Unveiling Acinetobacter endophylla sp. nov.: A Specialist Endophyte from Peganum harmala with Distinct Genomic and Metabolic Traits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Habitat and Isolation of Endophytic Bacteria

2.2. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatics Analysis

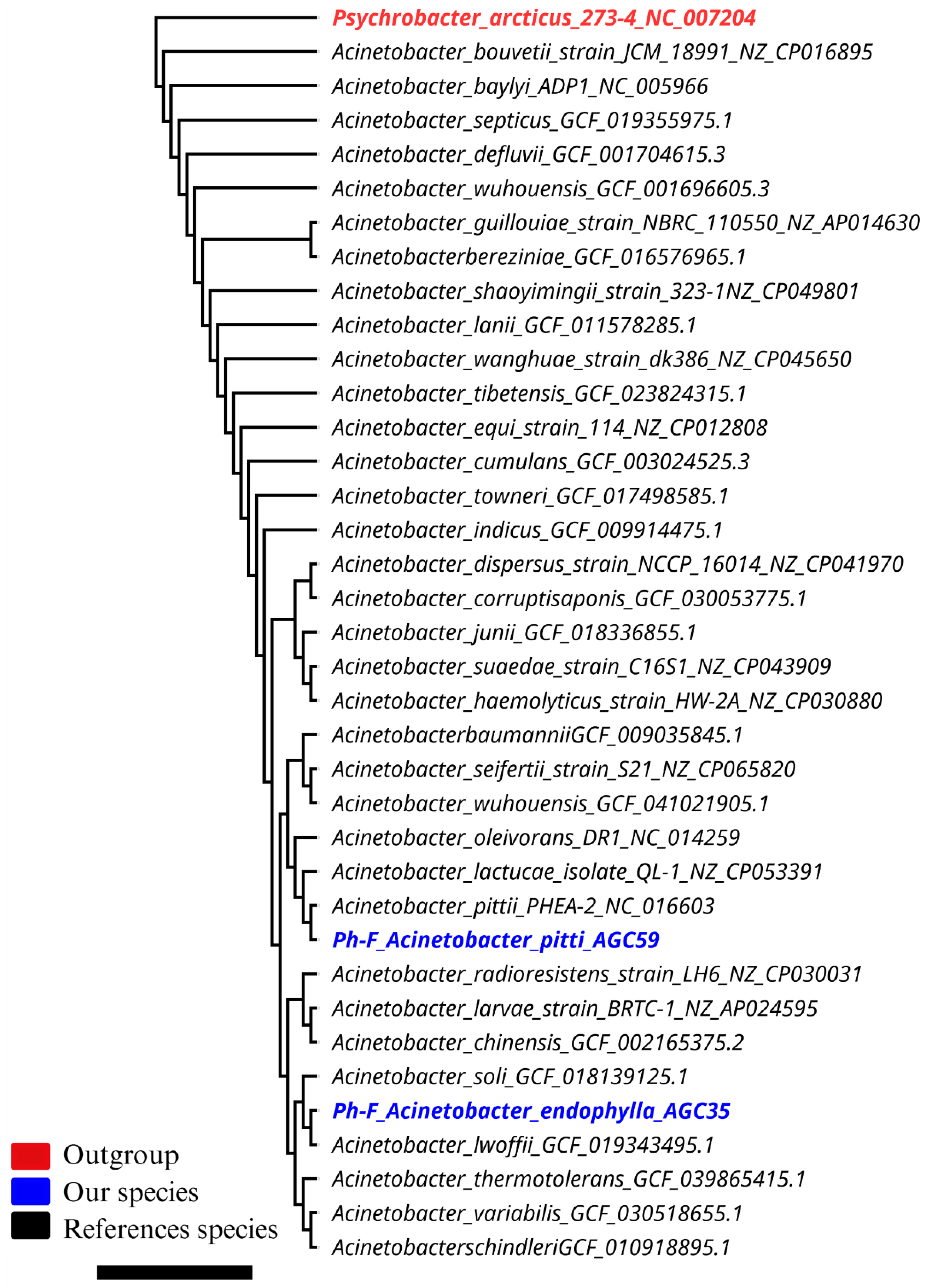

2.4. Taxonomic Assignment and Phylogenomic Analysis

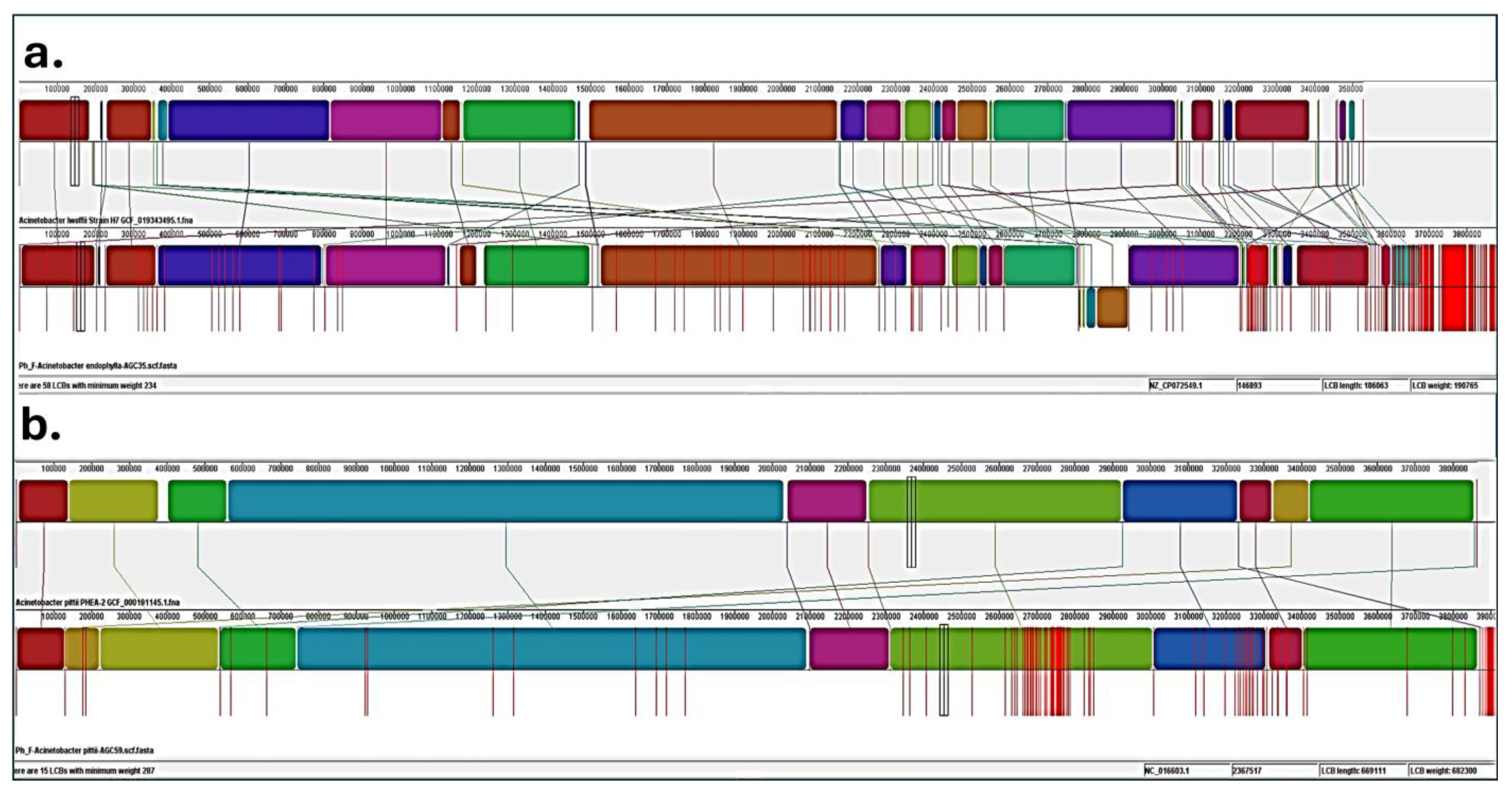

2.5. Functional Annotation, Genome Visualization, and Comparative Genomics

2.6. Phenotypic Profiling

2.7. Plant-Growth-Promoting (PGP) Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Bacterial Endophytes

3.2. Genome Insights of Acinetobacter Strains

3.2.1. Phylogenomics and Genome Structure

3.2.2. Genome Assembly, Quality, and Taxonomic Assignment

3.3. Functional and Metabolic Potential Abilities

3.4. Nomenclature and Biochemical Profiling of Novel Acinetobacter

Acinetobacter endophylla sp. nov.

- Etymology: endophylla (fem. adj.) from the Greek endon (“inside”) and phyton (“plant”), referring to its endophytic lifestyle within plant tissues.

- Species name: Acinetobacter endophylla sp. nov.

- Type strain: AGC 35T (=CCMM B1335T).

- Accession numbers: 16S rRNA gene, PV739381; whole genome, SRR29855794.

- BioProject: PRJNA1133887; Biosample: SRP520430.

- DNA G + C content: 42.58%; Genome size: 3.75 Mb.

- ANI/closest relative: 96%. dDDH: 64.5%.

3.5. Biochemical, and Plant-Growth-Promoting (PGP) Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Faure, D.; Simon, J.-C.; Heulin, T. Holobiont: A conceptual framework to explore the eco-evolutionary and functional implications of host–microbiota interactions in all ecosystems. New Phytol. 2018, 218, 1321–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardoim, P.R.; van Overbeek, L.S.; Elsas, J.D. Properties of bacterial endophytes and their proposed role in plant growth. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compant, S.; Samad, A.; Faist, H.; Sessitsch, A. A review on the plant microbiome: Ecology, functions, and emerging trends in microbial application. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 19, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamadalieva, N.Z.; Ashour, M.L.; Mamedov, N.A. Peganum harmala: Phytochemistry, Traditional Uses, and Biological Activities. In Biodiversity, Conservation and Sustainability in Asia; Öztürk, M., Khan, S.M., Altay, V., Efe, R., Egamberdieva, D., Khassanov, F.O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 721–744. [Google Scholar]

- Sodaeizadeh, H.; Rafieiolhossaini, M.; Havlík, J.; Van Damme, P. Allelopathic activity of different plant parts of Peganum harmala L. and identification of their growth inhibitors substances. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 59, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muleshkova, T.; Bazukyan, I.; Papadimitriou, K.; Gotcheva, V.; Angelov, A.; Dimov, S.G. Exploring the Multifaceted Genus Acinetobacter: The Facts, the Concerns and the Oppoptunities the Dualistic Geuns Acinetobacter. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 35, e2411043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Lou, K.; Li, C. Growth promotion effects of the endophyte Acinetobacter johnsonii strain 3-1 on sugar beet. Symbiosis 2011, 54, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, K.; Soylu, S. Characterization of plant growth-promoting traits and antagonistic potentials of endophytic bacteria from bean plants against Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola. Bitki Koruma Bülteni 2019, 59, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, S.; Pu, Z.; Cao, R.; Wu, S.; Xie, Z.; Wang, D. Genomic analysis and phytoprobiotic characteristics of Acinetobacter pittii P09: A p-hydroxybenzoic acid-degrading plant-growth promoting rhizobacteria. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohadi, M.; Forootanfar, H.; Dehghannoudeh, G.; Eslaminejad, T.; Ameri, A.; Shakibaie, M.; Adeli-Sardou, M. Antimicrobial, anti-biofilm, and anti-proliferative activities of lipopeptide biosurfactant produced by Acinetobacter junii B6. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 138, 103806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, H.-M.; Yuan, J.-L.; Xu, L.; Sun, J.-Q. A comprehensive genomic analysis provides insights on the high environmental adaptability of Acinetobacter strains. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1177951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, D.; Latorre, K.; Muñoz-Torres, P.; Cárdenas, S.; Jofré-Quispe, A.; López-Cepeda, J.; Bustos, L.; Balada, C.; Argaluza, M.F.; González, P.; et al. Diversity of Culturable Bacteria from Endemic Medicinal Plants of the Highlands of the Province of Parinacota, Chile. Biology 2023, 12, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-H.; Guo, J.-W.; Salam, N.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Han, J.; Mohamad, O.A.; Li, W.-J. Culturable endophytic bacteria associated with medicinal plant Ferula songorica: Molecular phylogeny, distribution and screening for industrially important traits. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.O.; Al-Zahrani, D.A.; Hussein, R.M.; Jalal, R.S.; Abulfaraj, A.A.; Majeed, M.A.; Baeshen, M.N.; Al-Hejin, A.M.; Baeshen, N.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. Biodiversity in Bacterial Phyla Composite in Arid Soils of the Community of Desert Medicinal Plant Rhazya stricta. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2020, 32, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, E.; Massa, N.; Toumatia, O.; Novello, G.; Cesaro, P.; Todeschini, V.; Boatti, L.; Mignone, F.; Titouah, H.; Zitouni, A.; et al. Climatic Zone and Soil Properties Determine the Biodiversity of the Soil Bacterial Communities Associated to Native Plants from Desert Areas of North-Central Algeria. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora-Leiva, L.; Soto, J.; Román-Figueroa, C.; Peña, F.; Univaso, L.; Paneque, M. Characterization of bacterial diversity associated with a Salar de Atacama native plant Nitrophila atacamensis. Environ. Microbiome 2025, 20, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, S.M.; Al-Sulami, N.; Al-Amrah, H.; Anwar, Y.; Gadah, O.A.; Bahamdain, L.A.; Al-Matary, M.; Alamri, A.M.; Bahieldin, A. Metagenomic Characterization of the Maerua crassifolia Soil Rhizosphere: Uncovering Microbial Networks for Nutrient Acquisition and Plant Resilience in Arid Ecosystems. Genes. 2025, 16, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Dubey, A.K. Diversity and Applications of Endophytic Actinobacteria of Plants in Special and Other Ecological Niches. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Si Mhand, K.; Mouhib, S.; Radouane, N.; Errafii, K.; Kadmiri, I.M.; Andrade-Molina, D.M.; Fernández-Cadena, J.C.; Hijri, M. Two Novel Microbacterium Species Isolated from Citrullus colocynthis L. (Cucurbitaceae), a Medicinal Plant from Arid Environments. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdappa, S.; Jagannath, S.; Konappa, N.; Udayashankar, A.C.; Jogaiah, S. Detection and Characterization of Antibacterial Siderophores Secreted by Endophytic Fungi from Cymbidium aloifolium. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szűcs, Z.; Plaszkó, T.; Cziáky, Z.; Kiss-Szikszai, A.; Emri, T.; Bertóti, R.; Sinka, L.T.; Vasas, G.; Gonda, S. Endophytic fungi from the roots of horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) and their interactions with the defensive metabolites of the glucosinolate—myrosinase—isothiocyanate system. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhayanithy, G.; Subban, K.; Chelliah, J. Diversity and biological activities of endophytic fungi associated with Catharanthus roseus. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayatilake, P.L.; Munasinghe, H. Antimicrobial Activity of Cultivable Endophytic and Rhizosphere Fungi Associated with “Mile-a-Minute,” Mikania cordata (Asteraceae). BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 5292571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Cruz, R.; Tpia Vázquez, I.; Batista-García, R.A.; Méndez-Santiago, E.W.; Sánchez-Carbente, M.D.R.; Leija, A.; Lira-Ruan, V.; Hernández, G.; Wong-Villarreal, A.; Folch-Mallol, J.L. Isolation and characterization of endophytes from nodules of Mimosa pudica with biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Res. 2019, 218, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becard, G.; Fortin, J.A. Early events of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza formation on Ri T-DNA transformed roots. New Phytol. 1988, 108, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llop, P.; Caruso, P.; Cubero, J.; Morente, C.; López, M.a.M. A simple extraction procedure for efficient routine detection of pathogenic bacteria in plant material by polymerase chain reaction. J. Microbiol. Methods 1999, 37, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, F.; Lee, S.-J.; St-Arnaud, M.; Hijri, M. Salix purpurea and Eleocharis obtusa Rhizospheres Harbor a Diverse Rhizospheric Bacterial Community Characterized by Hydrocarbons Degradation Potentials and Plant Growth-Promoting Properties. Plants 2021, 10, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducousso-Détrez, A.; Lahrach, Z.; Fontaine, J.; Lounès-Hadj Sahraoui, A.; Hijri, M. Cultural techniques capture diverse phosphate-solubilizing bacteria in rock phosphate-enriched habitats. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1280848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, B.; Rood, J.; Singer, E. BBMerge—Accurate paired shotgun read merging via overlap. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, P.; Ng, K.L.; Krogh, A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimin, A.V.; Marçais, G.; Puiu, D.; Roberts, M.; Salzberg, S.L.; Yorke, J.A. The MaSuRCA genome assembler. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2669–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikheenko, A.; Prjibelski, A.; Saveliev, V.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A. Versatile genome assembly evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i142–i150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P.A. metaSPAdes: A new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-W.; Simmons, B.A.; Singer, S.W. MaxBin 2.0: An automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, C.M.K.; Probst, A.J.; Sharrar, A.; Thomas, B.C.; Hess, M.; Tringe, S.G.; Banfield, J.F. Recovery of genomes from metagenomes via a dereplication, aggregation and scoring strategy. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, K.A.; Bray, J.E.; Maiden, M.C.J. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018, 3, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, M.; Rosselló-Móra, R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19126–19131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.-P.; Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramaki, T.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; Endo, H.; Ohkubo, K.; Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Ogata, H. KofamKOALA: KEGG Ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2251–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeek, R.; Olson, R.; Pusch, G.D.; Olsen, G.J.; Davis, J.J.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Gerdes, S.; Parrello, B.; Shukla, M.; et al. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D206–D214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, T.; Ramana, L.N.; Sharma, T.K. Current Advancements and Future Road Map to Develop ASSURED Microfluidic Biosensors for Infectious and Non-Infectious Diseases. Biosensors 2022, 12, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morobane, D.M.; Tshishonga, K.; Serepa-Dlamini, M.H. Draft Genome Sequence of Pantoea sp. Strain MHSD4, a Bacterial Endophyte With Bioremediation Potential. Evol. Bioinform. Online 2024, 20, 11769343231217908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Augustijn, H.E.; Reitz, Z.L.; Biermann, F.; Alanjary, M.; Fetter, A.; Terlouw, B.R.; Metcalf, W.W.; Helfrich, E.J.N.; et al. antiSMASH 7.0: New and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W46–W50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.R.; Enns, E.; Marinier, E.; Mandal, A.; Herman, E.K.; Chen, C.-y.; Graham, M.; Van Domselaar, G.; Stothard, P. Proksee: In-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W484–W492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.L.; Mullet, J.; Hindi, F.; Stoll, J.E.; Gupta, S.; Choi, M.; Keenum, I.; Vikesland, P.; Pruden, A.; Zhang, L. mobileOG-db: A Manually Curated Database of Protein Families Mediating the Life Cycle of Bacterial Mobile Genetic Elements. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e00991-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, A.G.; Waglechner, N.; Nizam, F.; Yan, A.; Azad, M.A.; Baylay, A.J.; Bhullar, K.; Canova, M.J.; De Pascale, G.; Ejim, L.; et al. The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3348–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emenike, C.U.; Agamuthu, P.; Fauziah, S.H. Blending Bacillus sp., Lysinibacillus sp. and Rhodococcus sp. for optimal reduction of heavy metals in leachate contaminated soil. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, C.S. An efficient microbiological growth medium for screening phosphate solubilizing microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 170, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, V.S.; Maurya, B.R.; Verma, J.P.; Aeron, A.; Kumar, A.; Kim, K.; Bajpai, V.K. Potassium solubilizing rhizobacteria (KSR): Isolation, identification, and K-release dynamics from waste mica. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 81, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Sharma, M.P.; Ramesh, A.; Joshi, O.P. Characterization of zinc-solubilizing Bacillus isolates and their potential to influence zinc assimilation in soybean seeds. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 22, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bist, V.; Niranjan, A.; Ranjan, M.; Lehri, A.; Seem, K.; Srivastava, S. Silicon-Solubilizing Media and Its Implication for Characterization of Bacteria to Mitigate Biotic Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patten, C.L.; Glick, B.R. Role of Pseudomonas putida indoleacetic acid in development of the host plant root system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 3795–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rennie, R. A single medium for the isolation of acetylene-reducing (dinitrogen-fixing) bacteria from soils. Can. J. Microbiol. 1981, 27, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, E.; Hazra, A.; Dutta, M.; Bose, R.; Dutta, A.; Dandapat, M.; Guha, T.; Mandal Biswas, S. Novel report of Acinetobacter johnsonii as an indole-producing seed endophyte in Tamarindus indica L. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Duan, W.; Ran, Z.; Chen, X.; Yu, H.; Fang, L.; Guo, L.; Zhou, J. Diversity and correlation analysis of endophytes and metabolites of Panax quinquefolius L. in various tissues. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 275, Correction in BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laha, A.; Sarkar, S.; Sengupta, S.; Das, A.; Paul, S.; Bhattacharyya, S. Unraveling the potential of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus for arsenic resistance and plant growth promotion in contaminated lentil field. South Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 168, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snellman, E.A.; Colwell, R.R. Acinetobacter lipases: Molecular biology, biochemical properties and biotechnological potential. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 31, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampaloni, C.; Mattei, P.; Bleicher, K.; Winther, L.; Thäte, C.; Bucher, C.; Adam, J.-M.; Alanine, A.; Amrein, K.E.; Baidin, V.; et al. A novel antibiotic class targeting the lipopolysaccharide transporter. Nature 2024, 625, 566–571, Correction in Nature 2024, 631, E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujumdar, S.; Joshi, P.; Karve, N. Production, characterization, and applications of bioemulsifiers (BE) and biosurfactants (BS) produced by Acinetobacter spp.: A review. J. Basic Microbiol. 2019, 59, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Atrouni, A.; Joly-Guillou, M.L.; Hamze, M.; Kempf, M. Reservoirs of Non-baumannii Acinetobacter Species. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, A.; Radolfova-Krizova, L.; Maixnerova, M.; Nemec, M.; Shestivska, V.; Spanelova, P.; Kyselkova, M.; Wilharm, G.; Higgins, P.G. Acinetobacter amyesii sp. nov., widespread in the soil and water environment and animals. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 005642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, K.; Han, Z.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Shao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, L. Microbial diversity and biogeochemical cycling potential in deep-sea sediments associated with seamount, trench, and cold seep ecosystems. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1029564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Park, W. Acinetobacter species as model microorganisms in environmental microbiology: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 2533–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethu, C.S.; Saravanakumar, C.; Purvaja, R.; Robin, R.S.; Ramesh, R. Oil-Spill Triggered Shift in Indigenous Microbial Structure and Functional Dynamics in Different Marine Environmental Matrices. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouky, A.-E.-H. Acinetobacter: Environmental and biotechnological applications. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2003, 2, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Luo, H.; Chen, B.; Chen, J.; Fang, J.; Song, Z. A novel eco-friendly Acinetobacter strain A1-4-2 for bioremediation of aquatic pollutants. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahal, U.; Paul, K.; Gupta, S. The multifaceted genus Acinetobacter: From infection to bioremediation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.J.; Arisdakessian, C.; Petelo, M.; Keliipuleole, K.; Tachera, D.K.; Okuhata, B.K.; Dulai, H.; Frank, K.L. Geology and land use shape nitrogen and sulfur cycling groundwater microbial communities in Pacific Island aquifers. ISME Commun. 2023, 3, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, V.A.; Renner, T.; Baker, L.J.; Hendry, T.A. Genome evolution following an ecological shift in nectar-dwelling Acinetobacter. mSphere 2025, 10, e0101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.M.; Frixione, N.J.; Burkert, A.C.; Dinsdale, E.A.; Vannette, R.L. Microbial abundance, composition, and function in nectar are shaped by flower visitor identity. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bacterial Species (Strain) | Taxonomy Classification | Genome Comparisons | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLST Analysis | Closest Relative | MLST Analysis | Closest Relative | MLST Analysis | |

| Acinetobacter endophylla sp. nov. (AGC35) | 92% | Acinetobacter lwoffii | 92% | Acinetobacter lwoffii | 92% |

| Acinetobacter pitti (AGC59) | 100% | Acinetobacter pitti | 100% | Acinetobacter pitti | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mouhib, S.; Ait Si Mhand, K.; Radouane, N.; Errafii, K.; Kadmiri, I.M.; Andrade-Molina, D.; Fernández-Cadena, J.C.; Hijri, M. Unveiling Acinetobacter endophylla sp. nov.: A Specialist Endophyte from Peganum harmala with Distinct Genomic and Metabolic Traits. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122843

Mouhib S, Ait Si Mhand K, Radouane N, Errafii K, Kadmiri IM, Andrade-Molina D, Fernández-Cadena JC, Hijri M. Unveiling Acinetobacter endophylla sp. nov.: A Specialist Endophyte from Peganum harmala with Distinct Genomic and Metabolic Traits. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122843

Chicago/Turabian StyleMouhib, Salma, Khadija Ait Si Mhand, Nabil Radouane, Khaoula Errafii, Issam Meftah Kadmiri, Derly Andrade-Molina, Juan Carlos Fernández-Cadena, and Mohamed Hijri. 2025. "Unveiling Acinetobacter endophylla sp. nov.: A Specialist Endophyte from Peganum harmala with Distinct Genomic and Metabolic Traits" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122843

APA StyleMouhib, S., Ait Si Mhand, K., Radouane, N., Errafii, K., Kadmiri, I. M., Andrade-Molina, D., Fernández-Cadena, J. C., & Hijri, M. (2025). Unveiling Acinetobacter endophylla sp. nov.: A Specialist Endophyte from Peganum harmala with Distinct Genomic and Metabolic Traits. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122843