Depth-Related Patterns and Physicochemical Drivers of Soil Microbial Communities in the Alpine Desert of Ngari, Xizang

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Soil Sampling

2.2. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

2.3. Sequence Processing and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Characteristics of Soils at Different Depths in Beishan, Ngari

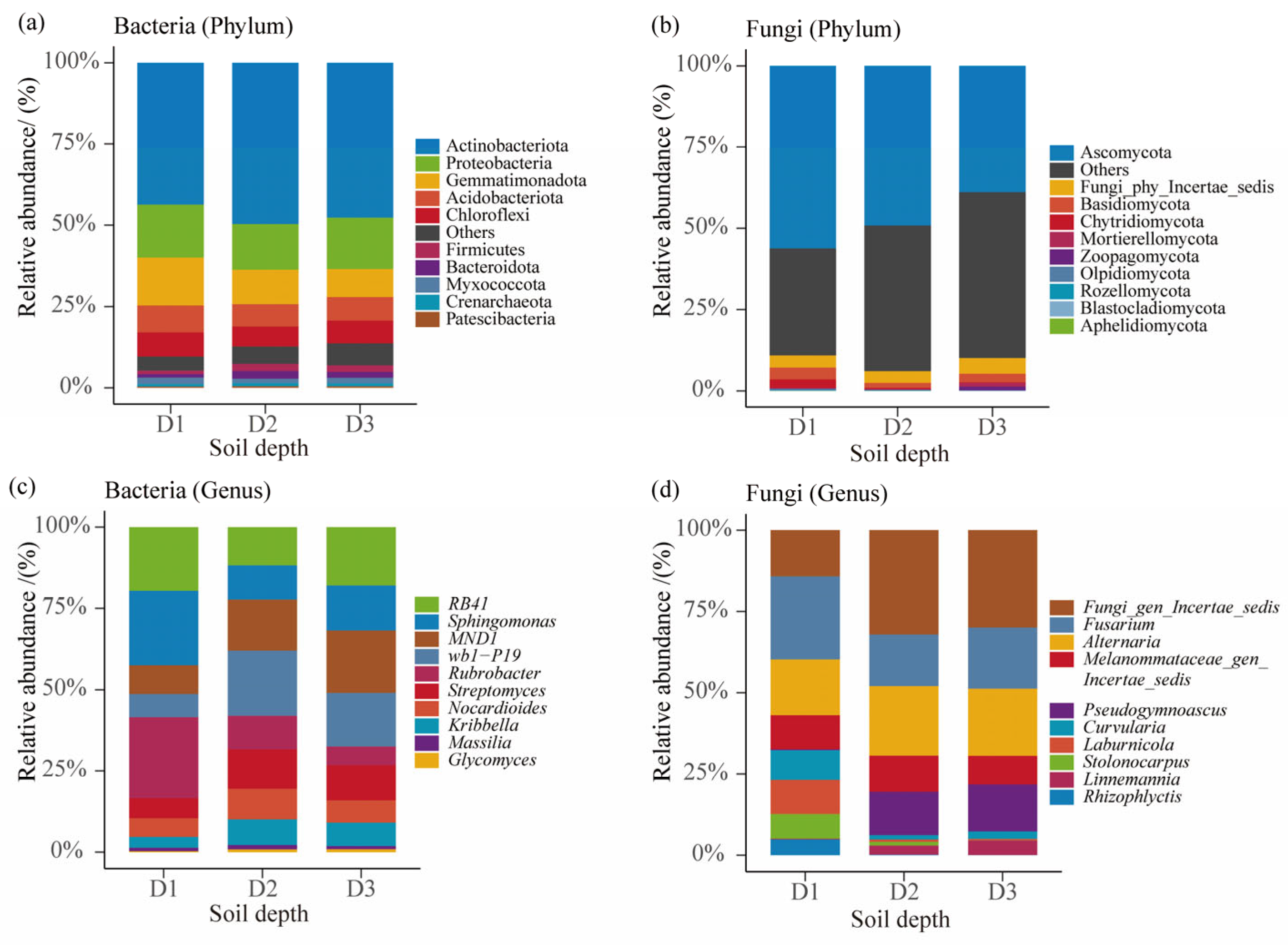

3.2. Composition and Abundance of Microbial Communities at Different Soil Depths in Beishan, Ngari

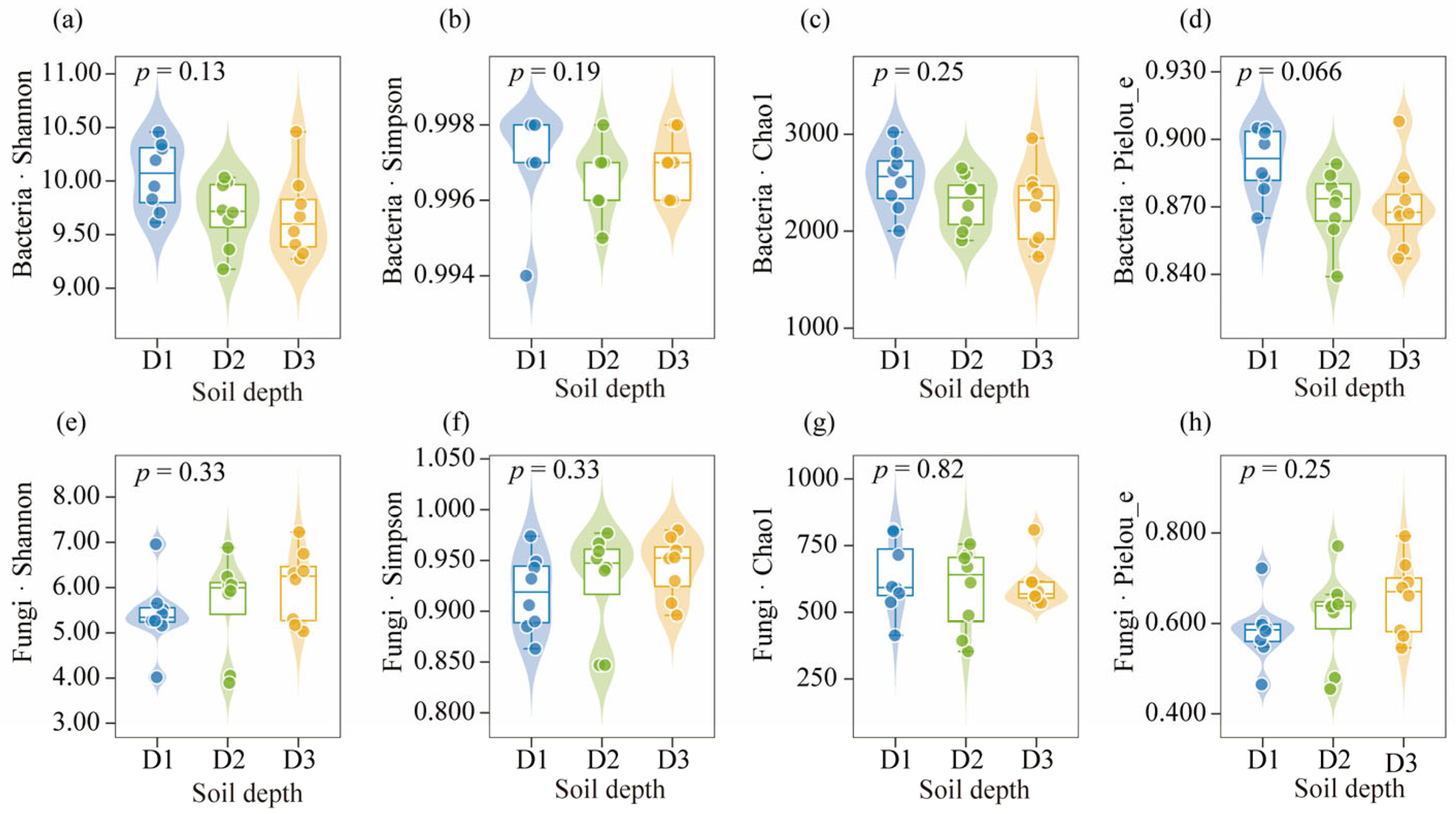

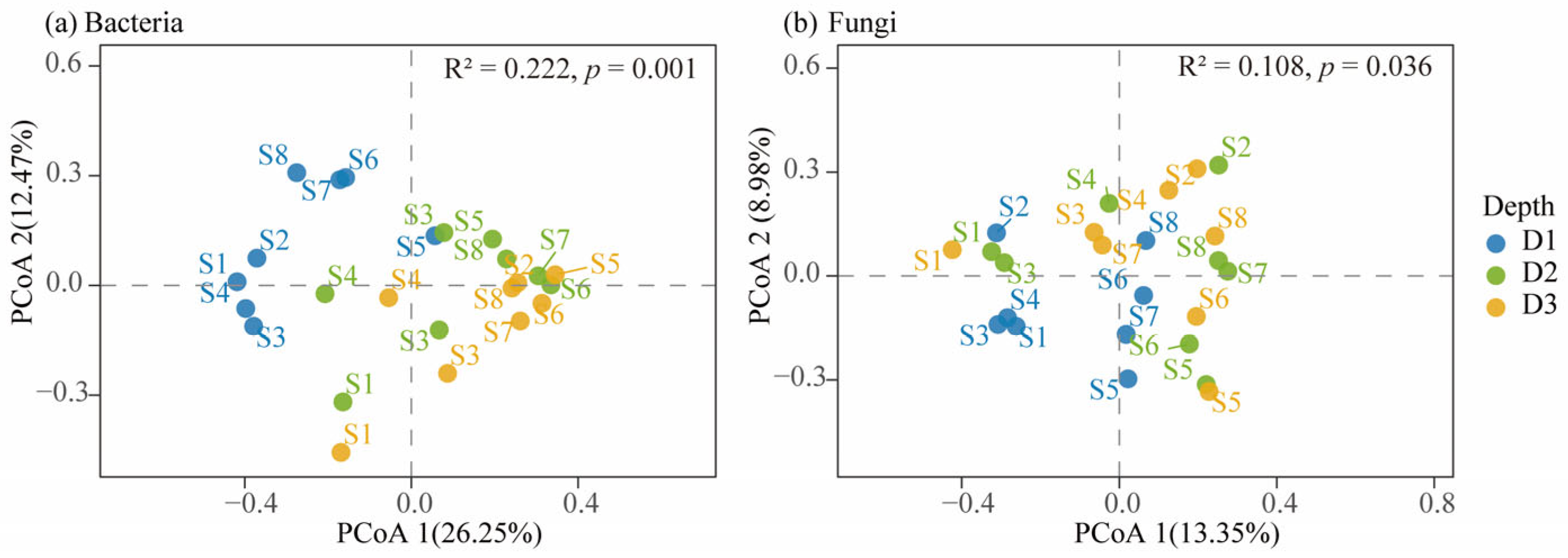

3.3. Microbial Community Diversity at Different Soil Depths in Beishan, Ngari

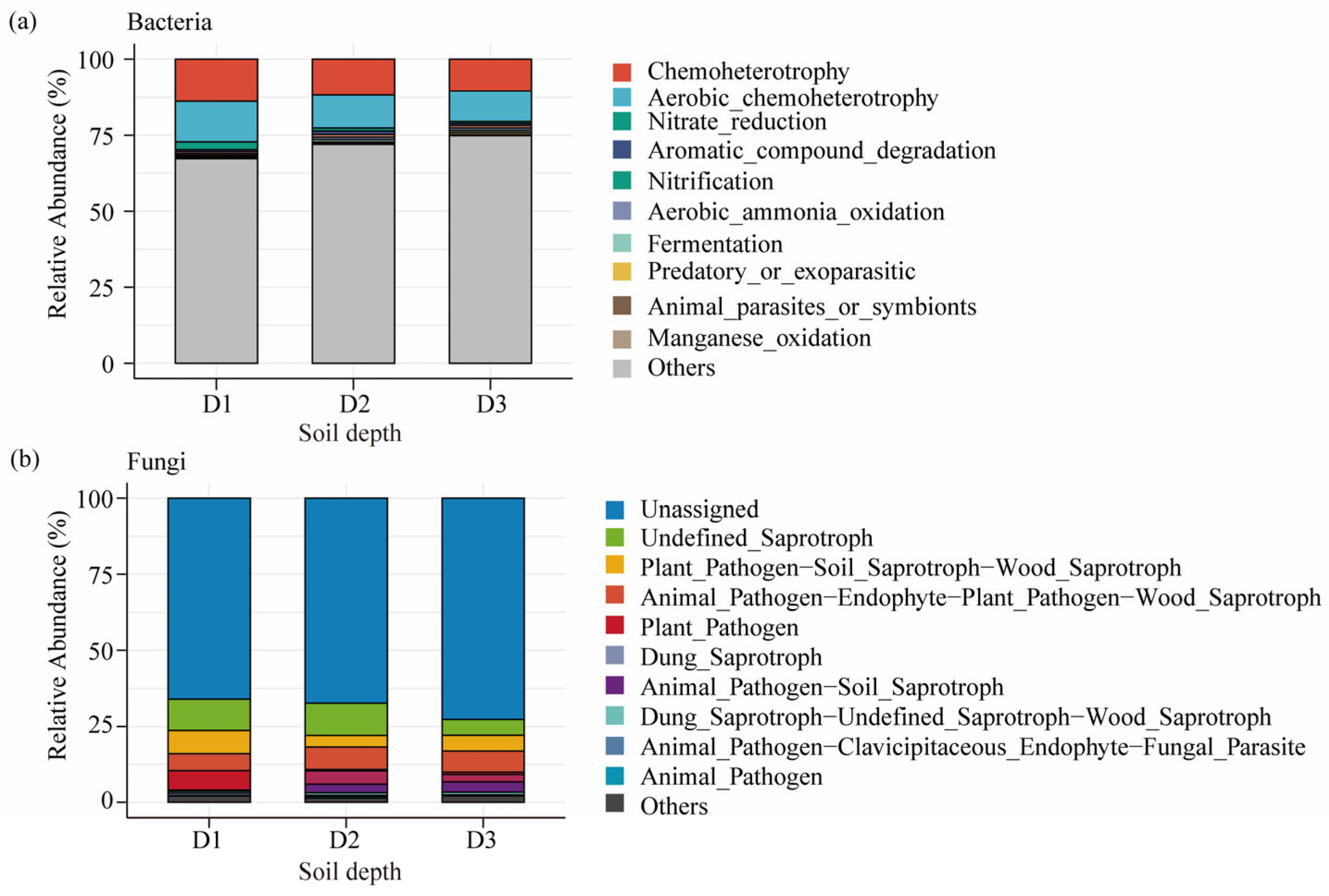

3.4. Functional Characteristics of Microbial Communities at Different Soil Depths in Beishan, Ngari

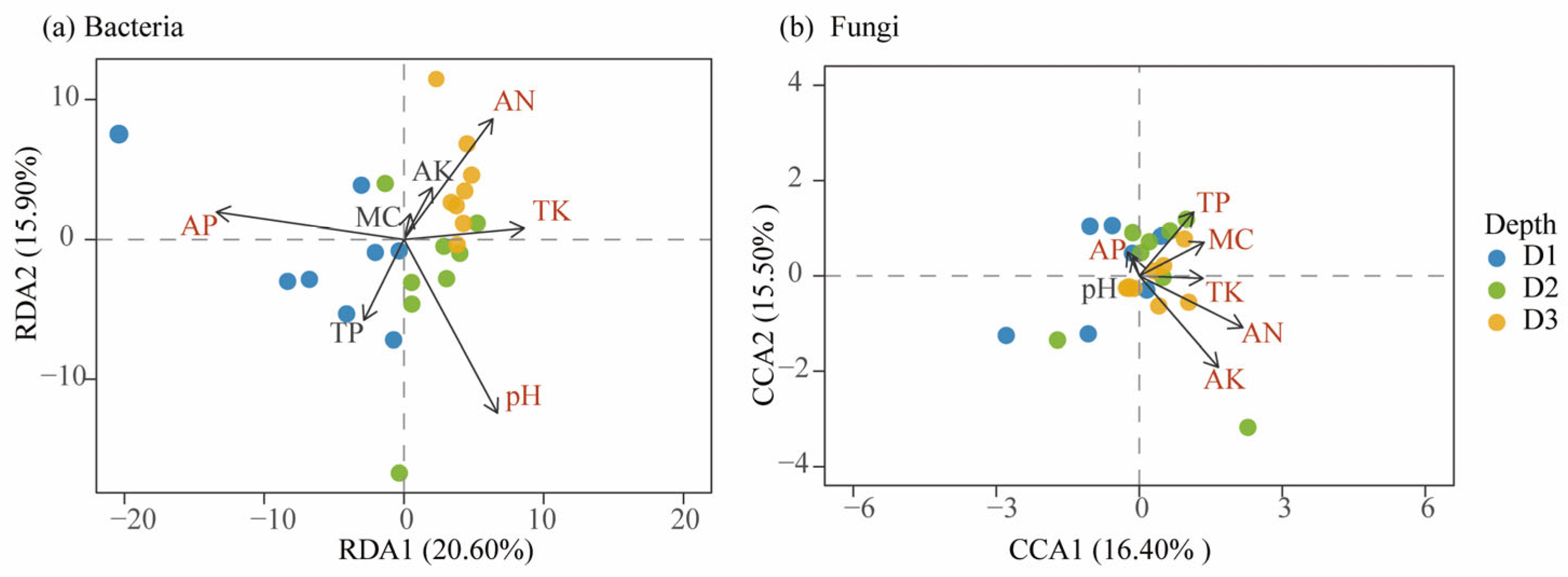

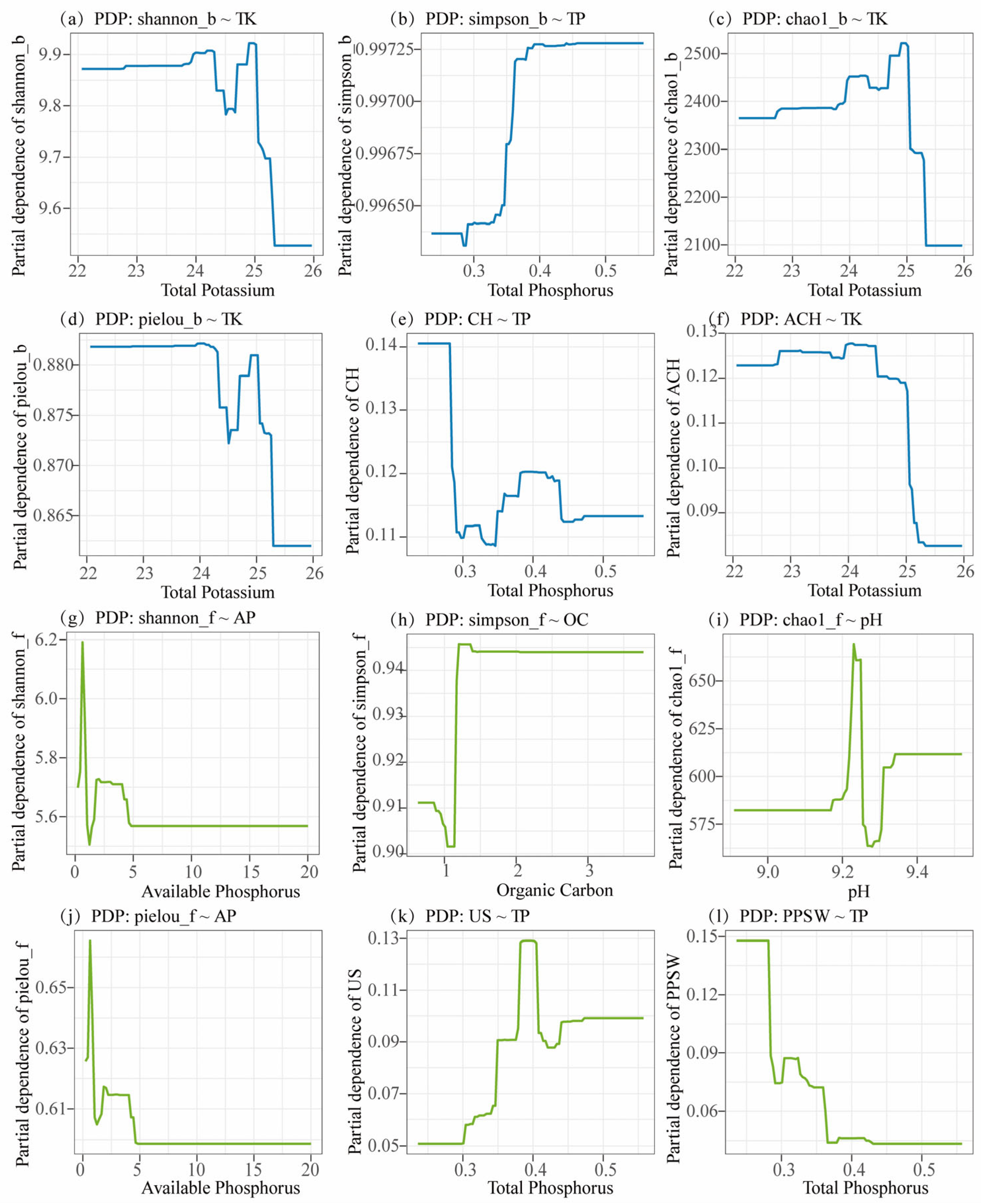

3.5. Relationship Between Microbial Communities and Environmental Factors Across Soil Depths in Beishan, Ngari

4. Discussion

4.1. Vertical Distribution Characteristics of Alpine Desert Soil Microbial Communities

4.2. Driving Mechanisms of Physicochemical Factors on Alpine Desert Soil Microbial Communities

4.3. Indicative Potential and Research Perspectives on Microbial Ecological Processes Under the Contexts of Alpine Desert Ecosystem Restoration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| D1 | 0–20 cm soil depth |

| D2 | 20–40 cm soil depth |

| D3 | 40–60 cm soil depth |

| RDA | Redundancy Analysis |

| CCA | Canonical Correspondence Analysis |

| DCA | Detrended Correspondence Analysis |

| BRT | Boosted Regression Tree |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| AN | Alkali-Hydrolyzable Nitrogen |

| TP | Total Phosphorus |

| AP | Available Phosphorus |

| TK | Total Potassium |

| AK | Available Potassium |

| OC | Organic Carbon |

| OM | Organic Matter |

| MC | Moisture Content |

| ASV | Amplicon Sequence Variant |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| PDP | Partial Dependence Plot |

| CH | Chemoheterotrophy |

| ACH | Aerobic Chemoheterotrophy |

| US | Undefined Saprotroph |

| PPSW | Plant Pathogen–Saprotroph–Wood Saprotroph |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Analytical Method | Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|

| pH | Potentiometric method (1:2.5 soil-to-water suspension, glass electrode, deionized water). | HJ 962-2018 [58] |

| TN | Kjeldahl nitrogen determination (semi-micro distillation titration). | HJ 717-2014 [59] |

| AN | Alkali diffusion–colorimetric method. | LY/T 1228-2015 [60] |

| TP | Mo-Sb Anti spectrophotometric method | HJ 632-2011 [61] |

| AP | 0.5 mol·L−1 NaHCO3 (pH 8.5) extraction–molybdenum–antimony colorimetric method (Olsen method). | NY/T 1121.7-2014 [62] |

| TK | HF–HClO4 digestion–flame photometry method. | NY/T 87-1988 [63] |

| AK | 1 mol·L−1 NH4OAc (pH 7.0) extraction–flame photometry method. | NY/T 889-2004 [64] |

| OC | Determined as the difference between total carbon (TC) and inorganic carbon (IC) using an elemental analyzer. | —— |

| OM | Calculated as OC × 1.724. | Soil Agricultural Chemical Analysis Methods [65] |

| MC | Oven-drying method at 105 °C to constant weight. | NY/T 52-1987 [66] |

References

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Durán, J.; Lu, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y. Environmental drivers of soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation in global drylands. Geoderma 2024, 451, 117075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Bao, A.; Jiapaer, G.; Guo, H.; Zheng, G.; Jiang, L.; Chang, C.; Tuerhanjiang, L. Disentangling the relative impacts of climate change and human activities on arid and semiarid grasslands in Central Asia during 1982–2015. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 1311–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Liu, X. Analysis of spatial-temporal patterns and driving mechanisms of land desertification in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Lian, Y.C.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhao, Y. R Review on the application of biological soil crusts in the prevention and control of aeolian desertification. J. Desert Res. 2025, 45, 31–38. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, W.; Zeng, F.; Siddiqui, J.A.; Zhihao, Z.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Alshaharni, M.O.; Khan, K.A. Combating desertification: Comprehensive strategies, challenges, and future directions for sustainable solutions. Biol. Rev. 2025, in press. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Van Der Putten, W.H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 2014, 515, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Huang, L.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Y.; Ning, Z.; Hu, R.; Zhang, Z. Microbial keystone taxa and nitrogen cycling enzymes driven by the initial quality of litter jointly promoted the litter decomposition rates in the Tengger Desert, Northern China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 207, 105919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Deng, L.; Wu, J.; Huang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Peñuelas, J.; Liao, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, H.; et al. Global change modulates microbial carbon use efficiency: Mechanisms and impacts on soil organic carbon dynamics. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, J.; Jiang, L.; Lv, G.; Hu, D.; Wu, D.; Yang, X. Rhizosphere effect and water constraint jointly determined the roles of microorganism in soil phosphorus cycling in arid desert regions. Catena 2023, 222, 106809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Liu, S.; Hu, M.Z.; Shi, X.R.; Dai, J.X. Screening of nitrogen-fixing microorganisms in the rhizosphere soil of desert plants and their stress-tolerance growth-promoting traits. Biotechnol. Bull. 2025, 41, 317–326. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, T.; Santos, J.; Matos, D.; Sá, C.; Pina, D.; Pinto, R.; Cardoso, P.; Figueira, E. Soil bacteria from the Namib Desert: Insights into plant growth promotion and Osmotolerance in a hyper-arid environment. Land 2024, 13, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Huang, Y.; Liu, B.; Chen, J.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, B.; Zhou, T.; Peng, S. Effects of daytime and nighttime warming on soil microbial diversity. Geoderma 2024, 447, 116909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Z.; Wang, X.R.; Du, M.; Ha, J.Q.; Wang, Q.; Shen, Y.F.; Yang, X.G. Analysis of soil microbial diversity in different habitats of arid and saline-alkaline regions in Qinghai. Northwest Agric. J. 2025, 34, 309–318. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.X. Soil Microbial Diversity and Environmental Responses in Arid Soils of Hexi Corridor. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, P.; An, S.Z.; Dong, Y.Q.; Sun, Z.J.; Berdawulet, X.H.; Li, C. A high-throughput sequencing evaluation of bacterial diversity and community structure of the desert soil in the Junggar Basin. Acta Pratacult. Sin. 2020, 29, 182–190. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X.; Yin, H.; Zhu, Z.; Qiu, Q.H.; Liu, Y.R.; Fan, J.K.; Deng, J.W.; Zhang, D.J.; Zhang, B.Y. Differences and influencing factors of bacterial composition and diversity in seven typical extreme habitats on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 2023, 63, 3235–3251. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yu, W.; Shi, Z. Estimating soil bacterial abundance and diversity in the Southeast Qinghai–Xizang Plateau. Geoderma 2022, 416, 115807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Hai, T.; Yuan, Z. Reflections on ecological restoration and protection in the middle reaches of the Shiquan River. Shaanxi Water Resour. 2020, 12, 147–148. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tian, R.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Y. Analysis of factors limiting the distribution of woody plants in high-altitude regions of the Tibetan Plateau under global warming. J. Hunan Ecol. Sci. 2021, 8, 15–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tao, D.L. A brief discussion on the greening of urban roads in Shiquanhe Town. For. Constr. 2010, 01, 51–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; He, L.; Zhu, R. Differentiated assistance and greater ecological construction: Planning exploration of Shiquanhe Town in the Ali Region of the Tibet Autonomous Region. Urban Plan. 2010, 34, 77–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, M.; Hepp, S.; Hardeep, F.N.U.; Nayak, A.; Liu, M.; Xing, X.; Zhang, H.; Liao, J. Differential roles of deterministic and stochastic processes in structuring soil bacterial ecotypes across terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleine, C.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; DiRuggiero, J.; Guirado, E.; Harfouche, A.L.; Perez-Fernandez, C.; Singh, B.K.; Selbmann, L.; Egidi, E. Dryland microbiomes reveal community adaptations to desertification and climate change. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, L.; Guo, Q.; Cao, S.; Zhan, Z. Diversity of bacterium communities in saline-alkali soil in arid regions of Northwest China. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, S.; Chu, H.; Zhang, B.; Wei, X.R.; Chen, W.M.; Wei, G.H. Linking soil fungi to bacterial community assembly in arid ecosystems. iMeta 2025, 4, e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, D.; McClure, R.; Jansson, J. Trends in microbial community composition and function by soil depth. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundra, S.; Kjønaas, O.J.; Morgado, L.N.; Krabberød, A.K.; Ransedokken, Y.; Kauserud, H. Soil depth matters: Shift in composition and inter-kingdom co-occurrence patterns of microorganisms in forest soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiab022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Chai, Y.-N.; Lopes, L.D.; Ordóñez, R.A.; Wright, E.E.; Archontoulis, S.; Schachtman, D.P. The effects of soil depth on the structure of microbial communities in agricultural soils in Iowa (United States). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e02673-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, M.; Wolf, A.B.; Jennings, S.J.; Kowalchuk, G.A. Micro-scale determinants of bacterial diversity in soil. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 936–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Crowther, T.W.; Isobe, K.; Wang, H.; Tateno, R.; Shi, W. Niche conservatism and community assembly reveal microbial community divergent succession between litter and topsoil. Mol. Ecol. 2025, 34, e17723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, R.; Su, M.; Song, H. Simulated wind erosion and local dust deposition affect soil micro-food web by changing resource availability. Ecol. Process. 2025, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.J.; Alicke, M.; Romdhane, S.; Pold, G.; Jones, C.M.; Saghaï, A.; Hallin, S. Resistance and resilience of co-occurring nitrifying microbial guilds to drying–rewetting stress in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 208, 109846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; Di Lonardo, D.P.; Bodelier, P.L.E. Revisiting life strategy concepts in environmental microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, F.T.; Griffiths, R.I.; Bailey, M.; Craig, H.; Girlanda, M.; Gweon, H.S.; Hallin, S.; Kaisermann, A.; Keith, A.M.; Kretzschmar, M.; et al. Soil bacterial networks are less stable under drought than fungal networks. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egidi, E.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Plett, J.M.; Wang, J.; Eldridge, D.J.; Bardgett, R.D.; Maestre, F.T.; Singh, B.K. A few Ascomycota taxa dominate soil fungal communities worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jia, L.-X.; Qiao, Q.-R.; Li, M.R.; Zhang, F.; Chen, D.L.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, M.L. Effects of heavy grazing on soil nutrient and microbial diversity in desert steppe. Chin. J. Grassl. 2019, 41, 72–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pointing, S.B.; Belnap, J. Microbial colonization and controls in dryland systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R.C.; Belnap, J.; Kuske, C.R. Soil bacterial and fungal community responses to nitrogen addition across soil depth and microhabitat in an arid shrubland. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Xu, M.; Li, Y.F.; Zhang, X.B. Elevational distribution pattern of fungal diversity and the driving mechanisms at different soil depths in Mount Segrila. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2023, 60, 1169–1182. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cong, M.; Zhang, Z.; Tariq, A.; Isiam, W.; Sardans, J.; Wang, W.; Gao, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhao, G.; Peñuelas, J.; et al. Vertical distribution of the soil microbiome in a desert ecosystem. Pedosphere 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Grishkan, I.; Kidron, G.J.; Rodriguez-Berbel, N.; Miralles, I.; Ortega, R. Altitudinal gradient and soil depth as sources of variations in fungal communities revealed by culture-dependent and culture-independent methods in the Negev Desert, Israel. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cao, Z.; Liu, S.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Sun, G.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, B. Soil fungal diversity, community structure, and network stability in the southwestern Tibetan Plateau. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mdaini, M.; Lloret, E.; Brahim, N.; Shimi, N.; Zornoza, R. Soil bacterial and fungal community composition in top- and subsoil from irrigated Mediterranean orchards. Span. J. Soil Sci. 2025, 15, 14537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, N.; Gherardi, L.A.; Sala, O.E.; Chung, Y.A. Dryland soil mycobiome response to long-term precipitation variability depends on host type. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 1802–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.Q.; Guigue, J.; Bauke, S.L.; Hempel, S.; Rillig, M.C. Soil depth and fertilizer shape fungal community composition in a long-term fertilizer agricultural field. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 207, 105943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhou, L.; Zou, B.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, Z.; He, J.-Z. Soil fungal diversity and functionality changes associated with multispecies restoration of Pinus massoniana plantation in subtropical China. Forests 2022, 13, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.B.; Menezes, A.D.; Finn, J.A.; Brennan, F.P. Plant species and soil depth differentially affect microbial diversity and function in grasslands. Soil Environ. Health 2024, 2, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Hou, W.; Liu, J.; Malik, K.; Kong, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Tang, M.; Zhu, R.; Cheng, C.; et al. Effects of different land use types and soil depths on soil mineral elements, soil enzyme activity, and fungal community in karst area of southwest China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Mitchell, J.; Scow, K. Cover cropping and no-till increase diversity and symbiotroph: Saprotroph ratios of soil fungal communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 129, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, J.W.; Califf, K.; Cardona, C.; Copeland, A.; van Treuren, W.; Josephson, K.L.; Knight, R.; Gilbert, J.A.; Quade, J.; Caporaso, J.G.; et al. Significant impacts of increasing aridity on the arid soil microbiome. mSystems 2017, 2, e00195-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, F.; Li, Y. Contrasting patterns and drivers of soil microbial communities in high-elevation montane grasslands and deserts of the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau, China. Catena 2025, 258, 109321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Xu, X. Competition between roots and microorganisms for nitrogen: Mechanisms and ecological relevance. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, L.D.; Pérez-Llano, Y.; Dickwella Widanage, M.C.; Jacob, A.; Martínez-Ávila, L.; Lipton, A.S.; Gunde-Cimerman, N.; Latgé, J.-P.; Batista-García, R.A.; Wang, T. Structural adaptation of fungal cell wall in hypersaline environment. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, A.T.; Yahdjian, L.; Stark, J.M.; Belnap, J.; Porporato, A.; Norton, U.; Ravetta, D.A.; Schaeffer, S.M. Water pulses and biogeochemical cycles in arid and semiarid ecosystems. Oecologia 2004, 141, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Maestre, F.T.; Gallardo, A.; Bowker, M.A.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Quero, J.L.; Ochoa, V.; Gozalo, B.; García-Gómez, M.; Soliveres, S.; et al. Decoupling of soil nutrient cycles as a function of aridity in global drylands. Nature 2013, 502, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuck, C.; Weig, A.; Spohn, M. Soil microbial biomass C:N:P stoichiometry and microbial use of organic phosphorus. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 85, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, P.; Hu, J.; Pan, Y.; Qu, X.; Ran, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, B. Response of soil fungal-community structure and function to land conversion to agriculture in desert grassland. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1413973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ 962-2018; Soil pH Analysis Quality Control Standard Material. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- HJ 717-2014; Soil Quality—Determination of Total Nitrogen—ModifiedKjeldahl Method. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- LY/T 1228-2015; Nitrogen Determination Methods of Forest Soils. The State Forestry Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- HJ 632-2011; Soil-Determination of Total Phosphorus by Alkali Fusion–Mo-Sb Anti Spectrophotometric Method. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- NY/T 1121.7-2014; Soil Testing—Part 7: Method for Determination of Available Phosphorus in Soil. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- NY/T 87-1988; Method for Determination of Total Potassium in Soils. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1988.

- NY/T 889-2004; Determination of Exchangeable Potassium and Non—Exchangeable Potassium Content in Soil. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2004.

- Lu, R. Soil Agricultural Chemical Analysis Methods; Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- NY/T 52-1987; Method for Determination of Moisture Content in Soils. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1987.

| Depth | pH | MC | TN | TP | TK | OC | OM | AN | AP | AK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 9.19 ± 0.12 a | 5.51 ± 0.7 a | 0.2 ± 0.12 a | 0.45 ± 0.07 a | 24.03 ± 1.24 a | 1.73 ± 0.87 a | 2.99 ± 1.5 a | 12.2 ± 3.75 a | 5.2 ± 6.41 a | 99.72 ± 50.76 a |

| D2 | 9.26 ± 0.09 a | 2.78 ± 0.8 b | 0.17 ± 0.08 a | 0.37 ± 0.07 ab | 24.12 ± 1.22 a | 1.45 ± 0.64 ab | 2.51 ± 1.11 ab | 11.81 ± 3.55 a | 2.28 ± 2.81 a | 59.69 ± 19.03 ab |

| D3 | 9.29 ± 0.10 a | 3.11 ± 0.7 b | 0.16 ± 0.1 a | 0.33 ± 0.06 b | 24.38 ± 0.95 a | 1.32 ± 0.96 b | 2.27 ± 1.65 b | 10.04 ± 5.67 a | 1.39 ± 1.48 a | 45.66 ± 18.76 b |

| Trait | pH | MC | TN | TP | TK | OC | OM | AN | AP | AK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shannon_b | −0.06 | −0.25 | −0.20 | 0.12 | −0.21 | −0.17 | −0.17 | −0.11 | 0.30 | 0.01 |

| Simpson_b | −0.20 | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.42 * | −0.31 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.34 | 0.16 |

| Chao1_b | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.09 | 0.23 | −0.34 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.34 | 0.08 |

| Pielou_b | −0.27 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.45 * | −0.30 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.29 |

| Shannon_f | −0.03 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.07 |

| Simpson_f | −0.20 | 0.35 * | 0.40 * | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.13 |

| Chao1_f | −0.18 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.02 * | 0.09 |

| Pielou_f | −0.29 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| CH | −0.13 | −0.25 | −0.17 | −0.12 | −0.37 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.12 | 0.22 | −0.17 |

| ACH | −0.07 | −0.30 | −0.24 | −0.10 | −0.43 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.17 | 0.20 | −0.20 |

| US | 0.05 | −0.11 | −0.06 | 0.42 | −0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.08 | −0.16 |

| PPSW | −0.02 | −0.29 | −0.03 | −0.25 | −0.25 | 0.10 | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.36 | −0.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Quzong, C.; Skal, S.-G.; Mu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Hei, E.; Yuan, X.; et al. Depth-Related Patterns and Physicochemical Drivers of Soil Microbial Communities in the Alpine Desert of Ngari, Xizang. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2775. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122775

Wang L, Quzong C, Skal S-G, Mu C, Zhao Y, Fang B, Zhang Y, Yang Z, Hei E, Yuan X, et al. Depth-Related Patterns and Physicochemical Drivers of Soil Microbial Communities in the Alpine Desert of Ngari, Xizang. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2775. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122775

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lan, Ciren Quzong, Sang-Gyal Skal, Chengwei Mu, Yaqin Zhao, Bo Fang, Yuan Zhang, Zhiyong Yang, Erping Hei, Xin Yuan, and et al. 2025. "Depth-Related Patterns and Physicochemical Drivers of Soil Microbial Communities in the Alpine Desert of Ngari, Xizang" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2775. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122775

APA StyleWang, L., Quzong, C., Skal, S.-G., Mu, C., Zhao, Y., Fang, B., Zhang, Y., Yang, Z., Hei, E., Yuan, X., & Dorji, T. (2025). Depth-Related Patterns and Physicochemical Drivers of Soil Microbial Communities in the Alpine Desert of Ngari, Xizang. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2775. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122775