Strain-Dependent Variability in Ochratoxin A Production by Aspergillus spp. Under Different In Vitro Cultivation Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains of the Genus Aspergillus

2.2. Cultivation Media and Conditions

2.3. Sample Preparation and HPLC Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Contribution of Factors Affecting OTA Productions

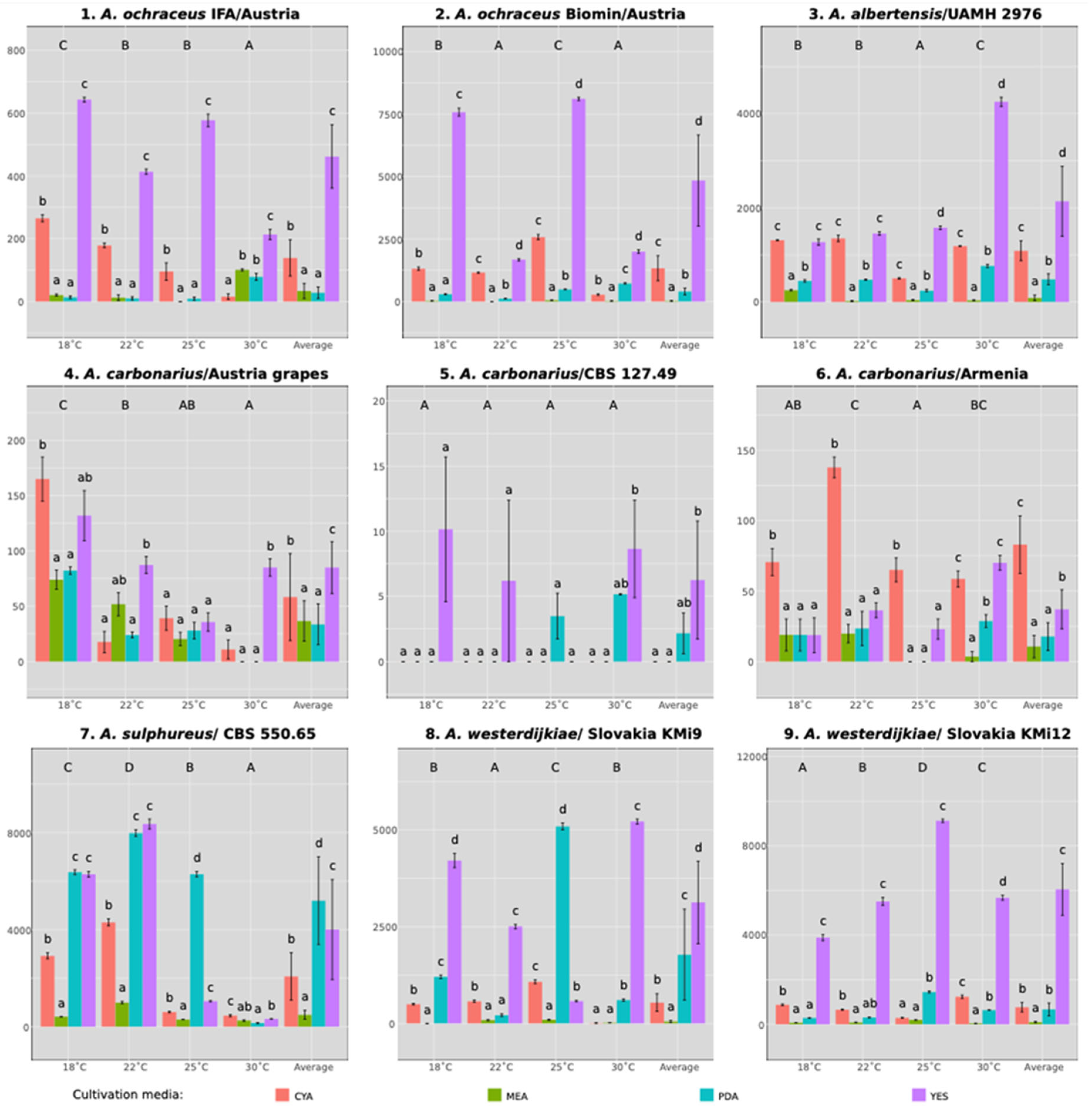

3.2. The Effect of Strain on OTA Production

3.3. The Effect of Media and Temperature on OTA Production

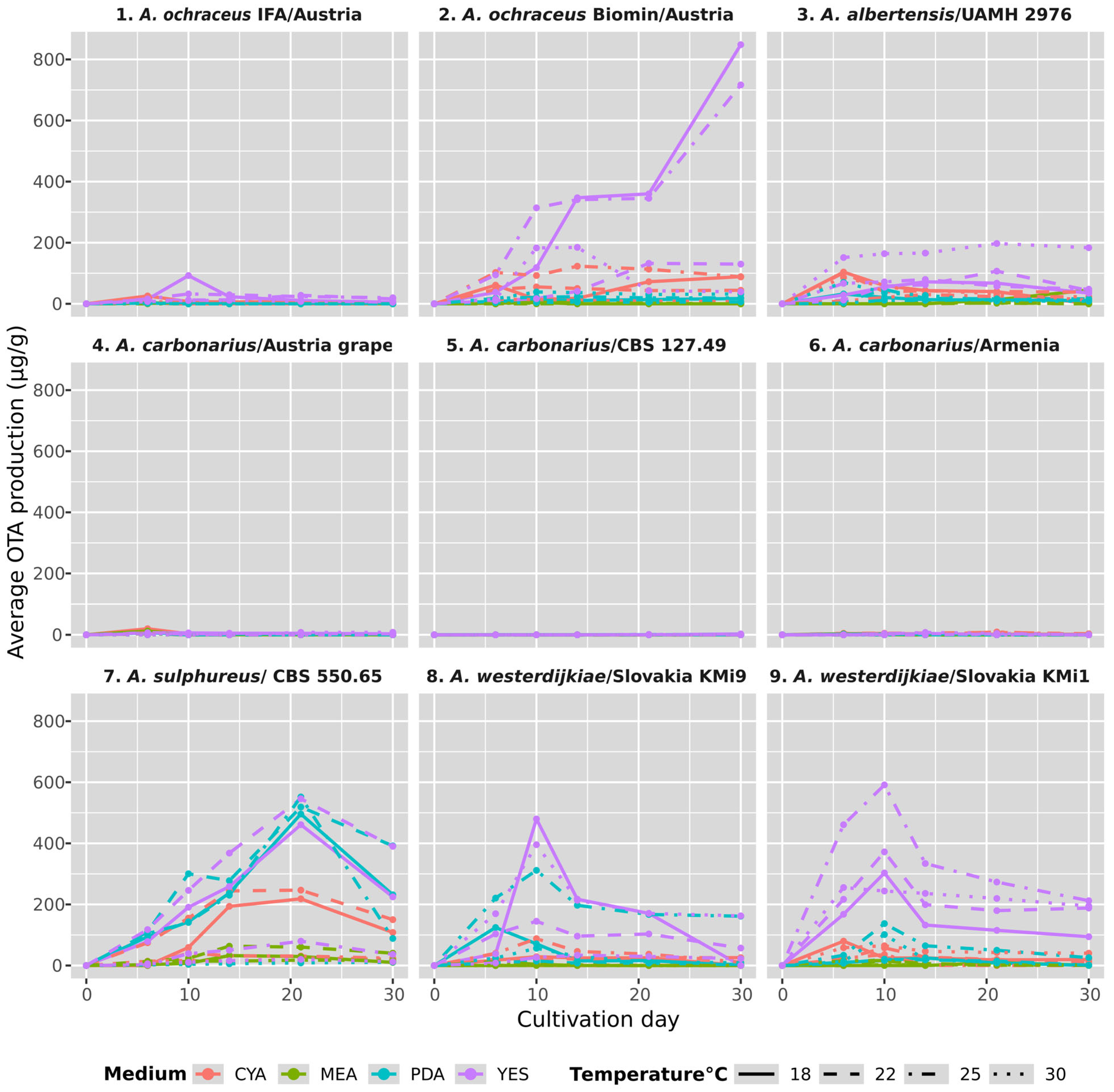

3.4. Temporal Variability in OTA Concentration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Esteban, A.; Abarca, M.L.; Bragulat, M.R.; Cabañes, F.J. Study of the Effect of Water Activity and Temperature on Ochratoxin A Production by Aspergillus carbonarius. Food Microbiol. 2006, 23, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimbalo, A.; Alonso-Garrido, M.; Font, G.; Manyes, L. Toxicity of Mycotoxins in Vivo on Vertebrate Organisms: A Review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 137, 111161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heussner, A.H.; Bingle, L.E.H. Comparative Ochratoxin Toxicity: A Review of the Available Data. Toxins 2015, 7, 4253–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Merwe, K.J.; Steyn, P.S.; Fourie, L.; Scott, D.B.; Theron, J.J. Ochratoxin A, a Toxic Metabolite Produced by Aspergillus ochraceus Wilh. Nature 1965, 205, 1112–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malir, F.; Ostry, V.; Pfohl-Leszkowicz, A.; Malir, J.; Toman, J. Ochratoxin A: 50 Years of Research. Toxins 2016, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khoury, A.; Atoui, A. Ochratoxin A: General Overview and Actual Molecular Status. Toxins 2010, 2, 461–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Anati, L.; Petzinger, E. Immunotoxic Activity of Ochratoxin A. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 29, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Hubka, V.; Ezekiel, C.N.; Hong, S.-B.; Nováková, A.; Chen, A.J.; Arzanlou, M.; Larsen, T.O.; Sklenář, F.; Mahakarnchanakul, W. Taxonomy of Aspergillus Section Flavi and Their Production of Aflatoxins, Ochratoxins and Other Mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 93, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostry, V.; Malir, F.; Ruprich, J. Producers and Important Dietary Sources of Ochratoxin A and Citrinin. Toxins 2013, 5, 1574–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amézqueta, S.; Schorr-Galindo, S.; Murillo-Arbizu, M.; González-Peñas, E.; López de Cerain, A.; Guiraud, J.P. OTA-Producing Fungi in Foodstuffs: A Review. Food Control 2012, 26, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.I. Biology and Ecology of Toxigenic Penicillium Species. In Mycotoxins and Food Safety; DeVries, J.W., Trucksess, M.W., Jackson, L.S., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 29–41. ISBN 978-1-4615-0629-4. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain Related to Ochratoxin A in Food. EFSA J. 2006, 4, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, E.; Heussner, A.H.; Dietrich, D.R. Species-, Sex-, and Cell Type-Specific Effects of Ochratoxin A and B. Toxicol. Sci. 2001, 63, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostry, V.; Malir, F.; Toman, J.; Grosse, Y. Mycotoxins as Human Carcinogens—The IARC Monographs Classification. Mycotoxin Res. 2017, 33, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Serna, J.; Vázquez, C.; García Sandino, F.; Márquez Valle, A.; González-Jaén, M.T.; Patiño, B. Evaluation of Growth and Ochratoxin A Production by Aspergillus steynii and Aspergillus westerdijkiae in Green-Coffee Based Medium under Different Environmental Conditions. Food Res. Int. 2014, 61, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, J.; Rigó, K.; Lamper, C.; Téren, J.; Szabó, G. Kinetics of Ochratoxin A Production in Different Aspergillus Species. Acta Biol. Hung. 2002, 53, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, L.; Guerreiro, T.M.; Pia, A.K.R.; Lima, E.O.; Oliveira, D.N.; Melo, C.F.O.R.; Catharino, R.R.; Sant’Ana, A.S. A Quantitative Study on Growth Variability and Production of Ochratoxin A and Its Derivatives by A. carbonarius and A. niger in Grape-Based Medium. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14573, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson, R.A.; Houbraken, J.; Thrane, U.; Frisvad, J.C.; Andersen, B. Food and Indoor Fungi; Westerdijk Laboratory Manual Series; Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 978-94-91751-18-9. [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Frank, J.M.; Houbraken, J.A.M.P.; Kuijpers, A.F.A.; Samson, R.A. New Ochratoxin A Producing Species of Aspergillus Section Circumdati. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 50, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, J.I.; Hocking, A.D. Fungi and Food Spoilage; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-92206-5. [Google Scholar]

- Visagie, C.M.; Varga, J.; Houbraken, J.; Meijer, M.; Kocsubé, S.; Yilmaz, N.; Fotedar, R.; Seifert, K.A.; Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Ochratoxin Production and Taxonomy of the Yellow Aspergilli (Aspergillus Section Circumdati). Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.I. The Genus Penicillium and Its Teleomorphic States Eupenicillium and Talaromyces; Academic Press: London, UK, 1979; ISBN 0-1255-7750-7. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, R.A.; Frisvad, J.C. Penicillium Subgenus Penicillium: New Taxonomic Schemes and Mycotoxins and Other Extrolites; Studies in mycology; CBS, Centralbureau voor Schimmelcultures: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; ISBN 978-90-70351-53-3. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, A.M.; de Vries, R.P.; Conesa, A.; de Bekker, C.; Talon, M.; Menke, H.H.; van Peij, N.N.M.E.; Wösten, H.A.B. Spatial Differentiation in the Vegetative Mycelium of Aspergillus niger. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 2311–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, A.; Abarca, M.L.; Bragulat, M.R.; Cabañes, F.J. Effects of Temperature and Incubation Time on Production of Ochratoxin A by Black Aspergilli. Res. Microbiol. 2004, 155, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarca, M.L.; Bragulat, M.R.; Castellá, G.; Cabañes, F.J. Impact of Some Environmental Factors on Growth and Ochratoxin A Production by Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus welwitschiae. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 291, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alborch, L.; Bragulat, M.R.; Abarca, M.L.; Cabañes, F.J. Effect of Water Activity, Temperature and Incubation Time on Growth and Ochratoxin A Production by Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus carbonarius on Maize Kernels. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 147, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, A.; Akbar, A.; Baazeem, A.; Rodriguez, A.; Magan, N. Climate change, food security and mycotoxins: Do we know enough? Fungal Biol. Rev. 2017, 31, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañes, F.J.; Bragulat, M.R. Black Aspergilli and Ochratoxin A-Producing Species in Foods. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, A.; Perrone, G.; Cozzi, G.; Solfrizzo, M. Managing Ochratoxin A Risk in the Grape-Wine Food Chain. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2008, 25, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragulat, M.R.; Abarca, M.L.; Castellá, G.; Cabañes, F.J. Intraspecific variability of growth and ochratoxin A production by Aspergillus carbonarius from different foods and geographical areas. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 306, 108273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susca, A.; Proctor, R.H.; Butchko, R.A.; Haidukowski, M.; Stea, G.; Logrieco, A.; Moretti, A. Variation in the fumonisin biosynthetic gene cluster in fumonisin-producing and nonproducing black Aspergilli. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014, 73, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnoli, C.; Violante, M.; Combina, M.; Palacio, G.; Dalcero, A. Mycoflora and ochratoxin-producing strains of Aspergillus section Nigri in wine grapes in Argentina. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 37, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadi, M.K.; Varveri, M.; Tsitsigiannis, D.I. Biological and Chemical Management of Aspergillus carbonarius and Ochratoxin A in Vineyards. Toxins 2024, 16, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayman, P.; Baker, J.L.; Doster, M.A.; Michailides, T.J.; Mahoney, N.E. Ochratoxin Production by the Aspergillus ochraceus Group and Aspergillus alliaceus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 2326–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, E.; Sanchis, V.; Ramos, A.J.; Marín, S. Non-Specificity of Nutritional Substrate for Ochratoxin A Production by Isolates of Aspergillus ochraceus. Food Microbiol. 2006, 23, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragulat, M.R.; Abarca, M.L.; Cabañes, F.J. An Easy Screening Method for Fungi Producing Ochratoxin A in Pure Culture. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 71, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciegler, A.; Fennell, D.J. Ochratoxin Synthesis by Penicillium Species. Naturwissenschaften 1972, 59, 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrinjar, M.; Dimić, G. Ochratoxigenicity of Aspergillus ochraceus Group and Penicillium verrucosum var. cyclopium Strains on Various Media. Acta Microbiol. Hung. 1992, 39, 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, F.; Frisvad, J.C. Penicillium verrucosum in Wheat and Barley Indicates Presence of Ochratoxin A. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filtenborg, O.; Frisvad, J.C.; Thrane, U. The Significance of Yeast Extract Composition on Metabolite Production in Penicillium. In Modern Concepts in Penicillium and Aspergillus Classification; Samson, R.A., Pitt, J.I., Eds.; NATO ASI Series; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 433–441. ISBN 978-1-4899-3579-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, H.; Neng, J.; Gao, J.; Yang, B.; Liu, Y. The Influence of NaCl and Glucose Content on Growth and Ochratoxin A Production by Aspergillus ochraceus, Aspergillus carbonarius and Penicillium nordicum. Toxins 2020, 12, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Lao, K.; Fan, F. Production, Toxicological Effects, and Control Technologies of Ochratoxin A Contamination: Addressing the Existing Challenges. Water 2024, 16, 3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meftah, S.; Abid, S.; Dias, T.; Rodrigues, P. Effect of Dry-Sausage Starter Culture and Endogenous Yeasts on Aspergillus westerdijkiae and Penicillium nordicum Growth and OTA Production. LWT 2018, 87, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandinidevi, S.; Jayapradha, C.; Balachandar, D.; Logrieco, A.F.; Velazhahan, R.; Paranidharan, V. Ochratoxin A and Aspergillus spp. Contamination in Brown and Polished Rice from Indian Markets. Toxins 2025, 17, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain No. | Identification/Section | Source/Origin | Strain No. | Identification/Section | Source/Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A. ochraceus */Circumdati | cereals/IFA/Austria | 6 | A. carbonarius */Nigri | grape berries/Armenia |

| 2 | A. ochraceus */Circumdati | cereals/Biomin/Austria | 7 | A. sulphureus 3/Circumdati CBS 550.68 | soil/India |

| 3 | A. albertensis 1/Flavi UAMH 2976 | ear swab/Canada | 8 | A. westerdijkiae 4/Circumdati KMi9 | grape berries/Slovakia |

| 4 | A. carbonarius */Nigri | grape berries/Austria | 9 | A. westerdijkiae 5/Circumdati KMi12 | grape berries/Slovakia |

| 5 | A. carbonarius 2/Nigri CBS 127.49 | coffee seeds/unknow |

| Strain No. | Identification | Conidiophore/ Ornamentation of Wall * | Conidial Color * | Conidial Shape/ Ornamentation * | Sclerotia/ Color * | Growth at 37 ± 1 °C ** | Growth on CREA/Acid Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A. ochraceus | biseriate/rough | ochre | globose/finally rough | +/white | yes | poor/no |

| 2 | A. ochraceus | biseriate/rough | ochre | globose/finally rough | +/white | yes | poor/no |

| 4 | A. carbonarius | biseriate/smooth | black | globose/rough | - | yes | poor/strong |

| 6 | A. carbonarius | biseriate/smooth | black | globose/rough | - | yes | poor/strong |

| Strain No. | Strain | Medium | t (°C) | n | AUTC | SD | Tukey HSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A. ochraceus IFA/Austria | YES | 25 | 3 | 577.21 | 34.75 | b |

| 2 | A. ochraceus Biomin/Austria | YES | 25 | 3 | 8113.56 | 113.62 | e |

| 3 | A. albertensis UAMH 2976 | YES | 30 | 3 | 4253.07 | 169.12 | c |

| 4 | A. carbonarius Austria, grapes | CYA | 18 | 3 | 165.02 | 34.56 | ba |

| 5 | A. carbonarius CBS 127.49 | YES | 18 | 3 | 10.14 | 9.62 | a |

| 6 | A. carbonarius Armenia | CYA | 22 | 3 | 137.75 | 12.92 | a |

| 7 | A. sulphureus CBS 550.65 | YES | 22 | 3 | 8348.9 | 357.84 | e |

| 8 | A. westerdijkiae Slovakia/KMi9 | YES | 30 | 3 | 5219.62 | 109.76 | d |

| 9 | A. westerdijkiae Slovakia/KMi12 | YES | 25 | 3 | 9123.15 | 131.3 | f |

| Strain No. | Strain | Medium | t (°C) | Max. Production OTA (μg g−1) | SD | Tukey HSD | Max. Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A. ochraceus IFA/Austria | YES | 18 | 92.36 | 06.60 | b | 10 |

| 2 | A. ochraceus Biomin/Austria | YES | 18 | 848.34 | 10.32 | f | 30 |

| 3 | A. albertensis UAMH 2976 | YES | 30 | 197.45 | 29.43 | c | 21 |

| 4 | A. carbonarius Austria, grapes | CYA | 18 | 19.90 | 02.23 | a | 6 |

| 5 | A. carbonarius CBS 127.49 | YES | 18 | 02.90 | 02.75 | a | 30 |

| 6 | A. carbonarius Armenia | CYA | 25 | 09.28 | 02.10 | a | 21 |

| 7 | A. sulphureus CBS 550.65 | PDA | 25 | 551.94 | 21.07 | e | 21 |

| 8 | A. westerdijkiae Slovakia/KMi9 | YES | 18 | 479.74 | 32.12 | d | 10 |

| 9 | A. westerdijkiae Slovakia/KMi12 | YES | 25 | 591.28 | 05.97 | e | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barboráková, Z.; Tančinová, D.; Medo, J.; Jakabová, S.; Häubl, G.; Jaunecker, G.; Mašková, Z.; Labuda, R. Strain-Dependent Variability in Ochratoxin A Production by Aspergillus spp. Under Different In Vitro Cultivation Conditions. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122850

Barboráková Z, Tančinová D, Medo J, Jakabová S, Häubl G, Jaunecker G, Mašková Z, Labuda R. Strain-Dependent Variability in Ochratoxin A Production by Aspergillus spp. Under Different In Vitro Cultivation Conditions. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122850

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarboráková, Zuzana, Dana Tančinová, Juraj Medo, Silvia Jakabová, Georg Häubl, Günther Jaunecker, Zuzana Mašková, and Roman Labuda. 2025. "Strain-Dependent Variability in Ochratoxin A Production by Aspergillus spp. Under Different In Vitro Cultivation Conditions" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122850

APA StyleBarboráková, Z., Tančinová, D., Medo, J., Jakabová, S., Häubl, G., Jaunecker, G., Mašková, Z., & Labuda, R. (2025). Strain-Dependent Variability in Ochratoxin A Production by Aspergillus spp. Under Different In Vitro Cultivation Conditions. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122850