Evaluation and Comparison of the UV-LED Action Spectra for Photochemical Disinfection of Coliphages and Human Pathogenic Viruses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phage, Virus, and Host Cell Strains

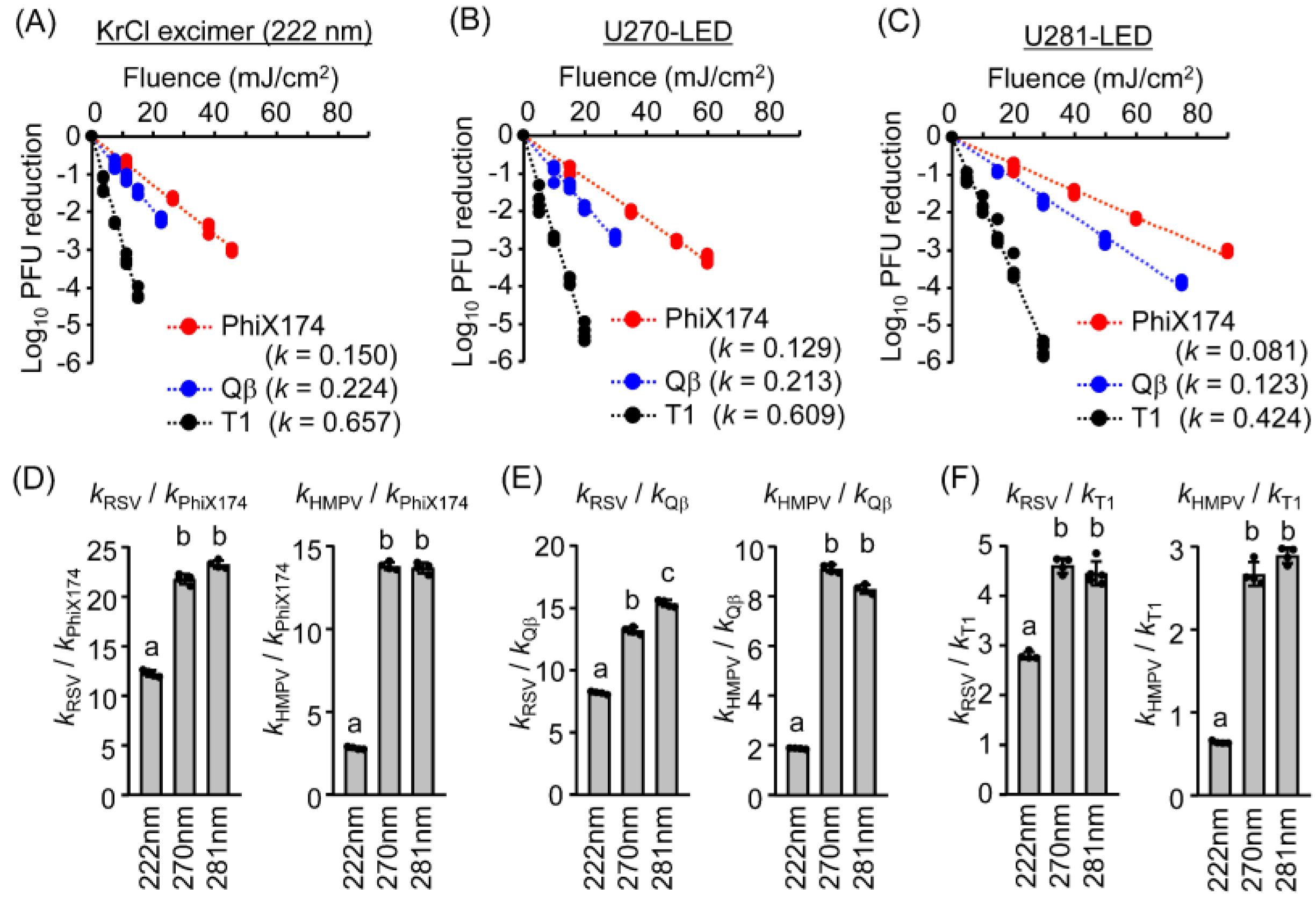

2.2. Irradiation of Phage/Virus Suspensions Using UV Lamps and LEDs

2.3. Measurements of Phage/Virus Infectivity Using Plaque-Forming Assay

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Standardized Irradiation Systems Were Validated Based on Their Virucidal Efficiency Against the MS2 Coliphage

| Light Source | Peak Wavelength of LEDs (nm) | Fluence (mJ/cm2) | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log10 Infectivity Reduction | |||||

| −1 | −2 | −3 | |||

| LED | 281.3 | 23.9 | 48.2 | - | This study |

| 280 | 24 | 46 | 73 | Oguma et al. [28] | |

| 279.1 | 23.0 | 46.3 | - | This study | |

| 275 | 25 | 55 | - | Bowker et al. [29] | |

| 269.3 | 16.1 | 33.5 | - | This study | |

| 265 | 22 | 59 | 93 | Oguma et al. [28] | |

| 265 | 16 | 35 | - | Sholtes et al. [30] | |

| 265 | 16 | 33 | 52 | Song et al. [31] | |

| 255 | 19 | 43 | 72 | Simons et al. [32] | |

| 255 | 25 | 50 | - | Bowker et al. [29] | |

| 253.3 | 19.7 | 41.1 | 62.6 | This study | |

| LP-Hg lamp | 254 | 29.4 | - | - | Weng et al. [33] |

| 254 | 31.1 | - | - | Zyara et al. [34] | |

| 253.44 | 28.4 | - | - | This study | |

| KrCl excimer lamp | 222 | 6.5 | 13.6 | 21,8 | Hull et al. [35] |

| 222 | 7.4 | 14.7 | 22.1 | Beck et al. [6] | |

| 222.03 | 11.1 | 21.6 | 32.1 | This study | |

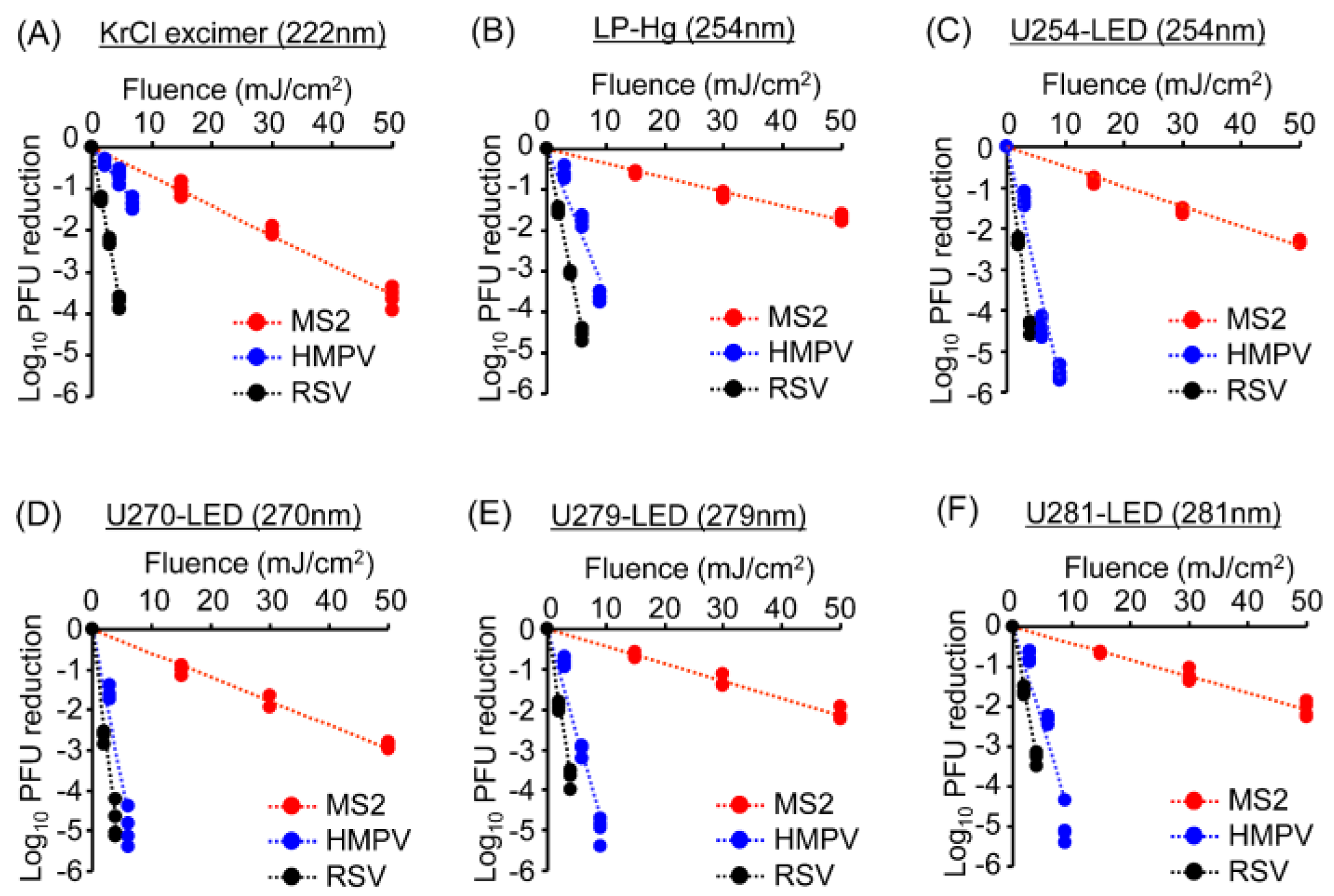

3.2. UV Sensitivities of the MS2 Coliphage and Viruses Differed Under Standardized Irradiation

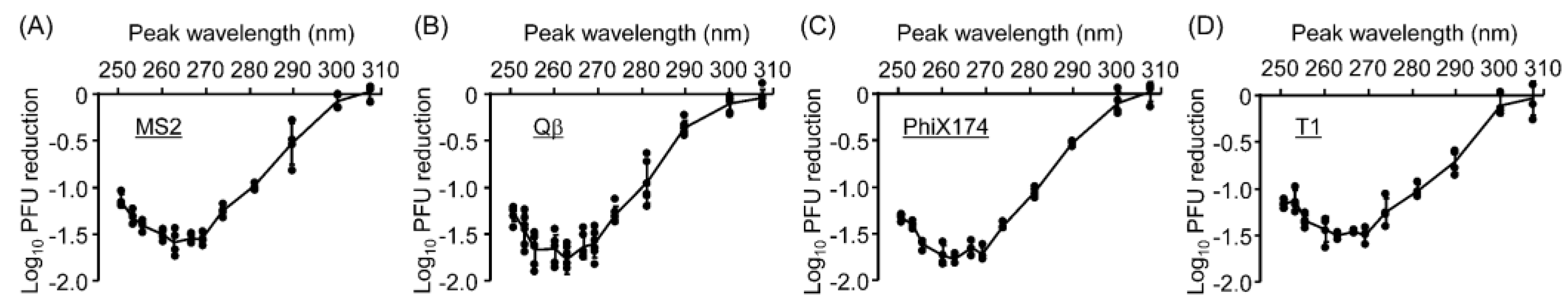

3.3. UV Sensitivities of Coliphages and Viruses Differed Across Wavelengths

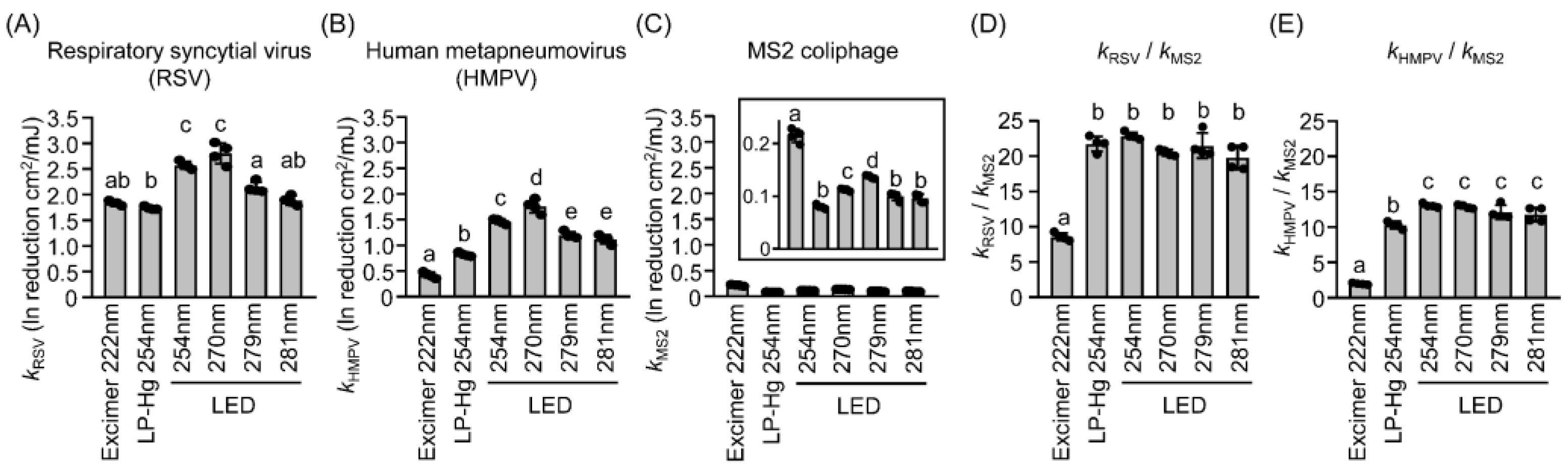

3.4. The UV Action Spectra for Virucidal Efficiency Were Similar for Coliphages and Mammalian Viruses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| dsDNA | Double-stranded DNA |

| dsRNA | Double-stranded RNA |

| HMPV | Human metapneumovirus |

| JCSS | Japan Calibration Service System |

| KrCl | Krypton–chloride |

| LED | Light-emitting diode |

| LP-Hg | Low-pressure mercury |

| NBRC | Biological Resource Center |

| NITE | National Institute of Technology and Evaluation |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PFU | Plaque-forming unit |

| RSV | Respiratory syncytial virus |

| ssDNA | Single-stranded DNA |

| ssRNA | Single-stranded RNA |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| UV-LED | UV-light emitting diode |

| UVGI | UV germicidal irradiation |

References

- Kampf, G. Efficacy of Ethanol against Viruses in Hand Disinfection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 98, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutala, W.A.; Weber, D.J. Best Practices for Disinfection of Noncritical Environmental Surfaces and Equipment in Health Care Facilities: A Bundle Approach. Am. J. Infect. Control 2019, 47, A96–A105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Gundy, P.M.; Gerba, C.P.; Sobsey, M.D.; Linden, K.G. UV Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 across the UVC Spectrum: KrCl* Excimer, Mercury-Vapor, and Light-Emitting-Diode (LED) Sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e0153221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishisaka-Nonaka, R.; Mawatari, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Kojima, M.; Shimohata, T.; Uebanso, T.; Nakahashi, M.; Emoto, T.; Akutagawa, M.; Kinouchi, Y.; et al. Irradiation by Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes Inactivates Influenza a Viruses by Inhibiting Replication and Transcription of Viral RNA in Host Cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2018, 189, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawatari, K.; Kadomura-Ishikawa, Y.; Emoto, T.; Onoda, Y.; Ishida, K.; Toda, S.; Uebanso, T.; Aizawa, T.; Yamauchi, S.; Fujikawa, Y.; et al. Viral Inactivation by Light-Emitting Diodes: Action Spectra Reveal Genomic Damage as the Primary Mechanism. Viruses 2025, 17, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, S.E.; Rodriguez, R.A.; Hawkins, M.A.; Hargy, T.M.; Larason, T.C.; Linden, K.G. Comparison of UV-Induced Inactivation and RNA Damage in MS2 Phage across the Germicidal UV Spectrum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 82, 1468–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araud, E.; Fuzawa, M.; Shisler, J.L.; Li, J.; Nguyen, T.H. UV Inactivation of Rotavirus and Tulane Virus Targets Different Components of the Virions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e02436-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, T.; Ebong, A.; Raja, M.Y. A Review of Light-Emitting Diodes and Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes and Their Applications. Photonics 2024, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K.; Onoda, Y.; Kadomura-Ishikawa, Y.; Nagahashi, M.; Yamashita, M.; Fukushima, S.; Aizawa, T.; Yamauchi, S.; Fujikawa, Y.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Development of a Standard Evaluation Method for Microbial UV Sensitivity Using Light-Emitting Diodes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyara, A.M.; Torvinen, E.; Veijalainen, A.-M.; Heinonen-Tanski, H. The Effect of Chlorine and Combined Chlorine/UV Treatment on Coliphages in Drinking Water Disinfection. J. Water Health 2016, 14, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Pitchers, R.; Hassard, F. Coliphages as Viral Indicators of Sanitary Significance for Drinking Water. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 941532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMinn, B.R.; Ashbolt, N.J.; Korajkic, A. Bacteriophages as Indicators of Faecal Pollution and Enteric Virus Removal. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 65, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüssow, H.; Hendrix, R.W. Phage Genomics: Small Is Beautiful. Cell 2002, 108, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clokie, M.R.; Millard, A.D.; Letarov, A.V.; Heaphy, S. Phages in Nature. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, S.E.; Wright, H.B.; Hargy, T.M.; Larason, T.C.; Linden, K.G. Action Spectra for Validation of Pathogen Disinfection in Medium-Pressure Ultraviolet (UV) Systems. Water Res. 2015, 70, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyersberg, L.; Klemens, E.; Buehler, J.; Vatter, P.; Hessling, M. UVC, UVB and UVA Susceptibility of Phi6 and Its Suitability as a SARS-CoV-2 Surrogate. AIMS Microbiol. 2022, 8, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyersberg, L.; Sommerfeld, F.; Vatter, P.; Hessling, M. UV Radiation Sensitivity of Bacteriophage PhiX174—A Potential Surrogate for SARS-CoV-2 in Terms of Radia-tion Inactivation. AIMS Microbiol. 2023, 9, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbonimpa, E.G.; Blatchley, E.R.; Applegate, B.; Harper, W.F. Ultraviolet A and B Wavelength-Dependent Inactivation of Viruses and Bacteria in the Water. J. Water Health 2018, 16, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattanakul, S.; Oguma, K. Inactivation Kinetics and Efficiencies of UV-LEDs against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Legionella Pneumophila, and Surrogate Microorganisms. Water Res. 2018, 130, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamane-Gravetz, H.; Linden, K.G.; Cabaj, A.; Sommer, R. Spectral Sensitivity of Bacillus Subtilis Spores and MS2 Coliphage for Validation Testing of Ultraviolet Reactors for Water Disinfection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 7845–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatchley, E.R.; Brenner, D.J.; Claus, H.; Cowan, T.E.; Linden, K.G.; Liu, Y.; Mao, T.; Park, S.-J.; Piper, P.J.; Simons, R.M.; et al. Far UV-C Radiation: An Emerging Tool for Pandemic Control. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heßling, M.; Hönes, K.; Vatter, P.; Lingenfelder, C. Ultraviolet Irradiation Doses for Coronavirus Inactivation—Review and Analysis of Coronavirus Photoinactivation Studies. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2020, 15, Doc08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonanno, M.; Welch, D.; Shuryak, I.; Brenner, D.J. Far-UVC Light (222 Nm) Efficiently and Safely Inactivates Airborne Human Coronaviruses. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-J.; Liao, C.-C.; Chang, C.-S.; Lee, C.-Y.; Chen, S.-Y.; Huang, S.-B.; Yeh, Y.-F.; Singh, K.J.; Kuo, H.-C.; Lin, Y.-L.; et al. The Effectiveness of Far-Ultraviolet (UVC) Light Prototype Devices with Different Wavelengths on Disinfecting SARS-CoV-2. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Linden, Y.S.; Gundy, P.M.; Gerba, C.P.; Sobsey, M.D.; Linden, K.G. Inactivation of Coronaviruses and Phage Phi6 from Irradiation across UVC Wavelengths. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoda, Y.; Nagahashi, M.; Yamashita, M.; Fukushima, S.; Aizawa, T.; Yamauchi, S.; Fujikawa, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Kadomura-Ishikawa, Y.; Ishida, K.; et al. Accumulated Melanin in Molds Provides Wavelength-Dependent UV Tolerance. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2024, 23, 1791–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K.; Matsubara, M.; Nagahashi, M.; Onoda, Y.; Aizawa, T.; Yamauchi, S.; Fujikawa, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Kadomura-Ishikawa, Y.; Uebanso, T.; et al. Efficacy of Ultraviolet-Light Emitting Diodes in Bacterial Inactivation and DNA Damage via Sensitivity Evaluation Using Multiple Wavelengths and Bacterial Strains. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguma, K. Inactivation of Feline Calicivirus Using Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365, fny194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowker, C.; Sain, A.; Shatalov, M.; Ducoste, J. Microbial UV Fluence-Response Assessment Using a Novel UV-LED Collimated Beam System. Water Res. 2011, 45, 2011–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sholtes, K.; Linden, K.G. Pulsed and Continuous Light UV LED: Microbial Inactivation, Electrical, and Time Efficiency. Water Res. 2019, 165, 114965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Taghipour, F.; Mohseni, M. Microorganisms Inactivation by Wavelength Combinations of Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes (UV-LEDs). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 665, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.; Gabbai, U.E.; Moram, M.A. Optical Fluence Modelling for Ultraviolet Light Emitting Diode-Based Water Treatment Systems. Water Res. 2014, 66, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Dunkin, N.; Schwab, K.J.; McQuarrie, J.; Bell, K.; Jacangelo, J.G. Infectivity Reduction Efficacy of UV Irradiation and Peracetic Acid-UV Combined Treatment on MS2 Bacterio-phage and Murine Norovirus in Secondary Wastewater Effluent. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 221, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyara, A.M.; Heinonen-Tanski, H.; Veijalainen, A.-M.; Torvinen, E. UV-LEDs Efficiently Inactivate DNA and RNA Coliphages. Water 2017, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, N.M.; Linden, K.G. Synergy of MS2 Disinfection by Sequential Exposure to Tailored UV Wavelengths. Water Res. 2018, 143, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.-J.; Kim, J.-W.; Choi, J.-B.; Chung, M.-S. Effects of the Specific Wavelength and Intensity of Intense Pulsed Light (IPL) on Microbial Inactivation. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, A.; Vink, A.A.; Gaspar, S.; Berces, A.; Modos, K.; Ronto, G.; Roza, L. Assessment of the Effects of Various UV Sources on Inactivation and Photoproduct Induction in Phage T7 Dosimeter. Photochem. Photobiol. 1998, 68, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockey, N.C.; Henderson, J.B.; Chin, K.; Raskin, L.; Wigginton, K.R. Predictive Modeling of Virus Inactivation by UV. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 3322–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc Canh, V.; Yasui, M.; Torii, S.; Oguma, K.; Katayama, H. Susceptibility of Enveloped and Non-Enveloped Viruses to Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diode (UV-LED) Irradiation and Implications for Virus Inactivation Mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2023, 9, 2283–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plano, L.M.D.; Franco, D.; Rizzo, M.G.; Zammuto, V.; Gugliandolo, C.; Silipigni, L.; Torrisi, L.; Guglielmino, S.P.P. Role of Phage Capsid in the Resistance to UV-C Radiations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, S.E.; Hull, N.M.; Poepping, C.; Linden, K.G. Wavelength-Dependent Damage to Adenoviral Proteins Across the Germicidal UV Spectrum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, S.E.; Rodriguez, R.A.; Linden, K.G.; Hargy, T.M.; Larason, T.C.; Wright, H.B. Wavelength Dependent UV Inactivation and DNA Damage of Adenovirus as Measured by Cell Culture Infectivity and Long Range Quantitative PCR. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devitt, G.; Johnson, P.B.; Hanrahan, N.; Lane, S.I.R.; Vidale, M.C.; Sheth, B.; Allen, J.D.; Humbert, M.V.; Spalluto, C.M.; Hervé, R.C.; et al. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Inactivation Using UVC Laser Radiation. ACS Photonics 2024, 11, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.; Mandal, I.; Singh, S.; Paul, A.; Mandal, B.; Venkatramani, R.; Swaminathan, R. Near UV-Visible Electronic Absorption Originating from Charged Amino Acids in a Monomeric Protein. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 5416–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, M.; Hartmann, C.; Guttmann, M.; Juda, U.; Muhin, A.; Höpfner, J.; Wernicke, T.; Straubinger, T.; Kneissl, M. Light Extraction and External Quantum Efficiency of 235 nm Far–Ultraviolet-C Light-Emitting Diodes on Single-Crystal AlN Substrates. Phys. Status Solidi A 2025, 222, 2400812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, K.; Mawatari, K.; Bui, T.K.N.; Kadomura-Ishikawa, Y.; Uebanso, T.; Hirakawa, H.; Awamoto, K.; Wakitani, M.; Shinoda, T.; Takahashi, A. Development of Mercury-Free Far-UVC Light Source Using Luminous Array Film Technology and Its Germicidal Effects. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 80612–80620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coliphage Strain | Pathogenic Virus [5] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSV | HMPV | |||

| r | p | r | p | |

| MS2 | 0.9888 | <0.001 | 0.9681 | <0.001 |

| Qb | 0.9978 | <0.001 | 0.9739 | <0.001 |

| PhiX174 | 0.9918 | <0.001 | 0.9705 | <0.001 |

| T1 | 0.9666 | <0.001 | 0.9454 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mawatari, K.; Onoda, Y.; Kadomura-Ishikawa, Y.; Emoto, T.; Yamaguchi, M.; Hirano, N.; Toda, S.; Matsubara, M.; Uebanso, T.; Aizawa, T.; et al. Evaluation and Comparison of the UV-LED Action Spectra for Photochemical Disinfection of Coliphages and Human Pathogenic Viruses. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122798

Mawatari K, Onoda Y, Kadomura-Ishikawa Y, Emoto T, Yamaguchi M, Hirano N, Toda S, Matsubara M, Uebanso T, Aizawa T, et al. Evaluation and Comparison of the UV-LED Action Spectra for Photochemical Disinfection of Coliphages and Human Pathogenic Viruses. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122798

Chicago/Turabian StyleMawatari, Kazuaki, Yushi Onoda, Yasuko Kadomura-Ishikawa, Takahiro Emoto, Momoka Yamaguchi, Nozomi Hirano, Sae Toda, Mina Matsubara, Takashi Uebanso, Toshihiko Aizawa, and et al. 2025. "Evaluation and Comparison of the UV-LED Action Spectra for Photochemical Disinfection of Coliphages and Human Pathogenic Viruses" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122798

APA StyleMawatari, K., Onoda, Y., Kadomura-Ishikawa, Y., Emoto, T., Yamaguchi, M., Hirano, N., Toda, S., Matsubara, M., Uebanso, T., Aizawa, T., Yamauchi, S., Fujikawa, Y., Tanaka, T., Li, X., Suarez-Lopez, E., Kuhn, R. J., Blatchley, E. R., III, & Takahashi, A. (2025). Evaluation and Comparison of the UV-LED Action Spectra for Photochemical Disinfection of Coliphages and Human Pathogenic Viruses. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122798