Diversity of CRISPR-Cas Systems Identified in Urological Escherichia coli Strains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. DNA Isolation and PCR Amplification

2.3. Whole-Genome Sequencing

2.4. Genomic Analysis

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

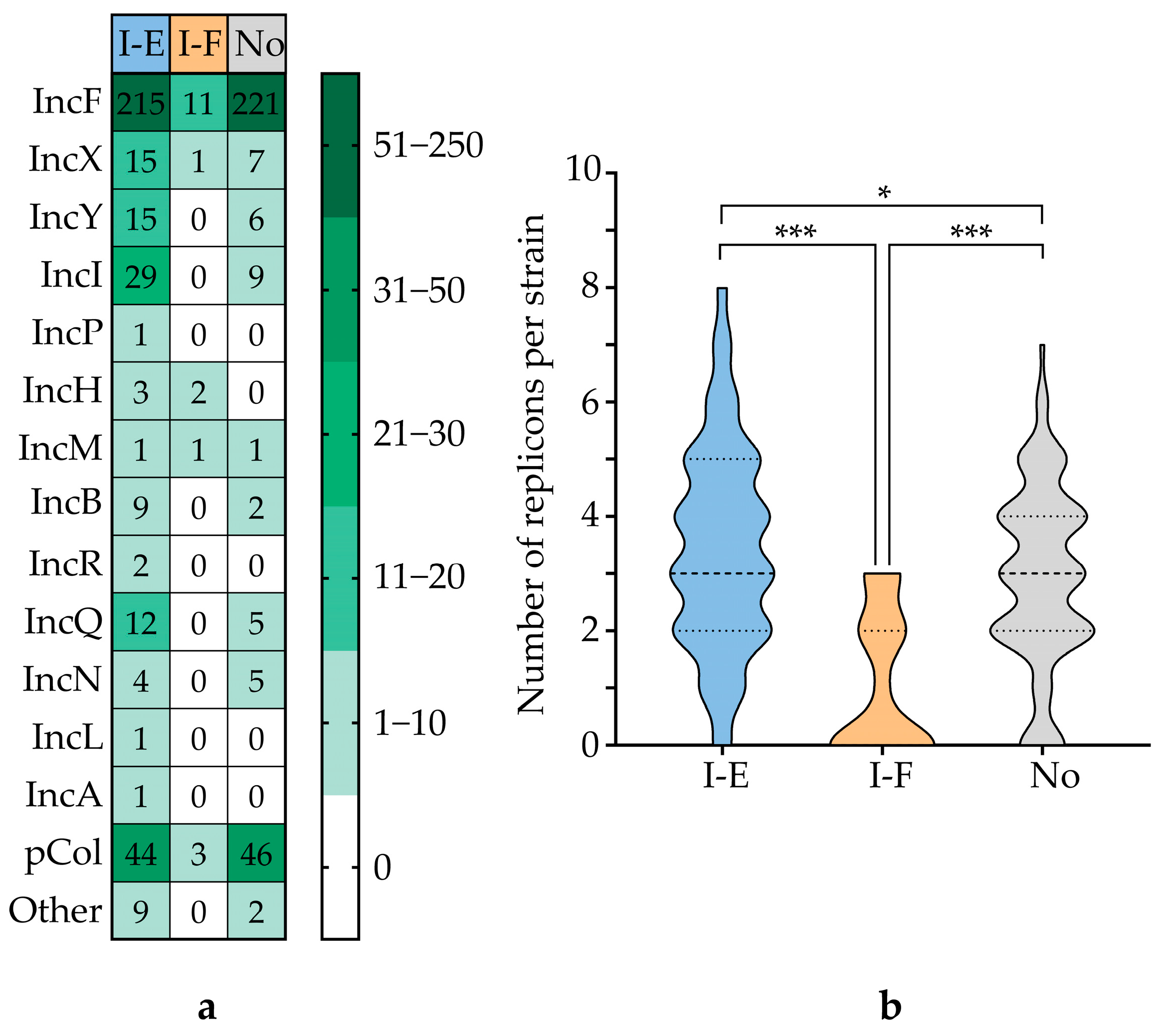

3.1. General Characteristics of the Strains

3.2. Identification and Characterization of CRISPR-Cas Systems

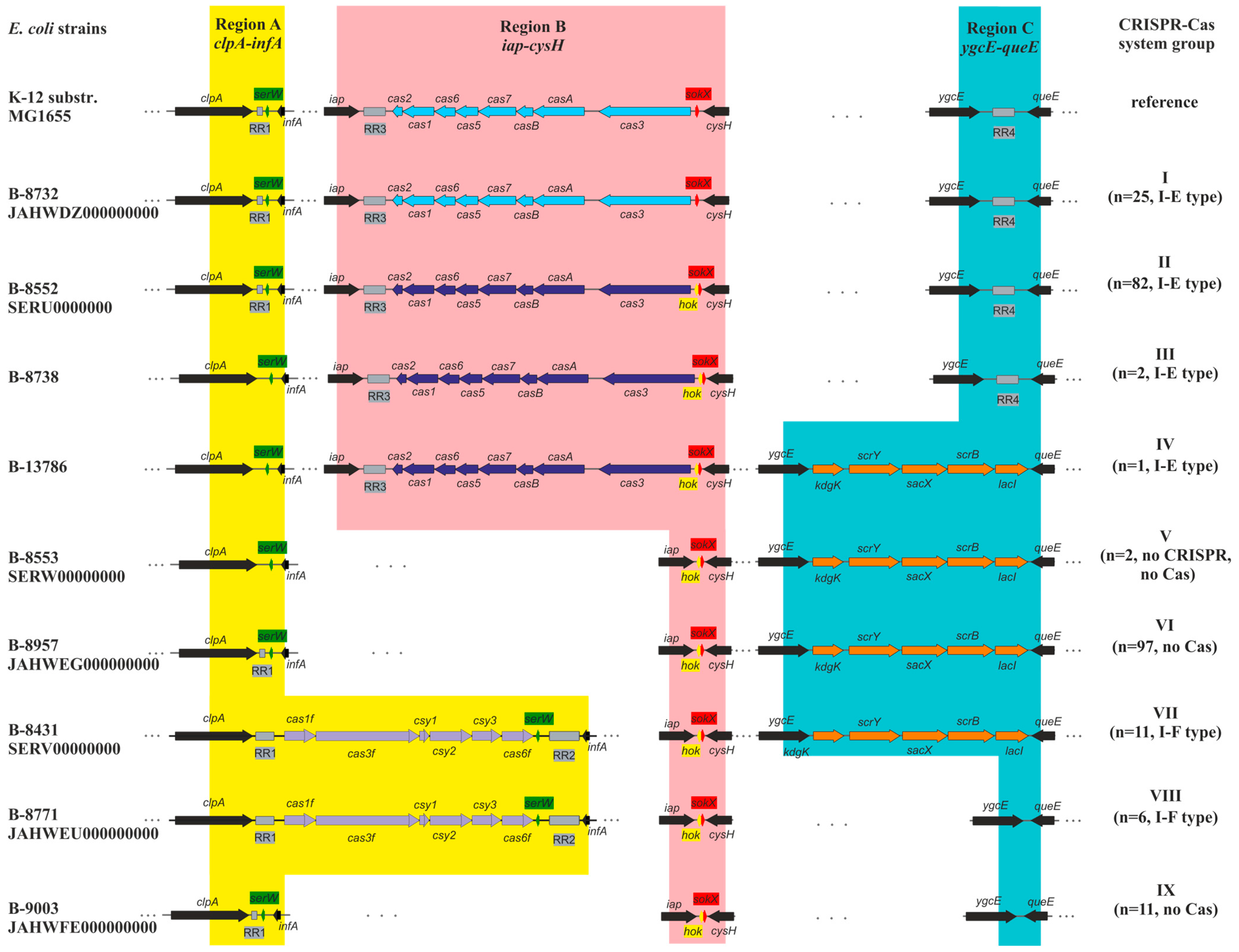

3.3. Types of CRISPR-Cas Systems

3.4. Analysis of the Repeat Regions (RRs)

3.4.1. Direct Repeats (DRs)

3.4.2. Spacer Sets

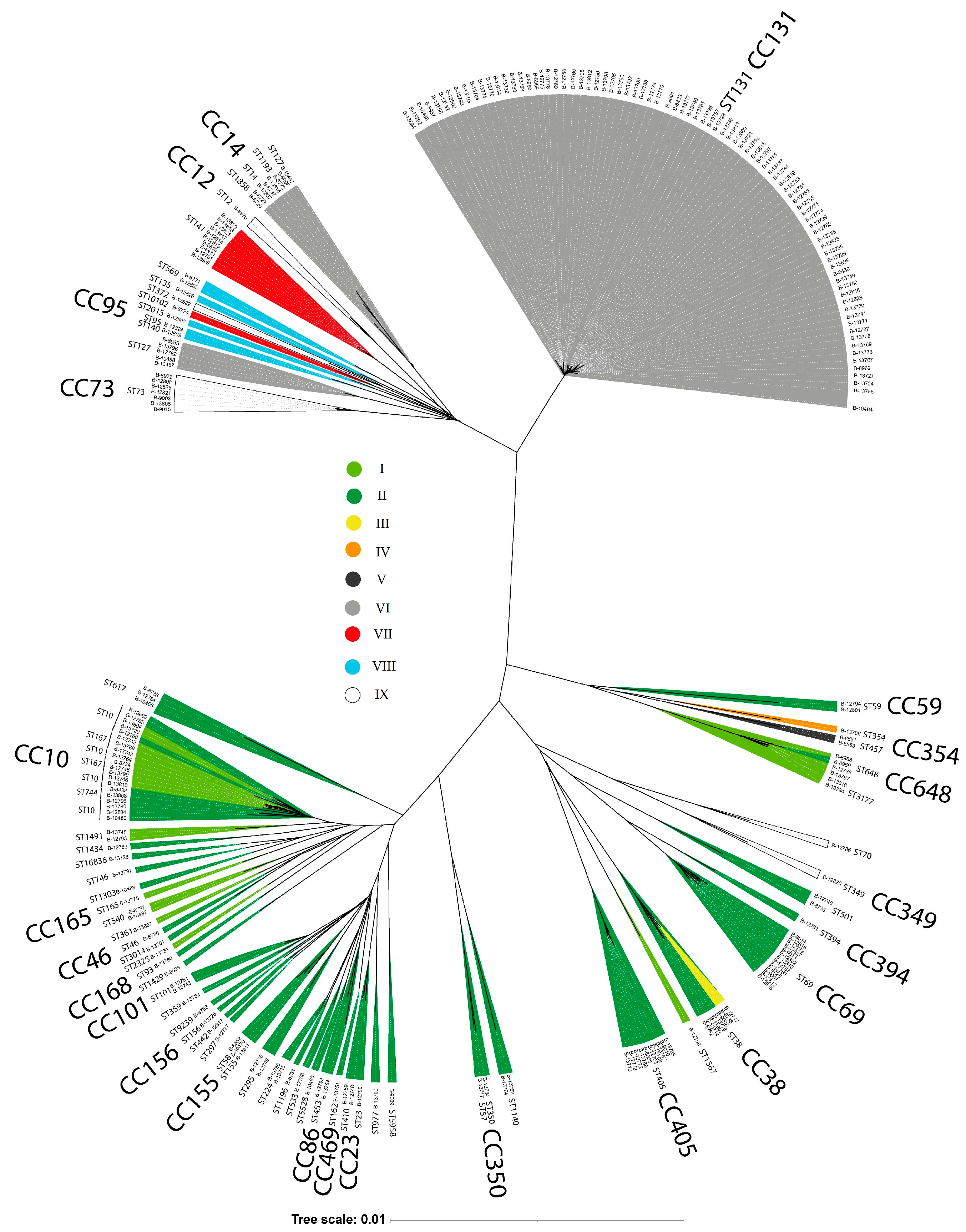

3.5. E. coli Phylogenetic Groups and CRISPR-Cas System Prevalence

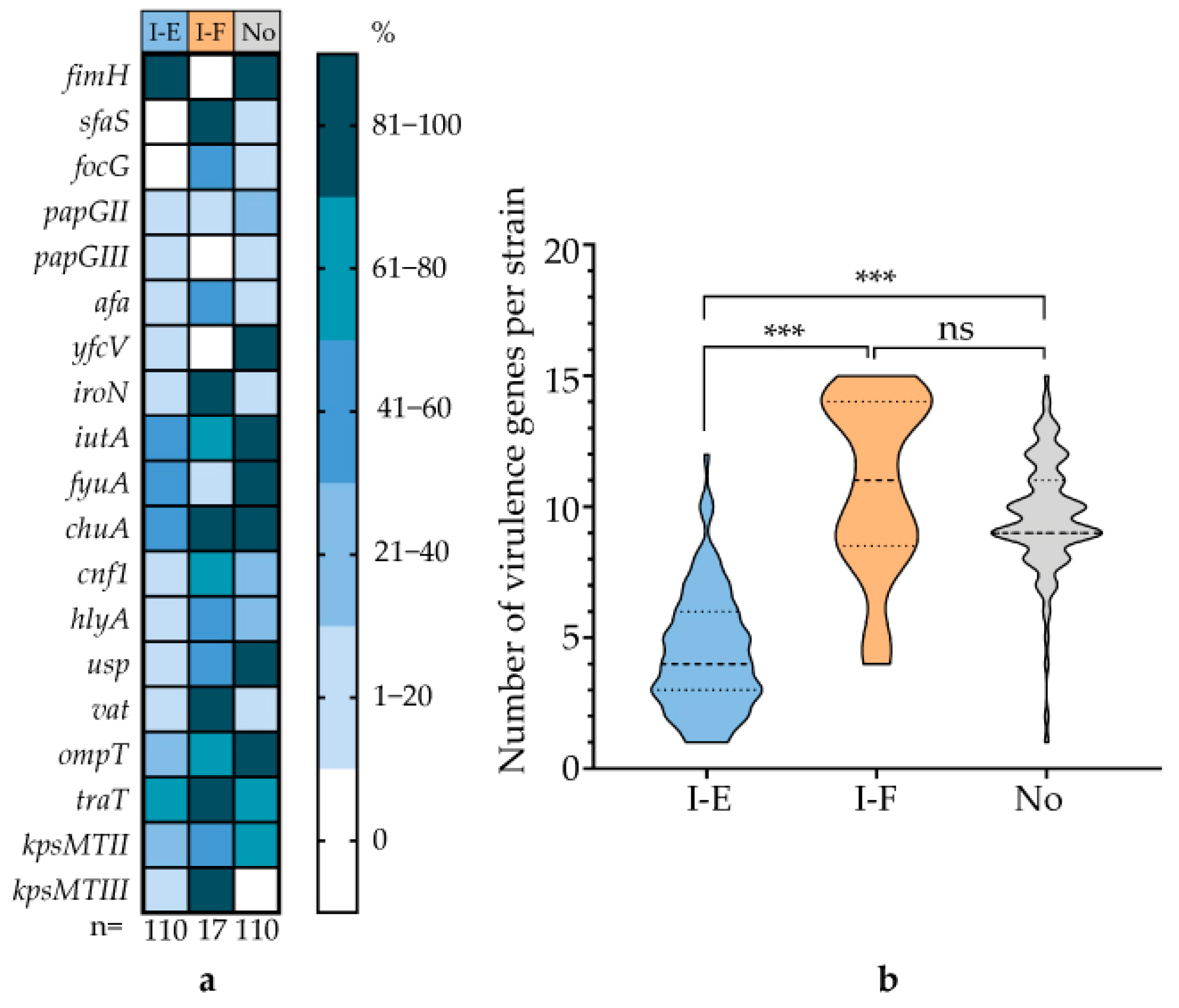

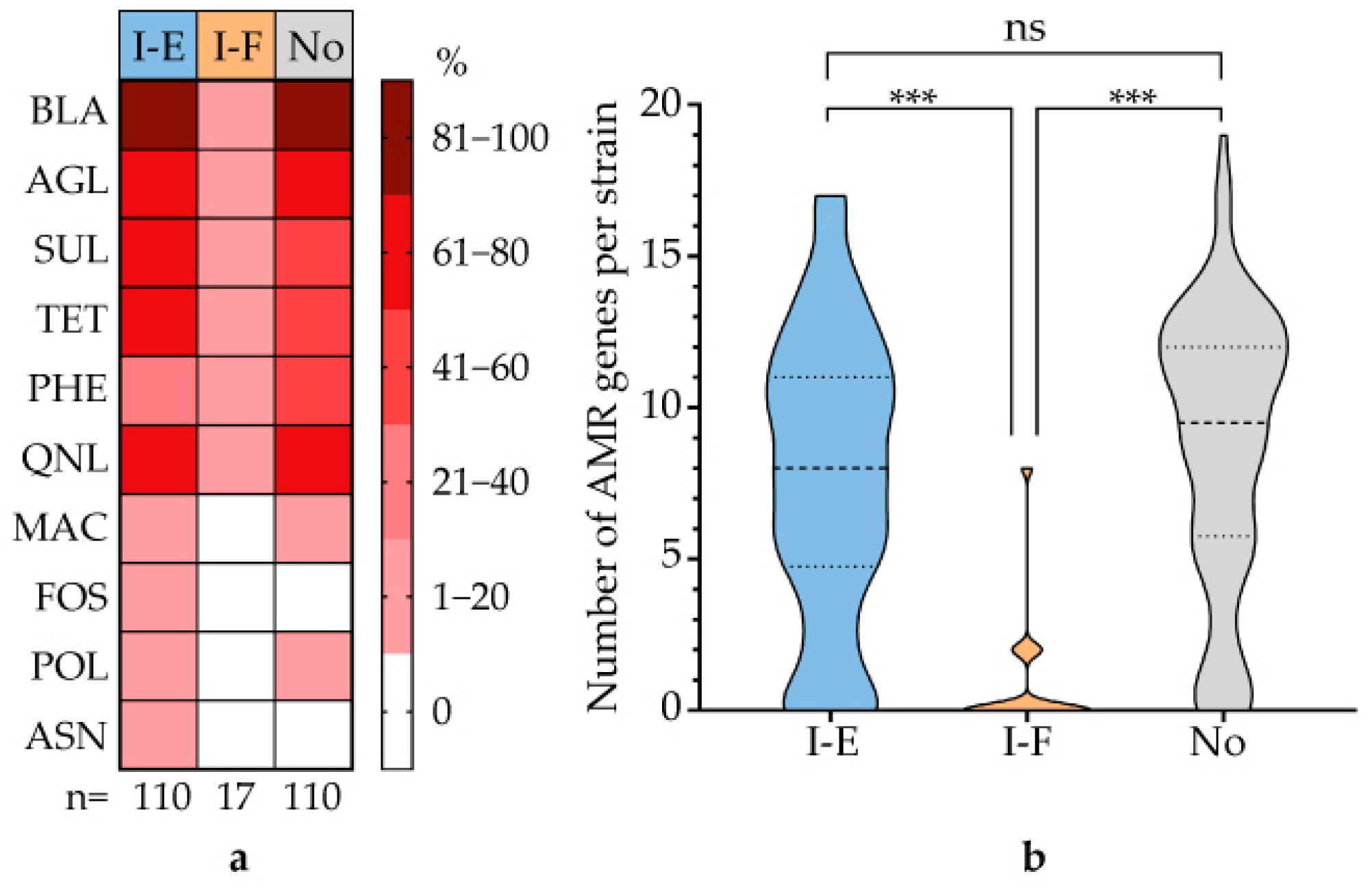

3.6. Correlation Between CRISPR-Cas System Type and Virulence Genes and AMR Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| Cas | CRISPR-associated Proteins |

| RRs | Repeat Regions |

| DRs | Direct Repeats |

| UPEC | Uropathogenic E. coli |

| UTI | Urinary Tract Infection |

| WGS | Whole-Genome Sequencing |

| ST | Sequence Type |

| CC | Clonal Complex |

References

- Timm, M.R.; Russell, S.K.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary tract infections: Pathogenesis, host susceptibility and emerging therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagaletsios, L.A.; Kikidou, E.; Galbenis, C.; Bitar, I.; Papagiannitsis, C.C. Exploring virulence characteristics of clinical Escherichia coli isolates from Greece. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitić, D.; Bolt, E.L.; Ivančić-Baće, I. CRISPR-Cas adaptation in Escherichia coli. Biosci. Rep. 2023, 43, BSR20221198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosterd, C.; Rousseau, G.M.; Moineau, S. A short overview of the CRISPR-Cas adaptation stage. Can. J. Microbiol. 2021, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K.S.; Wolf, Y.I.; Alkhnbashi, O.S.; Costa, F.; Shah, S.A.; Saunders, S.J.; Barrangou, R.; Brouns, S.J.J.; Charpentier, E.; Haft, D.H.; et al. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Semenova, E.; Severinov, K.; Fernández-García, L.; Benedik, M.J.; Maeda, T.; Wood, T.K. CRISPR-Cas controls cryptic prophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, E.G. The E. coli CRISPR-Cas conundrum: Are they functional immune systems or genomic singularities? EcoSal Plus 2025, 9, eesp00402020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Villaseñor, C.; Almendros, C.; García-Martínez, J.; Mojica, F.J. Diversity of CRISPR loci in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 2010, 156, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, M.B.; Shah, S.A.; Deng, L.; Thorsen, J.; Stokholm, J.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Schjørring, S.; Horvath, P.; Allard, A.; Nielsen, D.S.; et al. Escherichia coli CRISPR arrays from early life fecal samples preferentially target prophages. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K.S.; Haft, D.H.; Barrangou, R.; Brouns, S.J.; Charpentier, E.; Horvath, P.; Moineau, S.; Mojica, F.J.; Wolf, Y.I.; Yakunin, A.F.; et al. Evolution and classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchon, M.; Charpentier, S.; Clermont, O.; Rocha, E.P.; Denamur, E.; Branger, C. CRISPR distribution within the Escherichia coli species is not suggestive of immunity-associated diversifying selection. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 2460–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iordache, D.; Baci, G.M.; Căpriță, O.; Farkas, A.; Lup, A.; Butiuc-Keul, A. Correlation between CRISPR loci diversity in three enterobacterial taxa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P. The small, slow and specialized CRISPR and anti-CRISPR of Escherichia and Salmonella. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylova, Y.; Tyumentseva, M.; Karbyshev, K.; Tyumentsev, A.; Slavokhotova, A.; Smirnova, S.; Akinin, A.; Shelenkov, A.; Akimkin, V. Interrelation between pathoadaptability factors and Crispr-element patterns in the genomes of Escherichia coli isolates collected from healthy puerperant women in Ural region, Russia. Pathogens 2024, 13, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimi, K.; Takeshita, K.; Kodera, N.; Shibumura, S.; Yamauchi, Y.; Omatsu, M.; Umeda, K.; Kunihiro, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Mashimo, T. Dynamic mechanisms of CRISPR interference by Escherichia coli CRISPR-Cas3. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontheimer, E.J.; Barrangou, R. The bacterial origins of the CRISPR genome-editing revolution. Hum. Gene Ther. 2015, 26, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajkarimi, M.; Wexler, H.M. CRISPR-Cas systems in Bacteroides fragilis, an important pathobiont in the human gut microbiome. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 23, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheludchenko, M.S.; Huygens, F.; Stratton, H.; Hargreaves, M. CRISPR diversity in E. coli isolates from Australian animals, humans and environmental waters. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, D. CRISPR/Cas technologies and their applications in Escherichia coli. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 762676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Lee, Y.J. Relationship between CRISPR sequence type and antimicrobial resistance in avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Vet. Microbiol. 2022, 266, 109338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziuba, A.; Dzierżak, S.; Sodo, A.; Wawszczak-Kasza, M.; Zegadło, K.; Białek, J.; Zych, N.; Kiebzak, W.; Matykiewicz, J.; Głuszek, S.; et al. Comparative study of virulence potential, phylogenetic origin, CRISPR-Cas regions and drug resistance of Escherichia coli isolates from urine and other clinical materials. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1289683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clermont, O.; Gordon, D.; Denamur, E. Guide to the various phylogenetic classification schemes for Escherichia coli and the correspondence among schemes. Microbiology 2015, 161, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolaia, V.; Kaas, R.S.; Ruppe, E.; Roberts, M.C.; Schwarz, S.; Cattoir, V.; Philippon, A.; Allesoe, R.L.; Rebelo, A.R.; Florensa, A.R.; et al. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3491–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clausen, P.T.L.C.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Lund, O. Rapid and precise alignment of raw reads against redundant databases with KMA. BMC Bioinform. 2018, 19, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.; Cosentino, S.; Rasmussen, S.; Rundsten, C.; Hasman, H.; Marvig, R.; Jelsbak, L.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Ussery, D.; Aarestrup, F.; et al. Multilocus sequence typing of total genome sequenced bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, S.; Belmont, C.; Scheffler, A.W.; Ravi, K.; Kim, H.; Rubin-Saika, N.; Elises, M.; Soto, A.; Mahesh, P.A.; Chambers, H.; et al. Trends in uropathogenic Escherichia coli genotype and antimicrobial resistance from 2019 to 2022 in a San Francisco Public Hospital Network. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, K.B.; Amogne, W.; Alemayehu, H.; Bopegamage, S.; Eguale, T. The role of uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence factors in the development of urinary tract infection. J. Med. Life 2025, 18, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahian, S.; Graham, J.P.; Halaji, M. A review of the mechanisms that confer antibiotic resistance in pathotypes of E. coli. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1387497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almendros, C.; Mojica, F.J.; Díez-Villaseñor, C.; Guzmán, N.M.; García-Martínez, J. CRISPR-Cas functional module exchange in Escherichia coli. mBio 2014, 5, e00767–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, E.; Almendros, C.; Mojica, F.J.M.; Guzmán, N.M.; García-Martínez, J. CRISPR content correlates with the pathogenic potential of Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131935, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | var. B-8552/var. K-12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Length, bp | GC-Content, % | Gene QC/PI, % | Protein QC/PI, % | |

| cas3 | 2700/2667 | 50/45 | 0/0 | 87/29 |

| casA | 1563/1509 | 50/44 | 1/94 | 53/23 |

| casB | 537/483 | 52/46 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| cas7 | 1056/1092 | 51/44 | 0/0 | 82/31 |

| cas5 | 747/675 | 55/48 | 0/0 | 66/32 |

| cas6 | 651/600 | 55/45 | 0/0 | 99/29 |

| cas1 | 924/918 | 52/51 | 90/73 | 98/84 |

| cas2 | 294/285 | 48/46 | 99/75 | 90/86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Slukin, P.V.; Fursov, M.V.; Volkov, D.V.; Sizova, A.A.; Detushev, K.V.; Dyatlov, I.A.; Fursova, N.K. Diversity of CRISPR-Cas Systems Identified in Urological Escherichia coli Strains. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2846. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122846

Slukin PV, Fursov MV, Volkov DV, Sizova AA, Detushev KV, Dyatlov IA, Fursova NK. Diversity of CRISPR-Cas Systems Identified in Urological Escherichia coli Strains. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2846. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122846

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlukin, Pavel V., Mikhail V. Fursov, Daniil V. Volkov, Angelika A. Sizova, Konstantin V. Detushev, Ivan A. Dyatlov, and Nadezhda K. Fursova. 2025. "Diversity of CRISPR-Cas Systems Identified in Urological Escherichia coli Strains" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2846. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122846

APA StyleSlukin, P. V., Fursov, M. V., Volkov, D. V., Sizova, A. A., Detushev, K. V., Dyatlov, I. A., & Fursova, N. K. (2025). Diversity of CRISPR-Cas Systems Identified in Urological Escherichia coli Strains. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2846. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122846