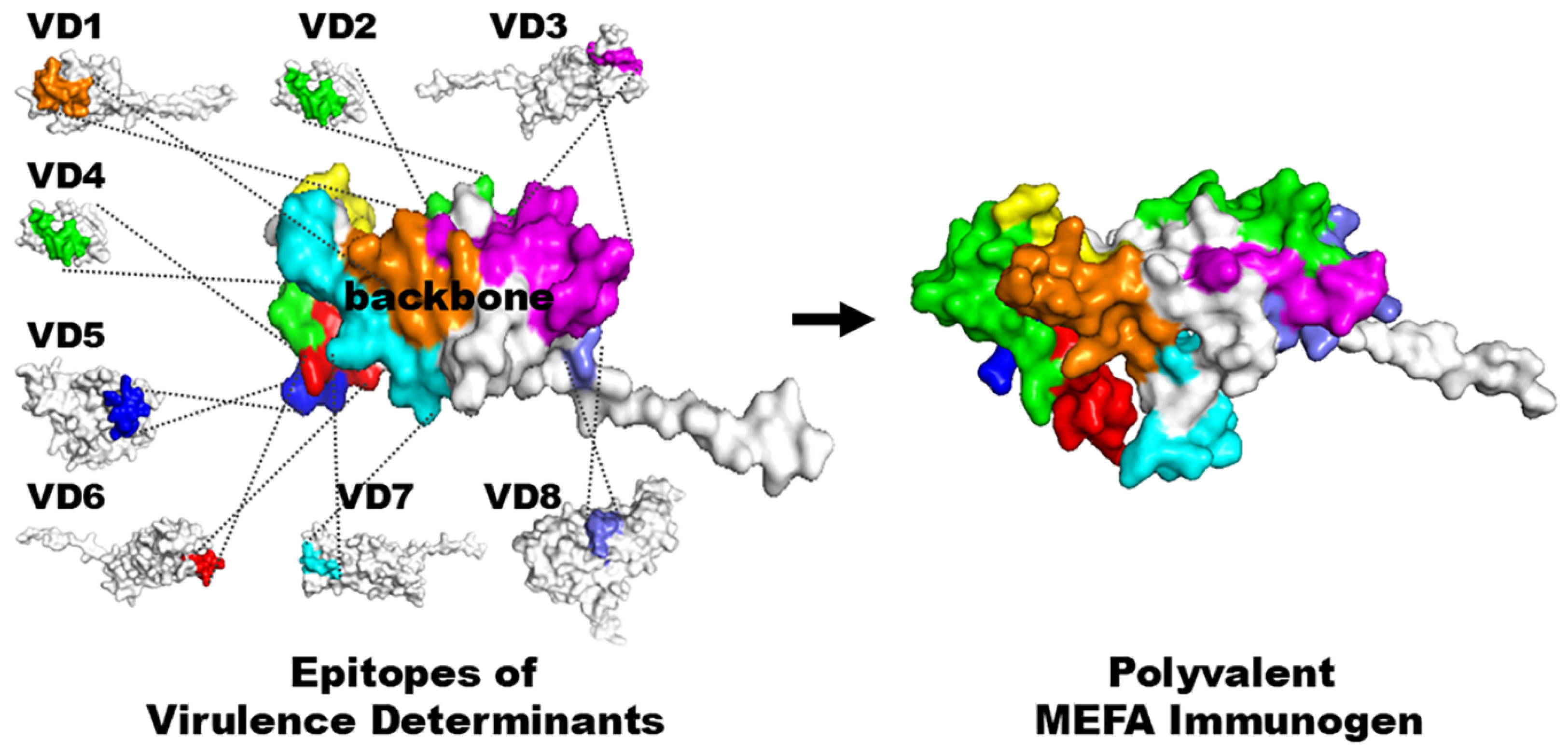

1. Introduction

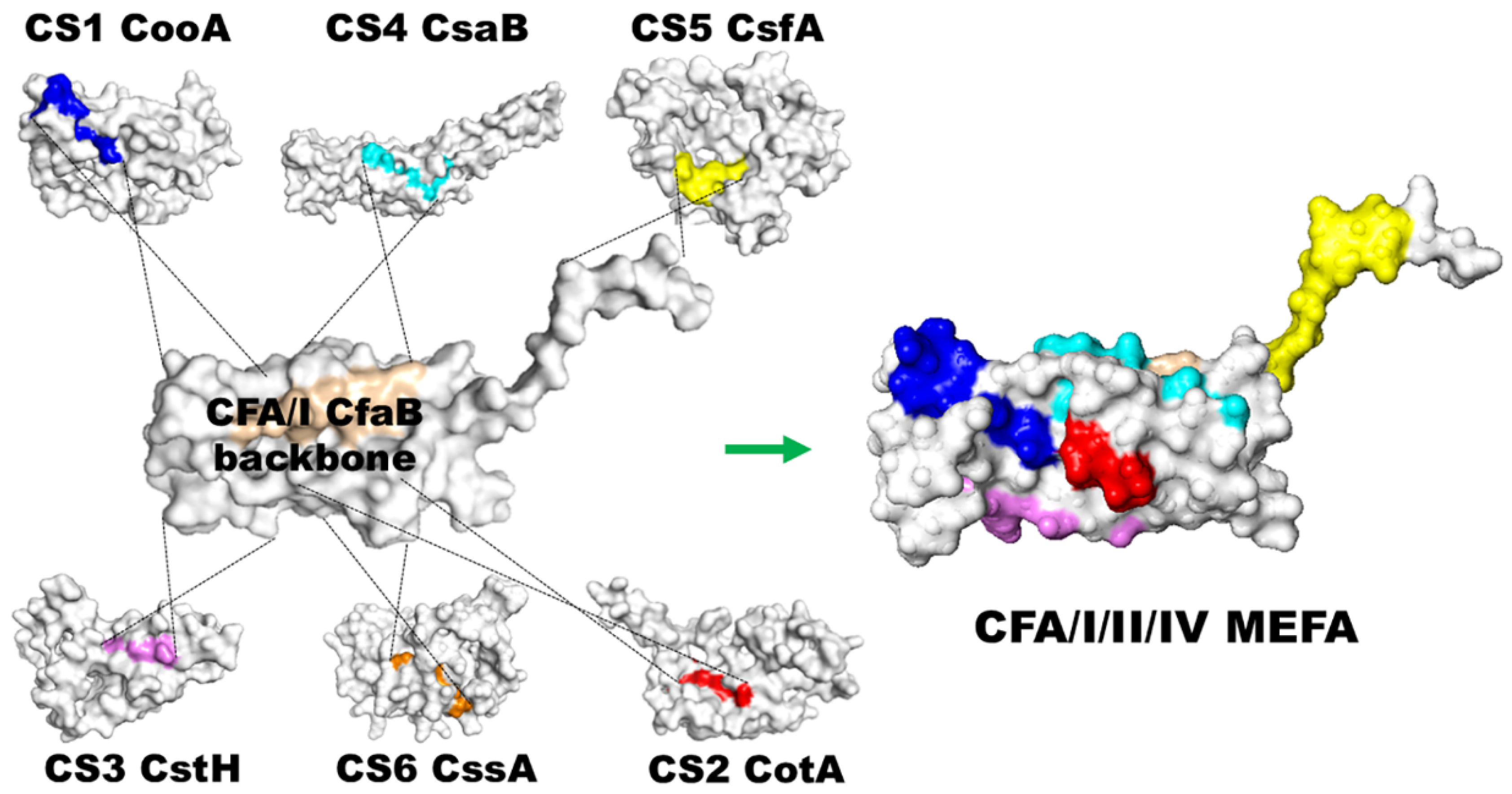

2. CFA/I/II/IV MEFA, a Broadly Immunogenic and Protective ETEC Adhesin Antigen Constructed with a Novel Epitope- and Structure-Based Multiepitope-Fusion-Antigen (MEFA) Platform

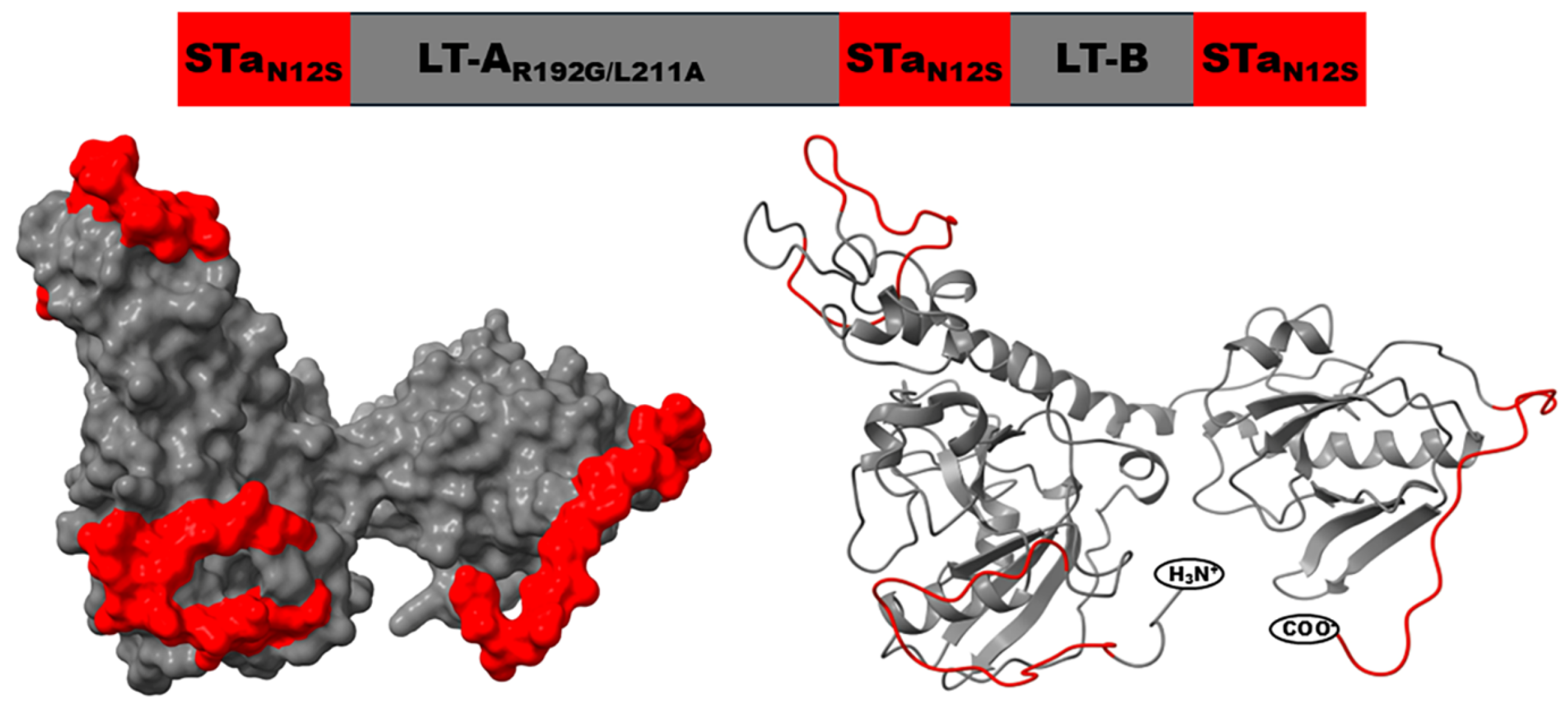

3. Toxoid Fusion 3xSTaN12S-mnLTR192G/L211A, a Nontoxic Toxin Antigen That Induces Neutralizing Antibodies Against ETEC Toxins STa and LT

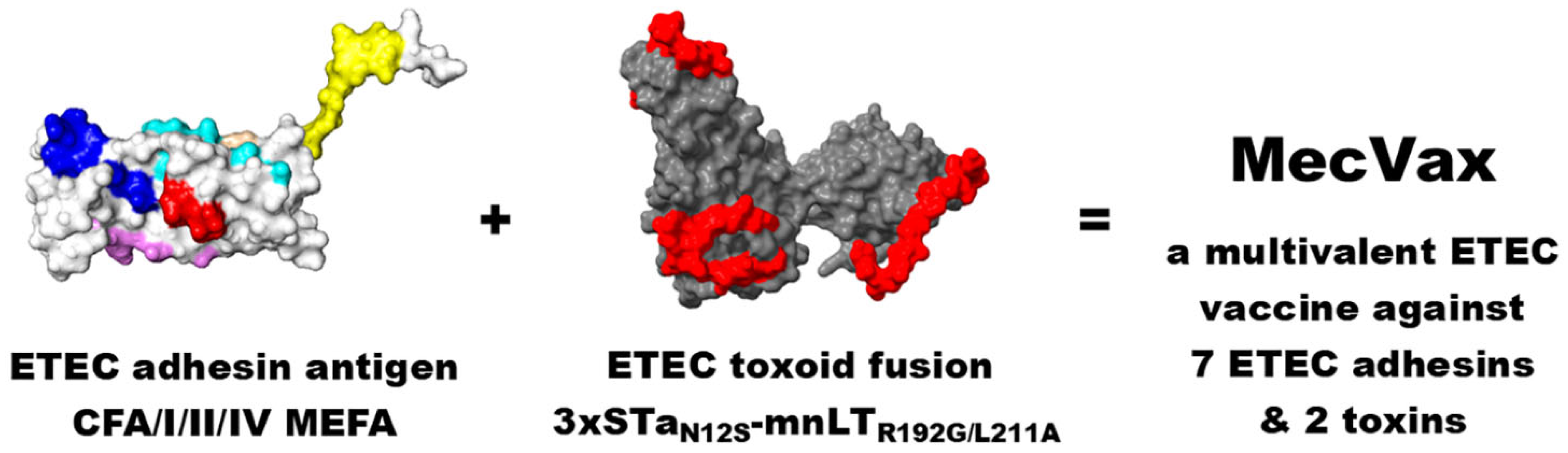

4. MecVax, an ETEC Vaccine Candidate Composed of CFA/I/II/IV MEFA and Toxoid Fusion 3xSTaN12S-mnLTR192G/L211A, for Broad Protection Against ETEC Intestinal Colonization and Clinical Diarrhea

5. MecVax Preclinical Efficacy Can Be Evaluated in a Dual Animal Challenge Model, a Combination of a Rabbit Model Against ETEC Intestinal Colonization and a Pig Passive Protection Model Against ETEC Toxin-Mediated Diarrhea

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ETEC | Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli |

| MEFA | Multiepitope fusion antigen |

| MecVax | Multivalent ETEC vaccine |

| CFA | Colonization factor antigen |

| CS | Coli surface antigen |

| LT | Heat-labile toxin |

| STa | Heat-stable toxin |

| WASH | Water, sanitation, hygiene |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| cGMP | Cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| LTA | Heat-labile toxin A subunit |

| LTB | Heat-labile toxin B subunit |

| GM1 | GM1 gangliosidosis |

| dmLT | Double mutant heat-labile toxin |

| IgG | Immunoglobin G |

| IgA | Immunoglobin A |

| CHIM | Controlled human infection models |

References

- Nataro, J.P.; Kaper, J.B. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 142–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubreuil, J.D.; Isaacson, R.E.; Schifferli, D.M. Animal Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. EcoSal Plus 2016, 7, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K.L.; Nataro, J.P.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Nasrin, D.; Farag, T.H.; Panchalingam, S.; Wu, Y.; Sow, S.O.; Sur, D.; Breiman, R.F.; et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): A prospective, case-control study. Lancet 2013, 382, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platts-Mills, J.A.; Babji, S.; Bodhidatta, L. Pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhoea in developing countries: A multisite birth cohort study (MAL-ED). Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, E527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Begum, Y.A.; Rahman, S.I.A.; Afrad, M.H.; Parvin, N.; Akter, A.; Tauheed, I.; Amin, M.A.; Ryan, E.T.; Khan, A.I.; et al. Age-dependent pathogenic profiles of enterotoxigenic diarrhea in Bangladesh. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1484162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, F.; Islam, M.T.; Ahmmed, F.; Akter, A.; Mwebia, M.B.; Im, J.; Rickett, N.Y.; Mbae, C.K.; Aziz, A.B.; Ongadi, B.; et al. Epidemiological and Clinical Features of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) Diarrhea in an Urban Slum in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.R.; Beeching, N.J. Travelers’ diarrhea. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 23, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.D.; DuPont, H.L. Etiology of travellers’ diarrhea. J. Travel. Med. 2017, 24, S13–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.S.; Mahugu, E.W.; Ashbaugh, H.R.; Wellbrock, A.G.; Nozadze, M.; Shrestha, S.K.; Soto, G.M.; Nada, R.A.; Pandey, P.; Esona, M.D.; et al. Etiology and Epidemiology of Travelers’ Diarrhea among US Military and Adult Travelers, 2018–2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 240308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, M.D.; Pires, S.M.; Black, R.E.; Caipo, M.; Crump, J.A.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Dopfer, D.; Fazil, A.; Fischer-Walker, C.L.; Hald, T.; et al. World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 22 Foodborne Bacterial, Protozoal, and Viral Diseases, 2010: A Data Synthesis. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Allen, C.; Arora, M.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brown, A. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1459–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, I.A.; Troeger, C.; Blacker, B.F.; Rao, P.C.; Brown, A.; Atherly, D.E.; Brewer, T.G.; Engmann, C.M.; Houpt, E.R.; Kang, G.; et al. Morbidity and mortality due to shigella and enterotoxigenic diarrhoea: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2016. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrant, R.L.; Kosek, M.; Moore, S.; Lorntz, B.; Brantley, R.; Lima, A.A. Magnitude and impact of diarrheal diseases. Arch. Med. Res. 2002, 33, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.E.; Cousens, S.; Johnson, H.L.; Lawn, J.E.; Rudan, I.; Bassani, D.G.; Jha, P.; Campbell, H.; Walker, C.F.; Cibulskis, R.; et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2010, 375, 1969–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Gastroenterology Organization. Acute Diarrhea in Adults and Children: A Global Perspective. Available online: https://www.worldgastroenterology.org/UserFiles/file/guidelines/acute-diarrhea-english-2012.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Nataro, J.P.; Guerrant, R.L. Chronic consequences on human health induced by microbial pathogens: Growth faltering among children in developing countries. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6807–6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sack, D.A. Recent progress in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vaccine research and development. Infect. Immun. 2025, e0036825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Duan, Q.; Zhang, W. Vaccines against gastroenteritis, current progress and challenges. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 1486–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sack, D.A. Progress and hurdles in the development of vaccines against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in humans. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2012, 11, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribble, D.R. Resistant pathogens as causes of traveller’s diarrhea globally and impact(s) on treatment failure and recommendations. J. Travel Med. 2017, 24, S6–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaveri, T.; Vilkman, K.; Pakkanen, S.; Kirveskari, J.; Kantele, A. Despite antibiotic treatment of travellers’ diarrhoea, pathogens are found in stools from half of travellers at return. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 23, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, R.M.; Schuetz, A.N. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Bacteria That Cause Gastroenteritis. Clin. Lab. Med. 2015, 35, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang-Latimer, J.; Jafri, S.; VanTassel, A.; Jiang, Z.D.; Gurleen, K.; Rodriguez, S.; Nandy, R.K.; Ramamurthy, T.; Chatterjee, S.; McKenzie, R.; et al. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial enteropathogens isolated from international travelers to Mexico, Guatemala, and India from 2006 to 2008. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomi, H.; Jiang, Z.D.; Adachi, J.A.; Ashley, D.; Lowe, B.; Verenkar, M.P.; Steffen, R.; Dupont, H.L. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacterial enteropathogens causing traveler’s diarrhea in four geographic regions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennerholm, A.M.; Holmgre, J. Oral B-subunit whole-cell vaccines against cholera and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhoea. In Molecular and Clinical Aspects of Bacterial Vaccine Development; Ala’Aldeen, D., Hormaeche, C.E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1995; pp. 205–232. [Google Scholar]

- Qadri, F.; Saha, A.; Ahmed, T.; Al Tarique, A.; Begum, Y.A.; Svennerholm, A.-M. Disease burden due to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in the first 2 years of life in an urban community in Bangladesh. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 3961–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, K.; Antikainen, J.; Laaveri, T.; Kirveskari, J.; Svennerholm, A.M.; Kantele, A. Clinical aspects of heat-labile and heat-stable toxin-producing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: A prospective study among Finnish travellers. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 38, 101855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; Francis, D.H.; Fang, Y.; Knudsen, D.; Nataro, J.P.; Robertson, D.C. Genetic fusions of heat-labile (LT) and heat-stable (ST) toxoids of porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli elicit neutralizing anti-LT and anti-STa antibodies. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ruan, X.; Zhang, C.; Lawson, S.R.; Knudsen, D.E.; Nataro, J.P.; Robertson, D.C.; Zhang, W. Heat-labile- and heat-stable-toxoid fusions (LTR192G-STaP13F of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli elicit neutralizing antitoxin antibodies. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 4002–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxt, A.M.; Diaz, Y.; Bacle, A.; Grauffel, C.; Reuter, N.; Aasland, R.; Sommerfelt, H.; Puntervoll, P. Characterization of immunological cross-reactivity between enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli heat-stable toxin and human guanylin and uroguanylin. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 2913–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Zhang, W. Development of effective vaccines for enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolick, D.T.; Medeiros, P.; Ledwaba, S.E.; Lima, A.A.M.; Nataro, J.P.; Barry, E.M.; Guerrant, R.L. Critical Role of Zinc in a New Murine Model of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Diarrhea. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spira, W.M.; Sack, R.B.; Froehlich, J.L. Simple adult rabbit model for Vibrio cholerae and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhea. Infect. Immun. 1981, 32, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennerholm, A.M.; Wenneras, C.; Holmgren, J.; McConnell, M.M.; Rowe, B. Roles of different coli surface antigens of colonization factor antigen II in colonization by and protective immunogenicity of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in rabbits. Infect. Immun. 1990, 58, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.W.; Linggood, M.A. Observations on the pathogenic properties of the K88, Hly and Ent plasmids of Escherichia coli with particular reference to porcine diarrhoea. J. Med. Microbiol. 1971, 4, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Rausch, D.; Zhang, W. Little heterogeneity among genes encoding heat-labile and heat-stable toxins of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from diarrheal pigs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 6402–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, F.R.; Hall, E.R.; Tribble, D.; Savarino, S.J.; Cassels, F.J.; Porter, C.; Meza, R.; Nunez, G.; Espinoza, N.; Salazar, M.; et al. The New World primate, Aotus nancymae, as a model for examining the immunogenicity of a prototype enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli subunit vaccine. Vaccine 2006, 24, 3786–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, A.; Joseph, S.S.; Reynolds, N.D.; Poncet, D.; Maciel, M., Jr.; Nunez, G.; Espinoza, N.; Nieto, M.; Castillo, R.; Royal, J.M.; et al. Evaluation of the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a recombinant CS6-based ETEC vaccine in an Aotus nancymaae CS6 + ETEC challenge model. Vaccine 2021, 39, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.; Robertson, D.C.; Nataro, J.P.; Clements, J.D.; Zhang, W.; STa Toxoid Vaccine Consortium Group. Characterization of heat-stable (STa) toxoids of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli fused to a double mutant heat-labile toxin (dmLT) peptide in inducing neutralizing anti-STa antibodies. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 1823–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxt, A.M.; Diaz, Y.; Aasland, R.; Clements, J.D.; Nataro, J.P.; Sommerfelt, H.; Puntervoll, P. Towards Rational Design of a Toxoid Vaccine against the Heat-Stable Toxin of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Lu, T.; Nandre, R.M.; Duan, Q.; Zhang, W. Immunogenicity characterization of genetically fused or chemically conjugated heat-stable toxin toxoids of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in mice and pigs. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2019, 366, fnz037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennerholm, A.M.; Holmgren, J.; Sack, D.A. Development of oral vaccines against enterotoxinogenic Escherichia coli diarrhoea. Vaccine 1989, 7, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, F.M.; Laine, R.O.; Afrin, S.; Nakajima, R.; Akhtar, M.; Vickers, T.; Parker, K.; Nizam, N.N.; Grigura, V.; Goss, C.W.; et al. Contribution of Noncanonical Antigens to Virulence and Adaptive Immunity in Human Infection with Enterotoxigenic E. coli. Infect. Immun. 2021, 89, e00041-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidean, S.D.; Riddle, M.S.; Savarino, S.J.; Porter, C.K. A systematic review of ETEC epidemiology focusing on colonization factor and toxin expression. Vaccine 2011, 29, 6167–6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mentzer, A.; Connor, T.R.; Wieler, L.H.; Semmler, T.; Iguchi, A.; Thomson, N.R.; Rasko, D.A.; Joffre, E.; Corander, J.; Pickard, D.; et al. Identification of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) clades with long-term global distribution. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, F.M.; Martin, J.; Hazen, T.H.; Vickers, T.J.; Pashos, M.; Okhuysen, P.C.; Gomez-Duarte, O.G.; Cebelinski, E.; Boxrud, D.; Del Canto, F.; et al. Conservation and global distribution of non-canonical antigens in Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, A.; Bourgeois, L.; Carlin, N.; Clements, J.; Gustafsson, B.; Hartford, M.; Holmgren, J.; Petzold, M.; Walker, R.; Svennerholm, A.M. Safety and immunogenicity of an improved oral inactivated multivalent enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) vaccine administered alone and together with dmLT adjuvant in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase I study. Vaccine 2014, 32, 7077–7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.K.; Stephens, J.C.; Beavis, J.C.; Greenwood, J.; Gewert, C.; Randall, R.; Freeman, D.; Darsley, M.J. Generation and Characterization of a Live Attenuated Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Combination Vaccine Expressing Six Colonization Factors and Heat-Labile Toxin Subunit B. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18, 2128–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.; Knudsen, D.E.; Wollenberg, K.M.; Sack, D.A.; Zhang, W. Multiepitope fusion antigen induces broadly protective antibodies that prevent adherence of Escherichia coli strains expressing colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I), CFA/II, and CFA/IV. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2014, 21, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lee, K.H.; Zhang, W. Multiepitope fusion antigen: MEFA, an epitope- and structure-based vaccinology platform for multivalent vaccine development. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Bidmos, F., Bosse, J., Langford, P., Eds.; Bacterial Vaccines; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 2414, pp. 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Moxley, R.A.; Zhang, W. Mapping the neutralizing epitopes of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) K88 (F4) fimbrial adhesin and major subunit FaeG. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e00329-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Seo, H.; Moxley, R.A.; Zhang, W. Mapping the neutralizing epitopes of F18 fimbrial adhesin subunit FedF of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 230, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, X.; Upadhyay, I.; Zhang, W. Characterization of Functional B-Cell Epitopes at the Amino Terminus of Shigella Invasion Plasmid Antigen B (IpaB). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0038422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, W. Mapping the functional B-cell epitopes of Shigella invasion plasmid antigen D (IpaD). Appl Environ Microbiol 2024, 90, e0098824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhwal, A.; Vakamalla, S.S.R.; Li, S.; Zhang, W. Characterization of Shigella virulence factor intracellular spread A (IcsA, or VirG) functional epitopes against S. flexneri 2a and S. sonnei invasion and adherence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e0117525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Seo, H.; Upadhyay, I.; Zhang, W. A Polyvalent Adhesin-Toxoid Multiepitope-Fusion-Antigen-Induced Functional Antibodies against Five Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Adhesins (CS7, CS12, CS14, CS17, and CS21) but Not Enterotoxins (LT and STa). Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Lee, K.H.; Nandre, R.M.; Garcia, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W. MEFA (multiepitope fusion antigen)-novel technology for structural vaccinology, proof from computational and empirical immunogenicity characterization of an enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) adhesin MEFA. J. Vaccines Vaccin 2017, 8, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Lu, T.; Garcia, C.; Yanez, C.; Nandre, R.M.; Sack, D.A.; Zhang, W. Co-administered tag-less toxoid fusion 3xSTaN12S-mnLTR192G/L211A and CFA/I/II/IV MEFA (multiepitope fusion antigen) induce neutralizing antibodies to 7 adhesins (CFA/I, CS1-CS6) and both enterotoxins (LT, STa) of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, e1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Nandre, R.M.; Nietfeld, J.; Chen, Z.; Duan, Q.; Zhang, W. Antibodies induced by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) adhesin major structural subunit and minor tip adhesin subunit equivalently inhibit bacteria adherence in vitro. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.M., Jr.; Seo, H.; Zhang, W.; Sack, D.A. A multi-epitope fusion antigen candidate vaccine for Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is protective against strain B7A colonization in a rabbit model. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Berberov, E.M.; Freeling, J.; He, D.; Moxley, R.A.; Francis, D.H. Significance of heat-stable and heat-labile enterotoxins in porcine colibacillosis in an additive model for pathogenicity studies. Infect. Immun 2006, 74, 3107–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennerholm, A.M.; Lindblad, M.; Svennerholm, B.; Holmgren, J. Synthesis of Nontoxic, Antibody-Binding Escherichia-Coli Heat-Stable Entero-Toxin (Sta) Peptides. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1988, 55, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, S.I.H.; Hirayama, T.; Takeda, Y.; Shimonishi, Y. Effects on the activity of amino acids replacement at positions 12, 13, and 14 heat-stable enterotoxin (STh) by chemical synthesis. In Proceedings of the 24th Joint Conf. U.S.-Japan Cooperative Med. Sci. Program on Cholera and Related Diarrheal Disease Panel, Tokyo, Japan, 13–16 November 1988; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, J.D. Construction of a nontoxic fusion peptide for immunization against Escherichia coli strains that produce heat-labile and heat-stable enterotoxins. Infect. Immun. 1990, 58, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, J.; Svennerholm, A.M.; Holmgren, J. Genetic fusion of a non-toxic heat-stable enterotoxin-related decapeptide antigen to cholera toxin B-subunit. FEBS Lett. 1988, 241, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.; Uhlin, B.E.; Grundstrom, T.; Holmgren, J.; Hirst, T.R. Immunoactive chimeric ST-LT enterotoxins of Escherichia coli generated by in vitro gene fusion. FEBS Lett. 1986, 208, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennerholm, A.M.; Holmgren, J. Oral vaccines against cholera and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhea. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1995, 371B, 1623–1628. [Google Scholar]

- Batisson, I.; Der Vartanian, M. Contribution of defined amino acid residues to the immunogenicity of recombinant Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin fusion proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 192, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, W. Escherichia coli K88ac fimbriae expressing heat-labile and heat-stable (STa) toxin epitopes elicit antibodies that neutralize cholera toxin and STa toxin and inhibit adherence of K88ac fimbrial E. coli. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010, 17, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Knudsen, D.E.; Liu, M.; Robertson, D.C.; Zhang, W.; STa Toxoid Vacine Consortium Group. Toxicity and immunogenicity of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli heat-labile and heat-stable toxoid fusion 3xSTaA14Q-LTS63K/R192G/L211A in a murine model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandre, R.; Ruan, X.; Duan, Q.; Zhang, W. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli heat-stable toxin and heat-labile toxin toxoid fusion 3xSTaN12S-dmLT induces neutralizing anti-STa antibodies in subcutaneously immunized mice. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, fnw246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandre, R.M.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. Passive antibodies derived from intramuscularly immunized toxoid fusion 3xSTaN12S-dmLT protect against STa+ enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) diarrhea in a pig model. Vaccine 2017, 35, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Huang, J.; Xiao, N.; Seo, H.; Zhang, W. Neutralizing anti-STa antibodies derived from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) toxoid fusions with heat-stable toxin (STa) mutant STaN12S, STaL9A/N12S or STaN12S/A14T show little cross-reactivity with guanylin or uroguanylin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 84, e01737-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Garcia, C.; Ruan, X.; Duan, Q.; Sack, D.A.; Zhang, W. Preclinical characterization of immunogenicity and efficacy against diarrhea from MecVax, a multivalent enterotoxigenic E. coli vaccine candidate. Infect. Immun. 2021, 89, e0010621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.Y.; Seo, H.; Sack, D.A.; Zhang, W. Intradermally Administered Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Vaccine Candidate MecVax Induces Functional Serum Immunoglobulin G Antibodies against Seven Adhesins (CFA/I and CS1 through CS6) and Both Toxins (STa and LT). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0213921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Duan, Q.; Upadhyay, I.; Zhang, W. Evaluation of Multivalent Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Vaccine Candidate MecVax Antigen Dose-Dependent Effect in a Murine Model. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0095922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, I.; Lauder, K.L.; Li, S.; Ptacek, G.; Zhang, W. Intramuscularly Administered Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) Vaccine Candidate MecVax Prevented H10407 Intestinal Colonization in an Adult Rabbit Colonization Model. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0147322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, I.; Parvej, S.M.D.; Shen, Y.; Li, S.; Lauder, K.L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W. Protein-based vaccine candidate MecVax broadly protects against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli intestinal colonization in a rabbit model. Infect. Immun. 2023, 91, e0027223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edao, B.; Upadhyay, I.; Zhang, W. Effect of 5% lactose and 0.1% polysorbate 80 buffer on protein-based multivalent ETEC vaccine candidate MecVax stabilization and immunogenicity. Vaccine 2025, 63, 127634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, I.; Edao, B.; Zhang, W. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Vaccine Candidate MecVax With Protein Antigens Prepared From Animal-Free Media Is Equally Immunogenic and Protective Against Adhesins CFA/I, CS1-CS6 and Toxins LT and STa. Microbiol. Immunol. 2025, 69, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, I.; Li, S.; Ptacek, G.; Seo, H.; Sack, D.A.; Zhang, W. A polyvalent multiepitope protein cross-protects against Vibrio cholerae infection in rabbit colonization and passive protection models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2202938119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, I.; Parvej, S.M.D.; Li, S.; Lauder, K.L.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, W. Polyvalent Protein Adhesin MEFA-II Induces Functional Antibodies against Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) Adhesins CS7, CS12, CS14, CS17, and CS21 and Heat-Stable Toxin (STa). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0068323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Li, S.Q.; Upadhyay, I.; Lauder, K.L.; Sack, D.A.; Zhang, W.P. MecVax supplemented with CFA MEFA-II induces functional antibodies against 12 adhesins (CFA/I, CS1-CS7, CS12, CS14, CS17, and CS21) and 2 toxins (STa, LT) of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0415323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Anvari, S.; Ptacek, G.; Upadhyay, I.; Kaminski, R.W.; Sack, D.A.; Zhang, W. A broadly immunogenic polyvalent Shigella multiepitope fusion antigen protein protects against Shigella sonnei and Shigella flexneri lethal pulmonary challenges in mice. Infect. Immun. 2023, 91, e0031623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Upadhyay, I.; Seo, H.; Vakamalla, S.S.R.; Madhwal, A.; Sack, D.A.; Zhang, W. Immunogenicity and preclinical efficacy characterization of ShecVax, a combined vaccine against Shigella and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 2025, 93, e0000425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M.; Kaminski, R.W.; Lugo-Roman, L.A.; Carrillo, H.G.; Tilley, D.H.; Baldeviano, C.; Simons, M.P.; Reynolds, N.D.; Ranallo, R.T.; Suvarnapunya, A.E.; et al. Development of an Aotus nancymaae Model for Shigella Vaccine Immunogenicity and Efficacy Studies. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 2027–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cray, W.C., Jr.; Tokunaga, E.; Pierce, N.F. Successful colonization and immunization of adult rabbits by oral inoculation with Vibrio cholerae O1. Infect. Immun. 1983, 41, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Robertson, D.C.; Zhang, C.; Bai, W.; Zhao, M.; Francis, D.H. Escherichia coli constructs expressing human or porcine enterotoxins induce identical diarrheal diseases in a piglet infection model. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 5832–5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandre, R.; Ruan, X.; Lu, T.; Duan, Q.; Sack, D.; Zhang, W. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli adhesin-toxoid multiepitope fusion antigen CFA/I/II/IV-3xSTaN12S-mnLTR192G/L211A-derived antibodies inhibit adherence of seven adhesins, neutralize enterotoxicity of LT and STa toxins, and protect piglets against diarrhea. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00550-00517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Sack, D.A. Current Progress in Developing Subunit Vaccines against Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-Associated Diarrhea. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2015, 22, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, W. MecVax, an Epitope- and Structure-Based Broadly Protective Subunit Vaccine Against Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2866. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122866

Zhang W. MecVax, an Epitope- and Structure-Based Broadly Protective Subunit Vaccine Against Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2866. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122866

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Weiping. 2025. "MecVax, an Epitope- and Structure-Based Broadly Protective Subunit Vaccine Against Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC)" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2866. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122866

APA StyleZhang, W. (2025). MecVax, an Epitope- and Structure-Based Broadly Protective Subunit Vaccine Against Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Microorganisms, 13(12), 2866. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122866