Evaluating Associations Between Drought and West Nile Virus Epidemics: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of Relevant Search Terms and Databases

2.2. Screening and Data Extraction

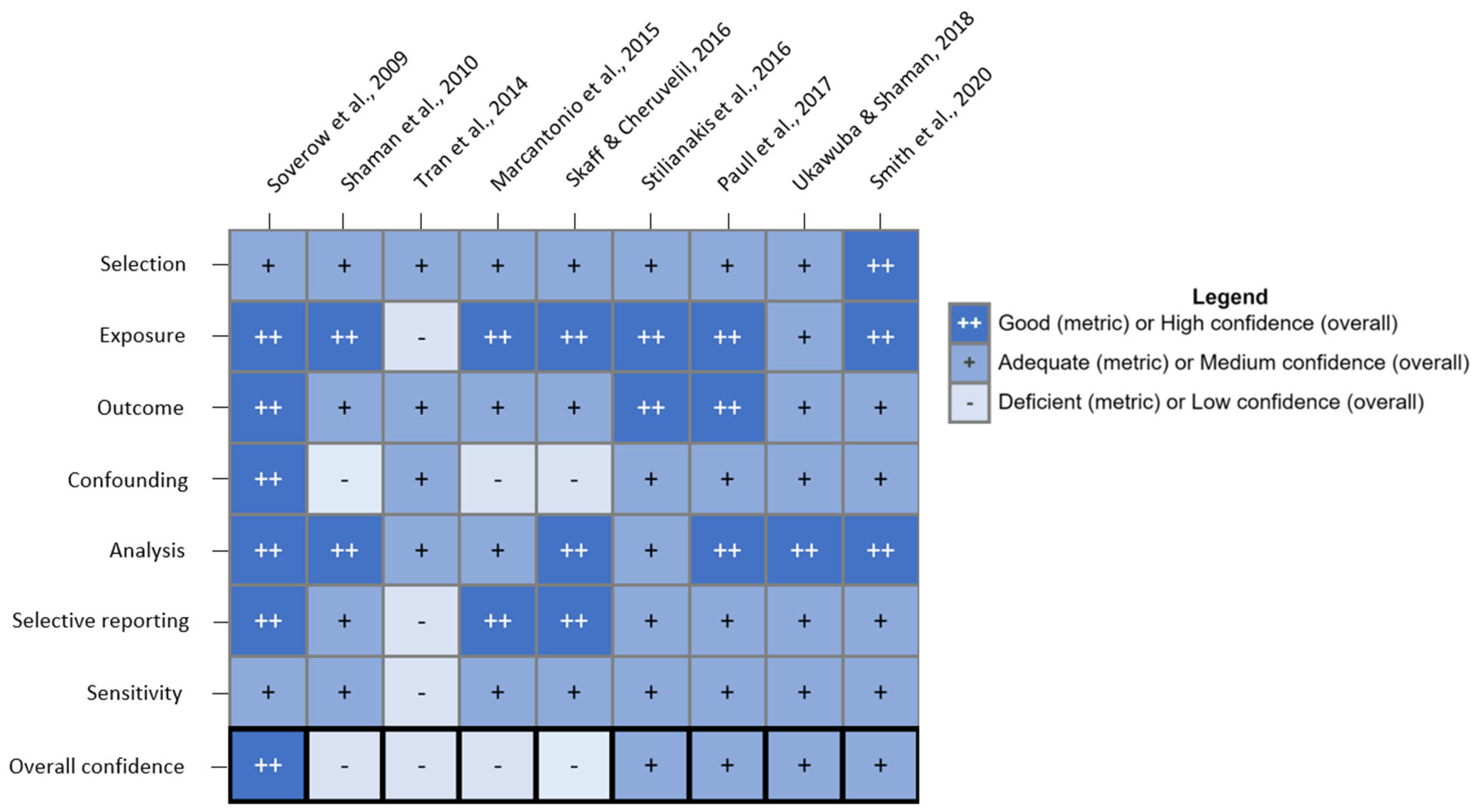

2.3. Study Quality Evaluation

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MNDWI | Modified Normalized Difference Water Index |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index |

| RZSM | root zone soil moisture |

| WNF | West Nile fever |

| WNND | West Nile neuroinvasive disease |

| WNV | West Nile Virus |

References

- DeBiasi, R.L.; Tyler, K.L. West Nile Virus Meningoencephalitis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2006, 2, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). West Nile Virus: Clinical Signs and Symptoms; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Denman, S.; Hart, A.M. Arthropod-Borne Disease: West Nile Fever. J. Nurse Pract. 2015, 11, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, N.P.; Fischer, M.; Neitzel, D.; Schiffman, E.; Salas, M.L.; Glaser, C.A.; Sylvester, T.; Kretschmer, M.; Bunko, A.; Staples, J.E. Hospital-Based Enhanced Surveillance for West Nile Virus Neuroinvasive Disease. Epidemiol. Infect. 2016, 144, 3170–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, P.R.; Defilippo, C. West Nile Virus and Drought. Glob. Change Hum. Health 2001, 2, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaman, J.; Day, J.F.; Stieglitz, M. Drought-Induced Amplification and Epidemic Transmission of West Nile Virus in Southern Florida. J. Med. Entomol. 2005, 42, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcantonio, M.; Rizzoli, A.; Metz, M.; Rosà, R.; Marini, G.; Chadwick, E.; Neteler, M. Identifying the Environmental Conditions Favouring West Nile Virus Outbreaks in Europe. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, S.H.; Horton, D.E.; Ashfaq, M.; Rastogi, D.; Kramer, L.D.; Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Kilpatrick, A.M. Drought and Immunity Determine the Intensity of West Nile Virus Epidemics and Climate Change Impacts. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 284, 20162078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Poloczanska, E.S.; Mintenbeck, K.; Tignor, M.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; et al. Summary for Policymakers. In IPCC 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 3–33. ISBN 978-1-00-932584-4. [Google Scholar]

- Payton, E.A.; Pinson, A.O.; Asefa, T.; Condon, L.E.; Dupigny-Girouz, L.-A.; Harding, B.L.; Kiang, J.; Lee, D.H.; McAfee, S.A.; Pflug, J.M.; et al. Water. In Fifth National Climate Assessment; Crimmins, A.R., Avery, C.W., Easterling, D.R., Kunkel, K.E., Stewart, B.C., Maycock, T.K., Eds.; U.S. Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). West Nile Virus: Historic Data 1999–2023; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmer, M. Unprecedented Outbreak of West Nile Virus—Maricopa County, Arizona, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizona Drought Monitoring Committee. Drought Status Report, September 2021. Available online: https://www.azwater.gov/sites/default/files/2023-09/Sep%2721_S%26LDroughtReport_Final.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Brown, J.J.; Pascual, M.; Wimberly, M.C.; Johnson, L.R.; Murdock, C.C. Humidity—The Overlooked Variable in the Thermal Biology of Mosquito-Borne Disease. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 1029–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett-Jones, C. Prognosis for Interruption of Malaria Transmission Through Assessment of the Mosquito’s Vectorial Capacity. Nature 1964, 204, 1173–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadis, T.G. The Contribution of Culex pipiens Complex Mosquitoes to Transmission and Persistence of West Nile Virus in North America. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2012, 28, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, D.M.; Keyghobadi, N.; Malcolm, C.A.; Mehmet, C.; Schaffner, F.; Mogi, M.; Fleischer, R.C.; Wilkerson, R.C. Emerging Vectors in the Culex pipiens Complex. Science 2004, 303, 1535–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamer, G.L.; Kitron, U.D.; Brawn, J.D.; Loss, S.R.; Ruiz, M.O.; Goldberg, T.L.; Walker, E.D. Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae): A Bridge Vector of West Nile Virus to Humans. J. Med. Entomol. 2008, 45, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCarlo, C.H.; Campbell, S.R.; Bigler, L.L.; Mohammed, H.O. Aedes japonicus and West Nile Virus in New York. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2020, 36, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, R.E.; Feiszli, T.; Foss, L.; Messenger, S.; Fang, Y.; Barker, C.M.; Reisen, W.K.; Vugia, D.J.; Padgett, K.A.; Kramer, V.L. West Nile Virus in California, 2003–2018: A Persistent Threat. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.F. Mosquito Oviposition Behavior and Vector Control. Insects 2016, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonesh, J.R.; Blaustein, L. Predator-Induced Shifts in Mosquito Oviposition Site Selection: A Meta-Analysis and Implications for Vector Control. Isr. J. Ecol. Evol. 2010, 56, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.C.; Herzog, C.M.; Gajewski, Z.; Ramsay, C.; El Moustaid, F.; Evans, M.V.; Desai, T.; Gottdenker, N.L.; Hermann, S.L.; Power, A.G.; et al. Both Consumptive and Non-Consumptive Effects of Predators Impact Mosquito Populations and Have Implications for Disease Transmission. eLife 2022, 11, e71503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smartt, C.T.; Richards, S.L.; Anderson, S.L.; Vitek, C.J. Effects of Forced Egg Retention on the Temporal Progression of West Nile Virus Infection in Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae). Environ. Entomol. 2010, 39, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, R.W.; Didion, E.M.; Rosselot, A.E.; Holmes, C.J.; Siler, S.C.; Rosendale, A.J.; Hendershot, J.M.; Elliot, K.S.B.; Jennings, E.C.; Nine, G.A.; et al. Dehydration Prompts Increased Activity and Blood Feeding by Mosquitoes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.R.; Furnas, B.J.; Calhoun, K.L.; Larsen, A.E.; Karp, D.S.; de Valpine, P. Drought Influences Habitat Associations and Abundances of Birds in California’s Central Valley. Divers. Distrib. 2024, 30, e13827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, L.; Barker, C.M.; Moore, C.G.; Pape, W.J.; Winters, A.M.; Cheronis, N. Irrigated Agriculture Is an Important Risk Factor for West Nile Virus Disease in the Hyperendemic Larimer-Boulder-Weld Area of North Central Colorado. J. Med. Entomol. 2010, 47, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepczyk, C.A.; Mertig, A.G.; Liu, J. Assessing Landowner Activities Related to Birds Across Rural-to-Urban Landscapes. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deichmeister, J.M.; Telang, A. Abundance of West Nile Virus Mosquito Vectors in Relation to Climate and Landscape Variables. J. Vector Ecol. 2011, 36, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, J.D.; Abadi, A.M.; Bell, J.E. Existing Challenges and Opportunities for Advancing Drought and Health Research. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.; Andersen, D.; Jaramillo, S.; Hojnacki, J.; Riehle, M.; Rappazzo, K.; Ernst, K.; Hilborn, E.; Deflorio-Barker, S.; Combrink, L. Evaluating the Evidence of an Association between Drought and West Nile Virus Epidemics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PROSPERO 2024 CRD42024503289. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024503289 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Howard, B.E.; Phillips, J.; Tandon, A.; Maharana, A.; Elmore, R.; Mav, D.; Sedykh, A.; Thayer, K.; Merrick, B.A.; Walker, V.; et al. SWIFT-Active Screener: Accelerated Document Screening through Active Learning and Integrated Recall Estimation. Environ. Int. 2020, 138, 105623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimberly, M.C.; Lamsal, A.; Giacomo, P.; Chuang, T.-W. Regional Variation of Climatic Influences on West Nile Virus Outbreaks in the United States. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 91, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, A.A.; Boyles, A.L.; Wolfe, M.S.; Bucher, J.R.; Thayer, K.A. Systematic Review and Evidence Integration for Literature-Based Environmental Health Science Assessments. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). ORD Staff Handbook for Developing IRIS Assessments; EPA 600/R-22/268; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Health Assessment Workspace Collaborative (HAWC). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/risk/health-assessment-workspace-collaborative-hawc (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Shaman, J.; Day, J.; Komar, N. Hydrologic Conditions Describe West Nile Virus Risk in Colorado. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaff, N.K.; Cheruvelil, K.S. Fine-Scale Wetland Features Mediate Vector and Climate-Dependent Macroscale Patterns in Human West Nile Virus Incidence. Landsc. Ecol. 2016, 31, 1615–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.H.; Tyre, A.J.; Hamik, J.; Hayes, M.J.; Zhou, Y.; Dai, L. Using Climate to Explain and Predict West Nile Virus Risk in Nebraska. GeoHealth 2020, 4, e2020GH000244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soverow, J.E.; Wellenius, G.A.; Fisman, D.N.; Mittleman, M.A. Infectious Disease in a Warming World: How Weather Influenced West Nile Virus in the United States (2001–2005). Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukawuba, I.; Shaman, J. Association of Spring-Summer Hydrology and Meteorology with Human West Nile Virus Infection in West Texas, USA, 2002–2016. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stilianakis, N.I.; Syrris, V.; Petroliagkis, T.; Pärt, P.; Gewehr, S.; Kalaitzopoulou, S.; Mourelatos, S.; Baka, A.; Pervanidou, D.; Vontas, J.; et al. Identification of Climatic Factors Affecting the Epidemiology of Human West Nile Virus Infections in Northern Greece. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.; Sudre, B.; Paz, S.; Rossi, M.; Desbrosse, A.; Chevalier, V.; Semenza, J.C. Environmental Predictors of West Nile Fever Risk in Europe. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambri, V.; Capobianchi, M.; Charrel, R.; Fyodorova, M.; Gaibani, P.; Gould, E.; Niedrig, M.; Papa, A.; Pierro, A.; Rossini, G.; et al. West Nile Virus in Europe: Emergence, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dracup, J.A.; Lee, K.S.; Paulson, E.G., Jr. On the Definition of Droughts. Water Resour. Res. 1980, 16, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroote, J.; Sugumaran, R.; Ecker, M. Landscape, Demographic and Climatic Associations with Human West Nile Virus Occurrence Regionally in 2012 in the United States of America. Geospat. Health 2014, 9, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaman, J.; Harding, K.; Campbell, S.R. Meteorological and Hydrological Influences on the Spatial and Temporal Prevalence of West Nile Virus in Culex Mosquitoes, Suffolk County, New York. J. Med. Entomol. 2011, 48, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, N.S. The 2011–2012 Drought in the United States: New Lessons from a Record Event. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2014, 30, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisen, W.K.; Fang, Y.; Martinez, V.M. Effects of Temperature on the Transmission of West Nile Virus by Culex tarsalis (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2006, 43, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclure, M.; Mittleman, M.A. Should We Use a Case-Crossover Design? Annu. Rev. Public Health 2000, 21, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harp, R.D.; Holcomb, K.M.; Benjamin, S.G.; Green, B.W.; Jones, H.; Johansson, M.A. A Regionally Determined Climate-Informed West Nile Virus Forecast Technique. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author & Year | Title | Location & Time Period | Lag Between Drought & WNV Cases | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soverow et al., 2009 [40] | Infectious Disease in a Warming World: How Weather Influenced West Nile Virus in the United States (2001–2005) | 17 states across the US (county-level data); 2001–2005 | Investigates whether drought conditions influence human WNV cases during the same year. | Mean weekly humidity was associated with higher incidence of human WNV cases over the subsequent three weeks. |

| Shaman et al., 2010 [37] | Hydrologic Conditions Describe West Nile Virus Risk in Colorado | Colorado, US (county-level data); 2002–2007 | Investigates whether drought conditions influence human WNV cases during the same year. | In eastern CO, wet spring conditions, followed by dry summer conditions, were associated with human WNV cases. |

| Tran et al., 2014 [43] | Environmental Predictors of West Nile Fever Risk in Europe | Europe and its neighboring countries; 2002–2013 | Investigates whether drought conditions influence human WNV cases during the same year. | Above average surface water during an 8-day period in June was associated with higher numbers of West Nile outbreaks. |

| Marcantonio et al., 2015 [7] | Identifying the Environmental Conditions Favouring West Nile Virus Outbreaks in Europe | 16 countries across western Asia, Europe, and northern Africa; 2010–2012 | Investigates whether drought conditions influence human WNV cases during the same year. | Average Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) over a 4-month period from April to July was inversely associated with WNF outbreaks. |

| Skaff and Cheruvelil, 2016 [38] | Fine-scale Wetland Features Mediate Vector and Climate-dependent Macroscale Patterns in Human West Nile Virus Incidence | 17 states in the midwestern and northeastern US (county-level data); 2002–2012 | Investigates whether interannual variations in drought conditions influence human WNV cases during the second or third year. | Cx. tarsalis counties with a high proportional area of semi-permanent wetland that experienced non-drought to drought conditions had a higher incidence of human WNV cases than similar counties that experienced non-drought to non-drought, drought to drought, or drought to non-drought. |

| Stilianakis et al., 2016 [42] | Identification of Climatic Factors Affecting the Epidemiology of Human West Nile Virus Infections in Northern Greece | Northern Greece; 2010–2014 | Investigates whether drought conditions influence human WNV cases during the same year. | Weekly relative humidity and soil water content were both inversely associated with human WNV cases, with a lag time of up to 3 weeks. |

| Paull et al., 2017 [8] | Drought and Immunity Determine the Intensity of West Nile Virus Epidemics and Climate Change Impacts | Continental US (state-level data); 1999–2013 | Investigates whether drought conditions influence human WNND cases during the same year. | Drought measured over a 4-month period (May through August) was the primary climatic driver of increased WNV epidemics, rather than within-season or winter temperatures, or precipitation independently. |

| Ukawuba and Shaman, 2018 [41] | Association of Spring-summer Hydrology and Meteorology with Human West Nile Virus Infection in West Texas, USA, 2002–2016 | West Texas, US (county-level data); 2002–2016 | Investigates whether drought conditions influence human WNV cases during the same year | Wet conditions in the spring combined with dry and cool conditions in the summer are associated with increased annual WNV cases. |

| Smith et al., 2020 [39] | Using Climate to Explain and Predict West Nile Virus Risk in Nebraska | Nebraska, US (county-level data); 2002–2018 | Investigates whether variations in monthly drought conditions over a two-year period influence human WNV cases in the third year | A dry year preceded by a wet year was associated with higher incidence of human WNV cases in the following year. Drought accounted for 26% of WNV cases. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Russell, M.C.; Bliss, D.A.; Fischer, G.A.; Riehle, M.A.; Rappazzo, K.M.; Ernst, K.C.; Hilborn, E.D.; DeFlorio-Barker, S.; Combrink, L. Evaluating Associations Between Drought and West Nile Virus Epidemics: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122851

Russell MC, Bliss DA, Fischer GA, Riehle MA, Rappazzo KM, Ernst KC, Hilborn ED, DeFlorio-Barker S, Combrink L. Evaluating Associations Between Drought and West Nile Virus Epidemics: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122851

Chicago/Turabian StyleRussell, Marie C., Desiree A. Bliss, Gracie A. Fischer, Michael A. Riehle, Kristen M. Rappazzo, Kacey C. Ernst, Elizabeth D. Hilborn, Stephanie DeFlorio-Barker, and Leigh Combrink. 2025. "Evaluating Associations Between Drought and West Nile Virus Epidemics: A Systematic Review" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122851

APA StyleRussell, M. C., Bliss, D. A., Fischer, G. A., Riehle, M. A., Rappazzo, K. M., Ernst, K. C., Hilborn, E. D., DeFlorio-Barker, S., & Combrink, L. (2025). Evaluating Associations Between Drought and West Nile Virus Epidemics: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122851